CAPRI MADDOX

GENERAL MANAGER

CLAUDIA LUNA

ASSISTANT GENERAL MANAGER

KIM KASRELIOVICH

ASSISTANT GENERAL MANAGER

CITY OF LOS ANGELES

CALIFORNIA

CIVIL + HUMAN RIGHTS

AND EQUITY DEPARTMENT

201 N. LOS ANGELES ST., SUITE 6

LOS ANGELES, CA 90012

______

(213) 978-1845

https://civilandhumanrights.lacity.org

KAREN BASS

MAYOR

March 8, 2023

The Honorable Karen Bass Honorable Members of the City Council

Mayor, City of Los Angeles c/o City Clerk

Room 303, City Hall Room 395, City Hall

RE: AN EQUITY ANALYSIS ON VIOLENCE AND CRIME FACING BLACK WOMEN AND

GIRLS IN THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES.

SUMMARY

On May 24, 2022, the City Council instructed (CF:22-0102) the Civil, Human Rights, and Equity

Department (LA Civil Rights) to report back with an equity analysis on the violence and crime

that Black women and girls experience in the City of Los Angeles. The following report is a

direct response to the instructions, and expounds on the topic through 1) an analysis of the

rates at which homicides and violent crimes against them are solved, 2) an assessment of how

cases of missing Black women and girls are managed, and 3) policy recommendations to

improve equity and justice for victims and their families.

This report recognizes the growing epidemic of violence against women — specifically against

women of color and Black women — and acknowledges that there is opportunity to bolster

safety and stability measures for communities most impacted by violence. Therefore, this report

is mapped through the following six action items:

● Provide a background of this work, including a brief note on the murder of Tioni Theus;

● An exploration of Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) data;

● A brief survey of positive and negative media impact and influence;

● Include salient notes from discussions with community-based organizations involved in

this work;

● Identify challenges in writing this report; and

● Provide recommendations for solutions and next steps.

In summary, our statistical analysis found that:

● Although overall violent crime rates have decreased in the City of Los Angeles over a

ten-year period, the number of Black women experiencing violence has remained at a

steady high if not increased.

○ Although Black women comprise approximately 4.3% of the City of Los Angeles

population, they often make up approximately 25% to 33% of victims of violence.

● Black and Hispanic women saw a slight uptick in domestic violence (DV) from 2020 to

2021.

○ Between 2016-2021, Black women saw an average yearly increase of 4.09% DV

aggravated assault reports. The LAPD 77th, Southeast, Southwest, Newton, and

Central divisions were the most frequently listed in the data.

● From 2011-2022:

○ Black women accounted for approximately 32.85% (158) of female homicides

and nearly one-third (28.5%) of all missing women in the City.

○ Hispanic women made up approximately 42.8% of female homicides and 36.7%

of missing women from the last two years.

○ All non-Black and non-Hispanic women made up approximately 24.3% of female

homicides.

■ White women made up approximately 18% of female homicides and

20.3% of all missing women.

○ 130 missing women were listed as an “Unknown” racial demographic.

● Data from LAPD divisions and the LA Civil Rights Department L.A. REPAIR Zones

demonstrate that communities with the highest poverty, unemployment, and

environmental hazards experience higher rates of violence against women.

● Gaps in data collection do not easily enable law enforcement to capture crime trends

facing Angelenos with intersecting identities, such as Black women, potentially obscuring

the local impact of what the United Nations has called a “shadow pandemic” of violence

against women.

● Demonstrable disparities exist in media coverage and characterization of the murders of

Black women, compared to their non-Black, non-Hispanic counterparts.

● Measuring one month from the date of her murder by setting database search

parameters to “Location by Publication: California,” a search for “Tioni Theus” yielded

just eight results (January 8, 2022 to February 8, 2022). The same parameters applied to

a search for “Brianna Kupfer” yielded 25 results (January 13, 2022 to February 13,

2022).

● Community-based organizations consistently encounter funding barriers that present

significant challenges to continuing long-term holistic services to survivors of violence

and their families.

● Community programs must be undergirded by policy and legislative action at all levels of

government.

● Prevention programs such as youth development training and leadership activities can

be highly beneficial in decreasing rates of violence.

RECOMMENDATIONS

● Invest in prevention programming and support strategies to mitigate risk of violence and

decrease incidents of violence against women of color

● Increase survivor-focused education and training to support the long-term health of

survivors and decrease risk of violence for responders answering domestic violence calls

2

● Explore how funding is allocated to community organizations, where barriers to access

such funding programs exist, and how such restrictions and barriers may be removed to

ensure the longevity of life-saving programs and resources

● Upgrade data collection systems and methodologies for data classifications in order to

increase the speed of analysis and support rapid response to families in crisis

● Determine avenues for accelerating City policy and campaigns to address additional

components of violence mitigation and prevention, such as alternatives to police

response to domestic violence calls, policies which support the economic stability of

Black women and women of color, and educational campaigns with community partners

to decrease stigma and increase awareness.

For a more thorough discussion of recommendations and proposed policy actions to mitigate

violence against Black women and women of color in general, please see the

“Recommendations” section at the end of this report.

BACKGROUND

On January 8, 2022, Tioni Theus, a 16-year-old Black girl, was found dead on a 110 Freeway

on-ramp. Reporting by the Los Angeles Times indicates that almost two weeks passed before

officials called for public assistance in finding her killer in hopes of bringing justice to Theus’s

family. Recent articles share that more than a year later, there has been no progress in this case

and her family continues their plea for support.

1

As addressed in the instructing City Council motion, this incident — while a deeply tragic act of

violence — is not a unique story in the City of Los Angeles, or in the United States overall.

Women of color experience increased risk of harm and violence as a result of systemic violence

which offers them little to no support or room for upward mobility. Black women experience a

unique position of precarity as a result of decades of discrimination, grounded both in racism

and sexism. These factors of risk are compounded as women of color, and Black women in

particular, navigate financial instability, income inequality, housing insecurity, and a myriad of

other potential social safety risks.

These intersecting factors lead to repeated disproportionate trends of violence. Such trends

were not only exposed, but exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic when rates of violence

against women, especially in domestic and/or private spaces with intimate partners, went up

substantially. This is what the United Nations has dubbed “The Shadow Pandemic.”

2

News

outlets found that women’s advocacy groups and those supporting survivors of domestic

violence received a significant increase in calls for assistance during the pandemic.

3

3

Whitfield, Chandra Thomas. “The Pandemic Created a ‘Perfect Storm’ for Black Women at Risk of

Domestic Violence.” MIT Technology Review. MIT Technology Review, September 29, 2022.

2

“The Shadow Pandemic: Violence against Women during Covid-19.” UN Women – Headquarters.

https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/in-focus-gender-equality-in-covid-19-response/violen

ce-against-women-during-covid-19.

1

Pulliam, Tim. “1 Year after Teen Was Killed, Found Dead on Side of 110 FWY, Family Continues to Seek

Justice.” ABC7 Los Angeles. KABC Television, January 8, 2023.

https://abc7.com/tioni-theus-1-year-later-reward-2023-teen-girl/12673710/.

3

Furthermore, research suggests that issues such as housing instability, lack of digital and

technological access, and a reliance on Black women to act as the primary economic provider

created additional burdens and risks during the pandemic which in turn confounded and

increased the likelihood of experiencing violence.

4

Incidents, such as the murder of Tioni Theus, therefore, are part of a larger system of violence

that Black women and women of color navigate daily. In this report, we first attempt to articulate

what is meant by our use of the word “violence.”

ACTION PLAN DEVELOPMENT AND METHODOLOGY

Defining Violence

The term “violence” generally connotes an image of graphic brutality leading to injury and/or

death. Useful as it may be for conjuring a similar understanding across audiences, “violence” is

too broad of a word when attempting to analyze the different types of harm and risk to which

women of color are exposed. Bearing this in mind, LA Civil Rights determined the following six

types of violence are strong, salient starting points for this conversation: assaults (particularly as

they relate to domestic violence and intimate partner violence), rape, acts of hate, homicide and

aggravated assault, battery, and disappearances or instances in which women have gone

missing.

