OPERATION WARP

SPEED

Accelerated COVID-

19 Vaccine

Development Status

and Efforts to Address

Manufacturing

Challenges

Report to Congressional Addressees

February 2021

GAO-21-319

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-21-319, a report to

congressional

addressees

February 2021

OPERATION WARP SPEED

Accelerated

COVID-19 Vaccine Development Status

and

Efforts to Address Manufacturing Challenges

What GAO Found

Operation Warp Speed (OWS)—a partnership between the Departments of

Health and Human Services (HHS) and Defense (DOD)—aimed to help

accelerate the development of a COVID-19 vaccine. GAO found that OWS and

vaccine companies adopted several strategies to accelerate vaccine

development and mitigate risk. For example, OWS selected vaccine candidates

that use different mechanisms to stimulate an immune response (i.e., platform

technologies; see figure). Vaccine companies also took steps, such as starting

large-scale manufacturing during clinical trials and combining clinical trial phases

or running them concurrently. Clinical trials gather data on safety and efficacy,

with more participants in each successive phase (e.g., phase 3 has more

participants than phase 2).

Vaccine Platform Technologies Supported by Operation Warp Speed, as of January 2021

As of January 30, 2021, five of the six OWS vaccine candidates have entered

phase 3 clinical trials, two of which—Moderna’s and Pfizer/BioNTech’s

vaccines—have received an emergency use authorization (EUA) from the Food

and Drug Administration (FDA). For vaccines that received EUA, additional data

on vaccine effectiveness will be generated from further follow-up of participants

in clinical trials already underway before the EUA was issued.

Technology readiness. GAO’s analysis of the OWS vaccine candidates’

technology readiness levels (TRL)—an indicator of technology maturity—

showed that COVID-19 vaccine development under OWS generally followed

traditional practices, with some adaptations. FDA issued specific guidance that

identified ways that vaccine development may be accelerated during the

pandemic. Vaccine companies told GAO that the primary difference from a non-

pandemic environment was the compressed timelines. To meet OWS timelines,

View GAO-21-319. For more information,

contact

Karen L. Howard and Candice N.

Wright

at (202) 512-6888 or

Why GAO

Did This Study

As of

February 5, 2021, the U.S. had

over

26 million cumulative reported

cases of COVID

-19 and about 449,02

0

reported deaths, according to the

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. The country also continues

to experience serious econo

mic

repercussions

, with the unemployment

rate and number of unemployed

in

January 2021

at nearly twice their pre-

pandemic levels

in February 2020. In

May 2020, OWS was launched and

included a goal of producing 300

million doses of safe

and effective

COVID

-19 vaccines with initial doses

available

by January 2021. Although

FDA has authorized two vaccines for

emergency use, OWS has not

yet met

its production goal

. Such vaccines are

crucial to mitigate the public health and

economic impacts of the

pandemic.

GAO

was asked to review OWS

vaccine development efforts

. This

report examines

:

(1) the characteristics

and status of the OWS vaccines, (2)

how developmental processes have

been adapted to meet OWS timelines,

and (3) the challenges that

companies

have faced

with scaling up

manufacturing and the steps they are

taking to address those challenges.

GAO administered a questionnaire

based on

HHS’s medical

countermeasures

TRL criteria to the

six

OWS vaccine companies to

evaluate

the COVID-19 vaccine

development proc

esses. GAO also

collected and reviewed supporting

documentation on vaccine

development and conducted interviews

with representa

tives from each of the

companie

s on vaccine development

and manufacturing

.

some vaccine companies relied on data from other vaccines using the same

platforms, where available, or conducted certain animal studies at the same time

as clinical trials. However, as is done in a non-pandemic environment, all vaccine

companies gathered initial safety and antibody response data with a small

number of participants before proceeding into large-scale human studies (e.g.,

phase 3 clinical trials). The two EUAs issued in December 2020 were based on

analyses of clinical trial participants and showed about 95 percent efficacy for

each vaccine. These analyses included assessments of efficacy after individuals

were given two doses of vaccine and after they were monitored for about 2

months for adverse events.

Manufacturing. As of January 2021, five of the six OWS vaccine companies had

started commercial scale manufacturing. OWS officials reported that as of

January 31, 2021, companies had released 63.7 million doses—about 32 percent

of the 200 million doses that, according to OWS, companies with EUAs have

been contracted to provide by March 31, 2021. Vaccine companies face a

number of challenges in scaling up manufacturing to produce hundreds of

millions of doses under OWS’s accelerated timelines. DOD and HHS are working

with vaccine companies to help mitigate manufacturing challenges, including:

• Limited manufacturing capacity: A shortage of facilities with capacity to

handle the vaccine manufacturing needs can lead to production bottlenecks.

Vaccine companies are working in partnership with OWS to expand

production capacity. For example, one vaccine company told GAO that

HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority helped

them identify an additional manufacturing partner to increase production.

Additionally, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is overseeing construction

projects to expand capacity at vaccine manufacturing facilities.

• Disruptions to manufacturing supply chains: Vaccine manufacturing supply

chains have been strained by the global demand for certain goods and

workforce disruptions caused by the global pandemic. For example,

representatives from one facility manufacturing COVID-19 vaccines stated

that they experienced challenges obtaining materials, including reagents and

certain chemicals. They also said that due to global demand, they waited 4 to

12 weeks for items that before the pandemic were typically available for

shipment within one week. Vaccine companies and DOD and HHS officials

told GAO they have undertaken several efforts to address possible

manufacturing disruptions and mitigate supply chain challenges. These

efforts include federal assistance to (1) expedite procurement and delivery of

critical manufacturing equipment, (2) develop a list of critical supplies that are

common across the six OWS vaccine candidates, and (3) expedite the

delivery of necessary equipment and goods coming into the United States.

Additionally, DOD and HHS officials said that as of December 2020 they had

placed prioritized ratings on 18 supply contracts for vaccine companies under

the Defense Production Act, which allows federal agencies with delegated

authority to require contractors to prioritize those contracts for supplies

needed for vaccine production.

• Gaps in the available workforce: Hiring and training personnel with the

specialized skills needed to run vaccine manufacturing processes can be

challenging. OWS officials stated that they have worked with the Department

of State to expedite visa approval for key technical personnel, including

technicians and engineers to assist with installing, testing, and certifying

critical equipment manufactured overseas. OWS officials also stated that

they requested that 16 DOD personnel be detailed to serve as quality control

staff at two vaccine manufacturing sites until the organizations can hire the

required personnel.

Page i GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Letter 1

Background 6

OWS Supported a Range of Vaccine Approaches 10

COVID-19 Vaccine Development Generally Followed Traditional

Practices, with Some Adaptations 20

OWS Vaccine Companies Face Challenges to Scaling Up

Manufacturing and Are Taking Steps to Help Mitigate Those

Challenges 26

Agency Comments and Third-Party Views 29

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 32

Appendix II The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS)

Technology Readiness Level (TRL) definitions 35

Appendix III Operation Warp Speed Dashboard 38

Appendix IV GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 39

Related GAO Products 40

Tables

Table 1: Typical Phases of Clinical Trials 8

Table 2: Characteristics for Each Operation Warp Speed Vaccine

Candidate, as of January 2021 17

Table 3: Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) for Each Operation

Warp Speed (OWS) Vaccine Candidate, as of January

2021 21

Table 4: Department of Health and Human Services’ Integrated

Technology Readiness Level (TRL) Scale and Definitions 35

Contents

Page ii GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figures

Figure 1: Traditional Vaccine Development Timeline Compared To

Potential Operation Warp Speed (OWS) Timeline 3

Figure 2: Traditional Vaccine Development Process 7

Figure 3: Department of Health and Human Services’ Integrated

Technology Readiness Level (TRL) Countermeasure

Scale and the Traditional Vaccine Development and

Manufacturing Processes 10

Figure 4: Overview of the Four Vaccine Platform Technologies

Considered by Operation Warp Speed, as of January

2021 12

Figure 5: The Process for mRNA Vaccines Generating Antibodies

to Protect Individuals from COVID-19 14

Figure 6: The Process for Replication-defective Live-vector

Vaccines Generating Antibodies to Protect Individuals

from COVID-19 15

Figure 7: The Process for Recombinant-subunit-adjuvanted

Protein Vaccines Generating Antibodies to Protect

Individuals from COVID-19 16

Figure 8: Operation Warp Speed Vaccine Candidates’ Clinical

Trials Schedule as Shown on the clinicaltrials.gov

Website as of January 30, 2021 25

Page iii GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Abbreviations

ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

BARDA Biomedical Advanced Research and Development

Authority

BLA biologics license application

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CGMP current good manufacturing practice

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

DOD Department of Defense

EUA emergency use authorization

FDA Food and Drug Administration

GLP good laboratory practice

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

IND Investigational New Drug

mRNA messenger RNA

OWS Operation Warp Speed

R&D research and development

TRL technology readiness level

VRBPAC Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory

Committee

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

February 11, 2021

Congressional Addressees

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has resulted in

catastrophic loss of life and substantial damage to the global economy,

stability, and security. Worldwide, as of February 5, 2021, there were over

104 million cumulative reported cases and over 2.2 million reported

deaths due to COVID-19; within the United States, there were over 26

million cumulative reported cases and 449,020 reported deaths.

