Journal of the Association for Information Systems Journal of the Association for Information Systems

Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 2

3-1-2002

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

David Gefen

Drexel University

Follow this and additional works at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Gefen, David (2002) "Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce,"

Journal of the Association for Information

Systems

, 3(1), .

DOI: 10.17705/1jais.00022

Available at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol3/iss1/2

This material is brought to you by the AIS Journals at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for

inclusion in Journal of the Association for Information Systems by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic

Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected].

27 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

David Gefen

Department of Management

LeBow College of Business

Drexel University

gefend@drexel.edu

ABSTRACT

The high cost of attracting new customers on the Internet and the relative difficulty in retaining

them make customer loyalty an essential asset for many online vendors. In the non-Internet

marketplace, customer loyalty is primarily the product of superior service quality and the trust that

such service entails. This study examines whether the same applies with online vendors even though

their service is provided by a website interface notably lacking a human service provider.

As hypothesized, customer loyalty to a specific online vendor increased with perceived better

service quality both directly and through increased trust. However, the data suggest that the five

dimensions of service quality in SERVQUAL collapse to three with online service quality: (1) tangibles,

(2) a combined dimension of responsiveness, reliability, and assurance, and (3) empathy. The first

dimension is the most important one in increasing customer loyalty, and the second in increasing

customer trust. Implications are discussed.

Keywords: E-commerce, trust, risk, customer loyalty, SERVQUAL

I. INTRODUCTION

Creating online customer loyalty—retaining existing customers—is a necessity for online vendors.

This study examines whether this goal can be achieved to some degree through increased customer

trust—the feeling of assurance—brought about through superior service quality. The study also

examines which aspects of service quality contribute to this trust in an online environment.

Attracting new customers costs online vendors at least 20% to 40% more than it costs vendors

serving an equivalent traditional market [Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. To recoup these costs and

show a profit, online vendors, even more so than their counterparts in the traditional marketplace,

must increase customer loyalty, which means convincing customers to return for many additional

purchases at their site. In the online book-selling market, for example, it takes over a year of repeat

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 28

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

purchases by a typical customer to recoup the average initial cost of attracting the customer to the

website. This is no exception. Among groceries and apparel websites, the figure is also over a year;

in the online consumer electronics and appliances market, it takes on average more than four years

to break even. Given these timeframes, increasing customer loyalty is an economic necessity for

many online vendors [Reichheld and Schefter 2000].

Customer loyalty, in general, increases profit and growth in many ways [Chow and Reed 1997;

Heskett et al. 1994] to the extent that increasing the percentage of loyal customers by as little as 5%

can increase profitability by as much as 30% to 85%, depending upon the industry involved

[Reichheld and Sasser 1990]—a ratio estimated to be even higher on the Web [Reichheld and

Schefter 2000]. The reason for this is that loyal customers are typically willing to pay a higher price

and are more understanding when something goes wrong [Chow and Reed 1997; Fukuyama 1995;

Reichheld and Sasser 1990; Reichheld and Schefter 2000; Zeithaml et al. 1996], and are easier to

satisfy because the vendor knows better what the customers’ expectations are [Heskett et al. 1994;

Reichheld and Sasser 1990; Zeithaml et al. 1996]. Indeed, the success of some well-known websites

can be attributed in part to their ability to maintain a high degree of customer loyalty. Part of the

success of Amazon.com, the leading online book-selling site, for example, is attributed to its high

degree of customer loyalty, with 66% of purchases made by returning customers [The Economist

2000]. Loyal customers are also more inclined to recommend the vendor to other customers,

increasing the customer base at no additional advertising expense [Heskett et al. 1994; Reichheld

and Sasser 1990; Zeithaml et al. 1996]. The success of some well-known websites, such as eBay,

has been in part thanks to their ability to cut the costs of attracting new customers through such a

referral system [Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. Indeed, one of the ways trust is built is through a

process of transference whereby individuals begin trusting unknown others because the unknown

others are trusted by a person they trust [Doney and Cannon 1997].

Related research suggests that in a non-Internet marketplace customer loyalty is based primarily

on customer trust [e.g., Fukuyama 1995; Reichheld and Sasser 1990] and on perceived service

quality [e.g. Heskett et al. 1994; Reichheld and Sasser 1990]. Recent case studies suggest that this

applies also to the customers of online vendors [Reichheld and Schefter 2000], but many questions

still remain open. Although service quality has been studied in an online environment, to the best of

our knowledge, there are no empirical studies examining the theory that service quality increases

customer loyalty through increased trust in the unique online environment where the service provider

with which the customer interacts is a machine interface rather than with a person. On the contrary,

previous research has questioned whether the traditional dimensions of service quality can be applied

to online service quality precisely because of this machine interface [e.g. Gefen and DeVine 2001;

Kaynama and Black 2000; Shankar et al. 2000; Young 2001; Zeithaml et al. 2001].

Accordingly, the objective of this study is to examine (1) whether service quality as measured

through SERVQUAL increases trust and thereby contributes to creating loyal customers among online

customers, and (2) whether the dimensionality of service quality as created for a non-Internet

marketplace, where there is a human service provider, applies to services provided by an online

service provider through a Web-page interface, i.e., without a human service agent. Answering these

questions is the objective of this study.

The study focused on veteran customers of Amazon.com. The data show that the five service

quality dimensions suggested by SERVQUAL [Parasuraman et al. 1985], an established and widely-

used measure of service quality that determines customer loyalty in a traditional marketplace setting

[Zeithaml et al. 1996], collapse into only three dimensions with an online service provider:

(1) tangibles, (2) a combined scale of reliability, responsiveness, and assurance, and (3) empathy.

29 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

The data indicate that the second dimension of service quality (responsiveness, reliability, and

assurance) increases customer trust. The data also indicate that customer trust, and to a lesser

degree service quality (tangibles), and cost-to-change to another vendor increase loyalty. Perceived

risk of doing business with the vendor did not significantly decrease customer loyalty.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

SERVICE QUALITY AND CUSTOMER LOYALTY

As a behavioral intention, customer loyalty deals with customer intentions to do more business

with the vendor and to recommend that vendor to other customers [Zeithaml et al. 1996]. One way

of increasing customer loyalty, suggested by case studies [e.g., Heskett et al. 1994] and by survey

research [e.g., Shankar et al. 2000; Zeithaml et al. 1996] is through superior service quality. Since

quality service is something that customers typically want and value, providing high quality service

should arguably increase their willingness to come back and do more business with the vendor.

Conversely, customers who experience low service quality will be more inclined to defect to other

vendors because they are not getting what they expect [Heskett et al. 1994; Reichheld and Sasser

1990; Reichheld and Schefter 2000; Watson et al. 1998]. Research indeed shows that in many

traditional companies, perceived service quality, as measured by adapted SERVQUAL scales,

strongly and directly influences customer loyalty [Zeithaml et al. 1996]. Service quality is crucial also

with online companies [Shankar et al. 2000; Zeithaml et al. 2001].

Quality Service is the customers’ subjective assessment that the service they are receiving is the

service that they expect [Parasuraman et al. 1985; Watson et al. 1998]. It is the subjective com-

parison that customers make between the quality of the service that they want to receive and what

they actually get. The widely-used SERVQUAL instrument [Parasuraman et al. 1985] identifies five

service quality dimensions that apply across industries [Zeithaml et al. 1996], although there is

empirical evidence that responsiveness, reliability, and assurance may actually be one factor [Llosa

et al. 1998]:

• Tangibles: This dimension deals with the physical environment. It relates to customer assess-

ments of the facilities, equipment, and appearance of those providing the service.

• Reliability: This dimension deals with customer perceptions that the service provider is providing

the promised service in a reliable and dependable manner, and is doing so on time.

• Responsiveness: This dimension deals with customer perceptions about the willingness of the

service provider to help the customers and not shrug off their requests for assistance.

• Assurance: This dimension deals with customer perceptions that the service provider’s behavior

instills confidence in them through the provider’s courtesy and ability.

• Empathy: This dimension deals with customer perceptions that the service provider is giving

them individualized attention and has their best interests at heart.

