1

Oce of the Provost

Guide to Equity-Based Graduate

Admissions

2

Affirmation of University Policies 3

Acknowledgments 4

Introduction to the Guide to Equity-Based

Graduate Admissions 5

Overview from the Executive Vice President for

University Life and Senior Vice Provost for Faculty

Advancement 6

Checklist 7

SECTION 1: OUTREACH AND RECRUITMENT 10

1.1. Recruitment events 10

Types of recruitment events 10

1.2. Targeted promotion and marketing 12

Traditional advertising sources 12

Nontraditional advertising sources 12

Organic marketing efforts 13

Website 14

1.3. Recruitment strategies 15

Targeted scholarships and fellowships 15

Partnerships with undergraduate institutions 15

Role of current students in the recruitment process 16

Partnerships and programming with existing national

and local pathways and leadership programs 18

Developing new pathways programs within your

discipline 18

Promotion of diversity statistics 19

Application fee waivers 19

Dedicated admissions office staffing for

recruitment of historically underrepresented

populations 20

SECTION 2: REVIEW AND SELECTION 22

2.1. Predicting success in your discipline/program 22

Test score interpretation 22

GPA/Transcript interpretation 22

2.2. Holistic and intentional review 22

2.3. Bias and holistic review workshops 23

Holistic review workshops 23

Implicit bias training 23

2.4. Developing a reader guide 24

Introduction 24

Diversity disclaimer 24

Diversity statement 24

Diversity goals 24

Rubric 24

Quantitative assessment 25

Qualitative assessment 25

2.5. Reviewing recommendation letters 25

How recommender comments align with

what you value in your applicants 25

Tone of the recommendation letter 25

Bias in the recommendation letter 25

Quality of the recommendation letter 25

2.6. Conducting interviews 26

How to decrease bias in an interview 26

SECTION 3: YIELD, ONBOARDING, AND STUDENT

SUPPORT 27

3.1. Yielding historically underrepresented students 27

Yield strategies and initiatives 28

Accepted applicant day 28

Funding opportunities 28

3.2. Onboarding—Programming to support historically

underrepresented students as they transition

to graduate school 28

Importance of onboarding historically

underrepresented students 28

Promising onboarding strategies and initiatives 29

3.3. Student experience and support—Programming

to support historically underrepresented students

through graduation 31

Importance of ongoing support for historically

underrepresented student populations 31

Promising student support strategies and initiatives 31

Conclusion 35

References 36

CONTENTS

3

AFFIRMATION OF UNIVERSITY POLICIES

The context for this guide is Columbia’s long-standing commitment to the principles of equity and excellence. Columbia actively

pursues both, adhering to the belief that equity is the partner of excellence.

In furtherance of this commitment, Columbia has implemented policies and programs to ensure that decisions (whether about

employment or admissions) are based on individual merit and not on bias or stereotypes. Columbia’s Non-Discrimination

Statement states, in part, the following: “Columbia University is committed to providing a learning, living, and working

environment free from unlawful discrimination and harassment and to fostering a nurturing and vibrant community founded

upon the fundamental dignity and worth of all of its members. Each individual has the right to work and learn in a professional

atmosphere that promotes equal employment opportunities and prohibits discrimination and discriminatory harassment. All

employees, applicants for employment, interns (paid or unpaid), students, contractors and people conducting business with the

University are protected from prohibited conduct.”

Hand in hand with its commitment to non-discrimination is Columbia’s commitment to diversity. Columbia’s Diversity Mission

Statement states, in part, the following:

Columbia is dedicated to increasing diversity in its workforce, its student body, and its educational programs. Achieving

continued academic excellence and creating a vibrant university community require nothing less.

Both to prepare our students for citizenship in a pluralistic world and to keep Columbia at the forefront of knowledge, the

University seeks to recognize and draw upon the talents of a diverse range of outstanding . . . students and to foster the

free exploration and expression of differing ideas, beliefs, and perspectives through scholarly inquiry and civil discourse.

In developing its academic programs, Columbia furthers the thoughtful examination of cultural distinctions by developing

curricula that prepare students to be responsible members of diverse societies.

In fulfilling its mission to advance diversity at the University, Columbia . . . strives to recruit members of groups traditionally

underrepresented in American higher education and to increase the number of minority and women candidates in its

graduate and professional programs.

This guide is prepared then in the spirit of ensuring equity and excellence. Nothing in it is intended to accord, or should in any

way be construed as according, any type of favoritism or preferential treatment to any applicant for admission.

4

Equity in Graduate Admissions Working Group

Outreach and Recruitment Subcommittee

• Erwin de Leon (School of Professional Studies)

• Julie Dobrow (School of the Arts) (group chair)

• Grace Han (School of International and Public Affairs)

• John Haskins (Columbia Journalism School)

• Wendy Hernandez-Quinones (Vagelos College of Physicians and

Surgeons)

• Eileen Lloyd (Programs in Occupational Therapy)

• Michael Lovaglio (School of Social Work)

• Keyauna Ramos (Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons)

• Natasha Stanislas (formerly at the School of Social Work)

• Afiya Wilson (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

Review and Selection Subcommittee

• Tarin Almanzar (Columbia Journalism School)

• Anne Armstrong-Coben (Vagelos College of Physicians and

Surgeons)

• Kristen Barnes (Office of the Provost)

• Cecilia Granda (formerly at the School of International and Public

Affairs)

• Shavonna Hinton (Columbia Engineering)

• Hilda Hutcherson (Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons)

• George Jenkins (College of Dental Medicine)

• Iessa Sutton (Office of the Provost)

Yield, Onboarding and Student Support Submommittee

• Katie Bucaccio (Columbia Business School)

• Celina Chatman Nelson (Graduate School of Arts and Sciences)

• Karma Lowe (School of Social Work)

• Laila Maher (School of the Arts) (group co-chair)

• Victoria Malaney-Brown (Columbia College | Columbia

Engineering)

• Kwame Osei-Sarfo (Columbia Engineering)

• Elizabeth Peiffer (Weatherhead East Asian Institute and Master of

Arts in Regional Studies: East Asia [MARSEA])

• Jessica Troiano (School of Social Work)

• Judy Wolfe (School of Nursing) (group co-chair)

• Tsuya Yee (School of International and Public Affairs)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This guide was made possible thanks to the

collaborative effort of admissions officers,

diversity officers, and student affairs staff across

the University who participated in the Equity in

Graduate Admissions Working Group. Thank you

for dedicating your time to research and write

about equity-based graduate admissions and for

sharing your Columbia University institutional

knowledge with your peers. Additional thanks

to all the admissions directors and officers

who participated in interviews to highlight best

practices in their specific schools and units. We

appreciate the guidance provided by the Inclusive

Faculty Pathways Advisory Council Working

Group: Professors Ruben Gonzalez, Kellie Jones,

and Desmond Patton, whose valuable early

feedback helped shape the format of the guide.

Many thanks to Callum Blackmore, Academic

Administration Fellow, who conducted an

extensive literature review for the guide, and to

members of the Faculty Advancement team—Jen

Leach, Marianna Pecoraro, and Vina Tran—who

copyedited the draft. This guide is the result

of the tireless efforts of Adina Berrios Brooks,

Associate Provost for Inclusive Faculty Pathways,

and Diana Dumitru, Associate Director for

Inclusive Faculty Pathways, who led the Equity

in Graduate Admissions Working Group and

managed this project through to completion.

