Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for

Families on Work Requirements

Unworkable & Unwise:

KALI GRANT, FUNKE ADERONMU,

SOPHIE KHAN, KAUSTUBH CHAHANDE,

CASEY GOLDVALE, INDIVAR DUTTA-GUPTA,

AILEEN CARR, & DOUG STEIGER

REVISED FEBRUARY 1, 2019

WORKING PAPER

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 2

Copyright

Creative Commons (cc) 2019 by Kali Grant, Funke Aderonmu, Sophie Khan, Kaustubh

Chahande, Casey Goldvale, Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Aileen Carr, & Doug Steiger.

Notice of rights: This report has been published under a Creative Commons license. This

work may be copied, redistributed, or displayed by anyone, provided that proper

attribution is given and that the adaptation also carries a Creative Commons license.

Commercial use of this work is disallowed.

Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality

The Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality (GCPI) works with

policymakers, researchers, practitioners, advocates, and people with lived

experience to develop effective policies and practices that alleviate poverty

and inequality in the United States.

GCPI conducts research and analysis, develops policy and programmatic

solutions, hosts convenings and events, and produces reports, briefs, and

policy proposals. We develop and advance promising ideas and identify risks

and harms of ineffective policies and practices, with a cross-cutting focus on

racial and gender equity.

The work of GCPI is conducted by two teams: the Initiative on Gender Justice

and Opportunity and the Economic Security and Opportunity Initiative.

Economic Security and Opportunity Initiative at GCPI

The mission of GCPI’s Economic Security and Opportunity Initiative

(ESOI) is to expand economic inclusion in the United States through

rigorous research, analysis, and ambitious ideas to improve

programs and policies. Further information about GCPI’s ESOI is

available at www.georgetownpoverty.org.

Please refer any questions or comments to

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 3

Acknowledgements & Disclosures

We appreciate the generous assistance provided by the following individuals,

who shared their insights and advice, some of whom reviewed drafts of this

report: Elizabeth Lower-Basch, Elayne Weiss, Ellen Vollinger, Elisa Minoff, Kate

Bahn, LaDonna Pavetti, Kelly Whitener, Rachel Black, and TJ Sutcliffe. We also

thank those who attended the convening on these issues on September 7, 2018

for their insights and expertise.

We thank Isabella Camacho-Craft and Cara Brumfield for significant research,

writing, and editing assistance, and Danny Vinik for assistance with citations.

Any errors of fact or interpretation remain the authors’.

We are grateful to the Annie E. Casey Foundation for its support for our

research and analysis of work requirements and the JPB Foundation for its

support of our cross-cutting idea development and other work. The views

expressed are those of the GCPI ESOI authors and should not be attributed to

our advisors or funders. Funders do not affect research findings or the insights

and recommendations of GCPI’s ESOI.

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 4

Contents

Acknowledgements & Disclosures ......................................................................................................3

Contents ............................................................................................................................................4

Abbreviations, Acronyms, & Initializations ..........................................................................................7

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................8

Medicaid, SNAP, & Housing Assistance Ensure a Foundation for Families............................................... 8

Removing Access to Health Care, Food, & Housing Assistance Is Counterproductive ........................... 11

Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................. 13

Policy Recommendations ........................................................................................................................ 14

Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 16

Medicaid, SNAP, & Housing Assistance Ensure a Foundation for Families............................................. 16

Removing Access to Health Care, Food, & Housing Assistance Is Counterproductive ........................... 17

Taking Assistance Away From Participants Who Do Not Meet Work Requirements is Ill-Informed...... 19

Our Economic Security System is Already Heavily Tied to Formal Employment .................................... 19

Nearly All Program Participants Have Worked, Still Work, & Will Work in the Future—or Face Major

Barriers to Work, Due to Factors Such as Age or Disability .................................................................... 21

Participants Face Barriers to Employment That Work Requirements Ignore ......................................... 22

Medicaid, SNAP, & Housing Assistance Support Work ........................................................................... 28

Medicaid Supports Work .................................................................................................................... 28

SNAP Supports Work ........................................................................................................................... 29

Housing Assistance Supports Work .................................................................................................... 29

Medicaid, Snap, & Housing Assistance Improve Labor Market Outcomes for the Next Generation 30

The Details of Harsh Work Requirement Proposals Make Little Sense for Low-Paid Workers .............. 31

Low-Wage Employers Routlinely Provide Uneven & Insufficient Work Hours .................................. 32

Low-Paid Workers Have Limited Control over Their Work Hours ...................................................... 32

Punitive, Inflexible Rules Are Poorly Aligned with the Low-Wage Labor Market .............................. 33

New Rules Can Make Medicaid Access Impossible for Some ............................................................. 33

Taking Benefits Away from People Who Do Not Meet a Work Requirement is Ineffective .................. 34

Removing People Unable to Meet a Work Requirement from Vital, Work-Supporting Programs Has

Limited Effects on Employment .............................................................................................................. 34

Available Evidence Suggests That Few Will Benefit, but Many Will Lose Needed Supports ............. 34

Increasing Employment & Incomes Requires Resources & Strategies Not Provided by Work

Requirements ...................................................................................................................................... 35

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 5

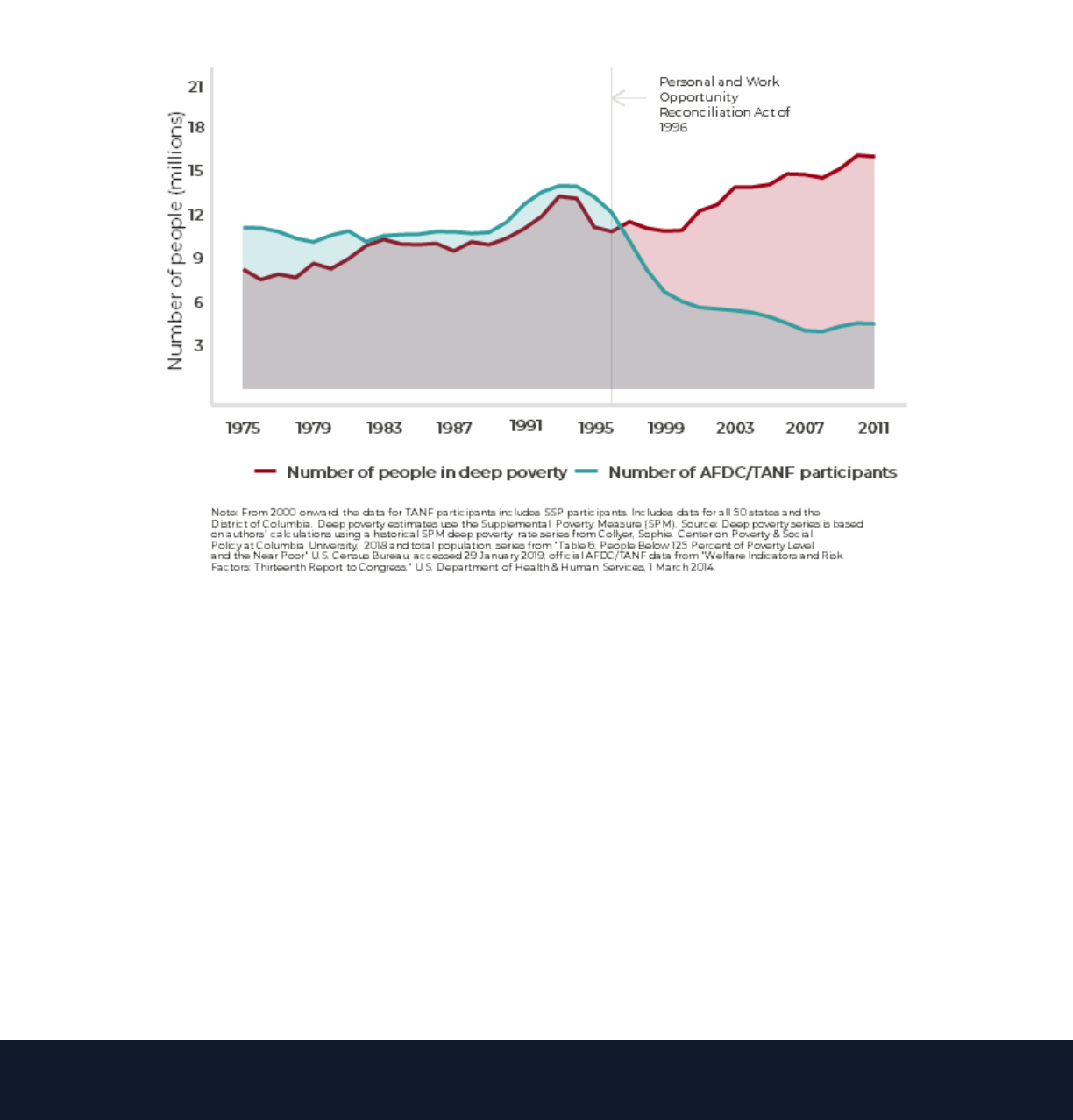

Work Requirements Fail to Reduce Poverty & May Even Increase Poverty by Weakening Foundational

