Process and Public Engagement Plan

for Active Transportation/FUTS Master Plans

with the City of Flagstaff

By

Emily Melhorn

A Practicum Report

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master of Science

In Applied Geospatial Sciences

Northern Arizona University

Department of Geography, Planning and Recreation

December 2019

Approved by

Alan Lew, Ph.D., AICP, Committee Chair

Dawn Hawley, Ph.D.

Martin Ince, Multi-Modal Transportation Planner, City of Flagstaff

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 1

Abstract

The City of Flagstaff will continue to experience an increase in population growth for multiple

reasons, including high quality of life, student population growth, and retirees migrating on a

more permanent basis to Flagstaff for its cooler temperatures. The City of Flagstaff also

experiences a year-round short-term population increase as a result of tourist attractions in

Flagstaff and surrounding areas. These patterns have led to increased traffic congestion. The

City of Flagstaff’s Active Transportation/FUTS Master Plans’ goals are to shift current and

growing population’s transportation modes from single-occupancy vehicles to increased

walking and biking that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve air quality, and meet other

stated goals of the Flagstaff Regional Plan: 2030 Place Matters (City of Flagstaff, Comprehensive

Planning, 2014). Public engagement is essential to a vibrant active transportation planning

process. Public engagement in a traditional top-down planning process helps to inform

priorities for infrastructure and improve the physical barriers for walking and biking. Public

participation that seeks to engage the community from a grass-roots approach helps to

understand the cultural barriers to walking and biking, as well what motivates residents to

switch from a vehicle-dominated mode of transportation. The City of Flagstaff public

engagement plan chose to reach the community in both top-down and grass-roots approaches.

During the period of June through December 2017, the City of Flagstaff public engagement plan

conducted surveys, held events and summits, utilized social media and infographic techniques,

and worked with other community groups to promote a culture of and increase walking and

biking in Flagstaff.

Keywords: public participation, engagement, place-making, place making, active

transportation, walking, biking, transit

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 2

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 3

Table of Contents

Abstract ..........................................................................................................................................1

Letter of Significant Contribution .................................................................................................. 2

Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 5

Background and Purpose..............................................................................................................11

Objectives .................................................................................................................................. 11

Justification ..................................................................................................................................12

Policy Review ...............................................................................................................................12

Benefits of Active Transportation ............................................................................................... 14

Environmental Benefits.................................................................................................................15

Health Benefits ............................................................................................................................ 17

Economic Benefits ....................................................................................................................... 19

Equity Benefits ............................................................................................................................ 22

Quality of Life Benefits ................................................................................................................ 25

Other Information in Peer City Master Plans .............................................................................. 27

Design and Implementation .........................................................................................................28

Communication Tools ................................................................................................................. 29

Community Surveys .................................................................................................................... 31

Walking-Biking-Trail Summits ..................................................................................................... 32

Tabling Events ............................................................................................................................. 34

Flagstaff Walks!.............................................................................................................................35

PAC/BAC Meetings ...................................................................................................................... 35

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 4

Stakeholder Interviews ............................................................................................................... 36

Results and Discussion ................................................................................................................ 36

Further Outreach Recommendations ......................................................................................... 37

Further Infrastructure Recommendations .................................................................................. 40

Further Surveying Recommendations…………………....................................................................... 42

Flagstaff Walks! Events Reflection .............................................................................................. 43

Making the Case Reflection ......................................................................................................... 44

Active Transportation Summits Reflection ................................................................................. 46

Reflection on Equity ................................................................................................................... 49

Funding Active Transportation Reflection .................................................................................. 51

Works Cited ..................................................................................................................................54

Appendix A: Public Participation Draft ....................................................................................... 59

Appendix B: Draft Goals and Strategy Surveys ........................................................................... 67

Appendix C: Facilities Voting Map Results .................................................................................. 71

Appendix D: Stakeholders ........................................................................................................... 74

Appendix E: Stakeholder Survey ................................................................................................. 77

Figures and Tables

Figure 1: Cover of City of Flagstaff Bike Plan 1980 ........................................................................8

Figure 2: Cover of City of Flagstaff Bicycle Plan 1991 ................................................................... 8

Figure 3: Flagstaff Transect Zones .................................................................................................9

Table 1: Matrix of Master Plans................................................................................................... 13

Figure 4: Four Types of Cyclists.................................................................................................... 16

Figure 5: Health and Economic Infographic ................................................................................ 17

Figure 6: Facebook Post Health Benefits .................................................................................... 18

Figure 7: Facebook Post Economic Benefits ................................................................................20

Figure 8: FUT Facebook Cover Image ......................................................................................... 21

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 5

Figure 9: Facebook Post Economic Benefits ...............................................................................21

Figure 10: Facebook Post for Small Business Saturday ............................................................... 22

Figure 11: Image on Equity Issues .............................................................................................. 23

Figure 12: Facebook post on Equity Issues ................................................................................ 24

Figure 13: Image on Quality of Life Issues ................................................................................. 25

Figure 14: Facebook post on Quality of Life Issues .................................................................... 26

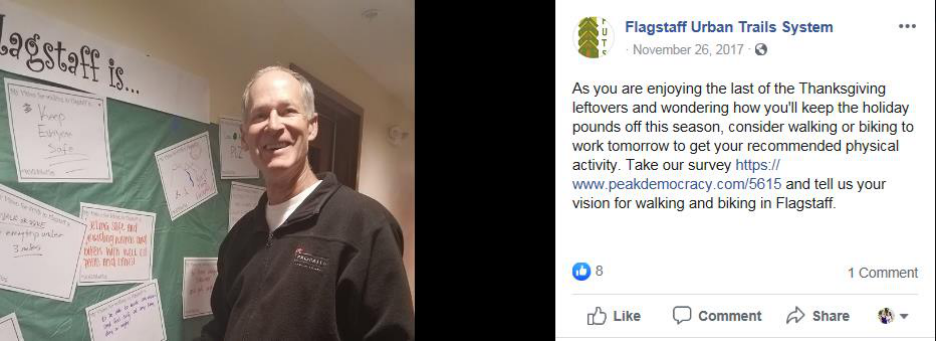

Figure 15: Facebook post on HOH meeting …............................................................................. 29

Figure 16: Facebook post on Black Friday ……............................................................................. 30

Figure 17: Infographic on FUTS trails user survey results ……..................................................... 31

Figure 18: Goals and Strategies Results ……................................................................................ 32

Figure 19: Flyer for November 1

st

Summit ……............................................................................ 32

Figure 20: Flyer for November 15th Summit ……......................................................................... 32

Figure 21: Results Map of Public Priority of Crossings …….......................................................... 33

Figure 22: Dot Voting System ……................................................................................................ 33

Figure 23: Photo of Vision Board ……........................................................................................... 33

Figure 24: Photo of Tabling Event ……......................................................................................... 34

Figure 25: Poster of Flagstaff Walks! Events ……......................................................................... 34

Figure 26: Facebook post about Public Art Events ……................................................................ 35

Figure 27: Meet Me Downtown inaugural flyer ….……................................................................ 43

Figure 28: Facebook post with walking quote by Edward Abbey ….……...................................... 44