5

INTRODUCTION TO THE GUIDE TO EQUITYBASED

GRADUATE ADMISSIONS

Dear member of the Columbia community,

Columbia University is committed to ensuring that our community of students and scholars

reflects a broad spectrum of backgrounds, identities, and perspectives. Equity-based

admissions is central to that work and critical to our aspirations to attract and prepare the

leading scholars and researchers of the future.

Thus, I am delighted to introduce this guide, which is one of the first projects of a new

Inclusive Faculty Pathways portfolio—an initiative of the Office of the Vice Provost for

Faculty Advancement—which seeks to increase access to our graduate and postdoctoral

programs for emerging scholars from historically underrepresented backgrounds.

The guide, the sixth volume in a growing library of diversity resources for the University,

consists of three sections: outreach and recruitment; review and selection; and yield,

onboarding, and student support. Each is a critical element in a comprehensive strategy to

attract and retain a student body that embodies inclusive excellence.

Although this guide was produced by the Office of the Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement,

the team informing its contents is far broader. We brought together diversity officers,

admissions officers, and student affairs and academic support staff from across the

University to share perspectives. The culmination of this work showcases the unique

approaches each of the graduate schools employs to attract and support a truly diverse

student population. It is excellent work that I hope will spark reflection and discussion.

I look forward to seeing this guide influence graduate admissions practices at Columbia and

to future editions that build upon the efforts reflected in this volume.

Sincerely,

Mary C. Boyce

Provost

Professor of Mechanical Engineering

6

OVERVIEW FROM THE EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT FOR

UNIVERSITY LIFE AND SENIOR VICE PROVOST FOR FACULTY

ADVANCEMENT

Dear Colleagues,

The Guide to Equity-Based Graduate Admissions is one of the first projects of the new

Inclusive Faculty Pathways (IFP) initiative. We hope that this tool will be used by all

those involved in graduate admissions to sharpen their equity lens in every aspect of the

recruitment, selection, and onboarding processes.

The creation of the guide resulted from the collaborative effort of the Equity in Graduate

Admissions Working Group, including thirty admissions officers, diversity officers, and student

affairs staff across the University, representing over fifteen schools and units. We know there

is so much exciting work happening at each of our schools, and we are thrilled to feature

these practices throughout the guide. The interviews with admissions officers enabled us to

highlight their best practices in specific schools and units across the University. This process

allowed us to break down the silos created by such a large institution.

This guide is divided into three parts: outreach and recruitment; review and selection; and

yield, onboarding, and student support and it provides guidelines for admissions committees

on best practices across the academy. In order to have the most diverse application pool

possible, it is essential to communicate the accessibility of Columbia to the graduate

community with intention. Once we create a diverse applicant pool, it is equally important to

provide guidance on processes for reviewing and selecting candidates, conducting a holistic

review, and reducing bias in interviews and recommendation letters. Finally, once the students

have been admitted, issues regarding yield, onboarding, and student experience and support

have to be addressed.

This work is ongoing: based on the research and feedback of the Inclusive Faculty

Pathways Advisory Council Working Group and the Yield, Onboarding, and Student Support

Subcommittee, we recognize the need for a future guide to delve deeper into the student

experience and support services offered at Columbia University.

This is a living document, and we look forward to receiving your feedback, which will be

incorporated into the printed version of the guide. Please email us with your suggestions at

inclusivefacultypathwa[email protected].

Best,

Dennis A. Mitchell, DDS, MPH

Executive Vice President for University Life

Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Advancement

Professor of Dental Medicine at CUIMC

7

CHECKLIST

Outreach and Recruitment

Recruitment events and school visits

□ Highlight unique aspects of the institutional culture or community during on-campus recruitment events

□ Facilitate interaction with diverse faculty, alumni, and current students during campus visits

□ Include visits to schools that have strong Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) representation including MSIs

and HBCUs

□ Host information sessions at schools that do not offer school fairs

Targeted promotion and marketing

□ Pair high-caliber print media with impactful in-person experiences to attract students

□ Incorporate images that authentically represent diversity in official printed advertising

□ Prioritize content that foregrounds testimony of students with lived experiences in the program

□ Showcase alumni stories to give potential applicants a sense of the career possibilities afforded by the program

□ Encourage faculty and staff members to personally reach out directly via social media to prospective candidates from

their networks

□ Make personal connections with prospective students at graduate fairs

□ Have a strong web presence and incorporate inclusive website design

Recruitment strategies: Partnerships

□ Provide targeted scholarships and fellowships to students from historically underrepresented backgrounds

□ Partner with undergraduate institutions and provide tailored programming to highlight the institution’s commitment to

diversity, equity, and inclusion

□ Involve current students (student ambassadors, student associations, student groups) in the recruitment process to

create personal connections and the feeling of belonging

□ Partner with national and local pathways leadership programs that can offer academic, social, and financial support for

students that are in the pathways programs across the University

□ Take advantage of the pathways programs within your discipline to attract historically underrepresented students*

Recruitment strategies: Transparency, fee waivers, and admissions officers

□ Be transparent about the diversity of your cohorts and about the strengths and weaknesses of the programs

□ Provide application fee waivers by partnering with nonprofit or governmental institutions

□ Hire a dedicated admissions officer to recruit students from historically underrepresented backgrounds

*For the purposes of this guide, the term “historically underrepresented students,” is defined as follows: Applicants who (i) are the first in their family to attend

graduate school; (ii) grew up in a single parent household; (iii) have—either as a result of their socioeconomic background, their status as a member of a historically

underrepresented group, their disability status, their LGBTQ status, or other challenging life experiences—overcome obstacles on their journey to graduate school;

or (iv) are members of a demographic group that is underrepresented in a particular Program relative to the demographic representation in peer institutions or relative

to the matriculation rates in bachelor’s and master’s fields of study that are feeders to the particular Program.

8

Review and Selection

Test scores and GPA interpretation

□ Interpret test scores, transcripts, and recommendations for evidence of proficiency as a whole

□ Look beyond the overall GPA for patterns that may provide clues about the applicant’s academic history

Holistic and intentional review

□ Take into consideration various attributes of the applicant

□ Consider the criteria of admissions within the context of departmental mission and goals for incoming graduate scholars

□ Focus your review based on a balance in applicants’ experience, attributes, and academic metrics

□ Give individualized consideration to each applicant

Workshops and trainings for admissions committee members

□ Provide holistic review workshops for the admissions committee members

□ Provide implicit bias training for the admissions committee members

Reader guide

□ Develop a reader guide for the admissions process within your department that includes a rubric, a diversity statement,

and a disclaimer

Recommendation letters

□ Consider the recommendation letter’s tone, bias, and alignment with institutional criteria

Interviews

To decrease bias in the interviewing process:

□ Require and provide bias training

□ Utilize standardized interview questions in the interviewing process

□ Develop a rubric for evaluating candidates

□ Provide a virtual background for the interviews to avoid bias based on room/location