Programs ................................................................................................................................................. 37

Deep Poverty is Likely to Rise as a Result of Work Requirements Weakening Foundational Programs 37

Work Requirements Lack Important Guardrails for States & Undermine Already-Effective Programs . 39

Revoking Access to Work-Supporting Programs Due to Rigid & Impractical Work Requirements is

Inefficient ........................................................................................................................................ 41

States Make it Difficult to Comply with Work Requirements ................................................................. 41

Work Rules Impose Cumbersome Requirements on Participants, Regardless of Employment Status

............................................................................................................................................................. 41

Participants Bear the Burden of Navigating Unreliable & Uneven Exemption Processes ................. 43

Work Requirements Are Burdensome for States & Their Limited Resources ........................................ 45

States Are Ill-Equipped to Administer Work Requirements ............................................................... 46

Proposals That Take Benefits Away from People Who Do Not Meet a Work Requirement May

Increase Costs for States ..................................................................................................................... 47

Work Requirements Fail to Consider Macroeconomic Ramifications for States ............................... 48

Policies to Take Benefits Away from Recipients Who Do Not Meet a Work Requirement Are

Inequitable ...................................................................................................................................... 51

Work Requirements Disparately Harm Groups Who Experience Systemic Oppression ........................ 51

People Living with Disabilities & Chronic Health Conditions .............................................................. 51

People of Color .................................................................................................................................... 52

Women ................................................................................................................................................ 54

LGBTQ Individuals ............................................................................................................................... 54

Older Adults ........................................................................................................................................ 55

Other Groups Experiencing Deep Economic Insecurity Will be Disparately Harmed by Work

Requirements .......................................................................................................................................... 55

Low-Income Caregivers & Their Families ............................................................................................ 55

People with Criminal Justice System Involvement ............................................................................. 56

Former Foster Youth ........................................................................................................................... 56

Victim-Survivors of DV/IPV, Trauma, & Violence ............................................................................... 57

Veterans with Disabilities.................................................................................................................... 57

Work Requirements Are Likely to Harm People, Families, & Communities Struggling the Most .......... 57

Damage To Well-Being of Families & Children ................................................................................... 58

Increase In Economic Insecurity & Hardship ...................................................................................... 59

Health Outcomes Likely to Worsen .................................................................................................... 59

Fewer Federal Resources Flowing into Left-Behind Communities ..................................................... 60

An Agenda to Increase Employment & Earnings Would Look Very Different ...................................... 62

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 6

Ensure a Foundation for Individuals & Families ...................................................................................... 62

Ensure Access to Work Supports like Medicaid, SNAP, & Housing, Including Expanding Medicaid in

All States .............................................................................................................................................. 62

Strengthen TANF ................................................................................................................................. 63

Raise the Minimum Wage (Including for Tipped Workers & People with Disabilities) ...................... 63

Strengthen Family Stability ..................................................................................................................... 64

Reform Unemployment Insurance & Establish a Jobseeker’s Allowance .......................................... 64

Ensure Access to Quality, Decent Jobs & Fair Labor Standards.......................................................... 65

Reform the Criminal Justice System ................................................................................................... 65

Support Workers ..................................................................................................................................... 66

Expand Proven Workforce Development Funding & Reach ............................................................... 66

Develop Subsidized & Public Employment Programs to Address Barriers to Employment, Including

Place-Based Disparities ....................................................................................................................... 67

Expand Child Care Assistance ............................................................................................................. 67

Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) ..................................................................................... 68

Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................... 69

Appendices ...................................................................................................................................... 70

Appendix A. Medicaid ............................................................................................................................. 70

Summary of Medicaid Waivers Permitting State Work Requirements .............................................. 70

Summary of Approved Medicaid Work Requirement Policies ........................................................... 73

Appendix B. SNAP .................................................................................................................................... 78

Existing SNAP Work Requirements ..................................................................................................... 78

2018 House Republican Farm Bill SNAP Work Requirement Proposal............................................... 78

The Trump Administration’s Proposed Rule on Time Limits .............................................................. 79

Appendix C. Housing................................................................................................................................ 81

Trump Administration FY2018 Budget Proposal ................................................................................ 81

Trump Administration FY2019 Budget Proposal ................................................................................ 82

Making Affordable Housing Work Act of 2018 ................................................................................... 82

Fostering Stable Housing Opportunities Act of 2018 ......................................................................... 82

HUD Moving-To-Work Demonstrations.............................................................................................. 83

HUD Public Housing Community Service and Self-Sufficiency Requirement ..................................... 83

Endnotes ......................................................................................................................................... 84

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 7

Abbreviations, Acronyms, & Initializations

ABAWDs—Able-Bodied Adults without

Dependents

ACA—Affordable Care Act (Patient Protection

and Affordable Care Act)

AFDC—Aid to Families with Dependent Children

AIAN—American Indians and Alaska Natives

CCDBG—Child Care and Development Block

Grant

CCDF—Child Care and Development Fund

CDC—Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention

CEA—Council of Economic Advisers

CMS—Centers for Medicare and Medicaid

Services

HHS—U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services

DV/IPV—Domestic Violence/Intimate Partner

Violence

EITC—Earned Income Tax Credit

EPSDT—Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic

and Treatment

FY—Fiscal Year

GA—General Assistance

GAO—U.S. Government Accountability Office

HUD—U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development

IHS—Indian Health Service

Jobseeker’s Allowance—JSA

LGBTQ—Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender,

Queer

MTW—Moving to Work Demonstration

PHA—Public Housing Authority

SNAP—Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program

SSBG—Social Services Block Grant

SSDI—Social Security Disability Insurance

SSI—Supplemental Security Income

TANF—Temporary Assistance for Needy

Families

UI—Unemployment Insurance

USDA—U.S. Department of Agriculture

WIOA—Workforce Innovation and Opportunity

Act

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 8

Executive Summary

n recent years, the Trump Administration, members of Congress, governors, and state legislatures

have put forward, and in some cases implemented, new and harsher proposals to take away health

care, food, and housing assistance from people who do not meet a work requirement. The programs

being targeted for new work requirements—Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), and housing assistance—are lifelines for individuals and families during times without sufficient

work or earnings. Because these proposals reflect misunderstandings of these programs and

participants, they are or will be harmful to the well-being of people with low incomes. These policies

differ substantially from program to program and state to state, and variations are likely to continue to

appear. Regardless, the policies all suffer from the same flaws inherent in conditioning foundational

support on documenting and participating in approved activities. As a result, this report focuses on

these policies generally rather than on any particular one (though some key policies are described in the

Appendix). In addition, alongside proposed restrictions for immigrants’ access to,

i

budget cuts for,

ii

and

the ending of other participant protections in economic security programs,

iii

these new work rules are

part of a broader strategy of gatekeeping, shrinking, and undermining the system of supports for

struggling individuals and families.

iv

The connection to other proposals, often proposed with similar

rationales and based on similar misunderstandings of programs and participants, suggests a need to

detail the sizeable body of evidence of the effectiveness of Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance in

supporting people with low incomes as they overcome challenges they face.

