DISCONNECTED, DISADVANTAGED, AND

DISENFRANCHISED:

EXPLORATIONS IN THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

Mark N. Cooper

OCTOBER 11, 2000

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dhavan V. Shah of the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin-

Madison oversaw the conduct of the survey research and provided analysis of that data for this report.

Major support for the conduct of the survey research was provided by the Digital Media Forum, a media

policy consortium established by the Ford Foundation. Additional support was provided by research

funding to Dhavan Shah from the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of

Wisconsin-Madison, was well as grants to William Eveland (Assistant Professor, School of Journalism and

Communication, The Ohio State University) from the Institute for Social, Behavioral, and Economic

Research (Social Science Research Grants Program) and the Department of Communication, University of

California at Santa Barbara. The author wishes to thank DDB-Chicago for access to some of the data

presented in this report.

Consumers Union is a nonprofit membership organization chartered in 1936 under the laws of the State

of New York to provide consumers with information, education and counsel about goods, services, health,

and personal finance; and to initiate and cooperate with individual and group efforts to maintain and

enhance the quality of life for consumers. Consumers Union's income is solely derived from the sale of

Consumer Reports, its other publications and from noncommercial contributions, grants and fees. In

addition to reports on Consumers Union's own product testing, Consumer Reports, with approximately

4.5 million paid circulation, regularly carries articles on health, product safety, marketplace economics

and legislative, judicial and regulatory actions which affect consumer welfare. Consumers Union's

publications carry no advertising and receive no commercial support.

The Consumer Federation of America is the nation's largest consumer advocacy group, composed of over

two hundred and forty state and local affiliates representing consumer, senior, citizen, low-income, labor,

farm, public power and cooperative organizations, with more than fifty million individual members.

The interpretation of the data are solely the responsibility of the author.

BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY

Dhavan V. Shah, Ph.D

Assistant Professor

School of Journalism and Mass Communication

University of Madison-Wisconsin

Voice: 608.262.0388 Fax: 608.262.1361

Internet: dshah@facstaff.wisc.edu

The mass diffusion of digital media and the explosive growth of the Internet are reshaping the lives and

lifestyles of many Americans. Over the last decade, the rise of digital technologies has fundamentally

altered how people work, play, communicate, socialize, and otherwise engage their communities. Major

transformations in the American media landscape have accompanied these changes. In response to these

trends, the Digital Media Forum, a media policy consortium funded by the Ford Foundation, funded a

large scale study of American’s Internet attitudes and behaviors, and their policy preferences concerning

digital media. To ensure this research was objective and systematic, the study was designed and

conducted independently by Professor Dhavan Shah, Ph.D., of the School of Journalism and Mass

Communication, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The resulting study relies on national survey data collected in February 1999 and June 2000 from a single

panel of respondents to address a variety of issues that these changes in electronic media have

introduced. Topics examined by the broader study include: the extent of the digital divide in America,

support for programs to increase public access to the Internet, opinion concerning electronic privacy and

the restriction of media content, preferences about “broadband” and digital television, levels of support

for non-commercial uses of the Internet, the connection between the Internet and civic life, and concerns

about media mergers and Internet open access. The last of these topics is the focus of this report.

The February 1999

data were collected as part of an annual mail survey — the “Life Style Study” —

conducted by Marketfacts on behalf of DDB-Chicago, an international marketing communications

company. Via mail, a massive number of people were asked to express their willingness to participate in

mail or telephone surveys, and if so, to provide basic demographic information. A balanced sample was

then drawn from among the 500,000+ people agreeing to become part of the pre-recruited “mail panel.”

In order to ensure representativeness, the starting sample of approximately 5,000 mail panelists was

adjusted within the subcategories of race, gender, and marital status to compensate for expected

differences in return rates. The sample was also drawn to reflect demographic distributions within the 9

Census divisions of household income, population density, panel member’s age, and household size.

Applying this stratified quota sampling method, of the roughly 5,000 Life Style surveys distributed to mail

panelists, 3,388 usable responses were received, for a response rate of 67.8 percent. This rate of

response is considerably higher than the typical national survey.

For the June 2000

wave of the study, we engaged Marketfacts to recontact the individuals who

completed the February 1999 survey. Due to some erosion, 2,737 questionnaires were mailed out to

1999 Life Style Study respondents. To ensure a high response rate — and a more representative sample

— a substantial incentive was offered for completing the survey. The response rate for this survey was

70.1%, with 1,902 respondents completing the questionnaire. The data presented in this report focuses

on the respondents who completed both waves of the study. The margin of error for the results is about

±3.0% when using the full sample. For a validation of these Life Style data against other national survey

data, see Putnam (2000, Appendix 1).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I

I. INTRODUCTION 1

A. GROWING CONCERN ABOUT THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

B. OUTLINE AND PURPOSE OF THE PAPER

II. DEFINING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE 3

A. CONNECTEDNESS IN CONCEPT

B. TECHNOLOGY OWNERSHIP AND USE

III. DEMOGRAPHIC CORRELATES AND CAUSES OF CONNECTEDNESS 5

A. CURRENT CONNECTION

B. INTENTION TO GET CONNECTED

IV. CONSEQUENCES OF BEING DISCONNECTED 15

A. PARTICIPATING IN CYBERSPACE

B. CYBERSPACE MAY BE INCREASE INEQUALITY OF

OPPORTUNITY

V. CONCLUSION 21

LIST OF TABLES

1. DIGITAL DIVIDE DEFINED BY INTERNET CONNECTION 4

2. CURRENT AND FUTURE CONNECTEDNESS 10

3. CONSEQUENCES OF BEING DISCONNECTED: 16

ACTIVITIES IN PHYSICAL SPACE AND CYBERSPACE

4. ATTITUDES TOWARD TECHNOLOGY 18

LIST OF FIGURES

1. INCOME, RACE AND CONNECTEDNESS 7

2. INCOME, AGE AND CONNECTEDNESS 8

3. INCOME, CHILDREN AND CONNECTEDNESS 9

4. DIFFUSION OF COMPUTER OWNERSHIP AND INTERNET USE 12

5. DIFFUSION OF COMPUTER OWNERSHIP: 13

HOUSEHOLDS ABOVE/BELOW MEDIAN INCOME

6. DIFFUSION OF INTERNET USE: 14

HOUSEHOLDS ABOVE/BELOW MEDIAN INCOME

7. CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF FUTURE INTERNET ADOPTION 20

COMBINING DEMOGRAPHIC AND ATTITUDINAL FACTORS

i

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

From the first moment that the Internet showed potential as a commercial medium and

