www.penalreform.org

The abolition of the death penalty and its

alternative sanction in Eastern Europe:

Belarus, Russia and Ukraine

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 1

Contents

Acknowledgments 2

Acronyms 3

Introduction 4

Research methodology 5

Executive summary 6

Country-by-country analysis

Republic of Belarus 8

Russian Federation 26

Ukraine 40

Comparison of the application and implementation of the death penalty

and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe 51

2 Penal Reform International

Acknowledgements

This research paper has been created by Penal Reform International (PRI). It was written by Viktoria Sergeyeva

and Alla Pokras, and edited by Jacqueline Macalesher. This report is based on national research papers

prepared by Irina Kuchvalskaya and Vladimir Khomich (Belarus), Oleg Lysyagin (Russia) and Irina Yakovets

(Ukraine).

This research paper has been produced in conjunction with Penal Reform International’s project “Progressive

Abolition of the Death Penalty and Alternatives that Respect International Human Rights Standards” with

the nancial assistance of the European Union under the European Instrument for Democracy and Human

Rights (EIDHR) as well as the nancial assistance of the Government of the United Kingdom (Department for

International Development).

The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of Penal Reform International and can in no

circumstances be regarded as reecting the position of the European Union or the Government of the United

Kingdom.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 3

Acronyms

CAT Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

CPT European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or

Punishment

CRC

Convention on the Rights of the Child

ECHR European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

EIDHR European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights

EU European Union

FSIN

Federal Service of Execution of Punishments of Russia

GA General Assembly

ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

NGO Non-Governmental Organisation

NPM National Preventive Mechanism

ODIHR Ofce for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

OPCAT Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

or Punishment

OSCE

Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

PACE Parliamentary Assembly for the Council of Europe

PED Department of Execution of Punishments of the Belarusian Ministry of Internal Affairs

PRI Penal Reform International

POC Public Oversight Commission (Russia)

SPS State Penitentiary Service (Ukraine)

TB Tuberculosis

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UPR Universal Periodic Review

USA United States of America

4 Penal Reform International

Introduction

The death penalty is the ultimate cruel, inhuman and

degrading punishment. It represents an unacceptable

denial of human dignity and integrity. It is irrevocable,

and where criminal justice systems are open to error

or discrimination, the death penalty will inevitably be

inicted on the innocent. In many countries that retain

the death penalty there is a wide scope of application

which does not meet the minimum safeguards,

and prisoners on death row are often detained in

conditions which cause physical and/or mental

suffering.

The challenges within the criminal justice system do

not end with the institution of a moratorium or with

abolition. Many countries that institute moratoria

do not create humane conditions for prisoners held

indenitely on ‘death row’, or substitute alternative

sanctions that amount to torture or cruel, inhuman

or degrading punishment, such as life imprisonment

without the possibility of parole, solitary connement

for long and indeterminate periods of time, and

inadequate basic physical or medical provisions.

Punitive conditions of detention and less favourable

treatment are prevalent for reprieved death row

prisoners. Such practices fall outside international

minimum standards, including those established

under the EU Guidelines on the Death Penalty.

This research paper focuses on the application of

the death penalty and its alternative sanction in

three countries of Eastern Europe: the Republic of

Belarus, the Russian Federation and Ukraine. Its

aim is to provide up-to-date information about the

laws and practices relating to the application of the

death penalty in this region, including an analysis

of the alternative sanctions to the death penalty

and whether they reect international human rights

standards and norms.

This paper takes a country-by-country approach and

focuses on:

The legal framework of the death penalty and its

alternative sanction (life imprisonment).

Implementation of both sentences, including

information on fair trial standards.

Application of the sentence, including an analysis

of the method of execution, the prison regime and

conditions of imprisonment.

Statistical information on the application of the

death penalty/life imprisonment.

Criminal justice reform processes in general.

This paper provides detailed and practical

recommendations tailored to each country to bring it

in line with international human rights standards and

norms.

We hope this research paper will assist advocacy

efforts towards abolition of the death penalty and

the implementation of humane alternative sanctions

in the region. We hope this paper will be of use to

researchers, academics, members of the international

and donor community, and all other stakeholders

involved in penal reform processes including

government ofcials, parliamentarians, prison ofcials

and members of the judiciary.

March 2012

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 5

Research methodology

Access to information on the application of the

death penalty and its alternative sanction is often

unavailable or inaccurate in many countries.

Statistical information is not always made available

by state bodies, and information provided is not

always timely, or lacks clarity. Across the Eastern

European region in particular, such information is

often classied as a state secret. As such, although

PRI aimed to undertake an in-depth analysis of legal,

policy and practice areas within the remit of this

research paper, access to some information was

beyond the abilities of the researchers, and therefore

gaps in the research remain.

A research questionnaire was designed in late 2010 to

assist researchers in identifying relevant information.

The research questionnaire was designed by PRI

in partnership with Sandra Babcock (Northwestern

University, USA) and Dirk van Zyl Smit (Nottingham

University, UK).

The researchers looked at primary sources, such

as legislation and case law, as well as interviewed

relevant government ofcials within the various

departments of the Ministries of the Interior, the

Ministries of Justice, Constitutional Councils, and

the Penitentiary Services, as well as with national

human rights commissions/Ombudsmen, lawyers

and judges, journalists, and members of civil society/

human rights defenders in all three countries, and

with a cross-section of death row and life sentenced

prisoners where access was made available. The

researchers also turned to reports by individuals or

organisations with rst-hand experience, such as by

inter-governmental organisations including reports by

UN treaty bodies, the OSCE and Council of Europe,

as well as reports by international NGOs such as

Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, Death

Penalty Worldwide and the World Coalition against

the Death Penalty. Reports and articles by journalists

and academics were also analysed.

The research was completed in January 2012.

6 Penal Reform International

Executive Summary

The Eastern European region presents a unique

picture of a region in various stages of the abolition

process: Ukraine has abolished the death penalty

for all crimes in law, Russia is abolitionist in practice,

and Belarus continues to carry out executions.

While Belarus and Russia are the last two countries

in Europe to abolish the death penalty in law, it is

important to note that both of their constitutions

emphasise the exceptional and temporary nature of

this punishment.

Belarus is the only country in Europe that continues

to execute. The last executions took place in March

2012. The death penalty is retained for 14 criminal

offences (12 in time of peace and two in time of war).

However, since 1989, it has almost always been

applied for aggravated murder. According to the

Ministry of Internal Affairs, between 1998 and 2010,

102 men have been sentenced to death in Belarus.

Over the last ten years, the government have made a

number of positive statements in various national and

international forums indicating that Belarus is moving

towards a position of moratorium. A governmental

Working Group on the death penalty was established

in February 2010 to facilitate wide discussions on the

issue of abolition. However, following the disputed

presidential elections in December 2010, discussions

towards a moratorium have stalled. The 2011 terrorist

attack on the Minsk underground has also resulted

in a more negative approach towards establishing

an ofcial moratorium. It is important to note that

politicians in Belarus continue to rely on perceived

public opinion as an argument for retaining the death

penalty. In particular, politicians rely on the results of

a 1996 public referendum according to which 80.44

percent of the public were against abolition.

It should be noted that in the last ten years, the

number of executions have decreased considerably

in Belarus, from 47 executions in 1998, to an

average of two per year since 2008. However, the

total secrecy surrounding the procedures relating to

the implementation of the death penalty, awed fair

trial procedures and the harsh prison conditions for

those on death row raise fundamental human rights

concerns regarding its continued use.