□ Conduct asynchronous video interviews

9

Yield, Onboarding, and Student Support

Yield strategies and initiatives

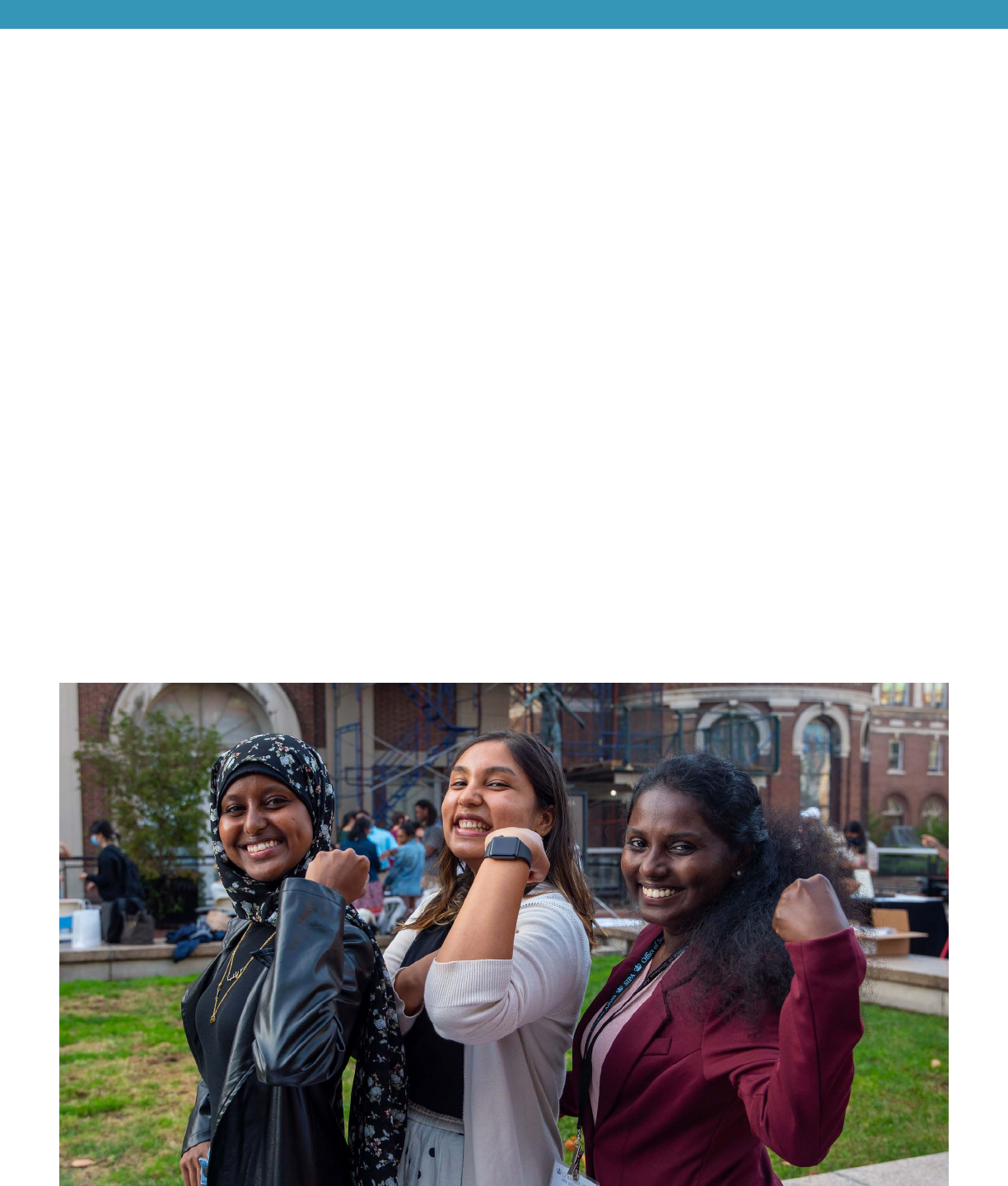

□ Organize events and networking opportunities with admitted students and faculty, alumni, or current students that align

with their social identities (BIPOC, first generation, LGBTQ, etc.)

□ Invite admitted students to existing school programming before they arrive on campus to integrate them into the

community

□ Organize an accepted applicants day that includes specific programming for historically underrepresented students

□ Consider fellowships and scholarships that, through neutral criteria, include historically underrepresented students

Onboarding strategies and initiatives

Provide early support strategies such as:

□ Summer bridge programs

□ Peer mentoring

□ Peer leadership

□ Coaching for social skills

□ Study groups

□ Early research opportunities

□ Mentoring of students by faculty

□ As part of new student orientations, include sessions led by trained staff on diversity

Develop wraparound programming for students such as:

□ Creating student affinity spaces

□ Providing opportunities for faculty, staff, and students to learn the values of inclusion and belonging and strategies

for supporting historically underrepresented students

□ Providing workshops on navigating the institution and accessing support services

□ Creating social media groups for the students to connect before they arrive

□ Providing resources for staff support positions, programming, and dedicated physical spaces for students

Student experience and student support initiatives and strategies

Develop and implement a supportive and inclusive environment through programs such as:

□ Professional development workshops

□ Networking opportunities (utilizing alumni networks)

□ Specialized advising

□ Job recruitment fairs

□ Faculty mentorship

□ Leadership training

□ Community building

□ Research and professional skills training modules

□ Personalized counseling services

□ Financial support for historically underrepresented

students

□ Encourage students to utilize diversity advising and academic support centers

10

Equity-based admissions practice requires a thoughtful and sustained recruitment strategy to cast the widest possible net.

This section covers recruitment events, marketing, and advertising and a vast array of recruitment strategies for historically

underrepresented graduate students.

1.1. RECRUITMENT EVENTS

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided challenges for in-person recruitment events, but it has also provided enhanced options

for virtual recruitment events that attract students worldwide. Students facing financial or geographic constraints are now able

to participate in more virtual recruitment events, providing them with opportunities to explore schools that otherwise would

have been inaccessible. Despite the return to in-person events, virtual and hybrid events are likely here to stay. Yet campus visits

can help foster emotional connections to campus and even promote a sense of belonging before the student has committed to

the institution. Prospective students are invariably attracted to the culture or climate of university campuses and the kinds of

communities that this climate affords.

Types of recruitment events

ONCAMPUS EVENTS

• Invited campus visits

• Recruitment weekends

• Open houses

• Preview days

• Admitted students events

• Scholarship events

• Road shows and other recruitment events hosted by

organizations and institutions around the world:

▫ National and international conferences

- SACNAS: https://www.sacnas.org/conference

- ABRCMS: https://abrcms.org/

- NOBCChE: https://www.nobcche.org/conference

▫ Grad school fairs

▫ School visits

Individual School highlights are provided throughout the guide

in the boxes shaded in blue.

VIRTUAL EVENTS

There are a number of ways to engage with prospective

students virtually:

• Live virtual campus tours

Columbia Engineering hosts a live virtual campus tour

every Thursday at 2:00 p.m.

• General virtual information sessions

These sessions help prepare students to complete and

submit their application to a graduate degree program.

• Program-specific information sessions

• Recordings of past information sessions

• Student panels

Current students share how they navigated the

application process and how they made the most of their

graduate student experience.

• Digital forums

Students have the opportunity to have their questions

regarding applying to Columbia’s programs answered in

real time.

• Webinars on submitting a strong application and

application tips

• Virtual student chats

• Virtual meetings with an admissions officer

• Webinars on deferred enrollment

SECTION 1: OUTREACH AND RECRUITMENT

11

The Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied

Science Graduate Admissions team is committed to

recruiting talented and promising students from all

backgrounds. Each year, the Graduate Student Affairs

Office attends multiple conferences and events to

increase the number of graduate students from historically

underrepresented groups in engineering and applied

science disciplines. The Graduate Admissions Office also

sponsors annual diversity recruitment events such as the

Engineering Achievers in Graduate Education (EngAGE).

When conducting in-person events at Columbia University,

utilize these strategies to attract and yield historically

underrepresented students:

• Highlight unique aspects of the institutional culture

or community (Secore 2019)

• Explicitly tailor the campus visit to historically

underrepresented students by facilitating

interaction with diverse faculty, alumni, and current

students (Perna 2004)

This strategy has been shown to play a critical role

in attracting students from diverse backgrounds

(McCallum 2020; National Association of Diversity

Officers in Higher Education [NADOHE] 2021; Toor

2022).