1

The

country also continues to experience serious economic repercussions

and turmoil as a result of the pandemic.

2

In response to this

unprecedented global crisis, the federal government has taken a series of

actions to protect the health and well-being of Americans. Notably, in

March 2020, Congress passed, and the President signed into law, the

CARES Act, which provided over $2 trillion in emergency assistance and

health care response for individuals, families, and businesses affected by

COVID-19.

3

More recently, in December 2020, the Consolidated

1

Worldwide data from the World Health Organization reflect laboratory-confirmed cases

and deaths reported by countries and areas. Data on COVID-19 cases in the United

States are based on aggregate case reporting to the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) and include probable and confirmed cases as reported by states and

jurisdictions. According to CDC, the actual number of COVID-19 cases is unknown for a

variety of reasons, including that people who have been infected may have not been

tested or may have not sought medical care. CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics’

COVID-19 death counts in the United States are based on provisional counts from death

certificate data, which do not distinguish between laboratory-confirmed and probable

COVID-19 deaths. Provisional counts are incomplete due to an average delay of 2 weeks

(a range of 1–8 weeks or longer) for death certificate processing.

2

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation Summary—January 2021,

(Washington, D.C.: Feb. 2021). In January, the unemployment rate was 6.3 percent and

the number of unemployed persons was 10.1 million. Although both measures are much

lower than their April 2020 highs, they remain well above their pre-pandemic levels in

February 2020 (3.5 percent and 5.7 million, respectively).

3

Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020). As of January 1, 2021, four other relief laws

were also enacted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: the Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, 134 Stat. 1182 (2020); Paycheck

Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, Pub. L. No. 116-139, 134 Stat.

620 (2020); Families First Coronavirus Response Act, Pub. L. No. 116-127, 134 Stat. 178

(2020); and the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations

Act, 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-123, 134 Stat. 146.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Appropriations Act, 2021, provided additional federal assistance for the

ongoing response and recovery.

The development of a COVID-19 vaccine was crucial to mitigating the

public health and economic impacts of the virus. By the end of March

2020, with the initiation of the first clinical trials, the race was on in the

United States to develop a vaccine. On December 14, 2020, the United

States took an important step to protect the public against the virus as the

first vaccine shots—developed in a shorter time than any previous

vaccine—were administered.

As part of the U.S. vaccine effort, on May 15, 2020, the federal

government announced Operation Warp Speed (OWS), a partnership

between the Department of Defense (DOD) and Department of Health

and Human Services (HHS). As stated on the HHS website, the goal was

to produce 300 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines, with initial doses

available by January 2021. Although FDA has authorized two vaccines for

emergency use, OWS has not yet met its production goals.

4

Our

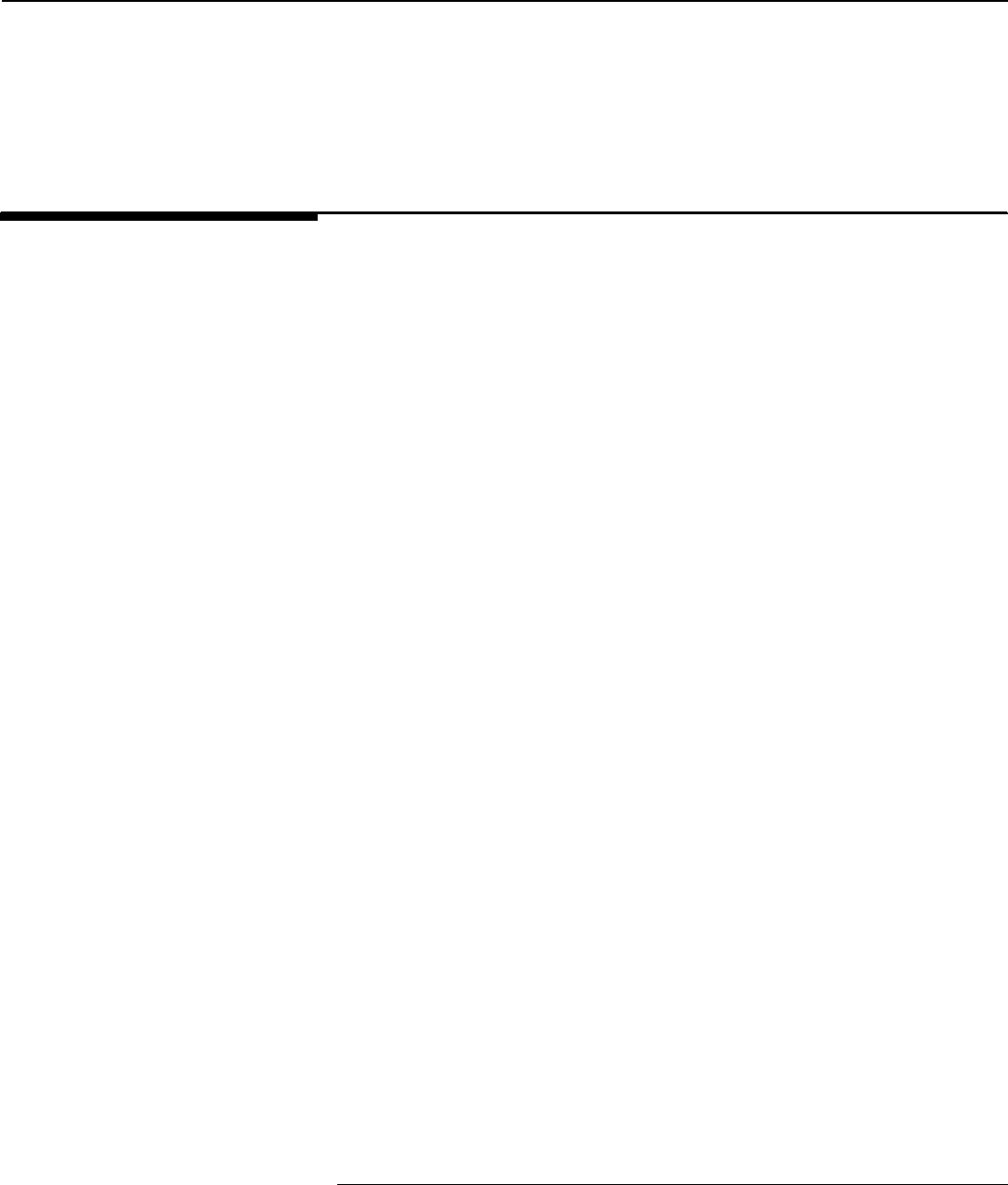

November 2020 report included the following figure describing how the

federal government aimed to accelerate the development of a COVID-19

vaccine (see fig. 1).

5

DOD and HHS have obligated approximately $13

billion as of December 31, 2020, to support the development,

manufacture, and distribution of vaccines to help achieve this goal.

6

4

During an emergency, as declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services under

21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3(b), FDA may temporarily authorize unapproved medical products or

unapproved uses of approved medical products through an emergency use authorization

(EUA), provided certain statutory criteria are met.

5

GAO, COVID-19: Federal Efforts Accelerate Vaccine and Therapeutic Development, but

More Transparency Needed on Emergency Use Authorizations, GAO-21-207

(Washington, D.C.: November 17, 2020).

