05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

RACE TO JUDGMENT: STEREOTYPING

MEDIA AND CRIMINAL DEFENDANTS*

ROBERT M. ENTMAN**

K

IMBERLY A. GROSS***

I

I

NTRODUCTION

The media’s coverage of the Duke lacrosse story generated controversy

from the very beginning. Early on, criticism came from those who felt that the

media mistreated the accuser; later, critics wondered why coverage failed to

direct more attention to the weakness of the prosecution’s case. And

throughout, critics suggested that the media mistreated the accused, rushing to

judge them, abandoning the credo of innocent until proven guilty. What

happened to these young men was indubitably a travesty of justice, and there

are important lessons to be drawn regarding how standard media routines and

practices can undermine the presumption of innocence. However, these lessons

do not support critiques that trace media derelictions to “liberal bias” or

“political correctness.”

1

Nor should coverage as a whole be characterized as

consistently slanted against the defendants. Just as it was unfair to jump to the

conclusion that the prosecutor’s emphatic insistence on the defendants’ guilt

Copyright © 2008 by Robert M. Entman and Kimberly A. Gross.

This Article is also available at http://law.duke.edu/journals/lcp.

* An earlier version of this article was presented at the symposium conference, The Court of

Public Opinion: The Practice and Ethics of Trying Cases in the Media, at Duke University School of

Law, September 28–29, 2007. The authors would like to thank Gerard Matthews and Eric Walker for

research assistance.

** J.B. & M.C. Shapiro Professor of Media and Public and International Affairs, School of Media

and Public Affairs, The George Washington University.

*** Associate Professor of Media and Public Affairs, School of Media and Public Affairs, The

George Washington University.

1. For examples of such critiques, see

generally NADER BAYDOUN & R. STEPHANIE GOOD, A

RUSH TO INJUSTICE: HOW POWER, PREJUDICE, RACISM, AND POLITICAL CORRECTNESS

OVERSHADOWED TRUTH AND JUSTICE IN THE DUKE LACROSSE RAPE CASE (2007); STUART

TAYLOR, JR. & KC JOHNSON, UNTIL PROVEN INNOCENT: POLITICAL CORRECTNESS AND THE

SHAMEFUL INJUSTICES OF THE DUKE LACROSSE RAPE CASE (2007). See also Durham-in-

Wonderland, The Times: No Harm, No Foul, http://durhamwonderland.blogspot.com/2007/04/times-

no-harm-no-foul.html (Apr. 23, 2007, 00:01 EDT), in which KC Johnson makes the following statement

that typifies many critics’ analyses: “[T]he Times’ failure in the lacrosse case . . . was attributable to

reporters and editors allowing their worldviews to distort the facts.” As far as we can tell there is no

published book or article that engages in systematic content analysis of media coverage over the entire

period of the case. A number of sources provide qualitative analysis of selected media coverage. See,

e.g., T

AYLOR & JOHNSON, supra (focusing mainly on coverage that suggests a bias against the

defendants); David J. Leonard, Innocent Until Proven Innocent, 31 J. S

PORT & SOC. ISSUES 25 (2007)

(reaching a different conclusion by focusing on efforts to exonerate and defend the students).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

94 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

meant they were guilty, so it is wrong to assess the media by relying on

unsystematic impressions and inevitably flawed memories filtered through

stereotypes of, and generalized dissatisfaction with, U.S. journalism.

To draw the proper lessons from this incident, its coverage is best examined

in the larger context of research on media, race, and crime. Thus, this article

begins by reviewing the extensive literature in the subfield, highlighting the

ways crime news typically reinforces stereotypes of blacks and other nonwhites,

particularly Latinos, and contributes to more-generalized racial antagonism.

Understood in this context, news of the Duke lacrosse case diverges markedly

from typical crime coverage. This is worth bearing in mind when recalling the

amount of attention devoted to the injustices suffered by the Duke students

2

relative to the attention given to potential injustices suffered by more-typical

defendants.

This article systematically analyzes coverage of the Duke lacrosse case over

the year that it received attention in the news. It distinguishes between news

reporting and news commentary and between national and local coverage. In

analyzing the reporting, it also distinguishes between two phases. The first

phase, between March 14 and April 10, 2006, was before the first exonerating

DNA evidence became available. The post-DNA period, from April 10, 2006,

through April 11, 2007, the date on which the prosecutor announced that all

charges were being dropped, constitutes the second phase. The initial DNA

information could have clearly marked the unraveling of the case, serving as a

signal to reporters to dig deeper, but the weakness of the prosecutor’s case was

not fully reflected in much of media treatment until well into the post-DNA

phase. That is not the whole story, however. The data reveal a more

complicated pattern of news coverage that neither continually violated, nor

perfectly conformed to, journalistic ideals. News of this case is explained using

theories of news slant that emphasize how the skill and incentives of players in a

two-sided framing contest—here, criminal defense versus law-enforcement

agencies—interact with the incentives, norms, and limitations of the news

media. These theories take the analysis far beyond any simplistic, monocausal

explanation of media shortcomings in this single instance and toward an

understanding of the more general problems posed by normal media behavior

for the impartial administration of justice in the United States.

II

J

OURNALISTIC ROUTINES, PRETRIAL

P

UBLICITY, AND THE DUKE LACROSSE CASE

Many of the traits on exhibit in the Duke lacrosse case characterize not only

crime news, but news of the policy process generally. These include

2. See, e.g., BAYDOUN, supra note 1; TAYLOR & JOHNSON, supra note 1; DON YEAGER & MIKE

PRESSLER, IT’S NOT ABOUT THE TRUTH: THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE DUKE LACROSSE CASE AND

THE

LIVES IT SHATTERED (2007).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 95

overreliance on public officials, overuse of standardized story scripts and

familiar stereotypes, and “pack journalism”—the tendency of reporters from

nominally competitive news organizations to converge on the same framings. In

the case of crime coverage, these media routines can facilitate a pro-prosecution

slant that appears across news coverage when law-enforcement officials are

eager to promote claims of guilt. Perhaps the most important prerequisite to

achieving the journalistic ideal of balance is the requirement of having reliable,

legitimate, and credible sources competing to advance alternative narratives.

Without such contending elite forces working to impose different frames on the

coverage of an issue, media coverage is usually one-sided and arguably unfair to

at least some participants.

3

News of criminal cases often does not meet the

requirement of contending elites working to uphold alternative narratives.

4

Thus, crime news is almost always heavily slanted toward the prosecution for a

structural reason: unlike in coverage of policy debates over, say, social security,

abortion, or the environment, there is no institutionalized political-party system

to provide a more-or-less automatic two-sided debate among credible elites that

journalists can reflect in their coverage.

Pretrial journalism, in particular, tends generally to treat the presumption of

innocence as a formality, largely limited to using the word allege, without

actually covering the story in a balanced fashion that makes clear the possibility

that district attorneys (D.A.s), police, and judges (and juries) can make

mistakes or have bureaucratic, psychological, or political motives.

5

Although relatively few crimes receive sustained media attention,

6

when

they do, coverage is likely to include information that can be considered

prejudicial under American Bar Association (ABA) guidelines. In covering

crime stories, journalists typically rely on law-enforcement officials’ views,

downplaying the defense perspective while minimally acknowledging the

3. W. LANCE BENNETT ET AL., WHEN THE PRESS FAILS: POLITICAL POWER AND THE NEWS

MEDIA FROM IRAQ TO KATRINA (2007) (examining the implications of news framing on, inter alia, the

Abu Ghraib incidents); R

OBERT M. ENTMAN, PROJECTIONS OF POWER: FRAMING NEWS, PUBLIC

OPINION, AND U.S. FOREIGN POLICY (2004) (examining the implications of news framing on public

opinion in media coverage of U.S. foreign policy) [hereinafter P

ROJECTIONS]; Robert M. Entman,

Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power, 57 J. C

OMM. 163, 164–70 (2007) [hereinafter Framing

Bias] (discussing the way in which framing and biases in media coverage interact in the creation of news

slant); Robert M. Entman et al., Doomed to Repeat: Iraq War News, 2003-2007, 52 A

M. BEHAV.

SCIENTIST (Dec. 2008) (suggesting that a key factor facilitating the one-sided framing of U.S. foreign

policy is the fact that “the magnitude and cultural resonance of media attention to negative results of

foreign policy tends to go down as they become more commonplace” (emphasis in original)).