▫ Tours should highlight the ways in which the

institution supports historically underrepresented

students and fosters diverse intellectual

communities, emphasizing the institution’s

commitment to equity and inclusion while also

presenting the campus as a space for historically

underrepresented students to grow and succeed

▫ Meetings with existing staff and students should

be foregrounded: make space for historically

underrepresented students to describe the

campus culture and community in their own

words, so that prospective students get a strong

feel for the institutional environment

Practice highlight: Visits to other schools

Scholars recommend establishing and expanding

relationships with minority serving institutions (MSIs),

including historically Black colleges and universities

(HBCUs), Hispanic serving institutions (HSIs), and Tribal

Colleges and Universities (TCUs); universities where

Black, Latinx, and Indigenous students are strongly

represented; and universities with limited research

traditions, in order to attract graduate students from

historically underrepresented communities (Harvey and

Andrewartha 2013; Tienda and Zhao 2017; NADOHE

2021).

Here are recommendations when planning to visit other

schools:

• Determine which schools you would like to visit

Run a report on which schools your students

attended prior to enrolling at your school. Also

consider schools from where you would like more

students.

• Register to participate in graduate and

professional school fairs and academic and

industry conferences

Note: There is a registration fee associated with

participation.

• Host an information session

For schools that are not offering fairs or for schools

where you are seeking specific students, you may

reach out directly to their Career Service Offices or

Academic Departments to make arrangements to

host an information session about your program(s)

and meet their students and faculty.

• Partner with other schools/programs

Consider hosting a session for your individual school/

program or partnering with other schools to offer a

joint session discussing the benefits of your schools/

programs. You may get more interest for a session

where multiple (relevant) schools are represented.

12

1.2. TARGETED PROMOTION AND

MARKETING

Evidence suggests that students from underrepresented

backgrounds are more likely to apply for graduate programs

where diversity and inclusion is emphasized in marketing

materials and public relations campaigns (Garces 2012).

This marketing should accurately reflect the diversity of an

institution and should honestly outline the advantages and

disadvantages of graduate education for underrepresented

students (Harvey and Andrewartha 2013; NADOHE 2021).

Traditional advertising sources

Traditional advertising sources, in particular print advertising,

remain crucial to graduate student recruitment. Applicants

tend to find these sources of advertising more trustworthy

than alternative advertising sources such as social media

(Shaw 2013). As these materials have higher production

costs, it is likely that, even as a larger amount of labor power

and institutional focus is directed toward digital marketing,

traditional marketing sources will still take up the majority of

recruitment marketing budgeting (Shaw 2014). When utilizing

print advertising, keep in mind the following:

• Pair high-caliber print media with impactful in-

person experiences

Especially when paired with in-person experiences

such as campus visits or graduate study expos,

brochures and prospectuses can endow a graduate

program with a sense of importance, quality, or

gravitas.

• Incorporate images that authentically represent

diversity in official printed advertising material

In order to attract underrepresented applicants,

materials such as prospectuses or viewbooks

should visually depict members of marginalized or

underrepresented populations as pivotal, engaged

members of vibrant academic communities (Osei-Kofi

and Torres 2015). It is important to accurately depict

campus diversity rather than conforming advertising

materials to some predetermined or symbolic definition

of diversity (Pippert, Essenburg, and Matchett 2013).

In today’s rapidly shifting media landscape, traditional

media—if carefully targeted and efficiently deployed—plays

an important role in graduate student recruitment as part of

a larger, well-rounded, tightly integrated marketing strategy

(Pippert, Essenburg, and Matchett 2013). Although it is

often more formal or informational in tone than social media

advertising, print media can, through the inclusion of student

profiles and photos, provide prospective applicants with

vital insights into the ways in which culture, community, and

identity shape the graduate experience.

Nontraditional advertising sources

Social media is emerging as an increasingly powerful tool in

graduate recruitment, especially when it is integrated with

other, more traditional forms of outreach and advertising

(Cohen 2021; Garcia, Pereira, and Cairrão 2021). A 2020

survey of incoming graduate students found that Facebook

was the most widely used social media platform, followed by

Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn (Carnegie Higher Ed 2020).

The recommendation is to maintain an active and vibrant

social media presence with relevant and meaningful content

(Bresnick 2021). This can be accomplished in several ways:

• Create separate social media accounts for your

graduate admissions office in order to tailor social

media content to potential applicants

• Prioritize video content that can be shared across

the top three platforms (Carnegie Higher Ed 2020)

This video content should provide a dynamic digital

taste of campus life, prioritizing and representing the

diversity of the graduate student body.

• Prioritize content that foregrounds testimony of

students with lived experiences in the program

It is important that student recruitment marketing

feels “real”—that the words, video, and images used

transmit an authentic representation of the campus

environment (Times Higher Education 2022). A

2013 Guardian study found that, while prospective

university applicants used social media often, they also

viewed social advertising as more untrustworthy than

traditional advertising sources (Shaw 2013).

• Showcase alumni stories to give potential applicants

a sense of the career possibilities afforded by the

program

The successes of current students and alumni—

especially of students and alumni from historically

underrepresented backgrounds—may be prominently

13

featured on social media accounts to boost graduate

student recruitment.

• Engage with organizations that work with Black,

Latinx, and Indigenous students online such as

SACNAS or National Society of Black Engineers

(NSBE) (Carnegie Higher Ed 2020; University of

California, Irvine 2022)

• Host virtual campus tours via social media

Some social media tools (i.e., Facebook Live, 360˚

photographs) can be utilized to host virtual campus

tours for potential applicants to get to know the

campus and learn more about the program before

committing to an in-person visit.

• Create content that helps orient potential graduate

students to the culture, mission, and lifestyle of the

program

Applicants tend to use social media most when

“finalizing” their decision to apply to enroll in a program,

as a means of imagining their life as a student there

(Carnegie Higher Ed 2020; University of California,

Irvine 2022).

The School of the Arts incorporates a vibrant range

of multimedia content in promoting its programs to

prospective graduate students. With the help of external

consultants, it produces videos featuring its key MFA

programs, including interviews with students, faculty, and

alumni who highlight important aspects of the programs

for prospective applicants. Shorter videos highlighting

individual students, faculty, and staff, are also used—

primarily to create a stimulating visual presence in the

school’s social media advertising.

The School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) has

been conducting admissions outreach online for several

years. Its outreach is done through social media, a well-

subscribed admissions blog, virtual info sessions, 1:1

video chats, and Q&A sessions to reach people all over

the world.

The Columbia School of Social Work (CSSW), has

found content marketing to be its most effective and

economical marketing tool. Rather than committing funds

toward ads, it has leveraged School and University events

that are open to the public, crafting communications/

invitations to prospects, inquiries, and applicants,

inviting them to various samplings of the intellectual

offerings at CSSW and Columbia University. It manages

these communications in Slate and has been able to

measure engagement by open and click rates. A typical

event of this type generates a very high percentage of

engagement. Throughout the cycle, these metrics of

engagement have helped CSSW predict the likelihood to

apply and yield/enroll quite reliably.

Organic marketing efforts

Studies suggest that informal relationships with faculty are

a major factor in motivating students from underrepresented

populations applying to graduate programs (Perna 2004;

McCallum 2020). Interactions between faculty and

prospective students can be mobilized in outreach and

marketing campaigns in order to proactively encourage

minority students to apply (Toor 2022).