CUSTOMER TRUST AND CUSTOMER LOYALTY

Another determinant of customer loyalty is the degree of trust that the customers have in the

vendor [Chow and Reed 1997; Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. There are many definitions of trust in

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 30

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

the literature. Many definitions deal with the belief that the trusted party will be dependable [Kumar

et al. 1995a], will behave in a socially-appropriate manner [Zucker 1986], will fulfill the expected

commitments [Luhmann 1979; Rotter 1971], and will generally act in an ethical manner [Hosmer

1995] in situations where the trusting party depends on this behavior [Deutsch 1958; Meyer and Goes

1988; Rousseau et al. 1998]. In this study, based on previous research on trust in e-commerce

[Gefen 2000], trust is defined as the willingness to make oneself vulnerable to actions taken by the

trusted party based on the feeling of confidence or assurance, as discussed by Mayer et al. [1995]

and by Rousseau et al. [1998]. Trust is important when it is practically impossible to fully regulate the

business agreement and where it is consequently necessary to rely on the other party not to take

unfair advantage and not to engage in opportunistic behavior [Deutsch 1958; Fukuyama 1995;

Williamson 1985]. As such, trust is a crucial aspect of many long-term business interactions

[Dasgupta 1988; Fukuyama 1995; Gambetta 1988; Ganesan 1994; Gulati 1995; Kumar et al. 1995b;

Moorman et al. 1992; Williamson 1985].

Trust is also a significant antecedent of customers’ willingness to engage in e-Commerce with

a given vendor [Gefen 1997, 2000; Jarvenpaa and Tractinsky 1999; Kollock 1999; Reichheld and

Schefter 2000]. Customer trust in the online vendor is important because there is little guarantee in

an Internet environment that the online vendor will refrain from undesirable, unethical, opportunistic

behaviors, such as unfair pricing, presenting inaccurate information, distributing personal data and

purchase activity without prior permission, and the unauthorized use of credit card information [Gefen

2000; Kollock 1999]. Given these risks, customers who do not trust an online vendor will be less

inclined to do business with the vendor [Gefen 2000; Jarvenpaa and Tractinsky 1999] or to return for

additional purchases [Reichheld and Schefter 2000].

Trust plays this central role because of two possible, albeit overlapping, mechanisms: (1) it is a

social complexity reduction method [Gefen 2000], and (2) it reduces the perceived risk of doing

business with the vendor [Jarvenpaa and Tractinsky 1999]. As a social complexity reduction

mechanism, trust enables individuals to reduce the otherwise overpowering social complexity involved

in their interactions with other people. Luhmann [1979] points out that, in general, trust is essential,

because people are motivated to understand their social environment—in other words, to understand

the effect their behavior will have on others and what others will do. Achieving such an understanding

is hindered by the fact that other people are essentially independent agents whose behavior cannot

necessarily be predicted and may not even be rational. Nonetheless, since people need to under-

stand their social environment, they employ a variety of social complexity reduction mechanisms to

reduce the number of possible behaviors by others that they need to consider. In many cases, rules

and regulations (i.e., agreed-upon definitions of acceptable behavior) are enough. When these are

not enough, people reduce the social complexity, among other means, by assuming away many

possible undesirable behaviors that others may adopt. Assuming away such undesirable behaviors,

and so simplifying the social complexity, is the essence of trust [Luhmann 1979]. Accordingly, to the

trusting party, it is inconceivable that the trusted person might even consider certain undesirable

behaviors [Blau 1964]. Based on these ideas, research has shown that customer trust is a significant

antecedent of online purchase activity because it allows the customer to assume, rightly or not, that

the online vendor’s behavior will be as is expected [Gefen 2000].

Social complexity deals with a wide range of possible behaviors. Some of these place the trusting

party at a risk of being exposed not only to the inability to predict the behavior of others but also to

an explicit risk that these others may engage in inappropriate opportunistic behavior. The second

view of trust deals with this aspect, proposing that the main effect of trust is through reducing the

perceived risk that comes with exposure to possible opportunistic behavior by others: it is perceived

31 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

as less risky to do business with a trusted party [Deutsch 1958; Williamson 1985]. Trust is important

in the case of online customers, according to this view, because it reduces the customers’ perceived

risk that the online vendor will engage in undesirable behaviors. According to this view, trust deals

with social complexity reduction in the more limited context of perceived risk. Research supports both

these views of trust: it directly affects customers’ purchase intentions on the Internet [Gefen 2000],

and it affects customers’ purchase intentions through the reduction of perceived risk among

inexperienced users [Jarvenpaa and Tractinsky 1999].

SERVICE QUALITY AND CUSTOMER TRUST

How then can trust be built up among veteran customers? Luhmann [1979] and Blau [1964]

suggest that, in general, trust is built up when the trusted party behaves in a socially acceptable

manner that is in accordance with what is expected of that trusted party, and that, conversely, trust

is reduced when the trusted party does not behave accordingly without good reason. Since quality

service is something customers generally expect vendors to provide [Parasuraman et al. 1985;

Zeithaml et al. 1996], high quality service should arguably build customer trust, as a recent case study

with customers of online vendors indicates [Reichheld and Schefter 2000].

III. RESEARCH MODEL AND HYPOTHESES

Customer loyalty, in general, is about earning customer trust: customers who trust the vendor

will come back and will recommend the vendor to other customers; customers who do not trust the

vendor will not. This is even more so in the case of an online vendor because of the increased

uncertainty involved in commerce with such vendors: customers cannot assess the trustworthiness

of the salesperson through body language, nor can customers assess the vendor by the looks of the

store or the quality of the products by examining them [Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. Additional,

albeit indirect, support for this argument comes from research showing that the more customers,

including those with previous purchase experience with the vendor, trust the online vendor, the more

they are inclined to shop and to purchase with that same online vendor [Gefen 2000]. Accordingly,

it is hypothesized that:

H

1

: Customer trust in an online vendor increases customer loyalty to that vendor.

Customer trust is necessary for online purchases because, in general, trust reduces the per-

ceived risk and fear of being taken advantage of [Mayer et al. 1995; Williamson 1985]. Trust,

according to this view, should influence online purchasing through the reduction of the perceived risk

of being taken advantage of by the vendor [Jarvenpaa and Tractinsky 1999; Reichheld and Schefter

2000], because, in general, people expect less opportunistic behavior from those whom they trust

[Blau 1964; Williamson 1985]. Since online customers are exposed to increased risk of fraud and

of being taken advantage of, as the Better Business Bureau recently testified [Cole 1998], customer

trust, through its reduction of the perceived risk of doing business with the vendor, should increase

customer loyalty [Reichheld and Schefter 2000]:

H

2

: Perceived risk with an online vendor decreases customer loyalty to that vendor.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 32

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

H

3

: Customer trust decreases the perceived risk with an online vendor.

An alternative reason why customers return to an online vendor is based on utility: customers

will remain with a vendor because the cost of switching to another vendor is such that it is not worth

their while to switch [Chen and Hitt 2000; Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. Indeed, regarding ERP

consultants, the cost of changing to another vendor, independently of their trust in the vendor,

increases their loyalty to the vendor with whom they are used to working [Gefen and Govindarajulu

2001]. Although this cost-to-switch may not be the main reason why online customers are loyal

[Reichheld and Schefter 2000], it was included in the research model to allow for the evaluation of

the relative importance of customer trust and service quality on customer loyalty.

H

4

: Perceived switching costs to another online vendor will increase customer

loyalty.

Customer loyalty, in general, is also built up through good quality service: when customers get

high quality service, they are more likely to come back and to recommend the vendor to others

[Heskett et al. 1994; Reichheld and Sasser 1990; Reichheld and Schefter 2000; Zeithaml et al. 1996].

The same applies to online vendors [Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. In this study, service quality was

defined with an adapted SERVQUAL instrument because of its empirically validated effect on

customer loyalty across industry types [Zeithaml et al. 1996]. Arguably, the service dimensions

captured by SERVQUAL should also be important to online customers:

• Tangibles: This dimension of SERVQUAL deals with appealing physical facilities and with

human service providers who are dressed neatly. Although a customer of an online vendor

cannot assess these, this dimension should apply to online vendors through the appearance of

the website. The website is a tangible aspect of the online service that is partially comparable

to the appearance of any storefront or service counter [Berman and Green 2000]. Moreover, a

neat and appealing website is a tangible value in its own right just as a neat, well-organized, and

indexed directory or catalog is. Conversely, a cluttered and disorganized website is not a sign

of good service, just as a cluttered and disorganized storefront, service counter, or catalog is not.