6

GAO, COVID-19: Critical Vaccine Distribution, Supply Chain, Program Integrity, and

Other Challenges Require Focused Federal Attention, GAO-21-265 (Washington, D.C.:

January 28, 2021).

Page 3 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 1: Traditional Vaccine Development Timeline Compared To Potential Operation Warp Speed (OWS) Timeline

Note: The timelines for vaccine development depicted in this figure are not drawn to scale. These

timelines depict examples, and the specific development steps and timelines for a given vaccine may

vary from this example.

a

Phase 1 clinical trials generally test the safety of a product with a small group of healthy volunteers

(usually fewer than 100). These trials are designed to determine the product’s initial safety profile and

the side effects associated with increasing doses, among other things.

Phase 2 clinical trials are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a product for a particular use and

determine the common short-term side effects and risks associated with the product. These trials are

conducted with a medium-size population of volunteers (usually a few dozen to hundreds).

Phase 3 clinical trials are performed after preliminary evidence suggesting effectiveness of a product

has been obtained, and are intended to gather additional information about safety and effectiveness.

These trials usually involve several hundred to thousands of volunteers, including participants who

are at increased risk for infection. According to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officials, these

clinical trial phases may overlap.

b

According to FDA, manufacturing processes are reviewed as part of the vaccine licensure process.

Thus, even under a traditional vaccine timeline, some initial manufacturing occurs during

development, so the manufacturing processes can be adequately validated. According to an OWS

fact sheet, in some cases, the federal government is taking on the financial risk to enable large-scale

Page 4 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

manufacturing to start while clinical trials are ongoing, with the goal of having millions of doses

available for distribution upon authorization or licensure of a COVID-19 vaccine.

c

The OWS timeline depicts an example of a potential accelerated timeline for COVID-19 vaccine

development. However, the development process of any given OWS vaccine candidate may vary

from this example. As of January 2021, approximately 12 months have elapsed since exploratory and

preclinical research began in January 2020, after the first U.S. cases of COVID-19 were reported.

The timing for any remaining steps have yet to be determined as of this report. According to OWS

documentation, certain steps may overlap or be shortened to accelerate the development of a

COVID-19 vaccine.

d

During an emergency, as declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services under 21 U.S.C.

§ 360bbb-3(b), FDA may temporarily authorize unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of

approved medical products through an emergency use authorization (EUA), provided certain statutory

criteria are met. FDA has indicated that issuance of an EUA for a COVID-19 vaccine for which there

is adequate manufacturing information would require the submission of certain clinical trial

information from phase 3 clinical trials that demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine in

a clear and compelling manner, among other things. Any COVID-19 vaccine that initially receives an

EUA from FDA is expected to ultimately be reviewed and receive licensure through a biologics

license application, according to FDA guidance.

Vaccines provide protection for individuals and, more broadly,

communities, to lower transmission and disease burden once a large

enough portion of the population—typically 70 to 90 percent—develops

immunity.

7

Reaching this “herd immunity threshold” limits the likelihood

that a non-immune person will be infected. Herd immunity helps protect

people who are not immune to a disease by reducing their chances of

interacting with an infected individual, thereby slowing or stopping the

spread of the disease. Achieving herd immunity can require a high rate of

vaccination in the community, and can bring about a safe return to use of

restaurants, theaters, and gyms, and the resumption of community-based

activities. In this way, vaccines can save lives, reduce the sometimes

debilitating effects of COVID-19, and contribute to the restoration of the

economy.

You asked us to assess the technology readiness and manufacturing

status of OWS vaccine candidates. This report examines (1) the

characteristics and development status of the individual OWS vaccine

candidates, (2) how developmental processes have been adapted to

meet OWS timelines, and (3) the challenges that companies have faced

with scaling up manufacturing and the steps they are taking to address

those challenges.

To examine the characteristics and development status of the OWS

vaccine candidates, we analyzed relevant agency documents, vaccine

company documents, and journal articles. To examine how

7

Disease burden is the impact of a health problem as measured by mortality, morbidity,

financial impact, or other indicators.

Page 5 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

developmental processes have been adapted to meet OWS timelines, we

analyzed vaccine candidates’ technology readiness levels (TRL) and

reviewed steps vaccine companies took to develop their vaccines. We

used TRLs, a maturity scale ordered according to the required

characteristics of the specific technology, similar to those specified in our

GAO Technology Readiness Assessment Guide.

8

In the case of vaccine

development, HHS provides development process guidelines in its

integrated TRLs for medical countermeasures, which include vaccines.

9

We used the HHS TRLs to compare the OWS vaccine candidates to the

standard vaccine development process. We sent a questionnaire that

reflected HHS’s integrated TRL criteria to all OWS vaccine companies.

We also collected supporting documentation and conducted follow-up

interviews with each company to clarify or further support their responses

to the questionnaire, when necessary. To assign TRLs for each vaccine

candidate, we reviewed questionnaire responses, and supporting

documentation. When necessary, we relied on peer-reviewed studies or

other public information to validate company responses. To describe how

each vaccine company adapted their developmental processes to meet

OWS timelines, we reviewed the supporting documents we collected and

compared them against the OWS timelines. To describe the challenges in

scaling up manufacturing and the steps companies are taking to address

those challenges, we interviewed representatives responsible for

manufacturing-related activities from each of the OWS vaccine

companies, as well as representatives from the vaccine companies’

manufacturing partners.

10

See appendix I for additional information on our

objectives, scope, and methodology.

8

GAO, Technology Readiness Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Evaluating the

Readiness of Technology for Use in Acquisition Programs and Projects, GAO-20-48G

(Washington, D.C.: January 7, 2020).

9

See Department of Health & Human Services. Integrated TRLs for Medical

Countermeasure Products (Drugs and Biologics).

https://www.medicalcountermeasures.gov/trl/integrated-trls/ (accessed December 28,

2020). Medical countermeasures include drugs and biologics, such as vaccines, that can

diagnose, prevent, protect from, or treat the effects of exposure to emerging infectious

diseases, such as pandemic influenza, and to chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear

agents. The scope of this report is limited to vaccines.

10

OWS vaccine companies include Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca, Janssen,

Sanofi/GSK, and Novavax. Manufacturing partners included Emergent Biosolutions and

the Texas A&M Center for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing

(Texas A&M CIADM).

Page 6 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

We conducted this performance audit from July 2020 to February 2021 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

HHS and DOD, in support of OWS, awarded contracts and other

transaction agreements to six vaccine companies to develop or

manufacture vaccine doses.

11

According to the OWS Chief Advisor and

the Director of Vaccines, OWS officials selected vaccine candidates from

four vaccine-platform technologies that OWS considered to be the most

likely to yield a safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19.

12

In

addition, OWS considered whether they met the following three criteria:

13

1. had robust preclinical data or early-stage clinical trial data supporting

their potential for clinical safety and efficacy;

2. had the potential, with OWS acceleration support, to enter large

phase 3 field efficacy trials in July to November 2020 and to deliver

efficacy outcomes by the end of 2020 or the first half of 2021;

3. were based on vaccine-platform technologies permitting fast and

effective manufacturing, with companies demonstrating the industrial

11

Other transaction agreements are flexible agreements that allow the parties to negotiate

terms and conditions specific to the project. Overall, about $8.8 billion of roughly $13

billion dollars for vaccine development and manufacturing have been obligated through

other transaction agreements as of December 31, 2020.

12

A vaccine platform is a technology for production of different vaccine antigens—proteins

or other biomolecules that stimulate the immune response. A protein antigen may be

produced by incorporating a gene that codes for a protein or protein subunit from the

relevant virus or other pathogen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) into another virus called a vector.

The vector serves as a delivery vehicle for the genetic material, which code for the

antigen. Vaccine platforms may have uniform, predictable characteristics, such as safety

effects; however, each antigen in a specific platform will have different immune response

characteristics.

13

See M. Slaoui and M. Hepburn. “Developing Safe and Effective COVID Vaccines —

Operation Warp Speed’s Strategy and Approach,” New England Journal of Medicine, Aug.

26, 2020.

Background

Vaccine Selection Criteria

Page 7 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

process scalability, yields, and consistency necessary to reliably

produce more than 100 million doses by mid-2021.

