Comparing the SEI’s

Views and Beyond Approach

for Documenting Software

Architectures with

ANSI-IEEE 1471-2000

Paul Clements

July 2005

Software Architecture Technology Initiative

Unlimited distribution subject to the copyright.

Technical Note

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

This work is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense.

The Software Engineering Institute is a federally funded research and development center sponsored by the U.S.

Department of Defense.

Copyright 2005 Carnegie Mellon University.

NO WARRANTY

THIS CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY AND SOFTWARE ENGINEERING INSTITUTE MATERIAL IS

FURNISHED ON AN "AS-IS" BASIS. CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY MAKES NO WARRANTIES OF ANY

KIND, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, AS TO ANY MATTER INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO,

WARRANTY OF FITNESS FOR PURPOSE OR MERCHANTABILITY, EXCLUSIVITY, OR RESULTS OBTAINED

FROM USE OF THE MATERIAL. CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY DOES NOT MAKE ANY WARRANTY OF

ANY KIND WITH RESPECT TO FREEDOM FROM PATENT, TRADEMARK, OR COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT.

Use of any trademarks in this report is not intended in any way to infringe on the rights of the trademark holder.

Internal use. Permission to reproduce this document and to prepare derivative works from this document for internal use is

granted, provided the copyright and “No Warranty” statements are included with all reproductions and derivative works.

External use. Requests for permission to reproduce this document or prepare derivative works of this document for external

and commercial use should be addressed to the SEI Licensing Agent.

This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number F19628-00-C-0003 with Carnegie

Mellon University for the operation of the Software Engineering Institute, a federally funded research and development

center. The Government of the United States has a royalty-free government-purpose license to use, duplicate, or disclose the

work, in whole or in part and in any manner, and to have or permit others to do so, for government purposes pursuant to the

copyright license under the clause at 252.227-7013.

For information about purchasing paper copies of SEI reports, please visit the publications portion of our Web site

(http://www.sei.cmu.edu/publications/pubweb.html).

Contents

Acknowledgments ..............................................................................................vii

Abstract.................................................................................................................ix

1 Introduction....................................................................................................1

2 The Views and Beyond Approach to Software Architecture

Documentation...............................................................................................3

2.1 A Multi-View Approach............................................................................3

2.2 Different Kinds of Views..........................................................................3

2.3 Styles ......................................................................................................4

2.4 Choosing the Views................................................................................4

2.5 A Template for Views and Information Beyond Views.............................5

3 1471 (IEEE Recommended Practice for Architectural Description of

Software-Intensive Systems)........................................................................9

4 Comparison..................................................................................................12

4.1 Comparing Definitions ..........................................................................12

4.2 Satisfying the Requirements of 1471 with V&B ....................................12

4.3 Discussion ............................................................................................13

References...........................................................................................................15

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 i

ii CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

List of Figures

Figure 1: The Template for a View........................................................................... 6

Figure 2: The Template for Documentation Beyond Views...................................... 8

Figure 3: Excerpt from Conceptual Framework of 1471........................................ 10

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 iii

iv CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

vi CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Judith Stafford, Robert Nord, James Ivers, Reed Little, and Linda

Northrop for their helpful reviews.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 vii

viii CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

Abstract

Architecture documentation has emerged as an important architecture-related practice. In

2002, researchers at the Carnegie Mellon

®

Software Engineering Institute completed

Documenting Software Architectures: Views and Beyond (V&B), an approach that holds that

documenting a software architecture is a matter of choosing a set of relevant views of the

architecture, documenting each of those views, and then documenting information that

applies to more than one view or to the set of views as a whole. Details of the approach

include a method for choosing the most relevant views, standard templates for documenting

views and the information beyond them, and definitions of the templates’ content. At about

the same time, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) was developing a

recommended best practice for describing architectures for software-intensive systems—

ANSI/IEEE Std. 1471-2000. Like V&B, that standard takes a multi-view approach to the task

of architecture documentation, and it establishes a conceptual framework for architectural

description and defines the content of an architectural description.

This technical note summarizes the two approaches and shows how a software architecture

document prepared using the V&B approach can be made compliant with Std. 1471-2000.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 ix

x CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

1 Introduction

A software architecture for a program or computing system consists of the structure or

structures of that system, which comprise elements, the externally visible properties of those

elements, and the relationships among them [Bass 03]. The quality attributes of a software

system, such as performance, modifiability, and security, are bound up in its software

architecture. A system with the wrong architecture will be a failure.