These typologies are not meant to provide a complete picture of the many areas of violence that

women of color experience throughout their lives. Instead, these categorizations serve as an

opportunity to engage with data that captures acts of violence that are most likely to impact

women as a direct result of underlying sexist and/or racist biases against women.

It is imperative to note that despite our best attempts to define a baseline for the most salient

types of violence that women of color experience, there are two components to violence that are

overshadowed by the apparent types of violence listed above. First, the psychological toll of

violence must be addressed. It should be acknowledged and honored that women, particularly

women of color, Indigenous women, and Black women have developed a set of personal and

communal skills to not only limit their exposure to violent acts against their personhood, but to

merely survive.

A 2016 Gallup poll found that one in three women “frequently or occasionally” worry about being

sexually assaulted.

5

In comparison, the poll found that only one in 20 men felt the same.

5

Jones, Jeffrey M. “One in Three U.S. Women Worry about Being Sexually Assaulted.” Gallup.com.

Gallup, March 1, 2022.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/196487/one-three-women-worry-sexually-assaulted.aspx.

4

Willie, Tiara C. Rep. Understanding and Addressing COVID’s Impact on Housing Among Black IPV

Survivors. Ujima, Inc.: The National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black Community,

2020.

https://americanhealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/website-media/resources/COVID%20Impact%20

on%20Housing%20Report.pdf.

https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/09/28/1060057/pandemic-black-women-domestic-violen

ce/.

4

Additionally, RAINN (the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) reports that one in six

American women will experience assault in her lifetime. For Black women, the likelihood

increases to one in five. Indigenous women disproportionately face extremely high levels of

violence. A 2013 fact sheet from the National Congress of American Indians Policy Research

Center stated that roughly one in three American Indian and Alaska Native women will be

raped.

6

With a broadened scope of labeling the likelihood of violence against women, approximately

one in three women will suffer some form of violence by an intimate partner. In the United

States, this translates to approximately 61 million women overall.

7

In addition to the fear of

violence looming large for many women as odds increase, there are a number of mental health

impacts associated with experiencing some form of intimate partner violence. The Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that:

“survivors can experience mental health problems such as depression and PTSD

symptoms. They are at higher risk for engaging in behaviors such as smoking, binge

drinking, and sexual risk activity. People from groups that have been marginalized, such as

people from racial and ethnic minority groups, are at higher risk for worse consequences.”

8

Furthermore, survivors can experience a number of physical health impacts including: “a range

of conditions affecting the heart, muscles and bones, and digestive, reproductive, and nervous

systems, many of which are chronic.”

9

As such, it is evident that survivors of violence

experience both physical and mental health impacts long-after they have escaped incidents of

violence.

The second component of violence that is less apparent, but nevertheless significant, is the

pernicious role of societal attitude and state institutions. In other words, women, with particular

consideration for women of color, Indigenous women, Latina/x/e women, and Black women,

have been historically limited in their ability to create safety nets for themselves as a result of

racism and sexism.

10

Underscoring these histories of economic inequality – which have continued up to the

contemporary moment – can lead to potential explanations for why women have fewer

10

Davis, Angela. “The Color of Violence against Women.” The Color of Violence Against Women.

ColorLines Magazine, September 29, 2000. http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/582.html.

9

“Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence | Violence Prevention | Injury Center | CDC.” Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention.

8

“Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence | Violence Prevention | Injury Center | CDC.” Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention.

7

“Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence | Violence Prevention | Injury Center | CDC.” Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 11,

2022. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html.

6

Rep. Policy Insights Brief Statistics on Violence Against Native Women. National Congressional

American Indians , February 2013.

https://www.ncai.org/attachments/PolicyPaper_tWAjznFslemhAffZgNGzHUqIWMRPkCDjpFtxeKE

UVKjubxfpGYK_Policy%20Insights%20Brief_VAWA_020613.pdf.

5

opportunities to safely thrive when leaving intimate partners who are violent, or to easily remove

themselves from violent situations. Public LAPD web pages align with this explanation as well,

as they write that the survivor “may be economically dependent on the batterer.”

11

Academic

research also supports this assertion. A 2010 paper reported that “women with annual income

below $10,000 report rates of domestic violence five times greater than those with annual

income above $30,000 (Bureau of Justice Statistics 1994).”

12

Survivor-focused policy practices

that aim to prevent, end, and/or limit exposure to violent situations must be linked to social and

economic policies which support the long-term stability, independence, and upward mobility of

marginalized communities.

Violence against women, and thus the disproportionate rate of violence against women of color,

is an issue that cannot be hidden or relegated to the domestic sphere. Sworn to establish

justice, it is incumbent upon the state — at all levels of governance — to take measures which

can reduce the rates of violence and provide justice, healing, and relief to survivors of violence

and their loved ones as well as the families and communities of women who have been

murdered or are missing.

13

Research and Landscape Analysis

In order to address these issues and seek active solutions, LA Civil Rights developed a

three-part review which addressed the original intent of this motion and used these findings to

host conversations with community organizations playing a significant role in survivor care,

community healing, and violence prevention.

LA Civil Rights first conducted extensive background research to determine what data sets

already existed in academic journals, official publications, and governmental reports.

Additionally, the Department examined local media publications to understand existing

community discourse, particularly as it relates to the lived experiences, narratives, and

anecdotes provided by women of color. Lastly, the Department met with three community based

organizations that provide services and programs to women who experience violence to

understand how their work can inform the City’s approach to address this crisis. These findings

provided the foundation for analysis.

Internal and External Stakeholder Engagement:

After examining existing literature, LA Civil Rights coordinated with the Los Angeles Police

Department (LAPD) to gather quantitative information and review salient trend lines.

13

Petrosky, E., Blair, J. M., Betz, C. J., Fowler, K. A., Jack, S. P. D., & Lyons, B. H. "Racial and Ethnic

Differences in Homicides of Adult Women and the Role of Intimate Partner Violence - United

States." July 21, 2017. 2003-2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 66(28),

741–746. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6628a1

12

Aizer, Anna. “The Gender Wage Gap and Domestic Violence.” The American Economic Review 100,

no. 4 (2010): 1847–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27871277.

11

“Domestic Violence: Reasons Why Battered Victims Stay with the Batterers.” LAPD Online. Los

Angeles Police Foundation , February 9, 2022.

https://www.lapdonline.org/domestic-violence/domestic-violence-reasons-why-battered-victims-st

ay-with-the-batterers/.

6

LA Civil Rights then sought to understand how media representation worked as a key variable in

addressing violence and the disproportionate impacts that particular communities navigate. The

Department utilized LexisNexis as well as Boolean searches to highlight the role of news outlets

and media coverage of the crimes or pursuit of perpetrators of crimes against women in

general, women of color, and more specifically, Black women.

Community conversations served as important additions to anecdotal evidence, and

underscored the incalculable value of local organizations contributing to healing and survivor

safety. Notes and recurrent themes in these conversations were used in conjunction with

quantitative data to demonstrate the disproportionate impacts of violence against Black women

and women of color, as well as to inform relevant recommendations at the end of this report.

Table 1: Internal and External Participants

Internal Accountability Partners

External Accountability Partners

● Los Angeles Police Department

● Peace Over Violence

● Women Against Gun Violence

● Jenesse Center

Collected Data

In order to address the broad and pervasive issue of violence against women, LA Civil Rights

focused this report on six types of violence [defined by LAPD classification]:

● Domestic Violence (Aggravated and Simple Assaults)

● Rape I & II

● Hate Crimes

● Homicide and Aggravated Assault

● Battery

● Missing Persons

The following sections of this report are dedicated to highlighting important data points about

rates of violence against women of color, with particular consideration for Black women given

the specific nexus of intersecting risks that they face.