As of January 2021, five of the six OWS vaccine companies were testing

their vaccine candidates in phase 3 clinical trials. Two vaccines received

emergency use authorizations (EUA) from the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) in December 2020.

14

These vaccines received

EUAs in less than a year from the time the genetic code of SARS-CoV-

2—the virus that causes COVID-19—was sequenced. This was

considerably faster than any previous vaccine development and

authorization for use in the United States.

The traditional process for developing a new vaccine is well established

and tends to be sequential (see figure 2). Although there is sometimes

overlap in phases, a longer, more sequential approach is common in non-

pandemic environments. According to two vaccine companies we met

with, the purpose of this approach is in part to reduce financial risk

because each phase is costly—with later phases being especially

costly—and each phase improves the understanding of whether the next

phase will be successful.

Figure 2: Traditional Vaccine Development Process

Note: The timelines for vaccine development depicted in this figure are not drawn to scale. This

timeline depicts an example, and the specific development steps and timeline for a given vaccine may

vary from this example. There may be some overlap among steps.

14

During an emergency, as declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services

under 21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3(b), FDA may temporarily allow the use of unlicensed COVID-

19 vaccines through an EUA, provided certain statutory criteria are met. For example, a

company requesting an EUA must provide evidence that the vaccine may be effective and

that the known and potential benefits outweigh the known and potential risks, among other

requirements. Any COVID-19 vaccine that initially receives an EUA from FDA is expected

to ultimately be reviewed and receive licensure through a biologics license application,

according to FDA guidance.

Traditional Vaccine

Development Process

Page 8 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

a

Phase 1 clinical trials generally test the safety of a product with a small group of healthy volunteers

(usually fewer than 100). These trials are designed to determine the product’s initial safety profile and

the side effects associated with increasing doses, among other things.

Phase 2 clinical trials are designed to evaluate the effectiveness of a product for a particular use and

determine the common short-term side effects and risks associated with the product. These trials are

conducted with a medium-size population of volunteers (usually a few dozen to hundreds).

Phase 3 clinical trials are performed after preliminary evidence suggesting effectiveness of a product

has been obtained, and are intended to gather additional information about safety and effectiveness.

These trials usually involve several hundred to thousands of volunteers, including participants who

are at increased risk for infection. According to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) officials, these

clinical trial phases may overlap.

b

According to FDA, manufacturing processes are reviewed as part of the vaccine licensure process.

Thus, even under a traditional vaccine timeline, some initial manufacturing occurs during

development, so the manufacturing processes can be adequately validated.

In the exploratory phase, the target and candidate vaccine are

identified.

15

In the preclinical phase, researchers use cells and animals to

assess safety and produce evidence of clinical promise, evaluated by the

candidate’s ability to elicit a protective immune response. During clinical

trials, more human subjects are added at each successive phase. Safety,

efficacy, proposed doses, schedule of immunizations, and method of

delivery are evaluated (see table 1).

Table 1: Typical Phases of Clinical Trials

Phase 1

Determines the product’s initial safety profile and the side effects associated with increasing doses, among

other things. These trials generally test the safety of a product with a small group of healthy volunteers (usually

fewer than 100).

Phase 2

Evaluates the effectiveness of a product for a particular use and determines the short-term side effects and

risks associated with the product. These trials are conducted with a medium-size population of volunteers

(usually a few dozen to hundreds).

Phase 3

Performed after preliminary evidence suggesting effectiveness of a product has been obtained and are

intended to gather additional information about safety and effectiveness. These trials usually involve several

hundred to thousands of volunteers, including participants who are at increased risk for infection.

Source: Food and Drug Administration. | GAO-21-319

Note: According to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) documentation, these clinical trial phases

may overlap. Phase 4 clinical trials may be required after licensure to obtain additional information on

the product’s benefits, risks, and optimal use.

The next phase is FDA review of the biologics license application (BLA)

and licensure, which includes oversight of manufacturing and planning for

15

During vaccine development, virus targets need to be identified to develop a safe and

effective vaccine. In the case of COVID-19 vaccines, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was

identified as the virus target.

Page 9 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

postmarket surveillance.

16

At any phase, the process can be terminated

for various reasons including detection of adverse events, such as

serious side effects.

The federal government uses TRLs to systematically review the progress

of new technologies along a spectrum of technology maturity from basic

research to operational implementation of a proven technology. For

vaccine development, HHS tailored a set of integrated TRLs for medical

countermeasures.

17

Specifically, HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research

and Development Authority (BARDA) uses TRLs to make funding

determinations for vaccines by requesting the information aligning with

the TRL definitions from pharmaceutical companies to report progress on

their research and development (R&D) programs. These TRL criteria

allow a vaccine R&D program to be categorized by its degree of maturity,

from basic research about the mechanisms of a disease to the evaluation

of a vaccine candidate using animal studies and clinical trials in humans,

and finally through licensure and large-scale manufacturing of the

vaccine. We used the HHS integrated TRLs as a metric in this report

because TRLs represent a widely accepted system for tracking

technological progress.

The HHS integrated TRL medical countermeasure scale consists of nine

levels, requiring demonstration that a vaccine has achieved incrementally

higher levels of technical maturity until the final level, where a vaccine has

reached post-FDA licensure activities. See Appendix II for a detailed

description of the HHS integrated TRLs.

The HHS integrated TRLs include the phases of the traditional vaccine

development process (exploratory phase, preclinical phase, clinical trials,

BLA submission, and FDA review and licensure). Figure 3 compares the

HHS integrated TRLs and the traditional vaccine development and

manufacturing processes.

16

Phase 4 clinical trials may be required after licensure to obtain additional information on

the product’s benefits, risks, and optimal use.

17

HHS adapted the TRL format, originally developed by the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration and DOD, to evaluate the development of medical countermeasures

against both natural and man-made public health threats.

HHS Integrated

Technology Readiness

Levels

Page 10 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 3: Department of Health and Human Services’ Integrated Technology Readiness Level (TRL) Countermeasure Scale