A software architecture also determines the blueprint for the project developing the software.

Teams are formed around architectural elements, which are the units of implementation, unit

testing, integration, configuration management, documentation, and a host of other activities.

Unlike code, architecture is a design artifact largely intended for use and analysis by humans.

Hence, representing it in a readable, accessible fashion for its stakeholders becomes an issue

of importance. Architecture gives the marching orders to implementers, telling them what

pieces to build and how those pieces should behave and interact with each other. It also

determines the project structure for managers, who use it to plan, schedule, and budget. It

gives the first glimpse of the system to maintainers who must change the architecture and

new team members who must become familiar with it.

Therefore, architecture documentation has emerged as an important architecture-related

practice. In 2002, researchers at the Carnegie Mellon

®

Software Engineering Institute (SEI)

completed Documenting Software Architectures: Views and Beyond [Clements 03], which

puts forth a documentation philosophy as well as a detailed approach. The philosophy is

embodied in the title: “views and beyond.” The V&B approach, as it is known, holds that

documenting a software architecture is a matter of choosing a set of relevant views of the

architecture, documenting each of those views, and then documenting information that

applies to more than one view or to the set of views as a whole. The last step ties the views

together and makes them become a holistic and integrated representation of the architecture,

as opposed to disjoint snapshots taken from different angles. The detailed approach includes

a method to choose the most relevant views, standard templates for documenting a view and

documenting the information beyond views, and definitions of the templates’ content.

While the V&B approach was being solidified, a new recommended best practice was being

formed by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). The IEEE

Architecture Planning Group (APG) was formed in August 1995 and chartered by the IEEE

Software Engineering Standards Committee (SESC) to set a direction for incorporating

®

Carnegie Mellon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office by Carnegie Mellon

University.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 1

architectural thinking into IEEE standards. The result of the APG’s deliberations was to

recommend an IEEE activity with these goals:

• to define useful terms, principles, and guidelines for the consistent application of

architectural precepts to systems throughout their life cycle

• to elaborate architectural precepts and their anticipated benefits for software products,

systems, and aggregated systems (“systems of systems”)

• to provide a framework for the collection and consideration of architectural attributes and

related information for use in IEEE standards

• to provide a useful roadmap for the incorporation of architectural precepts in the

generation, revision, and application of IEEE standards

In April 1996, the SESC created the Architecture Working Group (AWG) to implement those

recommendations, which have since been adopted by the American National Standards

Institute [ANSI] as well as IEEE and which eventually became ANSI/IEEE Std. 1471-2000

[IEEE 00]. That standard, henceforth referred to as 1471, is a recommended practice that

addresses the activities of the creation, analysis, and sustainment of architectures of software-

intensive systems and the recording of such architectures in terms of architectural

descriptions. The standard establishes a conceptual framework for architectural description

and defines the content of an architectural description.

Interest in 1471 is growing and will likely continue to grow. Although it is impossible to tell

how many projects invoke it, it is mandated for use in the Future Combat Systems (FCS)

project, a U.S. Army command-and-control system that is expected to comprise over 30

million lines of code and (therefore) whose software architecture is of supreme importance.

How does the V&B approach to architecture documentation relate to the 1471 approach to

architecture description? This technical note summarizes the two approaches and shows how

a software architecture document prepared using the former can be made compliant with the

latter.

Section 2 summarizes the V&B approach. Section 3 gives an overview of 1471. Section 4

compares the two and shows how preparing an architecture document using the V&B

approach can result in a product that is 1471 compliant.

2 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

2 The Views and Beyond Approach to Software

Architecture Documentation

2.1 A Multi-View Approach

Modern software architecture practice embraces the concept of architectural views. A view is

a representation of a set of system elements and the relations associated with them. Views are

representations of the many system structures present simultaneously in software systems.

Modern systems are too complex to be grasped all at once. Instead, we restrict our attention

at any one moment to one (or a small number) of the software system’s structures, which we

represent as views.

Some authors prescribe a fixed set of views with which to engineer and communicate an

architecture; for example, the Rational Unified Process (RUP), which is based on Kruchten’s

4+1 view approach to software [Kruchten 95] and the Siemens Four Views model

[

Hofmeister 00]. A recent trend, however, is to recognize that architects should produce

whatever views are useful for the system at hand, and the V&B approach adopts that policy.

This trend leads to the fundamental philosophy of the V&B approach stated earlier:

Documenting an architecture is a matter of documenting the relevant views and then adding

documentation that applies to more than one view.