Medicaid, SNAP, & Housing Assistance Ensure a Foundation for Families

Research on the effects of economic security programs strongly suggests that every individual and every

family require a stable and strong foundation to be healthy and succeed in the labor market and

i

Fremstad, Shawn. “Trump’s ‘Public Charge’ Rule Would Radically Change Legal Immigration.” Center for American

Progress, 27 November 2018. Available at

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2018/11/27/461461/trumps-public-charge-rule-

radically-change-legal-immigration/.

ii

Parrott, Sharon et al. “Trump Budget Deeply Cuts Health, Housing, Other Assistance for Low- and Moderate-

Income Families.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 14 February 2018. Available at

https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/trump-budget-deeply-cuts-health-housing-other-assistance-for-

low-and.

iii

These proposals include turning Medicaid into a block grant and efforts to move HUD away from its focus on

housing discrimination. See: “Trump Administration Plans Effort to Let States Remodel Medicaid.” Wall Street

Journal, 11 January 2019. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-administration-plans-effort-to-let-

states-remodel-medicaid-11547259197 and “Ben Carson is Pulling HUD Away From its Key Mission.” Vox, 11 April

2018. Available at https://www.vox.com/identities/2018/3/8/17093136/ben-carson-hud-discrimination-fair-

housing-anniversary.

iv

See for example the discussion of cuts, work requirements, and restructuring of economic security programs

here: Golden, Olivia. “Moving America’s Families Forward: Setting Priorities for Reducing Poverty and Expanding

Opportunity.” Testimony presented to the Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives, 24 May

2016. Available at https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/publication-

1/2016-05-24-Olivia-Golden-Testimony-to-House-Ways-and-Means.pdf.

I

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 9

beyond.

v

,

vi

,

vii

,

viii

That foundation, especially for people struggling in the labor market, is often ensured

through public benefits and services, including Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance. These programs

have demonstrated beneficial long-term, intergenerational effects on employment and earnings for the

children in families who participate.

ix

,

x

,

xi

,

xii

By providing economic security for disadvantaged individuals

and families, Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance also advance economic opportunity.

Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance programs provide essential services and support to tens of

millions of individuals and families in the United States. In 2010, Medicaid kept at least 2.6 to 3.4 million

people out of poverty.

xiii

In 2017, SNAP and housing subsidies kept 3.4 million and 2.9 million people out

of poverty, respectively (all by the Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM).

xiv

Medicaid is a federal-state

partnership that provides health coverage for more than 1 in 5 people in the United States, including

v

Hoynes, Hilary, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond. "Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to

the Safety Net." American Economic Review, April 2016. Available at

https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/Hoynes-Schanzenbach-Almond-AER-2016.pdf.

vi

Bivens, Josh, and Shawn Fremstad. "Why Punitive Work-Hours Tests in SNAP and Medicaid Would Harm Workers

and Do Nothing to Raise Employment." Economic Policy Institute, 26 July 2018. Available at

https://www.epi.org/publication/why-punitive-work-hours-tests-in-snap-and-medicaid-would-harm-workers-and-

do-nothing-to-raise-employment/.

vii

Sherman, Arloc, and Tazra Mitchell. "Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long

Term, Many Studies Find." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 17 July 2017. Available at

https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-

succeed-over.

viii

Carlson, Steven, and Zoe Neuberger. "WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income

Families for 40 Years." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated 29 March 2017. Available at

https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-works-addressing-the-nutrition-and-health-needs-of-low-

income-families.

ix

Hoynes, Hilary, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond. "Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to

the Safety Net." American Economic Review, April 2016. Available at

https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/Hoynes-Schanzenbach-Almond-AER-2016.pdf.

x

Sherman, Arloc, and Tazra Mitchell. "Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long

Term, Many Studies Find." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 17 July 2017. Available at

https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-

succeed-over.

xi

Brown, David W., Amanda E. Kowalski, and Ithai Z. Lurie. "Medicaid as an Investment in Children: What is the

Long-Term Impact on Tax Receipts?" NBER Working Paper No. 20835, January 2015. Available at

https://www.nber.org/papers/w20835.pdf.

xii

Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz. "The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on

Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Project." American Economic Review 106(4): 855-902,

August 2015. Available at https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/aer.20150572.

xiii

Sommers, Benjamin D., and Donald Oellerich. "The poverty-reducing effect of Medicaid." Journal of Health

Economics, 32(5): 816-832, September 2013. Available at

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016762961300091X.

xiv

Fox, Liana. "The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2016." U.S. Census Bureau, revised September 2017. Available

at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/demo/p60-261.pdf.

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 10

millions of low-wage workers and their families

xv

and people in need of long-term support and

services.

xvi

Medicaid provides vital health care coverage to many who would otherwise lack it. SNAP is

state-administered and largely federally-funded, helping approximately 1 in 8 people in the U.S.

xvii

purchase food—including many who are at greatest risk of experiencing hunger or poor nutrition.

xviii

Federally-funded housing assistance provides rental aid for some households with the lowest incomes

and is generally administered through local housing authorities, who in turn provide vouchers, directly

subsidize units in private housing developments, or build and maintain public housing

xix

for fewer than 1

in 30 people in the U.S.

xx

Particularly in light of the decline of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF)

xxi

and General Assistance (GA),

xxii

which provide cash assistance to families and individuals

respectively, and the challenges of today’s low-wage labor market, these programs are essential for

ensuring that people do not fall below a floor for material deprivation or economic resources.

xxiii

xv

Garfield, Rachel, Robin Rudowitz, and Anthony Damico. “Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work.”

Kaiser Family Foundation, 5 January 2018. Available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-

the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work/.

xvi

Rudowitz, Robin, and Rachel Garfield. "10 Things to Know about Medicaid: Setting the Facts Straight." Kaiser

Family Foundation, 12 April 2018. Available at https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-

medicaid-setting-the-facts-straight/.

xvii

"Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Costs." Food and Nutrition Service, U.S.

Department of Agriculture, 7 December 2018. Available at https://fns-

prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/pd/SNAPsummary.pdf.

xviii

Kearney, Melissa S., and Benjamin H. Harris. "Hunger and the Important Role of SNAP as Part of the American

Safety Net." Brookings Institute, 22 November 2013. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-

front/2013/11/22/hunger-and-the-important-role-of-snap-as-part-of-the-american-safety-net/.

xix

"Policy Basics: Federal Rental Assistance." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated 15 November 2017.

Available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/policy-basics-federal-rental-assistance.

xx

Authors’ calculation using data at "Assisted Housing: National and Local." Office of Policy Development and

Research, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, retrieved 17 December 2018. Available at

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/assthsg.html#2009-2017_query; "Section 521 Rental Assistance:

Households Members." U.S. Department of Agriculture, 6 April 2018. Available at

https://www.rd.usda.gov/files/RDUL-MFHannual.pdf; "U.S. and World Population Clock." U.S. Census Bureau,

updated 25 January 2019. Available at https://www.census.gov/popclock/.

xxi

Dutta-Gupta, Indi, and Kali Grant. “TANF’s Not All Right.” The Hill, 30 April 2015. Available at

https://thehill.com/opinion/op-ed/240666-tanfs-not-all-right.

xxii

“In recent decades, a number of states have eliminated their General Assistance programs, while many others

have cut funding, restricted eligibility, imposed time limits, and/or cut benefits.” See: Schott, Liz, and Misha Hill.

“State General Assistance Programs Are Weakening Despite Increasing Need.” Center for Budget and Policy

Priorities, 9 July 2015. Available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/state-general-

assistance-programs-are-weakening-despite-increased.

xxiii

Shaefer, H. Luke, et al. "The Decline of Cash Assistance and the Well-Being of Households with Children."

Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan, 28 August 2018. Available at https://poverty.umich.edu/working-

paper/the-decline-of-cash-assistance-and-the-well-being-of-households-with-children/.

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 11

Removing Access to Health Care, Food, & Housing Assistance Is

Counterproductive

Work requirements in programs ensuring a basic foundation for people have a long history of poor

outcomes, though recent proposals are unprecedented. New work requirements are inspired in part by

similar policies imposed on TANF recipients since 1996 that likely have contributed to increases in deep

poverty, as detailed later in this report.