and the Traditional Vaccine Development and Manufacturing Processes

a

Potential for FDA authorization for emergency use

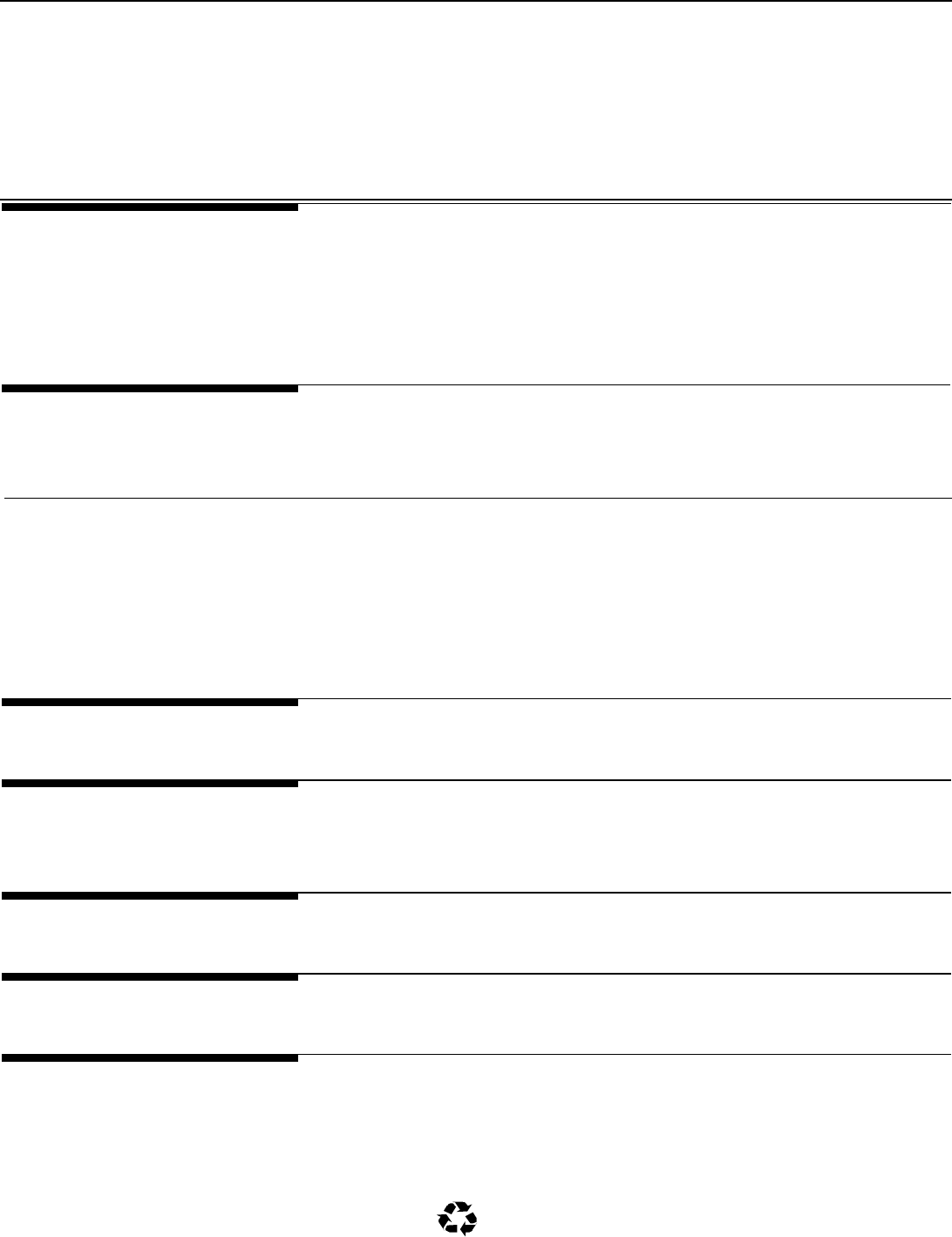

OWS’s strategy for rapid vaccine development was to build a diverse

portfolio of vaccine candidates based on distinct platform technologies.

According to OWS officials, this approach intended to provide a range of

options, potentially accelerating development and mitigating the risks

associated with the challenge of developing a safe and effective vaccine

on OWS’s timelines.

18

OWS officials originally planned to include four

platforms in the OWS vaccine candidate portfolio: messenger RNA

(mRNA), replication-defective live-vector, recombinant-subunit-

adjuvanted protein, and attenuated replicating live vector (see fig. 4).

18

See M. Slaoui and M. Hepburn. “Developing Safe and Effective COVID Vaccines —

Operation Warp Speed’s Strategy and Approach,” New England Journal of Medicine, Aug.

26, 2020.

OWS Supported a

Range of Vaccine

Approaches

To Mitigate Risk, OWS

Supported Vaccines with

Different Characteristics

Page 11 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

OWS has publicly announced support for six vaccine candidates using

three of those platforms.

OWS’s strategy included selecting different platform technologies to

mitigate the risk that any one platform or specific vaccine candidate could

fail because of problems with safety, efficacy, industrial manufacturability,

or scheduling factors. This strategy included two vaccine platforms that

had not previously been used in a licensed vaccine, but could

theoretically be quickly adapted to COVID-19 and scaled up rapidly (i.e.,

mRNA platform and replication-defective live-vector platform), and one

platform that had been proven (i.e., recombinant-subunit-adjuvanted

protein platform).

Page 12 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 4: Overview of the Four Vaccine Platform Technologies Considered by Operation Warp Speed, as of January 2021

Note: Asterisk (*) indicates company has received an emergency use authorization (EUA), which

allows the temporary use of an unlicensed vaccine, provided certain statutory criteria are met. As of

January 2021, phase 3 clinical trials are still ongoing for these COVID-19 vaccine candidates, and the

candidates are expected to ultimately be reviewed and receive licensure through a biologics license

application, according to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance.

Human cells use lock-and-key-style security to allow for the necessary

exchange of proteins while preventing the intrusion of disease-causing

microbes, such as viruses. Before entering a cell, a protein needs to

present a unique ‘key’—a molecular pattern that opens a specific

‘lock.’ Coronaviruses, such as SARS-CoV-2, use counterfeit keys, called

Vaccine Platform

Technologies Utilize

Different Mechanisms

for Stimulating Immune

Responses

Page 13 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

spike “S” proteins, to enter human cells.

19

All COVID-19 vaccines share a

common strategy: teach the immune system to recognize the SARS-CoV-

2 spike protein and neutralize the virus, providing immunity. The immune

system response that neutralizes the virus is largely mediated by antibody

production and associated immune cells (e.g., T cells). The OWS vaccine

candidates differ in what method, or platform, they use to initiate these

immune responses. There are three main platforms: mRNA, replication-

defective live-vector, and recombinant-subunit-adjuvanted protein (see

table 2). These three vaccine platforms, unlike other vaccine platforms,

do not require researchers to grow the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which has

sped the time of development and avoided safety concerns associated

with using a disease-causing virus.

mRNA platform: The Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccines

deliver the genetic sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein directly to

the cell (see fig. 5). The mRNA molecule includes a code that causes the

cell to make the spike protein. Immune system cells recognize the spike

protein and a protective immune response results. The spike protein

genetic code does not enter the cell’s nucleus, only the cytoplasm.

20

The

mRNA needs to be encased in a lipid (fat) nanoparticle to enter the cell.

21

• Pfizer/BioNTech – Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccine, BNT162b2,

consists of mRNA encoding the viral spike protein of SARS-CoV-2,

transported inside lipid nanoparticles that allow the mRNA to enter

cells. The vaccine remains shelf-stable in an ultra-low temperature

freezer between -80°C to -60°C. Vials must be kept frozen between -

80°C to -60°C and protected from light until ready to use. The vaccine

remains shelf-stable for up to five days at standard refrigerator

temperatures (between 2° and 8°C).

• Moderna – Moderna’s mRNA-1273 vaccine also consists of mRNA

encoding the viral spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus transported

in lipid nanoparticles. The Moderna vaccine can be stored at

refrigerator temperatures (between 2° and 8°C) for 30 days, and it is

stable for 6 months during shipping and long-term storage at freezer

temperatures of -20°C.

19

Coronaviruses are a family of related RNA viruses that cause mild to lethal respiratory

tract diseases in mammals and birds. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is the strain

responsible for COVID-19.

20

The nucleus is the inner part of the cell where the cell’s DNA is located while the

cytoplasm is the area outside of the nucleus, but still inside the cell membrane.

21

mRNA is a biological molecule that codes for protein.

Page 14 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 5: The Process for mRNA Vaccines Generating Antibodies to Protect Individuals from COVID-19

Replication-defective live-vector platform: The Janssen and

AstraZeneca vaccine candidates use a weakened adenovirus—a virus

that can cause the common cold but that is altered so that it cannot

reproduce or cause disease. Known as a viral vector, it carries a DNA

code to make the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that will stimulate the

immune system to produce antibodies. The vector interacts with the

target cell and delivers its genetic material into the nucleus, where cellular

enzymes generate the spike protein, but not the adenovirus itself (see fig.

6). The vaccinated person will produce the spike protein, priming their

immune system to target SARS-CoV-2.

• Janssen - Janssen’s vaccine candidate uses a non-replicating human

Adenovirus 26 vector platform, the same platform Janssen used to

develop a vaccine for Ebola. This virus, which normally causes the

common cold, contains the genetic material of the SARS-CoV-2 spike

protein. This vaccine candidate can be stored between 2 and 8°C for

at least three months.

• AstraZeneca - AstraZeneca’s AZD1222 vaccine candidate consists of

a non-replicating chimpanzee adenovirus, ChAdOx1, which is a

weakened version of the virus that causes infections in non-human

primates. This vaccine candidate can be stored between 2 and 8°C.

Page 15 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 6: The Process for Replication-defective Live-vector Vaccines Generating Antibodies to Protect Individuals from

COVID-19

Recombinant-subunit-adjuvanted protein platform: The Sanofi/GSK

and Novavax vaccine candidates use purified SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins

to stimulate an immune response (see fig. 7). Often, recombinant-subunit

adjuvanted protein platforms require an adjuvant, a component of the

vaccine that helps the immune system response. Examples of the

vaccines produced using this platform include Hepatitis B, human

papilloma virus, and tetanus vaccines.

• Sanofi/GSK – Sanofi/GSK’s vaccine candidate, developed in

partnership by Sanofi and GSK, uses the same recombinant protein-

based technology as one of Sanofi’s seasonal influenza vaccines with

GSK’s established pandemic adjuvant technology. This vaccine

candidate can be stored between 2° and 8° C.