2.2 Different Kinds of Views

There is an almost unlimited supply of views to choose from. To lend some order to an

otherwise chaotic collection of possible views, it’s helpful to think about views in groups,

according to the kind of information they convey:

1. Module views describe how the system is to be structured as a set of code units.

2. Component-and-connector (C&C) views describe how the system is to be structured as a

set of interacting runtime elements.

3. Allocation views describe how the system relates to non-software structures in its

environment.

A particular view of a system may fall squarely into one of these categories or combine

information from more than one category.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 3

2.3 Styles

A view is a representation of a structure that is present in a software system. One might show

the hierarchical decomposition of the system’s functionality into modules or how the system

is arranged into layers; another might show how the system accomplishes work through

communicating processes or the interaction of clients and servers. Still another might show

how software elements are deployed onto hardware processing and communication nodes.

An architect chooses the structures to work with and designs them to achieve particular

quality attributes using architectural styles.

1

A style is a specialization of element types (e.g.,

“client,” “layer”) and relationship types (e.g., “is part of,” “request-reply connection,” “is

allowed to use”), along with any restrictions (e.g., “clients interact with servers but not each

other” or “all the software comprises layers arranged in a stack such that each layer can only

use software in the next lower layer”).

Styles are documented in a style guide that defines each style by defining the element types

and relationship types indigenous to the style, along with any semantic restrictions on their

use. It lists what design problems the style is and is not good at addressing. The guide also

discusses any notations or analytical approaches available to the architect using that style and

refers to any related styles.

2.4 Choosing the Views

The V&B approach to choosing the views to document is a simple three-step procedure based

on the structures that are inherently present in the software and on the stakeholders and the

concerns they have that would motivate documenting the corresponding view. The steps are

described below.

Step 1: Produce a Candidate View List

Begin by building a stakeholder/view table for your project. Enumerate the stakeholders for

your project’s software architecture documentation down the rows. Be as comprehensive as

you can. For the columns, enumerate the views that apply to your system. Some views (e.g.,

decomposition, uses, and work assignment) apply to every system, while others (e.g., pipe-

and-filter, layered) only apply to systems designed according to the corresponding styles.

Once you have the rows and columns defined, fill in each cell to describe how much

information the stakeholder requires from the view: none, overview only, or detailed. We

1

A style is similar to an architectural design pattern—that is, a design pattern whose scope is

architectural. Patterns represent known, recurring design solutions. They are prepackaged sets of

design decisions, each with its own vocabulary and each having known effects on software quality

attributes. Patterns are published in the literature; perhaps the best-known catalog of architectural

patterns is the two-volume set Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture [Buschmann 96, Schmidt

00]. Architectural patterns restrict their attention to particular element and relation types, and

impose topological and behavioral restrictions on how the elements are arranged.

4 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

encourage architects to hold a workshop with stakeholders or their representatives to begin a

dialogue about what information they will need from the documentation.

The candidate view list consists of those views in which some stakeholder has a vested

interest.

Step 2: Combine Views

The candidate view list from Step 1 is likely to yield an impractical number of views. Step 2

winnows the list to a manageable size.

First, look for views in the table that require only overview depth or that serve very few

stakeholders. See if the stakeholders could be equally well served by another view that has a

stronger constituency.

Next, look for views that are good candidates to become combined views. A combined view

shows information native to two or more separate views. A rule of thumb is that if there is a

strong correspondence between the elements in two views, they are good candidates to be

combined.

Step 3: Prioritize

After Step 2, you should have the minimum set of views needed to serve your stakeholder

community. At this point, you need to decide what to do first. For example, some

stakeholders’ interests supersede others. The project manager of a company you are

partnering with often demands attention and information early and often, and you may want

to cater to his/her needs first.

2.5 A Template for Views and Information Beyond Views

No matter the view, the documentation for it is placed into a standard organization or

template comprising seven parts:

1. A primary presentation shows the elements and relationships among them that populate

the portion of the view shown in this view packet. The primary presentation should

contain the information you wish to convey about the system (in the vocabulary of that

view) first. The primary presentation is usually graphical. If so, it must be accompanied

by a key that explains or points to an explanation of the notation.

2. An element catalog details the elements (and their properties, including interfaces)

depicted in the primary presentation. In addition, if elements or relations relevant to this

view packet were omitted from the primary presentation, the catalog is where they are

introduced and explained.