as a platform for public communications, policymakers have been debating the question of

whether differential access to the Internet poses a public policy problem. The public policy

debate over the digital divide stems from concerns that the denial of access to the emerging

digital society diminishes the economic chances or restricts the ability to participate in civic and

political life of those who are excluded from online activity. Furthermore, it is a concern that

certain demographic groups are systematically excluded from participation.

This paper uses the results of a large and detailed national survey to explore the nature

and impact of the digital divide.

♦ With a precise empirical definition, it documents the existence of the digital divide and

demonstrates that it is not likely to disappear any time soon.

♦ A direct comparison of a broad range of cyberspace and physical space activities for

commerce, information gathering, education, civic discourse and political participation,

shows that the disconnected are, in fact, disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE EXISTS AND PERSISTS

The

Fully Connected

constitute 36% of the population with an Internet Service

Provider or high speed Internet access at home.

The

Partially Connected

constitute 17% with basic Internet or e-mail service at home.

The

Potentially Connected

constitute 21% who have no Internet service, but do own

a computer at home or have a cellular phone.

The

Disconnected

constitute 26% who do not have any Internet service and do not

have a computer or a cell phone.

There are sharp differences in demographics across the groups, which can be

highlighted by contrasting the disconnected to the fully connected (see Table ES-1). Lower

income, elderly and minorities are more likely to be among the disconnected.

TABLE ES-1: DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

DISCONNECTED FULLY CONNECTED

MEAN INCOME ($000) 25.5 45.2

AT LEAST COLLEGE GRAD (%) 13 46

BLACK (%) 12 7

AGE (Years) 53 44

MANAGERIAL OCCUPATION (%) 8 33

Patterns of connection to the Internet in the recent past (see Figure ES-1) and

intentions to get connected in the near future support the conclusion that, while digital

technologies are spreading through the population, the divide persists for some groups and is

not likely to disappear in the near future. The diffusion of Internet use indicates that those in

ii

iii

the bottom half of the income distribution are lagging behind by a half decade and that a

substantial part of the population will remain disconnected. Forty percent of the respondents

say they do not have the Internet at home today and they do not intend to get connected in

the next four years.

THE DISCONNECTED ARE DISADVANTAGED AND DISENFRANCHISED

The digital divide is an important policy issue because the Internet has already become

a significant means of communications and commerce in society. Households with access use it

for important personal, cultural and civic activities while those without access are at a

disadvantage in conducting similar daily activities. They cannot shop as effectively or

conveniently, are not offered attractive pricing plans, cannot gather information or contact

public officials and other people as effectively. They become less effective consumers and

citizens relative to their fellow consumers who have access.

Table ES-2 shows that there are very substantial differences between groups in their use

of the Internet. If using the Internet is helpful for conducting the economic and political

activities identified in Table ES-2, it is quite clear that the disconnected are at a disadvantage

and are being disenfranchised.

At the same time that the data document the dramatic difference between participation

in physical space and cyber space, they also show that the difference in participation in

cyberspace is not a mere reflection of a lower level of participation among these groups in real

space. The disconnected and potentially connected households do participate a little less in

physical space, but not nearly as much less as they do in cyberspace. With the shift of activity

to the Internet that has already occurred and the prospect of even more dramatic shifts in the

future, the threat that the disconnected are disadvantaged and disenfranchised grows.

♦ The problem is not that the disconnected do not participate in physical space, it is

that they cannot participate in cyberspace. People who are able to participate in

physical space are becoming disadvantaged and disenfranchised in cyberspace.

The respondents recognize this as a potential problem. Almost two-thirds of respondents

express the concern that technological progress can have the effect of increasing the gap

between rich and poor (see Table ES-3). Those not intending to get connected express the

greatest concern about this gap (68 percent agree), but even those currently connected express

concern (60 percent). Being left behind by the “information revolution” is also a concern

expressed by 57 percent of the respondents. Most interestingly, the group which expresses the

greatest concern about this gap (71 percent) is the group that intends to get connected in the

near future.

TECHNOLOGY ATTITUDES AND THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

The existence and persistence of the gap is not for lack of appreciation among those

who are disconnected that they are missing out on something important (see Table ES-3).