• Make social media a priority

Personal connections and outreach can be as effective

as traditional advertising. Often in a particular

14

department or school, the faculty and staff are the

experts, and they know the most qualified people or

schools, or they have online networks that include likely

candidates. The value of promoting their school by

sharing a post on social media far exceeds the effort

and time that task takes.

• Bring in a wide array of faculty and staff to ensure

that the reach is maximized, and make it easy for

them to engage

Admissions managers should prepare easy-to-retweet

or easy-to-reshare posts to social media, especially

LinkedIn, along with Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

These posts should be dynamic, perhaps with video

clips, or at least include some form of multimedia.

• Make social media a community effort, and engage

the staff—“social” means social

Offer staff and faculty tips or lessons on using different

platforms, including best practices on format and tone.

• Encourage staff members outreach

Encourage staff members to direct-message

individuals within their networks, with an emphasis

on reaching out to underserved or underrepresented

populations.

• Be ready to adopt new social platforms as they emerge

The Columbia Journalism School

has found that reaching out directly

to historically underrepresented

students has been the most effective

way of increasing the diversity of graduate admissions.

The school prioritizes interactions with underrepresented

candidates (at graduate fairs, in classrooms) in order

to speak directly to their priorities, interests, and

backgrounds. The goal is to show underrepresented

students, who may not have considered Columbia as a

viable option, that the Journalism School is a place where

they can comfortably grow and thrive.

Website

A strong web presence is increasingly vital to attract a large

and diverse applicant pool. In particular, consider:

• Creating websites that are easy to navigate

Important content and information should be made im-

mediately accessible to prospective applicants (Kittle

and Ciba 2001). Pages within an admissions website

should connect logically and meaningfully with each

other and with other sites in Columbia University’s web

ecosystem.

• Developing interactive content to encourage

website users to engage more extensively with the

interface

Examples include (Klein 2005):

▫ virtual tours

▫ embedded videos

▫ dropdown material

▫ “two-way” communication with prospective grad-

uate students (i.e., via a campus tour, a Zoom

event, or an email newsletter)

• Updating the website regularly to avoid “dead links”

or outdated information, and varying the content

presented

• Carefully monitoring admissions website data and

reevaluating website content

Admissions website data can indicate which materials

potential applicants are finding most useful or engag-

ing, which materials are easy for potential applicants

to find, and which design decisions may be necessary

(Klein 2005).

• Incorporating inclusive website design

This can be a powerful tool for attracting a diverse

range of applicants to graduate programs (Rogers and

Molina 2006).

▫ Include a statement encouraging historically

underrepresented candidates to apply to your

graduate programs and/or a statement outlining

the department or graduate school’s commitment

to diversity (Rios, Randall, and Donnelly 2019)

▫ Demonstrate to prospective applicants that di-

versity, inclusion, and accessibility are integral to

the school’s mission; embody these aspirations in

both form and content on the website

▫ Use of alt-text and other ADA features: caption-

ing on videos, proper contrast ratio, etc., to make

the website more accessible

15

1.3. RECRUITMENT STRATEGIES

Targeted scholarships and fellowships

Targeted scholarships and fellowships for students from

historically underrepresented backgrounds can play a

significant role in fostering inclusion and diversity in graduate

programs (Garces 2012; Harvey and Andrewartha 2013;

NADOHE 2021; NACAC and NASFAA 2022).

One way to recruit a diverse population is to promote the

existence of targeted scholarships in marketing tactics to

encourage eligible students to apply. This can be accomplished

several ways:

• Providing information on the school’s financial aid web

page

If your school has targeted scholarships, you should

provide a link to information and eligibility requirements

from your school’s main Financial Aid page.

• Highlighting targeted scholarships as part of overall

marketing campaign

If you are paying for advertisements, consider adding

a sentence and/or link highlighting the existence of

targeted scholarships.

• Use specific ads promoting targeted scholarships

If your School has the available budget, it can be useful

to place ads in niche media outlets specifically promoting

the targeted scholarships.

• Direct outreach to thought leaders

Perhaps the most efficient way to reach eligible students

is through their current academic connections. For

example, if you are promoting a targeted scholarship at a

graduate institution, you should contact academic deans

and department heads at potential feeder schools (such

as MSIs and HBCUs, etc.) and ask them to recommend

your program to eligible students.

Partnerships with undergraduate institutions

It is crucial for graduate schools to establish firm partnerships

with pipeline undergraduate institutions and to use these

partnerships to connect early with strong candidates for

graduate programs. Below are best practices to enhance

partnerships with undergraduate institutions:

• Create connections between prospective students

and faculty

Administrators should try to involve faculty as much

as possible in these partnerships in order to facilitate

informal connections between prospective students

and teaching staff. This may include having faculty

teach recruitment seminars at pipeline colleges to give

advanced undergraduates a taste of graduate education

(Woodhouse 2006).

• Use partnerships to connect with strong candidates

early

Scholars have suggested that conversations about

graduate school should begin as early as a prospective

student’s first year of college (Sutton 2021).

• Offer relevant curricular and cocurricular

programming

Partnerships with pipeline colleges should offer a range of

curricular and cocurricular programming for prospective

students to experience the academic and social

environment of the graduate program (Nichol 2020).

• Utilize your partnerships to increase diversity

Graduate programs can use their partnerships with

pipeline colleges to increase the diversity of their

recruitment efforts.

▫ Tailored programming

Graduate programs may tailor their programming

at partner colleges to underrepresented students,

using these workshops to stress the institution’s

commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (Brown

1997; Johnson 2008).

▫ Partnerships with HBCUs

Universities may also pursue partnerships with

HBCUs or other colleges with diverse student bodies

in order to strengthen the graduate pipeline for

underrepresented students (Tienda and Zhao 2017).

16

A best practice for professional programs such as

Occupational Therapy (OT) is to partner with other local

colleges such as CUNY, Brooklyn College, Queens

College, who serve as feeder schools that send applica-

tions interested in the OT profession. In addition, these

partnerships provide an opportunity to connect with pre-

health advising programs, as well as students at the end

of their undergraduate psychology programs.

Role of current students in the recruitment

process

Having current students play a role in the recruitment pro-

cess is vital in order to attract prospective students from

historically underrepresented backgrounds. This can only

be successful if current students selected to participate are

well-supported and have a sense of belonging in their school

and program (see Section 3). The current students’ involve-

ment in the admissions process can serve multiple purposes:

• To provide valuable feedback to the admissions

committee

• To give prospective students an opportunity to learn

more about student experiences at the university

Informal conversations between prospective students

and student ambassadors, student associations, or

student groups can create personal connections and

increase the feeling of belonging.

• To mentor prospective students on the application

process

Peer mentors can provide anonymous feedback to the

prospective students on their applications, personal

statements, and navigating the application process.

The strength of the College of Dental Medicine (CDM)

recruitment lies in the impactful role that the ambassador

students play in the admissions process. An hour before

the interview process begins, the ambassador students

provide an information session on CDM’s culture, safe-

ty and the day-to-day life at CDM. It’s impactful for the

prospective students to hear from current students and

their experiences at CDM. The lead ambassadors don’t

participate in the interviewing process, but they provide

the admissions team valuable feedback regarding the

candidates. The interviewing team, compiled of 20 vol-

unteer faculty members, conveys to the candidates the

family side of being at CDM and the Columbia advantage:

coming to Columbia is not an expense, but a lifetime

investment.