SNAP and housing assistance programs have had some requirements related to work activities for some

participants in the past, but the proposals discussed in this paper would make them harsher and include

a far larger share of participants. At the federal level, longstanding SNAP time limits have substantially

limited access for many unemployed and underemployed adults, though states have routinely applied

for and received waivers from these draconian provisions.

xxiv

In 2016, about half a million participants

lost food assistance because they failed to meet a SNAP work time limit.

xxv

Recent proposals would

make these SNAP rules harsher still.

xxvi

Federally-funded housing assistance programs have

experimented with requirements related to work activities through demonstrations, but never as a part

of widely-applicable policy.

xxvii

(For the purposes of this paper, “housing assistance programs” refer to

Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers, Public Housing, and Project-Based Rental Assistance programs.)

Until now, Medicaid had never been tied to formal employment; its central purpose is to provide health

coverage to people with very low incomes. Removing participants and leaving them uninsured due to

not meeting or documenting work or community engagement activities is thus new to Medicaid. As of

January 2019, 16 states have applied for, and one has implemented, work requirements in Medicaid;

this number is expected to grow.

xxviii

(The legal question of whether applying such requirements through

Medicaid state waivers is consistent with the program’s purpose of providing medical care and

treatment is the subject of ongoing litigation, as discussed in the Appendix.)

xxix

Efforts to take benefits away from many more participants in Medicaid, SNAP, or housing assistance

programs misunderstand the populations such programs aim to serve and grossly underestimate the

xxiv

Bolen, Ed, and Stacy Dean. “Waivers Add Key State Flexibility to SNAP’s Three-Month Time Limit.” Center for

Budget and Policy Priorities, 6 February 2018. Available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-

assistance/waivers-add-key-state-flexibility-to-snaps-three-month-time-limit.

xxv

Bolen, et al. “More than 500,000 Adults Will Lose SNAP Benefits in 2016 as Waivers Expire.” 2016.

xxvi

Paquette, Danielle, and Jeff Stein. "Trump Administration Aims to Toughen Work Requirements for Food Stamp

Recipients." Washington Post, 20 December 2018. Available at

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/trump-administration-aims-to-toughen-work-

requirements-for-food-stamps-recipients/2018/12/20/cf687136-03e6-11e9-b6a9-

0aa5c2fcc9e4_story.html?noredirect=on.

xxvii

Jan, Tracy. "Trump Wants More People Who Receive Housing Subsidies to Work." Washington Post, 23 May

2017. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/05/23/for-the-first-time-poor-people-

receiving-housing-subsidies-may-be-required-to-work/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.a98e8b97d80f.

xxviii

“State Waivers List.” Medicaid.gov, Retrieved 15 January 2019. Available at

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/demonstration-and-waiver-list/index.html.

xxix

Rosenbaum, Sara. “Stewart v. Azar and the Future of Medicaid Work Requirements.” Commonwealth Fund, 3

July 2018. Available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/future-of-Medicaid-work-requirements.

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 12

harm to families and individuals as a result of these policies. The new policies also ignore the structural

barriers people with very low incomes face, including the unavailability of full-time work and the

instability of low-wage jobs today.

xxx

Alongside a 3.9 percent December 2018 unemployment rate, 7.6

percent

xxxi

(12.8 million people)

xxxii

of the civilian labor force plus marginally-attached

xxxiii

workers was

unemployed or underemployed.

xxxiv

At the same time, many communities of color continue to face

recession-like circumstances despite a lengthy period of economic growth for the U.S. For example, the

December 2018 unemployment rate for African Americans was 6.6 percent

xxxv

—a figure that, as a

statewide unemployment rate, could be high enough to trigger permanent law Extended Benefits under

the Unemployment Insurance (UI) program.

xxxvi

This high African American unemployment rate comes

more than 114 months into an economic expansion, the second longest in U.S. recorded economic

history.

xxxvii

These indicators reveal a strong desire for greater employment than offered or available in

what otherwise may seem to some to be a full-employment labor market.

As a result, low-paid workers, people of color,

xxxviii

people with disabilities or chronic health conditions

(including mental health conditions and substance use disorders),

xxxix

people with criminal records,

xl

and

xxx

Hahn, Heather. “Work Requirements in Safety Net Programs: Lessons for Medicaid from TANF and SNAP.”

Urban Institute, April 2018. Available at

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98086/work_requirements_in_safety_net_programs_0.pdf.

xxxi

Author’s calculations. See: “Databases, Tables and Calculators by Subject.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S.

Department of Labor, retrieved 26 January 2019. Available at https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS13327709.

xxxii

“Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of

Labor, updated 4 January 2019. Available at https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpseea03.htm.

xxxiii

“BLS Information: Glossary.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, updated 7 June 2016.

Available at https://www.bls.gov/bls/glossary.htm.

xxxiv

These workers were either unemployed; employed part-time for economic reasons; or were available for work,

had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months (or since the end of their last job if they held one within the

past 12 months), but were not counted as unemployed because they had not searched for work in the prior 4

weeks.

xxxv

“Unemployment Rate: Black or African American (LNS14000006).” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and Bureau

of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, retrieved 26 January 2019. Available at

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS14000006.

xxxvi

Whittaker, Julie M., and Katelin P. Isaacs. “Unemployment Insurance: Programs and Benefits.” Congressional

Research Service, 27 February 2018. Available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33362.

xxxvii

“US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.” National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), retrieved 26

January 2019. Available at https://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html.

xxxviii

Hahn, Heather, et al. “Why Does Cash Welfare Depend on Where You Live? How and Why State TANF

Programs Vary.” Urban Institute, 5 June 2017. Available at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/why-

does-cash-welfare-depend-where-you-live.

xxxix

Ku, Leighton, and Erin Brantley. “Medicaid Work Requirements: Who’s at Risk?" Health Affairs, 12 April, 2017.

Available at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170412.059575/full/.

xl

Wolkomir, Elizabeth. “How SNAP Can Better Serve the Formerly Incarcerated.” Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, 16 March 2018. Available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/how-snap-can-better-

serve-the-formerly-incarcerated.

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 13

children

xli

will be harmed, rather than helped, by proposals that take food, health care, and housing

assistance away if recipients do not satisfy work requirements. These programs support and promote

work, not just for adult participants but for their children when they become adults.

xlii

Key Findings

Taking away health coverage, food, and housing support from people who are unable to either

document work-related activities, work, or find work will cause more harm than good. Many people

who are or will be affected by such requirements are already participating in the labor force, meeting

family and caregiving responsibilities, or have other serious or multiple barriers to employment.

xliii

Establishing or expanding harsh penalties (or sanctions) in programs that help ensure a basic foundation

for families promises few benefits and poses substantial costs to already-struggling people.

xliv

,

xlv

In this

report, we examine how the newly-proposed “work requirements” in Medicaid, SNAP, and housing

assistance are ill-informed, ineffective, inefficient, and inequitable, and how alternative policies would

produce outcomes that reduce poverty and increase opportunity:

• Ill-Informed. Weakening foundational programs by taking benefits away from people who do

not meet harsh work requirements ignores the realities of today’s low-wage labor market and

the systemic barriers—such as caregiving responsibilities and discrimination—standing between

people and quality, stable, and secure employment. At the same time, the majority of working-

age program participants without a work-limiting disability generally work.

xlvi

• Ineffective. Though they should be strengthened, the affected economic security programs are

designed to and already do support and enable work. Mandatory work requirements, on the

xli

“Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements Harms Children.” Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, updated 20 December 2018. Available at https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/harm-to-children-

from-taking-away-medicaid-from-people-for-not-meeting-work.

xlii

Page, Marianne. "Safety Net Programs Have Long-term Benefits for Children in Poor Households." Center for

Poverty Research, University of California, Davis, March 2017. Available at

https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/sites/main/files/file-attachments/cpr-health_and_nutrition_program_brief-

page_0.pdf.

xliii

Bauer, Lauren, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Jay Shambaugh. "Work Requirements and Safety Net

Programs." Hamilton Project, October 2018. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2018/10/WorkRequirements_EA_web_1010_2.pdf.

xliv

Pavetti, LaDonna. "TANF Studies Show Work Requirement Proposals for Other Programs Would Harm Millions,

Do Little to Increase Work." Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 13 November 2018. Available at

https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-studies-show-work-requirement-proposals-for-other-

programs-would.

xlv

Ku, Leighton, et al. “Medicaid Work Requirements: Will They Help the Unemployed Gain Jobs or Improve

Health?” The Commonwealth Fund, 6 November 2018. Available at

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2018/nov/medicaid-work-requirements-will-they-

help-jobs-health.

xlvi

Bauer, Lauren, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Jay Shambaugh. "Work Requirements and Safety Net

Programs." Hamilton Project, October 2018. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2018/10/WorkRequirements_EA_web_1010_2.pdf.