In the case of a book-selling vendor, such as Amazon.com, the appealing interface, ease-of-use

and understandability of the website interface, and the clarity of the purchase procedures are

tangible service benefits [Gefen and Straub 2000].

• Reliability: This dimension deals with providing the service on time and as ordered. It is

perhaps among the most important aspects of service quality, in general, and is also a major

aspect of online service quality [Berman and Green 2000]. In the case of a book-selling vendor,

delivering the ordered products dependably and on time is an example of reliable service, just as

it is with a traditional bookstore.

• Responsiveness: This dimension deals with the human service provider’s ability to respond to

the customers in an accurate, error-free, helpful, and prompt manner. It is doubtful if automated

systems today can provide the kind of responsive service that salespeople can, but there are

some responsiveness aspects that also relate to websites: providing prompt service, providing

helpful guidance when problems occur, and telling customers accurately when the ordered

services will be performed or the products delivered.

33 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

1

It should be noted in this regard that this study deals with ongoing trust—trust that is created

through interaction. The study does not deal with swift trust, which is the initial trust people bring into

a relationship before they engage in the relationship [McKnight et al. 1998].

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

• Assurance: Here too it is doubtful if an automated system can provide the knowledge and

courtesy of human assistants measured in this dimension. Nonetheless, courteous help-screens,

and appropriate error messages and guidance boxes, among other means, can help customers

in a manner comparable to guidance signs and instructions in a regular store. Conversely, as

in a regular store, the lack of such apparatus may be interpreted as an indication of disregard

toward the customers. In the case of a book-selling vendor such as Amazon.com, assurance that

the vendor is knowledgeable and courteous can be shown through the system’s ability to guide

the customer through the process, and to supply additional beneficial services, such as

recommending additional books dealing with the same topic.

• Empathy: Many online vendors, including the one examined in this study, attempt to create a

personalized service through customized contents, personal greetings, and individualized e-mail.

Needless to say, these do not create the same empathy as human service providers, but they do

personalize the interaction with the vendor and provide individualized service to some degree.

Accordingly, it is hypothesized that these service dimensions and their predictive validity apply

also to online vendors. Hypotheses H

5.1-5.5

deal with the five dimensions of service quality in order:

tangibles, empathy, reliability, responsiveness, and assurance.

H

5.1–5.5

: Service quality increases customer loyalty.

Service quality should also increase customer trust [Reichheld and Schefter 2000]. Trust is

generally earned through continued successful interactions in which the trusting party’s expectations

are met or exceeded [Blau 1964; Ganesan 1994; Luhmann 1979; Moorman et al. 1992]. Conversely,

when these expectations are not met without a good reason, trust is ruined [Blau 1964]. Service

quality captures the essence of part of what makes such an interaction successful. It measures

whether the customers received the quality of service they expected (and presumably paid for) when

shopping. Thus, it is the success of these interactions as captured in part in customer assessments

about service quality that should build trust.

1

Extending this logic suggests that when customers,

online or not, experience service quality that is in accordance with what they expect, their trust

increases. Hypotheses H

6.1-6.5

deal with the five proposed dimensions of service quality in order:

tangibles, empathy, reliability, responsiveness, and assurance. These hypotheses relate to all the

dimensions of service quality, because research on SERVQUAL does not indicate whether the effects

of the different dimensions of service quality should be different [e.g., Parasuraman et al. 1985; Van

Dyke et al. 1999; and Zeithaml et al. 1996].

H

6.1-6.5

: Service quality increases customer trust

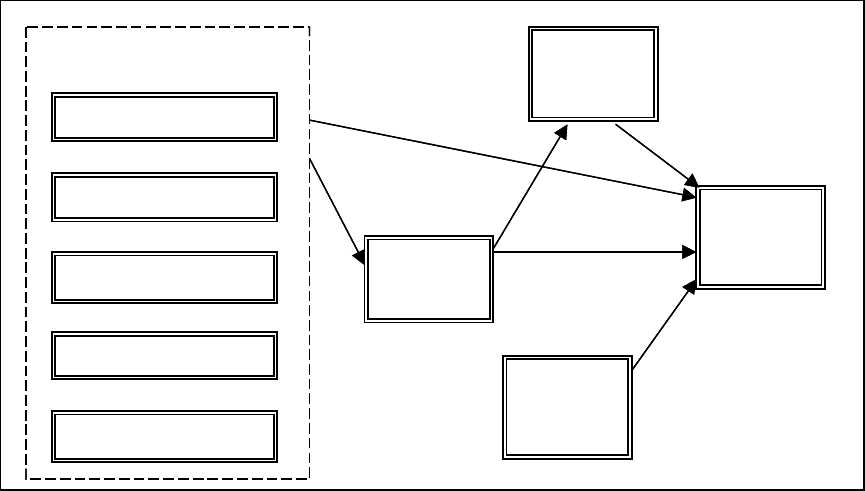

The research model is shown in Figure 1.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 34

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

Customer

loyalty

Perceived

Risk with

vendor

Cost to

Switch

Vendor

Customer

Trust

Tangibles

Empathy

Reliability

Service Quality:

H

1

H

2

H

4

H

5.1-5.5

H

3

H

6.1- 6.5

Assurance

Responsiveness

Customer

loyalty

Perceived

Risk with

vendor

Cost to

Switch

Vendor

Customer

Trust

Tangibles

Empathy

Reliability

Service Quality:

H

1

H

2

H

4

H

5.1-5.5

H

3

H

6.1- 6.5

Assurance

Responsiveness

Figure 1. Research Model

IV. RESEARCH METHOD

The research model was examined with a survey on loyalty to Amazon.com in the context of

online book purchase. The survey was administered to undergraduate and graduate students. The

data analysis was limited to data from students who were experienced shoppers at Amazon.com,

owing to the need to examine shoppers with prior experience.

INSTRUMENT DEVELOPMENT AND PRETEST

The study adapted existing validated scales and experimental procedures whenever possible.

The perceived service quality scale was adapted from SERVQUAL [Parasuraman et al. 1985], based

on the adaptation of the scale for information systems service quality [Watson et al. 1998].

SERVQUAL has been applied in previous research dealing with service quality measurements

relating to information technology and those providing it [e.g., Kettinger et al. 1995; Pitt et al. 1997;

and Watson et al. 1998]. It has also been applied to assess the degree to which service quality

across industries increases customer loyalty [e.g., Zeithaml et al. 1996].

There are two methods of applying SERVQUAL. It can be applied as a perceptions-only scale,

where the instrument is applied at one point in time as a snapshot of perceived current service quality

[e.g., Hartline and Ferrell 1996; Zeithaml et al. 1996], or it can be applied to assess the gap between

the service that customers expected and the service that they actually received [e.g., Watson et al.

35 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

2

The gap scores are calculated by subtracting each expectation item from its associated

perception item. There is some controversy, however, about the applicability of using gap scores in

SERVQUAL, because (1) gap scores introduce different measures, gap versus non-gap items, within

the same analysis, (2) gap score reliability is generally lower, (3) gap scales show problems with their

convergent validity, (4) there is some ambiguity concerning what respondents understand by

“expectations,” (5) averaging the items that compose each dimension to calculate scores is

problematic given their unstable factor patterns, and, most important regarding the objectives of this

study, (6) the predictive validity of the perceptions-only instrument is better [Van Dyke et al. 1999].

Additionally, the perceptions-only instrument shows better reliability [Hartline and Ferrell 1996]. In the

words of Parasuraman et al. [1994]: “Our own findings…as well as those of other researches…also

support the superiority of the perceptions-only measure from a purely predictive-validity standpoint”

(p. 120). (For a detailed discussion, see Cronin and Taylor 1994; Hartline and Ferrell 1996; Van Dyke

et al. 1999.)

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

1998].