Figure 29: Facebook post with biking quote by Anon ……………….….……...................................... 45

Figure 30: Photo from November 1

st

Summit …………………………..….……...................................... 48

Figure 31: Flagstaff Citizens’ Transportation Tax Commission flyer ……………………………………..… 50

Figure 32: F3 Position on Proposition 419 …………………………………….……………………………………..… 51

Figure 33: Proposition 419 Logo …………….…………………………………….……………………………………..… 52

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 6

Introduction

Flagstaff, Arizona is the largest city in Northern Arizona and has within this last decade

seen increased traffic congestion. Flagstaff is the site of one of three universities in the state,

Northern Arizona University (NAU). Flagstaff has city, county, and regional offices for the area

that employ thousands of people. It is home to many scientific research facilities including

Lowell Observatory, The U.S. Naval Observatory, and The United States Geological Survey

(USGS) Flagstaff Station. It also serves as a regional hub for manufacturing like Joy Cone, Purina,

and W.L. Gore. Flagstaff’s estimated population as of 2017 is 69,903 (U.S. Census Bureau,

Population Division, 2017). From 2010 to 2017, the City of Flagstaff’s population grew by 9%

(U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, 2017).

There is also a seasonal nature to living in Flagstaff for many community members,

which is not entirely represented in official census counts that help influence transportation

decisions. NAU’s current student population in Flagstaff is 22,791 (Arizona Board of Regents,

2019). This decade from 2010, NAU’s Flagstaff enrollment increased 23% (Northern Arizona

University, 2018). While students live and spend the vast majority of their time in Flagstaff, for

emotional and financial reasons, or just a general lack of awareness, they might be counted by

the census in their hometowns (Cohn, 2010).

Flagstaff also has a seasonal population of vacation home owners; most who buy these

homes to reside in Flagstaff in the summer months for its cooler temperatures than many other

parts of Arizona and the Southwest. Flagstaff’s closest major metropolitan cities of Las Vegas,

Phoenix, and Tucson are the fastest increasing temperature cities in the nation (Climate

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 7

Central, 2019). As these warming trends continue, the “summer” home in Flagstaff is

increasingly used as the primary residence for a large portion of spring and fall as well.

And lastly, Flagstaff has five and half million year-round visitors coming to the area to

experience its outdoor and cultural attractions, the Arizona Snowbowl, historic Route 66, as

well as using Flagstaff as a base to visit nearby Grand Canyon National Park, Sedona and Oak

Creek Canyon, and other Northern Arizona attractions. In a three-year period from 2014-2015

until 2017-2018, Flagstaff saw its visitation grow 27% (Flagstaff Convention and Visitors Bureau,

2018). With these many different types of growth: general population growth, increased

student enrollment, seasonal residents staying longer, and more tourism have all led to a

remarked increase in traffic congestion on both major and minor corridors in Flagstaff. In

addition to more traffic congestion, it also means increased difficulties in finding parking

spaces. These car-related aggravations and costs associated with more idling and parking have

led to the perception of decreased quality of life for those Flagstaff residents still firmly

committed to traveling by automobile for all their transportation needs.

There are many reasons why U.S. urban planners in the 21st century have placed

greater emphasis on active transportation planning, which includes walking, biking, and transit.

Active transportation can mitigate the obesity epidemic, reduce pollution and impacts of

climate change, creates greater equity among citizens’ transportation options as income

disparity increases, spurs economic development, is more cost-effective than automobile-

based planning, and fosters more human-scale place-making, which strengthens community

ties and reduces road-rage and neighborhood criminal activity.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 8

Figure 2: Cover of City of Flagstaff 1991 Bicycle Plan

The City of Flagstaff has shown its support of active

transportation in various ways since the 1980s. Flagstaff

created its first Bike Plan in 1980 and updated it in 1991

(City of Flagstaff, 1980, 1991). The original Flagstaff Urban

Trails System (FUTS) started as a proposed 3.2-mile plan

recommended by an ad hoc committee (City of Flagstaff,

1988). The Flagstaff Metropolitan Planning Organization

(FMPO) was created in September 1996 after Flagstaff

reached the required 50,000 people. The FMPO was

forward-thinking by hiring a Multi-Modal planner to be

inclusive of all transportation needs. The FMPO included

active transportation needs like bike lanes, more FUTS

trails, and completed sidewalks in the proposed projects

for the first-ever transportation tax passed by Flagstaff

residents in 2000. The “Transportation Decision 2000” 20-

year transportation tax helped expand the FUTS trail

system from 22 miles to over 50 miles (FMPO, 2017).

The City of Flagstaff has also supported active transportation through zoning changes. In

2011, the Flagstaff City Council adopted a revised Zoning Code with form-based districts to

promote transit- and pedestrian-oriented infill redevelopment (Forms-Based Code Institute,

2017). In new developments, the Comprehensive Planning for the City of Flagstaff is

Figure 1: Cover of City of Flagstaff 1980 Bike Plan

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 9

incentivizing reduced parking

spaces in exchange for free bus

passes for residents, more bike

parking, and other such measures

to help promote an active

transportation lifestyle.

However, despite Flagstaff’s

measures to foster more walking

and biking, there are many barriers to making active transportation the primary form of

transportation in this and many other communities. Some of the barriers are physical; the

infrastructure of a community may not support walking, biking, and public transit that is safe

and convenient. Insufficient infrastructure could be a lack of sidewalks, separated crossings,

bike lanes and paths, bike parking, lighting at night, places to sit to wait for the bus, adequate

shelter from weather, timely snow and ice removal, frequent and consistent bus routes along

major and minor corridors, or even a lack of density and mixed-use neighborhood amenities

that facilitate active transportation. Another physical barrier that hinders active transportation

is automobile-dominated infrastructure that makes driving easier through free parking, wide

roads, turning lanes, high speed limits, traffic lights oriented towards automobiles, as well as

low-density Euclidian zoning that encourages driving.

Other barriers to active transportation are cultural: parents who don’t want their

children walking or biking to school for fear of kidnapping, people who associate active

Figure 3: Flagstaff Transect Zones

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 10

transportation with poverty, businesses that do not offer flexible start-times or changing

facilities for employees wishing to use active transportation, physical abilities, weather-related

hurdles like rain, snow, and hot weather, and a rushed culture which sees the automobile as

one of the enduring symbols of American freedom.

For many of these barriers, active transportation planners have taken a top-down

approach to creating better infrastructure that facilitates walking, biking, and public transit. It is

a mentality that states, “If we build it, they will come” (or walk, bike, and take public transit).

Public participation and community input can be viewed as a mandatory obligation, a box to be

checked in the planning process. While this approach may improve the physical barriers and

infrastructure, it rarely addresses the cultural barriers or appropriately prioritizes the needs of

the entire community, including those who could be motivated to walk and bike more if proper

incentives are in place. This applied practicum research asks whether active transportation

planning that also embraces a grass-roots approach to community outreach and input will

increase rates of walking, biking, and public transit, as well as strengthen the community’s

commitment to active transportation infrastructure and strategic partnerships that will make

active transportation more safe and convenient. From the time since this applied practicum

research, I also realized the importance of having a funding source in place to address physical

infrastructure barriers and educational programs for cultural barriers. The public participation

outreach should have emphasized getting more active transportation enthusiasts on the

transportation tax commission that determined funding priorities for all forms of transportation

from 2020 to 2040. The sales tax for transportation heavily favors roads and leaves $101 million

unfunded for active transportation out of the $130 million needed to implement the Active

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 11

Transportation Master Plan. Getting input from the community is important, but holds less

significance if there is no means to fund that community vision.