4. See P

ROJECTIONS, supra note 3, at 151.

5. This was certainly an issue in the Duke lacrosse case, when the prosecutor’s potential ulterior

motives were perhaps more obvious than normal. Although journalists paid some attention to the

connection between the case and District Attorney Michael Nifong’s upcoming election campaign, in

hindsight it seems they gave his claims undue deference, perhaps because it seemed literally incredible

that a D.A. in the national-media glare would engage in blatant misconduct.

6. Ralph Frasca, Estimating the Occurrence of Trials Prejudiced by Press Coverage, 72

J

UDICATURE 162, 165 (1988).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

96 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

innocence presumption.

7

Thus, news of crime generally exhibits a pro-

prosecution bias, rooted most importantly in this dependence of reporters on

official and, therefore, purportedly credible sources.

8

One study measuring the

extent of pretrial publicity on Los Angeles television news found that nineteen

percent of the defendants in crime stories were associated with at least one

category of potentially prejudicial information as defined by the ABA.

9

Another study found that twenty-seven percent of suspects in crime stories

were described using prejudicial information.

10

Most of this information was

cited to law-enforcement officers and prosecutors.

11

The imbalanced perspective in the news, facilitated by overreliance on

public officials, is compounded by the inability of criminal-defense teams, even

well-funded ones, to counter the public-relations machinery of law-enforcement

agencies. The latter’s spokespersons enjoy established relationships with local

and wire-service reporters, and they serve superiors with strong career

incentives to maximize publicity for crime-fighting successes.

12

Beyond this, few

reporters—especially those from national news organizations parachuting into a

local scene like Durham—have the time to investigate documentary evidence,

to interview ordinary citizens, or to otherwise probe alternative sources of

information. Defendants face further jeopardy from the very facts that a district

attorney has indicted and police officers have arrested them. For most people,

these actions connote guilt because they believe (based perhaps in part on

television crime shows like Law and Order and CSI) that officials take these

7. See Michael Welch, Melissa Fenwick & Meredith Roberts, Primary Definitions of Crime and

Moral Panic: A Content Analysis of Experts’ Quotes in Feature Newspaper Articles on Crime, 34 J.

RES.

CRIME & DELINQ. 474, 474, 488 (1997) (demonstrating a general tendency in newspaper crime

coverage to rely on law-enforcement officials and to underrepresent the perspectives of defense

lawyers).

8. See id. The defense attorneys, the contending side, are likely viewed as more biased than

prosecutors—their job is to try to get their clients off—and thus their claims are likely to be viewed

more skeptically.

9. Travis L. Dixon & Daniel Linz, Television News, Prejudicial Pretrial Publicity, and the

Depiction of Race, 46 J. B

ROADCASTING & ELECTRONIC MEDIA 112, 127–29 (2002) (reporting

findings based on a sample that yielded two seven-day composite weeks of news programming with 200

programs in all).

10. Dorothy J. Imrich et al., Measuring the Extent of Prejudicial Pretrial Publicity in Major

American Newspapers: A Content Analysis, 45 J. C

OMM. 94, 94 (1995).

11. Id.; see also Celeste Michelle Condit & J. Ann Seltzer, The Rhetoric of Objectivity in the

Newspaper Coverage of a Murder Trial, 2 C

RITICAL STUD. MASS COMM. 197, 197 (1985) (showing

subtle pro-prosecution bias in newspaper reporting on a criminal trial); Nancy Mehrkens Steblay et al.,

The Effects of Pretrial Publicity on Juror Verdicts: A Meta-Analytic Review, 23 L

AW & HUM. BEHAV.

219, 219 (1999) (suggesting that negative pretrial publicity typically and significantly promotes guilty

judgments); Christina A. Studebaker & Steven D. Penrod, Pretrial Publicity: The Media, the Law, and

Common Sense, 3 P

SYCHOL. PUB. POL’Y & L. 428 passim (1997) (using the term “pretrial publicity” as

synonymous with prejudicial pretrial publicity, suggesting that legal scholars and many lawyers presume

as a matter of course that publicity will negatively slant against defendants).

12. See Edward Stringham, Justice After Nifong, W

ASH. TIMES, May 22, 2007, at A15 (“[T]he

incentives created by our highly politicized legal system . . . reward[] law enforcement officials for high

conviction rates, rather than meting out justice. Indeed, in high-profile cases, law enforcement officials

frequently use a conviction to advance their career.”).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 97

actions only after amassing strong evidence.

13

Journalists no less than their

audiences can fall prey to these not unreasonable assumptions.

III

R

ESEARCH ON BLACKS, WHITES, CRIME, AND NEWS

This section sets a context for evaluating coverage of the Duke lacrosse case

by considering the normal in crime news: a largely unintentional slant that

reinforces whites’ antagonism, particularly toward black defendants, and more

generally equates blacks with crime and danger. As this section shows, virtually

all serious academic research reveals a consistent bias against African

Americans, both in the coverage of crime and more generally.

14

At the same

time, media content—not just news but entertainment and “infotainment”—

usually promotes white privilege and the idea that whites occupy the top of a

racial hierarchy wherein blacks are largely and naturally relegated to the

bottom.

15

Thus the Duke lacrosse case is the exception that proves the rule, an

inversion of the normal situation in which black defendants in criminal cases are

especially likely to be presumed guilty because they are subject to the

stereotypes or heuristics that most whites apply to the category “black

person.”

16

A. The Racial Nature of Crime Coverage

Media stereotypes consist of recurring messages that associate persons of

color with traits, behaviors, and values generally considered undesirable,

inferior, or dangerous. In the context of crime coverage, there is considerable

evidence that media portray blacks and Latinos as criminal and violent.

17

These

images matter because they are a central component in a circular process by

which racial and ethnic misunderstanding and antagonism are reproduced, and

13. See, e.g., RONALD WEITZER & STEVEN A. TUCH, RACE AND POLICING IN AMERICA:

CONFLICT AND REFORM 41 (2006) (reporting that 86% of whites, 73% of African Americans, and 80%

of Latinos were either “Very” or “Somewhat Satisfied” with the police department in their city and

very few were “Very Dissatisfied”); Lawrence D. Bobo & Victor Thompson, Unfair by Design: The

War on Drugs, Race, and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System, 73 S

OC. RES. 445, 454-62

(showing that whites’ perceptions of the fairness of the criminal-justice system exceeds blacks’

perceptions on multiple measures).

14. On media and race generally, see R

OBERT M. ENTMAN & ANDREW ROJECKI, THE BLACK

IMAGE IN THE WHITE MIND: MEDIA AND RACE IN AMERICA (2000).

15. See generally R

OBERT ENTMAN, YOUNG MEN OF COLOR IN THE MEDIA: IMAGES AND

IMPACTS, JOINT CENTER FOR POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC STUDIES BACKGROUND PAPER (2006).

16. See generally Patricia G. Devine, Stereotypes and Prejudice: Their Automatic and Controlled

Components, 56 J.

PERSONALITY & SOC. PSYCHOL. 5, 5 (1989) (demonstrating that both “high- and

low-prejudiced persons are . . . knowledgeable of the cultural stereotype [of blacks]. . . . [This]

stereotype is automatically activated . . . [and] low-prejudice responses require controlled inhibition of

[this] automatically activated stereotype.”). Thus, when individuals are not consciously monitoring their

stereotypes, both the prejudiced and the unprejudiced produce stereotype-consistent evaluations. See

id. Blacks are often stereotyped as lazy and violent, contributing further to presumptions of criminal

tendencies. P

AUL M. SNIDERMAN & THOMAS PIAZZA, THE SCAR OF RACE 38–46 (1993).

17. See infra notes 18–39 and accompanying text.

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

98 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

thus become predictable influences in the criminal-justice process. Such

coverage may reinforce biases against black and Latino defendants even in the

absence of specific pretrial publicity about a given defendant’s case. Here are

some examples from the extensive research literature detailing the varied and

subtle ways in which television and print news stereotype blacks and Latinos in

crime coverage:

1. Blacks and Latinos are more likely than whites to appear as lawbreakers

in news—particularly when the news is focusing on violent crime.

18

Blacks and Latinos are more likely to appear as perpetrators than

victims.

19

Blacks are overrepresented as perpetrators of violent crime

when news coverage is compared with arrest rates.