Life imprisonment was established as a new sanction

for 14 criminal offences (the same offences as for

the death penalty) in Belarus is 1997. At least 144

men have been sentenced to life imprisonment since

its introduction, and a further 156 death sentences

have been commuted to life imprisonment. Life

imprisonment does not have a maximum tariff

however that sentence may be substituted for

a denite term of imprisonment after serving a

minimum of 20 years in prison. To date no lifers have

been paroled since life imprisonment has only been in

place for the last fteen years.

While Russia retains the death penalty in its Criminal

Code for ve offences, an ofcial moratorium on both

sentencing and executions has been in place since

February 1999, when the Constitutional Court found

that the death penalty would be unconstitutional until

jury-trials were established in all 89 regions of the

Russian Federation. The moratorium was extended

by the State Duma in 2006 until 2010. Chechnya was

the nal region to establish jury trials in 2010, and in

anticipation of this, the Constitutional Court extended

the moratorium indenitely in November 2009

until Russia raties Protocol No. 6 to the European

Convention on Human Rights.

Executions have not been carried out in Russia

since September 1996 (although executions were

carried out until 1999 in Chechnya, which de

facto was not then under control of the Russian

Federation), and despite the clear direction set

out by the Constitutional Court, debates on the

reinstatement of the death penalty occasionally

resurface. The issue of retaining the death penalty

for those convicted of committing acts of terrorism

has received signicant public coverage following

the Moscow Metro bombings in March 2010 and the

Moscow Domodedovo Airport bombing in January

2011. Furthermore, like Belarus, public opinion on

the death penalty has been an important part of its

continued retention, and law makers continue to refer

to the high percentage of the public who are against

abolition.

Life imprisonment as an alternative to the death

penalty was established by the Russian Federation

in 1992, and in 1996 it was established as a stand-

alone punishment for 13 offences in the Criminal

Code. At least 1,780 men have been sentenced

to life imprisonment since its introduction. Life

imprisonment does not have a maximum tariff;

however a lifer may apply for parole after serving a

minimum of 25 years in prison. To date no lifers have

been paroled.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 7

Ukraine is the only country in the region to have

abolished the death penalty in law for all crimes.

Following its membership to the Council of Europe in

1995, Ukraine promised to abolish the death penalty,

however executions continued until a moratorium

on executions was established on 11 March 1997.

Death sentences continued to be handed down until

the Constitutional Court ruled the death penalty to be

unconstitutional in December 1999 and the President

of Ukraine signed a law abolishing all 24 death

penalty applicable offences from the Criminal Code

in February 2000. Following the abolition of the death

penalty, a new sanction of life imprisonment was

established in 2000, and all 612 death row prisoners

had their sentences commuted to life sentences.

Life imprisonment may be imposed for nine offences

as set out in the Criminal Code, and unlike Belarus

and Russia, women can be sentenced to life

imprisonment in Ukraine. At least 1,883 prisoners are

currently serving a life sentence in Ukraine, including

approximately 20 women. Life imprisonment in Ukraine

does not have a maximum tariff; however a lifer may

apply to the President for a pardon of his/her life

sentence after serving a minimum of 20 years. If the

President grants a pardon, the life sentence is replaced

with a determinate term of 25 years imprisonment.

A prisoner may then apply for parole after serving

a minimum of three-quarters of their sentence.

However, the law is unclear as to whether the 25 year

determinate term includes the 20 years already served,

or whether the 25 years must be served in addition

to the rst 20 years. As such, there is a lack of clarity

as to when the three-quarter minimum term will be

reached by the prisoner. It should be noted that no lifer

has been paroled in Ukraine since life imprisonment

was introduced.

Across the region, all three countries have growing life

populations, and sentences that can be characterised

as disproportionate in length and overly punitive in

nature. People are sentenced after proceedings which

fail to meet international standards for a fair trial

as guaranteed under article 14 of the International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to

which all three countries are state parties. Although

the right to a fair trial is not impeded by a lack of

legal guarantees, it is impeded in practice. The two

fundamental problems across all three countries lie in

the fact that the judiciary is overly inuenced by the

executive and lacks independence; and secondly, the

quality of legal defence, and in particular legal aid, is

poor and under-resourced. This results in notoriously

low acquittal rates and raises questions over the

fairness of sentences handed down, in particular,

death sentences issued in Belarus.

A harsh and discriminatory prison regime, and

a lack of rehabilitation for life or long-term

prisoners, reinforces the punitive

1

nature of life

imprisonment. Prison conditions across the region

are far below international standards. Improvements

are desperately needed to be made in terms of

accommodation, nutrition, sanitation, access to

medical and psychological care, visitation rights,

sentence planning, and rehabilitation and social

reintegration programmes including work and

education programmes. Life and long-term prisoners

are often separated from the rest of the prison

population and kept under a much harsher and

stricter regime–including solitary connement and

semi-isolation–which is unrelated to prison security,

but based on their legal status as lifers.

In Belarus, there is no ofcial information regarding

the treatment and conditions of prisoners on death

row, however, reports indicate that conditions are

poor and that death row prisoners are not provided

with fundamental legal safeguards. Independent

monitoring of places of detention is also severely

lacking across all three countries, and only Ukraine

has ratied the Optional Protocol to the Convention

against Torture (OPCAT), although it has yet to

designate its National Preventive Mechanism (NPM).

1 While the purpose of sentencing is ultimately punitive, the nature of the sentence should be proportionate to the seriousness of the offence and individualised

to the specificities of the crime, including the circumstances in which it was committed. Sentences should not, therefore, be used to serve wider political

purposes or purely to punish the offender. Effectively locking away criminals for life and creating a discriminatory and arbitrary regime purely because of the

type of sentence a prisoner is serving fails to tackle the structural roots of crime and violence. Prisoners serving life or long-term imprisonment often experience

differential treatment and worse conditions of detention compared to other categories of prisoner. Examples include separation from the rest of the prison

population, inadequate living facilities, excessive use of handcuffing, prohibition of communication with other prisoners and/or their families, inadequate health

facilities, extended use of solitary confinement and limited visit entitlements. Punitive conditions of detention and less favourable treatment are known to be

particularly prevalent for reprieved death row prisoners. Sentences should reflect international human rights standards and norms, and provide the offender with a

meaningful opportunity for rehabilitation and reintegration back into society, thereby leading to law-abiding and self-supporting lives after their release.

8 Penal Reform International

Republic of Belarus

I Basic country information

Geographical region: The Republic of Belarus is the

biggest landlocked country in Europe. It is situated

in Eastern Europe and bordered by Russia, Ukraine,

Poland, Lithuania and Latvia. The capital is Minsk.

Type of government: According to Article 1 of the

Constitution, the Republic of Belarus is a unitary,

democratic, social state. Belarus is governed by a

President and a National Assembly.

Language: The ofcial state languages are Belarusian

and Russian.

Population: According to the 2009 census, the

population of Belarus is 9.5 million people

2

composed

of about 130 nationalities and ethnic groups.

Belarusians account for the majority, with Russians,

Poles and Ukrainians make up the majority of the

minority.

Religion: The majority of Belarusians are Orthodox

Christians.

II Overview of the status of the

death penalty in Belarus

In 1928, the Criminal Code of the Belarusian Soviet

Socialist Republic applied the death penalty to 60

different offences. Although, the 1960 Criminal Code

greatly decreased this number, it remained high at

more than 30 offences. An important point is that

both Codes, like the Constitution, emphasised that

the death penalty was only a temporary measure.

Article 24 of the Constitution of the Republic of

Belarus states, “until its abolition, the death penalty

may be applied in accordance with law as an

exceptional measure of punishment for especially

grave crimes and only in accordance with a court

sentence” (emphasis added).

The reduction in the scope of application of the death

penalty happened in parallel with an increase in the

categories of people exempt from the application of

the death penalty. Under the 1960 Criminal Code,

those under the age of 18 at the time the offence was

committed, and pregnant women were prohibited

from being sentenced to death. An amendment

was made on 1 March 1994 which extended the

categories prohibited from a death sentence for

women entirely.

