MANAGING DISASTERS

AT THE COUNTY LEVEL:

A NATIONAL SURVEY

MARCH 2019

Emergency Management in County Government: A National Survey

March 2019

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 2

Survey Findings ....................................................................................................................................... 3

Organizational Structure ..................................................................................................................... 3

Reporting Structure ......................................................................................................................... 3

Staffing ............................................................................................................................................ 3

Professional Development ............................................................................................................... 4

Budget and Funding ............................................................................................................................ 4

Local Funding Sources ..................................................................................................................... 4

Federal Resources ........................................................................................................................... 5

State & Other Sources ..................................................................................................................... 5

Partnerships ........................................................................................................................................ 6

Planning .............................................................................................................................................. 6

Coordination Across Plans ............................................................................................................... 6

Special Populations .......................................................................................................................... 7

Use of Technology ........................................................................................................................... 8

Preparedness ....................................................................................................................................... 9

Preparedness Levels by County Agency and Community Groups ...................................................... 9

Mitigation ......................................................................................................................................... 10

Response ........................................................................................................................................... 11

Social Media .................................................................................................................................. 12

Other Communication Channels .................................................................................................... 12

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................ 13

Methodology ........................................................................................................................................ 13

Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 14

Appendix A: Glossary ............................................................................................................................ 14

Appendix B: Data Tables ....................................................................................................................... 20

Appendix C: County Survey Respondents ............................................................................................. 35

Appendix D: Survey Instrument ............................................................................................................ 38

Executive Summary

In May 2018, NACo conducted a survey to assess key aspects of county emergency management,

including organizational structure, budgets and funding, personnel and training, use of technology and

ways counties collaborate with other government entities and nongovernmental organizations. NACo

received completed responses from 397 counties in June 2018, representing all census divisions and 45

of the 50 states. The responding counties ranged in size from nearly 500 residents to more than 4.6

million, thus allowing NACo to identify general trends for small, medium and large counties. Of large

counties – or counties with populations of over 500,000 – 26 out of 131 responded. Of medium counties

– or counties with populations ranging from 50,000 to 500,000 – 126 out of 821 responded. Of small

counties – or small counties with populations of under 50,000 – 245 out of 2,117 responded.

There are several major findings of this survey:

• Nearly three quarters of counties indicate that their chief emergency management official

reports directly to the county elected official(s) – as opposed to reporting to county

administrative staff.

• 95 percent of counties formally endorse the National Incident Management System (NIMS) and

over 90 percent of county Emergency Management Agency (EMA) employees have completed

the NIMS training program.

• 62 percent of counties have adopted administrative and financial procedures that allow the

EMA to expediently request, apply for, receive, manage and expend funds during a local

emergency or disaster.

• The majority of counties (over 90 percent) maintain insurance against disaster damage for

buildings and infrastructure.

• At the federal level, counties most often engage FEMA – on recovery and education and training

– and NOAA – on education and training and planning – on emergency management.

• Counties engage with other local governments and organizations on planning more than three

times as often as they do on response – the phase on which they next most engage.

• 99 percent of counties report having an Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) and Hazard

Mitigation Plan (HMP). Additionally, 56 percent of counties report that they have integrated

their HMP into their county comprehensive plan.

• About two-thirds of counties use social media to communicate risk before and after a disaster;

although 12 percent of counties do not have social media accounts.

• 64 percent of counties have held a county-wide disaster preparedness drill within the past year.

19 percent have not done so in more than two years.

• While 77 percent of counties have pre-designated shelters for disaster evacuees, only 8 percent

indicate that they have adequate housing stock to support temporary housing for residents,

non-local volunteers, federal employees, etc.

• 22 percent of county respondents indicate that they do not regulate land use and 24 percent

indicate that they do not regulate buildings codes. Correspondingly, 6 percent of counties report

that they are not legally allowed to regulate local land use per state law and 8 percent report

that they are not legally allowed to regulate local building codes per state law.

Survey Findings

Over the past 20 years, natural and manmade disasters have increased in both frequency, severity and

cost. On average, 24 percent of counties have experienced at least one disaster in each of the last three

years. The past three hurricane and wildfire seasons have included six hurricanes that combined to cost

over $330 billion in damages and more than eight wildfires causing over $40 billion in damages.

i

These

disasters showcase the need for government officials, particularly county governments, to renew their

focus on their planning and response readiness activities. Consequently, the U.S. has learned the

importance of tactics and strategies that include scenario planning, land use planning, evacuation

planning, building code adoption and enforcement, internal and external communication planning,

citizen preparation, controlling information on social media, tracking volunteer hours and the impact of

disaster on goods movement and industry.

In order to remain healthy, vibrant, safe and economically competitive, America’s counties must be

engaged in all aspects and phases of emergency management: planning, preparedness, mitigation,

response and recovery. This report presents findings of current U.S. counties’ activities in these areas

from the Survey on Emergency Management in County Government.

Organizational Structure

The Survey on Emergency Management in County Government defined the emergency management

agency (EMA) as the department, division, organization or agency specifically tasked with Emergency

Management preparedness, response, recovery and mitigation plans and efforts. EMAs can be set up in

a variety of ways. They can be standalone or part of another county office, such as the sheriff’s office.

They can be made up of one volunteer employee or ten full-time paid staff members. Their structure is

typically reliant on county size and hazard vulnerability.

ii

Reporting Structure

Approximately 72 percent of survey respondents indicate that their chief emergency management

official reports directly to the county elected official(s), with just under half of chief emergency

management officials reporting directly to the county board (46 percent) and the other half (44 percent)

reporting directly to the county administrator, executive or manager. Less than 10 percent of chief

emergency management officials respond directly to the county sheriff, county public works director or

county health director, indicating a potential shift towards emergency management being a standalone

unit in the structure of county government. In small counties, chief emergency management officials are

twice as likely to report directly to elected official(s) than in large counties (82 to 46 percent,

respectively); in fact, in large counties, 31 percent of chief emergency management officials are

reported to be two steps removed from county elected official(s) – with their supervisor’s supervisor

being the individual to report directly to the county’s elected official(s). (See Tables 3 and 4.)

Staffing

The majority of survey respondents (88 percent) indicate that their county has a written board

ordinance or resolution that formally establishes an EMA, as shown in Table 1. On average, those county

EMAs employ 2.89 full time employees and 1.65 part time employees. EMA sizes are markedly different

across small, medium and large counties. On average, small county EMAs employ an average of 1.14 full

time and 1.41 part time employees, medium county EMAs employ 3.48 full time and 2.36 part time

employees, while large county EMAs employ 9.57 full time and 1.64 part time employees. See Table 2

for a full breakdown of county EMA employment.

Professional Development

A number of specialized training opportunities – from certifications to PhDs – conducted by the federal

government, state governments and private institutions exist for emergency managers. The Emergency

Management Institute (EMI) is the primary center for the development and delivery of emergency

management training in the United States.

iii

It is run by the Federal Emergency Management Agency

(FEMA) and emphasizes programs like the National Incident Management System (NIMS). NIMS is a

comprehensive, national approach to incident management that is applicable at all jurisdictional levels

and across functional disciplines. It is intended to be applicable across a full spectrum of potential

incidents, hazards, and impacts, regardless of size, location or complexity. Survey data suggest that 95

percent of counties formally endorse the National Incident Management System and over 90 percent of

county EMA employees have completed the NIMS training program (see Tables 5 and 6). Additionally,

over 15 percent have attended courses at the Emergency Management Institute (EMI), and 10 percent

have received a master’s degree in emergency and/or disaster management. Large county EMA

employees are as likely to have a master’s degree in emergency and/or disaster management as they

are to have attended courses at the FEMA EMI.

States, often through their state emergency management association, certify emergency managers at

several levels of certification. The survey data in Table 7 suggest that 78 percent of chief emergency

management officials have been certified as an emergency manager by their state. Notably, the

percentage of state certified emergency managers is approximately twice as much for small counties (84

percent) as it is for large counties (41 percent). National certification also exists through the

International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM). IAEM has two levels of certification, the

Certified Emergency Manager (CEM) and the Associate Emergency Manager (AEM). 8 percent of all chief

emergency management officials report that they have been certified by IAEM – with just under a

quarter (23 percent) of large county chief emergency management officials having achieved

certification.

