Case Study #32

The Apple of My Eye:

A History of René Magritte’s, the Beatles’,

and Steve Jobs’ Entwined Trademarks

Paul McCartney rst saw the apple on his

dining room table in the summer of 1967.

Large, vivid green, with “Au Revoir” written

across it, McCartney immediately considered

the image of the fruit, painted by the Belgian

graphic designer, René Magritte, a year

earlier, to be iconic. As McCartney recalled,

“This big green apple, which I still have now,

became the inspiration for the logo” of the

Beatles’ multimedia company, Apple Corps,

that the band founded in 1968. McCartney and

his three bandmates—John Lennon, George

Harrison, and Ringo Starr—used Magritte’s

apple image, a recurring theme in the artist’s

work, as the starting point for their new

company’s logo. Imitating Magritte’s style

which presented familiar objects in strange

and unexpected ways, they printed their small, green Granny Smith apple on records, CDs, and other

merchandise.

1

Remarkably, the marketing potential of Magritte’s apple image did not end there.

Steve Jobs grew up listening to the Beatles. When the tech entrepreneur wanted to start his own company

with the engineer, Steve Wozniak, he called it “Apple” in tribute to the band. The pair launched Apple

Computer, with the logo of a small, rainbow coloured apple with a bite taken out of it, in 1976.

2

But the

Beatles did not want to share the apple branding and sued Apple Computer three times for trademark

infringement. Over the course of the next three decades, the two companies fought for the right to use their

version of the “Apple” name and logo. The recycled apple image that brought together a graphic designer,

pop band, and computer company sat at the heart of an intellectual property battle dening computer and

music innovation in the late twentieth and early twenty-rst century.

Ceci n’est pas une pomme

René Magritte did not live a typical bohemian artist’s life. Born in Lessines, Belgium, in 1898, he and

his childhood sweetheart and later wife, Georgette Berger, lived in the suburbs of Brussels. Magritte

spent his early career designing wallpaper and creating posters for the Brussels couture house, Norine.

He began adopting a more gurative style of painting in the mid-1920s and in 1927, René and Georgette

moved to Paris to explore the ourishing Surrealist movement. In France the couple encountered artists

experimenting with new creative styles that centred the imagination of dreams and the subconscious

Case study prepared by Dr Emma Day. Case study editor: Professor Christopher McKenna,

University of Oxford.

Support for this case study was provided by Novak Druce Carroll; a law rm specializing in

intellectual property and entrepreneurial inspiration.

1

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

February 2023

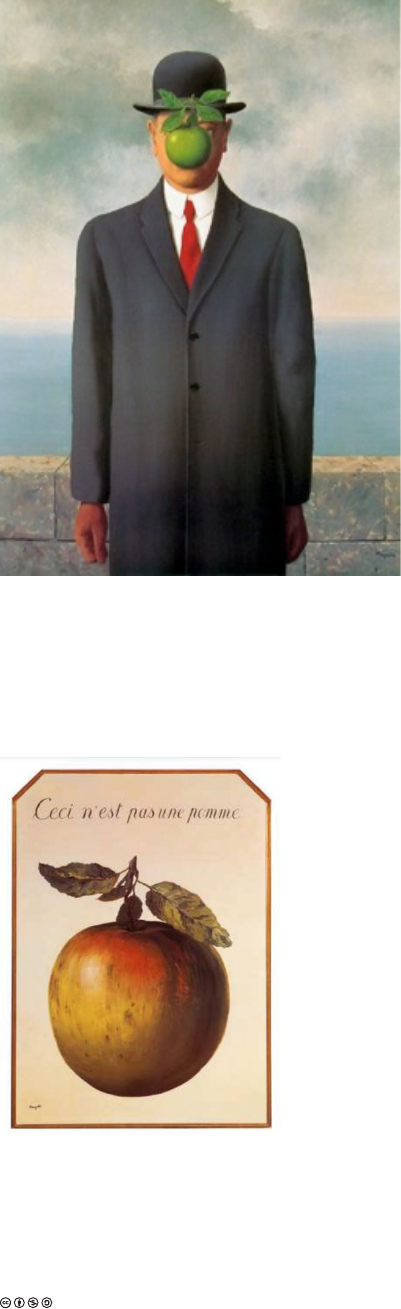

Rene Magritte, “Au Revoir,” 1966

mind to challenge bourgeois values, but they decided that the quiet suburbs suited them better. They

returned to Brussels and Magritte resumed his work in advertising. In his spare time, he took to his dining

room to paint. Craving routine, he painted at the same time every day dressed in a suit, tie, and slippers.