Belarus’ Criminal Code adopted on 9 July 1999, and

entered into force on 1 January 2001, reduced the

number of death penalty applicable crimes to 14

offences (12 in time of peace and two in time of war),

and exempt from this form of punishment those over

the age of 65 at the time of sentencing.

The death penalty continues to be applied in Belarus,

making it the only country in Europe that carries

out executions. The last two executions were in

March 2012. It should be noted that the number of

executions has decreased dramatically in the last ten

years, from 47 executions in 1998, to an average of

two per year since 2008.

One of the key arguments in favour of its retention is

its alleged strong public support. On 24 November

1996 a public referendum was carried out on the

question of the death penalty in Belarus. 80.44

percent of those polled were against abolition.

Opinion polls carried out in 2000 and 2003

demonstrated that approximately 70 percent of the

population were still in favour of the death penalty.

However, data obtained in 2008 from a national poll,

carried out by the research centre ‘NOVAK’, showed

that 48.2 percent of those polled were in favour of the

death penalty, and 39.2 percent were in support of

abolition. It should be noted that the general public

are not given full information about the effect and

efcacy of the death penalty in practice, which can

have a negative impact on the outcome of public

opinion.

Over the last ten years, the government have made a

number of positive statements in various national and

international forums indicating that Belarus is moving

towards a position of moratorium.

In May 2002, parliamentary hearings on the political

and legal aspects of the death penalty were

organised by the House of Representatives of the

National Assembly (the lower house of parliament).

This represented a serious step forward on the road

to debating the question of abolition in Belarus. The

2 Belarusian National Committee of Statistics, <http://belstat.gov.by/homep/ru/perepic/2009/itogi1.php>.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 9

House of Representatives recommended that the

Belarusian cabinet of ministers study the issue of the

death penalty based on the possibility of gradually

introducing a moratorium. This recommendation

indicated a willingness of the Belarusian state

legislature to adopt a positive approach to abolition.

Following a request from the House of

Representatives, the Constitutional Court considered

whether the death penalty was constitutional in

March 2004. The Court recalled amendments made

to the 1999 Criminal Code in order to bring national

legislation in line with international standards

prevailing in the area of application of the death

penalty. It also made specic reference to the

importance of the 1996 referendum in the retention

of the death penalty. However the Court paid

particular attention to Article 24(3) of the Constitution

which permits the application of the death penalty

while emphasising the exceptional and temporary

nature of this punishment, and subsequently ruled

3

that a number of provisions of the Criminal Code

were inconsistent with the Constitution due to their

lack of reference to the temporary nature of the

death penalty.

4

The Court’s ruling providing for the

possibility of either the abolition of the death penalty

or the imposition of a moratorium on executions as

a rst step towards full abolition. However, the Court

ruled that such measures may only be enacted by the

head of state and the Parliament

The recommendations of the Constitutional Court

were welcomed in 2005 by the Special Rapporteur

on the situation of human rights in Belarus,

5

who

encouraged the government to abolish the death

penalty in law, or, as a rst step, to introduce a

moratorium.

However, instead of taking these recommendations

forward by abolishing the death penalty, the President

submitted a draft law to parliament in June 2005

that, inter alia, supplemented the Criminal Code with

a reference to the temporary nature of the death

penalty, which, until its abolition, may be applied as

an exceptional measure for cases of premeditated

murder with aggravating circumstances. On 23 June

2006, the law was adopted by the Parliament.

Neither the President nor the Parliament took any

further steps towards a moratorium, however, in June

2009 the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council

of Europe (PACE) voted in resolution 1671 that

they would restore Belarus’ special guest status in

the Assembly if they would implement an ofcial

moratorium on the death penalty (Belarus’ status was

removed in 1997).

6

Following the adoption of resolution 1671, Belarusian

high-ranking ofcials and independent experts

expressed their opinion that a moratorium could

be introduced in the near future, not only as a step

towards gaining special guest status in PACE, but

also because public opinion had shifted since the

1996 referendum took place.

7

In July 2009, a Belarusian representative of

government stated at an OSCE Permanent Council

Meeting that “in Belarus, too, there is a movement in

favour of gradually limiting the application of (capital)

punishment” and that “the Belarusian authorities and,

in particular, the national parliament are continuing

to give this subject the attention it deserves in order

to gradually pave the way for an examination of the

possibility of introducing a moratorium on the death

penalty.”

8

In November 2009, the President announced a

special information campaign aimed at the issue

of abolition of the death penalty, stating “[w]e are

planning to conduct a number of events in Belarus

aimed to change public attitude towards the death

penalty.”

9

However the ofcial campaign was

conducted very formally and did not attract public

interest.

3 Decision No. 3–171/2004, Constitutional Court of the Republic of Belarus, 11 March 2004.

4 Articles 48(1)(11) and 50 of the Criminal Code were found to be inconsistent with the Constitution.

5 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus (Mr. Adrian Severin), 18 March 2005, E/CN.4/2005/35, para. 85.

6 Resolution 1671 (2009) Situation in Belarus, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 23 June 2009.

7 Belarusian authorities will go to a moratorium on death penalty, NewsBY.org, 1 July 2009, <http://newsby.org/by/2009/07/01/text8425.htm>.

8 OSCE Permanent Council Meeting, Statement by the Republic of Belarus, Vienna, 20 July 2009, PC.DEL/656/09.

9 Belarus takes steps towards abolition of the death penalty, In Victory, <http://news.invictory.org/issue26466.html>.

10 Penal Reform International

In February 2010, a parliamentary working group on

“the discussion of the death issue” was established.

The working group comprised members of both

chambers of the Belarusian parliament. Nikolay

Samoseiko, the head of the Standing Parliamentary

Commission on Legislation, became the chairperson

of this Working Group.

One of the group’s aims was to facilitate wide

public discussion on the issue of abolition. It was

anticipated that the work of the group would result

in parliamentary hearings on the application of the

death penalty in practice. However, shortly after

its establishment, Belarus executed two men in

March 2010. PACE subsequently suspended high-

level contacts with the Belarusian parliament and

governmental authorities, noting a “lack of progress

towards the standards of the Council and a lack of

political will to adhere to its values”.

10

On 12 May 2010, during the Universal Periodic

Review of Belarus, 15 States raised the question

of the death penalty; 14 recommended ending

its practice and 13 to introduce an immediate

moratorium on executions. Belarus, however, rejected

all of these recommendations.

11

In September 2010, the government of Belarus

did acknowledge to the UN Human Rights Council

the need to abolish the death penalty and stated

its intention to mould public opinion in favour of

abolition, as well as to continue its co-operation with

the international community on this issue.

12

Shortly

after, on 6 December 2010, at the fourth All Belarus

People’s Assembly, President Lukashenko stated that

“the issue of capital punishment should be revisited”,

as there are “strong [arguments] for the non-use of

capital punishment.” At the same time, he stated that

public opinion in favour of capital punishment should

be taken into account.

13

However, following the disputed presidential elections

on 19 December 2010, President Lukashenko ceased

all activities of the governmental working group and

discussion towards a moratorium stalled. This was

due in two parts: rstly, to the negative reaction of

European countries to the presidential elections,

and secondly, the terrorist attack on the Minsk

underground on 11 April 2011. The Chairman of the

Standing Committee on Legislation and Judicial

Issues (and Chair of the death penalty Working

Group), Nikolay Samoseiko, stated that if the April

2011 terrorist had not occurred, a moratorium could

have been discussed in 2011.