Just as training levels vary among emergency managers, emergency management programs vary in

capability and distinction. In order to foster excellence and accountability in emergency management,

the Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP) created a voluntary, peer review

accreditation process in which EMAs are evaluated across 64 standards. 12 percent of respondents

indicate their county is accredited and compliant with all EMAP Emergency Management Standards, and

an additional 37 percent indicate that while they are not accredited, they make use of the standards

(see Table 8). Having a basic understanding of the EMAP standards can be helpful in building an

effective, well-rounded emergency management program.

Budget and Funding

iv

EMA departments primarily leverage local resources for annual operational support. While federal

resources are available, the use of these funds correlate to the size of counties and their capacity to

apply via complex application processes.

Local Funding Sources

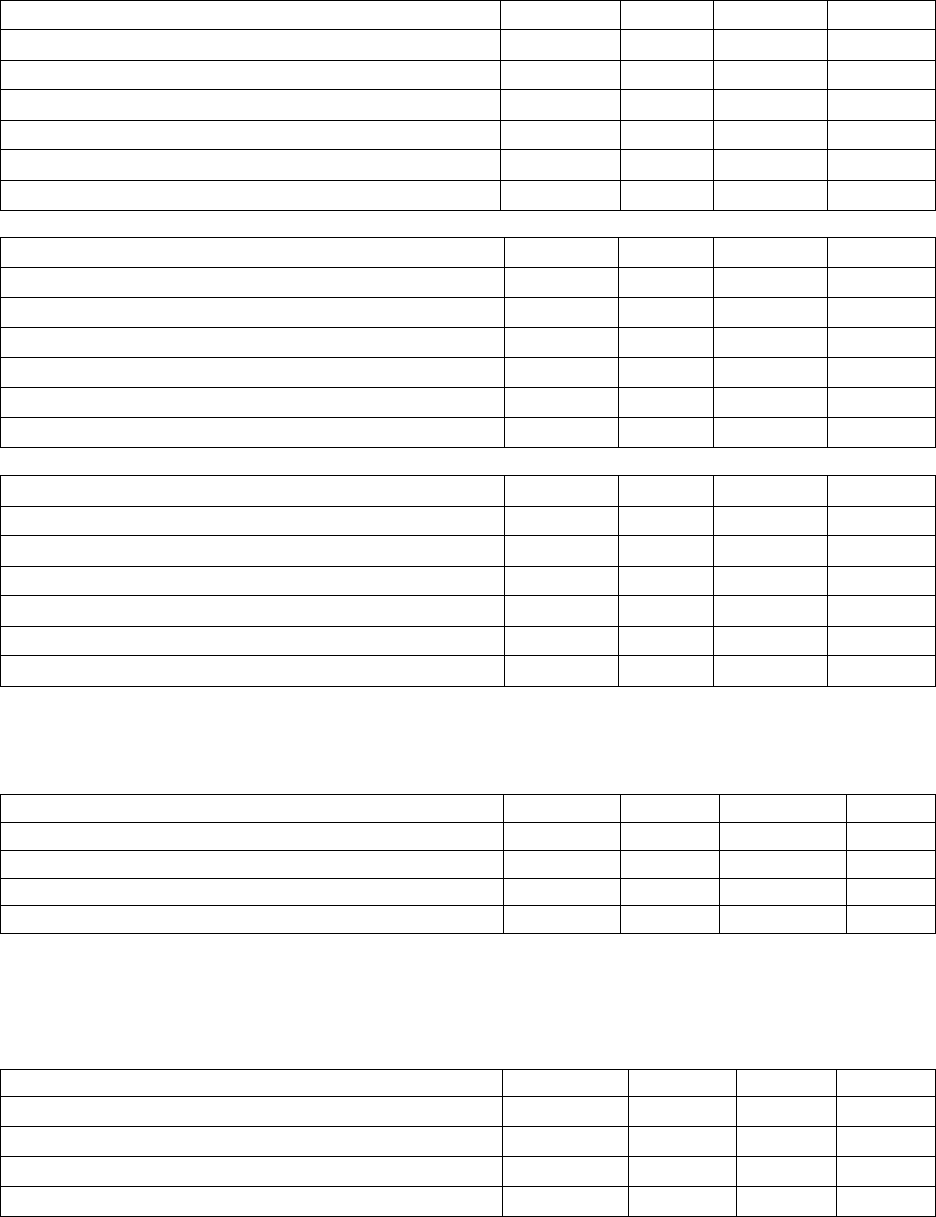

The EMA budget goes to fund activities in all phases of the emergency management cycle. As shown in

Tables 9 and 10, most counties dedicate 0 to 5 percent of the county’s total annual budget to the EMA

and manage the EMA budget within the county general fund (88 and 78 percent, respectively). Two-

thirds (67 percent) of survey respondents expect the county budget for the EMA to stay the same in the

next fiscal year, about a quarter (26 percent) anticipate a budget increase, while the remaining 7

percent expect their budget to decrease (see Table 11).

Ahead of a disaster, many counties (62 percent) adopt administrative and financial procedures that

allow the EMA to expediently request, apply for, receive, manage and expend funds during a local

emergency or disaster (see Table 12). Counties also maintain a variety of insurance coverages. The data

indicate that 43 percent of counties maintain private insurance, 41 percent participate in a statewide or

regional insurance pool, 20 percent self-insure via reserved funds and 49 percent maintain a “rainy day”

fund for emergencies and disasters (see Tables 13 and 14).

Federal Resources

Outside of county funding and insurance, counties also participate in a variety of federal grant programs.

Respondents indicate the top five federal grant programs that counties of all sizes participate in:

1. FEMA Emergency Management Performance Grant (EMPG) Program [82 percent]

2. FEMA Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP) [58 percent]

3. FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) [52 percent]

4. HUD Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program [39 percent]

5. FEMA Hazard Mitigation Planning Program [35 percent]

When looking at small, medium and large counties individually, these top five are generally the same

with some variation.

Large

Medium

Small

1. EMPG (96 percent)

1. EMPG (93 percent)

1. EMPG (75 percent)

2. HSGP (83 percent)

2. HSGP (67 percent)

2. HMGP (53 percent)

3. FEMA Urban Area Security

Initiative (UASI) Program (65

percent)

3. HMGP (50 percent)

3. HSGP (51 percent)

4. HMGP (61 percent)

4. FEMA Hazard Mitigation

Planning Program (32 percent)

4. FEMA Hazard Mitigation

Planning Program (39 percent)

5. PDM (48 percent)

4. FEMA Pre-Disaster Mitigation

(PDM) Grant Program (32

percent)

5. FEMA Pre-Disaster Mitigation

(PDM) Grant Program (23

percent)

These figures suggest that small counties are less likely to go after and/or receive federal funding, which

is in line with previous findings that rural communities often face barriers to competitive federal grants

due to lack of expertise and/or personnel dedicated to grant writing and management.

v

See Table 15 for

the full breakdown of county engagement with federal funding opportunities.

State & Other Sources

Beyond federal funding, counties primarily finance mitigation projects with state funding (35 percent)

and local taxes (34 percent). Very few counties finance mitigation projects through public-private

partnerships (9 percent) or with foundation funding (2 percent). Of note, 20 percent of respondents

indicated the use of “other” non-federal financing mechanisms. Some of the sources they indicate using

are general funds, in-kind funds, law enforcement forfeiture funds, stormwater and wastewater fees,

Local Emergency Planning Committee fees and grants, water management district grants and funds from

a nuclear plant decommissioning agreement. See Table 16 for complete data on non-federal funding.