20

Work that engages

in “inter-reality” comparisons suggests the media portrayal is somewhat

less distorted than the comparison of the number of black, white, and

18. For examples of studies reaching this conclusion through “intergroup comparisons” (that is,

comparing the extent to which members of different racial groups are portrayed as perpetrators) based

on evidence from systematic content analyses, see Travis L. Dixon & Daniel Linz, Overrepresentation

and Underrepresentation of African Americans and Latinos as Lawbreakers on Television News, 50 J.

C

OMM., Spring 2000 at 131, 149 (local television news programming in Los Angeles and Orange

counties, Cal.); E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 14 (multiple media formats and locations); Daniel

Romer et al., The Treatment of Persons of Color in Local Television News: Ethnic Blame Discourse or

Realistic Group Conflict?, 25 C

OMM. RES. 286, 294–98 (1998) (local television news programming in

Phila., Pa.). See also Travis L. Dixon & Cristina L. Azocar, The Representation of Juvenile Offenders by

Race on Los Angeles Area Television News, 17 H

OW. J. COMM. 143, 143, 151 (2006) (portrayal of

juvenile lawbreakers in local television news programming in L.A., Cal.).

19. For examples of studies employing “inter-role comparisons” (that is, comparing the extent to

which members of a specific racial or ethnic group are portrayed in more- and less-sympathetic roles)

to find that people of color are more likely to be portrayed as criminals than as victims, see Travis L.

Dixon & Daniel Linz, Race and the Misrepresentation of Victimization on Local Television News, 27

C

OMM. RES. 547, at 559–560 (2000); Romer et al., supra note 18, at 294–98, (finding also that blacks are

more likely to be portrayed as perpetrators than as bystanders, experts, or other nonperpetrators).

20. For examples of studies reaching this conclusion through “inter-reality comparisons” (that is,

comparing media portrayals with “reality” by comparing content analyses to arrest statistics), see

Dixon & Linz, supra note 18, at 131 (finding blacks, though not Latinos, overrepresented as

lawbreakers); Franklin D. Gilliam, Jr. et al., Crime in Black and White: The Violent, Scary World of

Local News, 1 H

ARV. INT’L. J. PRESS/POL., June 1, 1996, at 6, 10–12 (finding blacks, though not

Latinos, overrepresented as lawbreakers in coverage of violent and nonviolent crimes). See also Dixon

& Azocar, supra note 18, at 143, 152–53 (portraying juvenile lawbreakers). But see Franklin D. Gilliam,

Jr. & Shanto Iyengar, Prime Suspects: The Influence of Local Television News on the Viewing Public, 44

A

M J. POL. SCI. 560, 562 (2000) (finding that blacks appear in crime coverage at rates not much

different than the actual black arrest rate for Los Angeles County, Cal.); Ted Chiricos & Sarah

Eschholz, The Racial and Ethnic Typification of Crime and the Criminal Typification of Race and

Ethnicity in Local Television News, 39 J. R

ES. CRIME & DELINQ. 400, 400 (2002) (finding blacks

underrepresented when comparing the racial composition of television news suspects on Orlando, Fla.

TV news with the percentages of arrests involving blacks and whites). Of course, in this context, the

heavy emphasis on violent crime in television news coverage becomes especially troubling. See

generally L

ORI DORFMAN & VINCENT SCHIRALDI, OFF BALANCE: YOUTH, RACE, AND CRIME IN THE

NEWS (2001) (surveying the representation of crime in the news media in connection with youth and

race). There is no natural law that makes street crime and violence automatically more newsworthy

than city-budget debates, or education, mass transit, and other policy discussions to which local TV

news typically pays comparatively little attention. Summarizing the results of these content analyses is

somewhat complicated by different standards of comparison (for example, comparing the extent to

which members of different racial groups are portrayed as perpetrators versus comparing the media

portrayal with “reality” through the use of measures such as arrest statistics). See, e.g., Dixon & Linz,

supra note 18, at 131 (employing intergroup and inter-reality comparisons).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 99

Latino perpetrators might imply.

21

Nonetheless, the picture is troubling,

suggesting that news cultivates the perception of blacks and Latinos as

lawbreakers.

2. In contrast, whites are overrepresented as victims of violence and as

law-enforcers, while blacks are underrepresented in these sympathetic

roles.

22

3. These patterns are more disturbing when one considers that blacks and

Latinos may not appear as frequently as whites outside the crime-news

context. Because of the values that define the newsworthy, blacks in

criminal roles tend to outnumber blacks in socially positive roles in

newscasts and daily newspapers.

23

In some areas, at least, Latinos may

receive even worse treatment than blacks. Chiricos and Eschholz

examined three weeks of local-news programming in Orlando and found

that one in twenty whites appearing on the local television news was a

criminal suspect compared with one in eight blacks and one in four

Latinos.

24

4. Studies of local news in Chicago and elsewhere suggest that depictions

of black suspects (mostly young men) tend to be more symbolically

21. Measures of reality to which representations are compared are deeply problematic. Assume

blacks and Latinos are represented in proportion to their actual crime rates according to some

relatively simple measures (for example, blacks commit 25% of crimes in a metropolitan area and

constitute 25% of accused criminals in local news reports). This leaves aside many ambiguities in the

guidelines offered by proportionality as a standard: for example, does accuracy demand that today’s

coverage offer racial proportionality in terms of last week’s racial crime rate, or this year’s, or last

year’s, or should it reflect rate of change in relative racial crime rates? If blacks committed 35% of

armed robberies last month, what happens if they commit 12% this month, which one finds out only

when the statistics are compiled at some later date? Should one underreport the following month’s

black-committed armed robberies to make up for the previous month’s overrepresentation? Exactly

how should coverage be calibrated to severity of crime committed by members of racial groups—by

devoting more time, more-vivid language, more details on the victims? And how does one measure

“severity” anyway? For further discussion, see E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18 at 213–15. The list

could go on. More importantly, even if blacks and Latinos are somehow represented in “proper”

proportion, a lack of contextual reporting reinforces whites’ ignorance and tendencies to stereotype. As

an example of needed context, black crime rates among young adult males are no different from white

rates when controlling for employment status. In other words, unemployment is a primary cause of

black crime, unemployment rooted in discrimination, poor education systems, and other structural

causes. See W

ILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, WHEN WORK DISAPPEARS: THE WORLD OF THE NEW URBAN

POOR 22 (1996).

22. Travis L. Dixon et al., The Portrayal of Race and Crime on Television Network News, 47 J.

BROADCASTING & ELECTRONIC MEDIA 498, 498 (2003); see also Chiricos & Eschholz, supra note 20,

at 20 (finding “[b]lacks . . . more likely to appear as criminal suspects than as victims or positive role

models”); Dixon & Linz, supra note 18, at 131 (finding whites overrepresented as law defenders on

local news programming in L.A., Cal., though blacks are neither over- nor underrepresented compared

to county employment rates); Dixon & Linz, supra note 19, at 564 (finding, via intergroup comparisons,

whites more likely than blacks or Latinos to be portrayed as victims of crime, and whites

overrepresented as homicide victims on local television news); Romer et al., supra note 18, at 286

(finding “Whites overrepresented as victims of violence compared to their roles as perpetrators, and

persons of color . . . overrepresented as perpetrators of violence against White[s]”).

23. See E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18, at 86.

24. Chiricos & Eschholz, supra note 20, at 407, 416. Though this same study did not find that blacks

were overrepresented when looking only among TV-news suspects, id. at 410, this lack of other

positive-role portrayals for blacks reinforces the link between blacks and crime.

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

100 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

threatening than those of whites accused of similar crimes.

25

Black

defendants in one study were more likely to be shown in mug shots.

26

In

the ubiquitous “perp walks,” blacks were twice as likely as whites to be

shown under some form of physical restraint by police—although all

were accused of scary and generally violent crimes.

27

In some notorious,

highly publicized crimes—such as the 1989 alleged rape of a wealthy,

young white woman in Central Park by a “gang” of Latino and black

young men—young men of color appear particularly susceptible to

portrayals that associate them with extreme threat and less-than-human

traits. Narratives routinely used such words as “savage” and “wild.”

28

5. Violence and youth, especially male youth, are closely linked: most

stories that feature young people on local news depict violence they

commit or suffer, and in those stories, older white men are the dominant

speakers.

29

Local news does not often portray young persons as

positively contributing to society.