14

Two men, Dzmitry

Kanavalau and Uladzislau Kavalyou, accused of

committing the 2011 bomb attack were sentenced to

death by the Supreme Court in November 2011, and

executed in March 2012.

III Legal framework: application

of international human rights

standards in Belarus

According to Article 8 of the Constitution “Belarus

shall recognise the supremacy of the generally

recognised principles of international law and shall

ensure the compliance of laws therewith”. However,

treaties that contradict the Constitution cannot be

ratied.

15

Belarus is party to a number of international human

rights instruments that are relevant to the death

penalty.

Belarus ratied the International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights (ICCPR) on 12 November 1973,

and the First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR on 19

December 1996, however is not a signatory to the

Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR (aiming at

the abolition of the death penalty). Belarus ratied

the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel and

Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) on 13

March 1987, but is not a signatory to its Optional

Protocol (OPCAT). It ratied the Convention on the

Rights of the Child (CRC) on 1 October 1990. It is not

a signatory to the Rome Statute on the International

10 PACE suspends it high-level contacts with the Belarusian Government and Parliament, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 29 April 2010.

11 Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review on Belarus, 21 June 2010, A/HRC/15/16.

12 Country entry on Belarus, Annual Report 2011: The state of the world’s human rights, Amnesty International, 2010.

13 Lukashenko urges a revisiting of the death penalty issue, BelTA, 6 December 2010, <http://news.belta.by/en/news/president?id=598428>.

14 Interview on Euroradio, 13 December 2011, <http://euroradio.fm/ru/report/samoseiko-esli-ne-terakt-my-uzhe-obsuzhdali-moratorii-na-kazn-81829>.

15 Article 8 of the Constitution.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 11

Criminal Court. Belarus is not a party to the European

Convention on Human Rights, or its related Protocols.

Belarus abstained from voting in the three United

Nations General Assembly resolutions calling for a

moratorium on the death penalty in 2007 (resolution

62/149), 2008 (resolution 63/168) and 2010 (resolution

65/206).

IV Legal framework: the death

penalty in Belarus

Death penalty applicable crimes

The Criminal Code, which was adopted on 9 July

1999 and came into force on 1 January 2001,

provides for the death penalty as an exceptional

measure of punishment for particularly serious crimes

involving the deliberate deprivation of life under

aggravating circumstances. Twelve articles specify

the offences for which the death penalty may be

imposed in peace-time and a further two in time of

war:

1. Initiation or waging of aggressive war: Article

122(2).

2. Act of terrorism against a representative of a

foreign state: Article 124(2).

3. International terrorism: Article 126.

4. Genocide: Article 127.

5. Crimes against human security: Article 128.

6. Use of weapons of mass destruction: Article 134.

7. Violation of the laws or customs of war

[associated with intentional murder]: Article

135(3).

8. Aggravated murder: Article 139(2).

9. Terrorism [associated with murder or committed

by an organised group]: Article 289(3).

10. Treason [associated with murder]: Article 356(2).

11. Conspiracy or other acts committed with the

aim of seizing state power [resulting in death or

associated with murder]: Article 357(3).

12. Act of terrorism: Article 359.

13. Sabotage [committed by an organised group or

resulting in death]: Article 360(2).

14. Murder of a police ofcer: Article 362.

None of these offences provide for a mandatory

death sentence.

Since 1989 the death penalty has only been applied

for intentional aggravated murder (Article 139 of

the Criminal Code). The only exceptions are two

sentences handed down in 1995 for rape of an under-

aged girl leading to aggravated consequences (Article

115(4) of the 1960 Criminal Code), and in 2011, two

people were sentenced to death for terrorism (Article

289(3)).

In its review of Belarus in 1997, the Human Rights

Committee expressed its concern over the use of the

death penalty and recommended a “thorough review

of relevant legislation and decrees be restricted to

the most serious crimes […], and that its abolition

be considered by the State party at an early date.”

16

The Committee against Torture also renewed this

recommendation in its review of Belarus in 2011.

Prohibited categories

According to Article 59 of the Criminal Code, the

death penalty cannot be applied to:

Persons under 18 years of age at the time the

crime was committed.

Women.

Men who reached the age of 65 at the time of

sentencing.

Article 28 of the Criminal Code provides that a person

who, during the commission of a socially dangerous

act, was “insane” i.e. could not realise the actual

character and social dangerousness of his action

(inaction) due to chronic mental illness, temporary

mental disorder, dementia or a morbid state of mind

is not criminally liable. Where mental illness is proved,

the court may apply compulsory medical measures.

16 UN Human Rights Committee Concluding Observations: Belarus, 19 November 1997, CCPR/C/79/Add.86, paras. 8 and 11.

12 Penal Reform International

A person who commits a crime in the state of limited

mental illness is not exempt from criminal liability,

but the fact may be taken into account as mitigating

factor during the sentencing hearing.

17

Article 92 of the Criminal Code also provides that a

person who becomes ill (“mentally disordered”) after

sentencing shall be exempt from punishment and

may be subjected to compulsory medical measures

by the court’s decision. In case of recovery, the court

may decide to re-apply the death sentence or another

punishment.

V Legal framework: alternative

sanctions to the death penalty

in Belarus

Life imprisonment as a relatively new form of

punishment was rst introduced into the 1960

Criminal Code on 31 December 1997. Following the

adoption of the new Criminal Code in 1999, Article 58

made provision for life imprisonment as an alternative

to the death penalty for the offences associated

with intentional iniction of death under aggravating

circumstances.

Length of life imprisonment

According to Article 58(4) of the Criminal Code, a

person sentenced to life imprisonment, may have

that sentence substituted for a denite term of

imprisonment after serving a minimum of 20 years

imprisonment. The court takes into account the

prisoner’s behaviour, the state of health, and age.

Life sentence applicable crimes

The Criminal Code sets out 14 articles whereby a

life sentence may be imposed (they are the same

offences as for death penalty applicable crimes).

None of these offences provide for a mandatory life

sentence:

1. Initiation or waging of aggressive war: Article

122(2).

2. Act of terrorism against a representative of a

foreign state: Article 124(2).

3. International terrorism: Article 126.

4. Genocide: Article 127.

5. Crimes against human security: Article 128.

6. Use of weapons of mass destruction: Article 134.

7. Violation of the laws or customs of war

[associated with intentional murder]: Article

135(3).

8. Aggravated murder (Article 139 part 2);

9. Terrorism [associated with murder or committed

by an organised group]: Article 289(3).

10. Treason [associated with murder]: Article 356(2).

11. Conspiracy or other acts committed with the

aim of seizing state power [resulting in death or

associated with murder]: Article 357(3).

12. Act of terrorism: Article 359.

13. Sabotage [committed by an organised group or

resulting in death]: Article 360(2).

14. Murder of a police ofcer: Article 362.

Prohibited categories

The restrictions on the application of life

imprisonment are the same as for the death penalty:

Persons under 18 years of age at time the crime

was committed.

Women.

Men who reached the age of 65 at the time of the

passing of a sentence by a court.

Mentally-ill.

17 Article 29 of the Criminal Code.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 13

VI Application of the death

penalty/life imprisonment: fair

trial procedures

Presumption of innocence

Article 26 of the Constitution legally guarantees the

right to be presumed innocent.

However, according to independent experts, the

presumption of innocence is often undermined in

practice due to a lack of judicial independence,

ineffective legal assistance and inequality between

the prosecution and the defence. The Working Group

on arbitrary detention recommended that legislation

be aligned with international standards in order to

ensure the respect for the presumption of innocence,

for the principles of opposition and adversarial

procedure and equality of means in all phases of the

criminal procedure.

18

Trial by jury

In Belarus, trial by jury does not exist in law.