Background and Purpose

This applied research practicum is focused on increasing walking and biking in Flagstaff

through a public engagement plan that emphasizes grass-roots place-making as a means to

engage the community. Previous iterations of the public engagement plan relied almost

exclusively on traditional top-down approaches to collecting public input, such as surveys and

lecture-style open houses where priority was communicating plans to the already-converted

public. While this top-down approach is still important to receive input from the public who

already regularly walk and bike as a primary mode of transportation, this applied research

practicum’s purpose was also to engage the public who might be interested in active

transportation, but have not yet embraced it for a variety of physical and cultural barriers.

Objectives

Public participation policies for the City of Flagstaff were adopted in 2012 through

Resolution 2012-39, which established the goals of clarity, transparency, and two-way

communication in the public participation process. These objectives consisted of five levels of

public engagement (City of Flagstaff, Flagstaff Metropolitan Planning Organization, 2019):

● Inform to provide the public with balanced and objective information to assist them in

understanding the problems, alternatives and/or solutions

● Consult to obtain public feedback on analysis, alternatives and/or decisions

● Involve to work directly with the public throughout the process to ensure that public

issues and concerns are consistently understood and considered.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 12

● Collaborate to partner with the public in each aspect of the decision including the

development of alternatives and the identification of the preferred solution

● Empower to place final decision-making in the hands of the public.

Justification

As traffic congestion has the potential to increase dramatically through both population

growth and increased tourism activities, Flagstaff has the opportunity to reduce congestion and

its negative impacts, including air quality, greenhouse gas emissions, and reduced physical and

mental well-being from sitting in traffic, by building the infrastructure for a more walking and

biking friendly environment. Through events, education outreach, and collaboration with

community groups, the benefits of active transportation can be more easily realized to the

public as infrastructure improves.

Policy Review

The literature review for this applied practicum research includes the active

transportation master plans of peer communities that have greater rates of participation than

Flagstaff, as well as a few communities that are well-known for their biking and walking culture.

Some of the cities separate their pedestrian and biking into two plans, and I reviewed both for

ideas, programs, and strategies that might improve the walking and biking culture in Flagstaff.

From these plans, I also further researched their source data to find additional information or

confirm accuracy. The table on the following page shows the different plans reviewed and key

points used during the internship.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 13

Table 1: Matrix of Master Plans reviewed during internship

Master Plan Year Bike/Ped Key points used in internship

City of Fort Collins Pedestrian

Plan

2011 Pedestrian

Used health information and

environmental statistics from plan

City of Fort Collins Bicycle Master

Plan

2014 Bicyle

Used health statistics, safety in

numbers statistics, parking costs,

stakeholder meeting with church group

Eugene Pedestrian and Bicycle

Master Plan

2012 Both

used definition of active transportation

Philadelphia Pedestrian and

Bicycle Plan

2012 Both

Greenplan open space program

City of San Diego Bicycle Master

Plan

2013 Bicyle

used mental health information, costs

of bike vs. car, tourism

Pima Association of Governments

Regional Pedestrian Plan

2014 Pedestrian

visual graphics were repurposed

Tucson Regional Plan for Bicycling 2009 Bicyle

reviewed as example of master plan

with no benefits section

Bellingham Bicycle Master Plan 2014 Bicyle recruiting businesses information

Bellingham Pedestrian Master

Plan

2012 Pedestrian

quality of life information

City of Davis Bicycle Action Plan 2014 Bicycle history section and structure of plan

City of Santa Cruz Active

Transportation Plan

2017 Both

title name, 4 different types of riders

City of Boulder Transportation

Master Plan

2014 Both

5 "E's" sections, visual graphics

City of Boulder Transportation

Master Plan Action Plan

2014 Both

example of short summary of plan

City of San Luis Obispo Bicycle

Transportation Plan

2013 Bicyle

used summits as template, car costs,

plan itself difficult to read visually and

too much history

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 14

Benefits of Active Transportation

In reviewing these master plans, my research also involved compiling and analyzing how

peer cities communicated the benefits of walking and biking. The benefits of walking and biking

are an integral part of implementing short and long-term planning for bike and pedestrian

infrastructure. With the realities of limited funding within municipalities, the case must be

made for why these projects and infrastructure warrant priority in the goals of the city.

These benefits can also be used in public engagement through social media, websites, and at

various events to make the case for why the public would benefit from walking and biking

more. Through the literature review research of the peer city master plans, the following

Activate Missoula 2045: Bicycle

Facilities Master Plan

2017 Bicyle

safety in numbers and environmental

information, benefits table

Laramie County Comprehensive

Plan

2016 Neither

no active transportation master plan,

not fantastic infrastructure, but their

rates higher than Flagstaff

Chico Urban Area Bicycle Plan 2012 Bicyle

reviewed as example of master plan

with no benefits section

Logan City Bicycle and Pedestrian

Master Plan

2015 Both

had very different benefits categories:

safety, winter air quality, college

campus

Bend Metropolitan Planning

Organization: 2040 Metropolitan

Transportation Plan

2014 Both

one mile walk, three mile bike data, air

quality information

Benton County Transportation

System Plan: Bicycle and

Pedestrian Plan

2001 Both

used economic statistics

Bike Buzz: All Users: Bicycling in

Pocatello and Chubbuk

2012 Bicyle

used health statistics

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 15

categories of benefits consistently were listed: Health Benefits, Environmental Benefits, Equity

Benefits, Economic Benefits, and Quality of Life Benefits.

Environmental Benefits

The environmental benefits of walking and biking can greatly contribute to reduced

greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to help mitigate the impacts of climate change and improve

air quality in a community. Transportation that uses fossil fuels account for the largest source of

many GHG emissions in the country, with the City of Davis (2014) contributing 57% of its GHG

emissions from transportation (City of Davis, p.12). The Fort Collins Pedestrian Plan (2011)

states that transportation is responsible for nearly 80% of carbon monoxide and 50% of

nitrogen oxide emissions in the United States (Fort Collins, p. 16). While many scientific

communities, health organizations, and government agencies, including the United Nations

(2019), agree that climate change is the greatest systemic threat to humankind, I chose not to

highlight the benefits of reducing this risk in the “Making the Case for Walking and Biking”

paper or through social media, websites, and at public outreach events.

My decision not to emphasize the environmental benefits was for several reasons.