7

Domestic Violence (Aggravated and Simple Assaults)

This category of data captures assaults (aggravated and simple) which are classified as

domestic violence incidents. California law requires that responses to domestic violence calls

result in a mandatory arrest.

14

As explained by the LAPD, survivors may attempt to recant a

statement or ask officers to not make an arrest, but the law requires that an arrest be made.

Between January 2011 through August 2022, there were 175,624 total domestic violence (DV)

victims in the City of Los Angeles, 79% (138,212) of which were female.

● Black women, although only accounting for roughly 4.3% of the City’s population, were

23.12% of all DV victims (40,597 individuals) and 29.37% of female DV victims.

15

● Hispanic women account for 24.2% of the City’s population, but approximately 50.5%

(69,836) of female DV victims.

16

● In stark contrast, white non-Hispanic women, accounting for approximately 14.05% of

the City, were only 12.7% of the female DV victim population.

17

Even in disaggregating aggravated and simple assaults, Black women were still

disproportionately overrepresented in the data. From January 2011 to August 2022, there were

27,357 total DV aggravated assault victims. Black women were 25.14% (6,878) of these victims.

Similarly, there were 148,267 victims of simple assault. Black women were 22.74% (33,719) of

these victims.

DV rates have declined in recent years, but Black and Hispanic women saw a slight uptick in

violence from 2020 to 2021. Between 2016-2021, Black women saw an average yearly increase

of 4.09% DV aggravated assault reports. In general, Hispanic women were the most common

victims of domestic violence, while Black women were consistently the most overrepresented

population as illustrated in Graph 1 below.

With regards to geographic distribution, the 77th, Central, Newton, Southeast, and Southwest

divisions were the most frequently listed in the data. The 77th, Central, Southeast, and

Southwest divisions correlate with the established Los Angeles Reforms for Equity and Public

Acknowledgment of Institutional Racism (L.A. REPAIR) Zones.

For a more thorough discussion of the importance of the correlation between frequently listed

LAPD divisions and L.A. REPAIR zones please see the “Overall” portion of the “Research and

Landscape Analysis” section.

17

“U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts: Los Angeles City, California.” U.S. Census Bureau.

https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/losangelescitycalifornia.

16

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Los Angeles City, California.” U.S. Census Bureau.

15

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Los Angeles City, California.” U.S. Census Bureau.

14

Rep. Domestic Violence Guidelines. California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training,

February 2023. https://post.ca.gov/Portals/0/post_docs/publications/Domestic_Violence.pdf.

8

Graph 1

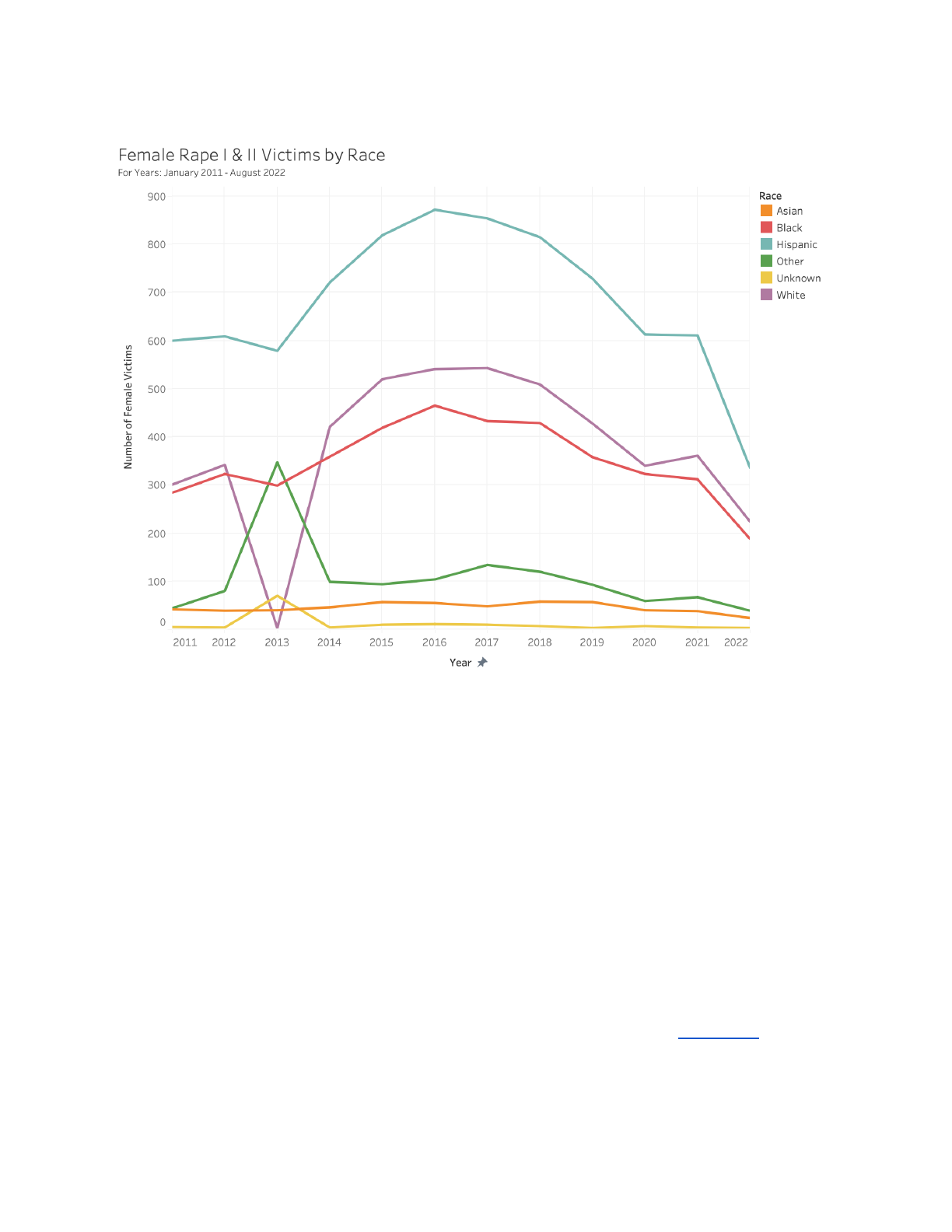

Rape I & II

In 2013, the Federal Bureau of Investigation rewrote the definition of rape - removing the use of

the word “forcible” - to become the following: “The penetration, no matter how slight, of the

vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another

person, without the consent of the victim.”

Using 2011 as a baseline, the number of Black women reporting rape from 2012 to 2022 has

increased in the City of Los Angeles. In 2016, the number of incidents reported peaked at 465,

averaging to approximately 1.3 women reporting an incident of rape every day.

Overall, there were 18,845 female rape victims from January 2011 to August 2022 in the City of

Los Angeles. Black women accounted for 22.24% (4,192) of all female rape victims in the city. In

the 77th Division alone, Black women accounted for 55% (815) of female rape victims. Similarly,

Black women accounted for 51.3% in the Southeast Division and 44.4% in the Southwest

Division.

9

Graph 2

Hate Crimes

The Los Angeles Police Department only recently began collecting data that specifically

captures the number of hate crimes and hate incidents in the City of Los Angeles. As such, data

only captures crimes from January 2018 to August 2022. This limited time frame means that

findings and results are limited. However, it is notable that hate crimes committed with an

anti-Black bias made up 23.13% of all hate crimes reported. Hate crimes committed with an

anti-female bias made up 0.55%.

Hate crimes have consistently increased each year in the City of Los Angeles for at least the

last seven years. This is due to a number of factors, including but not limited to, increased

polarization in national politics, increasing online radicalization of people, furthered by false and

misleading media, and internationally traumatizing events such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Local increases may also be spurred by a recent increase in reporting following widespread

efforts to promote hate crime and hate incident reporting, such as the LA For All campaign

launched in 2021.

10

Similarly, the data does not account for hate crimes committed on multiple biases. For example,

while the data can provide insight on anti-Black hate crimes or anti-female hate crimes, the

intersection of race and gender is not accounted for. Therefore, as a result of methods for

categorization and classification of hate crimes, there are gaps in the data that prevent clear

analysis illustrating the rate that Black women experience hate-based violence.