Article 32 of Criminal Procedure Code stipulates

that offences punishable by long-term (over 10

years) imprisonment or by death must be heard

by a panel of one judge and two lay judges called

People’s Assessors. According to Article 354(4) of

the same Code, the death penalty may be imposed

on the accused only if she/he is found guilty by a

unanimous decision of all three judges. This system is

not equivalent to trial by jury, and lay judges as a rule

follow the opinion of the professional judge.

On 10 October 2011, President Lukashenko signed

decree No. 454 “On measures to improve the activity

of general courts of the Republic of Belarus”, which

includes, inter alia, consideration of the possibility of

introducing jury trials to Belarus. However, no steps

have been taken yet to implement this decree in

practice.

The right to adequate legal assistance

Articles 17 and 20 of the Code of Criminal Procedure

guarantee the right to a legal defence. If a person

is accused of committing a crime of “high gravity”,

which includes those that warrant a sentence of

death or life imprisonment, the participation of

a lawyer is compulsory.

19

The Ministry of Justice

administers legal aid for indigent defendants.

Local human rights activists have raised concerns

about the quality and independence of legal

representation in criminal cases, especially legal

defence undertaken by legal aid lawyers. In 2006,

an inquiry was conducted among life-sentenced

prisoners.

20

Out of 100 lifers questioned, only 30

percent were satised with the services of their legal

aid defence. Complaints concerned the fact that

the lawyers were negligent and indifferent in relation

to their cases, or that their lawyers were frequently

replaced. Many of those interviewed noted that

lawyers do not play any signicant role in the judicial

system.

Furthermore, the rights of the defendant are often

not observed in practice. Article 60(2)(8) of the Code

for Criminal Procedure stipulates that a person who

has condentially assisted on a case cannot be

questioned as a witness without his or her consent

and the consent of the prosecuting authority. Due

to this rule, the prosecutor has the opportunity to

use sources of information that cannot be cross-

examined by the defence, thereby undermining the

equality of arms between prosecution and defence.

The UN Working Group on arbitrary detentions raised

concerns about adequate legal assistance, raising

examples of court-appointed lawyers for indigent

defendants demanding to be paid to be present

during interrogations.

21

The Working Group also

raised concerns that defence lawyers have limited

or nonexistent access to prosecutorial evidence

and expertise and thus have difculty preparing and

executing a defence.

22

18 Report of the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention: Mission to Belarus, 25 November 2004, E/CN.4/2005/6/Add.3, para. 83.

19 Article 45 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.

20 Information received from Irina Kuchvalskaya, Belarusian Association of Women-Lawyers.

21 Report of the Working Group on arbitrary detentions: Belarus, supra n. 18, para. 42.

22 Ibid, para. 79.

14 Penal Reform International

Independence of the judiciary

A lack of judicial independence in Belarus is a major

concern. The selection, promotion and dismissal of

judges are neither based on objective criteria nor

transparent. In practice, judges are appointed by the

President on the advice of the Ministry of Justice and

the Chairperson of the Supreme Court,

23

which implies

political inuence over the appointment of the judiciary.

Furthermore, the law lacks clear criteria on the tenure

of judges’ appointment (from ve years to life).

The report

24

of the Special Rapporteur on the

independence of judges and lawyers on his country

visit to Belarus in June 2000 raises concerns that

Belarusian judges are not unbiased. He expresses

concern that a large number of inexperienced judges,

poor working conditions and their dependence on

the government enhance opportunities for exerting

pressure on the judiciary and creates opportunities for

corruption. Low levels of remuneration of judges and

their dependence on the executive branch and the

Presidential administration in matters of promotion

and sustaining their conditions of service threaten the

ability of judges to make decisions free of political

inuence.

In its consideration of Belarus in 2011, the Committee

against Torture also indicated that the independence

of the judiciary was still not being fullled and

raised concerns about provisions in Belarusian

law on discipline and removal of judges, and their

appointment and tenure, which does not guarantee

their independence towards the executive branch of

government.

25

Language of the court

Article 13 of the Code on Judicial System and

Status of Judges provides that legal proceedings

are conducted in Belarusian or Russian. Those

participating in the proceedings who do not know

these languages have the right to get acquainted

with the materials of the case and to participate in

proceeding through an interpreter, and to speak in

their native language. Article 365 of the Criminal

Procedure Code provides that the verdict must also

be read out in the native language of the accused or

in another language which she/he understands. In

accordance with Article 163 of the Criminal Procedure

Code the procedural costs associated with the

provision of an interpreter are covered by the state

budget.

If the defendant does not speak Belarusian or

Russian, the participation of a defence lawyer is also

compulsory. However, judges and prosecutors have

in the past rejected motions for interpreters.

26

Open hearings

Under Article 23 of the Criminal Procedure Code,

criminal trials are open to the public in all courts. The

trial of a criminal case in a closed court session shall

be permitted only in the interest of protection of state

secrets and other secrets protected by law, as well as

in cases of crimes committed by persons under the

age of sixteen, in cases of sexual offences and other

cases in order to prevent disclosure of information

about intimate aspects of life of those involved in

the case, or when it is necessary for the safety of the

victim, witnesses or other parties to the proceedings,

as well as their family members.

Those present in an open court session have the right

to conduct a written transcription or tape-recording of

the trial. Photography and video lming are allowed

with the permission of the judge presiding at the

hearing and with the consent of the parties.

However, in January 2007, the UN Special Rapporteur

on the situation of human rights in Belarus noted that

“trials are often held behind closed doors without

adequate justication, and representatives of human

rights organisations are denied access to courts to

monitor hearings.”

27

All verdicts are announced publicly.

23 National report to the Human Rights Council: Belarus, 22 February 2010, A/HRC/WG.6/8/BLR/1, para. 22.

24 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, E/CN.4/2001/65/Add.1, 8 February 2001.

25 Concluding observations of the Committee against Torture, 7 December 2011, CAT/C/BLR/CO/4, para. 12.

26 2010 Human Rights Report: Belarus, USA Department of State Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, 8 April 2011, p. 7.

27 Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus (Adrian Severin), A/HRC/4/16, 15 January 2007, para. 14.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 15

Right to an appeal by a court of higher

jurisdiction

The defendant has the right to appeal (to the

Supreme Court) against the decision of the court of

rst instance. Cassation must be submitted within

ten days after the verdict has been announced. If the

defendant is being held in custody, cassation may

be submitted ten days after they have received the

copy of the sentence. If a cassation trial relates to the

death penalty, it is compulsory for the defendant and

his lawyer to participate in the trial.

However, some death sentences have been handed

down by the Supreme Court acting as a court of rst

instance, thereby negating any right to an appeal by a

court of higher jurisdiction.

28

Right to seek pardon or commutation of the

sentence

According to Article 59(3) of the Criminal Code, the

death penalty may be commuted to life imprisonment

by pardon. The President has the power to grant

pardon.

29

The pardon procedure is determined by Presidential

Decree No. 250 (3 December 1994) which created a

Commission on Pardon Issues under the President

of Belarus. Appeals are initially considered by the

Commission before being decided by the President.

All individuals sentenced to death are automatically

considered for pardon by the President regardless

of whether a request has been submitted by the

prisoner, or even where the Commission has given a

negative recommendation. The implementation of the

death sentence is suspended pending the pardon.

According to the Ministry of the Interior, 156 persons

sentenced to death have had their sentences

commuted to life imprisonment between 1998 and

2010.

Petitions for pardon of persons sentenced to life

imprisonment are only considered by the President

if there is a positive recommendation by the

Commission on Pardon Issues.

VII: Implementation of the death

penalty: method of execution

The death sentence is executed upon receipt of

an ofcial notication of rejection of the petition for

pardon.