30

6. People of color are more likely to be subjected to negative pretrial

publicity. One study found that black and Latino defendants are twice as

likely as white defendants to be subjected to negative pretrial publicity

and that defendants who victimized whites were more likely to have

prejudicial information broadcast about them than defendants who

victimized nonwhites.

31

25. See, e.g., ENTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18, at 78–93 (reporting and discussing the results of a

study on the use of racial stereotypes in local-crime news coverage in Chicago, Ill.); Chiricos &

Eschholz, supra note 20, at 20 (finding that blacks, and especially Latinos, who appeared as suspects in

Orlando, Fla., local-crime news coverage appeared in more threatening contexts than whites).

26. E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18, at 82.

27. Id. at 83–84. One complexity to note is that it may well be true that police officers physically

restrain more black defendants than they restrain white defendants because of the officers’ own racial

fears. News reports that may cultivate negative stereotyping and fear of young men of color may also

accurately convey aspects of the “real world.” This consideration indicates that solving the problem

may require more than simply urging journalists to report on discrete events or specific facts more

accurately.

28. See generally Michael Welch et al., Moral Panic Over Youth Violence: Wilding and the

Manufacture of Menace in the Media, 34 Y

OUTH & SOC’Y 3 (2002) (discussing use of the term “wilding”

and synonyms for “wild” in media coverage following this incident). Later evidence showed that the

idea of a gang of nonwhites repeatedly assaulting the woman was exaggerated and most of the accused

were exonerated. See Jim Dwyer, New Slant on Jogger Case Lacks Official Certainty, N.Y.

TIMES, Jan.

28, 2003, at B7; Susan Saulny, Convictions and Charges Voided In ‘89 Central Park Jogger Attack, N.Y.

TIMES, Dec. 20, 2002, at A1.

29. Lori Dorfman & Katie Woodruff, The Roles of Speakers in Local Television News Stories on

Youth and Violence, 26 J.

POPULAR FILM & TELEVISION 80, 81, 83 (1998).

30. See id.; D

ORFMAN & SCHIRALDI, supra note 20. This coverage leads to specific perceptions of

juvenile offenders. See Robert K. Goidel et al., The Impact of Television Viewing on Perceptions of

Juvenile Crime, 50 J.

BROADCASTING & ELECTRONIC MEDIA 119, 134 (2006) (reporting the results of

a survey of Louisiana residents that found viewers of television news were more likely to believe

juvenile crime was increasing, more likely to overestimate the percentage of juvenile offenders

imprisoned for violent crimes, and more likely to believe rehabilitation in prison was more effective

than community-based rehabilitation programs).

31. Dixon & Linz, supra note 9, at 128–29 (finding also that, accounting for the race of the victim,

being black with a white victim more than doubles the odds of prejudicial pretrial information

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 101

7. Several studies show that black victims are less likely to be covered than

white victims in newspaper coverage of crime.

32

But unlike studies

focused on local television, studies of newspapers do not indicate that

minorities are overrepresented as perpetrators.

33

Newspaper coverage is

somewhat better than local television news on some dimensions, if only

because it does not follow the “if it bleeds it leads” norm and devotes

much less of its news space to crime.

34

Stories themselves are often

longer and, on average, perhaps more likely to contain more context

than TV. On the other hand, the additional words devoted to crime by

newspapers might yield a greater net volume of negative pretrial

information.

35

8. Aside from crime, perhaps the most frequent and disproportionate

association made with persons of color in the news media is poverty. In

stories featuring poverty as a topic, newsmagazines like Time and

Newsweek overrepresent blacks, while underrepresenting whites,

Latinos, and Asians.

36

At the same time, the magazines overrepresent

appearing; a Latino with a white victim more than triples the odds that prejudicial information will be

aired when compared with a white defendant and white victim).

32. See, e.g., John W.C. Johnstone et al., Homicide Reporting in Chicago Dailies, 71 J

OURNALISM

Q. 860, 860 (1994) (homicide coverage in Chicago, Ill., newspapers); David Pritchard & Karen D.

Hughes, Patterns of Deviance in Crime News, 47 J. C

OMM., Summer 1997, at 49, 49 (homicide coverage

in Milwaukee, Wis., newspapers); Susan B. Sorenson et al., News Media Coverage and the

Epidemiology of Homicide, 88 A

M. J. PUB. HEALTH 1510, 1510 (1998) (comparing a special, seven-part

series on homicide in the Los Angeles Times to the homicides that occurred during the period featured

in the report and finding that homicides of blacks and Latinos were substantially underreported);

Alexander Weiss & Steven Chermak, The News Value of African-American Victims: An Examination

of the Media’s Presentation of Homicide, 21 J. C

RIME & JUST. 71, 71 (1998) (homicide coverage in

Indianapolis, Ind., newspapers).

33. See, e.g., David Pritchard, Race, Homicide, and Newspapers, 62 J

OURNALISM Q. 500, 500

(1985) (finding homicides with minority suspects get less coverage in Milwaukee newspapers); Shelly

Rogers et al., ‘Reality’ in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 21 N

EWSPAPER RES. J., Summer 2000, at 51, 63 (

“African Americans did not dominate the stereotyped role[] of perpetrator” in St. Louis, Mo.,

newspaper coverage.); Susan Sorenson et al., supra note 32, at 1511 (finding suspect characteristics like

race unrelated to coverage in the Los Angeles Times with one exception of interest here: “Latino

suspects were less likely than others to receive coverage . . . .”). But see Weiss & Chermak, supra note

32, at 78 (finding that, although the number of articles in coverage of murder in Indianapolis

newspapers was similar whether the suspect was black or white, the average length of the article was

longer if the suspect was black); Tara-Nicholle Beasley Delouth & Cindy J.P. Woods, Biases Against

Minorities in Newspaper Reports of Crime, 79 P

SYCHOL. REP. 545 (1996) (finding some evidence, with

admittedly small numbers necessitating caution about the conclusions, that disclosure of the victims’

identity was more common when the suspect was an ethnic minority).

34. Newspapers emphasize violence less in their news than television. See E

NTMAN & ROJECKI,

supra note 18, at 88–90 (comparing newspaper and local television-news coverage); Joseph F. Sheley &

Cindy D. Ashkins, Crime, Crime News, and Crime Views, 45 P

UB. OPINION Q. 492, 492 (1981)

(comparing newspaper and television-news coverage with police figures). Crime is the dominant topic

on local television news and an important topic in metropolitan daily papers. See R

ICK EDMONDS &

THE PROJECT FOR EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM, THE STATE OF THE NEWS MEDIA 2006,

http://www.stateofthenewsmedia.com/2006/narrative_newspapers_contentanalysis.asp?cat=2&media=3

(reporting results of a content analysis of news coverage by local and national television news and

newspapers on May 11–12, 2006).

35. Dixon & Linz, supra note 9, at 130–31.

36. See Rosalee Clawson & Rakuya Trice, Poverty as We Know It: Media Portrayals of the Poor, 64

P

UB. OPINION Q. 53, 56–57 (2000) (analyzing media depictions of poverty demographics).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

102 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

the nonworking poor and the urban poor in their illustrations of

poverty.

37

In this way, not only do media encode poverty as an especially

black trait, but they undermine potential sympathy, especially among

the white majority, for antipoverty programs.

38

Poverty can be portrayed

as a condition that merits sympathy, but it more often appears

associated with threats in the form of crime, violence, drugs, gangs, and

aimless activity.

39

Such messages not only stereotype the blacks and Latinos who are featured

in them, but also contribute to a stereotypical association between blacks,

criminality, and guilt that can influence evaluations and behavior. These

messages also reinforce negative emotions and a sense of social distance that

may promote a belief in inherent group conflict between blacks or Latinos and

whites. Moreover, these stereotypes arise not merely from the news, but from

TV and film entertainment, advertising, and sports programming as well.

40

The implications of this research for public attitudes are troubling. Messages

continually associating people of color, especially blacks, with poverty and

crime reinforce the updated form of racial prejudice known as symbolic racism,

racial resentment, or racial animosity.