• Novavax - Novavax’s NVX-CoV2373 vaccine candidate is a

recombinant nanoparticle spike protein vaccine candidate that

includes a proprietary adjuvant to increase the immune response. It

can be stored between 2° and 8°C.

Page 16 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 7: The Process for Recombinant-subunit-adjuvanted Protein Vaccines Generating Antibodies to Protect Individuals

from COVID-19

Attenuated replicating live-vector platform: This platform uses a

genetically engineered virus with its disease-causing aspects removed.

Once injected, human cells replicate the spike proteins and the virus,

allowing for other cells to be infected and more spike proteins produced,

triggering an immune response. No OWS vaccine candidates are using

this platform.

Table 2 below summarizes key characteristics of each OWS vaccine

candidate.

Page 17 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Table 2: Characteristics for Each Operation Warp Speed Vaccine Candidate, as of January 2021

Vaccine

identifier

Candidate

company

Vaccine

platform

Doses

Dose

spacing

(days)

Mixing

required

a

Storage

temperature

b

BNT162b2

Pfizer/BioNTech

mRNA

c

2

21

Yes

2 to 8°C up to 5 days

Longer periods -80 to -60°C

mRNA-1273

Moderna

mRNA

c

2

28

No

2 to 8°C up to 30 days

Longer periods -25 to -15°C

Ad26.COV2

.S

Janssen

Replication-

defective live-

vector

1

N/A

No

At least 3 months at 2 to 8°C

Up to 2 years at -20°C

AZD1222

AstraZeneca

Replication-

defective live-

vector

2

28

No

2 to 8°C up to 6 months

VAT01

Sanofi/GSK

Recombinant-

subunit-

adjuvanted

protein

2

21

Yes

2 to 8°C

NVX-

CoV2373

Novavax

Recombinant-

subunit-

adjuvanted

protein

2

21

No

2 to 8°C

Source: GAO analysis of information from vaccine companies, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and other government sources. | GAO-21-319.

a

Mixing required means the addition of an adjuvant (to increase immune response) or diluent (to

dilute the vaccine) is required at the time of vaccine administration.

b

Storage temperature is the recommended temperature range for vaccine storage.

c

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

As of January 2021, five of the six OWS vaccine candidates had begun

phase 3 clinical trials in the United States, and two had received an

EUA.

22

In November 2020, we reviewed four of the vaccine candidates’

clinical trial protocols.

23

We found that they generally appeared to follow a

typical clinical trial design by enrolling mostly healthy adults and excluding

such groups as children, pregnant women, and those with certain

22

Companies that have started phase 3 trials in the United States are AstraZeneca,

Janssen, Moderna, Novavax, and Pfizer/BioNTech. In December 2020, FDA authorized

the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines for emergency use.

23

GAO, COVID19: Federal Efforts Accelerate Vaccine and Therapeutic Development, but

More Transparency Needed on Emergency Use Authorizations, GAO-21-207

(Washington, D.C.: Nov. 17, 2020).

Vaccine Clinical

Trials Provide Critical

Information about

Safety and Efficacy

for Populations

Included in the Trials

Page 18 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

comorbid or unstable conditions.

24

Excluding these groups in the initial

phase 3 clinical trials is not unusual, but a potential consequence is that

the data on vaccine safety and effectiveness is based on mostly healthy

adults and may not apply to these excluded populations.

25

The Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee

(VRBPAC) noted that the FDA issuance of EUAs should be used

according to the evidence gathered in the phase 3 clinical trials.

26

The

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee

on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has issued interim recommendations,

including vaccine dosing regimens, age restrictions, and for pregnant and

lactating people.

27

As of January 2021, the vaccines that had received EUAs had not been

licensed by FDA and continue to be studied in clinical trials. For vaccines

that received EUA, additional data on vaccine effectiveness will be

generated from further follow-up of participants in clinical trials already

underway before the EUA was issued. The two EUAs issued in

December 2020 were based on analyses of clinical trial participants and

showed about 95 percent efficacy for each vaccine. These analyses

included assessments of efficacy after individuals were given two doses

of vaccine and from follow-up for a median duration of 2 months to

24

Three of the four companies set a minimum enrollment age of 18 years for their initial

phase 3 clinical trials. The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is authorized for emergency use for

individuals 16 years of age and older. Pfizer/BioNTech recently started trials on volunteers

as young as 12 years old, and Moderna started trials on volunteers ages 12-17.

25

In reviewing EUA requests, FDA considers the intended use of a particular vaccine and

will include a contraindication in product labeling for those groups for which the risk of use

clearly outweighs any benefit, according to agency officials.

26

VRBPAC reviews and evaluates data concerning the safety, effectiveness, and

appropriate use of vaccines and related biological products which are intended for use in

the prevention, treatment, or diagnosis of human diseases, and, as required, any other

products for which the FDA has regulatory responsibility.

27

According to CDC, ACIP provides advice and guidance to the Director of the CDC

regarding use of vaccines and related agents for effective control of vaccine-preventable

diseases in the civilian population of the United States. Recommendations made by the

ACIP are reviewed by the Director, and if adopted, are published as official CDC/Health

and Human Services (HHS) recommendations in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly

Report. According to CDC, people who are pregnant and part of a group recommended to

receive the COVID-19 vaccine may choose to be vaccinated. If they have questions about

getting vaccinated, a discussion with a healthcare provider might help them make an

informed decision. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-

ncov/vaccines/recommendations/pregnancy.html.

Page 19 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

monitor for adverse events. For the two vaccines that received EUAs,

Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, phase 3 clinical trials did not study the

efficacy of a single dose regimen in a manner that allowed for definitive

conclusions, according to FDA.

28

According to FDA, a BLA typically includes safety data from the entire

study population through at least 6 months of follow-up following the last

vaccination, though most adverse events are observed within 1.5 months

of vaccine administration. In clinical trials for the Pfizer/BioNTech and

Moderna vaccines, participants reported side effects such as pain at the

injection site, fatigue, and headache. These side effects are not unusual

for vaccines. The initial phase 3 clinical trials for these vaccines excluded

people with a history of severe adverse reactions to any vaccine or

allergic reactions to any component of this vaccine. More than 20 cases

of suspected anaphylaxis following vaccine administration occurred in the

United States as of January, 2021.

29

FDA issued an EUA fact sheet in

December 2020 (Moderna) and January 2021 (Pfizer/BioNTech) that

stated there is a “remote chance” of a severe allergic reaction and

recommended that people with severe allergic reactions to the first dose

of the vaccine not receive the second dose and people allergic to any of

the vaccine’s ingredients not get the vaccine.

30

The fact sheet also notes

that the two vaccines continue to be studied in additional clinical trials and

that serious and unexpected side effects may occur.

28

According to FDA, as of January 4, 2021, 98 percent of phase 3 trial participants in the

Pfizer/BioNTech trial and 92 percent of participants in the Moderna trial received two

doses of the vaccine at either a three- or four-week interval, respectively. Those

participants who did not receive two vaccine doses at either a three-or four-week interval

were generally only followed for a short period of time. Therefore, FDA determined there is

not enough data to draw conclusions about the depth or duration of protection after a

single dose of vaccine. See See S. Hahn, and P. Marks. Food and Drug Administration:

FDA Statement on Following the Authorized Dosing Schedules for COVID-19 Vaccines,

(Press Release Jan. 4, 2021).

29

In January 2020, CDC reported that the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System

detected 11.1 cases of anaphylaxis per million doses of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine and

2.5 cases of anaphylaxis per million doses of the Moderna vaccine. For both vaccines,

greater than 70-percent of cases of anaphylaxis occurred within 15 minutes of vaccination.

30

Food and Drug Administration, Fact Sheet for Recipients and Caregivers: Emergency

Use Authorization (EUA) of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine to Prevent

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Individuals 16 Years of Age and Older (Revised

January 2021); and Fact Sheet for Recipients and Caregivers: Emergency Use

Authorization (EUA) of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine to Prevent Coronavirus Disease

2019 (COVID-19) in Individuals 18 Years of Age and Older (Revised December 2020).