The death penalty is executed non-publicly, by a

shot to the back of the head.

30

Where more than one

prisoner is to be executed, executions are carried out

separately.

Those sentenced to death generally spend between

six to eighteen months on death row before being

executed.

31

For example, Sergei Morozov, Valeri

Gorbatii and Igor Danchenko, whose sentence came

into force on 9 October 2007, were executed on 5

February 2008: spending about four months on death

row.

The execution takes place in presence of a

prosecutor, prison ofcer and a doctor. The doctor

ascertains the death of the prisoner. The prison

administration noties the court that issued the

sentence that the execution has been carried out,

and the court then informs the family of the executed

person.

The condemned prisoner is not informed of the

date of his impending execution. His family are only

informed that the execution has happened after it has

taken place. The family are not given the opportunity

for a last visit to the prisoner. The body is not

returned to the family, and the place of burial is not

disclosed.

32

28 See for example the recent case of Dzmitry Kanavalau and Uladzislau Kavalyou who were sentenced to death for the Minsk metro bombings by the Supreme

Court acting as a court of first instance in November 2011.

29 Article 59(3) of the Criminal Code.

30 Article 59(1) of the Criminal Code.

31 International Fact-Finding Mission: Conditions of Detention in the Republic of Belarus, International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the Human Rights

Centre “Viasna”, June 2008, p. 31.

32 Article 175 of the Criminal Executive Code.

16 Penal Reform International

The Human Rights Committee has raised concerns

regarding the secrecy surrounding the procedures

relating to the death penalty in Belarus.

33

In 2003, after considering the Banderenko v. Belarus

case, the Human Rights Committee considered that

the refusal by the authorities to tell the mother about

her son’s execution and the refusal to let her know

the burial place were in violation of Article 7 of the

ICCPR.

34

To date, Bandarenko’s family still does not

know where their relative is buried. The same is true

for the families of all of those executed in Belarus.

In 2011, the Committee against Torture asked Belarus

to “remedy the secrecy and arbitrariness surrounding

executions so that family members do not experience

added uncertainty and suffering.”

35

VIII Application of the death

penalty: statistics

The Republic of Belarus is notoriously secretive

about the application of the death penalty, and has

historically never published ofcial statistics on the

number of death sentences issued and executions

based on its state secrecy laws.

In a resolution on the situation of human rights in

Belarus, the UN Commission on Human Rights

urged the Government of Belarus “to provide

public information regarding the execution of those

sentenced to death”.

36

The Human Rights Committee

and the Committee against Torture have also

expressed their concern at the secrecy surrounding

the procedures relating to the death penalty at all

stages.

37

The Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial,

summary or arbitrary executions recommended that

Belarus publish annual statistics on the death penalty,

and provide the names or details of individuals who

have already been executed.

38

In 2010, the Ministry of Justice reported for the rst

time that 321 people had been sentenced to death

between 1990 and 2009. The largest number of

death sentences was handed down in the period

1990–1999. In 2011, the Ministry of Internal Affairs

published on its website, for the rst time, some

information on the number of death sentences issued

between 1998 and 2010.

39

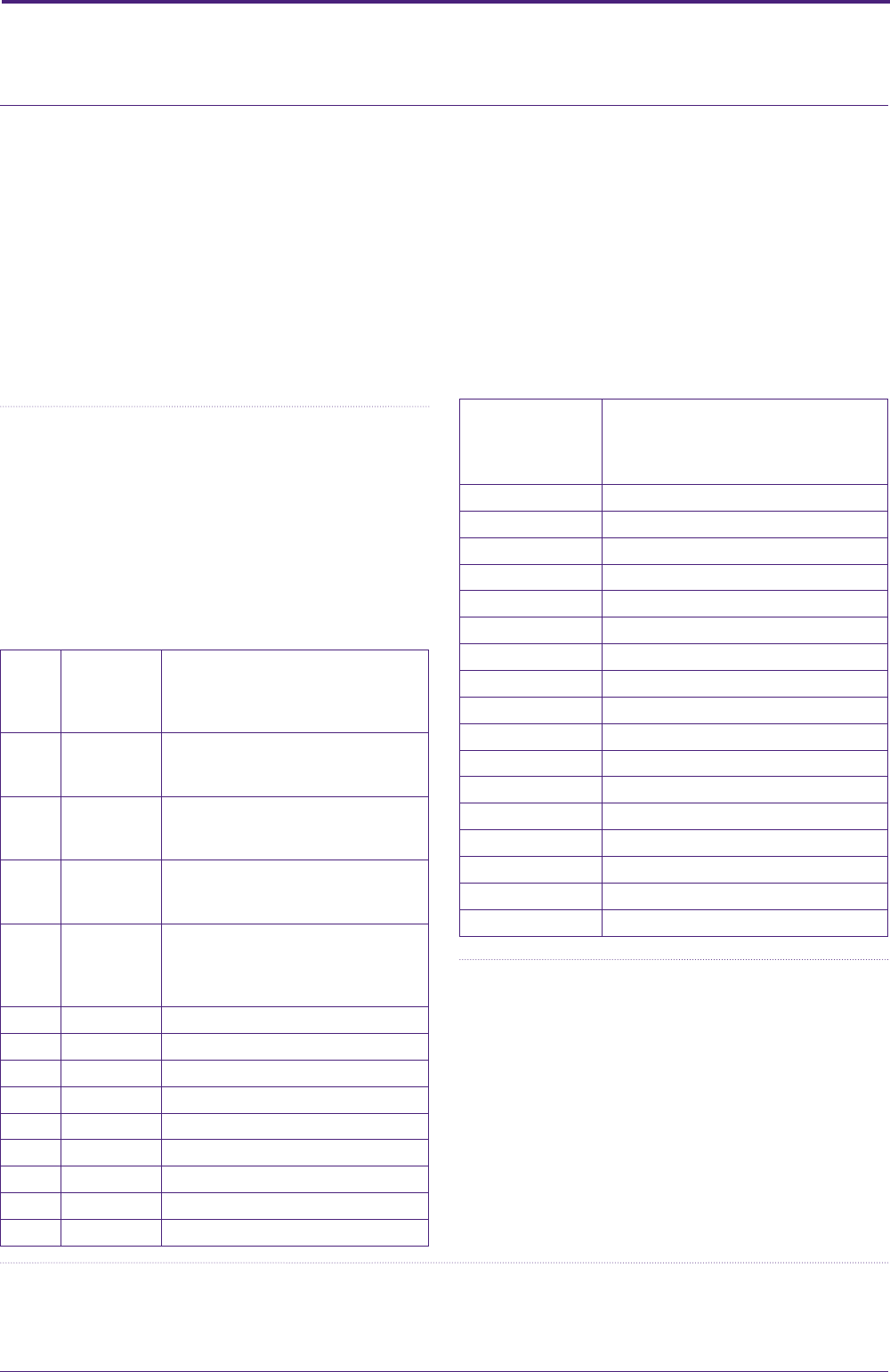

Year Number of people sentenced

to death

2011 2

2010 2

2009 2

2008 2

2007 4

2006 9

2005 2

2004 2

2003 4

2002 4

2001 7

2000 4

1999 13

1998 47

1997 46

1996 29

1995 37

Total 216

33 Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee, supra n. 16, paras. 8 and 11.

34 UN Human Rights Committee, Communication 886/1999, 3 April 2003, CCPR/C/77/D/886/1999.

35 Concluding Observations Committee against Torture, supra n. 25, para. 27.

36 Situation of human rights in Belarus, 12 April 2005, E/CN.4/2005/L.32, item 2(j); and Comments of Belarus to the concluding observations of the Committee

against Torture (CAT/C/BLR/C/4), 16 January 2012, CAT/C/BLR/CO/4/Add.1, para. 6.