The Law School’s J.D. Admissions Office enhances their

admissions events through partnership with the Black

Law Students Association (BLSA), the Latinx Law Stu-

dents Association (LALSA), and the Native American

Law Student Association (NALSA). They hold informal

chats with the prospective students and also assist in

the recruitment process via letter writing campaigns

and phone-a-thons. In addition, the office facilitates the

connection of relevant student identity groups such as

women or LGBTQ+ groups with prospective students. The

office also organizes an informational service event called

“Connecting the Dots” that provides prospective appli-

cants to any law school general information about the

practice of law. This event provides both a needed service

by promoting the benefits of law school and highlights

Columbia’s programs in the process.

17

The OADI Student Delegation comprises MA and PhD

students with an interest in supporting and promoting

diversity, inclusion, and equity within the Graduate

School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). Serving year-long

appointments, delegates represent the Office of Aca-

demic Diversity and Inclusion (OADI) by participating in

student panels, speaking at admissions and recruitment

events, leading discussions, and promoting student

activities in order to foreground the voices, experiences,

and research of traditionally underrepresented students.

This is particularly important work as it not only engages

students from across academic departments, but also at

the different stages of their academic careers, providing

students with a community and opportunities to provide

informal mentorship.

The Institute of Human Nutrition distinguishes itself

through its strategic use of advertising their current

programming and webinars to national and international

organizations that have their target demographics such

as The Student National Medical Association (SNMA).

They also reach out to pre-health advisors, connect with

university student groups, and engage with historically

underrepresented students through personal outreach.

Provost Diversity Fellows

18

Partnerships and programming with existing

national and local pathways and leadership

programs

Developing and expanding relationships with organizations

that serve underrepresented populations has been shown

to help graduate schools improve the diversity of their

outreach and recruitment efforts (Garces 2012; Harvey and

Andrewartha 2013; Tienda and Zhao 2017).

Academic pathways and leadership programs allow for early

identification and cultivation of historically underrepresented

students, such as of first-generation, low-income, or Black,

Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) students with a

strong inclination toward graduate study and a career in

the professoriate. These programs often employ a holistic

approach that provides academic, social, and financial

support that enhances successful outcomes and ensures an

equitable environment for learning (Byrd and Mason 2021). In

reviewing and evaluating pathways and leadership programs,

it is essential that faculty and staff identify programs that

best fits their students’ needs. Pathways and leadership

programs may be broken down into the following categories:

• Region or institution course-based undergraduate

research

i.e., bridge or enrichment programs

• Government or privately funded initiatives with

multiple sites

i.e., National Institute of Health Research Initiative

for Scientific Enhancement (NIH-RISE) or Mays

Undergraduate Fellowship Program

• Feeder programs between institutions, and between

undergraduate and graduate programs within an

institution

• Specialized curricula programs

i.e., Annual Biomedical Research Conference for

Minority Students (ABRCMS) or Society for the

Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanic and Native

Americans in Sciences

Developing new pathways programs within

your discipline

Researchers stress the importance of identifying and

expanding the pipeline for historically underrepresented

students to attend graduate school. Institutions can increase

the diversity of their graduate programs by codifying

pathways opportunities for underrepresented students and

by recognizing and addressing inequities in this pathway

(Harvey and Andrewartha 2013; Winkle-Wagner and McCoy

2016; NADOHE 2021).

Columbia is home to many pathways programs that serve as

a bridge for candidates from historically underrepresented

groups to advance from high school to undergraduate studies,

undergraduate to graduate studies, graduate studies to

faculty positions, and junior faculty positions to research

SHPEP and MedPrep Columbia University Pathways Summer Program

19

independence. These programs serve a range of student

populations and represent a diverse number of programs

across the University.

In addition, in Fall 2021, as part of the new Inclusive

Faculty Pathways Initiative, the Office of the Vice Provost

for Faculty Advancement has convened an administrative

group called Columbia University Pathways Programs (CUPP)

that connects the staff and faculty who coordinate these

programs and organizes joint summer programming to create

a climate of inclusion and belonging for the participating

students.

Factors that make these programs effective:

• Research preparedness

Aid scholars in the development of an academic skill

set through the introduction of collaborative learning,

research methodologies and concepts, and the

development of practical and discipline-specific skills

and knowledge for graduate study. Scholars should

have the opportunity to conduct research, analyze

data, and present research results.

• Inclusion and belonging

Cultivate an effective learning, training, and working

environment where scholars feel respected, welcomed,

and included.

• Mentorship

Provide scholars with the opportunity to engage in a

reciprocal mentorship relationship that benefits the

mentee and mentor, and encourages the development

of both social capital (networking, access to resources)

and cultural capital (academic skill set and behavior

that fosters academic success).

• Financial support

Optimize scholars’ success by minimizing, or

alleviating, the financial burdens many first generation,

low-income (FGLI) and historically underrepresented

scholars encounter.

Promotion of diversity statistics

Recent studies urge graduate programs to be open and

transparent about the ways in which diversity impacts

admissions (NADOHE 2021; National Association for College

Admission Counseling [NACAC] and National Association

of Student Financial Aid Administrators [NASFAA] 2022).

Reflecting on diversity data—being honest about strengths

and weaknesses—can help institutions identify ways of

improving the admissions process for underrepresented

students (Toor 2022).

Application fee waivers

Application fees have been proven to deter many historically

underrepresented applicants from applying to graduate

school; many studies suggest that a broad-based application

fee waiver policy can help improve diversity in graduate

admissions (NADOHE 2021; NACAC and NASFAA 2022).

Committed to flexible and open practices in admissions,

Columbia School of Social Work has a very liberal applica-

tion fee waiver process. The fee is waived automatically

for veterans of the U.S. Armed Forces as well as for

alumni of AmeriCorps, Peace Corps, Teach for America,

McNair Scholars, the Higher Education Opportunity Pro-

gram (HEOP), Educational Opportunity Program (EOP),

and SEEK (CUNY). The school also invites any applicant

to request a fee waiver due to economic hardship.

SHPEP and MedPrep Columbia University Pathways Summer

Program

20

The School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) of-

fers fee waivers by partnering with programs such as The

Rangel Program, a U.S. State Department program, and

the Public Policy and International Affairs Program (PPIA),

a not-for-profit organization that has been supporting

efforts to increase diversity in graduate studies in public

policy and international affairs, and in public service.

Dedicated admissions office staffing for

recruitment of historically underrepresented

populations

By prioritizing equity and diversity in the composition and

practices of admissions offices, graduate programs can

help improve the admissions process for underrepresented

students (NACAC and NASFAA 2022).

Practice highlight: Recruitment staff

responsibilities

The sample job description below shows the main responsi-

bilities of a Recruitment and Admissions Coordinator whose

primary focus is recruitment of historically underrepresent-

ed students and promoting access and information. The

Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) has a

dedicated staff member in this position.

• The Recruitment and Admissions Coordinator helps

develop and implement a recruitment plan to facilitate

a strong and diverse applicant pool at VP&S. This role

works with HBCUs, CUNY, SUNY, and other colleges

that serve a diverse student body. The Recruitment and

Admissions Coordinator collaborates with the Office of

Diversity and Multicultural Affairs to facilitate a strong

and diverse applicant pool through presentations,

visiting colleges, attending college fair programs, and

communicating with prospective students throughout

the admission process. This not only includes HBCUs,

CUNY, and SUNY schools, but also our Columbia VP&S

pipeline programs.

• The Recruitment and Admissions Coordinator collab-

orates with other Columbia University departments to

increase diversity and access for various Columbia pro-

grams. Create work groups to discuss the goals of each

department and recruitment tactics that would allow

for maximum yield, including but not limited to flyers,

word-of-mouth, virtual presentations, workshops, and

electronic correspondence.

• Act as the liaison with various undergraduate admis-

sions offices, pre-health committees, and post-bac-

calaureate offices to plan and promote VP&S

outreach efforts.