Homicide and Aggravated Assault

As with data specific to domestic violence, the rates of homicide and aggravated assault

revealed disproportionately high rates of violence against Black women. From January 2011 to

August 2022, there were a total of 481 female homicides in the City of Los Angeles. Black

women represented 32.85% (158) of female homicides as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Although the number of Black female homicide victims in 2011 (16) is identical to the number in

2022 (also 16), the year over year fluctuation reveals drastic spikes and drops. For example,

although the number of Black female homicide victims dropped from 2016 to 2017 (11 to eight),

it sharply spiked in 2018, rising to 19 Black female homicide victims in the City of Los Angeles.

This number peaked in 2021 with 20 Black female homicide victims. The number of Hispanic

female homicide victims peaked in 2021 as well, totaling 26 victims. Together, Black and

Hispanic female homicide victims represented approximately 80% of all female homicide victims

that year. Hispanic women saw the highest number of female homicide victims (except for 2011

and 2012) per year; however, Black women were statistically the most overrepresented

demographic within the data set.

Table 3

11

Graph 3

The University of Illinois Chicago reported that “murder by intimate partners is among the

leading cause of death among” Black women ages 15 to 45 across the United States.

18

Furthermore, compared to other women, Black women are three times more likely to be killed by

a partner.

19

From January 2011 to August 2022, there were 62,264 female victims of aggravated assault in

the City of Los Angeles. The female aggravated assault rates increased at a rate of 9.21%

annually. From January 2011 to August 2022, Black women were 35.76% (22,267) of the

victims.

Black women comprised more than one third of all female aggravated assault victims over the

last decade, while Hispanic women made up nearly half (January 2011 – August 2022).

19

Hampton, Dr. Robert, Joyce Thomas, Dr. Trisha Bent-Goodley, and Dr. Tameka Gillum Gillum. Rep.

Facts about Domestic Violence & African American Women. St. Paul, MN: Institute on Domestic

Violence in The African American Community, 2015.

http://idvaac.org/wp-content/uploads/Facts%20About%20DV.pdf.

18

“Women's Leadership and Resource Center.” Domestic Violence against Black Women. Women's

Leadership and Resource Center | University of Illinois Chicago. https://wlrc.uic.edu/bwdv/.

12

Specifically from 2016 to 2021, Black women saw an average annual increase of 3.44% in

aggravated assaults. Hispanic women saw an average annual increase of 4.20%.

Table 4

Battery

From January 2011 to November 2022, the number of Black female battery victims has

decreased. However, cases of battery against Black female victims were most frequent in the

following LAPD divisions: 77th, Southwest, Southeast, Central, and Newton.

In examining all reports of battery from January 2011 to November 2022, Black women

represented 14.72% (32,179) of all victims in the City of Los Angeles. When filtering only for

Black victims, Black women were approximately 62.44% of the population. Likewise, when

filtering only for female victims (110,456), Black women represented 29.13% of the population.

Overall, although Black women are disproportionately represented in the victim population, the

proportion of Black female battery victims has decreased over time. From January 2011 to

November 2022, Black women represented 29.13% of the female (110,456) population. In

contrast, from 2016 to 2021, Black women averaged 25.39% of the female victim population as

shown in Graph 4.

(This space intentionally left blank)

13

Graph 4

Missing Persons

In the City of Los Angeles there remain 179 open and active missing persons cases from

January 2010 through December 2019; 48 of the persons are female and 14 of them are Black

women.

In the last two years (2021-2023), Black women accounted for nearly one-third (28.5%) of all

missing women in the City of Los Angeles.

In 2021 specifically, there were 3,879 adults (1,552 women) reported missing in the City. Black

women were 11.6% of all missing persons, and 28.9% of missing women. Similarly, in 2022,

there were 907 missing persons. Black women (253 missing) made up 11.2% of all missing

persons and 27.9% of missing women.

LA Civil Rights was not able to acquire data from cases prior to 2021. The LAPD reported that

“prior to 2021, the Department did not collect data on the demographics of reported missing

persons related to gender, age, ethnicity.” The Department used the Detective Tracking Case

System (DCTS) which only captured the name, report date/time, and location. Therefore, the

14

LAPD reported that “a request for any data outside of what DCTS tracks would have to be done

manually.”

Clearance Rates

Clearance rates in the City of Los Angeles as well as at the state and federal level are

frequently organized by perpetrator demographics. In this sense, locating data on the clearance

rates of crimes committed by a particular demographic is far easier than locating data on

clearance rates of cases that are categorized by the demographic of the victim.

This perpetrator-focused method of data collection results in an unclear understanding of

clearance rates of crimes committed against particular victim demographics, and therefore,

community-specific solutions may remain elusive.

As such, publicly available data is limited. One five-year data set from 2016-2022 highlights that

77 out of 81 homicide cases with Black female victims were cleared.

20

The shortest time period

between date occurred and date of clearance was one day (2022) while the longest was 222

days (2018-2019).

This data point, while useful for examining this particular snapshot of data, cannot accurately

provide context for comparative analysis.

Overall

The data yielded indicates that Black women are consistently overrepresented in the victim

population. Although Black women are only 4.3% of the population in Los Angeles, they often

comprise a quarter to a third of victims. For example, when examining aggravated assault data,

Black women represented 22,267 reports out of 62,264 total reports. Black women were 1.9

times as likely to be victims of aggravated assault compared to their non-Black, non-Hispanic

counterparts. As such, although certain data sets may demonstrate a decrease in the number of

victims over a ten-year period, the number of Black women experiencing violence has increased

over time and at best, held at a steady high.

When speaking to how cases are organized and handled, the LAPD told LA Civil Rights that

cases are not prioritized or handled differently as a result of the victim’s race, gender, or other

personal identity. This is in line with the legal requirements of approved California Proposition

209 (November 1996). As such, the LAPD is not legally allowed to “grant preferential treatment

on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public

employment, public education, and public contracting.”

21

Therefore, the LAPD cannot legally

prioritize cases on the basis of a victim's personal identity.

21

“California Proposition 209, Affirmative Action Initiative (1996).” Ballotpedia. Ballotpedia.

https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_209,_Affirmative_Action_Initiative_(1996).

20

LAPD Public Records & Subpoena Response Section, CPRA Unit, "Request 22-8752: FEMALE

BLACK HOMICIDE VICTIMS 2018-2022." Los Angeles, CA: City of Los Angeles Public Record

Request, October 18-24, 2022

15

In summation, the data confirms what many already know to be true: Black women experience

violence at disproportionately higher rates compared to their white female counterparts.

Therefore, proper attention and vigilance must be dedicated to supporting and uplifting the

stories of these survivors, victims, and their families.

Additionally, the overlay of violence in communities that are at increased risk of social and

economic instability cannot be ignored. As previously articulated, four LAPD divisions overlap

with five LA REPAIR Zones, which is illustrated in Table 5 and Map 1.

The L.A. REPAIR Zones represent nine communities across the City of Los Angeles highlighted

as areas that are most impacted by institutional, systemic racism. These Zones were created as

part of the L.A. REPAIR Innovation Fund, which allows community participants to take on an

active role in the allocation of millions of City dollars to community organizations via direct

grants and the participatory budgeting process. The L.A. REPAIR program represents the first

participatory budgeting program in the history of the City of Los Angeles, and will allot $8.5M

across the nine Zones. Furthermore, LA Civil Rights has allocated $2M from the fund to create

nine Peace and Healing Centers, operated by community based organizations, in REPAIR

Zones to address social, economic, and environmental healing.

These nine Zones were selected using Community Planning Areas (CPAs) that have a high

percentage of people of color and a high share of the population who live below the poverty line.

Selected indicators revealed that these nine communities sit at the intersection of race and

poverty — where the legacy and consequences of structural and institutional racism are evident

in the City of Los Angeles.