2

The perceptions-only instrument is most appropriate when assessing the predictive validity

of service quality while the gap scale is most appropriate when diagnosing service pitfalls [Zeithaml

et al. 1996]. Accordingly, since a central objective of the study was to examine the extent to which

service quality influences customer trust and loyalty (i.e., to assess the predictive validity of service

quality), the current study applied the perceptions-only instrument. The adapted SERVQUAL

instrument used a seven-point scale based on Van Dyke et al. [1999] requesting an assessment of

“Compared to my desired service level.” Nonetheless, the validity of applying gap measures was

examined and compared with that of the perceptions-only scale in a pre-test with 49 students who

went through the same procedure as those participating in the primary data collection effort. The

pretest showed that both the perceptions-only scale and the gap scale formed three factors when

examined in an exploratory factor analysis, but that the factor loadings in the perceptions-only scale

showed better convergent and discriminant validity. Specifically, the pretest revealed three

dimensions of the perceptions-only scale: (1) tangibles, (2) a combined dimension of responsive-

ness, reliability, and assurance, and (3) empathy, with the perceptions-only items loading highly only

on their respective factor. The gap items of each of these theoretical dimensions, on the other hand,

did not load highly on only one factor.

Customer loyalty was measured with a scale adapted from the scale used by Zeithaml et al.

[1996] to examine the relationship between SERVQUAL and customer loyalty across industries.

Online customer trust was adapted from Gefen [2000], who studied the effect of customer trust on

the intention to use Amazon.com. The cost-to-switch vendor scale and the perceived-risk-with-vendor

scale were new scales built for this study. The latter two scales were built on the basis of themes that

came up in class discussions with MBA students experienced in purchasing at Amazon.com who

were attending an MIS management course. The themes reflecting cost-to-switch vendor dealt with

effort and required learning. These themes indeed resemble some of the “lock-in” techniques used

by online vendors [Chen and Hitt 2000]. Price manipulation was not among these themes, perhaps

because textbook prices are approximately the same among the major online vendors. The class

discussions took place more than six months before the data collection and so were assumed not to

influence students’ answers six months later in the unlikely case that a student from the MIS

management class was also in the class where the data would be collected. These two scales were

pre-tested together with the other scales. These items were assessed on a seven-point scale ranging

from Strongly Agree (1) to Strongly Disagree (7) with (4) being Neutral. The items used in the

experimental instrument are shown in Appendix A.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 36

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

DATA COLLECTION

The actual data collection focused on customers of Amazon.com, one of the largest and best-

known online vendors [The Economist 2000]. MBA and senior year undergraduate students in a

leading mid-Atlantic business school in the U.S. who were attending lectures in an Internet-connected

computer-lab were asked to volunteer to take part in the study. The students were not told at this

stage about the nature of the study except that it dealt with e-commerce. The students were

attending programming and database courses that did not deal in any way with e-commerce.

Although participation was voluntary, almost all of the students (response rate 97%) returned

completed questionnaires (n = 211). However, only questionnaires from students who indicated that

they had previously bought at Amazon.com were included in the study. Dropping the other

questionnaires was essential because respondents who had not bought at Amazon.com could hardly

be expected to assess the quality of service that Amazon.com provided them in the past. This

resulted in dropping 61 questionnaires and an effective sample size of 160 was obtained (76% of the

original questionnaires), of which 37% were women, 47% were men, and 16% did not indicate their

gender. The respondents were mainly either in their early 20s (n = 86) or late 20s (n = 40), with

several in their early 30s (n = 11). Of the respondents, 101 were undergraduates and 59 were

graduate students. Apart from age, there was no significant difference in a MANOVA that examined

all the questionnaire items between the undergraduates and graduate students (Wilks’ Lambda =

.70379, p-value = .775) or between men and women (Wilks’ Lambda = .60166, p-value = .286). The

respondents had previously bought at Amazon.com 4.75 times on average. This is not surprising,

given that textbook prices are sometimes cheaper at Amazon.com than in the university bookstore.

V. DATA ANALYSIS

The data were first examined with a Principal Components Factor (PCA) analysis (Varimax

rotation) to examine convergent and discriminant validity based on Hair et al. [1998]. The factor

analysis showed seven factors with eigenvalues above 1, explaining 80.43% of the variance. With

the exception of the SERVQUAL items, the items of each scale loaded highly only on one factor,

showing the convergent and discriminant validity of the scales [Hair et al. 1998]. The SERVQUAL

items loaded on three factors: (1) tangibles, (2) a combined factor reflecting reliability, respon-

siveness, and assurance, and (3) empathy. Previous research has also noted the unstable

dimensionality of SERVQUAL [Van Dyke et al. 1999]. Only one item, “Amazon.com has operating

hours that are convenient to users” (item SQ19), loaded on the wrong factor and was subsequently

dropped from the analysis. This item loaded on its expected factor (reliability, responsiveness, and

assurance) but more strongly on the tangibles factor. Given that Amazon.com operates on a 24-

hours-a-day, 7-days-a-week basis and that the customers know this, the cross loading, showing that

round-the-clock operating hours are part of the tangibles aspect of a website, in retrospect is not

surprising. Two other service quality items loaded highly on more than one factor: “Amazon.com has

the knowledge to do the job” (SQ17) and “Amazon.com understands the specific needs of their users”

(SQ22). Both items loaded the highest on their expected factors but also loaded highly (above the

.40 threshold [Hair et al. 1998]) on the tangibles factor. These two items were dropped from the

subsequent analysis in PLS. The descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The data show that

the respondents thought that the service Amazon.com provided was reliable, responsive, instilled a

sense of assurance in them, was tangible, and showed empathy. The respondents were quite

37 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

3

Since the items were measured on a scale with 1 being agree and 7 being disagree, lower

numbers in Table 1 indicate higher values.

4

When an equivalent stepwise regression was run with only customer trust and service quality,

customer loyalty was increased almost to the same extent (R

2

= .52) by only customer trust ($ = .60,

t = 8.71) and tangibles ($ = .21, t = 3.03).

5

The surprising lack of significant effect of tangibles and of empathy on customer trust and

customer loyalty was reexamined in a set of linear regressions. A regression of tangibles as a sole

independent variable and customer trust as the independent variable shows that tangibles does affect

both customer trust ($ = .58, t = 8.618, R

2

= .33) and loyalty ($ = .61, t = 9.444, R

2

= .37), as does

empathy ($ = .40, t = 4.587, R

2

= .16, and $ = .29, t = 3.212, R

2

= .09, respectively). However, when

the combined dimension of reliability, responsiveness, and assurance is added to the four

regressions, only the combined dimension is significant, suggesting that all three dimensions of

service quality increase both customer trust and loyalty, but that the combined dimension of reliability,

responsiveness, and assurance overshadows the other two dimensions. The other insignificant

effects were also reexamined. Cost to switch vendor when run as a sole independent variable in a

linear regression slightly increases customer loyalty ($ = .33, t = 4.355, R

2

= .11) while perceived risk

with the vendor slightly decreases it ($ = -.27, t = -3.525, R

2

= .07), suggesting that the effect of cost

to switch and of risk are overshadowed by trust and service quality.

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

trusting and loyal, and did not agree that there was a risk in doing business with Amazon.com or that

the cost-to-switch to another vendor would be high.