The surrealist art Magritte created appeared to contradict his conventional lifestyle. The gap between

Magritte’s art and his appearance surprised people, with some even labelling him an imposter and a con

man.

3

While his signature bowler hat and dark suit coded him as bourgeois and respectable, his work–

which drew inspiration from numerous sources, including earlier art movements such as impressionism,

cubism, and futurism, as well as lm, photography, Georgette, and what he described as “the banal” in

everyday life–nonetheless conrmed his place among the Belgium avant-garde.

4

Magritte not only took inspiration from everything around

him; he also inspired others. Probing the relationship

between what people perceive and what is real, Magritte’s

work informed Dadaism, an art movement that critiqued

the First World War through the repetition of satirical and

nonsensical images, as well as its successor, Surrealism.

Magritte’s questioning of art’s ability to represent reality also

inspired the pop artists of the mid-century from Britain and

the United States who, like surrealists and dadaists, wanted

to challenge traditional approaches to art which they believed

reected little of their daily lives. Instead, pop artists drew

inspiration from, incorporated, and critiqued everyday items

and sources of “low-brow” culture including Hollywood

movies, adverts, and cartoons. They also used commercial

advertising methods like silk screening to challenge the notion

that art is bespoke and original.

5

Drawing a direct lineage

between their subversion of common images and Magritte’s,

pop artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg

heralded the Belgian painter as the “father” of popular

culture.

6

The nineteenth century writer Isidore Lucien

Ducasse considered such borrowing of ideas a natural part

of the artistic process, writing that “plagiarism is necessary.

Progress implies it.”’

7

The scholar George Basalla concurred

that “Continuity prevails throughout the made world.”

8

While

artists commonly draw inspiration from the work of others,

Magritte nevertheless disliked this association, viewing pop art as “mere window dressing, advertising art” that

lacked originality or imagination: “pop art is nothing but a [sugar-coated] version of…good old Dadaism.”

9

Despite Magritte’s reservations, the Pop art movement nevertheless claimed him as their own.

Although Magritte rejected Pop art’s appropriation of his ideas, the rise

of the new movement which also elevated the everyday helped raise his

prole. While Magritte painted many of his most iconic works around his

stay in Paris in the late 1920s and 1930s, he only began enjoying international,

critical acclaim with the rise of Pop art in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1965,

Magritte travelled to the US for the rst time to attend the opening of a major

retrospective on his work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Favourable reviews highlighted Magritte’s relevance for Pop art.

10

Magritte

also became fashionable in wider popular culture circles. In what began the

Beatle’s life-long obsession with the Belgian artist, Paul McCartney bought

his rst Magritte painting in Paris a year after MoMa’s retrospective from

the inuential art dealer, Alexander Iolas.

11

Much to McCartney’s delight, in

the summer of 1967 (the same year that Magritte died), McCarney’s friend

and London gallery owner, Robert Fraser, brought him a Magritte painting

(“Au Revoir,” 1966) that, like many others, featured an unusual depiction of

an apple.

12

A similar green apple, which had obscured Magritte’s face in his

self-portrait, The Son of Man (1946), had “Goodbye” (“Au Revoir”) scrawled

across the image, perhaps anticipating his death a year later. Yet, in the hands of the global pop star, Magritte’s

apple, which wasn’t really an apple (like his famous painting of non-existent pipe, “The Treachery of Images,”

1929), took on a new meaning and a valuable trademark value.

2

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Rene Magritte, “The Son of Man”,

self-portrait, 1946

Rene Magritte, “Ceci n’est

pas une pomme,” 1964

The making of Apple Corps

The same year that McCartney acquired Magritte’s

“Au Revoir” painting, the Beatles began to head in new

creative and business directions. Exploding onto the

British music scene in the early 1960s with hits like

“Love Me Do (1962) and “She Loves You (1963)”, the

four Liverpudlian men became incredibly wealthy very

quickly. In 1967, their accountants advised them to invest

their growing capital in a business to pay less tax, and

the bandmates formed a company which they collectively

owned, called Beatles and Co. Ltd., that April. With the

founding of Beatles and Co. Ltd., the band entered a legal

partnership in which they agreed to share their income

from any group, live, or solo work in a deal that legally

bound them together for a decade.