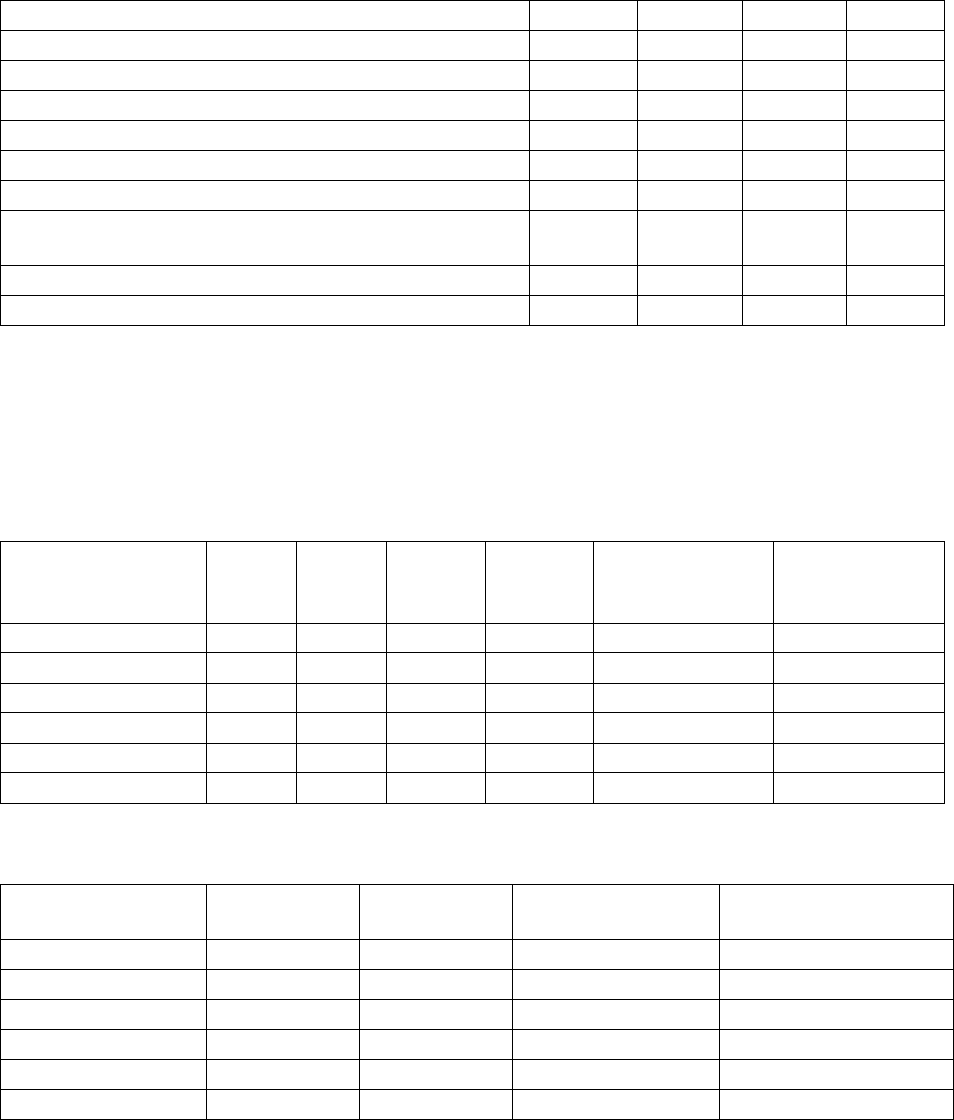

Partnerships

The survey asked people to indicate the agencies and organizations with whom they have worked over

the past five years, and in which phases they most often engaged and/or partnered with them. At each

level of government, counties indicated the top two phases in which they were most often engaged:

Federal

State

Regional

Local

Within county

Education and

training

Planning

Planning

Planning

Planning

Planning

Response

Education and

training

Response

Education and

training

The federal agencies that responding counties indicate engaging with most often, across all phases of

emergency management, are FEMA – primarily on recovery and education and training, and the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – primarily on education and training and

planning. The local governments and organizations counties engage with most often are schools,

municipalities, hospitals, other counties, faith-based organizations and the local business community –

and they engage with these local entities on planning more than three times as often as they do on

response. See Table 37 for the full scope of county partnerships.

Planning

99 percent of counties report having an Emergency Operations Plan (EOP) and Hazard Mitigation Plan

(HMP) in place. Of those counties, 69 percent report that the county EMA prepared the EOP, 13 percent

report that the EOP was prepared by a county multi-agency task force and 10 percent of EOPs were

prepared by a contractor (see Table 17). Additionally, 56 percent of counties report that they have

integrated their HMP into their county comprehensive plan (see Table 18). As hazard mitigation often

involves land use or other planning-related activities, this collaboration across departments helps to

promote consistency within and concurrency between plans while also increasing the probability of the

plan’s implementation.

vi

Coordination Across Plans

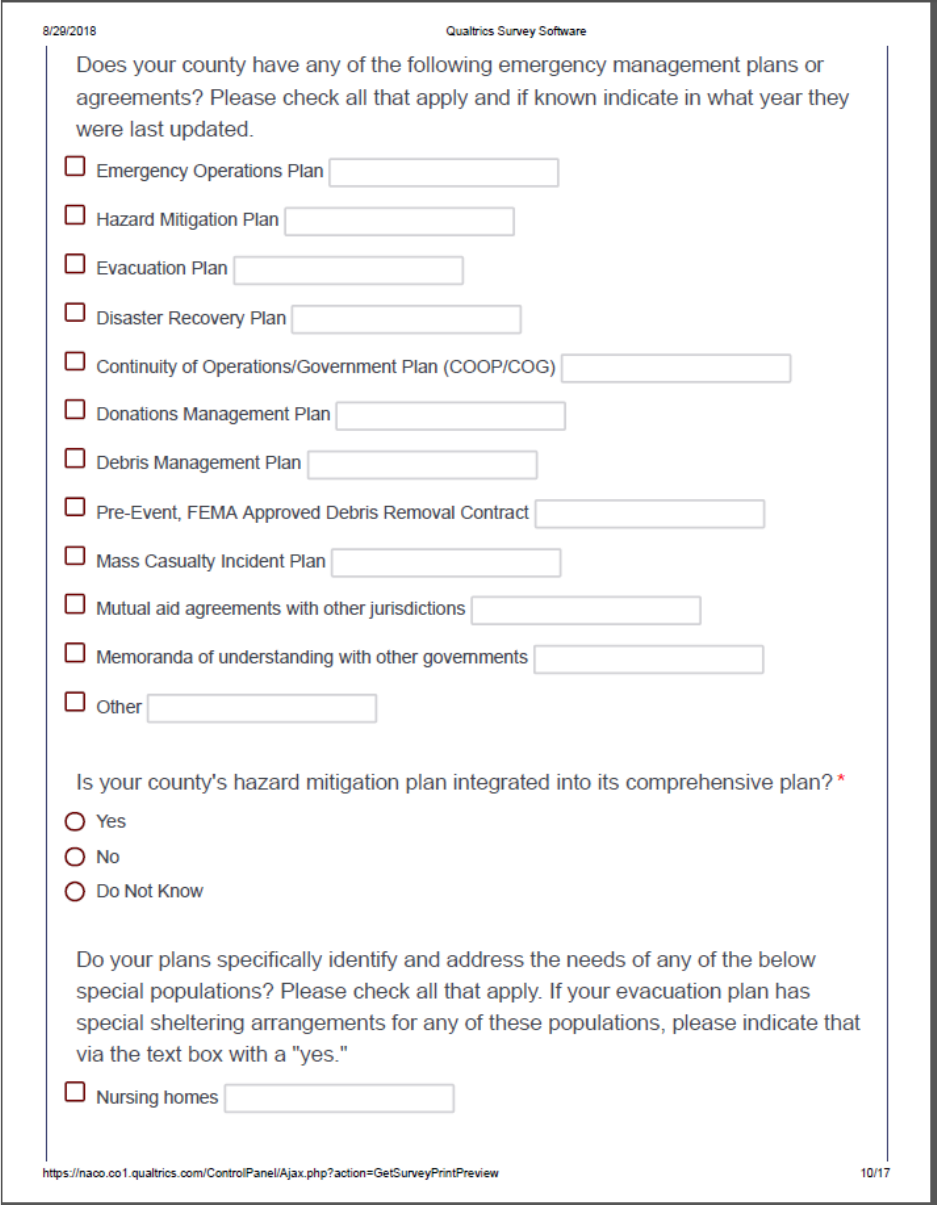

Looking beyond EOPs and HMPs, respondents indicate the top five plans and agreements counties have

in place:

1. Mutual aid agreements with other jurisdictions (78 percent)

2. Mass casualty incident plans (60 percent)

3. Continuity of operations/government plans—COOP/COG (58 percent)

4. Evacuation plans (57 percent)

5. Memoranda of understanding with other governments (56 percent)

These findings further suggest that counties understand the importance of and highly value planning

partnerships with surrounding counties and jurisdictions. When looking at small, medium and large

counties individually, this holds true as the plans and agreements they most often have in place are:

Large

Medium

Small

1. COOP/COG (95 percent)

1. Mutual aid agreements with

other jurisdictions (86 percent)

1. Mutual aid agreements with

other jurisdictions (73 percent)

2. Mutual aid agreements with

other jurisdictions (86 percent)

2. Mass casualty incident plan

(72 percent)

2. Evacuation plan (55 percent)

3. Debris management plan (82

percent)

3. Debris management plan (63

percent)

3. Mass casualty incident plans

(53 percent)

4. Mass casualty incident plans

(77 percent)

4. Evacuation plan (62 percent)

3. Memoranda of

understanding with other

governments (53 percent)

5. Memoranda of

understanding with other

governments (64 percent)

5. Memoranda of

understanding with other

governments (61 percent)

4. COOP/COG (53 percent)

Interestingly, the data in this table suggest small and medium counties are slightly more likely to have

evacuation plans in place than large counties (50 percent). The Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018

(DRRA) – which modified several FEMA programs to better assist state and local disaster mitigation,

preparedness and recovery – requires FEMA to develop and issue guidance regarding the identification

and maintenance of evacuation routes. This new requirement – as well as the evacuation issues

observed the past few disaster seasons – may impact county evacuation plans, both in content and

frequency of development and adoption.