41

In the absence of contextual information

about discrimination and other forces that produce the poverty, racialized

images of poverty reinforce the stereotype that blacks are lazy and therefore

deserve their impecuniousness. Racialized crime coverage reinforces the

37. See id. at 60.

38. See generally E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18, at 103–06 (discussing the implications of

news-media portrayals of race and poverty on, inter alia, racial animosity); M

ARTIN GILENS, WHY

AMERICANS HATE WELFARE: RACE, MEDIA, AND THE POLITICS OF ANTIPOVERTY POLICY, (1999)

(examining media portrayals of and attitudes toward race, poverty, and welfare); Robert M. Entman,

Television, Democratic Theory, and the Visual Construction of Poverty, in 7 R

ESEARCH IN POLITICAL

S

OCIOLOGY 139 (Philo C. Washburn ed., 1995) (discussing the effects of race and poverty in news

media on the nonpoor’s support for antipoverty policy); Martin Gilens, “Race Coding” and White

Opposition to Welfare, 90 A

M. POL. SCI. REV. 593 (1996) (“[R]acial attitudes are the single most

important influence on whites’ welfare views.”).

39. See E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18, at 96–100 (reporting results of a study of the depiction

of poverty in local newspapers and local and national television news).

40. See R

OBERT M. ENTMAN, YOUNG MEN OF COLOR IN THE MEDIA: IMAGES AND IMPACTS,

15–17 (2006) (discussing the prevalence and implications of racial stereotyping in these contexts). Such

media routines are central to a self-perpetuating cycle that reproduces white racial antagonism directed

at persons of color. The cultural reproduction of racial antagonism among whites as a result of media

coverage reinforces discrimination, which promotes joblessness and hopelessness among African

Americans, and that in turn encourages criminal behavior. This cycle yields continuing crime news that

reinforces the stereotypes and the automatic and unconscious anxieties and associations of blacks with

danger and lawlessness. Figure 1 in Entman offers a graphic representation of this circular process,

which in admittedly oversimplified and abstract form depicts the complex interrelationships among

white elites and the institutions that they dominate; ordinary white citizens’ sentiments, decisions, and

behaviors; and the lives and life chances of persons of color. Id. at 9. See generally E

NTMAN &

ROJECKI, supra note 18.

41. See generally E

NTMAN & ROJECKI, supra note 18 (discussing the interactions of portrayals of

race in media, racial animosity, and symbolic racism); D

ONALD R. KINDER & LYNN M. SANDERS,

DIVIDED BY COLOR: RACIAL POLITICS AND DEMOCRATIC IDEALS (1996) (discussing racial

resentment in the context of U.S. politics); Christopher Tarman & David O. Sears, The

Conceptualization and Measurement of Symbolic Racism, 67 J. P

OL. 731 (2005) (studying and discussing

the effects of symbolic racism on racial policy preferences).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 103

stereotype that blacks are not just lazy, but violent.

42

Both of these stereotypes

are important components of this new form of racial prejudice. Moreover,

empirical evidence demonstrates associations between racial resentment and

whites’ support of punitive crime policies

43

and opposition to preventative

policies.

44

B. Effects on White Attitudes

The effects on whites of this heavy representation of blacks and Latinos in

crime news have been documented through empirical studies. As Gilliam and

Iyengar argue, coverage of this nature creates a “crime script” in which crime is

violent and perpetrators are black. Repeated exposure to this script promotes

and reinforces negative racial stereotypes.

45

Kang uses the metaphor of the

“Trojan Horse Virus” to describe how local television news of this nature can,

without viewers’ awareness and without intent on the part of news producers,

create and reinforce associations between blacks and violence in the minds of

citizens.

46

These stereotype-based cognitive and emotional responses are often

automatically, quickly, and unconsciously triggered, and go on to affect a wide

range of sentiments.

47

For example, one researcher found that an act (an

ambiguous shove) was interpreted as more violent when performed by a black

than when performed by a white,

48

consistent with the notion that “black” and

“violent” have become linked in the minds of many individuals. Other work

illustrates that when presented with an ambiguous suspect, individuals are more

likely to assume the suspect is black.

49

Further evidence comes from studies

42. See the 2000 General Social Survey. Individuals were asked to rate blacks, Asians, Latinos, and

whites as a group on two traits of relevance here: on a seven-point scale from lazy to hardworking and

on a seven-point scale from violence-prone to not-violence-prone. Thirty-five percent of respondents

rated blacks as lazy (that is, they gave blacks a rating corresponding to the three numbers at the

negative end of the scale for lazy), 21% rated Latinos as lazy, and only 11% rated whites or Asians as

lazy. The stereotypes are more extreme in the case of violence: 48% rated blacks as prone to violence

(that is, they gave blacks a rating that corresponded to the three numbers at the negative end of the

seven-point scale), 38% rated Latinos as prone to violence, 21% rated whites as prone to violence, and

17% rated Asians as prone to violence.

43. See Gilliam & Iyengar, supra note 20, at 560, 571 (“[E]xposure to the racial element of the

[experiment’s] crime script increases [whites’] support for punitive approaches to crime . . . .”).

44. Eva G.T. Green et al., Symbolic Racism and Whites’ Attitudes Towards Punitive and

Preventative Crime Policies, 30 L

AW & HUM. BEHAV. 435, 435 (2006).

45. See Gilliam & Iyengar, supra note 20, at 560–61.

46. See Jerry Kang, Trojan Horses of Race, 118 H

ARV. L. REV. 1489, 1553–54, 1562–63 (2005).

Kang draws on psychological work on implicit attitudes, id. at 1506–14 (citing, for example, Brian A.

Nosek, Mahzarin Banaji & Anthony G. Greenwald, Harvesting Implicit Group Attitudes and Beliefs

from a Demonstration Web Site, 6 G

ROUP DYNAMICS 101, 105 (2002)), in describing how coverage may

be detrimental. Implicit-attitudes research shows that whites express some explicit preference for their

own group but much greater levels of implicit preference. Id. at 1513. Even individuals who honestly

self-report positive attitudes toward individuals in other racial categories may hold implicit negative

attitudes toward that group. Id.

47. Id. at 1515–48.

48. B.L. Duncan, Differential Social Perception and Attribution of Intergroup Violence: Testing the

Lower Limits of Stereotyping of Blacks, 34 J. P

ERSONALITY & SOC. PSYCHOL. 590, 590 (1976).

49. See Gilliam & Iyengar, supra note 20, at 564 (finding that subjects who viewed a crime story

with no mug shot were much more likely to misremember seeing a black perpetrator, consistent with

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

104 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

using a computerized experiment in which participants were instructed to shoot

an armed target but not an unarmed target.

50

The target individual was either

black or white, was holding either a gun or another object, and was presented in

a realistic background.

51

Under time pressure, participants were more likely to

mistakenly shoot an unarmed black target than an unarmed white target and

were more likely to mistakenly fail to shoot an armed white target than an

armed black target.

52

In other words, participants in the study were more likely

to assume wrongly that a black individual was armed and assume wrongly that a

white individual was not.

53

Other research reveals the interaction between these

experimental results and media images.

54

This work suggests that the shooting

bias results from the mental linkage of black males to guns—a connection

cemented by vivid media images—rather than from generalized racial prejudice

against blacks.

55

With this crime–guns–blacks schema so prevalent, it is not

the claim that crime news reinforces a script in which crime is violent and perpetrators are black); see

also Mary Beth Oliver, Caucasian Viewers’ Memory of Black and White Criminal Suspects in the News,

49 J. C

OMM., Summer 1999, at 46, 46 (finding that white viewers presented with a newscast featuring a

white murder suspect were increasingly likely over time to misidentify the suspect as black); Mary Beth

Oliver & Dana Fonash, Race and Crime in the News: Whites’ Identification and Misidentification of

Violent and Nonviolent Criminal Suspects, 4 M

EDIA PSYCHOL. 137, 137 (2002) (finding that white

viewers presented with a newspaper crime brief featuring violent- and nonviolent-crime stories and

photographs of white and black criminal suspects had an increased likelihood later to misidentify the

black criminal suspects in the violent-crime stories); Travis L. Dixon, Black Criminals and White

Officers: The Effects of Racially Misrepresenting Law Breakers and Law Defenders on Television News,

10 M

EDIA PSYCHOL. 270, 270 (2007) (finding that test subjects were highly likely to assume that

unidentified perpetrators were black no matter what their prior level of news viewing and that heavy

viewers of news were more likely to say an unidentified police officer was white). Dixon’s finding that

unidentified police officers were more likely to be identified as white is consistent with the notion that

television viewing creates specific crime scripts. See id. Interestingly, Dixon’s finding that news viewing

did not moderate the likelihood of rating the unidentified suspect as black suggests that this link has

been made for all viewers and is chronically accessible. See id. at 281.