37 Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee, supra n. 16, para. 8.

38 Report on the transparency and imposition of the death penalty, Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary killings (Philip Alston), 24 March 2006,

E/CN.4/2006/53/Add.3, para. 17.

39 Official website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs <http://mvd.gov.by/ru/main.aspx?guid=9091>.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 17

Statistics about the number of executions carried out

still remains a state secret. However, various sources,

including Belarusian human rights organisations, local

media and international organisations such as Amnesty

International, provide information about the number of

executions of which PRI have been able to collate.

Year Number of people executed

2012

(to date)

2

2011 2

2010 2

2009 0

2008 4

2007 At least 1

2006 Unknown

2005 At least 4

2004 Unknown

2003 Unknown

2002 5

2001 7

2000 10

1999 13

1998 47

1997 46

Total At least 143

Judicial practice shows that for several years

the death penalty has been applied primarily in

cases of premeditated murder with aggravating

circumstances.

40

2012 Executions

On 15 March 2012, Dzmitry Kanavalau and Uladzislau

Kavalyou were reportedly executed soon after

President Alexander Lukashenka refused clemency

appeals.

41

Kanavalau and Kavalyou were sentenced

to death by the Supreme Court, acting as the Court

of rst instance, for an alleged series of bomb attacks

in Belarus, including an explosion in a Minsk metro

station on 11 April 2011. According to Amnesty

International,

42

their sentence followed a awed

trial that fell short of international fair trial standards

and left no recourse for appeal, other than to the

President for clemency. There were allegations

that the two men were forced into confessing and

there was no forensic evidence linking either of

them to the Minsk explosion including no traces

of explosives were found on either of them. During

the trial Kavalyou retracted his confession. His

mother claimed that both men were beaten during

interrogation. Belarus considered the complaint for

violation of the right to life

43

submitted by Kanavalau

and Kavalyou to the UN Human Rights Committee on

15 December 2011 as invalid, arguing that national

remedies had not been exhausted.

44

2011 Executions

Some day between 11 and 19 July 2011, Andrei

Burdyka and Aleh Hryshkautsou were executed

despite their cases pending at the UN Human Rights

Committee. The Human Rights Committee had

explicitly requested, under rule 92 of its Rules of

Procedure, that Belarus take preliminary measures

to not carry out executions until the results of their

review had been submitted. Andrei Burdyka and Aleh

Hryshkautsou alleged that they had been subjected to

torture at the pre-trial investigation stage and had not

received a fair trial. Burdyko and Grishkovets had been

sentenced to death on 14 May 2010 by the Grodno

Regional Court for the murder of three people; their

sentence was upheld by the Supreme Court on 17

September 2010. A request for clemency was refused.

On 21 July 2011, the Human Rights Committee sent

a letter to the Belarus Permanent Mission in Geneva,

40 Prospects for abolition of the death penalty in the Republic of Belarus, Grigory A. Vasilevich and Elissa A. Sarkisova, The death penalty in the OSCE area:

Background Paper 2006, OSCE-Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, p. 11.

41 Statement by the International Commission against the Death Penalty on Belarus: Execution of Dmitry Konovalov and Vladislav Kovalyov, 19 March 2012,

<http://www.icomdp.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ICDP-Statement-on-Belarus-March-2012.pdf>.

42 Death Sentences and Executions 2011, Amnesty International, ACT 50/001/2012, p. 30.

43 Article 6 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

44 The Human Rights Committee shall not consider any communication of an individual who has not exhausted all available domestic remedies, unless these would

be unreasonably prolonged (Article 5(B) of the Optional Protocol to the ICCPR).

18 Penal Reform International

expressing concern over the execution of Burdyka

and Hryshkautsou, in violation of the Committee’s

request for interim measures of protection. The

Committee’s Chairperson, Ms. Zonke Zanele

Majodina, stressed on that occasion to “deplore

the fact that, by proceeding to execute these two

individuals, Belarus has committed a grave breach

of its obligations under the Optional Protocol to the

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

[…] The imposition of a death sentence after a trial

that did not meet the requirements for a fair trial

amounts to a violation of articles 14 and 6 of the

Covenant.”

45

2010 Executions

Andrei Zhuk and Vasily Yuzepchuk were believed

to have been executed in Minsk around 18 March

2010.

46

The Human Rights Committee had also

requested interim measures for Zhuk and Yuzepchuk.

According to the testimonies of Andrei Zhuk and

Vasily Yuzepchuk and as supported by medical

records, they had been repeatedly subjected to

torture. Vasilii Yuzepchuk stated that he was beaten,

starved, given unknown pills and forced to take

alcohol. As a consequence he lost the ability to

adequately evaluate what was happening to him.

There had been no proper investigation into these

allegations.

47

2008 Executions

Sergei Morozov, Valery Gorbaty and Igor Danilchenko

were reportedly executed on 5 February 2008.

48

IX Application of life

imprisonment: statistics

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs,

49

in the

period from 1998 to 2010, 144 life sentences were

issued, and 156 death sentences were commuted

to life imprisonment, meaning at least 300 men are

currently serving a life sentence in Belarus. Statistical

information for 2011 is unavailable.

Year Number of people

sentenced to life

imprisonment

The number of

people whose

death sentence was

commuted to life

imprisonment

2010 2 4

2009 5 3

2008 9 3

2007 7 4

2006 7 5

2005 8 6

2004 12 5

2003 12 5

2002 15 18

2001 11 20

2000 18 24

1999 29 27

1998 3 32

Total 144 156

In August 2010, the government Working Group on

the death penalty visited Zhodino prison where life-

sentenced prisoners are incarcerated, and found that

the number of offenders serving this sentence has

noticeably reduced in recent years.

45 Press release of the UN Human Rights Committee, 27 July 2011, <http://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews aspx?NewsID=11268&LangID=E>.

46 Belarus executes two men: Andrei Zhuk and Vasily Yuzepchuk, Amnesty International, 22 March 2010.

47 Human Rights House Network letter of concern to Alexander Lukashenko, President of the Republic of Belarus, 18 April 2010, <http://humanrightshouse.org/

Articles/13997.html>.

48 Council of Europe Secretary General Terry David condemns executions in Belarus, Council of Europe, 6 February 2008.

49 Official website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, <http://mvd.gov.by/ru/main.aspx?guid=9091>.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 19

X Implementation of the death

penalty/life imprisonment:

prison regime and conditions

Location of imprisonment for death row and

life sentenced prisoners

Death row inmates are held at the pre-trial detention

centre No. 1 in Minsk. Executions are carried out in

the same place.

Those sentenced to life imprisonment are

incarcerated in:

Pre-trial detention centre No. 8 in Zhodino

(approximately 45km from Minsk).

Colony No. 13 in Glubokoye (approximately

160km from Minsk).

Zhodino was established in 2000 and has facilities

for 100 prisoners. By 2003 the institution was

overcrowded and the administration had to place four

prisoners in cells built for two. In 2008 it was decided

to transfer lifers who have served at least ten years

without breaching the prison rules or committing

additional crimes to the colony in Glubokoye, where

the regime is less strict. The colony in Glubokoye has

subsequently also become overcrowded, meaning

that the living conditions for lifers do not reect

international standards.

Cost of imprisonment

There is no information regarding the cost of

imprisoning a prisoner on death row or of a life

sentence.

An estimation of the nancial cost is difcult to

assess due to a restriction of information and the high

levels of ination in Belarus. However, expenditures

on death row and for lifers are much higher than other

prisoners because of the high security measures

imposed.