3. A context diagram shows how the system (or portion of the system) depicted in the

primary presentation relates to its environment.

4. A variability guide shows how to exercise any variation points that are part of the

architecture shown in this view packet.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 5

5. An architecture background or rationale explains why the design reflected in the view

packet came to be.

6. An “other information” section contains items that vary according to the standard

practices of each organization or the needs of the particular project.

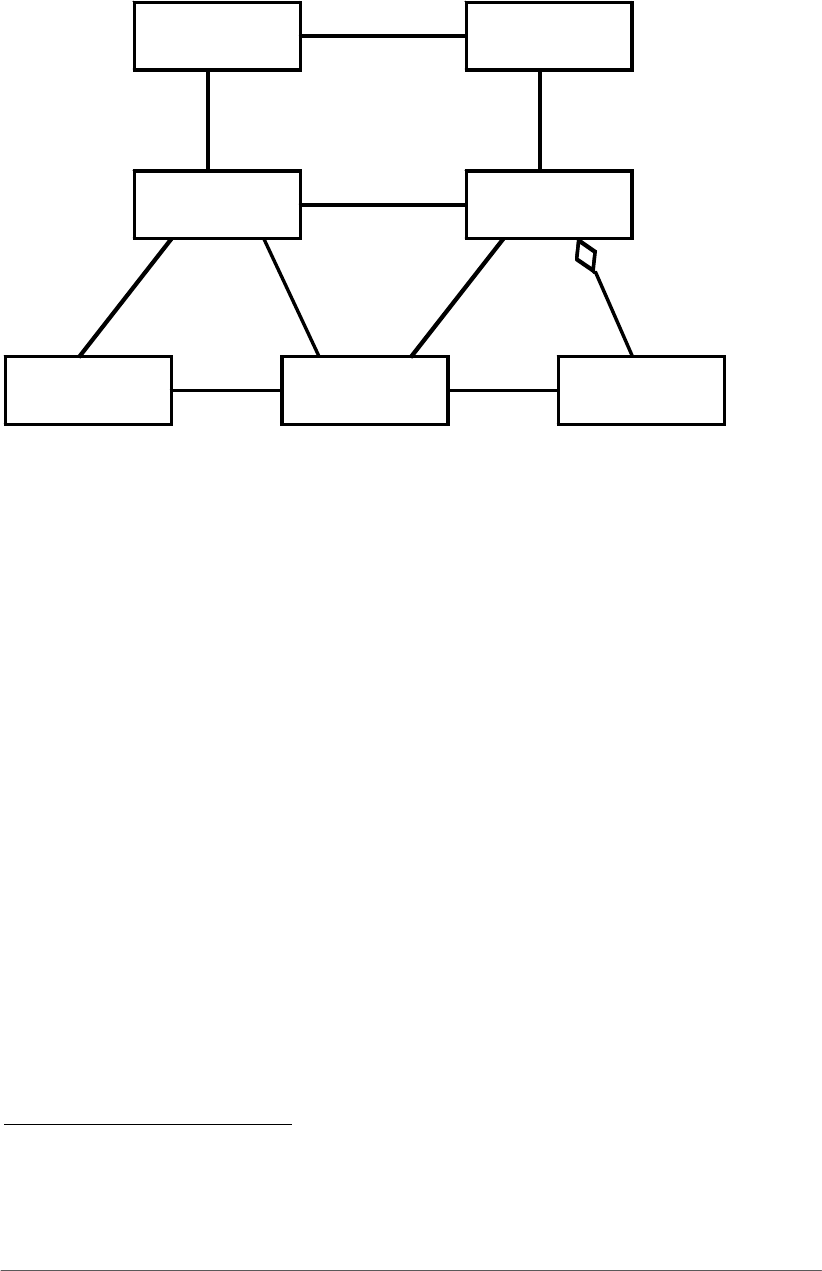

Figure 1 illustrates the template for a view.

Figure 1: The Template for a View

The final piece of architecture documentation is the information that applies to more than one

view and to the entire package. It ties together the views and provides a holistic picture of the

total design. Cross-view or “beyond views” documentation consists of the following sections:

1. Documentation roadmap. The documentation roadmap is the reader’s introduction to

the information that the architect has chosen to include in the suite of documentation. A

roadmap begins with a brief description of each part of the documentation package. For

6 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

each view in the package, the roadmap gives a description of the view’s element types,

relation types, and property types. The roadmap also gives a description of the view’s

purpose. The information can be presented by listing the stakeholders who are likely to

find the view of interest and by listing a series of questions that can be answered by

examining the view. The roadmap follows with a section describing how various

stakeholders might access the package to help address their concerns. This section might

include short scenarios such as “a maintainer wishes to know the units of software that

are likely to be changed by a proposed modification.”