Findings also suggest that large counties are likely to return to normal operations faster than small and

medium counties as they are one and a half to two times as likely to have a debris removal and

continuity of operations plan in place. Having a COOP plan indicates the county has pre-identified vital

departmental functions that must continue regardless of a disaster and has thought through the

execution of those functions to ensure minimal disruption to normal operations. See Table 19 for the full

breakdown of county emergency management planning efforts.

Special Populations

In planning, counties often account for the needs of special populations. Respondents suggest that the

special populations most often identified and addressed in county plans are:

1. Nursing home residents (85 percent)

2. Hospital patients (77 percent)

3. Pet owners (68 percent)

4. Non-English-speaking residents (41 percent)

5. Prisoners (38 percent)

These stay true across all government sizes, except 57 percent of large counties also plan for public

transit dependent populations. As FEMA continues its implementation of DRRA – which requires the

development of guidance regarding health care and long-term care facility prioritization and assistance

in the development of evacuation plans that account for the care and rescue of animals – it will be

interesting to see how often and in what capacity special populations are accounted for in county plans.

See Table 20 for further information on the inclusion of special populations in county planning efforts.

Use of Technology

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is an integral tool in today’s planning toolkit. Organizations use

GIS not only to map what is where but also consolidate data on those geographic points that can

provide situational awareness and information to support decision making, real-time and for planning

purpose. GIS enhance information sharing, communication and collaboration.

vii

Looking at county use of

GIS, 6 percent of counties indicate that they do not use GIS (see Table 21). Of those that do use GIS,

respondents indicate how their communities most often use GIS:

1. Accurate addressing

viii

(68 percent)

2. Dispatching response units (67 percent)

3. Mapping response resources (58 percent)

4. Identifying persons or facilities for notification of potential hazards (56 percent)

5. Identifying areas affected by an incident using meteorological information (52 percent)

6. Assessing risk (52 percent)

When looking at small, medium and large counties individually, the GIS is most often used for:

Large

Medium

Small

1. Mapping response resources

(86 percent)

1. Accurate addressing (76

percent)

1. Accurate addressing (64

percent)

Identifying persons or facilities

for notification of potential

hazards (86 percent)

2. Dispatching response units

(75 percent)

2. Dispatching response units

(63 percent)

3. Identifying areas affected by

an incident using

meteorological information (77

percent)

3. Mapping response resources

(70 percent)

3. Identifying persons or

facilities for notification of

potential hazards (52 percent)

Assessing risk (77 percent)

4. Identifying areas affected by

an incident using

methodological information (61

percent)

4. Mapping response resources

(49 percent)

Plan for critical infrastructure

(77 percent)

5. Identifying persons or

facilities for notification of

potential hazards (58 percent)

5. Assessing risk (47 percent)

Facilitate recovery (77

percent)

Plan for critical infrastructure

(58 percent)

6. Identifying areas affected by

an incident using

methodological information (45

percent)

Over half of county respondents indicate that their EMA works with an employee in the county planning

department or another central government unit to fulfill their GIS needs (see Table 22). Another quarter

have an in-house EMA employee perform their GIS work. Only 9 percent outsource to a private

contractor, and 5 percent work with their regional planning office.

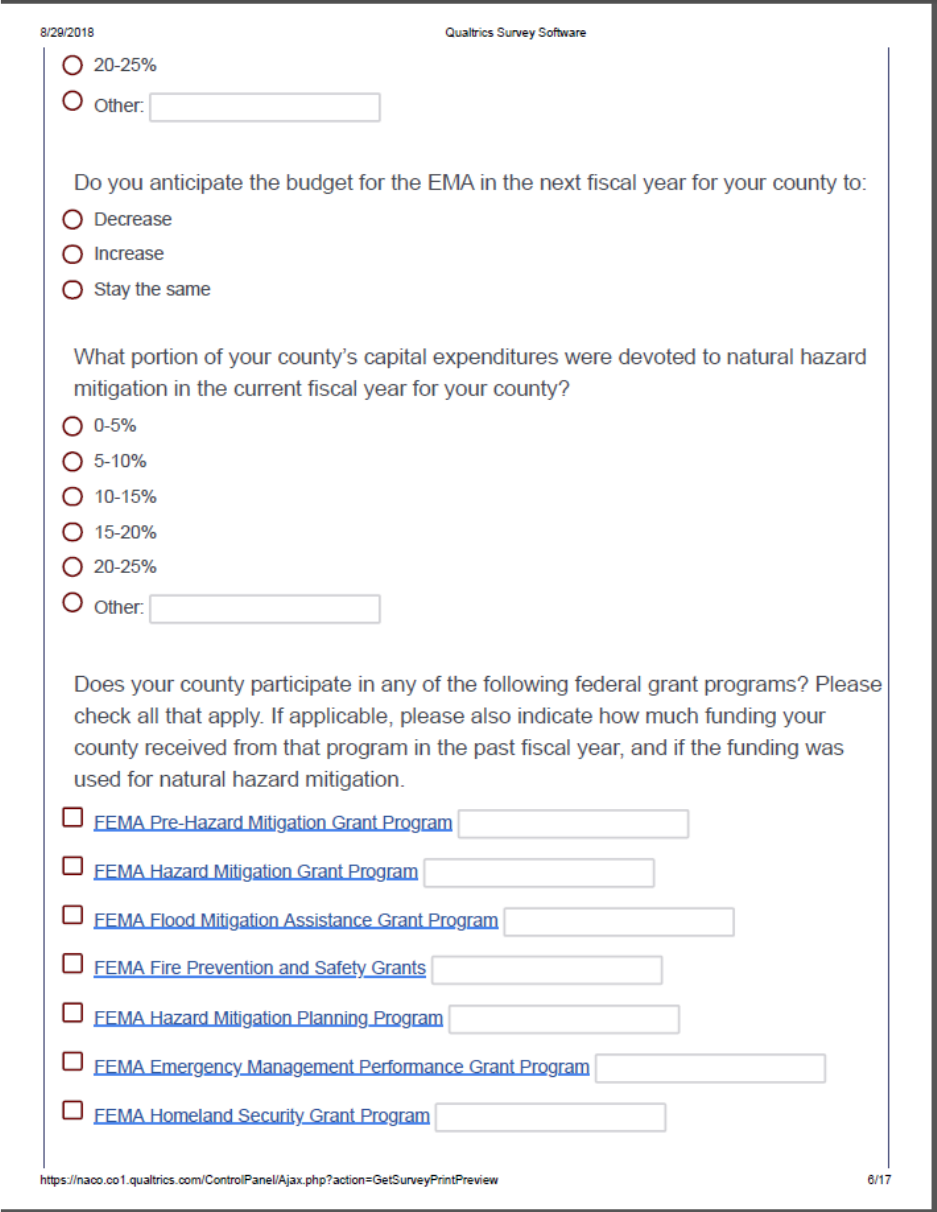

Preparedness

Before a disaster strikes, local governments must ensure that all stakeholders – from local elected

officials to the public – understand their risks to all hazards and are prepared for when they strike.