Prison regime

According to the Criminal Executive Code of Belarus,

adult offenders serve their prison sentence in

correctional facilities, which are subdivided into four

regimes:

1. Correctional colony-settlement.

2. Penal colonies for rst-time prisoners.

3. Correctional colonies for repeat offenders.

4. Correctional colonies of special regime.

Prisoners on death row and those serving a life

sentence must serve their sentence in a correction

colony of special regime, which has higher security

requirements and stricter conditions for inmates.

Conditions and treatment of detention

There is no ofcial information regarding death row

conditions in Belarus, and researchers were unable

to visit these prison cells. However, reports indicate

that death row inmates are being held in solitary

connement, with limited access to fresh air or

exercise. The conditions of imprisonment for those

sentenced to death are set out in Article 174 of the

Criminal Executive Code. A prisoner on death row is

entitled to visits from their defence lawyer or other

persons having the right to provide legal assistance,

without limitation in number and duration; to send

and receive letters without limits; to have one short

family visit per month (up to four hours); to have visits

from a priest; to receive parcels ever three months;

and to receive necessary medical assistance.

In November 2011, the Committee against Torture

expressed concern at reports of the poor conditions

of persons sentenced to death in Belarus and that

some death row prisoners were not provided with

fundamental legal safeguards.

50

The Committee

called on Belarus to take all necessary measures to

improve the conditions of detention of persons on

death row; and to ensure they are afforded all the

protections provided by the CAT.

The conditions of imprisonment for those sentenced

to life are established in Article 173 of the Criminal

Executive Code. Lifers are housed in cells and are

50 Concluding observations Committee against Torture, supra n. 25, para. 27.

20 Penal Reform International

required to wear dark robes marked by the rst

letters of the words “life imprisonment”. Legally,

prisoners are to be incarcerated two persons per cell;

in practice in Zhodino colony there are usually four

or more prisoners per cell, while in colony No. 13 of

Glubokoye, there may be four or even six prisoners

per cell.

51

Overcrowded cells have become the norm

over the last ten years. At the request of the prisoner,

or if there is a threat to the safety of a prisoner, he

may be placed in solitary connement subject to the

decision of the prison administration.

The living conditions of lifers during the rst ten

years of their sentence are especially harsh. They

are entitled to two short visits per year (visits can be

up to two or three hours through a glass partition);

to receive two parcels per year; to walk for 30

minutes per day; and to spend a specic amount of

money from their accounts on food and essentials.

According to the Criminal Executive Code, lifers may

spend funds from their personal account on food and

essentials “in the amount of three basic amounts”.

The “basic amount” is a universal measure, which is

currently set at 35,000 Belarusian rubles or 3.4 Euros.

From 1 April 2012 it will go up to 100,000 Belarusian

rubles or 9.4 Euro).

From the time they wake up until the time they go to

bed, life sentenced prisoners can walk or sit at a table

on benches screwed to the oor. Lying on their bed

is forbidden. When a prisoner is taken out of their cell

(for a walk, for a visit, or to talk with a prison ofcial)

he is only allowed to move in a certain position – with

arms held behind his back in handcuffs, bending

down and looking at the oor.

Those who violate the prison rules can be deprived of

visits, parcels, moved to a disciplinary cell, or sent to

solitary connement for up to six months.

If a lifer has served at least ten years of their

sentence without any violations of the prison rules

or committing any further criminal offences, they

may be transferred from the special regime colony

to a correction colony which has slightly less harsh

conditions and a reduced security regime. Transfer

is decided by court on the basis of an application

submitted by the prison administration approved by a

local monitoring commission.

Following a transfer, a lifer would be entitled to

one additional visit per year; to spend additional

money from his account (in the amount of four basic

amounts); to receive an additional two more parcels

per year; and to exercise for up to one hour per day.

The sanitary conditions of the cells are very poor.

Prisoners have requested that they be allowed to

use their own tableware and clothes; that they can

remove their coats when it is hot; and to allow them

to wash their uniforms themselves. There is a lack of

time or facilities for washing clothes and bed linen

and drying facilities. Prisoners have also complained

about the improper distribution of sleeping facilities

(“legs of another convict are in front of my face”).

52

There is a lack of well-balanced and nutritional food

for prisoners. This is caused by a lack of appropriate

resources as well as various problems in the food

supply chain. Lifers are only permitted to receive two

parcels per year, which means that even if their family

had the means to supplement their diet, they could

not do so on a regular basis.

Access to medical care

According to Article 10(6) of the Criminal Executive

Code, all prisoners have the right to access health

care. From a 2006 inquiry of life sentenced prisoners,

approximately 90 percent of those interviewed

reported health problems.

53

More than half of the

respondents (52) had some form of chronic illnesses,

the majority being gastrointestinal problems. The

spread of TB has also been a serious concern for

prisoners, which is compounded by overcrowded

cells, and a lack of appropriate nutrition. The UN

Developmental Programme reported in September

2009 that none of Belarus’ prisons fully comply with

the World Health Organisation’s TB infection control

guidelines.

The majority of lifers interviewed in 2006 were not

satised with the level of psychiatric care provided.

51 How Belarusian Lifers Serve Their Sentences, Olga Antsipovich, Komsomolskaya Pravda, 4 August 2009, <www.kp.by/daily/24337/528445/>.

52 Information received from Irina Kuchvalskaya, Belarusian Association of Women-Lawyers.

53 Ibid.

The abolition of the death penalty and its alternative sanction in Eastern Europe: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine 21

Approximately 30 percent suffered from some form of

mental health issues.

A psychologist based in Zhodino colony stated that

a prisoner is subject to obligatory psychological

testing, and prisoners may speak with a psychologist

if they wish, but not all of them do.

54

There is only one

psychologist available at Zhodino.

Mr. A.A. Kralko, the head specialist of medical

services of the Department of Execution of

Punishments (PED) of the Ministry of Internal Affairs

has stated that the nancing of penitentiary facilities,

including that needed for adequate health care, is not

enough.

55

This is especially compounded by the rising

costs of resources (staff, food, medicines etc), and

the growing number of inmates.

Rehabilitation and social reintegration

programmes

Those sentenced to life imprisonment spend at least

23 hours a day in their cell. There are virtually no out-

of-cell activities, and minimal in-cell activities. There

is a lack of access to education, employment, or any

other rehabilitative programmes, and most lifers are

only entitled to a small number of family visits per

year, often under very restrictive conditions.

Article 173(2) of the Criminal Executive Code makes

provisions for lifers to undertake some form of work

programme, however there are none available in

practice. Prison ofcials explained that this was due

to the special security requirements for lifers.

Article 10 of the Criminal Executive Code establishes

that all prisoners should have access to exercise and

sports. However, lifers are only entitled to 30 minutes

of walking per day and up to one hour if transferred

from the special regime colony. A prison ofcer, in

response to why sports and exercise are severely

limited for lifers, stated that the “prison personnel do

not want serious criminals to have good muscles,

[and] the metal parts of training equipment may be

used improperly, and there is a high risk of traumas….

We’ll have to write a lot of explanations if a convict

gets hurt from sporting equipment and not from us”.

56

Almost all prisoners have demonstrated some interest

in accessing books, newspapers and magazines. A

high proportion of inmates have expressed a desire

to access educational literature including legal texts.

Life sentenced prisoners have also made requests

for educational programmes, particularly secondary

education and to study foreign languages, information

technology, and psychology; to train in some kind

of profession (carpenter, builder, tailor, electrician,

accountant etc); to take part in creative activities; and

to have access to sports equipment.

The possibility to perform religious rites and access

priests is permitted in Zhodino and Glubokoye, and

there are some rooms provided for prayers.

Conditions for parole

Article 90 of the Criminal Code stipulates that

parole (or conditional release) can be applied only

if the prisoner’s behaviour is very good and shows

rehabilitation.