According to American Psychological Association data from 2018, 29% of people in the United

States still are not certain that climate change is happening or is primarily human-caused. Half

of the population doesn’t think they will personally be harmed by climate change, and only five

percent think we are capable of reducing global warming (Winerman, p. 80). Denial,

uncertainty, lack of perceived immediacy, and an overall sense of futility are the narratives that

dominate Americans’ thoughts and conversations about climate change.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 16

A strategy to highlight the environmental benefits of active transportation might

provide hope and motivation to a small percentage of the Flagstaff community to walk and bike

more, particularly on a cold, busy, or otherwise inconvenient day. However, this

communication mostly would serve as a reminder to the group identified as “Enthused and

Confident” by the City of Santa Cruz Active Transportation Master Plan (2017, p 23).

This group already feels comfortable biking in most scenarios and make up no more

than 10% of a community’s population (City of Santa Cruz, 2017). To reach the not-yet-

converted, the “Interested but Concerned” that make up about 60% of a population (City of

Figure 4: Four Types of Cyclists. (2009). Roger Geller, City of Portland Bureau of Transportation

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 17

Santa Cruz, p. 23), the most effective encouragement would be the two benefits that

affect the largest portion of the population: health and economic benefits.

Health Benefits

The United States spent 3.65 trillion in health care costs in 2018 (Sherman), which was

18% of the total U.S. GDP (Bureau of Economic Analysis). Americans spent another 28.6 billion

on gym memberships (Galina, 2019), 3.86 billion on home fitness equipment (Statista 2018),

and 36.7 billion in dietary supplements in 2015 (Austin et al., 2017). And these figures do not

include the entire picture of what Americans are willing to spend in pursuit of better health.

Health and healthcare are big business in the United States. It is also the issue that is

most concerning to Americans, where 55%

say that they worry a great deal about

healthcare, more than other issues like the

economy, Social Security, the environment,

or federal spending (Norman, 2019). Active

transportation can help alleviate

healthcare costs and help make people

healthier through increasing physical activity, which has a significant influence on obesity rates

and chronic health issues.

While Coconino County’s rates of obesity (25%) are lower than the national average of

36.5%, Flagstaff currently benefits from short commute times of 15.9 minutes (Coconino Public

Health, 2016). This provides us with less sedentary time in the car, but also gives us more time

Figure 5: Infographic created to demonstrate health benefits of active

transportation

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 18

to take advantage of the outdoor recreational opportunities in the area to lead an active

lifestyle. However, as our vehicle commuting times increase, we will see a 1% increase in

obesity for every additional 10 minutes spent in the car (Lawrence et. al, 2004).

Walking and biking for transportation is an easy, convenient, and cost-effective way to

incorporate the recommended 30 minutes (60 minutes for children) of physical activity into

busy schedules. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services also lists walking and biking

commuting as the safest way to get recommended physical activity (2008, p.36).

Figure 6: Facebook post discussing health benefits of walking and biking

Health problems related to physical inactivity result in increased medical costs for

families, the private sector, and the government. Quality Bike Products Health and Wellbeing

Program demonstrated in 2012 that bike commuters had $167.77 fewer medical claims per

year (64% less) than their car-commuting coworkers (Quality Bikes, p. 2). While there are

multiple factors that have contributed to the obesity epidemic in the United States, including

diets with more processed foods and larger portions, a sedentary lifestyle is a significant

contributor that can be reduced through active transportation.

Safety is a big issue for many of the “Interested but Concerned” 60% of the population

who could be compelled to embrace active transportation. And even though the U.S.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 19

Department of Health and Human Services listed active transportation as the safest form of

getting physical activity (less injuries overall), the perception of dangerous crashes with

automobiles needs to be addressed with a wary population, as these are more likely to cause

serious injury or fatality.

While more vehicles on a road lead to more vehicle crashes, the inverse is true for

pedestrians and bicyclists. Motorists normalize the presence of larger numbers of pedestrians

and bicyclists. Incorporating comfortable facilities for walking and biking can help reduce

crashes and make roadways safer for all users, including motorists. According to a Working for

Cycling 2007 study, doubling walkers and bikers on the streets leads to 34% fewer motor-

pedestrian crashes. Drivers have a greater awareness of bicyclists and pedestrians in larger

numbers and more bicyclists and pedestrians can advocate for safer, more comfortable

facilities. Promoting the health benefits, while adequately addressing safety concerns through

both education and infrastructure improvement can help incentivize larger portions of the

population to make the switch to active transportation.

Economic Benefits

When considering the economics of active transportation, three areas consistently

stood out for their benefits: money that people saved by utilizing active transportation, money

that municipalities saved by prioritizing active transportation over cars, and how the overall

local economy benefitted from a walking and biking friendly environment.

The money that people could save by utilizing more active transportation seemed particularly

important to Flagstaff residents. According to the 2015 Flagstaff census, 25.7% of Flagstaff are

at the poverty level and 42% pay more than a third of their income on housing. The San Luis

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 20

Figure 7 Facebook post on economic benefits

Obispo Bicycle Plan stated that

vehicle and transportation costs

are typically the second largest

expense, around 8-10% of the

household budget (2013, p.14).

In order to make financially

supporting active transportation

more appealing to the Flagstaff

population who otherwise want

smaller government, FMPO

communicated that active

transportation infrastructure is

both cheaper than road

maintenance, but also has an

added benefit of creating more

jobs.

Portland’s 350 miles of

bikeways cost $60 million to build. This is the same estimated cost of one mile of urban freeway

(Bicycles in Portland, 2016). Bikeways require much less pavement and maintenance costs than

roads geared toward automobiles. Not only do bike lanes and sidewalks cost less in materials

and maintenance than roads, but they also create more construction jobs, which cycles that

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 21

Figure 8: Facebook cover image November-December 2017

Figure 9: Facebook post on economic benefits

money back into the community. For every $1 million spent on roads, it creates 7.8 jobs. For

the same amount of money, bike lanes create 11.4 jobs, sidewalks create 10 jobs, and multi-use

(like the FUTS trails) creates 9.6 jobs (Garrett-Peltier, 2011).

Walking and biking transportation

add money to an economy,

particularly for local, small

businesses that are more likely to

be in pedestrian-friendly areas. For

every $100 spent at a local

business, $68 stays within the local

economy, compared to $30 with

national chains whose

infrastructure is typically not

conducive to walking and biking

(Massachusetts Government,

2013). Walking and biking can also

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 22

Figure 10: Facebook post that tied Small Business Saturday to active transportation

be tourism activities in their own

right. Bicycling generates more

than $100 billion a year to the U.S.

economy. It supports nearly 1.1

million jobs and generates nearly

$20 billion in federal, state, and

local tax revenues, as well as

billions spent on meals,

transportation, lodging, gifts and

entertainment during bike trips

and tours (Flusche, 2012).

According to an Urban Land Institute Study in 2016, over half of working-age people are

choosing walkability as the top or high priority in where to live, businesses who want to hire

skilled employees are also looking at walkability in where to locate their next office branch. In

the last five years, businesses that have registered as “Bicycle Friendly Businesses” has more

than tripled, including many Fortune 500 companies offering high-paying careers (League of

American Bicyclists, 2017).

With monetary savings for residents and for government, as well as attracting new

employment and keeping more money circulating in the local economy, the economic benefits

of active transportation offer a compelling case to prioritize its funding even among skeptical

crowds.