Counties employ various strategies to communicate risk and raise awareness of risk reduction strategies

to residents. Table 23 details the top four ways that responding counties – regardless of size –

communicate risk before a disaster:

1. Trainings or exercises (85 percent)

2. Public meetings (73 percent)

3. Social media (71 percent)

4. School visits (60 percent)

Beyond these top four strategies, large, medium and small counties communicate risk through:

Large Counties

(500,000 or more)

Medium Counties

(50,000-500,000)

Small Counties

(50,000 or less)

Civic engagement events (65

percent)

Civic engagement events (62

percent)

Newspaper or magazine ads (47

percent)

Radio or television spots (57

percent)

Radio or television spots (47

percent)

Civic engagement events (30

percent)

Newspaper or magazine ads (39

percent)

Newspaper or magazine ads (36

percent)

Radio or television spots (29

percent)

Additionally, 30 percent of large counties use direct mailers, compared to only 6 percent of medium and

small counties.

Exercises play a vital role in national preparedness by enabling whole community stakeholders to test

and validate plans and capabilities, and identify capability gaps and areas for improvement. While 85

percent of respondents identified trainings and exercises as the top means by which their county builds

disaster risk reduction awareness, only 64 percent have held a county-wide disaster preparedness drill

within the past year (see Tables 24 and 25). Looking within the last two years, that number rises to 81

percent. However, 19 percent of responding counties have not held a county-wide disaster

preparedness drill in over two years. When drills are held, the formats typically used are table top

exercises (63 percent), functional drills (48 percent) and full-scale simulations (46 percent). Drills,

regardless of format, are important means by which counties can test emergency plans and procedures.

They provide feedback on the process, promote interorganizational contact before a disaster strikes and

yield publicity that informs the public on the county’s planning and preparedness efforts.

ix

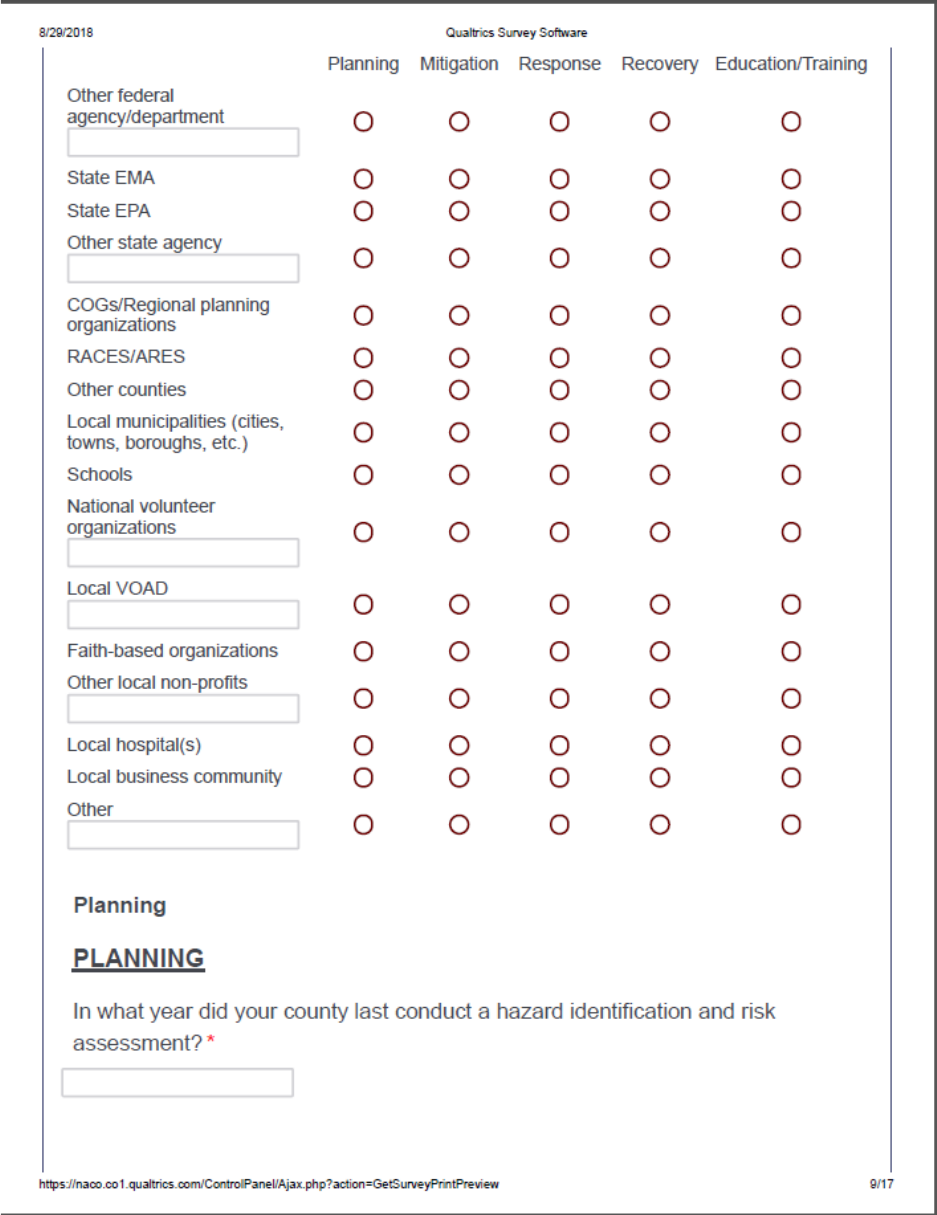

Preparedness Levels by County Agency and Community Groups

When asked to what extent agencies and community groups within their county are prepared for all

hazards, respondents indicated that most groups are prepared at a level two or three on a scale of zero

to four, with zero being not prepared at all and four being extremely prepared (see Table 26). The most

prepared groups are the local police departments, local fire departments and local hospitals and health

care providers. 68 percent of counties said their local police departments are prepared at a level three,

60 percent said their local fire departments are prepared at a level three and 55 percent said their local

hospitals and health care providers are prepared at a level three.

The least prepared groups are residents, the business community and early childhood development

centers – with over 25 percent of respondents indicating that these groups were only prepared at a level

one. Counties must ensure they have the necessary resources – food, water, vehicle, volunteers, etc. –

and facilities – shelters, recovery center, etc. – in place in the event of a disaster. The survey data

suggests that counties feel their various agencies and departments are generally prepared at a level

three (45 percent) or two (40 percent).

Digging deeper into the specifics of county preparedness efforts, 77 percent of respondents report their

counties have pre-designated shelters for disaster evacuees (see Table 27). Only 8 percent, however,

indicate that they have adequate housing stock to support temporary housing for residents, non-local

volunteers, federal employees, etc. (see Table 28). Temporary housing is necessary after a disaster to

help get residents on the way back to their homes and to restore emergency shelter facilities to their

original intended functions to help the community get back to its normal ready state.

Mitigation

With the FEMA 2022 Moonshots and DRRA, the topic of mitigation has once again risen to the top in the

resilience conversation. The FEMA 2022 Moonshots look to quadruple national investment in mitigation

and double the number of properties covered by insurance by 2022. The DRRA promises further

investments in mitigation and prevention efforts through several programs. Through both these

initiatives, the federal government is asking local governments to collaborate with them to achieve

these goals.

Some counties are already pursuing hazard mitigation strategies to build local disaster resilience.

Looking at local mitigation policies, the data in Table 29 suggests the top five mitigation policies adopted

by counties in the United States:

1. Building codes (56 percent)

2. Building setbacks (41 percent)

3. Overlay districts (41 percent)

4. Emergency vehicle access requirements (38 percent)

5. Buffer zones (26 percent)

While this ranking stays true for large, medium and small county governments, large and medium

counties are more likely to adopt mitigation policies than small counties. For example, 73 percent of

large and 70 percent of medium counties have adopted building code requirements while only 46

percent of small counties have done so. Of note, 22 percent of respondents indicate that they do not

regulate land use and 24 percent indicate that they do not regulate buildings codes. Correspondingly, 6

percent of counties report that they are not legally allowed to regulate local land use per state law and 8

percent report that they are not legally allowed to regulate local building codes per state law.

x

As part of

its changes to federal hazard mitigation policy, the DRRA emphasized the importance of the adoption

and enforcement of the latest published consensus-based codes, specifications and standards. These

changes include allowing the local government to engage FEMA during recovery to help the address

local building code and floodplain ordinance administration and enforcement post-disaster.