13

The following month,

they released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,

an experimental album with bold aesthetics and songs

that provided that soundtrack to the “summer of love”

and which, at twenty-ve thousand pounds, cost more

than any previous album to produce. With a little green

apple image printed on the record sleeve, it also hinted

at the band’s new business ventures. In November, the

Beatles agreed on McCartney’s idea to rename Beatles

Ltd. to Apple Music Ltd in homage to Magritte. The

band’s manager, Brian Epstein, who also ran an artist

management company, New End Music Store (NEMS),

their accountant, Alistair Taylor, and solicitor, Neil

Aspinall became the company’s directors.

14

Tragedy

struck in August when Epstein, whom the band heavily

relied on to manage the entirety of their business dealings,

died of an accidental overdose.

15

The Beatles saw Epstein’s death as an opportunity to bring their music, prots, and nances more closely

under their own control. First, they had to agree on the nature of their new business.

16

Rejecting the

company directors’ original idea to sell greetings cards, the band opened a hip new boutique clothing

store in Marylebone in December 1967. In January 1968, the band decided to expand their business

horizons and Apple Music Ltd. became Apple Corps Ltd.–the “core” of their various business operations.

The multimedia company controlled a series of other business enterprises including lm, publishing,

merchandise, and other creative pursuits. This included a record label, Apple Records, on which the

Beatles released new albums, re-released old songs, and signed artists like James Taylor and Jackie

Lomax.

17

Unlike Lennon who likened himself to Magritte for living in the suburbs, McCartney, who

owned a at in the heart of London and embraced the capital’s experimental cultural scene, saw Apple

Corps as an opportunity to discover new talent.

18

The Beatles’ new company also needed a logo. Taking inspiration

from Magritte’s apple images, the Beatles hired graphic designer Gene

Mahon to design it. Mahon wanted to use a photograph of an apple on

the A-side of the label’s records, and an image of an apple cut in half on

the B-side which would also contain the track’s name, the running time,

artist, publishing, and copyright information. Mahon commissioned

photographer, Paul Castell, to photograph a series of apples set against

different coloured backgrounds. Six months later, the band settled on a

picture of a vibrant, shiny green Granny Smith. With the logo nished,

Aspinall, now the company’s managing director, wasted no time

registering the Apple Corps trademark in a total of forty-seven countries.

19

In August 1968, the band released “Hey Jude,” the rst on their new

record label and the single was an instant hit. Apple records released three

more popular albums in quick succession: Yellow Submarine in January

1969, Abbey Road in September 1969, and Let it Be in May 1970.

3

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Paul McCartney at home with Magritte’s

“A u R e v o i r,” undated

The Beatles, “Hey Jude,” 45

Single, 1968

Despite the success of their new music, fractures emerged among the four bandmates. They lacked

business savvy and, often high on psychedelic drugs, failed to properly manage the nances of Apple

Corps which quickly began losing large sums of money. The appointment of Allen Klein, an American

business manager, to oversee their nances in 1969, exacerbated growing tensions. While Lennon, Starr,

and Harrison believed in Klein’s ability to put their nancial affairs in order, McCartney distrusted him, and

instead wanted to hire his wife, Linda’s, brother, as their manager. Tensions came to a head in the Spring

of 1970, when McCartney announced publicly that the Beatles no longer existed. To prevent his bandmates

signing everything over to Klein, McCartney moved to legally dissolve the Beatles. On December 31, 1970,

he sued the Beatles in London’s High Court of Justice. The judge ruled in favour of dissolution, ending the

band’s contractual partnership. While the Beatles split, Apple Corps remained intact, and the owners doubled

down on their commitment to maintaining the Apple branding in the next decade.