Equity Benefits

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 23

The FMPO has an active interest in equity

issues and how to make active transportation

more accessible to Flagstaff’s vulnerable

populations. The challenge in public

communications is to speak about equity in a

manner that also feels relevant to the entire

community.

Although it is estimated nationwide

that 30% of the population cannot drive, Flagstaff has a similar mix of people who are not old

enough to drive, have a possible reduced capacity to drive, or do not have access to a car.

According to the 2015 Census, 23.8% of the population of Flagstaff are under 15 or over 65,

who might have reduced vision and other functions that might hinder driving abilities. Also

3.5% reported having no access to a car. There is not census data on people who never learned

to drive. These groups would benefit from active transportation.

According to a Smart Growth America study, non-driving seniors make 65% fewer trips

to visit family and friends or to church; many report they do not like to ask for rides, particularly

for social, “non-essential” trips. More than half of older adults would walk, bike, or take public

transit more if there are adequate sidewalks, safer short crossings, and adequate, comfortable

seating when waiting at a bus stop (Smart Growth America, p 2). Increasing the comfort, ease,

and safety of walking, biking, and public transit will encourage seniors to be more active, social,

and engaged with the community, to receive adequate access to health care and social services,

and an overall increase in quality of life that can permit more seniors to age in their homes.

Figure 11: Image on equity issues

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 24

Figure 12: Facebook post on equity issues

Walking and biking to school has drastically decreased in the later part of the 20th

century, from 50% in 1969 to 15% in 2001. The distance to school remains relatively

unchanged, but perceptions of letting children walk to school (particularly unaccompanied)

have changed (Active Living Research, 2015). More parents are driving their kids to school as a

result, creating more congestion and stress as parents are also trying to get to work on time.

Parents think that they are doing what is best for their children by driving them. However,

children who walk or bike to school are better able to concentrate, perform better on cognitive

skills tests, and experience a

greater level of self-reliance

(Goodyear, 2013). There are also

fifteen charter schools in the

Flagstaff area that are changing

the landscape of how students can

feasibly get to school since their

enrollment is not location-based.

Creating infrastructure that fosters

safety, as well as education for

children on safe walking and biking

habits, like the Safe Schools

program, are good steps towards

increasing active transportation

rates. Although Mountainline has rerouted certain routes or even changed transit times to

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 25

Figure 13: Image of Quality of Life issues

accommodate some of the larger charter schools like Flagstaff Arts and Leadership Academy

and Basis, ridership by students remains low. A shift in cultural practices might also be

necessary to get walking and biking rates back to 50% for school age children.

There are many struggles both with infrastructure and on a cultural level to make active

transportation more appealing and accessible to seniors, children, and those at the poverty

level within the Flagstaff community. This is an area that the FMPO staff are dedicated to

improving and focusing on in the upcoming decades.

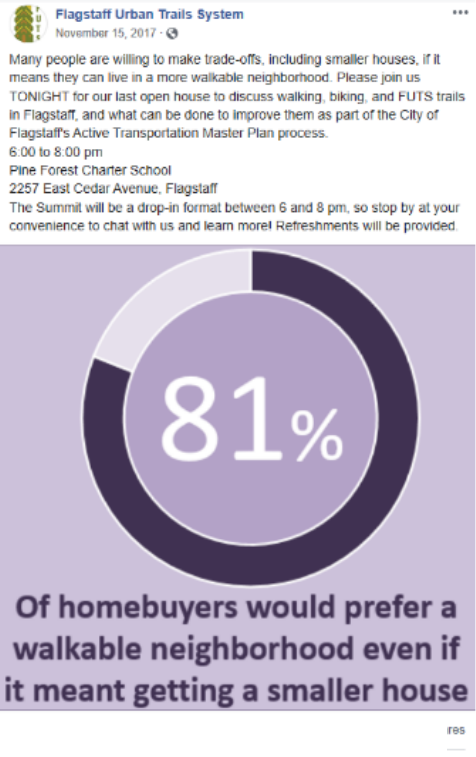

Quality of Life Benefits

Walkability and a bicycle-friendly environment are two

qualities that more people are generally starting to seek in the

places they choose to live. Only 8% of people wish to live in

neighborhoods where they need to drive all the time. The

common preference is walkability, whether that be in a small

town or urban center (APA, 2014). Residents want to become

more familiar and intimate with their community. Walkability heightens sense of community

through getting to know your neighbors, walkers, joggers, bikers, and trail users.

People are willing to pay for this preference, through either smaller or more expensive homes.

Homes that are close to trails and amenities in walking distance are valued between $4,000-

$34,000 more than homes with just average levels of walkability (Cortright, 2009).

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 26

This heightened sense of community also extends

to a reduction in criminal activity, which also is

another economic benefit as well as a quality of life

issue. Walking and biking promote activity on the

street, provide better opportunities to talk to and

get to know your neighbors, and create “eyes on

the street,” all of which help to discourage crime

and violence. Places that support compact, mixed-

use, walkable neighborhoods have lower crime

rates, particularly violent crimes (Browning et. al,

2010).

All five categories of benefits:

Environmental, Health, Economic, Equity, and

Quality of Life helped to frame how to

communicate with the public about active transportation and why it needs infrastructure and

program support. Through the review of the peer city master plans, I further researched their

source material to find new information about benefits. The peer city master plans also

provided ideas on where and how to collect data relevant to the Flagstaff community. These

categories of benefits helped determined which groups and organizations the FMPO could

build strategic partnerships with in Flagstaff to implement programs, as well as gather their

feedback through surveys and focus groups. The FMPO included organizations like Housing

Figure 14: Facebook post on Quality of life issues

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 27

Solutions and Northland Family Help Center along with more traditional allies like bike shops

and running groups.

Other Information in Peer City Master Plans

In the literature review of peer city master plans, I researched and evaluated the public

participation process for strategies to implement in Flagstaff. Some peer cities chose a lot of

public meetings and others utilized technology more to get input and spread the message. The

FMPO strove to do a mixture of in-person and technological outreach. San Luis Obispo had a

large percentage of attendees compared to population at their public meetings. These

meetings were called “bike summits” (2013, p. 68). The FMPO held two Active Transportation

Summits with a higher attendance than previous public meetings marketed as open houses.

For the Literature Review, I also researched within the master plans different options to

fund programs and infrastructure. I further investigated websites where noted in master plans

to see if Flagstaff qualified for any funds within these programs.

For the literature review, I also researched scholarly articles that discussed barriers to

why people do not walk and bike more. Why don’t more children walk and bike to school? Why

is our senior population more likely to ask family members for rides than walk to the store?

How does a single mother on assistance without a car feel about her transportation options?

The research has shown that the barriers could be incomplete infrastructure (missing sidewalks

and bike lanes), or poor design (long crosswalks), and sometimes it’s cultural (parents are

terrified their child will be kidnapped on their safe route to school). Not only does this research

indicate what kind of infrastructure and design might be effective in creating a more walking

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 28

and bike friendly environment, but it also demonstrates the educational messages and dialogue

needed with the community to increase walking and biking.

Through the peer city master plans, scholarly articles, and additional websites for

funding and program information, the scope of the problems and some solutions to increase

walking and biking in the City of Flagstaff were addressed for the scope of this practicum

project.