Page 20 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

The HHS integrated TRLs generally reflect the traditional process used

for vaccine development. Therefore, they provide the measurement

standard by which we can assess the development process to

understand where and how the process may have been modified for

COVID-19 vaccines.

31

In an effort to understand the readiness of each OWS vaccine candidate,

we conducted a TRL analysis, which showed that vaccine companies

generally followed the traditional development process. After reviewing

vaccine companies’ questionnaire responses and supporting information,

we assigned TRLs to each vaccine candidate based on the HHS

integrated TRLs using associated FDA guidance and supporting

documentation for each vaccine candidate. Table 3 shows our assigned

TRL for each of the vaccine candidates as of January 21, 2021.

31

We did not assess the extent to which the development process for OWS vaccine

candidates met criteria for vaccine authorization or licensure set forth in statute and

regulation.

COVID-19 Vaccine

Development

Generally Followed

Traditional Practices,

with Some

Adaptations

Page 21 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Table 3: Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) for Each Operation Warp Speed (OWS) Vaccine Candidate, as of January 2021

Vaccine Company

TRL

Description

Pfizer/BioNTech

8A

Vaccine has achieved completion of current good manufacturing practice (CGMP)

validation and consistency lot manufacturing, and pivotal clinical trials demonstrating

sufficient efficacy and safety to receive an emergency use authorization (EUA).

Moderna

8A

a

Vaccine has achieved completion of CGMP validation and consistency lot

manufacturing, and pivotal clinical trials demonstrating sufficient efficacy and safety to

receive an EUA.

AstraZeneca

7B

Vaccine has achieved scale-up, initiation of CGMP process validation, and expanded

clinical trials as appropriate for the product.

Janssen

7B

a

Vaccine has achieved scale-up, initiation of CGMP process validation, and expanded

clinical trials as appropriate for the product.

Novavax

6C

ab

Vaccine has achieved CGMP pilot lot production, investigational new drug (IND)

application submission, and phase 2 clinical trials that establish an initial safety,

pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity assessment as appropriate.

Sanofi/GSK

6C

a

Vaccine has achieved CGMP pilot lot production, IND application submission, and

phase 1 clinical trials that establish an initial safety, pharmacokinetics, and

immunogenicity assessment as appropriate.

Source: GAO analysis of vaccine companies’ questionnaire responses and vaccine development documentation. I GAO-21-319

Note: GAO assigned these TRLs based on questionnaire responses and documentation, where

available.

CGMP regulations for drugs and biologics, including vaccines, contain minimum requirements for the

methods, facilities, and controls used in manufacturing, processing, and packing of a drug product.

The regulations help to ensure that a product is safe for use, and that it has the ingredients and

strength it claims to have. See 21 C.F.R. pts. 210 and 211 (2020).

An IND is a formal notice to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of a company’s intent to begin

human clinical trials. An IND must include evidence that the product is reasonably safe for proposed

clinical trials, based on preclinical data, among other information. FDA has 30 days to object to an

IND before it becomes effective. 21 C.F.R. pt. 312 (2020).

TRL 8A indicates that additional expanded clinical safety trials may be required for the product. In the

case of a COVID-19 vaccine, we assigned a TRL 8A when an emergency use authorization (EUA)

was issued for that product. During an emergency, as declared by the Secretary of Health and

Human Services under 21 U.S.C. § 360bbb-3(b), FDA may temporarily authorize unapproved medical

products or unapproved uses of approved medical products through an EUA, provided certain

statutory criteria are met. FDA has indicated that issuance of an EUA for a COVID-19 vaccine for

which there is adequate manufacturing information would require the submission of certain clinical

trial information from phase 3 clinical trials that demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of the

vaccine in a clear and compelling manner, among other things. Any COVID-19 vaccine that initially

receives an EUA from FDA is expected to ultimately be reviewed and receive licensure through a

biologics license application, according to FDA guidance.

a

TRL based at least in part on testimonial evidence; GAO could not verify all information supporting

our TRL determination through documentary evidence.

b

Although Novavax is currently conducting phase 3 clinical trials, they reported that as of February 2,

2021, they had not completed the step to scale up and validate the CGMP manufacturing process,

and therefore did not yet meet the criteria for TRL 7.

Page 22 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Each of the OWS vaccine companies we talked to told us that the primary

difference between COVID-19 vaccine development and vaccine

development in a non-pandemic environment was the compressed

timelines under which they were working. In addition, to speed up the

availability of the vaccines, companies initiated large-scale manufacturing

while collecting data on clinical trial participants. In a June 2020 guidance

document, FDA identified some ways that COVID-19 vaccine

development may be accelerated.

32

For example, the guidance document

states that companies may accelerate development by relying on

knowledge gained from similar products manufactured with the same

well-characterized platform technology, to the extent legally and

scientifically permissible. All OWS vaccine companies indicated that prior

experience on the vaccine platform helped support key steps that would

normally be conducted for each individual vaccine.

OWS vaccine companies relied on data from animal studies to develop

COVID-19 vaccines and make adaptations. Although imperfect at

predicting success of a vaccine, animal studies are typically conducted to

improve understanding of whether the vaccine may be safe and effective

in humans before clinical trials begin. We found that all of the companies

performed animal studies to investigate COVID-19 vaccine

immunogenicity—including assessing the neutralizing antibodies and T-

cell responses—and challenge studies that tested the potential for

efficacy in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or COVID-19 in specific

animal models (e.g., mice, hamsters, and/or nonhuman primates).

33

In

addition, all companies indicated that they conducted animal toxicology

studies for their vaccine platform, but some animal studies may not have

been specific to their COVID-19 vaccines. For example, one company

had more than 10 previous animal toxicology studies on the platform they

were using for their COVID-19 vaccine, which showed that there were no

safety concerns from any vaccine made using that platform, and,

therefore, according to the company, it was not necessary to conduct

separate animal studies specific to COVID-19 vaccines to proceed in

developing a vaccine.

32

Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration Center for

Biologics Evaluation and Research, Development and Licensure of Vaccines to Prevent

COVID-19 Guidance for Industry (June, 2020).

33

A challenge study involves vaccinating animals followed by exposing them (i.e.,

challenge) to the SARS-CoV-2 virus and observing if they are protected from COVID-19

disease.

OWS Vaccine Companies

Adapted Some Practices

to Accelerate

Development

Animal Studies Were

Conducted to Inform

Human Studies and Not

All Were Specific to the

OWS Vaccine Candidates

Page 23 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

At least half of the OWS vaccine companies indicated that they had not

completed certain animal safety and efficacy studies before beginning

phase 1 clinical trials.

34

Instead, in order to begin collecting data in clinical

trials more quickly, the companies relied on data from other vaccines

using the same platforms, where available, or conducted animal studies

concurrently with clinical trials. As of January 2021, some animal studies

are still ongoing for COVID-19 vaccines that are in late-stage (e.g., phase

3) clinical trials.

Another approach OWS vaccine companies may have used to enter

clinical trials more quickly was to conduct their pre-clinical studies not in

compliance with good laboratory practices (GLP), which TRL 6 and 7

criteria specify as being needed only “as appropriate.”

35

One company

indicated that GLP safety studies were being conducted for their COVID-

19 vaccine, while others relied on non-GLP studies or GLP studies for

other vaccines using that platform. One company told us that GLP

efficacy studies were not possible for COVID-19 due to limitations of

resources necessary to conduct such studies at the required biological

safety level.

By conducting different phases of clinical trials concurrently (e.g., phase 3

clinical trials beginning as phase 1 trials are ongoing), OWS vaccine

companies increased the speed of the vaccine development process.

36

One company noted that using efficient clinical trial strategies, such as

concurrent or overlapping trials, is particularly important to quickly

determine disease protection (i.e., vaccine efficacy) in a pandemic. For

instance, this approach was successfully used during the Ebola epidemic

in Africa where vaccine efficacy was assessed while the epidemic was

still ongoing. Though some overlap of phases is not unusual even in

traditional vaccine development, officials from two companies stated that

in non-pandemic environments it can take months to review clinical trial

data before starting a new phase. For example, officials from one

company said they might normally take 6 months to review data from

34

FDA recommends that vaccine manufacturers engage in early communications with

FDA to discuss the type and extent of nonclinical testing required for the particular

COVID-19 vaccine candidate to support proceeding to first in human clinical trials and

further clinical development.