Respondents have a very strong appreciation for the importance of technology in general and

computers in particular. Those who intend to get connected express exactly the same level of

appreciation as the currently connected. This pattern holds for both computers and the

Internet.

iv

TABLE ES-2

CONSEQUENCES OF BEING DISCONNECTED

ACTIVITIES IN PHYSICAL SPACE AND CYBERSPACE

(Percent of Respondents Reporting Activity; Cyberspace in Bold)

Disconnected Potentially Partially Fully

BASIC SKILLS

Ever used the Internet 49 65 95 97

Don’t have a clue what the Internet is about 58 42 14 12

Use Internet at work 11 27 43 47

Use Internet in public 7 15 18 15

PERSONAL PRODUCTIVITY

Searched for a Job online 14 13 23 28

Searched for business info online 21 30 46 52

COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY

Made an online purchase 11 19 53 57

Visited website seen in an Ad 14 25 64 62

Visited website seen in a Program 17 28 65 67

INFORMATION GATHERING

Read a newspaper 92 94 97 97

Obtained news or sport results online 25 30 60 65

Read a news magazine 62 67 72 79

Visit a news website 18 25 62 70

Attended a lecture 29 44 55 55

Obtained educational information online 26 42 72 73

INTERACTING WITH GOVERNMENT

Contacted a local public official 31 35 40 40

Visited website of a gov't agency 13 17 36 40

CIVIC DISCOURSE

Wrote a letter to the editor 20 18 24 27

E-mailed a Newspaper 8 6 15 16

Discussed politics with a neighbor 46 47 56 50

Discussed politics in an e-mail 7 4 9 12

POLITICAL EXPRESSION

Circulated a petition for a politician 10 11 12 12

Signed or forwarded a petition online 5 5 9 14

Attended a political rally 22 23 18 19

Visited a politician’s website 8 7 18 19

v

TABLE ES-3

ATTITUDES TOWARD TECHNOLOGY

INTERNET STATUS

NOW IN 4 YEARS NOT 4 YEARS

TECHNOLOGY AND THE DIVIDE

Technology advances increase the gap between rich and poor 60 63 68

I worry that some people will be left behind by the 55 71 63

“information revolution”

TECHNOLOGY IMPORTANCE

If you want to be successful nowadays, you need 91 91 83

to understand technology

Children learn more when they have access to technology 87 87 84

COMPUTERS

We’d be better off without computers (disagree) 87 87 68

Computer skills are vital for tomorrow 96 96 93

INTERNET/ACCESS

I feel the Internet can help enhance my career 83 82 51

I feel the Internet can help enhance my education 59 62 32

TECHNOLOGY SKILLS

I consider myself computer-savvy 57 30 21

I Don’t’ have a clue what the Internet is about and 87 70 56

what it can do for me (disagree)

The Internet is too expensive 52 65 66

vi

The disconnected appear somewhat different in their attitudes toward technology. They

express slightly less appreciation for the importance of technology and computers, but a great

deal less belief that the Internet can do them good. While about half of those on the Internet

say it is too expensive, about two-thirds of those not on the net feel this way.

There are much larger differences across the groups in terms of knowledge and

command of the technology. The disconnected do not have the resources and they lack the

skills. They fully appreciate technology and computers, but less so the Internet. Their limited

experience may account for the latter difference.

In fact, the computer appears to play a key role in getting on line. Four fifths of those

who have computers are on the Internet. Among those who do not have a computer,

respondents who say they will get connected within the next four years, also say,

overwhelmingly (86 percent), they will get a computer

in that same time period. Among those

who do not have a computer and who say they will not get connected in the next four years,

the overwhelming majority (81 percent) also say they will not get a computer

in that time

period. In essence getting people PC hardware and training is the key.

CONCLUSION

As an empirical investigation into the nature of the digital divide, this study does not

offer a specific set of policy recommendations. The objective is to establish an appreciation of

the nature and impact of the digital divide.

♦ While computer ownership and Internet use continue to grow, the "digital divide" that

separates those Americans connected to the Internet from those who are not persists

and is not likely to disappear any time soon.

♦ The gap puts millions of Americans at a serious disadvantage in our increasingly “online”

society.

♦ The more important online activity becomes, the more problematic the digital divide will

be if it persists.

♦ Those at risk are in vulnerable groups – lower income, elderly and minorities.

Understanding that these vulnerable groups are harmed by their lack of access to

technology becomes the starting point for seeking cost-effective avenues to address this

deprivation. The steps to be taken to overcome the digital divide emerge from the attitudes

toward and experience with information-age technologies.

♦ The digital divide is not the result of a failure of those without access to appreciate the

importance of technology, rather it results from a maldistribution of skills and

opportunities.

♦ Public policy to close the digital divide must give people the human capital skills to use

information age technologies, the experience to make them comfortable with these

technologies and the resources to obtain the necessary hardware at home, where they

conduct their daily activities.

1

I. INTRODUCTION

A. GROWING CONCERN ABOUT THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

From the first moment that the Internet showed potential as a commercial medium

and as a platform for communications, policymakers have been debating the question of

whether differential access to the Internet poses a public policy problem. Reactions to a

Washington Post

article summarizing the findings of a mid-1999 report on the digital divide

suggest how prominent the debate has become. In a front page story, the newspaper

summarized a report from the National Telecommunications Information Administration as

follows:

Despite plummeting computer prices and billions of dollars spent wiring public

schools and libraries, high-income Americans continue to predominate in the online

world.

The findings were immediately cast in highly charged public policy terms by

President Clinton:

There is a growing digital divide between those who have access to the digital

economy and the Internet and those who don’t, and that divide exists along the

lines of education, income, region, and race… If we want to unlock the potential of

our workers, we have to close that gap.

By contrast, a spokesman for the ultraconservative Cato institute – Executive Vice

President David Boaz – dismissed the notion of the digital divide:

We’ve got a new technology spreading more rapidly than any new technology has

spread in history. And of course, it doesn’t spread absolutely evenly. Richer people

have always adopted new technology first – and that’s not news. There’s no such

thing as information haves and have-nots, there are have-nows and have-laters.

The families that don’t have computers now are going to have them in a few years.

Half a decade earlier, Manuel Castells, Professor of Sociology and Planning at the

University of California, Berkeley and author of a three volume work on

The Rise of the

Network Society

, anticipated this rancorous debate. He noted that timing in the distribution

and adoption of technology is a critical factor in determining economic chances, especially in

a digital age.

There are large areas of the world, and considerable segments of the population,

switched off from the new technological system . . . Furthermore, speed of

technological diffusion is selective, both socially and functionally. Differential timing

in access to the power of technology for people, countries, and regions is a critical

source of inequality in our society (p. 34).