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 14

other hand, are generally ineffective at achieving their goal of reducing poverty through greater

employment and earnings.

xlvii

In fact, they likely will result in the deepening or increasing of

poverty

xlviii

and compound existing challenges with an already overburdened, underfunded

workforce system.

xlix

Because states fail to communicate effectively about how to fulfill the

burdensome documentation and reporting processes, many working participants are in danger

of losing needed benefits and services.

• Inefficient. Work requirements are costly to administer and time-intensive for all involved.

Program administrators will spend more time implementing these requirements than focusing

on supporting the health, housing, and income support needs of participants. Furthermore, the

burden of proof for exemptions and compliance falls on already-struggling people. In particular,

people with disabilities who lack Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and SSI benefits and

people with substantial economic disadvantages are likely to unfairly face work requirements

and struggle to document compliance with them. These sanctions also undermine the

effectiveness of economic security programs in countering recessions.

• Inequitable. Taking away access to foundational programs from people who do not meet work

requirements puts populations that are already facing systemic discrimination or other barriers,

including children, people with disabilities, caregivers, older workers, and workers of color,

further at risk. Work requirements will deepen existing inequities, including in negative physical

and behavioral health outcomes, poverty and deep poverty, and for community-wide outcomes.

Policy Recommendations

In addition to halting and reversing counterproductive work mandates, policymakers should advance an

agenda that actually would increase employment and incomes. We propose illustrative

recommendations in three categories:

1. Ensure a foundation for individuals and families, including by ensuring access to and

strengthening programs such as SNAP, Medicaid, housing assistance, and TANF, and raising the

minimum wage;

2. Strengthen family stability, including by modernizing UI and establishing a Jobseeker’s

Allowance (JSA), establishing fair and predictable schedules as well as paid leave, and reforming

the criminal justice system; and

xlvii

Musumeci, MaryBeth, and Julia Zur. “Medicaid Enrollees and Work Requirements: Lessons from the TANF

Experience.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 18 August 2017. Available at https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-

enrollees-and-work-requirements-issue-brief.

xlviii

Sherman, Arloc. “After 1996 Welfare Law, a Weaker Safety Net and More Children in Deep Poverty.” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, 9 August 2016. Available at https://www.cbpp.org/family-income-support/after-1996-

welfare-law-a-weaker-safety-net-and-more-children-in-deep-poverty.

xlix

Rocha, Renato and Anna Cielinski. “Why the Current Workforce System is Not Suited to Help Medicaid

Beneficiaries Meet Work Requirements.” Center for Law and Social Policy, 31 October 2018. Available at

https://www.clasp.org/blog/why-current-workforce-system-not-suited-help-medicaid-beneficiaries-meet-work-

requirements.

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 15

3. Support workers, including by investing in job preparation and creation through proven training

and education, and subsidized and public employment programs; expanding child care

assistance; and boosting the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 16

Introduction

n recent years, the Trump Administration, members of Congress, governors, and state legislatures

have put forward, and in some cases implemented, new and harsher proposals to take away health

care, food, and housing assistance from people who do not meet a work requirement. The programs

being targeted for new work requirements—Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), and housing assistance—are lifelines for individuals and families during times without sufficient

work or earnings. Because these proposals reflect misunderstandings of these programs and

participants, they are or will be harmful to the well-being of people with low incomes. These policies

differ substantially from program to program and state to state, and variations are likely to continue to

appear. Regardless, the policies all suffer from the same flaws inherent in conditioning foundational

support on documenting and participating in approved activities. As a result, this report focuses on

these policies generally rather than on any particular one (though some key policies are described in the

Appendix). In addition, alongside proposed restrictions for immigrants’ access to,

1

budget cuts for,

2

and

the ending of other participant protections in economic security programs,

3

these new work rules are

part of a broader strategy of gatekeeping, shrinking, and undermining the system of supports for

struggling individuals and families.

4

The connection to other proposals, often proposed with similar

rationales and based on similar misunderstandings of programs and participants, suggests a need to

detail the sizeable body of evidence of the effectiveness of Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance in

supporting people with low incomes as they overcome challenges they face.

Medicaid, SNAP, & Housing Assistance Ensure a Foundation for Families

Research on the effects of economic security programs strongly suggests that every individual and every

family require a stable and strong foundation to be healthy and succeed in the labor market and

beyond.

5

,

6

,

7

,

8

That foundation, especially for people struggling in the labor market, is often ensured

through public benefits and services, including Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance. These programs

have demonstrated beneficial long-term, intergenerational effects on employment and earnings for the

children in families who participate.

9

,

10

,

11

,

12

By providing economic security for disadvantaged

individuals and families, Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance also advance economic opportunity.

Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance programs provide essential services and support to tens of

millions of individuals and families in the United States. In 2010, Medicaid kept at least 2.6 to 3.4 million

people out of poverty.

13

In 2017, SNAP and housing subsidies kept 3.4 million and 2.9 million people out

of poverty, respectively (all by the Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM).

14

Medicaid is a federal-state

partnership that provides health coverage for more than 1 in 5 people in the United States, including

millions of low-wage workers and their families

15

and people in need of long-term support and

services.

16

Medicaid provides vital health care coverage to many who would otherwise lack it. SNAP is

state-administered and largely federally-funded, helping approximately 1 in 8 people in the U.S.

17

purchase food—including many who are at greatest risk of experiencing hunger or poor nutrition.

18

Federally-funded housing assistance provides rental aid for some households with the lowest incomes

and is generally administered through local housing authorities, who in turn provide vouchers, directly

subsidize units in private housing developments, or build and maintain public housing

19

for fewer than 1

in 30 people in the U.S.

20

Particularly in light of the decline of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF)

21

and General Assistance (GA),

22

which provide cash assistance to families and individuals

I

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 17

respectively, and the challenges of today’s low-wage labor market, these programs are essential for

ensuring that people do not fall below a floor for material deprivation or economic resources.

23

Removing Access to Health Care, Food, & Housing Assistance Is

Counterproductive

Work requirements in programs ensuring a basic foundation for people have a long history of poor

outcomes, though recent proposals are unprecedented. New work requirements are inspired in part by

similar policies imposed on TANF recipients since 1996 that likely have contributed to increases in deep

poverty, as detailed later in this report.

SNAP and housing assistance programs have had some requirements related to work activities for some

participants in the past, but the proposals discussed in this paper would make them harsher and include

a far larger share of participants. At the federal level, longstanding SNAP time limits have substantially

limited access for many unemployed and underemployed adults, though states have routinely applied

for and received waivers from these draconian provisions.

24

In 2016, about half a million participants

lost food assistance because they failed to meet a SNAP work time limit.

25

Recent proposals would make

these SNAP rules harsher still.

26

Federally-funded housing assistance programs have experimented with

requirements related to work activities through demonstrations, but never as a part of widely-applicable

policy.

27

(For the purposes of this paper, “housing assistance programs” refer to Section 8 Housing

Choice Vouchers, Public Housing, and Project-Based Rental Assistance programs.) Until now, Medicaid

had never been tied to formal employment; its central purpose is to provide health coverage to people

with very low incomes. Removing participants and leaving them uninsured due to not meeting or

documenting work or community engagement activities is thus new to Medicaid. As of January 2019, 16

states have applied for, and one has implemented, work requirements in Medicaid; this number is

expected to grow.

28

(The legal question of whether applying such requirements through Medicaid state

waivers is consistent with the program’s purpose of providing medical care and treatment is the subject

of ongoing litigation, as discussed in the Appendix.)