50. Joshua Correll et al., The Police Officer’s Dilemma: Using Ethnicity to Disambiguate Potentially

Threatening Individuals, 83 J. P

ERSONALITY & SOCIAL PSYCHOL. 1314, 1314 (2002) [hereinafter

Correll et al., Police Officer’s Dilemma]; see also Joshua Correll et al., The Influence of Stereotypes on

Decisions to Shoot, 37 E

UR. J. SOC. PSYCHOL. 1102, 1102, 1105 (2007) [hereinafter Correll et al.,

Decisions to Shoot] (replicating this study and adding a preliminary task in which subjects were asked

to read news stories about black or white criminals).

51. Correll et al., Police Officer’s Dilemma, supra note 50, at 1315–17.

52. Id. at 1319.

53. See id.; Correll et al., Decisions to Shoot, supra note 50, at 1102 (finding exposure to news

stories featuring black criminals increased shooting bias); see also Kang, supra note 46, at 1562–63

(describing how local television news can create associations between racial categories and violent

crime).

54. See B. Keith Payne, Prejudice and Perception: The Role of Automatic and Controlled Process in

Misperceiving a Weapon, 81 J. P

ERSONALITY & SOCIAL PSYCHOL. 181, 181 (2001) (finding participants

identified guns faster and misidentified tools as guns more often when first presented with photographs

of black faces than when first presented with photographs of white faces).

55. See id. It is worth noting that the shooting experiments show that black subjects, not just

whites, respond prejudicially—suggesting the depth to which this particular cultural equation

penetrates. See Correll et al., Police Officer’s Dilemma, supra note 50, at 1325; Correll et al., Decisions

to Shoot, supra note 50, at 1108–11. But see Kristin A. Lane et al., Implicit Social Cognition and Law, 3

A

NN. REV. L. & SOC. SCI. 427, 435 (2007) (reporting that the same is not true of the Implicit-Attitude

Test experiments, in which blacks respond quite differently from whites to subtle racial cues).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 105

surprising that there are consequences for how people think about politics and

public policy.

Researchers have probed the effects of media representations of race and

crime on whites’ fearfulness of crime and whites’ tendencies to support punitive

public policies, such as capital punishment and mandatory long sentences.

Empirical studies have explored the effects of overrepresentation of black

lawbreakers. Using both experimental and survey studies, researchers have

shown that exposure to images of black, male, criminal defendants increased

whites’ punitive attitudes toward crime, as well as their tendencies to endorse

dispositional explanations for criminal behavior and racist beliefs.

56

Dixon and

Azocar draw similar conclusions, finding that news coverage interacts with

“news use” (the amount of news-watching engaged in by TV viewers) to

influence judgments of the structural limitations that blacks face in the United

States, attitudes toward the death penalty, and views on culpability.

57

Other

work reveals conditional effects of exposure to racialized crime depending on

the racial mix of the neighborhoods in which individuals lived. Whites who lived

in homogeneously white neighborhoods endorsed punitive crime policy and

expressed more-negative stereotypes of blacks when exposed to a black suspect

in a violent crime story, whereas whites living in heterogeneous neighborhoods

were unaffected or were moved in the opposite direction.

58

Other studies show an interaction between media exposure and the ethnic

composition of a community in influencing fear of crime. In areas where whites

56. See Gilliam & Iyengar, supra note 20, at 560. In this study, people were exposed to a no-crime

story, a murder story with no information identifying the race of the perpetrator, a murder story with a

mug shot of a black perpetrator, or a murder story with a mug shot of a white perpetrator. Id. at 563.

The murder story was identical across conditions with the exception of the mug shot. Id. Whites

exposed to the black perpetrator showed significantly greater support for punitive remedies for crime

than those who did not view a crime story. Id. at 567–68. Exposure to the black-perpetrator and the no-

perpetrator conditions also increased dispositional attributions among whites. Id. There was no similar

effect among those who were exposed to the white perpetrator. Id. Gilliam and Iyengar also found that

all crime stories influence racial attitudes (including the white-mug-shot condition), though the effects

are greatest in the no-perpetrator condition, then the black-perpetrator condition, and then the white-

perpetrator condition. Id. at 567–68. Using data from the Los Angeles County Social Survey, the

researchers demonstrate that frequent viewers of television news (who presumably get this specific

script) are more punitive. Id. at 570–71. The survey results lend external validity to the experimental

results.

57. Travis L. Dixon & Cristina L. Azocar, Priming Crime and Activating Blackness: Understanding

the Psychological Impact of the Overrepresentation of Blacks as Lawbreakers on Television News, 57 J.

C

OMM. 229, 229 (2007) (finding that heavy viewers of television news who are faced with unidentified

(that is, no race given) suspects are less likely to say blacks face structural limits to success and more

likely to support the death penalty than heavy viewers who are exposed to noncrime stories; and that

exposure to crime news with a majority of black suspects leads people to evaluate a race-unidentified

suspect as more culpable, an effect that is enhanced among heavy news viewers); see also Travis L.

Dixon, Psychological Reactions to Crime News Portrayals of Black Criminals: Understanding the

Moderating Roles of Prior News Viewing and Stereotype Endorsement, 73 C

OMM. MONOGRAPHS 162,

162 (2006) (finding that, after exposure to a newscast featuring either a majority of black or

unidentified-race suspects, viewers who endorsed stereotypes of blacks were more likely to support the

death penalty than viewers who rejected stereotypes of blacks).

58. Franklin D. Gilliam, Jr. et al., Where You Live and What You Watch: The Impact of Racial

Proximity and Local Television News on Attitudes About Race and Crime, 55 P

OL. RES. Q. 755, 755,

760, 770. (2002).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

106 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

perceive that significant proportions of their neighbors are black or Latino,

heavy viewers of news, of “reality” crime shows, and of fictional crime shows

are all markedly more fearful of crime.

59

The media images—and other political and cultural forces—that cultivate

racialized fear and animosity influence public policies through these effects on

prejudice. Soss and his colleagues show that whites’ racial sentiments are

strongly related to their level of support for the death penalty.

60

Furthermore,

residential proximity heightens this effect. In the presence of large populations

of African Americans, whites’ racial antagonism is particularly associated with

high support of the death penalty.

61

If such a strong yet simple equation between

violent crime and blacks were not made in the media and in U.S. culture, such a

relationship would not emerge. After all, murder is murder, and capital

punishment does not inherently implicate race. Nonetheless, historical study

reveals clear relationships among support of capital punishment, racial

attitudes, and the racial composition of different states.

62

On the other side of

the ledger, Weitzer and Tuch show that blacks and Latinos are more likely than

whites to support police-reform policies, in part because of their greater

attention to media reports of police misconduct and the greater extent of their

direct experience with it.

63

Media coverage of crime primes racial sentiments, influencing evaluations of

both candidates and policies. For example, Valentino found that subjects

responded to TV news stories that included brief shots of black, Latino, or

Asian criminal suspects by lowering their ratings of President Clinton—even

59. See Sarah Eschholz, Ted Chirico & Marc Gertz, Television and Fear of Crime: Program Types,

Audience Traits, and the Mediating Effect of Perceived Neighborhood Racial Composition, 50 S

OC.

PROBS. 395, 395, (2003) (finding that viewers of local news, “reality,” or fictional crime shows who

perceive that they live in a neighborhood with a high percentage of blacks have an increased fear of

crime); see also Ted Chiricos et al., Perceived Racial and Ethnic Composition of Neighborhood and

Perceived Risk of Crime, 48 S

OC. PROBS. 322, 322 (2001) (finding that the perception that blacks or

Latinos live nearby influences the perceived risk of criminal victimization); Ted Chiricos et al., Fear, TV

News, and the Reality of Crime, 38 C

RIMINOLOGY 755, 755 (2000) (showing that local news is related to

fear of crime independent of measures of “reality”); Sorin Matei et al., Fear and Misperception of Los

Angeles Urban Space: A Spatial-Statistical Study of Communication-Shaped Mental Maps, 28 C

OMM.