In the digital age, waiting “a few years” for technology to trickle down may seriously

impede the economic aspirations of the “have laters.” “Having later” may be almost as bad

2

as “having not” because the good opportunities are gone and the patterns of activity are set,

leaving latecomers excluded and switched off.

The important point about the digital divide is not simply that some people have the

technology and others do not, but that not having it puts people at a disadvantage and cuts

them off from participation in important economic, social, cultural and political activities.

B. OUTLINE AND PURPOSE OF THE PAPER

This paper uses the results of a large and detailed national survey to explore the

nature and impact of the digital divide.

Section II presents a new, empirical definition of the digital divide. It documents the

existence of the divide.

Section III presents an examination of the demographic correlates and causes of the

digital divide. While it is clear that digital technologies are spreading through the population,

it is also clear that for some groups the divide persists and is not likely to disappear in the

near future.

Section IV examines the consequences of the divide. By presenting a direct

comparison of a broad range of commercial, informational, educational, civic and political

activities of individuals in physical space to those in cyberspace, it shows that the

disconnected are, in fact, disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

The intensity of the digital divide debate stems from the intersection of several

factors. It is clear that the Internet and activities in cyberspace are transforming society

powerfully and rapidly. Because the Internet has been an open and accessible place for new

forms of expression, it was hoped (believed) that it would democratize society and equalize

opportunity. The maldistribution of access to cyberspace flies in the face of that hope. In

fact, because the opportunity to participate is less equally distributed in cyberspace than in

physical space, the persistence of this problem may make matters worse. It is a new source

of inequality in society.

At the start of the 20

th

century, an industrial age was underway. Economic growth

was matched with a broad (but imperfect) expansion of economic opportunity and political

participation. At the start of the 21

st

century, as the Internet age begins, we are faced with

a similar challenge. Because things move so fast in cyberspace, the need to respond to the

challenge is urgent.

The purpose of this study is not to assign fault for the digital divide, rather it is to

understand its nature, persistence and consequences. Appreciation of the impact of the

divide should convince policymakers that action is necessary to close it. An understanding of

the causes of the divide should help choose the policies that will accomplish the goal of

eliminating the divide effectively and quickly.

3

II. DEFINING THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

A. CONNECTEDNESS IN CONCEPT

About eighteen months ago, the Consumer Federation of America and Consumers

Union published a report entitled

The Digital Divide Confronts the Telecommunications Act of

1996: Economic Reality vs. Public Policy

.

1

In that analysis households were divided into four

categories primarily on the basis of their telecommunications usage – whether or not they

had more than one phone line and a cell phone – as well as Internet usage.

Since that report was issued, the debate over the digital divide has been heated, with

intensive scrutiny of a number of technology characteristics of population groups being

considered. As the debate has shifted more toward the growth of e-commerce and the role

of high-speed networks, attention has been focused on computer ownership, Internet

usage, and the convergence of communications and video entertainment into interactive TV.

We believe it is now more relevant to focus on connectedness to computer networks

in defining the digital divide. These categories correspond closely to our past categories of

telecommunications usage, but provide greater focus on newer services. Accordingly, we

developed a scale of actual and potential connection to the Internet using four categories:

Fully Connected

- Respondents who report that they have a commercial

Internet Service Provider or high speed Internet access at home.

Partially Connected

- Those who have basic internet service or basic e-mail

service at home.

Potentially Connected

- Those who have no Internet service, but do own a

computer at home or have a cellular phone.

Disconnected

- Those who do not have any Internet service and do not

have a computer or a cell phone.

We use cellular connectedness to supplement the assessment of potential Internet

connectedness for two reasons. First, as the Internet moves increasingly to wireless

Internet platforms, these people will have a device for connection to the Internet. Second, a

cellular user's ability to pay the cost of a cell phone indicates a certain amount of

discretionary income that the consumer is willing to spend on communications services.

B. TECHNOLOGY OWNERSHIP AND USE

Table 1 provides a description of the characteristics of these groups across four

dimensions – demographics and each of the major technologies that are converging in the

Internet Century. It also provides a comparison to our earlier discussion of the digital divide.

1

February 1999.

4

TABLE 1

DIGITAL DIVIDE DEFINED BY INTERNET CONNECTION

(IN PERCENT, UNLESS OTHERWISE NOTED)

Dis- Potentially Partially Fully

Connected Connected Connected Connected

DIGITAL DIVIDE DEFINED

BY INTERNET/COMPUTER

(2000)

DEMOGRAPHICS

POPULATION 26 21 17 36

MEAN INCOME (x1000) $25.5 $34.3 $39.6 $45.2

AT LEAST COLLEGE GRAD 13 26 44 46

BLACK 12 11 4 7

AGE (in Years) 53 47 45 44

MANAGERIAL 8 22 26 33

HOUSEHOLD SIZE 2.1 2.5 2.7 2.8

COMPUTER/INTERNET

COMPUTER 0 59 95 96

INTERNET COMMERCIAL 0 0 0 100

INTERNET BASIC 0 0 100 69

MODEMS 0 30 75 84

COMMUNICATIONS

CELL PHONES 0 72 58 69

FAX 2 16 22 33

LONG DISTANCE 71 85 88 89

VIDEO ENTERTAINMENT

CABLE TV 56 64 63 78

DIGITAL CABLE 4 7 4 15

SATELITE 8 15 23 20

MVPD HOUSEHOLDS 62 73 78 87

DIGITAL DIVIDE DEFINED

BY COMMUNICATIONS

(1999)

DEMOGRAPHICS

POPULATION 45 16 15 24

MEAN INCOME (X1000) $22.5 $41.2 $35.8 $53.8

COMPUTER/INTERNET

INTERNET 0 0 62 87

COMMUNICATIONS

CELL PHONES 0 100 10 91

FAX 5 10 28 50

VIDEO ENTERTAINMENT

MVPD HOUSEHOLDS 63 76 74 86

5

Just over one-quarter (26 percent) of the respondents are disconnected, having no

Internet service at home, no computer and no cellular phone. Just over one-fifth (21

percent) are potentially connected (having either a computer or a cell phone, but no

Internet). Just over one-sixth (17 percent) of the respondents are partially connected. Over

one-third (36 percent) of households are fully connected.