Design and Implementation

The methodology process for preparation and adoption of the Active Transportation

/FUTS Master Plans demonstrates how public engagement is incorporated into the overall

process. There are six process phases (City of Flagstaff, FMPO, 2019):

Phase 0 Previous work and engagement

Phase 1 Process introduction

Phase 2 Stakeholder engagement

Phase 3 Public review

Phase 4 Detailed review

Phase 5 Final approval

The majority of my applied research practicum occurred in Phase 0, but the resources

provided during the practicum are being implemented in all later phases.

Previous work and engagement includes foundational work for public engagement,

background research, and inventory and analysis of existing facilities. The background research

portion of this process phase provided a clearer understanding of the current conditions and

furnished a context to develop new master plans. Existing plans, policies, regulations, and

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 29

Figure 15: Facebook post on HOH meeting

guidelines were utilized in the background research, as well as creating reports of mode share

trends and peer cities analysis, reviewing national and state bicycle and pedestrian resources,

and reviewing pedestrian and bicycle crash data.

Inventories of facilities inventories were compiled and analyzed in detail for existing

pedestrian, bicycle, and trails infrastructure. These inventories included: a FUTS priority

evaluation, missing sidewalk inventory and prioritization, missing bike lane inventory and

prioritization, at-grade pedestrian and bicycle crossings, and grade-separated pedestrian and

bicycle crossings.

Public engagement efforts have

been conducted in a variety of activities

in support of the Active Transportation

and FUTS Master Plans. Some of the

activities include the following:

Communication Tools

Website- Active Transportation

Master Plan web page on the City of

Flagstaff website includes plans,

documents, timely information, and

opportunities for getting involved. The

website is located:

https://www.flagstaff.az.gov/3181/Acti

ve-Transportation-Master-Plan.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 30

Facebook – Flagstaff maintains a Facebook

page for the Flagstaff Urban Trails system (FUTS)

with over 2,000 members. The Facebook page is

located at: https://www.facebook.com/Flagstaff-

Urban-Trails-System-207094295408/. This page is

used to communicate information for the FUTS

system, as well as for walking, biking, and general

multimodal transportation. Infographics, and

photographs paired with statistical data were posted

on a daily basis to communicate the benefits of walking and biking to this large digital

population. FMPO regularly works with administrators of other Facebook pages, both inside

and outside of the City, to cross-post on items of mutual interest, as well as walking and biking

events in Flagstaff. In communicating the benefits of active transportation, FUTS Facebook

posts connected this information with events in Flagstaff. A notice of a High Occupancy Housing

(HOH) meeting was paired with information about youth preferences for active transportation.

Small Business Saturday was paired with information about how pedestrians and bicyclists are

more likely to shop at local stores (and spend more) along with a previous day’s post on

struggles of looking for parking on Black Friday. This strategy helped to provide relevance and

context about active transportation to issues and events already on people’s radar.

Notify Me- this webpage on the City’s website allows people to subscribe to email lists

to receive information from the City. The website is located at:

https://www.flagstaff.az.gov/list.aspx. The “Pedestrian-Bicycle-FUTS” list is sent information of

Figure 16: Facebook post on Black Friday

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 31

interest on the FUTS, walking, and bicycling. Subscribers

are also sent monthly meeting agendas for the City's

Pedestrian Advisory Committee (PAC) and Bicycle

Advisory Committee (BAC). This list has over 900

subscribers.

Flagstaff Community Forum- this is the online

forum for community surveys. The website is located at:

https://www.flagstaff.az.gov/3284/Flagstaff-Community-

Forum.

Story maps- Esri combine maps, narrative text,

images, charts and graphics, and other media in a single

interactive webpage to communicate information.

Community surveys

Have your say survey- was conducted in Spring

2017 with 125 responses. Four public surveys were

conducted for the Regional Transportation Plan, which

included significant results for walking and biking.

FUTS trail users survey – was conducted in

summer 2017 with 375 responses. The survey was

conducted to determine patterns of FUTS trail use and

users’ perceptions of the FUTS system. The survey updated a previous FUTS survey from 2011.

Figure 17: Infographic representation of FUTS trail

users survey results

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 32

Draft goals and strategies survey- was conducted in Fall 2017 with 167 responses. The

survey

gathered

feedback for

proposed goals

and strategies

to improve

walking and

biking in

Flagstaff. The

goals and strategies were developed for the Active Transportation Master Plan.

Walking-Biking-Trail Summit-Two summits were held on

November 1, 2017 at the Joe Montoya Center and November 15,

2017 at Pine Forest Charter School.

Approximately 100 residents

attended the two summits. The

summits were structured in a

drop-in open house format.

Community groups also tabled at the summits to promote

walking and biking activities in Flagstaff. Attendees were able to

participate in a variety of activities:

Figure 18: Infographic of results of Goals and Strategies Survey

Figure 19: Flyer for November 1

st

Summit

Figure 20: Flyer for November 15

th

Summit

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 33

Facilities voting maps-

Participants placed dots on six

large-scale maps depicting

existing and missing/planned

sidewalks, bike lanes, FUTS trails,

crossings, PedBike Ways, and the

bikeway network. Dots were

color-coded by priority.

Goals and strategies survey- A paper version of the online

survey was made available at the summits. The results were

included with the online survey

data analysis.

Strategies voting chart-

Draft goals and strategies were

printed on large posters; dots

were placed adjacent to

Figure 21: Results of Crossings Facilities Voting Map

Figure 22: Dot Voting System

Figure 23: Photo of Vision Board

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 34

strategies that participants consider most important or highest priority.

Vision board- Participants were invited to express their vision for walking or biking on a

sheet of paper, which was then attached to a wall with other vision statements.

Comment cards- Provided an opportunity to express any additional thoughts and

comments about the master plan and the summits.

Tabling events- FMPO and volunteers mostly from PAC/BAC have engaged with the

public at a variety of community events, including Earth

Day, Bike Bazaar/Bike to Work Week,

Arizona Trail Day, and Flagstaff

Community Market. These events include

maps showing existing and future FUTS

trails, sidewalks, bike lanes and crossings.

FUTS trail maps and other pedestrian and

bicycle literature was also distributed.

Public engagement included addressing

existing concerns with walking, biking,

and trails, the Active Transportation

Figure 24: Photo of tabling event

Figure 25: Poster of Flagstaff Walks! events

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 35

Master Plan, and the transportation tax renewal.

Flagstaff Walks!- This is a month-long series of events that are held yearly in September and

October, meant to engage with new portions of the public through fun activites. There are

several guided walks that start at the Flagstaff Community Market, including a Public Art Walk,

Southside Historic Walk, Geology Walk, Rio de Flag Walk, and Mural Walk. Events also included

a Progressive Breakfast, with community members conversing with FMPO staff and volunteers

at different coffee and breakfast places about walking and biking in Flagstaff. There are also

community clean-ups in parks and Safe Walk to School Day held in October. Promoting a

culture of walking and communicating with the public on walking benefits and infrastructure

hindrances are the goals of Flagstaff Walks!