35

GLPs define the requirements to ensure data quality and integrity of preclinical research.

See 21 C.F.R. pt. 58 (2020).

36

According to HHS, working on clinical trial phases in parallel instead of taking the

traditional sequential approach to vaccine development potentially shaves months off the

timeline for vaccine development.

OWS Vaccine Companies

Conducted Concurrent or

Combined Clinical Trials

Page 24 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

phase 2 trials before initiating a phase 3 trial, and they would have a

meeting with FDA about the plan before proceeding. For COVID-19

vaccine development, officials from this particular company said they took

3 weeks to review data and initiate efforts to move to phase 3 trials. All six

OWS vaccine companies gathered initial human safety and

immunogenicity data in phase 1 or combined phase 1/2 clinical trials with

a small number of participants before proceeding into trials with more

participants, namely large-scale phase 3 clinical trials, consistent with

traditional processes. All companies that have started phase 3 clinical

trials as of January 2021 did so before completing phase 1 clinical trials

(see fig. 8).

Page 25 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

Figure 8: Operation Warp Speed Vaccine Candidates’ Clinical Trials Schedule as Shown on the clinicaltrials.gov Website as of

January 30, 2021

Note: Clinical trials were listed only if they were sponsored by an Operation Warp Speed company or

a collaborator and were specifically for the Operation Warp Speed vaccine candidate. Dates are

study start dates and completion dates; some dates are estimates. Some of these clinical trials may

not necessarily inform regulatory decisions in the United States.

At least half of the OWS vaccine companies selected a dose for phase 1

clinical trials that was based in part on disease protection data generated

in animal studies for that vaccine candidate or from studies for other

vaccines using the same vaccine platform. One company noted that the

public health emergency precluded them from taking the time to

determine the minimum effective dose. Instead, they focused on a dose

that resulted in an acceptable tolerability and immunogenicity profile and

Page 26 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

with the greatest chance of efficacy. This company recognized that they

might end up delivering a higher dose than is necessary in the short-term,

but indicated they could explore a minimal dose that may be as effective,

but more efficient, at a later time.

As we reported in November 2020, OWS vaccine companies face several

challenges with rapidly scaling up manufacturing operations to produce

hundreds of millions of doses of COVID-19 vaccines, including:

37

• Limited manufacturing capacity. Before the COVID-19 pandemic,

most existing vaccine manufacturing capacity was already in use,

according to experts we interviewed. Therefore, new capacity has

been created, or production capacity shifted from other products.

According to one company representative, vaccine manufacturing is

highly complex and generally will ramp up at a graduated pace, rather

than starting at full-scale. Additionally, once bulk quantities of

vaccines are produced, they must be sealed into sterile containers,

such as vials or syringes, in a process known as fill-finish

manufacturing. We heard from representatives from three

pharmaceutical industry groups we interviewed that there was a

shortage of facilities with capacity to handle fill-finish manufacturing.

That type of facilities shortage can lead to production bottlenecks.

• Disruptions to manufacturing supply chains. Vaccine

manufacturing supply chains have been strained by disruptions

caused by the global pandemic, including changes in the labor

37

In our November 2020 report, we also reported on the difficulty associated with the

technology transfer process for scaling up vaccine manufacturing. We did not include

additional information on that challenge in this report because many vaccine companies

we interviewed reported completing technology transfers at their large-scale

manufacturing facilities.

OWS Vaccine

Companies Face

Challenges to Scaling

Up Manufacturing

and Are Taking Steps

to Help Mitigate

Those Challenges

Several Challenges Hinder

Efforts to Rapidly Scale Up

Vaccine Manufacturing

Page 27 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

market, increases or decreases in the demand for certain goods, or as

one DOD official noted, export restrictions implemented by some

countries. For example, we heard from representatives at one facility

manufacturing COVID-19 vaccines that they experienced challenges

obtaining materials, including disposable reactor bags, reagents, and

certain chemicals. They also said that, due to global demand, they

waited 4 to 12 weeks for items that before the pandemic were typically

available for shipment within one week. We also heard from one

expert we interviewed that the supply of the materials used in fill-finish

manufacturing, such as glass vials and pre-filled syringes, was limited.

• Gaps in available workforce. The ability to hire and train personnel

with the specialized skills needed to run vaccine manufacturing

processes can be a challenge for even experienced manufacturers.

For example, we heard from representatives at a facility

manufacturing COVID-19 vaccines that filling open positions for mid-

to upper management had been a challenge. These positions are

significant because manufacturing managers function as the technical

points of contact for production questions and are responsible for

managing safety, quality, and compliance with CGMPs.

Federal officials and representatives from OWS vaccine companies

described the ways that they are working together to mitigate

manufacturing challenges, and as of January 2021, five of the six

companies had started large-scale manufacturing. OWS officials reported

that 63.7 million doses of vaccines were released to the federal

government as of January 31, 2020. This represents about 32 percent of

the 200 million doses, that according to OWS, the companies with EUAs

are contracted to provide by March 31, 2021.

38

Additional doses of

vaccines are being manufactured, but will not be releasable to the federal

government unless they are authorized for emergency use, OWS officials

reported. Companies reported that they are continuing to work with their

manufacturing partners to ramp up vaccine production as they also work

with OWS to address manufacturing challenges. For example:

• Limited manufacturing capacity. Some companies are working to

expand production capacity. Representatives from one OWS vaccine

company told us that BARDA helped them identify an additional

manufacturing partner to increase production of their vaccine. The

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is also overseeing construction

projects to expand capacity at vaccine manufacturing facilities. For

38

As noted above, FDA authorized the Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines for

emergency use in December 2020.

OWS Vaccine Companies

Are Working with the

Federal Government to

Help Mitigate

Manufacturing Challenges

Page 28 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

example, OWS officials told us in November 2020 that the Corps of

Engineers provided a site assessment and oversight for a

construction project that provided a manufacturing site with two

additional vaccine production suites. According to OWS, the Corps of

Engineers is also overseeing seven agreements to expand

manufacturing capacity, including support to companies that are

manufacturing products such as cell culture media and glass vials.

• Disruptions to manufacturing supply chains. As we reported in

November 2020, representatives from a facility manufacturing COVID-

19 vaccines told us that they were in frequent communication with

OWS officials to coordinate on possible manufacturing disruptions and

that DOD assisted them with expediting procurement and delivery of

critical manufacturing equipment. Additionally, officials from BARDA

said that their subject matter experts in developing and manufacturing

vaccines worked with each of the six OWS vaccine companies to

create a list of critical supply needs that are common across the six

vaccine candidates. To address these critical supply needs, DOD and

HHS officials said that as of December 2020 they had placed

prioritized ratings on 18 supply contracts for vaccine companies under

the Defense Production Act.

39

Furthermore, OWS officials stated that

they have worked with U.S. Customs and Border Protection to

expedite necessary equipment and goods coming into the United

States.

• Gaps in available workforce. OWS officials stated that they have

worked with the Department of State to expedite visa approval

supporting the arrival of key technical personnel, including technicians

and engineers to assist with installing, testing, and certifying critical

equipment manufactured overseas. OWS officials also stated that

they requested that 16 DOD personnel be detailed to serve as quality

control staff at two vaccine manufacturing sites until the organizations

can hire the required personnel. According to OWS, the DOD

personnel were still in place at the manufacturing sites as of January

2021.

39

The Defense Production Act, as delegated, generally provides federal agencies authority

to, among other things, place priority ratings on contracts so that they receive priority

treatment over any other unrated contracts or orders if necessary to meet the delivery or

performance dates specified in the order. See Pub. L. No. 81-774, 64 Stat.798 (1950)

(codified, as amended, at 50 U.S.C. § 4501, et seq.); Exec. Order No. 13,603, 77 Fed.

Reg. 16,651 (Mar. 22, 2012); 15 C.F.R. pt. 700, Sch. 1. For additional information on

agencies’ use of this authority, see GAO, Defense Production Act: Opportunities Exist to

Increase Transparency and Identify Future Actions to Mitigate Medical Supply Chain

Issues, GAO-21-108 (Washington, D.C.: Nov 19, 2020).

Page 29 GAO-21-319 Operation Warp Speed

We provided a draft of this report for review and comment to DOD and