3

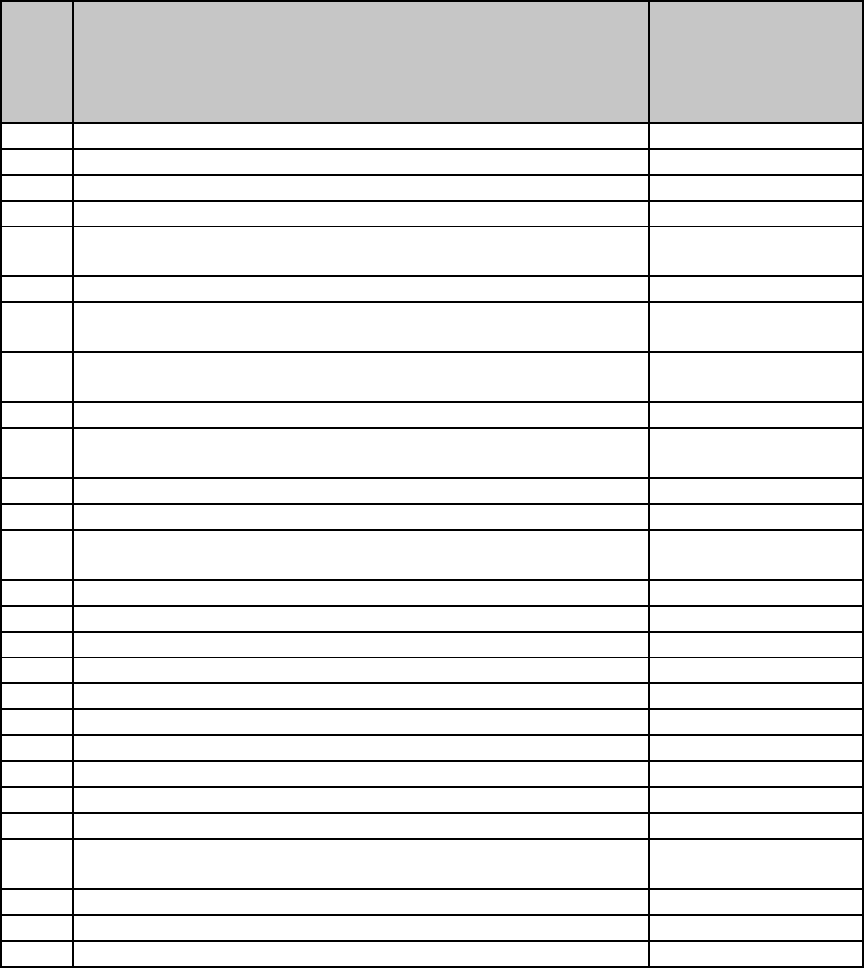

The hypotheses were tested using PLS. PLS is especially suited for this study because of its

exploratory nature and its emphasis on explaining variance [Gefen et al. 2000]. In the PLS analysis,

the dimensionality of SERVQUAL as revealed in the PCA was retained. The results of the analysis

are summarized in Figure 2. Note that because the SERVQUAL instrument collapsed to three

dimensions from its original five, hypotheses H

5.1-5.5

and H

6.1-6.5

, originally representing the five

dimensions, are accordingly represented by hypotheses H

5.1-5.3

and H

6.1-6.3

. Customer loyalty was

increased (R

2

= .59) by customer trust ($ = .48, t = 5.07), by tangibles ($ = .20, t = 3.24) and by cost-

to-switch vendor ($ = .19, t = 3.93), supporting H

1

, H

5.1

, and H

4

, respectively.

4

It was not significantly

affected by perceived risk with the vendor or by the other two dimensions of service quality, not

supporting H

2

, H

5.2,

and H

5.3

. The analysis also shows that perceived risk with the vendor was

decreased by customer trust (R

2

= .06, $ = -.24, t = -3.05), supporting H

3

. Customer trust itself was

increased by service quality but only by the combined service quality dimension of reliability,

responsiveness, and assurance (R

2

= .35, $ = .52, t = 4.10), supporting H

6.3

but not supporting H

6.1

and H

6.2

. All of the PLS reliability coefficients were above the equivalent suggested threshold of .80

for Cronbach’s " [Nunnally and Bernstein 1994].

Multi-collinearity was assessed by replicating the PLS analysis with stepwise linear regressions.

These linear regressions provided equivalent results and showed through the VIF (variable inflation

factor) statistic that there was little threat of multi-collinearity. The accepted threshold of VIF, which

indicates little multi-collinearity, is a value below 10 [Hair et al. 1998]. All of the stepwise linear

regression VIF values were below 3.1. The hypotheses’ test results are presented in Table 2.

5

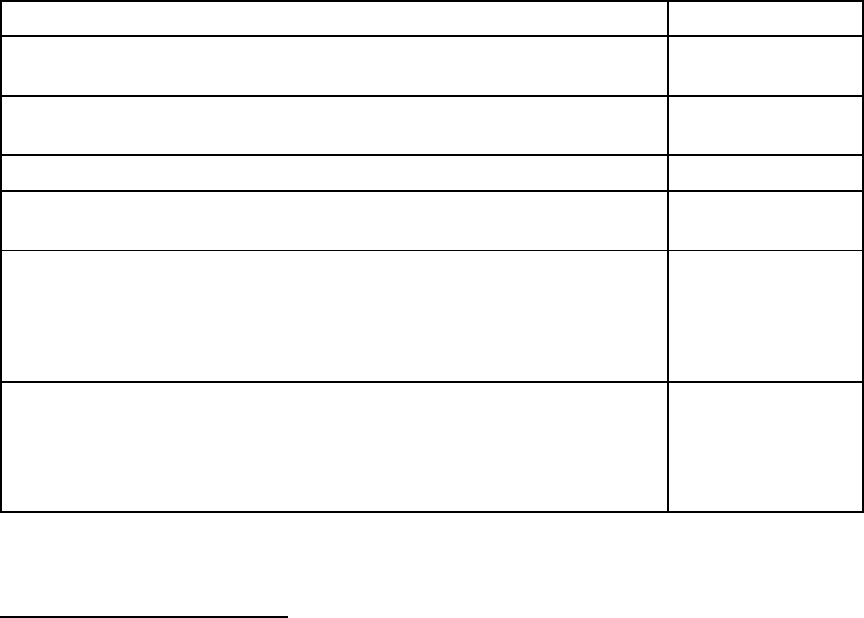

Table 1. Correlations of Latent Variables and Their AVE (in Diagonal)

Mean

(std.)

PLS

Reliability

a

Loyalty Risk

Switching

Costs

Customer

Trust Tangibles Empathy

Reliability

Responsiveness

Assurance

Loyalty 3.65

(1.40)

.922 0.902

Risk 4.40

(1.31)

.917 -0.181 0.885

Switching

Costs

4.90

(1.44)

.949 0.338 0.220 0.907

Customer

Trust

3.62

(1.31)

.858 0.695 -0.242 0.245 0.876

Tangibles 3.00

(1.42)

.928 0.509 -0.224 0.062 0.428 0.928

Empathy 3.39

(1.16)

.864 0.360 -0.192 0.192 0.426 0.502 0.891

Reliability

Responsiveness

Assurance

3.24

(1.13)

.987 0.607 -0.231 0.227 0.587 0.692 0.656 0.818

a

D = (E82)/((E8

2

)+ E,).

39 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

Customer

Loyalty

Perceived

Risk with

Vendor

Cost-to-

switch

Vendor

Customer

Trust

Tangibles

Empathy

Reliability,

Responsiveness,

Assurance

Service Quality:

R

2

= .59

R

2

= .06

R

2

= .35

H

1

= .48**

H

2

= not sig.

H

4

= .19**

H

5.1

= .20**

H

5.2

= not sig.

H

5.3

= not sig.

H

3

= -.24**

H

6.1

= not sig.

H

6.3

= .52**

H

6.2

= not sig.

Legend:

** p-value is smaller than .01

Supported hypothesis

Unsupported hypothesis

Customer

Loyalty

Perceived

Risk with

Vendor

Cost-to-

switch

Vendor

Customer

Trust

Tangibles

Empathy

Reliability,

Responsiveness,

Assurance

Service Quality:

R

2

= .59

R

2

= .06

R

2

= .35

H

1

= .48**

H

2

= not sig.

H

4

= .19**

H

5.1

= .20**

H

5.2

= not sig.

H

5.3

= not sig.

H

3

= -.24**

H

6.1

= not sig.

H

6.3

= .52**

H

6.2

= not sig.

Legend:

** p-value is smaller than .01

Supported hypothesis

Unsupported hypothesis

Legend:

** p-value is smaller than .01

Supported hypothesis

Unsupported hypothesis

Figure 2. Results of PLS Analysis

The discriminant and convergent validity of the scales was established, as required in PLS [Chin

1998; Gefen et al. 2000], by showing that the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of each latent

construct is larger than its correlation with the other latent constructs, and by showing in a

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) that each measurement item loads much more highly on its latent

construct than on any other latent construct. The AVE and latent variable correlations, together with

PLS reliability, are shown in Table 1. The CFA is shown in Appendix B.

VI. DISCUSSION

SUMMARY OF RESULTS

It is a truism that customer loyalty is an important goal of almost any profit-oriented business.

Case study results show that achieving customer loyalty depends to a large extent on the vendor’s

ability to build and maintain customer trust through quality service [Reichheld and Schefter 2000].

Nonetheless, previous empirical research has not examined whether these relationships hold

statistically nor has previous research examined their relative weight compared with other pertinent

issues such as cost to switch a vendor. This study addressed that gap, showing that even in an

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 40

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

online environment where there is no direct human service provider, service quality through increased

trust still contributes to the creation of loyal customers by statistically supporting these case study

propositions about e-commerce. The study also suggests that in the case of veteran customers and

an established online vendor, specifically Amazon.com, customer loyalty is primarily the product of

service quality and customer trust, itself the product of service quality, and to a lesser degree also by

cost-to-switch to another online vendor. The lesser weight of cost-to-switch is in accordance with

previous research that suggested that price sensitivity might actually be lower online [Shankar et al.