29

Efforts to take benefits away from many more participants in Medicaid, SNAP, or housing assistance

programs misunderstand the populations such programs aim to serve and grossly underestimate the

harm to families and individuals as a result of these policies. The new policies also ignore the structural

barriers people with very low incomes face, including the unavailability of full-time work and the

instability of low-wage jobs today.

30

Alongside a 3.9 percent December 2018 unemployment rate, 7.6

percent

31

(12.8 million people)

32

of the civilian labor force plus marginally-attached

33

workers was

unemployed or underemployed.

34

At the same time, many communities of color continue to face

recession-like circumstances despite a lengthy period of economic growth for the U.S. For example, the

December 2018 unemployment rate for African Americans was 6.6 percent

35

—a figure that, as a

statewide unemployment rate, could be high enough to trigger permanent law Extended Benefits under

the Unemployment Insurance (UI) program.

36

This high African American unemployment rate comes

more than 114 months into an economic expansion, the second longest in U.S. recorded economic

history.

37

These indicators reveal a strong desire for greater employment than offered or available in

what otherwise may seem to some to be a full-employment labor market.

As a result, low-paid workers, people of color,

38

people with disabilities or chronic health conditions

(including mental health conditions and substance use disorders),

39

people with criminal records,

40

and

children

41

will be harmed, rather than helped, by proposals that take food, health care, and housing

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 18

assistance away if recipients do not satisfy work requirements. These programs support and promote

work, not just for adult participants but for their children when they become adults.

42

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 19

Taking Assistance Away From Participants

Who Do Not Meet Work Requirements is

Ill-Informed

his section considers the appropriateness of taking away healthcare, food assistance, or housing

assistance if people fail to meet and document work and community engagement requirements—

typically a set number of hours in an approved activity each month—as an anti-poverty policy approach

within the context of broader social, economic, and other relevant factors. It outlines the ways in

which rationales for work requirements for some Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance

participants fall short of appreciating the roles, purposes, and impacts of these vital supports for

low-income people and their families. Lastly, the section examines often-mistaken or misleading

assumptions about who participates in affected programs and why, and what keeps participants from

working or earning more. These and other ill-informed assumptions about program participants are

apparent in what proponents have stated publicly as well as in the details of actual work requirements.

Our Economic Security System is Already Heavily Tied to Formal Employment

Newly proposed work-related rules in Medicaid, SNAP, and housing assistance warrant particular

attention because these programs serve as a lifeline to many left out of the rest of our economic

security system. Much of our economic security system, including health coverage and income supports,

conditions access on some demonstration of formal employment,

43

rather than primarily on need (see

Figure 1).

44

Contributory social insurance programs like Medicare,

45

Social Security (including disability

insurance, or SSDI),

46

and Unemployment Insurance

47

require individual or household earnings histories.

Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and GA taken together with Aid to Families with

Dependent Children (AFDC)—before being replaced by TANF—acted as the fallback economic security

programs for people who would not otherwise qualify for Medicare (or have access to employer-

sponsored health insurance), Social Security, and UI, primarily due to the latter programs’ requirements

of formal labor market earnings.

Even supports and services intended for those who are least able to work in formal employment, like

AFDC’s replacement, TANF, require labor-market-focused engagement for many participants.

48

As TANF

and GA have shrunk dramatically, the relatively newer Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and even more

recent Child Tax Credit (CTC), which both require formal earnings, have grown substantially. Child care

assistance has expanded and contracted over the past few decades,

49

but often targets those with

formal employment; for unemployed jobseekers, it is unavailable in several states and significantly

restricted in most of the remaining states.

50

Overall, our economic security system strongly and

increasingly requires formal work and offers less and less to those struggling to find and maintain

employment.

51

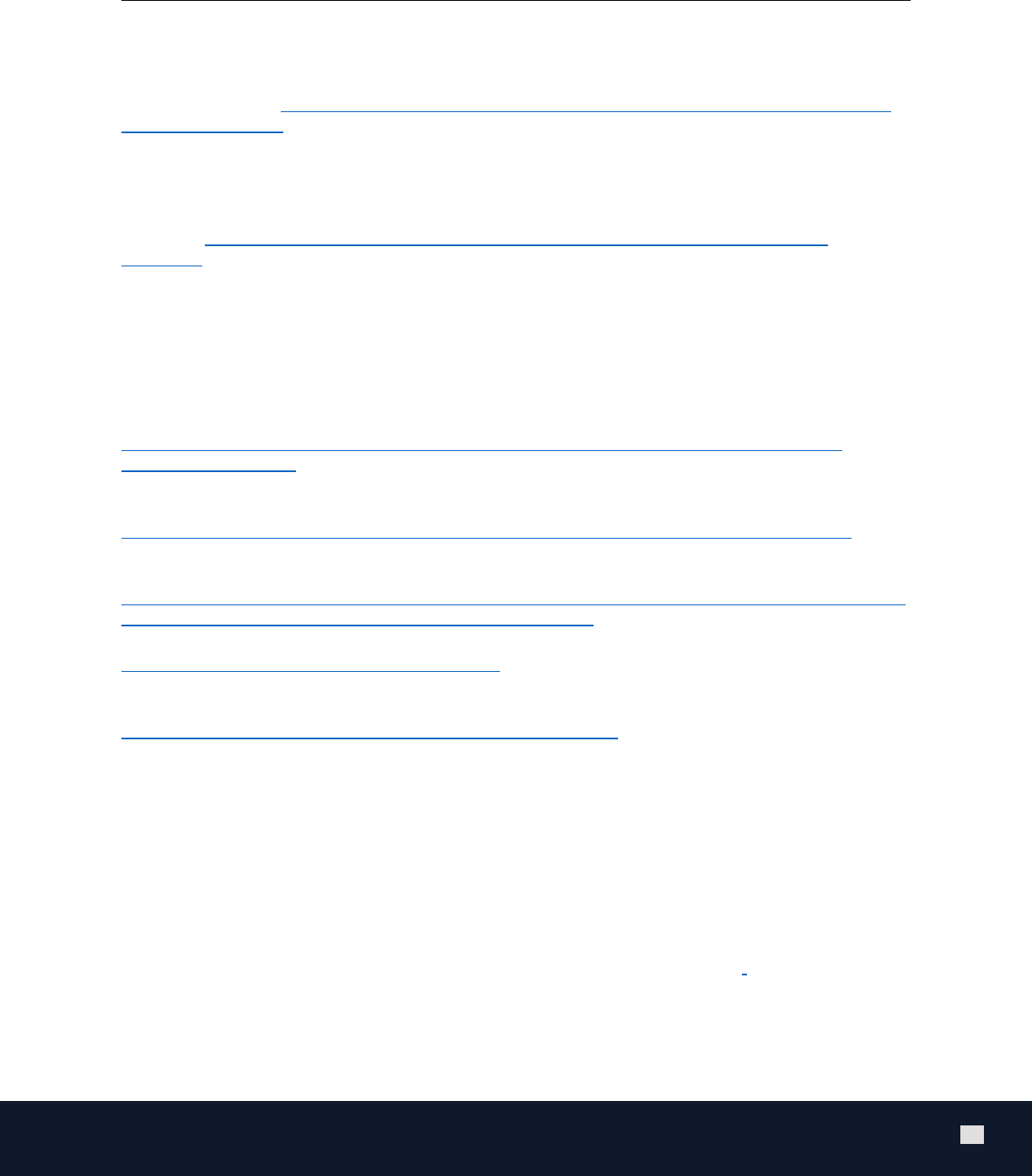

Figure 1. Major economic security programs require earnings & meeting labor-market-oriented tests

Role of labor market earnings & activities in accessing key economic support programs

T

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 20

PROGRAM

DESCRIPTION

LABOR-MARKET-RELATED ELIGIBILITY

REQUIREMENTS

Social Security (SS) &

Disability Insurance

(SSDI)

SS: Provides retirement & survivors’ benefits

for workers;

52

SSDI: Provides benefits for

individuals with a work-limiting disability

53

SS: Prior household earnings to claim; SSDI: Prior

individual earnings to claim

Medicare

Provides health insurance for individuals aged

65+, or after 2 years of SSDI receipt

54

Prior household earnings to enroll, or current

income to buy-in for citizens or permanent

residents 65 & over

UI

Provides unemployment benefits to eligible

workers

55

Prior individual earnings as employee &, generally,

documentation of current job search to claim

Working Family Tax

Credits

EITC: Credit for workers with a low to

moderate income;