Beyond mitigation policy, 24 percent of large counties and 3 percent of all counties have established

non-FEMA funded repetitive flood loss property buyout programs, as shown in Table 30. Flood buyout,

or property acquisition, programs enable local governments to purchase eligible homes prone to

frequent flooding from willing, voluntary owners and return the land to open space, wetlands, rain

gardens or greenways.

xi

These programs reduce the number of flood-prone buildings and can decrease

the overall flood risk in the floodplain.

Additionally, as shown in Table 31, 53 percent of respondents indicate that their county participates in

the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Community Rating System (CRS). CRS is a voluntary

incentive program that recognizes communities for implementing floodplain management practices that

exceed the federal minimum requirements of the NFIP to provide protection from flooding. In exchange

for a community’s proactive efforts to reduce flood risk, policyholders can receive reduced flood

insurance premiums for buildings in the community.

xii

There are 10 CRS Classes. Class 1 requires the

most credit points and provides the largest flood insurance premium reduction (45 percent), while Class

10 means the community does not participate in the CRS, or has not earned the minimum required

credit points, and residents receive no premium reduction.

Response

A community’s initial response to a disaster can set the tone for its recovery. Open and proper

communications play a huge role in disaster response, both within county government, between county

government and its partners and from county government to the public. During response, EMAs are in

charge of implementing the Incident Command System (ICS) structure for field response and managing

the Emergency Operations Center (EOC).

xiii

The ICS enables coordinated, collaborative, effective and

efficient incident management by integrating a combination of facilities, equipment, personnel,

procedures and communications operating within a common organizational structure.

Concurrently, EOCs help counties to coordinate response activities by gathering decision makers

together in one location to supply them with the most current information.

xiv

An EOC can be physical or

virtual and can be dedicated solely to the EMA or used by multiple departments. The data in Table 32

suggests that 53 percent of counties have an EOC dedicated solely to the EMA; 43 percent of county

EMAs share the EOC with other departments; and 4 percent of counties have no EOC.

Beyond using an EOC to coordinate county communications internally, the top external means of

communications county respondents indicate using during emergencies are:

1. Emergency Alert Systems (90 percent)

2. Facebook (82 percent)

3. Landlines (71 percent)

4. Text messaging (70 percent)

5. Internet/email (62 percent)

When looking at small, medium and large counties individually, these hold true with slight variation,

although the levels of usage can vary quite substantially from large to small counties. See those

variations in Table 33.

Social Media

With the rise of social media over the past decade, EMA communications have transformed. EMAs now

use social media during a disaster to as an emergency management tool to conduct emergency

communications and issue warnings; receive victim requests for assistance; monitor user activities and

postings for situational awareness; identify and get in front of incorrect information and rumors; and

crowdsource information for flood water monitoring, damage assessments, etc. While 17 percent of

small counties indicate that they do not have any social media accounts, the majority of counties do

have social media accounts and employ staff to manage those accounts in a variety of ways during a

disaster (see Table 34). Many counties have a county employee who handles social media on a regular

basis (32 percent) and/or assign one employee to manage social media during a disaster as “other duties

as assigned” (25 percent). Very few counties engage social media volunteer teams during disaster (6

percent) and then only medium and small counties use this method. As for having an employee fully

committed to social media, large counties lead the way at 18 percent, medium counties closely follow at

13 percent and only 5 percent of small counties indicate having an employee fully committed to social

media. With regards to controlling misinformation during a disaster, 77 percent of counties closely

monitor social media to identify and get in front of rumors (see Table 35).

Other Communication Channels

Beyond social media, county EMAs use a variety of technology and software to help with information

management and communications. According to the survey data in Table 36, the top five technologies

and software most used by all sizes of county government – with slight variations in order – are:

1. WebEOC® (76 percent)

2. Interoperable communications equipment (71 percent)

3. Ham/shortwave radio (64 percent)

4. CAMEO (Computer-Aided Management of Emergency Operations)/ALOHA (49 percent)

5. Homeland Security Information Network (HSIN) (43 percent)

WebEOC® is a crisis management software that enhances an organization's preparedness, disaster

recovery and emergency management efforts.

xv

Interoperable communications equipment allows

county emergency responders to communicate and share voice and data information.

xvi

Ham and

shortwave radios are operated by members of the public and regulated by the Federal Communications

Commission (FCC).

xvii

During a disaster, licensed and trained ham radio operators – often members of

the Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES) or Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES) – help

provide both voice and data communications modes to bridge interoperability gaps between agencies.

CAMEO is a system of software applications used to plan for and respond to chemical emergencies;

ALOHA is a one of the software applications that estimates threat zones for chemical spills.

xviii

HSIN is a

network through which agencies can share sensitive but unclassified information, manage operations,

analyze data and send alerts and notices relevant to public safety.

xix

Conclusion

County governments generally feel well prepared in the event of a disaster. They are less confident,

however, in the preparedness of their residents and the non-governmental organizations within their

communities. To better prepare local communities, counties might increase their usage of no- or low-

cost pre-hazard mitigation strategies, their focus on social vulnerability – or the inability of a population

to withstand adverse impacts from disaster or other stressors – during the planning process and their

risk communications prior to a disaster. With the rise of social media – in general and as an emergency

communications strategy – counties have an ideal, no- to low- cost vehicle to share preparedness

messages.

Counties have done well to get their central emergency management plans in place: EOPs, HMPs,

mutual aid agreements, mass casualty incident plans and COOPs. They are accounting more often for

special populations with medical needs, but they could continue to increase their focus on other socially

vulnerable populations and housing concerns. Housing continues to be an issue – not only the lack of

affordable housing pre-disaster, but also the lack of temporary housing post-disaster.

Regarding the implementation of plans, funding for local projects is a major issue. Based on the survey

results, many counties may need a better understanding of what federal grant programs and non-

federal financing mechanisms are out there – especially for mitigation – and/or they may need

assistance in putting together more competitive applications.

xx

Overall, counties appear to be doing well in their planning for, preparedness for and response to

disasters. However, they could improve their mitigation planning, policies and implementation.

Methodology

NACo prepared the survey instrument with input from the Carl Vinson Institute of Government at the

University of Georgia and emergency management practitioners from local and federal emergency

management agencies. Requests with instructions for completing the survey went out in May to each of

the 3,069 U.S. counties. The requests were sent to county clerks, board presidents and emergency

management directors. Instructions requested that the clerk and/or board president send the request,

which was signed by NACo Resilient Counties Advisory Board Chair and Sonoma County Supervisor

James Gore, to the appropriate emergency management professional. NACo received completed

responses from 397 counties in May and June 2018, representing all Census divisions and 45 of the 50

states.

Acknowledgements

The National Association of Counties (NACo) would like to thank the Carl Vinson Institute of Government

at the University of Georgia for its historical insight into the original “Emergency Management in County

Government: A National Survey” that the school conducted in 2006 on behalf of NACo. Dr. Wes Clarke,

Senior Public Service Associate, provided valuable historical context for the 2006 survey and insight into

the original survey instrument’s development and analysis. Dr. Theresa Wright, Director of Survey

Research and Evaluation; Dr. John Barner, Survey Research and Evaluation Specialist; and Ms. Michelle

Bailey, Research Professional, assisted in brainstorming how to update the survey instrument for the

2018 survey respondent audience, taking into account changes in technology and survey respondent

behavior.

The survey instrument questions (see Appendix D) were improved greatly through the efforts of Mr.

Nick Crossley, Emergency Management Director for Hamilton County, Ohio; Mr. Judson Freed, CEM,

Emergency Management Director for Ramsey County, Minnesota; Ms. Margaret Larson, Emergency

Management Consultant for Ernst and Young; and representatives from the Federal Emergency

Management Agency. As experts in emergency and disaster management, they provided valuable

insights into aspects of the field and graciously reviewed multiple drafts of the survey instrument.

And, of course, a huge thank you to all the counties who took the time to complete the survey and share

their stories and practices. This report would have been impossible without the wealth of data they

shared. See Appendix C for the full list of participating counties.

This report was researched and written by Jenna Moran, associate program director for resilience, with

guidance from Jay Kairam, director of program strategy; Stacy Nakintu, research associate; Lindsey

Holman, associate legislative director for justice and public safety; and Shanna Williamson, NOAA Digital

Coast Fellow. The data for this report was analyzed by Stacy Nakintu, research associate, and Ricardo

Aguilar, data analyst.

About the National Association of Counties

The National Association of Counties (NACo) unites America’s 3,069 county governments. Founded in

1935, NACo brings county officials together to advocate with a collective voice on national policy,

exchange ideas and build new leadership skills, pursue transformational county solutions, enrich the

public’s understanding of county government and exercise exemplary leadership in public service. More

information at: www.naco.org.