RES. 429, 429 (2001) (finding that people in Los Angeles with heavy television-viewing habits have

increased fear of nonwhite and non-Asian populations). But see Kimberly Gross & Sean Aday, The

Scary World in Your Living Room and Neighborhood: Using Local Broadcast News, Neighborhood

Crime Rates, and Personal Experience to Test Agenda Setting and Cultivation, 53 J. C

OMM. 411, 419–21

(2003) (finding that viewing local television news does not cultivate fear of crime once neighborhood

crime rates and personal experience are taken into account).

60. Joe Soss et al., Why Do White Americans Support the Death Penalty? 65 J. P

OL. 397, 397 (2003).

61. Id. at 409.

62. See Eric P. Baumer et al., Explaining Spatial Variation in Support for Capital Punishment: A

Multilevel Analysis, 108 A

M. J. SOC. 844, 844 (2003) (“[R]esidents of areas with higher homicide rates, a

larger proportion of blacks, and a more conservative political climate are significantly more likely to

support the death penalty.”). See generally David Niven, Bolstering an Illusory Majority: The Effects of

the Media’s Portrayal of Death Penalty Support, 83 S

OC. SCI. Q. 671 (2002) (discussing the complexities

of public sentiments toward the death penalty).

63. Ronald Weitzer & Steven A. Tuch, Reforming the Police: Racial Differences in Public Support

for Change, 42 C

RIMINOLOGY 391, 409–12 (2004).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 107

though the stories did not mention Clinton or his policies.

64

Presumably, the

widespread publicity about Clinton’s sympathies for persons of color made

white subjects think of him when they perceived crime committed by young

men of color. The 1988 Bush presidential campaign took advantage of whites’

tendencies to automatically associate black young men and Latino young men

with crime and fear in its infamous “Willie Horton” and “Revolving Door”

political advertisements.

65

A related study showed that by merely inserting the

words “inner city” in a survey question about spending money on prisons as

opposed to antipoverty programs, whites’ racial thinking was stimulated to the

point that “racial conservatives” became more punitive, favoring prisons over

antipoverty programs.

66

The mental association between the term “inner city”

and threatening persons of color is apparently so strong that visual images (such

as those in George H.W. Bush’s 1988 campaign advertisements) or explicit

racial labels are not even needed to generate an effect on whites.

67

Physiological

evidence, moreover, also supports the notion that negative associations with

black persons, repeated vividly across the mass media, resonate quite deeply in

whites’ neural networks.

68

C. Race and Crime Representations

The research outlined in this subsection suggests that it would be entirely

inappropriate to generalize from the Duke lacrosse case about the media’s

normal depictions of race and crime. Systematic content analyses of media

depictions of crime and race suggest that the Duke lacrosse case—featuring

white, relatively privileged defendants—does not follow the typical pattern. The

evidence on race and crime news is quite strong, about as strong as any social-

science evidence in the field of communication and public opinion. We know of

no credible research suggesting that wealthy white defendants are

systematically subjected to more unfair coverage or pretrial publicity compared

with black defendants. Moreover, the evidence illustrating the effects of such

coverage suggests that patterns in the media place black defendants at a

64. Nicholas A. Valentino, Crime News and the Priming of Racial Attitudes During Evaluations of

the President, 63 P

UB. OPINION Q. 293, 293 (1999); see also Mark Peffley et al., Racial Stereotypes and

Whites’ Political Views of Blacks in the Context of Welfare and Crime, 41 A

M. J. POL. SCI. 30, 30 (1997)

(“Whites holding negative stereotypes are substantially more likely to judge blacks more harshly than

similarly described whites in the areas of welfare and crime policy.”).

65. See generally, K

ATHLEEN HALL JAMIESON, DIRTY POLITICS: DECEPTION, DISTRACTION,

AND

DEMOCRACY 15–42 (1992) (describing advertisements in the context of negative political

campaigning); T

ALI MENDELBERG, THE RACE CARD 134–68 (2001) (discussing the advertisements in

the context of racial stereotypes in political campaigns).

66. John Hurwitz & Mark Peffley, Playing the Race Card in the Post-Willie Horton Era: The Impact

of Racialized Code Words on Support for Punitive Crime Policy, 69 P

UB. OPINION Q. 99, 99, 108

(2005).

67. See id. at 109.

68. See William A. Cunningham et al., Separable Neural Components in the Processing of Black

and White Faces, 15 P

SYCHOL. SCI. 806, 806 (2004) (using brain-imaging technology to reveal that a

subliminal, black stimulus “lights up” the amygdala, the portion of the brain that is particularly

sensitive to fear).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

108 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

disadvantage because of the association built between blacks, crime, and guilt.

Preexisting racial schemas, therefore, worsen the general problem of prejudicial

pretrial publicity for blacks (and perhaps Latinos). Even in the absence of

specific prejudicial publicity about a given defendant’s case, the general nature

of crime news may prejudice potential jurors against minority defendants. By

contrast, white defendants relative to black defendants may benefit from a

greater (though not necessarily high) presumption of possible innocence.

69

IV

A

NALYSIS OF COVERAGE OF THE DUKE LACROSSE CASE

Just how did the media cover this case? Did the media depict the incident as

a metaphor for larger issues of race and class? Did coverage undermine the

presumption of innocence or appear to slant in favor of one side? To what

extent did the various parties receive positive or negative coverage? Was this an

example of egregious “liberal bias” or “political correctness” run amok in

media coverage, as some have suggested? In order to begin to answer these

questions, we conducted a systematic content analysis, in addition to a more

qualitative assessment of coverage. Media coverage is characterized according

to how the media dealt with the case over the full period that it received

attention in the news; distinctions are also made among time periods (early

coverage compared with coverage after the DNA results were released), among

different media outlets (comparing newspapers with television), and among

different sections of newspapers (distinguishing news from editorials and

commentary).

Before turning to the analysis, however, it is helpful to explore why this case

received more attention than an accusation of rape against three college

students might be expected to generate. A kind of “perfect storm” of events

reinforced the attractions of this case for national, not just local, media. What

contributed to this “storm”? District Attorney Michael Nifong publicly

condemned the students and provided a narrative that was irresistible for the

media. The racial element was an important component of the frame the

District Attorney developed, perhaps intentionally, since he was running for

election and needed to maximize his support within Durham’s large black

electorate.

69. It is also true that because police officers, district attorneys, and the citizen pool that supplies

juries are often dominated by whites, blacks may be more likely to be arrested, treated more rigorously

by the criminal-justice system, and convicted. Moreover, given their lower socioeconomic status, they

are likely to have less-sophisticated and less-able legal representation, and less-refined public-relations

strategies designed to soften up potential jury pools and put political pressure on district attorneys,

police, and judges to treat the defendants fairly. See, e.g., Donna Coker, Foreword: Addressing the Real

World of Racial Injustice in the Criminal Justice System, 93 J. C

RIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 827 (2003)

(comparing the empirical evidence of criminal-law enforcement to assumptions underlying Fourth

Amendment and Equal Protection clause jurisprudence); see also Jeffrey T. Ulmer et al., Prosecutorial

Discretion and the Imposition of Mandatory Minimum Sentences, 44 J. R

ES. CRIME & DELINQ. 427, 427

(2007) (“find[ing] that Hispanic males are more likely to receive mandatory minimum[] [sentences] and

that Black–White differences in mandatory application increase with county percentage Black”).

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 109

Moreover, the case had elements that played into stereotypes and standard

scripts about race and class—dynamics that were reinforced by Duke’s mostly

affluent, mostly white student body and faculty located in Durham, a small city

(population approximately 190,000) with a predominantly working-class and

poor population, forty-four percent of which is African American. Some black

leaders and citizens took up and pushed the case in light of its perceived racial

dynamics and town–gown tensions. Faculty and outside groups who saw this

alleged crime as symbolic of real race, class, and gender injustices—which

turned out not to be represented by this particular case—helped propel it

further. In addition, the story played into another cultural schema, one about

elite college sports, athletes behaving badly, and universities doing little to stop

it. Furthermore, Duke is a kind of “celebrity” university, one of a handful that

combines prestige for its academics (ranking eighth in the 2008 U.S. News and

World Report rankings)

70

with highly publicized, championship sports teams—

as personified by “Coach K,” the men’s basketball coach, who does

commercials for American Express and General Motors, among others. In this

sense, the lacrosse saga possessed an allure roughly analogous to that of the

O.J. Simpson murder or the Michael Vick dog-abuse cases. All this may help to

explain why the case obtained so much publicity and also some of the specific

themes that emerged in coverage.