Explained earlier in this report, women of color face particular social and economic challenges.

This is especially true for women of color who are also the financial head of household. There is

a clear correlation between low annual income and higher rates of domestic violence. As such,

it follows that L.A. REPAIR Zones — which see disproportionately high rates of poverty — would

overlap with LAPD divisions which reported higher rates of violence, particularly against women

of color and Black women. Seeing this correlation, the City of Los Angeles has an incentive to

take action to support these communities by:

● Increasing upward mobility programming and economic opportunities;

● Investing in social safety net programs which can act as social and economic protection;

and

● Leveling the socioeconomic playing field by requiring businesses to pay a living wage

and support economic policies which allow for increased quality of life.

(This space intentionally left blank)

16

Table 5: REPAIR Zone & LAPD Division Correlation

REPAIR Zone

LAPD Division

● Skid Row

● Central Division

● South L.A.

● 77th Division

● South L.A.

● West Adams - Baldwin Village - Leimert

Park

● Southwest Division

● Southeast L.A.

● Southeast Division

Map 1: L.A. REPAIR Zones Across 4 LAPD Divisions

Confounding Factors and Challenges

As previously noted, there may be a number of confounding factors which distort and influence

the LAPD data.

First, these figures (specifically those focusing on battery, rape, and domestic violence) do not

likely represent all cases of violence against women, women of color, and Black women in the

City of Los Angeles. Hesitation based on fear of retaliation, or lack of knowledge on rights or

17

how to report could likely translate to a far greater number of instances of violence. Similarly, a

distrust in the government and/or law enforcement officers may mean that victims of violence

are less likely to come forward and report abuse.

22

An important example can be found in examining the rates of reported incidents of rape. As

previously articulated, in the City of Los Angeles there were 4,192 Black female rape victims,

which represents approximately 22.24% of all female rape victims. On the national level,

advocacy nonprofit organization Color of Change reported that approximately 20% of Black

women will experience sexual violence.

23

Despite these already high rates of violence, Color of

Change reported that for every Black woman who files a report with law enforcement, at least

15 incidents will go unreported.

24

Low reporting rates are a national issue. RAINN reports that an American is assaulted

approximately every 68 seconds.

25

The national reporting averages do not match this. Similarly,

the Brown Political Review reported that only 54% of domestic violence incidents will be

reported to law enforcement.

26

On college campuses, estimates suggest that only 12% of

incidents will be reported. While decreasing the stigma in sharing stories of survivorship can

improve reporting rates, data collection will likely present a persistent challenge as not all

survivors will feel comfortable or safe to report incidents of violence.

Secondly, as noted in the section on hate crime data, some sections of data may be skewed to

show an increase over time due to increases in general education on reporting and the rights of

victims. More research should be done to understand how educational community programs

could affect data sets.

Thirdly, the 77th, Southeast, Southwest, Newton, and Central Divisions were reported to see

disproportionately higher rates of violence as compared to other divisions. These numbers have

been skewed as well since Domestic Abuse Response Teams (or DART programs) operate in

all divisions, except for the Central Division.

27

Therefore, if the DART program were expanded to

include more divisions then there may be a more equal distribution of incidents and cases.

In addition to potential confounding variables, there were a few challenges in the data collection

process.

27

“Domestic Abuse Response Team (DART).” Safe LA, 2009. https://www.safela.org/about/dart/.

26

Hodges, Claire. “From Abuse to Arrest: How America's Legal System Harms Victims of Domestic

Violence.” Brown Political Review, August 23, 2021.

https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2021/08/abuse-to-arrest/.

25

“Scope of the Problem: Statistics.” RAINN. https://www.rainn.org/statistics/scope-problem.

24

“Mass Media Is Complicit in Misogynoir and Rape Culture. Demand That Media Outlets

#Protectblacksurvivors from Undue Harm and Commit to Better Reporting!” ColorOfChange.org.

23

“Mass Media Is Complicit in Misogynoir and Rape Culture. Demand That Media Outlets

#Protectblacksurvivors from Undue Harm and Commit to Better Reporting!” ColorOfChange.org.

https://act.colorofchange.org/sign/protect-black-survivors?source=coc_main_website.

22

Hampton, Dr. Robert, Joyce Thomas, Dr. Trisha Bent-Goodley, and Dr. Tameka Gillum Gillum. Rep.

Facts about Domestic Violence & African American Women.

18

The LAPD reported to LA Civil Rights that the majority of these data sets had to be put together

manually by officers; thus there was a significant time delay in reporting as officers did not have

adequate and up-to-date tools at their disposal to pull these numbers quickly. This can result in

a delay in reporting and analysis which could contribute to limited institutional and public

awareness of this issue, keeping women of color suffering unseen.

Additionally, an intersectional lens was not easily employed. Data sets, such as the hate crime

data, do not allow for intersectional analysis as cases are classified by one bias type. Therefore,

hate crimes against an individual due to multiple biases are not accurately captured. In the case

of this report, for example, capturing the number of hate crimes that were committed against

Black women due to their racial and gender identity is not possible.

These data blindspots are not unique to the LAPD. This issue is seen in federal reports (both

those developed through aggregation of local data and national surveys) as well, where

identifying the number of victims (or survivors) by the intersection of identities such as race and

gender identity is not available. This also puts women of color at risk as their stories are not

captured in data sets and therefore the pervasive issue of violence against women of color, and

particularly Black women, is obscured.

A focus on overall trends, while valuable for understanding community risk and the general rise

and fall of violence rates, does not highlight the specific positions of violence that women of

color navigate if it does not allow for the disaggregation of race or gender nor the incorporation

of an intersectional analysis. Furthermore, without governmentally-sponsored research and

literature to provide quantitative foundations for these stories, the narratives and lived

experiences of Black women and women of color are left unjustified and often ignored.

Finally, it must be noted that the data provided by LAPD interchangeably uses the terms

“female” and “woman” when discussing issues that disproportionately affect particular

populations. For the purposes of this report, LA Civil Rights has chosen to use the words

“woman” and “women” as it allows for more inclusive language. However, this discrepancy in

terminology potentially obscures the violence that transgender women face if they are

misgendered and/or incidents of violence against them are misclassified.

MEDIA ANALYSIS

Considering that this Council motion began as an attempt to answer a call for justice for Tioni

Theus, it is relevant to consider how the media (both traditional news outlets and social media)

play a role in this issue.

Traditional News Media

By conducting Boolean searches in the LexisNexis database, it became clear that a large

number of stories on Tioni Theus focused on questions of her actions, insinuating that “theft and

prostitution” could have played a role.

28

While her family came forward with stories saying that

28

“'We Have so Many Questions;' Family of Tioni Theus, Teen Found Dead on Side of Freeway,

Demands Answers.” CBS News. CBS Interactive, January 24, 2022.

19

they intended to “humanize her”, the media’s attention to such details led to connotations of

victim-blaming. Similarly, on January 13, 2022,

29

the tragic and brutal murder of UCLA student

Brianna Kupfer, a white woman, took place.

30

The news stories that focused on her addressed

the incident and the violence that took place, but did not share personal background or

assumptions about her state of mind in conjunction with her death.

This slanted narrative is all too common when it comes to the discussion of Black women,

especially Black girls, in the media. Referred to as the “adultification” of young Black girls, this

often means that the media and general public does not allow young Black girls to be seen as

youthful, but instead treats them as if they are older, more mature, and capable of greater

agency — and greater share of the blame.

31

This causes three simultaneous issues:

● Desensitize viewers to violence against Black women and girls;

● Affect public perception of violent crime and its correlation to potential punishment; and

● Retraumatize Black communities and families who must repeatedly combat this

narrative.

These imbalanced reporting mechanisms and the unconscious bias of the media is evident in

the coverage of violence occurring in the City of Los Angeles. Basic Google searches yielded

important differences.