The categories of connectedness correlate with a number of technology and other

household characteristics. There is a steady rise of possession/consumption of each of the

categories of technologies as one moves from the disconnected to the fully connected.

Among the fully and partially connected, computers are ubiquitous, with 96 percent

reporting a computer at home. Modems are also widespread in these two groups, with over

three quarters possessing this communications device. Fifty-nine percent of the potentially

connected have a computer and half of these have a modem.

Embedded in these numbers is the fact that 81 percent of those who have a

computer are either fully or partially connected. In other words, once respondents have a

computer, they are very likely to be connected.

Twenty-nine percent of the disconnected respondents report they do not have a long

distance telephone service (they may use dial-around) and 38 percent do not have a

multichannel video service (cable or satellite). Among the fully connected, 11 percent say

they do not have a long distance service (they may use a dial-around service or their cell

phones). Thirteen percent say they do not have a multichannel video service.

Although different characteristics were used to create the definition of the digital

divide in this paper (here, Internet-based v. rates of telecommunications usage in the earlier

paper), there are strong similarities with the characteristics of the groups identified in the

earlier study. The ‘have-nots’ in each analysis have much lower levels of consumption of

each of the technologies.

III. DEMOGRAPHIC CORRELATES AND CAUSES OF CONNECTEDNESS

The fact that there are differences between groups in their ownership and use of

technology is not a major public policy concern in itself. Rather, the public policy debate

over the digital divide stems from concerns that failure to participate in the emerging digital

society constitutes a deprivation, imposes a hardship or diminishes the economic chances of

those who are not participating. Furthermore, it is a concern that certain demographic

groups are excluded from participation.

A. CURRENT CONNECTION

There are sharp differences in demographics across the groups on all dimensions.

Table 1 lists several demographic characteristics that have an independent and significant

effect on connectedness, as discussed below.

6

Income is lowest in the disconnected group ($25,500), highest in the fully connected

group ($45,200). Those who are fully and partially connected are much more likely to have

at least a college degree and be employed in managerial or professional occupations. The

fully and partially connected are less likely to be black. Disconnected households are older

and tend to be smaller.

The six demographic characteristics discussed above have statistically significant

effects in a multiple regression analysis.

2

They explain about one-quarter of the variance in

connectedness. Other demographics that were tested but did not have statistically

significant effects once these variables are taken into account include gender, employment

status, urban/rural location, residence tenure, and Hispanic origin.

Figures 1, 2 and 3 give a taste of the multivariate analysis for three demographic

variables that are frequently invoked in public policy debates over the digital divide – race,

age and the presence of children in the home. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between

income, race and connectedness. Income is clearly the more important factor, but race is

also significant. For the lowest income group and several of the highest, blacks are clearly

more likely to be disconnected.

Figure 2 depicts the relationship between income, age and connectedness. Older

respondents are much more likely to report being disconnected. For those 65 and over, the

gap is quite large, particularly for middle income respondents, who report a gap of 20+

percentage points. Even for the middle-aged group (45-64) compared to the youngest

group (18-44) there is a significant gap at all income levels.

Figure 3 shows that households with children are significantly more likely to have a

computer, beyond the lowest income group. The differences are large (20 percentage

points or more) for most income groups.

2

The key results of the regression analysis are as follows.

CAUSES OF CONNECTIVITY

DEPENDENT VARIABLE = CONNECTEDNESS SCALE

BETA SIGNIFICANCE

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

INCOME .288 .0000

AGE -.189 .0000

EDUCATION .153 .0000

RACE -.063 .0074

HOUSEHOLD SIZE .049 .0317

MANAGER .048 .0383

Multiple R = .48, R Square = .23

7

8

9

10

B. INTENTION TO GET CONNECTED

As noted in the introduction, some argue that the gap between those who are

connected and those who are not is closing rapidly and there is no need for public policy to

intervene. These survey data do not support that optimism. Approximately 47 percent of

the respondents are not connected today. Just one in eight of those respondents expects to

be connected within four years (see Table 2). In other words, forty percent of the

respondents do not expect to be connected four years from now. In cyberspace that is a

long time.

TABLE 2

CURRENT AND FUTURE CONNECTEDNESS

(PERCENT OF TOTAL POPULATION)

NOT NOW WILL GET WILL NOT GET

CONNECTED CONNECTED CONNECTED

WITHIN 4 YEARS WITHIN 4 YEARS

POTENTIALLY 21 5 16

CONNECTED

DISCONNECTED 26 2 24

TOTAL 47 11 40

The potentially connected group is much more likely to say they intend to get

connected. Just under a quarter of that group intends to get connected. In contrast, among

the disconnected only one in thirteen expresses this intention. In the potentially connected

group there is no significant difference between those who have a computer (23 percent)

and those who have a cell phone (25 percent) in their intention to get connected.

While people's perceptions of their futures are not necessarily equivalent to their

actual futures— they could get wired much more quickly than they expect— we believe that

perceptions are critical. If people do not believe that getting online is realistic for them, they

are less likely to pursue these kinds of opportunities.

Applying the same demographic model to future intentions to get connected as was

applied above to current connectedness reveals a rather different outcome. While income,

age and education remain significant factors, the other demographic factors are not

significant. The magnitude of the effects are smaller as well. Overall, these demographic

factors explain one-twelfth of the variance in intention to get connected. The impact of

11

income is cut in half and that of education reduced by about one-third. The impact of age

remains about the same.