56

CTC: Credit for qualifying

dependents claimed by taxpayer;

57

CDCTC:

Credit to offset child care costs

58

Current household earnings to claim EITC, CTC, &

CDCTC

CCDBG/CCDF

Provides child care assistance for low-income

families so they can work or attend a job

training or educational program

59

Typically targets people with formal employment;

unavailable for unemployed jobseekers in several

states & significantly restricted in most remaining

states

60

TANF

Provides temporary cash assistance for low-

income families with children

Participation in labor-market-oriented activities

(exemptions: single parents with children under 12

months old & parents caring for family member

with a disability

61

others differ by state)

Medicaid

Provides health insurance for qualifying low-

income individuals

Historically, no minimum earnings to claim;

recently work and community engagement

requirements proposed, approved, or

implemented in 16 states

62

SNAP

Provides nutrition assistance for eligible low-

income individuals & families

Time limits for some people without jobs of

working age if area lacks waiver;

63

USDA proposal

would limit waivers to areas where unemployment

rate is over 7%

64

Housing Assistance

Provides rental assistance for some low-

income households, through vouchers, directly

subsidized units in private housing

developments, or public housing units

No minimum earnings to claim; work

requirements in: MTW demonstration (9 PHAs),

65

president’s FY19 budget (for project-based

assistance),

66

Proposed Fostering Stable Housing

Opportunities Act of 2018 (for youth aging out of

foster care)

67

Source: Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2019

In this context, proposals to establish or expand requirements denying Medicaid, SNAP, and housing

assistance—programs that prevent destitution

68

, disease,

69

and even death

70

for the most vulnerable in

our society—because participants fail to meet and document approved work and community

engagement requirements make little sense. Determining eligibility or benefits for these programs by

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 21

requiring ongoing demonstration of formal work or work-related activities will tend to compound

disadvantage,

71

trapping rather than empowering people when they are struggling the most.

72

Nearly All Program Participants Have Worked, Still Work, & Will Work in the

Future—or Face Major Barriers to Work, Due to Factors Such as Age or Disability

The push for these new requirements reflects an incomplete understanding of the low-wage labor

market and the lived experiences of people who are attempting to navigate it to find, secure, and

maintain employment compatible with their own health and family responsibilities. A primary

assumption

73

of policies to take away benefits from participants in Medicaid, SNAP, and housing

assistance who do not meet a work requirement is that adults who should be able to work formally can

and will do so, if properly incentivized.

74

However, for all three programs, a multitude of evidence

demonstrates that most participants who can work already do. Most adults of working age who do not

have a work-limiting disability and participate in Medicaid,

75

SNAP,

76

and housing assistance

77

work or

have recently worked. For the majority (over 80 percent) of SNAP participants, who have worked before

SNAP participation and will work again (within a year of SNAP participation), SNAP provides temporary

support to help weather spells of un- or under-employment, or to help supplement low and inconsistent

pay.

78

Among SNAP recipients of working age who do not have a work-limiting disability, over 50 percent

work while receiving SNAP.

79

Among those not working, two-thirds of recipients are children, elderly

people, and people with disabilities (see Figure 2).

80

This is similar for SNAP households, among whom

about 60 percent of households with children and an adult of working age who did not have a work-

limiting disability had work earnings in 2015.

81

In fact, the proportion of SNAP participants in households

with a worker has increased sharply over the last two decades, suggesting SNAP plays a strong role in

supporting people and families during periods of underemployment.

82

Medicaid and housing assistance participants who do not qualify for disability insurance typically also

live in working households. Of the nearly 25 million working-age Medicaid recipients who do not qualify

for SSI, 8 in 10 live in working families or work themselves.

83

In 2017, 61 percent of participating non-

elderly families had at least one member employed full-time, and an additional 14 percent had someone

working at least part-time.

84

This population is likely to account for a significant share of Medicaid

recipients who would lose coverage due to the burdens of satisfying reporting requirements, as

discussed in further detail later in the paper.

85

Similarly, an analysis of federal housing assistance data

found that 88 percent of households that received rental assistance in 2010 were elderly or had

someone with a disability (55 percent), were working or had recently worked (28 percent), or were likely

to face work requirements through TANF (5 percent) as it is.

86

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 22

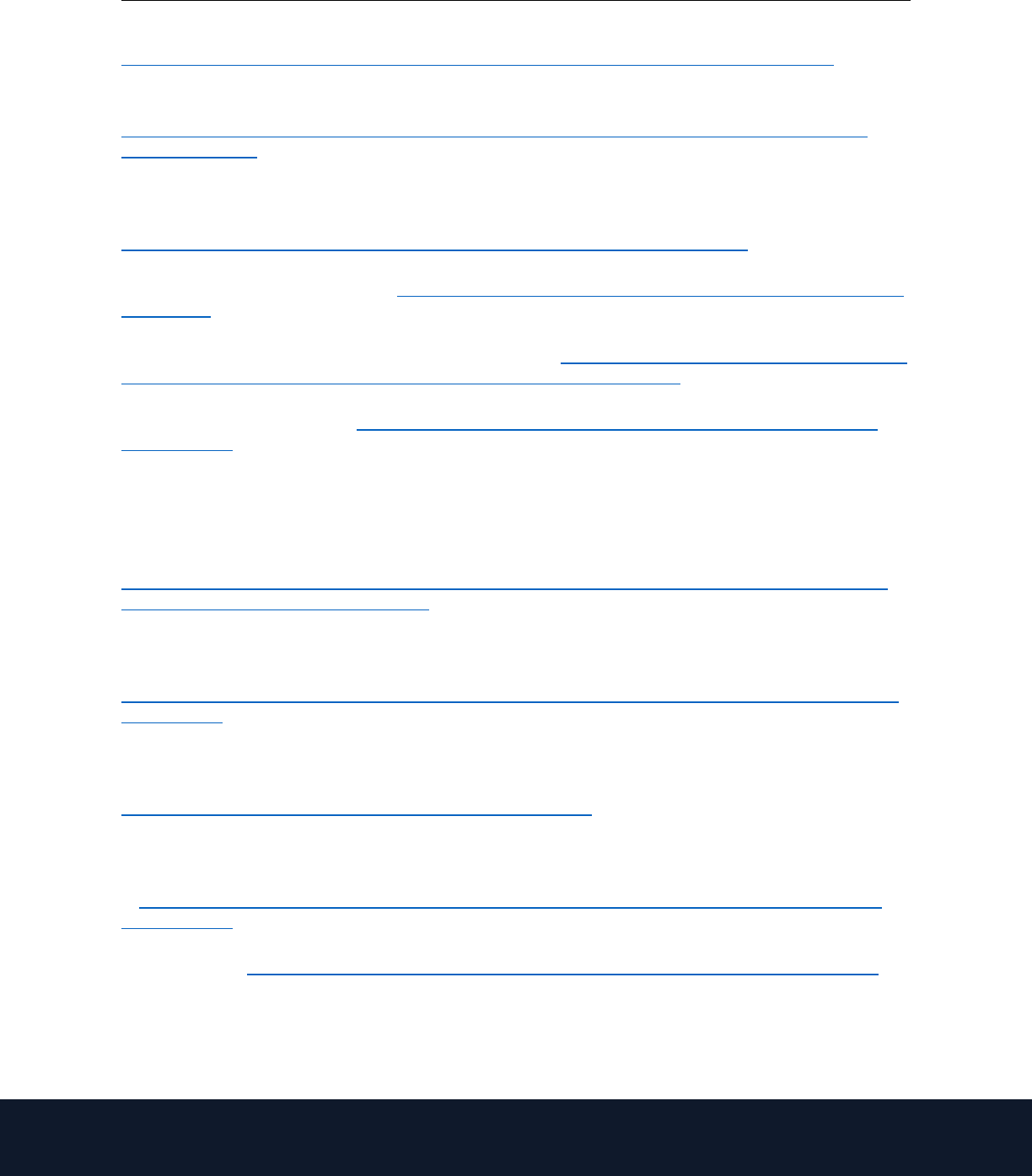

Figure 2. Vast majority of Medicaid, SNAP, & housing assistance participants not engaged in formal

employment due to caregiving, school, retirement, or sickness or disability

Main reported reason for not working among Medicaid, SNAP, & HUD-assisted housing participants,

2017

Participants Face Barriers to Employment That Work Requirements Ignore

Many program participants face barriers to employment that can make it challenging or impossible to

maintain steady employment that keeps them and their families out of poverty.