2. View template. A view template is the standard organization for a view. Its purpose is to

help a reader navigate quickly to a section of interest. It helps a writer organize the

information and establish criteria for knowing how much work is left to do.

3. System overview. A system overview is a short prose description of what the system’s

function is, who its users are, and any important background or constraints. The purpose

is to provide readers with a consistent mental model of the system and its purpose.

4. Mapping between views. This shows the correspondence between individual elements

in different views. Helping a reader or other consumer of the documentation understand

the relationship between views will help that reader gain a powerful insight into how the

architecture works as a unified conceptual whole.

5. Directory. The directory is simply an index of all the elements, relations, and properties

that appear in any of the views, along with a pointer to where each one is defined and

used.

6. Project glossary and acronym list. The glossary and acronym list define terms unique

to the system that have special meaning. These lists, if they exist as part of the overall

system or project documentation, might be given as pointers in the architecture package.

7. Cross-view rationale. This section documents the reasoning behind decisions that apply

to more than one view. Prime candidates for cross-view rationale include documentation

of background or organizational constraints that led to decisions of system-wide import.

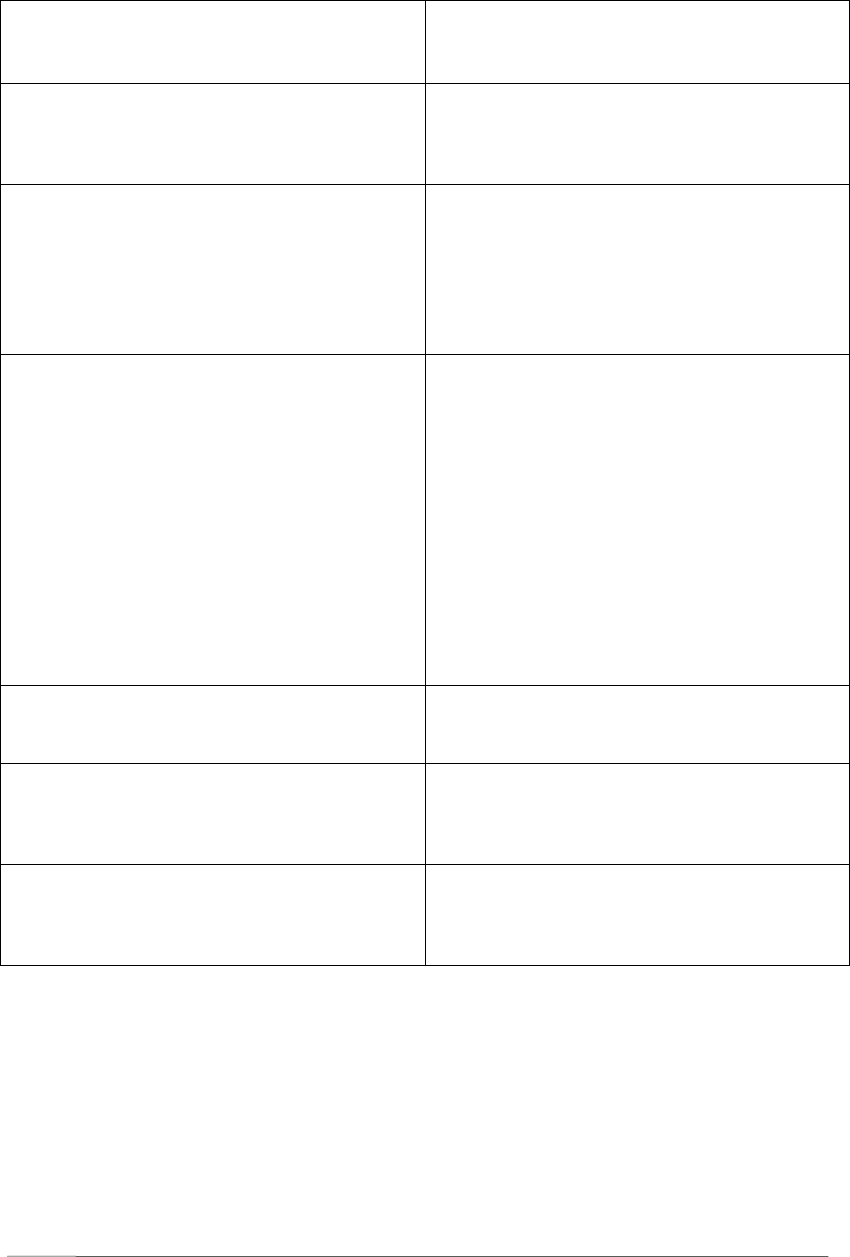

Figure 2 illustrates the seven pieces of cross-view or “beyond view” documentation.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 7