3

Listening to what people say they intend to do is one indicator of what may happen

in the years ahead. Looking at what people have done in the recent past is another indicator

of what may happen. Figures 4, 5, and 6 show the diffusion curves for computers and

Internet use for the total population and for the households above and below the median of

household income. These are based on responses to questions that asked “when did you

first get a computer” and “when did you first use the Internet.” The charts reflect the date

of first adoption for those who still have the technology. We choose income as the control

variable in the analysis because it is far and away the most important causal factor in

technology adoption.

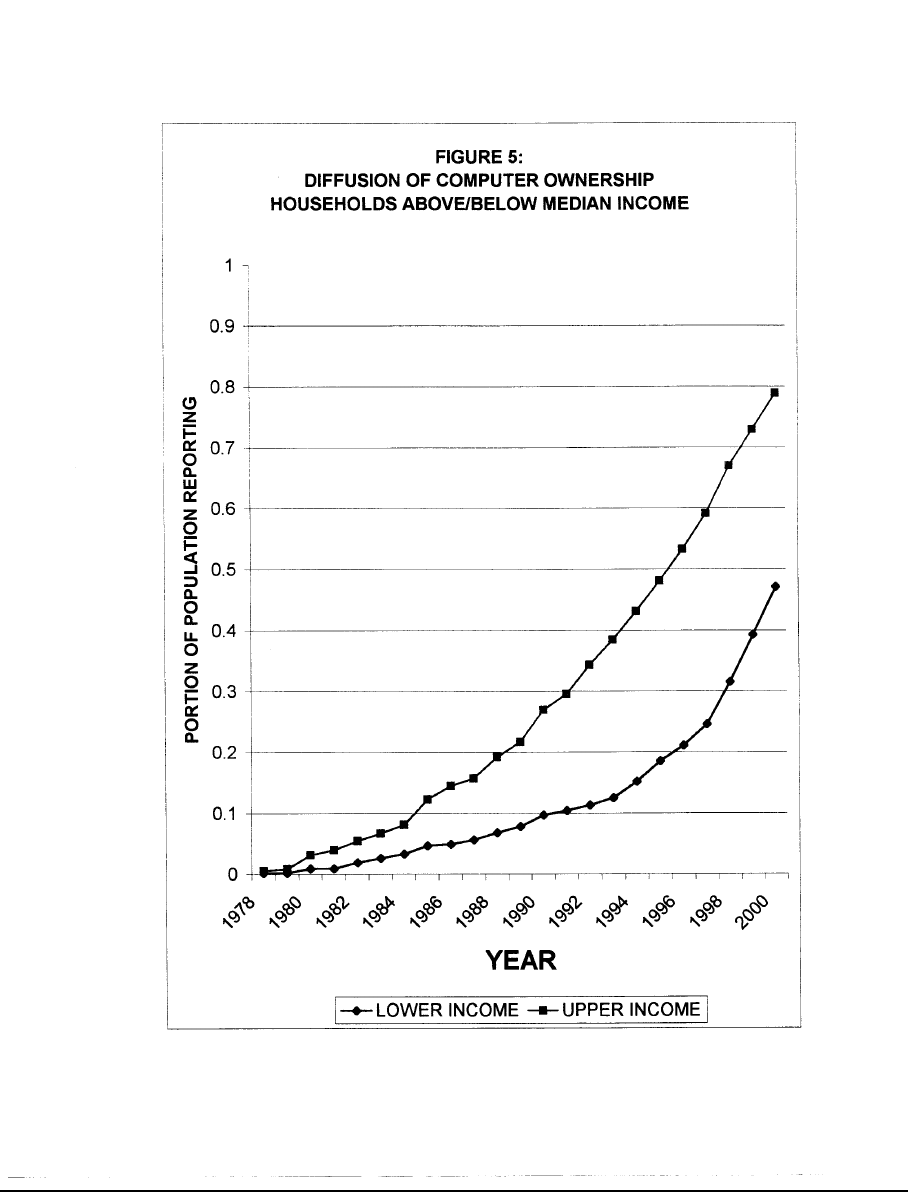

Figure 4 shows rapid diffusion at the overall societal level. Figures 5 and 6 show that

there is a substantial digital divide. Looking at the figures, one could argue that there is a

five-year divide. That is, those with incomes below the median achieve adoption rates about

five years after those with incomes above the median.

Figures 5 and 6 provide the empirical basis for the perception that the divide is

growing. Measured in absolute terms, the gap has grown to 40 percentage points. The

Figures also provide the basis for claiming that the gap will begin to close. Adoption among

households with above median income will begin to top out. Adoption among households

with incomes below the median will continue and start to close the gap, if

the bottom half

continues to behave as the top half did.

If the diffusion curve for below median income households follows that of households

above median, we would expect a 50-60 percent penetration rate in the lower income

groups in four years. At that point, this group might contribute about 20-25 percent of the

total population to the not-connected group. The above median households will likely not

get to 100 percent.

4

This group might contribute another 5 to 10 percent of the total

population to the not-connected group. This suggests the disconnecteds would still

constitute 25 to 35 percent of the population. Thus, the respondents may be a little

3

The key results of the regression analysis are as follows.

CAUSES OF INTENTION TO BECOME CONNECTED

DEPENDENT VARIABLE = PLAN TO GET INTERNET IN THE NEXT 4 YEARS

BETA SIGNIFICANCE

INDEPENDENT VARIABLES

INCOME .15 .0000

AGE -.199 .0000

EDUCATION .103 .0032

Multiple R = .30, R Square = .09

4

For example, only 90 percent of the households with incomes above the median have a long distance company,

while 77 percent of the below median income households do.