2000]. Regarding the first research question, therefore, the data support the hypotheses that service

quality through increased trust is a contributor to increased customer loyalty, and that this effect is

stronger than the cost to switch vendors.

Customer loyalty was also significantly correlated with decreased perceived risk in doing business

with the vendor, but this effect was not significant when customer trust, service quality, and cost-to-

switch vendor were added to the model. This supports the proposition that customer loyalty is mostly

about service quality and trust [Reichheld and Schefter 2000], a conclusion echoed in part also by the

popular press [e.g., Solomon 2000]. In that context, this study indicates that customer trust,

independently of and in addition to customer service, has a significant influence on customer loyalty.

The direct effect of customer trust on customer loyalty combined with the insignificant effect of

perceived risk imply, although clearly additional research is necessary to verify the issue, that at least

in the case of experienced online shoppers intending to buy low-touch merchandise, such as a book,

perceived risk is a negligible issue. Whether this applies also to new consumers or to products and

services where there is a greater ingredient of built-in risk requires additional study. It may be that

with other products and services where the real risk is acutely high, such as buying a house online,

trust will be irrelevant while perceived risk will be the predominant antecedent of loyalty. Nonetheless,

tentatively, these results imply that trust, at least in this limited domain of e-commerce where real risk

is relatively low, deals more with social complexity reduction than with the risk of being exposed to

opportunistic behavior. This tentative conclusion supports the view of trust in sociology [e.g., Blau

1964] and some MIS studies [e.g., Gefen and Govindarajulu 2001] as the basis of social interaction

whether or not risk is present.

With regard to the second research question about service quality, the study shows that the

service dimensions proposed by the SERVQUAL instrument can be adapted and still retain some of

their convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity in the context of online vendors who provide

service through websites, although these results should be regarded with caution and require

revalidation with additional sites and online vendors. The data suggest that service quality in the case

of an online vendor might be composed of three dimensions: (1) tangibles, (2) a combined dimension

of responsiveness, reliability, and assurance, and (3) empathy. Apparently, this collapsed dimen-

sionality is not unique to online service and may be a feature of SERVQUAL in general [Llosa et al.

1998]. The data also suggest that despite the lack of a human service provider, service quality does

increase customer trust and loyalty, although empathy is outweighed by the other service dimensions.

Specifically, the combined dimension of reliability, responsiveness, and assurance is the primary

dimension increasing customer trust while the tangibles dimension is the primary dimension building

customer loyalty. The apparent lesser role of empathy may be because the lack of human interaction

makes attentive personal understanding (empathy) a somewhat less important aspect of service

quality.

Tentatively, this may also explain the greater importance of the tangible side of service quality in

determining customer loyalty. Empathy is something people give to each other. It is not given by

machine interfaces, hence its insignificant role. Reliability, responsiveness, and assurance, on the

41 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

6

The high degree of shared variance among these dimensions has also been noted regarding

other information systems quality services [e.g., Van Dyke et al. 1999].

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

other hand, relate more to the human service providers behind the machine interface, hence their

effect is more related to the creation of trust, which captures an essence of how people relate to each

other. The tangibles dimension, on the other hand, while an appropriate aspect of service quality in

this case, does not deal with how people interact with each other, hence it directly increases loyalty,

possibly because it is a proxy for the quality of the vendor.

The typical lack of direct contact with a human service provider and the automated nature of the

service may also be the reason why the reliability, responsiveness, and assurance dimensions of

service quality collapsed into one dimension. Most customers’ interaction with Amazon.com only

involves inquiring about and then purchasing books through the website. Customer service in this

case, which is of relatively limited complexity compared with the service typically provided by a human

service agent, primarily means delivering the correct books to the correct address at the promised

date with the correct mailing option, wrapping, and billing. In this case, prompt and willing service with

error-free records (corresponding to the “responsiveness” dimension) is not so different from

dependable and timely service (corresponding to the “reliability” dimension) or from instilling

confidence through able and courteous service (corresponding to the “assurance” dimension).

6

Table 2. Hypotheses Test Results

Hypotheses Supported*

H

1

: Customer trust in an online vendor increases customer loyalty to that

vendor

Yes

H

2

: Perceived risk with an online vendor decreases customer loyalty to

that vendor.

Only independently

H

3

: Customer trust decreases the perceived risk with an online vendor. Yes

H

4

: Perceived switching costs to another online vendor will increase

customer loyalty

Yes

H

5

: Service quality increases customer loyalty

H

5.1

Tangibles service quality increases customer loyalty

H

5.2

Empathy service quality increases customer loyalty

H

5.3

Reliability, responsiveness, and assurance service quality

increases customer loyalty

Yes

Only independently

Only independently

H

6

: Service quality increases customer trust

H

6.1

Tangibles service quality increases customer trust

H

6.2

Empathy service quality increases customer trust

H

6.3

Reliability, responsiveness, and assurance service quality

increases customer trust

Only independently

Only independently

Yes

*Hypotheses marked “Only independently” are supported only when examined unaccompanied by

other hypotheses. See footnote 5 above.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 42

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

LIMITATIONS AND ADDITIONAL RESEARCH

It is necessary to put these results into perspective before discussing their implications. The

major limitation of this study is that data were collected with regard to only one online vendor in the

context of one specific online market, and a well-known vendor in an established market at that. This

may have skewed the results, explaining the insignificant role of perceived risk and why the effect of

trust was more than double that of cost-to-switch vendors. Moreover, examining only the online retail

book market may have also skewed the results and may explain the collapse of the five SERVQUAL

dimensions into only three dimensions. It is unclear at this stage whether the same pattern will occur

in other online markets, although the same collapsed structure of SERVQUAL has been recorded in

other research [Llosa et al. 1998]. Related to this limitation is the homogeneous nature of the sample.

Students represent a significant population of online book purchasers, as the proliferation of sites

specializing in students testifies. It is unclear at this stage, however, whether the results obtained

from this sample apply to other less computer-literate segments of the population and whether the

results can be generalized to other online products and services. Additional research with a sample

from a more diverse population and dealing with many other products and services as provided by

many online vendors is needed to examine these issues.

The research model examined linear relationships. It is conceivable, however, at least regarding

the effects of service quality on customer loyalty, that this relationship is not linear. Customer loyalty

may grow or decrease at more than a linear rate when service quality provided by a human service

provider is exceptionally good or exceptionally bad, respectively [Heskett et al. 1994]. It is possible

that the same applies also to the automated service provided by an online vendor. Amazon.com is

probably at neither of these extremes, at least not according to the data. Additional research with

online vendors who do provide exceptional service is therefore needed in order to expand the

research model to include exceptional service.

Additionally, the research model needs to be examined with less well-known online vendors to

verify that even with a vendor that lacks the credibility and name-recognition of Amazon.com, service

quality and trust still outweigh risk. Purchasing books from Amazon.com is probably less risky than

purchasing books from a relatively new and unknown online book vendor, and so generalizing the

model to other online vendors may require this additional verification. Moreover, since the importance

and role of service quality will change across industries [Zeithaml et al. 1996], and presumably the

same applies to online services as well, it is necessary to examine the research model with vendors

in other online industries, such as toys and auctions, to assess the generality of the model.

Research is also needed to refine the measurement of online service quality and to examine

other aspects of online service quality. SERVQUAL is an established and widely used instrument for

measuring service quality, but it was designed to assess service quality as provided by a human

agent. The dimensionality of service quality provided by an automated website is apparently some-

what different. Refining the instrument by adapting it to the unique characteristics of the automated

non-human service that online vendors provide is thus needed. Specifically, this relates to capturing

the other aspects of online service that are not part of the current version of SERVQUAL. These

include the time it takes the website to load and to respond, the existence and effectiveness of built-in

search engines, the usefulness of online links, and the absence of annoying banners, to mention but

a few. An adapted instrument that examines these is needed so that both industry and research can

properly assess online service quality with all its dimensionality.