20

Apple v Apple

Flicking through an in-ight magazine in 1978, an advertisement for a new computer company caught

George Harrison’s attention. Founded two years earlier by the tech entrepreneurs Steve Jobs and Steve

Wozniak, their new company logo, a large, rainbow coloured apple with a bite taken out of it, and name,

Apple Computer, seemed very similar to the Beatle’s company’s own brand and logo. Although Harrison

didn’t know it, the designer, Rob Janoff, had devised Apple’s new logo to emphasize the innovative color

display on the new Apple II computer with the leaf, in green, at the top at Steve Jobs’ request.

Born in February 1955 and raised in Mountain View, Santa Clara County, just south of Palo Alto, Jobs’

father’s passion for mechanics instilled in him an understanding of electronics and an appreciation for

good design. As a central hub of military research and development, the valley’s growing technology

industry meant that the Jobs’ family’s neighbourhood teemed with young engineers. As the Cold War

heated up, the opening of the NASA Ames Research Center and other government and privately funded

defence contractors transformed Silicon Valley into the technological capital of the world. In 1967, Paul

Jobs and his wife, Clara, spent all their savings to move to the more afuent Cupertino neighbourhood

and enrol their son in the academically rigorous Homestead High School, where Steve became involved

in the burgeoning counterculture movement alongside his studies. He grew his hair long, took LSD,

and listened to the Beatles, immersing himself in Cupertino’s dual worlds of arts and technology. He

dated artist Chrisenn Brennan and during the summer of 1968 got a job at the multinational information

technology company, Hewlett-Packard (HP), and early spinout from Stanford University. There, in 1971,

aged seventeen, Jobs met fellow Homestead alumni and HP employee Steve Wozniak, aged twenty,

who designed calculators for Hewlett Packard. The intertwining of the counter-culture and electrical

engineering cultures coalesced in the making of Apple Computer.

21

Steve Wozniak loved experimenting with technology. In

1970, “Woz” built his rst tiny computer: “The Cream Soda.”

Later that year, Ron Rosenbaum’s article on “Secrets of the

Little Blue Box” in Esquire magazine’s Autumn edition gave

Wozniak an idea for a new project. Rosenbaum relayed stories

of so-called phone “phreaks” who created devices called

blue boxes that imitated the noise of someone dropping coins

into a phone machine, allowing the user to hack the phone

network and make free calls anywhere in the world. Wozniak

immediately shared the story with his friend, Jobs, and the

two excitedly rushed to the Stanford Linear Accelerator

Center library to hunt for a phone manual that listed the tone

frequencies they needed to mimic the noise and to build their

own box. After nding the phone company specications,

they hurried to a store to buy an analog tone generator kit.

After a long night spent constructing the analog blue box,

unfortunately, Wozniak couldn’t make it work work. Blaming

the imprecision of analog circuits, and uspecting that digital

circuits might work better, Wozniak set about building a

digital blue box made up of the chips that he already used in

making computers. Wozniak was right, and the digital blue

box proved much more successful in imitating the precise

tones used by AT&T, the American phone company. Steve

4

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Original Apple Computer logo, 1976

5

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Jobs demonstrated early signs of his ability to adapt existing ideas for prot when he suggested that the

pair sell their digital blue boxes to Berkeley college students for $170 a piece. The pair invested the $6,000

they raised into their new computer company founded in Cupertino, California.

22

After their initial success, Wozniak and Jobs began selling their rst

personal computer four years later. Having spent years experimenting

with new ways to build computer systems, Wozniak shared with Jobs

the basic design for the rst Apple Computer in 1976. After Wozniak

failed to sell the computer model to HP, Jobs suggested that they set

up their own company. On April 1, 1976, the pair launched the Apple

Computer Company which they ran from Jobs’ parents’ garage. One

year later, they settled on the company logo: a rainbow lled apple

with a bite taken out of it.

23

If Jobs chose the Apple name and logo to pay homage to the Beatles,

the band did not appreciate the gesture. Enforcing their trademark

rights, the Beatles sued Apple Computer for trademark violation in

1978. Having disbanded nearly a decade earlier, Apple Corps relied

on re-releasing old Beatles songs to stay in business, and worried that

the similarity of Apple Computer’s logo might confuse customers. The

two companies settled the case out of court in 1981. Apple Computer

pledged to pay Apple Corps $80,000 for the right to keep the Apple

name, and both companies decided to keep their name and respective

logos if Apple Corps agreed to never enter the world of computers and

Apple Computers agreed to never enter the world of music, and if both

agreed only to use their versions of Magritte’s apple image.