12

13

14

15

pessimistic in what they say about their intentions to connect, but they are not too far off

from the historical pattern. There will still be a substantial gap well out into the future for

lower income households.

The big ifs

in the analysis are – when do the curves start to top out? Will the below median

group sustain the same rate of diffusion as the above median income group? The answers to

these questions will hinge on factors like income growth, the cost of hardware to get

connected and the price of being connected.

IV. CONSEQUENCES OF BEING DISCONNECTED

What does it matter if a household is disconnected from the network? The Internet

has already become an important means of communications and commerce in society and

households that do not have access have more difficulty conducting their daily activities.

They cannot shop as effectively or conveniently, are not offered attractive pricing plans,

cannot gather information or contact public officials and other people as effectively. They

become less effective consumers and citizens relative to their fellow citizens who have

access.

The deprivation is not only relative, it may be absolute. They may be cut off from

important personal, cultural and civic activities. Businesses may effectuate market

segmentation by restricting their activities to cyberspace, since this screens out less

attractive customers. For example, instead of 800 numbers, advertisers may give web sites

for further information; jobs may be listed on websites, but not advertised in physical space.

As the Internet becomes the dominant means of communication and commerce in the 21

st

century, the cost of being cut off would rise in relative and absolute terms.

To examine this issue we looked at activities in which respondents engage in

cyberspace and compared them to activities in physical space. Given the general orientation

of the debate over the digital divide, we have focused on what might be called economic and

political activities, rather than social activities. For example, economic activities include

basic skills for using the Internet, personal productivity improvement and commercial

activity. Political activities include civic discourse and political expression. Information

gathering and interacting with government could be considered to fall in both categories.

A. PARTICIPATING IN CYBERSPACE

Table 3 shows that there are very substantial differences between groups in their use

of the Internet. It is interesting to note that half of the disconnected and two-thirds of the

potentially connected report that they have used the Internet at some time. This is in

contrast to virtually all of those who are partially or fully connected. Although the

disconnecteds have used the Internet, they are more likely to say they do not understand

what it is about.

16

TABLE 3

CONSEQUENCES OF BEING DISCONNECTED

ACTIVITIES IN PHYSICAL SPACE AND CYBERSPACE

(Percent of Respondents; Cyberspace in Bold)

Disconnected Potentially Partially Fully

BASIC SKILLS

Ever used the Internet 49 65 95 97

Don’t have a clue what the Internet is about 58 42 14 12

Use Internet at work 11 27 43 47

Use Internet in public 7 15 18 15

PERSONAL PRODUCTIVITY

Searched for a Job online 14 13 23 28

Searched for business info online 21 30 46 52

COMMERCIAL ACTIVITY

Made an online purchase 11 19 53 57

Visited website seen in an Ad 14 25 64 62

Visited website seen in a Program 17 28 65 67

INFORMATION GATHERING

Read a newspaper 92 94 97 97

Obtained news or sport results online 25 30 60 65

Read a news magazine 62 67 72 79

Visit a news website 18 25 62 70

Attended a lecture 29 44 55 55

Obtained educational information online 26 42 72 73

INTERACTING WITH GOVERNMENT

Contacted a local public official 31 35 40 40

Visited website of a gov't agency 13 17 36 40\

CIVIC DISCOURSE

Wrote a letter to the editor 20 18 24 27

E-mailed a Newspaper 8 6 15 16

Discussed politics with a neighbor 46 47 56 50

Discussed politics in an e-mail 7 4 9 12

POLITICAL EXPRESSION

Circulated a petition for a politician 10 11 12 12

Signed or forwarded a petition 5 5 9 14

Attended a political rally 22 23 18 19

Visited a politician’s website 8 7 18 19

17

If using the Internet is helpful for conducting the economic and political activities

identified in Table 3, it quite clear that the disconnected are at a disadvantage and are being

disenfranchised. The ability of the disconnected to improve their lot, conduct commercial

activity, gather information, interact with government, engage in civic discourse and political

expression is restricted relative to online members of their community. This is over one-

quarter of the population. The potentially connected also suffer the disadvantage and

disenfranchisement, albeit at a slightly lower level than the disconnected. This is more than

one fifth of the population.

B. CYBERSPACE MAY BE INCREASING INEQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY

Finding that households that are disconnected are much less likely to make use of the

Internet for a variety of activities considered important for personal improvement, economic

advancement and civic/political participation does not necessarily demonstrate a digital

divide. After all, these households are less educated and have lower incomes. This

difference in participation in cyberspace might simply be a reflection of their lower levels of

participation in real space. This would still be a public policy concern, but it would not be a

uniquely digital divide issue.

On the other hand, if cyberspace activity is much less evenly spread across the

population than physical space activity, then it is a uniquely cyberspace problem and it could

be very significant as the role of online activity expands in the “Internet Century.” People

who are not disadvantaged or disenfranchised in physical space are becoming so in

cyberspace. As society shifts more of its important activities into cyberspace, the inequality

between people grows. The deprivation may be relative and absolute. People can still do

their physical space activities, but they are at a disadvantage compared to those who can

get things done more easily. Eventually, they could be cut off as certain activities come to

exist only in cyberspace.

In fact, there is a dramatic difference between participation in physical space and

cyber space. The disconnected and potentially connected households generally participate a

little less in physical space,

5

but not nearly as much less as they do in cyberspace. The data

are consistent with the disadvantage/disenfranchisement argument. The problem is not that

the disconnected do not participate in physical space, it is that they cannot participate in

cyberspace.

The existence and persistence of the gap is not for lack of appreciation among those

who are disconnected that they are missing out on something important (see Table 4).

Respondents have a very strong appreciation for the importance of technology in general

and computers in particular. Those who intend to get connected express exactly the same

level of appreciation as the currently connected. This pattern holds for both computers and

the Internet.