About NACo’s Resilient Counties Initiative

Through the Resilient Counties initiative, NACo works with counties and their stakeholders to bolster

their ability to thrive amid changing physical, environmental, social and economic conditions.

Hurricanes, wildfires, economic collapse and other disasters can be natural or man-made, acute or long-

term, foreseeable or unpredictable. Preparation for and recovery from such events requires both long-

term planning and immediate action. Learn more about the initiative and its sponsors at:

https://www.naco.org/resources/signature-projects/resilient-counties-initiative.

Appendix A: Glossary

Associate Emergency Manager (AEM). The AEM designation is one of two types of certification offered

to emergency management professionals by IAEM.

Source: https://www.iaem.com/cem.

Building codes. Building codes govern the design, construction, alteration and maintenance of

structures by specifying minimum requirements to adequately safeguard the health, safety and welfare

of building occupants. Rather than create and maintain their own codes, many communities adopt the

model building codes maintained by the International Code Council (ICC).

Source: https://www.fema.gov/building-codes.

Building setbacks. Building setbacks can help keep development out of harm's way. Setback standards

establish minimum distances that structures must be positioned (or set back) from river channels and

coastal shorelines.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/setback.

Computer-Aided Management of Emergency Operations (CAMEO). CAMEO is a system of software

applications used to plan for and respond to chemical emergencies; ALOHA is a one of the software

applications that estimates threat zones for chemical spills.

Source: https://www.epa.gov/cameo

Certified Emergency Manager (CEM). The CEM designation is one of two types of certification offered

to emergency management professionals by IAEM.

Source: https://www.iaem.com/cem.

Comprehensive plans. A comprehensive plan sets the overall policy direction for a community’s future

development. It guides coordinated development and sets high standards of public services and facilities

in a county. They are important decision-making and priority-setting tools.

Source: https://projects.arlingtonva.us/plans-studies/comprehensive-plan/

Continuity of operations/government plans (COOP/COG). COOPs help to ensure the execution of

essential organizational functions and the fundamental duty of a department during all-hazards

emergencies or other situations that may disrupt normal operations. A COOP should: describe the

readiness and preparedness of the organization and its staff; outline to whom it should be distributed;

detail the process for activating and relocating (or not-relocating) personnel from the organization’s

primary facility to its continuity site(s); identify the continuation of essential functions – and delineate

responsibilities for key staff positions; identify critical communications and information technology (IT)

systems to support connectivity during crisis and disaster conditions; and specify how the organization

and its staff will return to normal operations. Ideally, a COOP also explains how it fits into other county

plans. They are helpful in managing scarce resources during disaster response and identifying vital

departmental functions that must continue regardless of a disaster.

Source: https://www.naco.org/resources/managing-disasters-county-level-focus-flooding-0

Debris management plans. A debris management plan is a written document that establishes

procedures and guidelines for managing disaster debris in a coordinated, environmentally-responsible

and cost-effective manner. The more local governments take a proactive approach to coordinating and

managing debris removal operations the better prepared they will be to restore public services and

ensure public health and safety in the aftermath of a disaster.

Source: https://emilms.fema.gov/IS0633/groups/8.html

Disaster preparedness exercises. Training and emergency exercises ensure that county personnel and

residents understand proper protocols and procedure. They prepare individuals to be ready to assist in

times of disaster and can be targeted to specific groups or for the public at-large.

Source: https://www.ready.gov/business/testing/exercises

Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 (DRRA). On October 5, President Trump signed H.R. 302, which

contains the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 (DRRA), on a 93-6 vote. DRRA modified several FEMA

programs to better assist state and local hazard mitigation, preparedness and recovery.

Source: www.naco.org/drra.

Emergency Alert Systems (EAS). The Emergency Alert System is a national public warning system that

requires TV and radio broadcasters, cable television systems, wireless cable systems, satellite digital

audio radio service providers, direct broadcast satellite service providers and wireline video service

providers to offer all levels of government the communications capability to address the American

public during a national emergency.

Source: https://www.fcc.gov/consumers/guides/emergency-alert-system-eas

Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP). Emergency Management Accreditation

Program (EMAP) is a voluntary, peer review accreditation process in which EMAs are evaluated across

64 standards.

Source: https://www.emap.org/

Emergency Operations Centers (EOC). EOCs help counties to coordinate response activities by gathering

decision makers together in one location to supply them with the most current information. An EOC can

be physical or virtual and can be dedicated solely to the EMA or used by multiple departments.

Source: https://www.ready.gov/business/implementation/incident

Emergency Operations Plan (EOP). In compliance with state laws, counties must develop emergency

operations plans (EOP) to address how they will deal with emergencies and disasters. An EOP specifies

the roles and responsibilities of county agencies and officials as well as state and federal agencies and

volunteer organizations. They can be contained within a comprehensive emergency management plan –

which also establishes a framework for mitigation, preparation, response and recovery.

Source: https://www.naco.org/resources/managing-disasters-county-level-focus-flooding-0

Geographic Information Systems (GIS). GIS is an integral tool in today’s planning toolkit. Organizations

use GIS not only to map what is where but also consolidate data on those geographic points that can

provide situational awareness and information to support decision making, real-time and for planning

purpose.

Source: https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/blog/mapping-future-gis/

Ham/shortwave radio. Ham and shortwave radios are operated by members of the public and regulated

by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). During a disaster, licensed and trained ham radio

operators – often members of the Amateur Radio Emergency Service (ARES) or Radio Amateur Civil

Emergency Service (RACES) – help provide both voice and data communications modes to bridge

interoperability gaps between agencies.

Source: https://www.domesticpreparedness.com/preparedness/ham-radio-in-emergency-operations/

Hazard Mitigation Plan (HMP). Hazard mitigation plans are documents that aim to identify, assess and

reduce the long-term risk to life and property from a range of natural hazards. They must be updated

every five years and can be stand-alone documents or integrated in a community’s local comprehensive

plan. Counties can prepare hazard mitigation plans on their own, with other jurisdictions within the

county or with other counties as part of a multi-county region. Counties must have FEMA approved

hazard mitigation plans in place to be eligible to receive federal funding for mitigation and other non-

emergency disaster projects.

Source: https://www.naco.org/resources/managing-disasters-county-level-focus-flooding-0

Homeland Security Information Network (HSIN). HSIN is a network through which agencies can share

sensitive but unclassified information, manage operations, analyze data and send alerts and notices

relevant to public safety.

Source: https://www.dhs.gov/homeland-security-information-network-hsin

HUD Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program. The CDBG program assists urban,

suburban and rural communities to improve housing and living conditions and expand economic

opportunities for low- and moderate-income persons. Counties use the flexibility of CDBG funds to

partner with the private and non-profit sectors to develop and upgrade local housing, water,

infrastructure and human services programs. There is also a separate Community Development Block

Grant Disaster Relief (CDBG-DR) program through which Congress allocates billions in funding to HUD

for necessary expenses related to natural disasters relief, long-term recovery, restoration of

infrastructure and housing and economic revitalization.

Sources: https://www.naco.org/resources/support-local-development-and-infrastructure-projects-

community-development-block-grant-1; https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/CDBG-

DR-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA is an agency of the United States Department

of Homeland Security focused on helping America – local governments, first responders, residents, etc. –

prepare for, prevent, respond to and recover from disasters.

Source: www.fema.gov/

FEMA 2022 Moonshots. The FEMA 2022 Moonshots look to quadruple national investment in mitigation

and double the number of properties covered by insurance by 2022.

Source: https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fio/Documents/FACIFebruary2018_FEMA.pdf

FEMA Emergency Management Institute (EMI). EMI is the primary center for the development and

delivery of emergency management training in the United States.