24

The settlement nevertheless failed to anticipate the imminent collision of the previously disparate worlds

of music and computers. Within a decade, Apple Computer launched three new computer systems:

the Apple Lisa in 1983 –the rst personal computer to include a graphical user interface adapted

from prototypes at Xerox PARC in Palo Alto— followed by the Macintosh computer in 1984, and the

Macintosh II in 1990. Indeed, the Macintosh Computer (so named in a nod to its Apple roots), with

a built-in Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI), could play music and interact with musical

instruments. In 1988, Apple Computer sued several competitors for copyright infringement, including

IBM, Microsoft, and Wozniak and Jobs’ former employer, HP, for selling computer systems that used

a similar graphical interface that Jobs had rst seen at Xerox. Apple Compter would win the case with

Microsoft paying a one-time fee and agreeing to make some changes to the Windows interface. But

a year later, in 1989, Steve Jobs found himself at the receiving end of litigation when a the Beatles’

lawyers led a second lawsuit claiming that tMacintosh computer’s capacity to play music violated the

previously agreed terms of the 1981 settlement.

In 1991, Apple Corps and Apple Computer reached a second out-of-court

settlement which further claried Apple Computer’s trademark rights

to the term “Apple.” The judge ruled that Apple Computer could use the

Apple name and logo on products with the capacity to “reproduce, run,

play, or otherwise deliver” music, but not on “physical media delivering

pre-recorded music,” such as CDs and cassettes. Apple Computer also

agreed to rename sound effects that referred to musical instruments

on their Macintosh computers. Honouring this promise, their sound

designer, Jim Reekes, renamed the beep sound “chimes” as “Sosumi,”

pronounced, “so sue me,” to mock the Beatles’ demands. The tech giant

also agreed to pay the British band a further $26.5 million in damages.

25

As Apple Computer’s technology became increasingly sophisticated,

Jobs did not let his agreement with Apple Corps stop him from venturing

further into the world of digital music. In October 2001, Apple Computer

released the iPod, a portable digital music player, and two years later,

Steve Jobs launched the iTunes digital Music Store, a service allowing

customers to purchase songs to download onto their iPods. Apple signed

Redesigned Apple Logo for

Apple II computer, 1977

First Apple iPod, 2001

6

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

deals with record companies to sell their music online through iTunes, which became the world’s largest

music retailer in less than two years. Unlike rival digital music platforms, iTunes allowed users to play

songs purchased through iTunes on different devices or burn them onto other media after they removed

their FairPlay Digital Rights Management (DRM) copy protection in 2009.

At the same time, the Beatles suffered several personal losses. Two of their band members, John Lennon,

and George Harrison, died, respectively, in 1980 and 2001, leaving Apple Corps under the management

of their widows, Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison, as well as the remaining band members, Ringo Starr and

Paul McCartney. The four chose not to licence the Beatles’ vast music catalogue for digital sales through

iTunes or any other digital platform—one of the few bands not to do so—fearing that people might

illegally copy and share songs released digitally. They also took issue with the iTunes branding. Although

Apple Computer did not use the name “Apple” in connection with the sale of music on the iTunes store,

the apple logo featured prominently. Not surprisingly, the executives at Apple Corps considered Apple

Computer’s use of the apple logo in connection to the sale of music yet another violation of the 1991

settlement agreement and, in 2003, for the third and nal time, Apple Corps sued Apple Computer to stop

Steve Jobs from using the apple image on the iTunes music store.

Unlike the rst two legal cases, the two companies did not settle their nal dispute out of court. Instead,

the UK High Court of Justice provided the backdrop to the concluding legal battle that began on March 29,

2006. Neither Jobs nor any Beatles members or widows attended the trial, leaving their companies’ fates

in the hands of their corporate lawyers. Geoffrey Vos, representing Apple Corps, argued that, through

iTunes, Apple Computer had unlawfully entered the music selling business. He decked out the High Court

with laptops and large video screens to demonstrate how the service worked for Justice Edward Mann,

downloading a copy of the disco band Chic’s Le Freak hit on a Dell laptop and playing it for the court.