• Establish and maintain relationships with applicants

during the admissions process and support their

needs throughout this time. Assist applicants from

schools that have fewer resources, in terms of sup-

port and guidance, who are interested in the field of

medicine.

• Collaborate with current students and faculty

members from a number of affinity groups to provide

information sessions for applicants interested in

these specific groups.

• Identify resources that will assist with the holistic

review and how we could best provide fairness for all

applicants. These resources discuss:

▫ Implicit/unconscious bias

▫ How we could reduce/neutralize implicit bias with-

in the admissions process

▫ Providing the additional resources on the sec-

ondary application system as a key resource for

screeners, interviewers, and admission committee

members involved in the admissions process.

21

SPREP Columbia University Pathways Summer Program

22

After casting a wide net for applicants, departments and

schools are faced with the challenge of equitably reviewing

and selecting candidates for admission. This section of the

guide will cover holistic review; the development and use of

a reader guide; and guidance around reviewing test scores,

transcripts, and letters of recommendation, as well as con-

ducting and evaluating interviews.

2.1. PREDICTING SUCCESS IN YOUR

DISCIPLINE/PROGRAM

While grade point average (GPA) and test scores are used to

evaluate an applicant’s intellectual potential, the key is to look

beyond total scores and review in great detail the academic

record for evidence of this trait.

Test score interpretation

Depending on what is being evaluated, test scores may be

used to assess the applicant’s English or foreign language

proficiency, aptitude, or scope of interest in and knowledge

of a particular subject area. However, if the test score is

slightly below what is required, then the application should be

reviewed carefully. In those cases, the reviewer should look at

the test (e.g., scores in each section), transcripts, and recom-

mendations for evidence of proficiency. In short, test scores

can help determine a student’s potential but should not be the

sole variable that determines the applicant’s admission.

GPA/Transcript interpretation

Grade point average can provide clues about the applicant’s

work ethic, and it may tell a story about the applicant’s will-

ingness to take risks or intellectual curiosity (e.g., attempting

classes outside a major). Similarly, a low GPA may be indicative

of a poor semester or academic year, which will pull down the

overall average. The applicant may have changed majors or

simply have had a bad semester for a host of reasons. While

reviewing the transcript, look for the applicant’s explanation

for any significant change in performance. When looking at

the transcript, don’t just rely on the GPA, but look for patterns

that may also give you clues about the applicant’s academic

history.

The Columbia School of Social Work (CSSW) applica-

tion includes optional questions that can help identify

students from historically underrepresented back-

grounds. For example, it includes questions on whether

the students are first-generation college students,

first-generation US citizens, or permanent residents;

Pell grant recipient information, which provides greater

distinction for assessing financial need; gender identity

or other LGBTQ+ identities; and a diversity statement.

These questions have had a positive impact on the school

overall, because they have raised awareness of LGBTQ+,

BIPOC, and other marginalized/underrepresented iden-

tities; the need to use proper pronouns; and the need

for financial assistance; and they have provided CSSW

a great way to track its recruitment efforts across these

student populations.

2.2. HOLISTIC AND INTENTIONAL REVIEW

With the growing recognition that standardized test scores

and GPAs do not capture the breadth of experiences and

qualities that an applicant brings to a university, many schools

have begun to incorporate “holistic reviews” into the admis-

sion process, with the goal of admitting a diverse body of stu-

dents that will not only excel academically but also have the

qualities needed for success (Artinian et al. 2017). In order

to capture the benefits of holistic review, programs should not

prescreen large numbers of students based on standardized

test scores and/or GPAs alone.

What is a holistic review?

A holistic review strategy is used to assess applicants’ unique

experiences, including their academic preparedness, antic-

ipated contribution to the incoming class, and potential for

success. The goal is to ensure attributes of the whole student

are taken into consideration during review.

Measuring such readiness skills and diversity alongside aca-

demic achievement measures (i.e., grades, test scores) consti-

tutes a “holistic admissions” process.

SECTION 2: REVIEW AND SELECTION

23

Research findings indicate that holistic review has a positive

impact on the academic unit, including increased diversity, the

admission of students who are better prepared for success,

and the admission of students who have faced barriers to

success in their lifetimes and who would have been excluded

under traditional admissions processes (Glazer et al. 2014).

Admissions committee members that utilize holistic review

also note an increased awareness of and sensitivity to

diversity. However, not all holistic reviews are equal. Being

equity-focused, in addition to considering a range of qualifi-

cations for admission, helps admissions committee members

be mindful of how they weigh certain qualities and criteria

relative to others. The criteria and their relative importance

should be considered within the context of the departmental

mission and goals for incoming graduate scholars.

2.3. BIAS AND HOLISTIC REVIEW

WORKSHOPS

Holistic review workshops

In committing to a holistic review of graduate school appli-

cants, admissions officers should be trained in a number of

aspects in the applicant review process. To encourage conver-

sation among faculty and staff responsible for selecting new

students, the training should be interactive and groups from

similar disciplines should be encouraged to attend together.

The workshops should cover a number of areas (Delplanque et

al. 2019), including:

• Discipline-specific skills/GPA assessment

Consider whether an applicant’s ability to engage

in certain research, service, mentoring, or teaching

opportunities may have been affected by other factors

other than choice (access, school offerings, necessity

to work extensively to pay for college expenses, etc.).

• Diversity

Discuss and consider tools to evaluate applicants’

contribution(s) to diversity through their experiences,

teaching, research, and/or service activities.

• Recommendation letters

Consider the questions that are asked of faculty in

their recommendation letters. Include opportunities for

participants to identify language within the letter(s) or

reference(s) to credentials that may signal bias.

• Personal statement

Build process for several admissions officers to review

the personal statement to gather multiple perspec-

tives. Encourage the use of a descriptive rubric that

delineates specific criteria.

• Personal background

Develop a plan to assess applicants’ personal circum-

stances and experiences (i.e., contribution to diversity,

obstacles overcome, first-generation status, participa-

tion in a graduate preparation program).

• Standardized test scores

Consider the equitable use of scores for all standard-

ized tests. If test scores are required, define clearly

how the applicants’ skills should be evaluated from

their test scores.

Implicit bias training

Implicit bias training is a beneficial, and arguably an essential,

first step to introducing admissions officers to the ways in

which implicit and explicit biases can influence decision-

making and behavior. To move toward equitable applicant

assessment, admissions officers should receive access to

materials that heighten awareness of implicit and explicit

bias and provide tools to mitigate bias in the applicant review

process. Some units are requiring bias training for those who

participate in admissions. For example, the Vagelos College

of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S) requires bias training for

all faculty and administrators who have an active role in the

admissions process.

The literature recommends that schools develop a plan to

identify and reduce implicit biases in the admission process.

The plan should not only document the overall process but

also state admissions criteria, and points of interactions

with applicants, and identify attributes indicative of student

success. Recommendations for admissions officers’ activity

include (Hardy 2020):

• participation in formalized implicit bias training(s) to

allow time for adequate self-reflection prior to the

admissions process;

24

• opportunities to read and review research findings on

systematic bias; and

• implicit bias knowledge attainment through training,

workshops, seminars, and/or reviewing relevant

literature.

Columbia Law School’s Office of Graduate Degree Pro-

grams (OGP) was awarded one of the school’s Antiracism

Grantmaking Program Awards for 2022. Entitled “You

Belong Here,” the project aims to help identify and remove

bias in admissions processes, including by increasing

awareness of the Law School’s institutional commitment

to inclusive and non-discriminatory admissions practices,

creating an inclusive community at the admissions and

recruitment stage, and providing professional develop-

ment for staff to advance these initiatives.