Template for Documentation Beyond Views

How the documentation is organized

Section 1. Documentation roadmap

Section 2. View template

What the architecture is:

Section 3. System overview

Section 4. Mapping between views

Section 5. Directory

Section 6. Glossary and acronym list

Why the architecture is the way it is:

Section 7. Background, design constraints, and rationale

Figure 2: The Template for Documentation Beyond Views

8 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

3 1471 (IEEE Recommended Practice for Architectural

Description of Software-Intensive Systems)

1471 draws on experience from industry, academia, and other standards bodies. The

recommendations of 1471 center on two key ideas: (1) a conceptual framework for

architectural description and (2) a statement of what information must be found in any 1471-

compliant architectural description. The conceptual framework described in the standard ties

together such concepts as system, architectural description, and view.

Figure 3 summarizes a portion of this framework in UML. In 1471, views have a central role

in documenting software architecture. In the standard, each view is “a representation of a

whole system from the perspective of a related set of concerns.” The architectural description

of a system includes one or more views. In this framework, a view conforms to a viewpoint.

A viewpoint is “a pattern or template from which to develop individual views by establishing

the purposes and audience for a view and the techniques for its creation and analysis” [IEEE

00]. In 1471, the emphasis is on what drives the perspective of a view or a viewpoint.

Viewpoints are defined with specific stakeholder concerns in mind, and the definition of a

viewpoint includes a description of any associated analysis techniques.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 9

Figure 3: Excerpt from Conceptual Framework of 1471

2

In addition to the conceptual framework, 1471 includes a statement of what information must

be in any compliant architectural description. These “shalls” include the following:

1. identification and overview information. This information includes the date of issue

and status, identification of the issuing organization, a revision history, a summary and

scope statement, the context of the system, a glossary, and a set of references.

8. stakeholders and their concerns. The architecture description is required to include the

stakeholders for whom the description is produced and who the architecture is intended

to satisfy. It is also required to state “...the concerns considered by the architect in

formulating the architectural concept for the system.” At a minimum, the description is

required to address users, acquirers, developers, and maintainers.

9. viewpoints. An architecture description is required to identify and define the viewpoints

that form the views contained therein. Each viewpoint is described by its name, the

stakeholders and concerns it addresses, any language and modeling techniques to be used

in constructing a view based on it, any analytical methods to be used in reasoning about

the quality attributes of the system described in a view, and a rationale for selecting it.

10. views. Each view must contain an identifier or other introductory information, a

representation of the system (conforming to the viewpoint), and configuration

information.

2

Each box represents a concept, and each line represents an association between two concepts. Each

association has two roles—one in each direction— although both are not always depicted. The role

from A to B is depicted closest to B. Multiplicity is optional in this diagram; where identified, it

follows the UML convention, whereby 1 means one and 1..* means one or more. Stakeholders play

a key role; views conform to viewpoints that address stakeholders and their concerns.

System Architecture

Stakeholder

Architectural

Description

Concern Viewpoint View

has an

has 1..*

described by 1

identifies 1 ..*

is organized by 1 ..*

is important

is addressed to 1..*

to 1..*

selects

1..*

has 1..*

used to

cover 1..*

conforms to

10 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

11. consistency among views. Although the standard is somewhat vague on this point, the

architecture description needs indicate that the views are consistent with each other. In

addition, the description is required to include a record of any known inconsistencies

among the system’s views.

12. rationale. The description must include the rationale for the architectural concepts

selected, preferably accompanied by evidence of the alternatives considered and the

rationale for the choices made.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 11

4 Comparison

4.1 Comparing Definitions

We begin the comparison of V&B and 1471 by noting that 1471 defines architecture as the

fundamental organization of a system embodied in its components, their relationships to each

other and to the environment, and the principles guiding its design and evolution, where

• Fundamental organization means the essential, unifying concepts and principles.

• System may refer to an application, system, platform, system of systems, enterprise,

product line, and so on.