PAC/BAC meetings- the Active Transportation Master Plan and FUTS Master Plan have been a

standing item on the agendas of the City’s PAC and BAC meetings. These meetings will continue

Figure 26: Facebook post for Public Art Walk

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 36

to serve as a public forum for the master plans. Both meetings are open to the public and can

be live-streamed from the City’s website.

Stakeholder interviews – will have 12 to 15 individuals representing city staff and community

groups. Interviews will include these questions:

What are the most critical actions we can take for walking, biking, and trails from among

the draft goals, strategies, and actions in the plans?

What should be the highest priorities for planned pedestrian, bicycle, and trail

infrastructure?

Have we missed anything in the plan?

How does walking, biking, and trails support the mission and work of your program or

agency?

A stakeholder survey will also be available online for a broader group of city staff and

community groups.

Results and Discussion

This results and discussion section has the perspective and advantage of time. It has

been almost two years since I finished my internship at the FMPO. In the year following my

internship, I found myself using the knowledge I had gained to advocate against the passage of

the transportation taxes on the 2018 City of Flagstaff ballot. The transportation taxes fund a

large portion of active transportation infrastructure. I am also much more familiar with the

tourism industry in this community working at the visitor’s center. This discussion section is

partially influenced by what happened after the internship was completed, what I might have

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 37

done differently, as well as items that were very much on my radar in the category of “if I had

more time” at the end of my internship.

Further Outreach Recommendations

Towards the end of my internship, I made a series of recommendations for future

outreach opportunities, ways to increase participation, and possible funding sources.

I recommended that the FMPO have public outreach meetings with Gore, Purina, Joy

Cone, NAU, Decker, and the other larger employers in Flagstaff. Punctuality is typically valued

by employers and the expectation is that employees arrive on the hour or half hour. However,

with a slightly more flexible start time that coincides with bus route times, active transportation

would be much more appealing to more employees. Bus pass incentives, changing rooms, and

possibly even showers could be planned within current buildings or future expansion. Seeing as

one parking space costs $7,500 to build and over $300 yearly to maintain (Victoria Transport

Policy, 2017), bus passes and changing facilities could be a cheaper alternative, as well as

attracting high-skill employees looking for active transportation options for their daily work

commute. Also discussing professional work clothes is important, especially for female

employees who might feel that they must wear dresses, skirts, and/or high heels to be

perceived as “professional.” These clothing items are not particularly conducive to active

transportation. Discussing ways to meet both professional appearance goals and active

transportation is possible. These issues could be agenda items at staff meetings or also be

incorporated in new employee training.

I discuss later the possible limitations of social walking events, but I think a Ciclivia for

Flagstaff could be an effective means to promote more walking, biking and bus transit in the

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 38

community. A few blocks of the downtown area could be closed to automobile traffic and

parking where people would be encouraged to bike or walk in the streets instead. Vendors, art

installations, and community organizations could rent the parking spaces for the course of the

event and bus transit could be free to the downtown area, with a rerouting of applicable bus

lines to accommodate the event. There are a few events that already close portions of streets

to traffic, but one event specifically devoted to “no cars” could make active transportation

seem more feasible to a larger number of the community. Partnering with the larger event

planners in Flagstaff, Downtown Business Alliance, bike shops, artist groups, and possibly the

Convention Bureau could make this a destination event for Flagstaff.

During the internship, I researched a lot of the various health benefits of active

transportation. Sharing this information to a wider audience by tabling at health fairs and other

events devoted to improved health could be an effective strategy to emphasize that people can

get the recommended physical activity per day through active transportation. This strategy can

alleviate people’s concerns that they need money for gym memberships or find more time in

the day to devote to “exercise,” but instead could be incorporated in the daily commute they

already do. As traffic congestion increases and parking becomes more difficult to find, the

difference in time between the automobile commute and active transportation is minimal, as is

already the case on the NAU campus during rush hours. Depending on the event, it could also

be an opportunity to reach more vulnerable populations of the community.

Now that the major Earth Day celebration for the City of Flagstaff is held in Bushmaster

Park, I recommend that the #2 bus line be free for the hours of the Earth Day event. The people

who attend Earth Day events are a captive audience for environmental issues and a free trip to

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 39

Bushmaster could foster more use overall of the transit system to reduce ghg. The grants that

help fund the free shuttles to Snowbowl during the week of Christmas, or have free service on

New Year’s Eve, could also help make the #2 bus line free for a couple of hours on Earth Day.

I also recommended expanding the Adopt-a-FUTS program to Friends of the FUTS or a

similar program. There is a waitlist for organizations who would like to adopt one of the FUTS

trails for clean-up days. The FMPO could recruit the waitlist to help at tabling, bicycle audits,

public meetings and help fill other volunteer needs of the FMPO. Having a sign that incidentally

helps promote the business or organization is likely a powerful motivator for many participants

of Adopt-a-FUTS. Figuring out comparable promotional opportunities for Friends of the FUTS

would be an important component to its success.

In my review of the Fort Collins Bicycle Plan (2014, p. 11) I thought it was interesting

that their active transportation team did a stakeholder meeting with a church. I recommended

outreach meetings to religious groups who have taken an outspoken position against climate

change and support environmental causes. Getting the support of religious leaders for active

transportation could be an effective, but very much overlooked means to get a large number of

community members walking and biking.

I recommended that the FMPO have outreach meetings with PTOs and neighborhood

associations to encourage more walking and biking of school age children. Whereas many of

the peer city master plans have emphasized safety issues and trainings, I actually think it’s more

important to emphasize the benefits to children of walking and biking, including exercise and

better classroom performance. An over-emphasis on safety I think just reinforces that walking

and biking to school is a dangerous activity. According to the National Center for Injury

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 40

Prevention and Control, the leading cause of death for children in the United States is

automobile accidents (2008). Establishing walk and bike trains in neighborhoods to school can

help normalize this activity and make more parents willing to join in the switch to active

transportation.

Basic bicycle maintenance courses and bike riding classes for people of all ages are also

an important part of increasing realistic transportation options. To create the infrastructure for

bicycle riding, but not the tools to ride or maintain them, is going to limit the people who can

adopt this form of transportation. Learning the skills of bike maintenance and riding,

particularly riding in inclement weather or at night with our dark sky ordinances, can greatly

increase people’s comfort with trying bicycling. According to the Eugene Pedestrian and Bicycle

Strategic Plan, pedestrians are typically comfortable with walking distances of one mile, for

bicyclists that commuting distance extends to three miles (2008, p. 16). Supporting more

bicyclists, not only through infrastructure but also in education and learning of basic skills, will

greatly extend the reach and feasibility of bicycling as a commuting option. I will discuss more

equity issues with bicycling later in this section.

Two weeks into my internship, I thought that an FMPO collaboration with NAU on a

“car-free” flyer could be implemented into freshman orientation materials and possibly sent to

new students in advance of arriving at NAU. Knowing the different options for getting around

without a permanent car, including weekend getaways and traveling home, seemed like the

best way for both students and parents to feel comfortable not bringing a car to Flagstaff and

utilizing active transportation more. However, NAU freshman orientation coincided with the

start of my internship and was not able to be implemented for 2017. I did create the basic

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 41

information for a car-free flyer and hope this can be implemented to reduce car usage by the

large NAU student population.