87

Some face obstacles

to work, such as significant health problems or caregiving responsibilities, not addressed adequately in

work requirement proposals.

88

Others need more advanced skills but cannot participate in education or

training without income supports,

which are in short supply for

people pursuing such

development. The remaining

individuals who are not working

face other sizeable individual

and/or structural barriers to

employment which, regardless of

economic conditions, work

requirements will not help

address.

89

,

90

Box 1.

While this paper focuses on recent iterations of work requirements

in foundational social assistance programs, the historical context is

illuminating. Modern work requirements follow a long history of

racially-motivated critiques of programs supporting living

standards; some proposals have relied on racial bias—fueled, in

part, by false narratives about African American women in

particular—to garner support.

(continued on the next page)

Box 1 cont.

THE RACIAL HISTORY OF WORK REQUIREMENTS

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 23

These barriers can be categorized roughly into six basic groups: limited education or mismatched skills,

health and disability, criminal justice system involvement, caregiving and family responsibilities, limited

economic and social resources, and demographic and other individual characteristics (including

immigration status), especially as they interact with systemic racial discrimination.

107

These

characteristics and how they may manifest as barriers to employment

108

are briefly outlined in Figure 3.

Although many think of the Social Security Act of 1935 as the dawn of “welfare” in the United States,

federal social assistance began with the mother’s pension (the predecessor to Aid to Dependent

Children, or ADC, later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children, or AFDC).

91,92

At first,

primarily white women primarily accessed mother’s pensions. During this time, policymakers

designed the programs to allow mothers to meet their basic needs without working outside of the

home. Only once more African American women began to participate, were work requirements

implemented.

93, 94

The programs also attempted to restrict women of color’s access to basic needs

assistance. In the 1930s, when there was unmet demand for domestic work and for labor during the

harvesting seasons, local administrators of the Federal Emergency Relief program often seized the

opportunity to deem Latina and black mothers “employable” under the “employable mother” rule—

forcing them to work outside of the home to receive benefits.

95

Relief programs thus “had the dual

function of keeping white mothers at home and forcing Latinas and blacks into the low-wage labor

market.”

96

States also enforced “employable mother” rules in ADC.

97

Place has also played a role in the history of racial discrimination and work requirements. In 1910,

most African American people lived in the South.

98

Between 1915 and 1970, over 6 million African

American people fled the south to escape economic exploitation, extremely limited economic

opportunities, and pervasive racial terrorism (such as public lynching and mob violence) in the hope

of a better life—a period now known as the “Great Migration.”

99, 100

As more African Americans

flowed north, northern states began to adopt some of the work requirements already prevalent in

relief programs in the South.

101

Equally salient have been the harmful race-based narratives generally surrounding people

experiencing poverty, particularly harming people of color. In many cases, these narratives were

employed to appeal to working-class whites and garner support for policies to reduce human

services spending.

102, 103

These false narratives ignore the realities of the labor market discrimination

and exclusion people of color face, in particular—and the fact that most people who receive public

benefits who can work, do so.

Policy that is not conscious of racial inequities can exacerbate racial injustice. Recently, a 2018

Michigan bill proposed requiring proof of working 30 hours per week in order to access Medicaid—

unless the individual lived in a county with an unemployment rate over 8.5 percent.

104

At face value,

exempting people in high-unemployment areas from work requirements seems practical and fair. In

reality, however, the areas that would have qualified were largely populated by rural whites.

105

In

contrast, residents of majority-black Detroit and Flint would not have been exempt because,

although both cities had qualifying unemployment rates, the larger counties did not. As a result, the

exemption would have largely excluded African Americans in cities.

106

Conditioning Access to Programs that Ensure a Basic Foundation for Families on Work Requirements | 24

Figure 3. Selection of barriers to employment unaddressed by work rules

Source: Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, 2019

Limited Education, Experience, & Skills

Limited educational attainment (having less than a high school degree or equivalent) may be one of the

most prevalent barriers to employment among low-paid workers.

109

People without a high school

degree or equivalent often cannot access programs developing the training necessary to attain technical

skills, credentials, and normative professional skills.

110

Not having enough formal, recent, or relevant

work experience may also make it difficult for workers to re-connect or stay connected to the labor

force. Workers may also experience significant barriers to getting new skills. For example, access to

school and training may be limited because of barriers such as a lack of available and affordable

transportation,

111

child care,

112

and other prohibitive costs.

113

Older workers may lack access to training

for new technology used in their industries, as well.

114

Limited Economic & Social Resources, Including Place-Based Barriers

Material hardship and economic insecurity makes obtaining or maintaining employment more

challenging. Other factors, such as geography and social network limitations, can also make it more

BARRIER TYPE

POPULATION WITH BARRIER

Limitations in Workers’ Overall

Productivity

Human

Capital

Limited Skills & Education

Immigration Status: Recent Immigrant, Especially

Refugee/Asylum Seeker

Personal

&

Logistical

Limited Economic & Social Resources: Transportation,

Housing, Stability, etc.

Caregiving & Other Family Responsibilities

Health & Disability: Work-limiting Physical, Mental, or

Sensory Health Condition or Disability

Systemic Discrimination by

Employers

Legal

Immigration Status: Undocumented Status

Criminal Justice System Involvement

Demographic

Apparent Health Condition or Disability

Age

Race, Ethnicity, & Origin

Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity (SOGI)

Working Paper

Unworkable & Unwise | 25

difficult for people to work. For example, housing-related instability due to limited economic

resources—such as the loss or threat of losing housing assistance, frequent moves, and experiencing

homelessness—can have extraordinarily negative impacts on one’s ability to remain attached to the

labor force,

115

particularly for people with disabilities.

116

Moving also can exacerbate transportation

issues for lower-income workers, compounding barriers to job searching

117

and work.

118

,

119

Groups likely

to face transportation barriers include individuals living in rural areas,

120

individuals with disabilities,

121

and low-income individuals. At-home internet access is also increasingly important for workers and

jobseekers to be successful in the labor market (and for complying with work reporting

requirements),

122

and yet, among current Medicaid enrollees in the U.S., more than a quarter “do not

use the internet.”

123

Even if one’s housing situation is stable, place-based factors (such as geography and

social network limitations), can create obstacles to employment for many. For example, jobseekers

living in areas where there are limited job opportunities, including rural areas

124

and on American

Indians and Alaska Natives (AIAN) tribal lands,

125

may find it difficult to obtain employment.

Caregiving & Other Family Responsibilities

Caregiving and family responsibilities, in the absence of adequate work-family supports and policies, can

also impact one’s ability to participate in the formal labor force.

126

,

127

In Georgia, one of the states

contemplating Medicaid work requirements,

128

over one-quarter of Georgia parents with children under

age 5 “reported that, in the past year, they or someone in their family experienced a significant

disruption to employment—quitting, not taking, or greatly changing a job—due to challenges with child

care.”

129

The same study estimates that annually, child care-related challenges for parents cost the state

at least $1.75 billion “in lost economic activity” (such as through adverse employment-related

outcomes).

130

Additionally, among all working-age Medicaid participants in the U.S. who are not

working,

131

nearly one-third (28 percent) cited caregiving or other home responsibilities as preventing

them from working.

132

Health & Disability

Work-limiting physical, mental, or sensory health conditions and disabilities present barriers to

employment for many.

133

This may be due to limits to capacity for work, both real and those perceived

by others.

134

About 1 in 5 childless adults enrolled in SNAP in 2014 who did not have income from a

disability program reported either a disability that prevents or limits the type of work they can do such

as hearing, walking or climbing stairs, or concentrating and making decisions due to a physical, mental,

or emotional condition.