• Environment is developmental, operational, programmatic, or any other relevant context

of the system.

Although there are significant differences between that definition and the one underlying

V&B that was cited at the opening of this technical note, these differences do not represent

fundamental differences in philosophy. Both definitions emphasize structure. The V&B

definition goes further by explicitly recognizing multiple structures. The 1471 definition

goes further by including the environment and principles that spawned the structure(s) and

does not restrict its scope to software. The V&B definition uses the neutral term element and

eschewed component, which in some contexts refers explicitly to units of runtime interaction

(as opposed to development-time building).

4.2 Satisfying the Requirements of 1471 with V&B

Next, we list the requirements imposed by 1471 and explain how each one is satisfied by the

V&B approach.

12 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

Table 1: 1471 Requirements Satisfied by the V&B Approach

General Requirement Imposed by 1471 How the Requirement Is Achieved in the

V&B Approach

Identification and overview information.

This information includes a summary, a

context, a glossary, references, and a

change history.

Several items in this category amount to

good bookkeeping. Context is addressed in

the context diagrams; the other items are

prescribed in the templates described earlier.

Stakeholders and concerns. The standard

lists minimum examples that must be

addressed for both stakeholders and

concerns.

The documentation roadmap called for in the

“beyond views” template captures

information about stakeholders and their

concerns—specifically, how they will use the

documentation package. Make sure to

include users, acquirers, developers, and

maintainers.

Viewpoints. For each viewpoint, the

following must be specified:

• stakeholders addressed by the viewpoint

• concerns addressed by the viewpoint

• language, modeling techniques, or

analytical techniques to be used

• rationale for selection of the viewpoint

Any additional information such as

completeness and correctness checks,

evaluation criteria, heuristics, or guidelines

may be included.

Viewpoints correspond most closely to

architectural styles. A style is defined by the

elements, relations, and properties that

should be used in documenting a system

built using that style. By extension, a

viewpoint definition can be provided by a

style guide. A style guide defines the

elements, relationships, and restrictions

inherent in the style, and contains a section

noting what it’s for and not for (which should

help users in deciding what concerns will be

addressed), as well as a section on notations

and analysis techniques useful for working

with that style.

Views. Each view includes a representation

of the system in accordance with the

requirements of its viewpoint.

The view template defines the information

that should be documented for a view.

Consistency information. This information

includes a record of all the inconsistencies

among views, preferably accompanied by an

analysis of the consistencies among them.

The “documentation beyond views” part of

the package includes a mapping between

views.

Rationale. The rationale for the architectural

concepts selected and choices made,

preferably accompanied by evidence of the

alternatives that were considered.

Reserved spots for rationale are provided in

the view template and in the template for

documentation beyond views.

4.3 Discussion

We have seen that each requirement imposed by 1471 can be satisfied by the V&B approach

by imposing only very small additional conditions including

• complying with 1471’s minimum stakeholder list

• adjusting the documentation boilerplate to include the required identification and

overview information

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 13

• using style guides as the source of viewpoint definitions

In addition, the two approaches are conceptually compatible.

The approach implied by 1471 begins with stakeholders and their concerns. These concerns

are listed explicitly, and then viewpoints are crafted that (together) satisfy the stakeholders

and their concerns. Finally, the architecture is described using views based on those

viewpoints. Thus with the 1471 approach, we have

stakeholders/concerns Æ viewpoints Æ views

(The arrows mean “lead to.”) The approach espoused by V&B begins by aiming to document

those architectural structures that are actually present in the system, which come about as the

manifestation of the architect’s selection of styles with which to design the system.

Documenting a style as a view is done if the view has an important stakeholder/concern

constituency. Thus with the V&B approach, we have

structures/styles Æ chosen to document based on stakeholders/concerns Æ views

Thus, both 1471 and V&B will produce an architecture document that consists of a set of

views that satisfy the concerns of the architecture’s key stakeholders. Both approaches match

a set of stakeholders/concerns to a set of vocabularies (viewpoints or viewtypes/styles) to

select a set of views to document.

A more practical difference is that V&B provides more information and prescriptive

guidance, especially

• a reasonable starting set of views/styles to choose from with guidance about what each is

good for

• complete templates for an architecture document’s organization and contents

Finally, it is useful to discuss what V&B and 1471 have in common. First of all, both

exemplify the current approach to software architecture that eschews a fixed prescribed set of

views. Instead, both advocate building an architecture document out of those views that are

most useful for the job at hand. This choice depends on the stakeholders to be served by the

document and their concerns. Concerns include the achievement of specific quality

attributes.