5

The one clear exception is the percentage of disconnected who report attending a lecture.

18

TABLE 4

ATTITUDES TOWARD TECHNOLOGY

CURRENTLY WILL GET WILL NOT BE

CONNECTED CONNECTED CONNECTED

TECHNOLOGY IMPORTANCE

If you want to be successful nowadays, 91 91 83

you need to understand technology

Children learn more when they 87 87 84

have access to technology

TECHNOLOGY AND THE DIVIDE

Technology advances increase the gap 60 63 68

between rich and poor

I worry that some people will be left 55 71 63

behind by the “information revolution”

COMPUTERS

We’d be better off without computers 87 87 68

(disagree)

Computer skills are vital for tomorrow 96 96 93

INTERNET/ACCESS

I feel the Internet can help 83 82 51

enhance my career

I feel the Internet can help 59 62 32

enhance my education

I would like to receive Internet 37 64 33

service through my television

TECHNOLOGY SKILLS

I consider myself computer-savvy 57 30 21

Don’t’ have a clue what the Internet is 87 70 56

and what it can do for me

(disagree)

The Internet is too expensive 52 65 66

19

The disconnected appear somewhat different in their attitudes toward technology.

They express slightly less appreciation for the importance of technology in general and

computers, but a great deal less belief that the Internet can do them good. While about

half of those on the Internet say it is too expensive, about two-thirds of those not on the

Internet feel this way.

There is also a strong sense that technological progress can have the effect of

increasing the gap between rich and poor, with almost two-thirds of respondents expressing

this sentiment. Those not intending to get connected express the greatest concern (68

percent agree), but even those currently connected express concern (60 percent). Being

left behind by the “information revolution” is also a concern expressed by 57 percent of

respondents. Interestingly, while 55 percent of the currently connected express this concern

and 63 percent of those not intending to get connected do, 71 percent of those who intend

to be connected express this concern.

This suggests that the intention to get connected may be spurred by the urgent

desire not to be left behind. Consistent with this interpretation is the fact that they are much

more likely to state that they would like to have the Internet over their TV (64 percent). In

contrast, only 37 percent of the currently connected and only 34 percent of those not intend

to get connected say they want the Internet over their TV.

There are much larger differences across the groups in terms of knowledge and

command of the technology. The disconnected do not have the resources and they lack the

skills. They fully appreciate technology and computers, but they are less likely to see the

value of the Internet to them. Their limited experience may account for the latter difference.

The very large differences of opinion between those who intend to get connected and

those who do not on the prospects for educational or career enhancement are striking. This

may reflect the fact that these technologies do not play a large or apparent role in the

current occupation/situation of the disconnected. Those who intended to get connected are

twice as likely to be in managerial or administrative occupations (24 percent to 12 percent)

and much more likely to have graduated from college (33 percent to 19 percent).

The computer appears to play a key role in getting on line. Among those who do not

have a computer, respondents who say they will get connected within the next four years,

also say, overwhelmingly (86 percent), they will get a computer

in that same time period.

Among those who do not have a computer and who say they will not get connected in the

next four years, the overwhelming majority (81 percent) also say they will not get a

computer in that time period. This is perfectly consistent with the earlier observation that 81

percent of those who have a computer are connected.

In essence, getting people PC hardware and training is the key, since once they have

one, they get online, as suggested earlier. This may be driven by the perception and current

reality that the computer is an extremely important device for personal skills. While other

means of connection to the Internet may evolve, the computer is likely to continue to be an

important tool for activities other than getting connected. For the immediately relevant time

frame of public policy analysis, it appears to be the lever for connectedness.

20

Combining the earlier discussion of demographic factors with this analysis of

attitudinal factors, we can construct a “conceptual model” of future Internet adoption (see

Figure 7). The relationships included have been discussed in the earlier analysis in and are

also statistically significant in a multivariate analysis.

FIGURE 7

CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF FUTURE INTERNET ADOPTION COMBINING

DEMOGRAPHIC AND ATTITUDINAL FACTORS

EDUCATIONAL

ENHANCEMENT

EXPERIENCE

EDUCATIONAL SAVVY

ATTAINMENT

RACE

AGE COMPUTER INTERNET

CHILDREN

INCOME

OCCUPATIONAL

ATTAINMENT

OCCUPATIONAL

ENHANCMENT

Intention to get a computer is far and away the most important factor affecting

intention to get on line. Income affects both the intention to obtain a computer and the

intention to get on line. It is by far the largest effect on both. It provides the resources.

Educational attainment and prospects for educational enhancement also affect both.

Computer savvy affects the intention to get a computer, as does occupational attainment.

Prospects for occupational enhancement affect intention to get connected. Race, age and

children affect the intention to get a computer.

21

V. CONCLUSION

As an empirical investigation into the nature of the digital divide, this study does not

offer a specific set of policy recommendations. The objective is to establish an appreciation

of the nature and impact of the digital divide.

It is clear that, while computer ownership and Internet use continue to grow, the

"digital divide" that separates those Americans connected to the Internet from those who are

not persists and is not likely to disappear any time soon. This gap puts millions of Americans

at a serious disadvantage in our increasingly “online” society. Those at risk are in vulnerable

groups – lower income, elderly and minorities.

Understanding that these vulnerable groups are harmed by their lack of access to

technology becomes the starting point for seeking cost-effective avenues to address this

deprivation. The disconnected are disadvantaged and disenfranchised.

The steps to be taken to overcome the digital divide emerge from the attitudes

toward and experience with information-age technologies. The digital divide is not the result

of a failure of those without access to appreciate the importance of technology, rather it

results from a maldistribution of skills and opportunities. Public policy to close the digital

divide should build human capital by giving people the capital skills to use information age

technologies, the experience to make them comfortable with these technologies and the

resources to obtain the necessary hardware at home, where they conduct their daily

activities.