As of January 30, 2023, a Google search for “Tioni Theus” resulted in 53,900 hits. In contrast, a

Google search for “Brianna Kupfer'' resulted in 480,000 hits. A LexisNexis search exploring this

found similar results. Measuring one month from the date of their murders and limiting results to

“Location by Publication: California,” a search for “Tioni Theus” yielded 8 results (January 8,

2022 to February 8, 2022). In contrast, the same parameters applied to a search for “Brianna

Kupfer'' yielded 25 results (January 13, 2022 to February 13, 2022). This indicates that in the

first 30 days after their murders, news outlets reported on Kupfer three times more frequently

than they reported on Theus.

The trend holds true statewide. A LexisNexis audit in February 2023 using the search string

“Black Women AND Violence OR Murder OR Missing OR Death” and narrowing the results to

“Location by Publication: California” from January 01, 2013 to January 01, 2023 yielded 1,166

31

Epstein, Rebecca, Jamilia J Blake, and Thalia González. Rep. Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of

Black Girls’ Childhood. Washington D.C, D.C: Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality,

2017.

30

Winton, Richard, and Nathan Solis. “UCLA Student Brianna Kupfer Stabbed 26 Times in Deadly

Hancock Park Attack, Autopsy Shows.” Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, August 3, 2022.

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-08-02/ucla-student-brianna-kupfer-stabbed-26-time

s-autopsy-shows.

29

Solis, Nathan. “Employee Stabbed to Death at Hancock Park Furniture Store.” Los Angeles Times. Los

Angeles Times, January 14, 2022.

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-01-14/employee-stabbed-to-death-at-hancock-park-

furniture-store.

https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/we-have-so-many-questions-family-of-tioni-theus-tee

n-found-dead-on-side-of-freeway-demands-answers/.

20

results. The same parameters applied to the search string “White Women AND Violence OR

Murder OR Missing OR Death” found 490 results.

When considering discussions of violence against women in general, research suggests that

such incidents are reported as singular and/or random, episodic events, which ignores histories

of rape culture, the normalization of violence against women, and the frequency that women,

particularly women of color, experience gender-based violence. A UN Women report found that

the “level of sensationalism or ‘shock value’ in the case determines its ‘newsworthiness’.”

32

Furthermore, reports of such incidents largely focus on the victim’s behavior which “can function

as a mechanism to portray adolescent girls as women” therefore ignoring the intersection of

gender and age and thus obscuring the complex vulnerability that young girls, particularly young

girls of color and young Black girls face.

Reward Money

Unbalanced coverage and stories which include “legally irrelevant” details can greatly sway

public opinion and modify the reactions of the public to stories of violence.

33

In this sense,

communities may be increasingly desensitized to violence, less inclined to believe victims,

and/or experience apathy. Offering cash rewards,

34

a practice drawing criticism, has seen

mixed success but holds the potential to increase awareness and motivate community members

to provide information to law enforcement.

35

However, disparities exist on this front. This is once again visible in the story of Tioni Theus.

Although Theus’s body was found on January 8, it was not until January 25 and 26 that a

combined $60,000 reward was made available.

36

The award offer increased to $110,000 on

February 1 when LA City approved a $50,000 reward motion

37

; it increased to $120,000 on April

37

“City Council Approved Reward Motion,” CITY COUNCIL APPROVED REWARD MOTION | Council

District 9, February 1, 2022,

https://councildistrict9.lacity.gov/articles/city-council-approved-reward-motion.

36

Salahieh, Nouran, and Kimberly Cheng. “Tioni Theus Case: $60K Reward Available in Search for Killer

of Teen Found on Side of South L.A. Freeway.” KTLA. KTLA, January 26, 2022.

https://ktla.com/news/local-news/tioni-theus-case-60k-reward-available-in-search-for-killer-of-16-y

ear-old-found-on-side-of-south-l-a-freeway/.

35

Hallett, Emma. “Do Cash Rewards Actually Help Catch Criminals?” BBC News. BBC, June 24, 2014.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-27763842.

34

Iboshi, Kyle. “Do Cash Rewards Help Solve Crimes?” kgw.com. KGW, December 10, 2021.

https://www.kgw.com/article/news/crime/gun-violence/do-cash-rewards-solve-crimes/283-c83975

68-bc40-42e8-99cb-59ee86a25d14.

33

Schwarz, S., Baum, M.A. & Cohen, D.K. (Sex) Crime and Punishment in the #MeToo Era: How the

Public Views Rape. Polit Behav 44, 75–104 (2022).

https://doi-org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.1007/s11109-020-09610-9.

32

Fuentes, Lorena, Abha Shri Saxena and Jennifer Bitterly. "Mapping the Nexus Between Media

Reporting of Violence Against Girls: The Normalization of Violence, and the Perpetuation of

Harmful Gender Norms and Stereotypes." United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the

Empowerment of Women. September 2022.

https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/Evidence-review-Mapping-the-nexus-betwee

n-media-reporting-of-violence-against-girls-en.pdf

21

19 when LA County approved an additional $10,000.

38

In all, the reward offer totalled $120,000

after increases over a four-month period. In contrast, Brianna Kupfer was murdered on January

13 and on January 18 the West Bureau Homicide Detectives announced a $50,000 reward.

39

Community contributions quickly increased the reward offer to $250,000.

40

As of February 2023,

no progress has been made in Tioni Theus’s case while the man accused of killing Brianna

Kupfer has been located, arrested and charged.

41

Mitigation Tactics

It should be noted that in conversation with LA Civil Rights, LAPD informed LA Civil Rights that

publicizing arrests is a strategic tactic aimed at mitigating incidents of violence. However, this

tactic can have potentially unintended, damaging effects. Should news outlets not treat such

stories with care through the lens of survivor-respect and dignity, publicized stories may

perpetuate rape culture through victim-blaming, implying consent, and/or questioning victim’s

credibility. A reported analysis from the Harvard Kennedy School and University of Michigan

found that “there were 93 percent more rape reports in counties where more than 3 percent of

the coverage in a given year reflected rape culture, compared to counties where less than 3

percent of coverage reflected rape culture.”

42

In other words, in areas where news outlets used

language which perpetuated rape culture and victim blaming, sexual violence was normalized,

and thus, the number of rape reports increased.

A study from the CDC suggests that stories that focus on perpetrator consequences may be a

contributing factor in increasing the number of rapes that occur annually.

43

Additionally, the

same study suggests that media reports should be unbiased, grounded in facts, avoid

victim-blaming, and include “prevention messages in stories about sexual violence.”

44

44

Egen O, Mercer Kollar LM, Dills J, et al. "Sexual Violence in the Media: An Exploration of Traditional

Print Media Reporting in the United States, 2014–2017".

43

Egen O, Mercer Kollar LM, Dills J, et al. "Sexual Violence in the Media: An Exploration of Traditional

Print Media Reporting in the United States, 2014–2017". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.

November 27, 2020;69:1757–1761. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6947a1external

42

Ordway, Denise-Marie. “'Where There Is More Rape Culture in the Press, There Is More Rape',” The

Journalist's Resource, September 7, 2018,

https://journalistsresource.org/politics-and-government/news-coverage-rape-research/.

41

“Brianna Kupfer's Accused Killer Appears in LA Court a Day after Refusing to Show Up.” ABC7 Los

Angeles, April 22, 2022.

https://abc7.com/brianna-kupfer-accused-killer-shawn-laval-smith-appears-in-la-court/11777393/.

40

Nathan Solis, “L.A. Police Identify Suspect, Offer $250,000 Reward in Fatal Stabbing of Store

Employee,” Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles Times, January 19, 2022),

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-01-18/reward-offered-in-killing-of-brianna-kupfer-in-

hancock-park-store.

39

“West Bureau Homicide Detectives Seek the Public's Assistance in Identifying Murder Suspect

NA22003RC,” LAPD Online, January 18, 2022,

http://stglapdonline.lapdonline.org/newsroom/west-bureau-homicide-detectives-seek-the-publics-

assistance-in-identifying-murder-suspect-na22003rc/.