The role of perceived risk also requires additional study. Risk avoidance varies across cultures

[Hofstede 1980], as does the relative importance of trust [Fukuyama 1995] and probably customer

43 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

expectations and assessments of service quality in general. Examining these possible cross-cultural

effects also requires additional research. Interestingly, in this regard, there was no gender effect in

the model, except regarding perceived risk with the vendor. This may be because gender differences

are less pronounced in a non-personal interaction [Coates 1986], such as those that occur in a typical

interaction with an online vendor. Additional research is necessary in this area in order to assess

whether this is the case.

Last but not least, the data collected in this study are cross-sectional survey data. The collection

of data from customers at only one point in time makes the attribution of causation only hypothetical.

Consequently, the study did not examine actual causation but only corroborated the correlations

implied by its theory base. There is not and there cannot be proof of causation with the kind of data

analyzed [Cook and Campbell 1979]. The use of self-reported measures may also have contributed

to some degree of bias in the high R

2

that were obtained. Additionally, the collection of data from

relatively young adults may have skewed the results.

Another aspect of the study that requires additional research is how trust is created online. This

study examined one aspect of it, namely perceived service quality. There are many other aspects

that contribute to the creation of trust in general. Some of these clearly apply to aspects such as

disposition to trust [McKnight et al. 1998; Rotter 1971] and familiarity [Gefen 2000]. There are many

other aspects of online service quality that are not captured by SERVQUAL [Kaynama and Black;

2000; Meyerson et al. 1996; Shankar et al. 2000], such as ease of use and the lack of annoying

banners [Gefen and DeVine 2001]. Another aspect that could contribute to customer trust is

perceived security, which is brought about through encryption, protection, verification, and

authentication, including e-mail confirmations and user-friendly interfaces [Chellappa and Pavlou

2001]. These topics were beyond the scope of this research. Additional research tying all of the

issues together as antecedents of online trust is necessary.

IMPLICATIONS

This study corroborates the importance of service quality in creating customer loyalty with online

vendors, although caution should be applied in generalizing the results because of the reputation of

the online vendor examined, especially with regard to the apparently less significant role of risk. In

this regard, the study indicates just how important service quality and customer trust are: over half

the variance of customer loyalty is explained primarily through service quality and the customers’ trust

that it entails. Customers of online vendors apparently value service quality, even if the entity they

interact with is an automated website rather than another human being.

This is an important point because, in general, service quality creates loyal customers who in their

turn, being more profitable to the vendor, allow the vendor to outperform even competitors with

smaller operating expenses. Accordingly, with traditional vendors it is more advisable to concentrate

on creating a trust-based relationship with loyal customers through service quality than to concentrate

on gaining new customers [Reichheld and Sasser 1990]. Although more than one study is necessary

to make the sweeping statement that service quality should be a central part of online vendors’

strategy, the results of this one study, to the extent that they can be generalized, do support this view.

But what is service quality? On what should online vendors concentrate, if they wish to increase

it? The study also suggests some guidelines here. Apparently, the tangibles dimension directly

increases customer loyalty, while the responsive, reliable, and assurance aspect of online service

quality is more important in increasing customer trust and through it customer loyalty. This need to

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 44

7

Editor’s Note: The following reference list contains the address of World Wide Web pages.

Readers who have the ability to access the Web directly from their computer or are reading the paper

on the Web can gain direct access to these references. Readers are warned, however, that

1. These links existed as of the date of publication but are not guaranteed to be working

thereafter.

2. The contents of Web pages may change over time. Where version information is provided

in the References, different versions may not contain the information or the conclusions references.

3. The authors of the Web pages, not JAIS, are responsible for the accuracy of their content.

4. The author of this article, not JAIS, is responsible for the accuracy of the URL and version

information.

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

invest in the tangible aspects of the website as a way of increasing customer loyalty is echoed in other

research dealing with online shopping [Shankar et al. 2000]. Specifically, tangibles deals with the

state-of-the-art appearance of the website, while the responsive, reliable, and assurance dimension

relates to delivering the products on time, as promised, and without error. Nonetheless, the empathy

aspects of online service quality, at least with regard to this vendor, also significantly affected both

trust and loyalty and so should not be discarded as unimportant.

The current study also examined two aspects of trust: whether it directly affects customer

intentions, in this case loyalty, or whether this is done indirectly through reduced risk. Additional

research is needed in this regard before a firm conclusion can be drawn, but in the case of returning

customers to Amazon.com, which might because of its size and renown be a special case, the study

shows that customers’ trust directly increased their loyalty. This suggests that customer trust might

encourage e-commerce activity primarily in this case through social complexity reduction rather than

through the reduction of perceived risk.

Last but not least, previous research has highlighted the importance of customers’ trust [e.g.,

Gefen 2000; Jarvenpaa and Tractinsky 1999], on the one hand, and of service quality [Reichheld and

Schefter 2000], on the other, as antecedents of e-commerce. This study extends these findings,

showing the importance of trust also among veteran customers and its subsequent significance for

customer loyalty. The study also shows that service quality is an antecedent of trust, helping to tie

together the literature on service quality with that on online trust. Superior service in many industries

creates trust and loyalty because it is an integral part of many products and services. The data show

that this is probably true also for at least parts of the online marketplace where service quality and

trust might be the more important aspects in increasing customer loyalty.

Editor’s Note: This article was received on October 10, 2001 and was with the author

one month for two revisions. Phillip Ein-Dor was the editor.

VII. REFERENCES

7

Berman, D. K., and H. Green. “Cliff-Hanger Christmas,” Business Week, October 23, 2000 (available

at http://www.businessweek.com/2000/00_43/b3704040.htm, accessed April 30, 2002).

Blau, P. M. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley, 1964.

Chellappa, R. K., and P. A. Pavlou. “Perceived Information Security, Financial Liability, and

Consumer Trust in Electronic Commerce Transactions,” Department of Information and

Operations Management, Marshall School of Business, University of Southern California, 2001.

45 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

Chen, P.-Y. S., and L. M. Hitt. “Switching Cost and Brand Loyalty in Electronic Markets: Evidence

from On-line Retail Brokers,” in Proceedings of the Twenty-First International Conference on

Information Systems, W. J. Orlikowski, S. Ang, P. Weill, H. C. Krcmar, and J. I. DeGross (eds.),

Brisbane, Australia, December 14-17, 2000, pp. 134-144.

Chin, W. W. “The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling,” in Modern

Methods for Business Research, G. A. Marcoulides (ed.), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates, 1998, pp. 295-336.

Chow, S., and H. Reed. “Toward an Understanding of Loyalty: The Moderating Role of Trust,”

Journal of Managerial Issues (9:3), 1997, pp. 275-398.

Coates, J. Women, Men and Languages: Studies in Language and Linguistics, London: Longman,

1986.

Cole, S. J. “Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Trade and Consumer

Protection Committee on Commerce, U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.,” 1998,

(available at www.bbb.org/alerts/cole.asp; accessed April 30, 2002).

Cook, T. D., and D. T. Campbell. Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field

Settings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

Cronin, J. J., and S. A. Taylor. “SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL: Reconciling Performance-based

and Performance-Minus-Expectations Measurements of Service Quality,” Journal of Professional

Services Marketing (20:2), 1994, pp. 125-131.

Dasgupta, P. “Trust as a Commodity,” in Trust, D. G. Gambetta (ed.), New York: Basil Blackwell,

1988, pp. 49-72.

Deutsch, M. “Trust and Suspicion,” Conflict Resolution (2:4), 1958, pp. 265-279.

Doney, P. M., and J. P. Cannon. “An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller

Relationships,” Journal of Marketing (61:2), 1997, pp. 35-51.

Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, New York: The Free Press,

1995.

Gambetta, D. G. (ed.). Can We Trust Trust?, New York: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

Ganesan, S. “Determinants of Long-Term Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships,” Journal of

Marketing, (58) April 1994, pp. 1-19.

Gefen, D. Building Users’ Trust in Freeware Providers and the Effects of this Trust on Users’

Perceptions of Usefulness, Ease of Use and Intended Use, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation,

Georgia State University, 1997.

Gefen, D. “E-Commerce: The Role of Familiarity and Trust,” Omega: The International Journal of

Management Science (28:6), 2000, pp. 725-737.