Vos also played an iTunes television advertisement promoting the British band, Coldplay, who performed

their song, “speed of sound,” alongside the apple logo and a reference to iTunes.com. According to Vos,

this promotion proved Apple Computer’s unlawful use of the apple logo in connection with the sale of

music. Vos also argued that Steve Jobs had offered $1 million to buy the rights to the Apple Record name

from the Beatles in 2003. Anthony Grabiner, representing Apple Computer, offered a simpler defence: the

iTunes store merely acted as a conduit for the transmission, and not the sale, of digital music. Determining

that digital music was not the same as physical media, Mann ruled in favour of Apple Computer in May.

26

In the third and nal confrontation over René Magritte’s artistic invention, Steve Jobs held onto the

forbidden fruit.

Conclusion

In January 2007, Steve Jobs stood on the stage of the Moscone

Convention Center, in San Francisco, before a crowd of 7,500

people eagerly awaiting his announcement of Apple Computer’s

latest multimedia product, the iPhone. Combining the iPod, a

phone, and an internet communicator, Jobs shared Apple’s mission

to “reinvent the phone.” While demonstrating the phone’s iPod

feature, Jobs clicked on the iPod icon, scrolled down, and selected

the Beatles. Landing on their 1967 album, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely

Hearts Club Band, Jobs chose the song, “With A Little Help from

My Friends,” and the sound and image of the four Beatles lled the

auditorium.

27

The company sold 270,000 iPhones during the rst

thirty hours it was available for sale. During his announcement

of the iPhone, Jobs also explained that Apple Computer would be

renamed Apple Inc., reecting the widening scope of company in

personal devices.

One month later, news outlets reported on the agreement reached

between the two Apple companies on the Apple trademark. Under

the terms of the nal settlement agreement, Apple Inc. now owned

all the trademarks related to “Apple,” allowing the Cupertino

juggernaut to keep using its corporate name and logo on iTunes.

Apple Inc. also agreed to licence certain trademarks back to Apple Corps. Jobs expressed relief at nally

reaching a resolution with a band he “loved.”

28

Following the third and nal confrontation over René

Magritte’s artistic invention, Steve Jobs nally held all the rights to the forbidden fruit.

Steve Jobs unveils the iPhone,

January 2007

7

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Coincidentally Apple Inc. settled another intellectual property lawsuit in February 2007. Six weeks

earlier, the San Jose digital communications technology corporation, Cisco Systems, had sued Apple Inc.

for trademark infringement. Lawyers at Cisco had previously trademarked the name “iPhone” in 2000

for their telephone devices which connected to the internet and argued that Apple’s use of it violated

Cisco’s intellectual property. Steve Jobs had chosen to announce Apple’s iPhone before settling the case.

Eventually, the two companies reached a deal to both continue using the iPhone name regardless, implying

a disregard for Cisco’s grievance.

29

Steve Jobs’ use of the Beatles in his presentation introducing the iPhone raised many their fan’s hopes that

the Beatles’ music might nally become available via digital download on iTunes. Unfortunately, another

three more years passed before iTunes became the only place to buy Beatles songs digitally. In 2010, the

two Apple’s images nally appeared alongside each another for the rst time to promote both companies’

products. When Steve Jobs died one year later, Tim Cook took over as CEO of Apple and, in January

2022, 10 years after Steve Jobs death, 52 years after the Beatles disbanded, and 55 years after René

Magritte died, Apple became the most valuable company in the world with an estimated “brand value” of

nearly one trillion dollars. A remarkable development for a common fruit whose Latin name, “malus,”

also translates as “evil.” René, no doubt, would have been très amusé.

The Beatles on iTunes, 2010

8

Endnotes

1

Sam Kemp, “Paul McCartney’s deep adoration for the surrealist artist René Magritte,” November 17,

2021, https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/paul-mccartney-adoration-surrealist-artist-rene-magritte/.

2

Craig Silver, “How a Magritte Painting Led to Apple Computer,” Forbes, December 5, 2013,

https://www.forbes.com/sites/craigsilver/2013/12/05/how-a-magritte-painting-lead-to-apple-

computer/?sh=3996ecd8228f.

3

Sandra Zalman, Consuming Surrealism in American Culture, 94.

4

Alex Danchev, Magritte: A Life (London: Prole Books, 2021), no page nos. on ebook.