38

“Reward Increases to $120K in Search for Killer of Tioni Theus, Teen Found Dead on Side of 110 FWY.”

ABC7 Los Angeles, April 20, 2022. https://abc7.com/tioni-theus-reward-teen-girl/11769928/.

22

Social Media

Despite the uneven perception often perpetuated in traditional news media, it is important to

note the positive impact that social media has had in building community and solidarity amongst

survivors.

Over the course of the pandemic, victim advocates recognized and harnessed the power of

social media and smartphones to reach victims that were previously isolated.

45

The

Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Technology Review named the Jenesse Center as a

leader in this area by identifying their use of the Jenesse4Hope app to bring increased resource

access directly to individuals most in need.

Likewise, models of solidarity which began pre-pandemic can be found in recognizing the

impact of the #SayHerName campaign and media coverage of this movement.

46

Digital activism

successfully employs the media cycle and news outlets to support the survivor and/or the loved

ones of those who experience violence.

47

As scholars have previously noted, “mainstream news

media has a complicated history when it comes to covering black women, from overlooking

them completely to circulating stereotypical images of them in abundance.”

48

However, social

media provides a safe space for Black women to employ agency in telling their stories.

“#SayHerName reminds us that black, gender nonconforming women experience a complex

and layered policing from authorities that affects the way they are perceived by both journalists

and authorities as legitimate victims.”

49

This model can be applied towards understanding how

community organizations and survivor advocates utilize social media to empower Black women

and other women of color who experience violence to regain control of their story, granting them

a space to exercise autonomy, agency, and freedom which is not generally afforded to them.

Community-generated web pages such as Our Black Girls also serve as an important model for

uplifting the stories of survivors and amplifying calls for justice from the families of victims across

the nation.

50

When explaining who these women are, the Our Black Girls website states:

“These are and were our sisters, many of whom endured deception and/or violence. We

shouldn’t sweep their stories under the rug and move on to the next hot topic. We need

to remember what they went through in order to change patterns of behavior. We need

to teach our children how to protect themselves from predators who seek to do them

harm. We need to teach each other how to avoid those who whisper sweet nothings in

our ears but also use emotional or physical abuse to control us. We need to recognize

50

Marie, Erika. “Home OBG • Our Black Girls.” Our Black Girls, December 4, 2022.

https://ourblackgirls.com/.

49

Williams, Sherri. "#SayHerName: using digital activism to document violence against black women."

48

Williams, Sherri. "#SayHerName: using digital activism to document violence against black women."

47

Williams, Sherri. "#SayHerName: using digital activism to document violence against black women."

Feminist Media Studies, August 10, 2016. 16:5, 922-925, DOI: 10.1080/14680777.2016.1213574.

46

“Say Her Name.” AAPF, December 2014. https://www.aapf.org/sayhername.

45

Whitfield, Chandra Thomas. “The Pandemic Created a ‘Perfect Storm’ for Black Women at Risk of

Domestic Violence.”

23

that all that glitters isn’t gold. We need to highlight stories of our missing Black girls

because their stories go under-reported in the media — if they’re reported at all. We

cannot control the actions of those who are set in their diabolical ways, but we can learn

from one another’s experiences.”

51

As a “grassroots website that is birthed out of a heartfelt desire to make sure that these women,

who are underrepresented, aren’t forgotten,” Our Black Girls is a reminder of the importance of

grounding violence prevention and survivor support work in remembering that such incidents of

violence are experienced by real people.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

While quantitative data and trend lines are significant in demonstrating a numerical basis for

claims about disproportionate risk, these qualitative interviews (methodologically grounded in

the Collective Impact Theory of Change) yielded a wealth of information regarding services

which continually prove important in not only addressing harm and violence post-experience,

but provide opportunities for community engagement and healing which can increase the

potential for preventing violence in the first place.

52

In order to understand the scope of work that community-based organizations and external

partners provide, LA Civil Rights first considered 14 organizations, looking at the focus on their

work and communities with which they engage. Meeting requests were sent to six

organizations; three responded.

In all, LA Civil Rights held conversations with three external partners: Peace Over Violence

53

,

Women Against Gun Violence

54

, and the Jenesse Center.

55

Table 6 below details the overall

mission of each organization and the discussion focus points that were elevated during the

conversation.

(This space intentionally left blank)

55

“Jenesse Center Home Page.” Jenesse Center. Jenesse Center, Inc., 2021. https://jenesse.org/.

54

“Women against Gun Violence.” Women Against Gun Violence. Women Against Gun Violence,

February 27, 2023. https://wagv.org/.

53

“Peace over Violence.” Peace Over Violence. https://www.peaceoverviolence.org/.

52

Kania, John, and Mark Kramer. 2011. "Essentials of Social Innovation Collective Impact." Stanford

Social Innovation Review. Winter. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact.

51

Marie, Erika. “About OBG • Our Black Girls.” Our Black Girls, December 19, 2021.

https://ourblackgirls.com/about-our-black-girls/.

24

Table 6: External Engagement

Partner

Mission

Discussion Focus Points

Peace Over Violence

Building healthy relationships,

families and communities free

from sexual, domestic and

interpersonal violence.

56

● Strong policy must

accompany good

programming

● Funding challenges present

significant barriers to

programmatic efforts

● Education of law

enforcement and

engagement partners is

critical

● Long-term services and

wrap-around care present

the most effective way to

support survivors

● Prevention efforts are

crucial to mitigating future

violence

Women Against Gun

Violence

WoMen Against Gun Violence

was founded 30 years ago and,

since that time, the men and

women of WoMen Against Gun

Violence have worked tirelessly

and fearlessly to prevent gun

violence in our communities,

state, and nation through both

impactful legislation like

background checks for all gun

and ammunition sales and

through our cutting edge

programs on safe gun storage,

on voting, and on divestment.

● Training survivors on

legislative advocacy

provides opportunities to

share lived experiences

● Legislative effort to prevent

problem exacerbation is

paramount

● Partnership and building

trust with families can

prevent future violence

Jenesse Center

Jenesse’s mission is to restore

families impacted by domestic

and sexual violence through

holistic, trauma informed,

culturally responsive services,

and advance prevention

initiatives that foster and sustain

healthy, violence free

communities.

57

● Allies and engagement

partners must support in

word and deed

● Responses to survivors,

families, and advocates

must be grounded in the

promotion of dignity and

respect

57

“Who We Are.” Jenesse Center. Jenesse Center, Inc., 2021. https://jenesse.org/who-we-are/.

56

“About Us.” Peace Over Violence. https://www.peaceoverviolence.org/about-us.

25

● Wrap-around care prevents

future violence and saves

lives

● Economic security and

stability (particularly for

women head of

households) plays a key

role in violence prevention

● Partnerships with health

services have immense

potential to recognize risk

and mitigate violence

● Barriers to accessing and

utilizing funding sources

present a significant

challenge

● Programs, education, and

support must be culturally

specific

Throughout the discussions with community-based organizations, recurrent themes emerged

including:

● Need for culturally-specific and culturally-competent programming, education, and

discussion;

● Urgency of challenges in accessing and utilizing funding sources, both government

provided and philanthropic;

● Importance of prevention programming, through collaboration with health partners,

religious institutions, and youth development groups;

● Significance of survivor focused language and power in uplifting survivors narratives and

lived experiences; and

● Importance of legislative support, particularly economic and social safety nets, which can

support women and women head of households at disproportionate risk of experiencing

gender-based violence.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND NEXT STEPS:

In totality, the synthesis of background research, quantitative data, and qualitative interviews

with community based organizations results in recommendations that can be understood in four

key areas: prevention, immediate response, wrap-around service delivery, and long-term

logistics.

26

Prevention

Prior to examining potential areas of improvement and the next steps in responding directly to

survivors and their families, it is important to note the significance of prevention work. Improving

responses to survivors and their families does not mitigate the occurrence of violence in the first

place. The goal of governmental agencies and community partners should be the realization of

rendering gender-based violence support services useless. In other words, in an ideal world,

incidents of violence against women would be rare because prevention services have performed

their functions successfully.