Second, both 1471 and V&B place stakeholders in a position of prominence in the

architectural process. Unlike the classic (but naïve) idea that an architecture flows only from

a requirements document, we now recognize that architecture is the result of the blending of a

large number of forces and influences, many of which do not correspond to system

functionality. It is the responsibility of the architect to understand these forces and influences

and to track them down to their source—that is, to engage the stakeholders who hold them.

Both V&B and 1471 recognize the point made at the opening of this technical note:

Architecture design and documentation are activities in service of people.

14 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

References

URLs are valid as of the publication date of this document.

[Bass 03]

Bass, L.; Clements, P.; & Kazman, R. Software Architecture in

Practice, Second Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2003.

[Buschmann 96]

Buschmann, F.; Meunier, R.; Rohnert, H.; Sommerlad, P.; & Stal,

M. Pattern-Oriented Software Architecture, Volume 1: A System of

Patterns. New York, NY: Wiley, 1996.

[Clements 03]

Clements, P.; Bachmann, F.; Bass, L.; Garlan, D.; Ivers, J.; Little,

R.; Nord, R.; & Stafford, J. Documenting Software Architectures:

Views and Beyond. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2003.

[Hofmeister 00]

Hofmeister, C.; Nord, R.; & Soni, D. Applied Software Architecture,

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2000.

[IEEE 00]

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Recommended

Practice for Architectural Description of Software-Intensive

Systems (IEEE Std 1471-2000). New York, NY: Institute of

Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2000.

[Kruchten 95]

Kruchten, P. “The 4+1 View Model of Architecture.” IEEE

Software 12, 6 (November 1995): 42–50.

[Schmidt 00]

Schmidt, D.; Stal, M.; Rohnert, H.; & Buschmann, F. Pattern-

Oriented Software Architecture, Volume 2: Patterns for Concurrent

and Networked Objects. New York, NY: Wiley, 2000.

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017 15

16 CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE

Form Approved

OMB No. 0704-0188

Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching

existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding

this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters

Services, Directorate for information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of

Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503.

1. AGENCY USE ONLY

(Leave Blank)

2. REPORT DATE

July 2005

3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED

Final

4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE

Comparing the SEI’s Views and Beyond Approach for Documenting

Software Architectures with ANSI-IEEE 1471-2000

5. FUNDING NUMBERS

F19628-00-C-0003

6. AUTHOR(S)

Paul Clements

7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)

Software Engineering Institute

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, PA 15213

8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION

REPORT NUMBER

CMU/SEI-2005-TN-017

9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)

HQ ESC/XPK

5 Eglin Street

Hanscom AFB, MA 01731-2116

10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY

REPORT NUMBER

11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

12A DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Unclassified/Unlimited, DTIC, NTIS

12B DISTRIBUTION CODE

13. ABSTRACT (MAXIMUM 200 WORDS)

Architecture documentation has emerged as an important architecture-related practice. In 2002, researchers

at the Carnegie Mellon

®

Software Engineering Institute completed Documenting Software Architectures:

Views and Beyond (V&B), an approach that holds that documenting a software architecture is a matter of

choosing a set of relevant views of the architecture, documenting each of those views, and then documenting

information that applies to more than one view or to the set of views as a whole. Details of the approach

include a method for choosing the most relevant views, standard templates for documenting views and the

information beyond them, and definitions of the templates’ content. At about the same time, the Institute of

Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) was developing a recommended best practice for describing

architectures for software-intensive systems—ANSI/IEEE Std. 1471-2000. Like V&B, that standard takes a

multi-view approach to the task of architecture documentation, and it establishes a conceptual framework for

architectural description and defines the content of an architectural description.

This technical note summarizes the two approaches and shows how a software architecture document

prepared using the V&B approach can be made compliant with Std. 1471-2000.

14. SUBJECT TERMS

software architecture, architecture views, viewpoints, IEEE 1471,

viewtypes, views and beyond, architecture documentation,

architecture description, architecture representation, stakeholders

15. NUMBER OF PAGES

28

16. PRICE CODE

17. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION

OF REPORT

Unclassified

18. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF

THIS PAGE

Unclassified

19. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF

ABSTRACT

Unclassified

20. LIMITATION OF ABSTRACT

UL

NSN 7540-01-280-5500 Standard Form 298 (Rev. 2-89) Prescribed by ANSI Std. Z39-18 298-102