I recommended that the FMPO have ongoing stakeholder meetings with departments

and businesses heavily involved in the tourism industry. I know first-hand that visitor center

employees have not received training on car-free options in Flagstaff as they relate to tourist

attractions and do not emphasize ways to reduce tourist car usage while spending time in the

community. This seems particularly important since there are 5.5 million visitors compared to

70,000 residents. Even if the FMPO were successful in getting total participation in active

transportation from residents, there would still be traffic congestion from visitors. Finding

ways to reduce that congestion by emphasizing urban trails and scenic walking routes,

emphasizing and expanding transit stops to tourist destinations, and bike sharing in strategic

locations could all be a means to reduce traffic congestion from visitors.

Further Infrastructure Recommendations

The first pilot bike share program was rolled out after my internship was completed and

had a fair amount of success. In a bike share program, I recommended that adult tricycles be a

part of the available options to address some equity issues. I also recommended that bikeshare

docking stations be located at some of the larger hotels with maps to downtown or other

economic centers, with the Chamber of Commerce or Convention Bureau being a possible

partner. With the new parking fees in the downtown area, I thought these bike share stations

could be an appealing option for tourists and keep a portion of the visitors from driving to

destinations in Flagstaff.

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 42

I recommended that the end of I-17 has an “Entering High Pedestrian and Bicycling

Area” sign and other calming measures. I think there is a problem between drivers going 75

mph on a freeway transitioning to Milton Road, particularly as more student housing is built in

this area with Milltown. First-time visitors in particular probably aren’t expecting this transition

from freeway to city.

Furthermore, the areas where there are the highest incidences of pedestrian and bicycle

crashes should have lighted crosswalks and more signage to help reduce crash rates. As well,

the new crosswalk measures could have an event with temporary signs making motorists aware

of crash issues in the location. The Sustainability Squirrel could attend to get motorists’

attention. Having police target crosswalk areas where there are large crash rates and ticket

motorists, pedestrians, and bicyclists for infractions could encourage safer behavior.

I recommended that the FMPO collaborate with Flagstaff Arts Council and Flagstaff

Artist Coalition to have more public commissioned art along FUTS trails that are created more

for commuter purposes than scenic beauty. The planned extensions on Lone Tree, JW Powell,

and West Rt. 66 all have potential to include artwork if they have safe infrastructure for walking

and biking. The FMPO could have a bicycle event around the completion of the new artwork.

Further Surveying Recommendations

In future surveys, I recommend that the FMPO ask participants where there should be

more bicycle parking. Depending on what type of bike share program is implemented in the

future, a survey about bike share locations should also be implemented. However, I think the

reach of this survey should heavily focus on NAU, as a part of the Green NAU newsletter. It also

should include paper surveys and outreach at the various shelters and food banks within the

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 43

community, as well as hotels. I think this survey strategy will target the most likely users of bike

share. Helmets and lighting for use at night are further details to be worked out by gathering

survey information from potential users and working with bike share provider.

I recommend that the FMPO collaborate with our bike enthusiast community by

periodically doing week-long audits on conditions during their bike commutes. The Flagstaff

Biking Organization, outreach at bike shops, and getting volunteers through BAC notices could

be a source of obtaining near-immediate “on the ground” data. From this data, the FMPO can

work with Public Works and other departments to address problem areas with snow, debris,

and other obstacles in a biking commute. A pedestrian audit could be done as well, particularly

during winter months when danger from ice and snow is greater, through a PAC notice.

Flagstaff Walks! Events Reflection

The idea behind Flagstaff Walks! is that by creating a culture of walking within a social

setting, people will be more willing to walk and bike as a

part of their transportation options and advocate more for

safe infrastructure. This is also the reason why FMPO

cross-promoted a lot more walking events held by other

Flagstaff organizations, including the Downtown Business

Alliance’s Meet Me Downtown, the Flagstaff Monuments

nature walks, bike shops social biking events, Willow

Bend’s Geology Walks, and Jack Welch’s weekly walk

events through the FUTS trails.

In the Flagstaff Walks! events that FMPO helped

Figure 27: Meet Me Downtown inaugural flyer

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 44

host, the public seemed to be enjoying the walks and they received physical activity and fresh

outdoor air. These events subjectively improved their quality of life and health on a temporary

basis. It may have even served as a reminder of why they chose Flagstaff as their home or a

place to visit.

However, I do not think these events translate into people walking and biking more as a

transportation option. There are a lot more cars parked around the neighborhood of the

Community Market on Sunday mornings where FMPO started many of the walks (a

neighborhood where I live and notice the regular increase of parked cars during market

season). There are not appealing active transportation options to the Coconino Forest hiking

trails. And through the low-

attendance at Meet Me Downtown

events and general complaining of the

newly enacted downtown paid

parking, most people attending these

social walking events are still driving

to them. These events add value to

the community, but are not the most

effective way to increase active

transportation participation.

Making the Case Reflection

The FUTS Facebook page

seemed like a good venue to share

Figure 28: Facebook post on walking quote by Edward Abbey

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 45

the information gathered in the Making the Case for Walking and Biking paper that I further

developed during my internship. The people who “like” the FUTS page are not necessarily

active transportation commuters but could be solely recreational users of the trails. I could

share bite-sized information to a digital crowd of 2,000, many who might not be sold on the

benefits of active transportation. In addition to the potential of getting a few converts, the

information could be easily shared digitally to a larger crowd and could even serve as a

conversation point in a discussion about active transportation in the future.

However, I really do not know if I was successful in any of those goals. Posting more

frequently on Facebook received more

views, and I was strategic on posting in the

middle of the day when Facebook use by

people is highest. But “likes” and “shares”

are a poor metric on whether I won any

hearts and minds to active transportation.

In fact, the most viewed and shared post

was not any of the carefully researched

information on the benefits of active

transportation – it was an Edward Abbey

quote about walking that I discovered

serendipitously and posted on a whim. My

follow-up experiment of an Anon quote

about biking also tracked well.

Figure 29: Facebook post with biking quote from Anon

PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION FLAGSTAFF 46

I am not certain that this information is significant. Perhaps people are more willing to

“like” soft information of the info-tainment variety. A photo of kittens and puppies in a bicycle

basket could possibly gather over 1,000 likes compared to a half dozen on researched data

about walking and biking. However, this does not mean that people did not reflect on the

research information provided on the FUTS Facebook page. This information likely did reach a

wider audience than if the information had solely been included in the Active Transportation

Master Plan, presentations to City Council, and at public meetings and outreach. FMPO shared

the data collected from “Making the Case” in infographics at the Active Transportation

Summits, but this information could have also been shared at tabling events for Flagstaff Walks!

and other events. There is also an opportunity to expand the online presence of this data

through Twitter, Snapchat, and Instagram, particularly among the student population at NAU.

Active Transportation Summits Reflection

One problem with having a small staff that partially consists of rotating interns is that

the interns will spend the beginning of their internship just learning the basics of the job and

building the wealth of knowledge that the other employees already possess (like any job).