71

A. Sample and Coding for Systematic Quantitative Analysis

Our analysis focuses on stories substantively dealing with this case in The

New York Times, USA Today, the Raleigh News & Observer, and NBC Nightly

News. This focus allows comparison of national newspaper outlets (The New

York Times and USA Today) with a local newspaper (the Raleigh News &

Observer) and comparison of newspaper coverage with network news.

72

We

examined news coverage from March 14, 2006, through April 15, 2007. This

period encompasses the initial accusation and runs until four days after all the

charges were dismissed—through the Sunday following the dismissal of charges,

so as to include the Sunday papers.

73

The sample of substantive coverage dealing

70. U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT, AMERICA’S BEST COLLEGES 2008, available at

http://colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/usnews/edu/college/rankings/brief/t1natudoc_brief.php.

71. Between the time of the event in March and the end of May 2006, CBS Evening News spent 30

minutes on the story, ABC World News 27½ minutes, and NBC Nightly News 21½ minutes. Few if any

events in Durham’s history (aside from Duke basketball) have received as much concentrated,

national-media attention. Yet it is important not to overstate the case. In May 2006, only 16% of the

public said they were following this story very closely, compared with 42% who said they were

following news about the situation in Iraq very closely, 69% who said they were following high gasoline

prices very closely, and 44% who said they were following immigration very closely. P

EW RESEARCH

CENTER FOR THE PEOPLE AND THE PRESS, PUBLIC ATTENTIVENESS TO NEWS STORIES: 1986–2006,

http://people-press.org/nii/bydate.php.

72. Neither cable news nor talk shows were included in the systematic content analysis, though

they will be discussed briefly below. Nor was the local Durham paper included, a paper that has come

under criticism for its coverage. See T

AYLOR & JOHNSON, supra note 1, at 65.

73. This sample was based on a LexisNexis search for all articles that included “Duke” within the

same paragraph as “lacrosse” during this time period.

This initial search generated several stories that

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

110 LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS [Vol. 71:93

with the case includes 86 articles from The New York Times, 40 from USA

Today, 321 from the News & Observer, and 21 stories on NBC Nightly News.

74

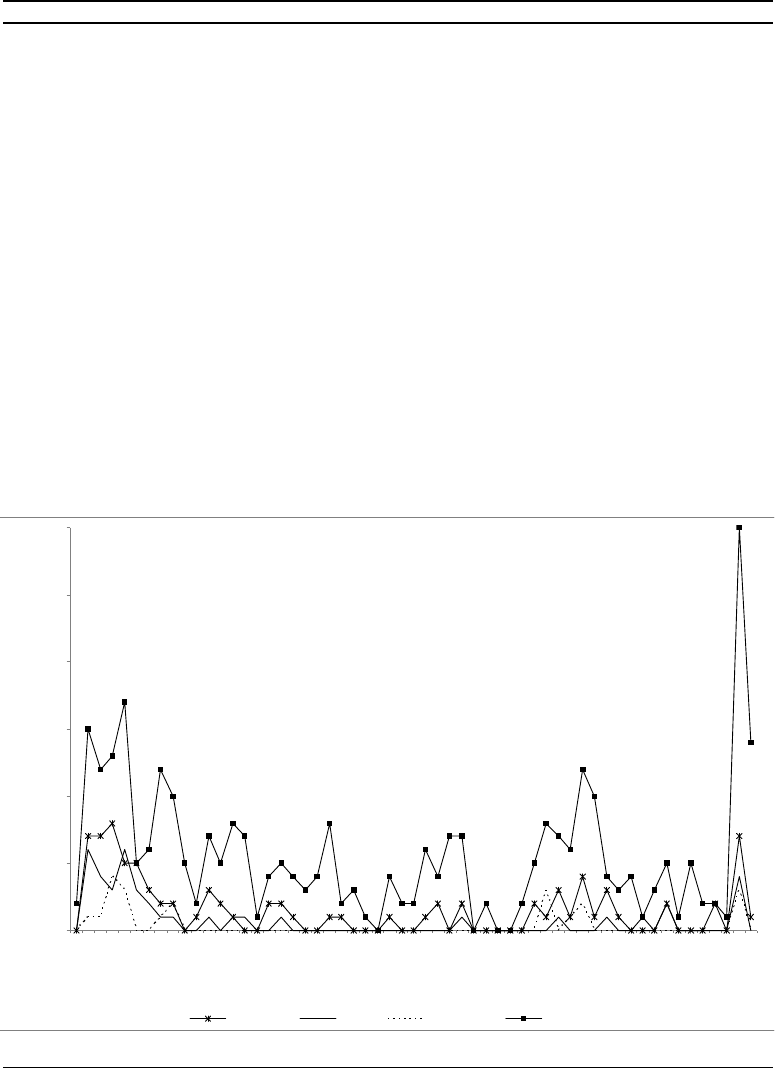

Figure 1 shows the amount of substantive coverage over time for this period

for each of these sources. Coverage waxes and wanes with events in the case; it

is always higher in the local paper, as one would expect. The national news paid

considerable attention in the very early period as the case initially unfolded and

indictments were issued (March 2006 through May 2006), returned to the case

when the rape charge was dropped and Nifong recused himself (December 2006

and January 2007), and gave considerable attention when the students were

cleared of all charges (April 2007).

Figure 1: Media Coverage of the Duke Lacrosse Case By Outlet: March 14,

2006, through April 15, 2007

did not substantively deal with the Duke lacrosse case; those with fewer than three paragraphs about

the incident were eliminated. Dropping these search results eliminated stories only peripherally dealing

with the case—such as those about the lacrosse team’s new fall season, their new coach, and the

women’s lacrosse team—while also removing one-sentence news summaries or other articles making

only a passing reference to the case. All letters to the editor and summaries describing an article inside

the paper were also removed from the sample. If an article ran less than three paragraphs, it was

included if the entire article dealt with the lacrosse case.

74. In all, NBC devoted thirty-four minutes of coverage to the case. Its depictions tended to track

major developments—there is no coverage between the indictment of the third defendant in May 2006

and the news that the rape charges had been dropped on December 23, 2006. This is somewhat less

time than the other two mainstream networks devoted to the story: ABC allocated just over forty-one

minutes to coverage of this case over this entire period, and CBS devoted nearly one hour to the case,

including an unusually lengthy ten-minute story on April 11, 2007.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Mar 1

9

- Ma

r

2

5

Apr

9

-

Apr 15

Apr 30 - May 6

M

a

y

21 - M

a

y 27

Jun 11 - J

u

n

1

7

Ju

l

2

-

Ju

l

8

Jul 23 - Jul 29

Aug 13 - A ug 19

Sept

3

- Sept 9

Sept

2

4 -

Sept 30

O

c

t

1

5

-

Oct 21

Nov 5

- Nov 11

N

ov

26

-

Dec

2

De

c

17 - De

c

23

J

an 7

-

Ja n 13

J

an

2

8

-

F

eb 3

Feb

18

- Feb

24

M

ar 1

1

- M

ar 17

Apr

1 - A

pr 7

Number of Stories

Ne w York Time s USA Today NBC Nightly News Ra l eigh News & Obse rver

05__ENTMAN & GROSS__CONTRACT PROOF_UPDATE.DOC 12/1/2008 3:14:01 PM

Autumn 2008] RACE TO JUDGMENT 111

In characterizing the nature of coverage, the coding strategy was two-fold.

First, it included examining the total number of substantive articles invoking

specific terms that might contribute to favorable or unfavorable evaluations of

the accuser and the accused, in addition to examining how often articles put the

coverage into a racial or class context to understand the larger frames used in

making sense of this event.

Second, the coding strategy included analyzing the degree to which news

stories provided information that would promote favorable or unfavorable

judgments of those associated with the prosecution and those associated with

the defense—that is, the degree to which the information would promote, in a

neutral audience member, a belief either in the defendants’ guilt or in their

innocence. Specifically, each paragraph was coded for the presence or absence

of information that might move a neutral reader toward the belief that the

players were guilty or toward the belief that they were innocent. Every

paragraph was thus coded as containing (1) only information that contributed to

the belief the players were guilty, (2) only information that contributed to the

belief the players were not guilty, (3) information that promoted both guilty and

nonguilty views, or (4) no information that might move a neutral reader in one

direction or the other.

75

This analysis provides a systematic basis for inferences