2.4. DEVELOPING A READER GUIDE

Introduction

A reader guide is a brief outline of how the reading process

will be conducted, including a timeline and explanation of

procedures, evaluation criteria, and overall admission goals.

Benefits of a reader guide include:

• ensuring an intentional review of the application pro-

cess;

• defining standards and best practices for all readers;

• creating a written framework of accountability for con-

sistent review of all applicants; and

• using the guide as a reference for long-term readers

and as a training tool for new readers.

If a School has different applications for each program, a

different reader review process, or different diversity goals

within programs, it is strongly recommended that a reader

guide be created for each unique process or goal.

Diversity disclaimer

This is an opportunity to share your school’s diversity dis-

claimer with all applicants. Sample language from the SIPA

guide: (insert school name) does not discriminate based on

race, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion,

age, national or ethnic origin, political beliefs, veteran status,

or disability unrelated to job or course of study requirements.

Diversity statement

A diversity statement is a written commitment to diversity,

equity, and inclusion toward a school’s constituents: students,

faculty, staff, and alumni.

Diversity goals

A school may have overall diversity goals, and each program

may have different or more specific diversity goals based on

the demographics of its current historically underrepresent-

ed student populations. If applicable, define diversity goals

specific to the school and include the program goals within

the program-specific reader guides.

Rubric

Develop and use a rubric that includes quantitative and quali-

tative assessments that are the same for all applicants.

The Mailman School of Public Health revised its admis-

sions rubric in 2018 in order to increase the diversity of

its graduate cohorts. Under the new rubric, readers were

asked to assess academic preparedness using a holistic

review (including coursework and extracurricular/profes-

sional experience and no longer assessing standardized

test scores). The school has also instituted implicit bias

training for readers in order to ensure that equity and

inclusion remain foregrounded throughout this process.

25

Quantitative assessment

Assign a points system based on the main categories of

an ideal candidate. This may include, but is not limited to,

academic achievement; professional experience; research

contributions; industry fit; alumni potential; and the referenc-

es/recommendations, essay, video, and interview collected in

the application.

Qualitative assessment

This can be captured in an open-ended note or comment sec-

tion and offers the opportunity for the reader to defend how

they arrived at their decision.

• It is important to share examples of qualitative as-

sessments that are free from implicit and explicit

bias. Creating an optional description that flags or

brings special attention to an applicant that meets the

diversity criteria established in the school’s definition of

underrepresented students provides additional context

for admission decisions.

• Making selection decisions without any qualitative as-

sessment is not permissible. If you admit someone with

the same quantitative score as a rejection, you must be

able to state a reason tied to the rubric for admission.

2.5. REVIEWING RECOMMENDATION

LETTERS

Recommendation letters, while helpful, should be used in a

supportive capacity in application review. The goal is to use

the letter to amplify positives about the applicant, not to look

for reasons to deny or diminish candidacy. With the exception

of times when recommenders clearly are not supportive of an

applicant, it can be challenging to discern what message a

recommender is sending. As a reviewer, consider the following:

How recommender comments align with what

you value in your applicants

• Consider developing a rubric that you can use to align

the recommendation with your institutional criteria.

Tone of the recommendation letter

• Is it a letter of minimal assurance; e.g., short, succinct,

and without much depth?

• Is it a letter of evaluation, e.g., highlighting strengths

and weaknesses while still reading as affirming?

Bias in the recommendation letter

• As you review, consider what is missing and/or not said

in the recommendation and which adjectives are or

aren’t used to describe students.

For example: Are women applying to STEM-related

areas being described as curious, creative, scientific?

Perhaps, but men will likely be viewed as more “STEM-

aligned” than women will. This should not be seen as a

negative but rather as an opportunity to more closely

evaluate their research interests and other components

of their application.

• Think about how gender norms affect the way recom-

menders perceive the person they are recommending.

For example: Those who present as female are por-

trayed more as students and teachers, while those who

present as male are portrayed more as researchers and

professionals.

• Learn and discuss the current research on biases and

assumptions within your field, and consciously strive

to minimize their influence on your evaluation. Studies

have shown that the more we are aware of discrepan-

cies between the ideals of impartiality and actual per-

formance, together with strong motivation to respond

without prejudice, the more we can effectively reduce

prejudicial or biased behavior (Devine et al. 2002).

Quality of the recommendation letter

• Consider that evaluators are more likely to rely on

underlying assumptions and biases when they do not

have sufficient time to devote to evaluations. To help

mitigate these impacts, develop and prioritize evalu-

ation criteria prior to evaluating candidates and apply

them consistently to all applicants.

• Research shows that different standards may be used

to evaluate male and female applicants and that when

criteria are not clearly articulated before reviewing can-

didates, evaluators may shift or emphasize criteria that

26

favor candidates from well-represented demographic

groups (Biernat and Fuegen 2001; Uhlmann and Cohen

2005).

2.6. CONDUCTING INTERVIEWS

The interview gives the school a chance to learn more about

the applicants, their interests, and how they’ll be able to

contribute to the school. In addition, an interview provides a

school with an opportunity to give applicants more informa-

tion about the school and answer any questions. Participation

in the interview process also allows the students to tell their

own story. Done well, an interview can also serve as a yield

tool for historically underrepresented students, especially if

the applicant’s concerns and priorities around belonging and

inclusion are addressed.

The Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons (VP&S)

emphasizes the importance of interviewing and face-

to-face interaction in its graduate admission process.

Interviews also provide admissions officers the opportu-

nity to assess candidates based on a holistic approach.

VP&S has found that a personal connection, and citing

specific details from a candidate’s application, increases

the applicant’s sense of inclusion and belonging and can

help increase the diversity of accepted applicants.

How to decrease bias in an interview

It is necessary to examine personal and professional biases

that can surface in the interview process, particularly those

that may be amplified in a virtual setting (Huppert et al.

2021). Implicit bias (also called unconscious bias) can affect a

person’s behavior without conscious recognition. It is important

to explicitly discuss this with interviewers in advance of

either in-person or virtual interviews (Huppert et al. 2021).

Below are recommendations to decrease bias in the interview

process:

• Require and provide bias training

Require and provide training on unconscious bias and

other biases for all recruiters and administrators in-

volved in applicant assessment, including interviews.

• Utilize standardized interview questions

Schools should consider the use of standardized

interview questions, which discourages questions that

are not directly relevant to applicant qualifications and

ensures consistency across the process.

• Develop an interview rubric for evaluating candi-

dates

This will ensure that reviewers evaluate applicants

consistently and in alignment with program goals.

• For virtual interviews:

▫ Provide a virtual background and recommend that

all interviewees use it

Consider asking applicants to use the same video

background when interviewing to avoid implicit bias

based on their room/location.

▫ Conduct asynchronous video interviews

The interviewees are provided with predetermined

questions with a set amount of time to record their

answers. Because of the lack of real-time interaction,

there are fewer opportunities for biases to surface.

27

In previous sections of this guide, we reviewed the practices

for recruiting and selecting talented applicants from histor-

ically underrepresented groups for graduate programs. We

then distilled promising practices that are most likely to prove

effective in the Columbia University context. We turn now to

the question of how to move talented students from admis-

sion to enrollment, and through their matriculation to gradua-

tion and beyond.

3.1. YIELDING HISTORICALLY

UNDERREPRESENTED STUDENTS

There is a general lack of research on graduate student col-

lege choice (Wall Bortz et al. 2020). Yield strategies in STEM

graduate education are based largely around what competi-

tors are doing, rather than what actually makes a difference