5

Tate Modern, “Pop Art,” undated, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/pop-art; Museum of Modern Art

(MoMA), “Pop Art,” undated, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/pop-art/.

6

Sandra Zalman, Consuming Surrealism in American Culture, 81.

7

Danchev, Magritte, (page no. needed).

8

George Basalla, The Evolution of Technology (Cambridge, 1988), vii.

9

Henry Torczyner, Magritte: Ideas and Images (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1977), 68.

10

Zalman, Consuming Surrealism, 85.

11

Paul McCartney, “Paintings on the Wall—René Magritte (1898-1967),” Paul McCartney, March 13,

2015, https://www.paulmccartney.com/news/new-feature-paintings-on-the-wall-rene-magritte-1898-1967.

Iolas helped launch the careers of pop artists like Andy Warhol and who also helped bring Surrealism to

the US market. (why McCartney liked Magritte).

12

Harriet Vyner, Groovy Bob, pg no.

13

Stefan Granados, Those Were the Days—the Beatles Apple Organization: An unofcial history

of the Beatles’ Apple Organization 1967-2001 (Cherry Red Books, 2002) https://web.archive.org/

web/20070829121144/http://www.cherryred.co.uk/books/thoseweretheday_txt.php.

14

Barry Miles, “Why The Beatles Created Apple Music: Inside the music industry’s rst artist-backed

startup,” Medium, September 27, 2016, https://medium.com/cuepoint/from-apple-to-zapple-44e6653a169f.

15

Jeremy Roberts, The Beatles: Music Revolutionaries (Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books,

2011), 64.

16

They also wanted greater freedom from their record label, EMI, to shape their brand.

17

Mikal Gilmore, “Why the Beatles Broke Up: The inside story of the forces that tore apart the world’s

greatest band,” Rolling Stone, September 3, 2009, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/

why-the-beatles-broke-up-113403/.

18

Allan Kozinn, “An Exhibition of Drawings Celebrates Lennon at 64,” New York Times, October 7, 2004,

https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/07/arts/design/an-exhibition-of-drawings-celebrates-lennon-at-64.html.

19

Miles, “Why The Beatles Created Apple Music.”

20

Gilmore, “Why the Beatles Broke Up.”

21

Walter Isaac’s Steve Jobs biography.

22

Phil Lapsley, “The Denitive Story of Steve Wozniak, Steve Jobs, and Phone Phreaking,” The Atlantic,

February 20, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/02/the-denitive-story-of-steve-

wozniak-steve-jobs-and-phone-phreaking/273331/; Ron Rosenbaum, “‘Secrets of the Little Blue Box’:

The 1971 Article about Phone Hacking that Inspired Steve Jobs,” Slate, October 7, 2011, http://www.slate.

com/articles/technology/the_spectator/2011/10/the_article_that_inspired_steve_jobs_secrets_of_the_little_

blue_.html

23

While some speculated that the pair chose the name Apple so that the company would come before Atari

in the phonebook, others claimed that Jobs was inspired by one of his favourite bands, the Beatles.

24

Alessandra Pellegrino Puilt, “The Contentious Legal History Between the Apple Corps and Apple

Computer,” Pace Intellectual Property, Sports & Entertainment Law Forum, July 19, 2018, https://pipself.

blogs.pace.edu/2018/07/19/the-contentious-legal-history-between-the-apple-corps-and-apple-computer/.

25

Bryan Wawzenek, “25 Years Ago: The Beatles’ Apple Corps Reaches a New Settlement with Apple

Computer,” Ultimate Classic Rock, October 11, 2016, https://ultimateclassicrock.com/apple-corp-apple-

computers-second-settlement/

26

Eric Pfanner, “British Court Hears Apple v. Apple and ‘Le Freak,’” New York Times, March 30, 2006,

C1.

27

Steve Jobs introduces the iPhone (2007): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gt6bT3PpS1Y.

28

“Apple settles dispute with Beatles over trademark—Technology & Media—International Herald

Tribune,” New York Times, February 5, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/05/technology/05iht-

apple-web.4475971.html.

29

Brad Stone, “Settlement Lets Apple Use ‘iPhone,’” New York Times, February 22, 2007, https://www.

nytimes.com/2007/02/22/technology/22apple.html.

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

9

Creative Commons Copyright: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)