Such prevention tactics include:

● Youth development programming and youth empowerment services;

● Family education and community safety programming; and

● Educating and partnering with healthcare providers to quickly identify individuals who may

be experiencing violence (physical, emotional, mental, and financial) and provide support

before such incidents become fatal.

All three external partners LA Civil Rights engaged with in this report provide examples of

successful prevention programming.

With regards to youth development programming and youth empowerment services, both Peace

Over Violence and the Jenesse Center engage with youth organizations to educate, empower, and

assist in the prevention of gender-based violence and violence against women.

Peace Over Violence offers a summer youth camp to encourage leadership and education about

violence prevention policy work. Likewise, Peace Over Violence assists students in organizing and

running STOP (Students Together Organizing for Peace) Clubs, where young people can become

leaders and mentors in their communities. These programs are entirely youth-led and youth-run.

Programs such as these can serve to harness restorative justice frameworks and break the school

to prison pipeline by providing students with volunteer experience and leadership training which

can support future college and career ambitions. Simultaneously, engagement with young leaders

ensures that programming is community-specific and culturally competent.

58

In this way, engaging

with these lived experiences informs the community work that Peace Over Violence conducts.

Similarly, the Jenesse Center offers youth development programs through their Raise Your Voice 4

Peace competition and Jeneration J Youth Programs.

59

These programs work to educate young

people about healthy relationships, better understand the different types of abuse, and break the

stigma around survivorship. Work such as this is integral to breaking cycles of generational trauma

and increasing conversation, which can help survivors feel safer coming forward with their story.

Family education and community safety programming plays a similar role. Although Women

Against Gun Violence focuses mainly on legislative and legal channels of advocacy, there are

59

“Raise Your Voice for Peace.” JenerationJ, n.d. https://www.jenerationj.org/.

58

Hampton, Dr. Robert, Joyce Thomas, Dr. Trisha Bent-Goodley, and Dr. Tameka Gillum Gillum. Rep. Facts

about Domestic Violence & African American Women.

27

examples of successful programming and engagement that can be examined. One such instance

is prevention programming which informs families about methods of safe gun storage as well as

builds trust with families and communities to support mediation efforts, family safety, and suicide

prevention.

Lastly, successful models of prevention can be located in engagement with healthcare providers.

The Jenesse Center has worked with local hospitals to create a curriculum which trains trauma

centers and practitioners on how to recognize domestic violence. Furthermore, the Jenesse Center

created pamphlets and flyers, such as those seen in restrooms and on the backs of medical facility

doors, and to support survivors with avenues to discreetly and safely disclose incidents of violence.

Such programmatic efforts decrease the stigma, increases the education, and works to combat the

fear of reporting repercussions.

Immediate Response

Despite such strong prevention work, the data demonstrates that violence against women,

particularly women of color and Black women remains a pervasive, life-threatening issue in the City

of Los Angeles and across the nation. Responses to calls of domestic violence incidents and

intervention in incidents of violence are high-tension and must be handled with intense dedication

to survivor-focused care.

As such, areas to improve response tactics and support include:

● Increasing training for those responding to such incidents and provide survivor-focused

education;

● Working to develop responses that do not place blame on or retraumatize the survivor;

● Locating, examining, and implementing alternatives to police response; and

● Examining the LAPD’s official policy on dual arrests during domestic violence calls as well

as the potential benefits and/or drawbacks from implementing a dual arrest policy.

As previously articulated, California is a mandatory arrest state when officers respond to domestic

violence calls. While this may serve to remove tension between two individuals in the short-term,

there are external circumstances which can retraumatize and/or harm a survivor in this process.

Peace Over Violence explained that there is a negative feedback between how the media portrays

Black women experiencing violence and how officers may interact with survivors. Additionally,

instances which result in dual arrest - when officers believe both parties to be perpetrators of

violence - may result in a retraumatizing of the survivor who acted out of self-defense. A 2008

study found that “in situations with a female offender, officers are three times more likely to make a

dual arrest.”

60

Nationally, approximately 7% of domestic violence survivors experience an incident

of dual arrest.

61

61

Hodges, Claire, Julia Kostin, William Forys, and Alexandra Mork. “From Abuse to Arrest: How America's

Legal System Harms Victims of Domestic Violence.” Brown Political Review, February 8, 2022.

https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2021/08/abuse-to-arrest/.

60

Justice Programs, and J. David Hirschel, Domestic violence cases: What research shows about arrest and

dual arrest rates § (2008).

28

Efforts to educate law enforcement and those who respond to domestic violence incidents can

ensure that such individuals understand the rights of the victim, increase the likelihood that

responders engage with compassion, respect, and dignity, and successfully connect survivors with

community services and support systems.

Above all, respect for the survivor’s wishes and efforts to avoid re-traumatizing survivors should be

the most important component of interacting with survivors and their families. Trauma-informed

work grounded in restorative justice practices can help support survivors in their healing journey.

Finally, the City should invest significant time and resources in locating, examining, and

implementing alternatives to responses to incidents of domestic violence, which may circumvent

the need for police response.

Current systems in place rely on police response to intervene and manage domestic violence

issues. However, research suggests that many survivors who called the police during a DV incident

later regretted the decision. “A 2015 survey

62

by the National Domestic Violence Hotline found that

about 75 percent of survivors who called the police on their abusers later concluded that police

involvement was unhelpful at best, and at worst made them feel less safe.”

63

Additionally, a quarter of survivors reported that they were “arrested or threatened with arrest when

reporting partner abuse or sexual assault to the police.”

64

Similarly, as highlighted earlier in this

report, survivors may not feel safe calling the police or might have secondary concerns such as

“fear of discrimination by police, invasion of privacy, wanting to protect their children, not wanting

their partner arrested, or concern that involving the authorities would exacerbate the violence.”

65

Therefore, the City can invest in exploring alternative community responses to domestic violence

that do not require calling the police. Such responses should be community-specific and

culturally-competent, grounded in the needs and wants of the local community. The City can

support such efforts through funding to community organizations already attempting to develop

these alternatives as well as investing in supporting the development of community coalitions who

can work within their networks to establish these alternatives.

Grounded in transformative justice principles, locating and implementing these alternatives can

reduce the risk of violence during a response call, decrease pressures on LAPD to respond to calls

where they may not be needed, and support communities in their efforts to care for and protect

65

Boyd-Barrett, Claudia. “Alternatives to Calling the Police for Domestic Violence Survivors.”

64

Boyd-Barrett, Claudia. “Alternatives to Calling the Police for Domestic Violence Survivors.”

63

National Domestic Violence Hotline, Who Will Help Me? Domestic Violence Survivors Speak Out About

Law Enforcement Responses. Washington, DC (2015).

http://www.thehotline.org/resources/law-enforcement-responses.

62

Boyd-Barrett, Claudia. “Alternatives to Calling the Police for Domestic Violence Survivors.” California

Health Report: Solutions for Equity. California Health Report, December 1, 2020.

https://www.calhealthreport.org/2020/12/11/alternatives-to-calling-the-police-for-domestic-violence-su

rvivors/.

29

each other. Additionally, implementing alternatives will decrease the criminalization of the

survivor.

66

However, when survivors feel that calling for police to respond to their incident is the best option,

the City should ensure that appropriate safety plans are in place to protect the victims, their loved

ones, and decrease the risk of further exacerbating violence via harm to the perpetrator.

Transformative justice principles can be utilized through practices such as mediated discussions

with all parties involved (such as families involved, the perpetrator, survivor, and involved children)

and/or accountability and reparative plans.

67

Similarly, in efforts to decrease

68

the rate of dual arrests, the City of Los Angeles should examine

the potential benefit of implementing a primary aggressor policy within LAPD.

69

The State of

California discourages dual arrests, but does not limit an officer’s ability to make such arrests.

70

Wrap-Around Service Delivery

In the aftermath of violence, survivors are often traumatized and at risk of further violence if they do