Gefen, D., and P. DeVine “Customer Loyalty to an Online Store: The Meaning of Online Service

Quality,” Proceedings of Twenty-Second International Conference on Information Systems, S.

Sarker, V, Storey, and J. I. DeGross (eds.), New Orleans, December 16-19, 2001, pp. 613-617.

Gefen, D., and C. Govindarajulu. “ERP Customer Loyalty: An Exploratory Investigation Into The

Importance of a Trusting Relationship,” Journal of Information Technology Theory & Application

(3:1), 2001, pp. 1-18.

Gefen, D., and D. W. Straub “The Relative Importance of Perceived Ease-of-Use in IS Adoption: A

Study of e-Commerce Adoption,” Journal of the AIS (1:8), 2000, pp. 1-30.

Gefen, D., D. Straub, and M-C. Boudreau. “Structural Equation Modeling and Regression: Guidelines

for Research Practice,” Communications of the AIS (4:7), 2000, pp. 1-70.

Gulati, R. “Does Familiarity Breed Trust? The Implications of Repeated Ties for Contractual Choice

in Alliances,” Academy of Management Journal (38:1), 1995, pp. 85-112.

Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51 46

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

Hair, J. F. J., R. E. Anderson, R. L. Tatham, and W. C. Black. Multivariate Data Analysis with

Readings (Fifth Edition), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998.

Hartline, M. D., and O. C. Ferrell “The Management of Customer-Contact Service Employees: An

Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Marketing (60), October 1996, pp. 52-70.

Heskett, J. L., T. O. Jones, G. W. Loveman, W. E. J. Sasser, and L. A. Schlesinger. “Putting the

Service-Profit Chain to Work,” Harvard Business Review (72:2), 1994, pp. 164-174.

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values, London:

Sage Publications, 1980.

Hosmer, L. T. “Trust: The Connecting Link Between Organizational Theory and Philosophical

Ethics,” Academy of Management Review (20:2) 1995, pp. 379-403.

Jarvenpaa, S. L., and N. Tractinsky “Consumer Trust in an Internet Store: A Cross-Cultural

Validation,” Journal of Computer Mediated Communication (5:2), 1999, pp. 1-35.

Kaynama, S. A., and C. I. Black. “A Proposal to Assess the Service Quality of Online Travel

Agencies: An Exploratory Study,” Journal of Professional Services Marketing (21:1), 2000, pp.

63-88.

Kettinger, W. J., C. C. Lee, and S. Lee. “Global Measures of Information Service Quality: A Cross-

National Study,” Decision Sciences (26:5), 1995, pp. 569-588.

Kollock, P. “The Production of Trust in Online Markets,” Advances in Group Processes (16), 1999,

pp. 99-123.

Kumar, N., L. K. Scheer, and J.-B. E. M. Steenkamp. “The Effects of Perceived Interdependence on

Dealer Attitudes,” Journal of Marketing Research (17), 1995a, pp. 348-356.

Kumar, N., L. K. Scheer, and J.-B. E. M. Steenkamp. “The Effects of Supplier Fairness on Vulnerable

Resellers,” Journal of Marketing Research (17), February 1995b, pp. 54-65.

Llosa, S., J.-L. Chandon, and C. Orsingher. “An Empirical Study of SERVQUAL’s Dimensionality,”

The Service Industries Journal (18:2), 1998, pp. 16-44.

Luhmann, N. Trust and Power, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, 1979.

Mayer, R. C., J. H. Davis, and F. D. Schoorman. “An Integration Model of Organizational Trust,”

Academy of Management Review (20:3), July 1995, pp. 709-734.

McKnight, D. H., L. L. Cummings, and N. L. Chervany. “Initial Trust Formation in New Organizational

Relationships,” Academy of Management Review (23:3), 1998, pp. 472-490.

Meyer, A. D., and J. B. Goes. “Organizational Assimilation of Innovations: A Multilevel Contextual

Analysis,” Academy of Management Journal (31:4), 1988, pp. 897-923.

Meyerson, D., K. E. Weick, and R. M. Kramer. “Swift Trust and Temporary Groups,” in Kramer, R.M.

and T.R. Tyler (eds.), Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1996, pp. 166-195.

Moorman, C., G. Zaltman, and R. Deshpande. “Relationships Between Providers and Users of

Market Research: The Dynamics of Trust Within and Between Organizations,” Journal of

Marketing Research (29), August 1992, pp. 314-328.

Nunnally, J. C., and I. H. Bernstein. Psychometric Theory (Third Edition), New York: McGraw-Hill,

1994.

Parasuraman, A., V. A. Zeithaml, and L. L. Berry. “A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its

Implications for Future Research,” Journal of Marketing (40), Fall 1985, pp. 41-50.

Parasuraman, A., V. A. Zeithaml, and L. L. Berry. “Reassessment of Expectations as a Comparison

Standard in Measuring Service Quality: Implications for Future Research,” Journal of Marketing

(58), January 1994, pp. 111-124.

Pitt, L. F.,R. T. Watson, and C. B. Kavan. “Measuring Information Systems Service Quality:

Concerns for a Complete Canvas,” MIS Quarterly (21:2), 1997, pp. 209-221.

47 Journal of the Association for Information Systems (Volume 3, 2002) 27-51

Customer Loyalty in E-Commerce

by D. Gefen

Reichheld, F. F., and W. E. J. Sasser. “Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services,” Harvard

Business Review (68:5), 1990, pp. 2-9.

Reichheld, F. F., and P. Schefter. “E-Loyalty: Your Secret Weapon on the Web,” Harvard Business

Review (78:4), 2000, pp. 105-113.

Rotter, J. B. “Generalized Expectancies for Interpersonal Trust,” American Psychologist (26), May

1971, pp. 443-450.

Rousseau, D. M.,S. B. Sitkin, R. S. Burt, and C. Camerer. “Not So Different After All: A Cross-

Discipline View of Trust,” Academy of Management Review (23:3), 1998, pp. 393-404.

Shankar, V., A. K. Smith, and A. Rangaswamy. “The Relationship Between Customer Satisfaction

and Loyalty in Online and Offline Environments,” EBusiness Research Center Working Paper,

02-2000, 2000 (available at http://www.ebrc.psu.edu/publications/papers/pdf/2000-02.pdf,

accessed April 30, 2002).

Solomon, M. “Service Beats Price on the Web, Study Finds,” Computerworld, 2000 (available at

http://www.computerworld.com/cwi/story/0,1199,NAV47_STO45848,00.html, accessed

April 30, 2002).

The Economist. “E-Commerce: Shopping Around The World,” February 26, 2000, pp. 5-54.

Van Dyke, T. P., V. R. Prybutok, and L. A. Kappelman. “Cautions on the Use of the SERVQUAL

Measure to Assess the Quality of Information Systems Service,” Decision Sciences (30;3), 1999,

pp. 877-891.

Watson, R. T., L. F. Pitt, and C. B. Kavan. “Measuring Information Systems Service Quality:

Lessons From Two Longitudinal Case Studies,” MIS Quarterly (22:1), 1998, pp. 61-79.

Williamson, O. E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism, New York: Free Press, 1985.

Young, M. B. “What Customers Want Online,” Marketing Science Institute, 2001 (available at

http://www.msi.org/msi/insights/ins00f-c.cfm, accessed April 30, 2002).

Zeithaml, V. A., L. L. Berry, and A. Parasuraman. “The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality,”

Journal of Marketing (60), April, 1996, pp. 31-46.

Zeithaml, V. A., A. Parasuraman, and A. Malhotra. “A Conceptual Framework for Understanding e-

Service Quality: Implications for Future Research and Managerial Practice,” Marketing Science

Institute, 2001 (available at http://www.msi.org/msi/publication_summary.

cfm?publication=00-115, accessed April 30, 2002).

Zucker, L. G. “Production of Trust: Institutional Sources of Economic Structure, 1840-1920,” in

Research in Organizational Behavior, B. M. Staw and L. L. Cummings (eds.), Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press, 1985, pp. 53-111.

VIII. ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David Gefen is an assistant professor of MIS at Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, where he

teaches Strategic Management of IT, Database Analysis and Design, and VB.NET. He received his

Ph.D. degree in CIS from Georgia State University and a Master of Sciences from Tel-Aviv University.

His research focuses on psychological and rational processes involved in ERP and e-commerce

implementation management. David’s wide interests in IT adoption stem from his 12 years of