Source: https://training.fema.gov/

FEMA Emergency Management Performance Grant (EMPG) Program. EMPG provides resources to

assist state, local, tribal and territorial governments in preparing for all hazards. The EMPG program’s

allowable costs support efforts to build and sustain core capabilities across the Prevention, Protection,

Mitigation, Response and Recovery mission areas.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/emergency-management-performance-grant-program

FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP). HMPG funds help communities implement hazard

mitigation measures following a Presidential Major Disaster Declaration.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/hazard-mitigation-grant-program

FEMA Homeland Security Grant Program (HSGP). HSGP provides funding to states, territories, urban

areas and other local and tribal governments to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to and

recover from potential terrorist attacks and other hazards.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/homeland-security-grant-program

FEMA National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). NFIP aims to reduce the impact of flooding on private

and public structures by providing affordable insurance to property owners, renters and businesses.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program

FEMA National Flood Insurance Program Community Rating System (CRS). CRS is a voluntary incentive

program that recognizes communities for implementing floodplain management practices that exceed

the Federal minimum requirements of the NFIP to provide protection from flooding. In exchange for a

community’s proactive efforts to reduce flood risk, policyholders can receive reduced flood insurance

premiums for buildings in the community. There are 10 CRS Classes. Class 1 requires the most credit

points and provides the largest flood insurance premium reduction (45 percent), while Class 10 means

the community does not participate in the CRS, or has not earned the minimum required credit points,

and residents receive no premium reduction. Learn more on the CRS page on www.FloodSmart.gov.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program-community-rating-system

FEMA Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) Grant Program. The PDM Grant Program is designed to assist local

communities in implementing a sustained pre-disaster natural hazard mitigation program. The goal is to

reduce overall risk to future hazard events and reliance on federal funding in future disasters.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/pre-disaster-mitigation-grant-program

FEMA Urban Area Security Initiative (UASI) Program. Part of HSGP, the UASI Program intended to

provide financial assistance to address high-threat, high-density Urban Areas in efforts to build and

sustain the capabilities necessary to prevent, protect against, mitigate, respond to and recover from acts

of terrorism using the Whole Community approach.

Source: https://www.homelandsecuritygrants.info/GrantDetails.aspx?gid=17162

Flood buyouts. Flood buyout, or property acquisition, programs enable local governments to purchase

eligible homes prone to frequent flooding from willing, voluntary owners and return the land to open

space, wetlands, rain gardens or greenways.

Source: https://www.naco.org/resources/managing-disasters-county-level-focus-flooding-0

International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM). IAEM is the premier organization for

emergency management. It promotes the principles of emergency management to advance the

emergency management profession.

Source: www.iaem.com/

Incident Command System (ICS). The ICS is a flexible, standardized management system designed to

enable coordinated, collaborative, effective and efficient incident management by integrating a

combination of facilities, equipment, personnel, procedures and communications operating within a

common organizational structure.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/nimsfaqs.pdf

Interoperable communications equipment. Interoperable communications equipment allows county

emergency responders to communicate and share voice and data information

Source: http://www.disaster-resource.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=859&

Itemid=50

Mass-Casualty Incident (MCI) Plans. MCI plans are designed to provide guidance to assist emergency

response personnel in ensuring adequate and coordinated efforts to minimize loss of life, disabling

injuries, and human suffering by providing effective emergency medical assistance. They are usually an

annex within a larger county EOP.

Source: https://www.countyofnapa.org/DocumentCenter/View/1824/Multi-Casualty-Incident-

Management-Plan---Updated-June-2013-PDF

Memoranda of understanding (MOU) with other governments. MOUs are formal inter-local

agreements that define the roles and responsibilities of two governments during an emergency – or any

other event.

Source: https://emilms.fema.gov/is554/lesson4/01_04_030f1.htm

Mutual aid agreements with other jurisdictions. Mutual Aid Agreements are important mechanisms to

secure county operations in times of emergency because they can authorize assistance between two or

more neighboring counties, jurisdictions, and/or states – and also between private sector entities, NGOs

and other community partners. They put in place formalized systems that allow for expedited assistance

and acquisition of equipment and personnel in times of emergency. The primary difference between a

MOU and mutual aid agreement is an MOU can be used to pledge assistance without mutual benefits

while mutual aid agreements are reciprocal.

Source: https://www.naco.org/resources/managing-disasters-county-level-focus-flooding-0

National Incident Management System (NIMS). NIMS is a comprehensive, national approach to incident

management that is applicable at all jurisdictional levels and across functional disciplines. It is intended

to be applicable across a full spectrum of potential incidents, hazards, and impacts, regardless of size,

location or complexity.

Source: https://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/nimsfaqs.pdf

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NOAA is an agency within the United States

Department of Commerce that focuses on the conditions of the oceans, major waterways and the

atmosphere.

Source: www.noaa.gov/

Overlay districts. Overlay zoning is a regulatory tool that creates a special zoning district, over an

existing base zone(s), which identifies special provisions in addition to those in the underlying base zone.

Regulations or incentives are attached to the overlay district to guide development within a special area.

Within an overlay zone, common requirements may include building setbacks, density standards, lot

sizes, impervious surface reduction and vegetation requirements.

Source: https://www.uwsp.edu/cnr-ap/clue/Documents/PlanImplementation/Overlay_Zoning.pdf

Statewide or regional insurance pools. Similar to NFIP, statewide or regional insurance pools act as

insurers of last resort for property owners.

WebEOC®. WebEOC® is an incident management software that enhances an organization's

preparedness, disaster recovery and emergency management efforts.

Source: https://www.juvare.com/solutions/webeoc

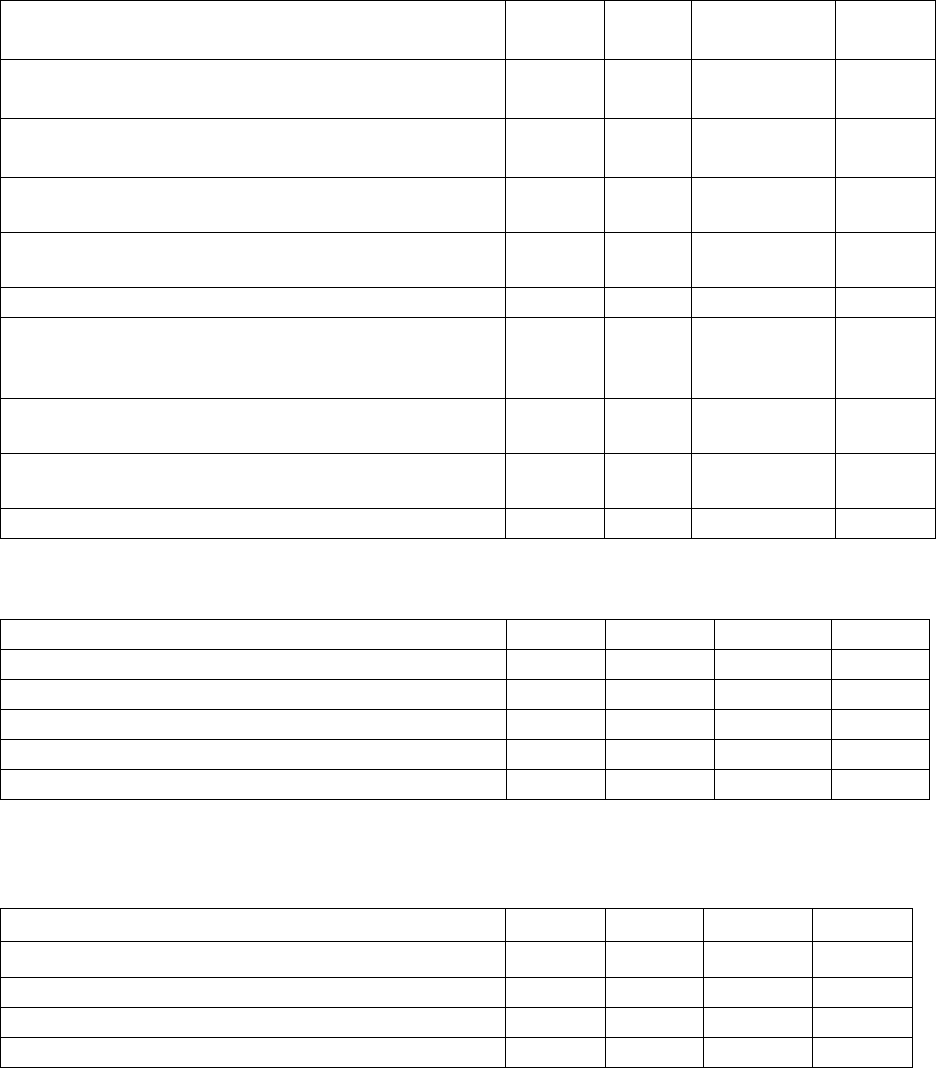

Appendix B: Data Tables

Table 1. Does your county have a written board ordinance or resolution formally establishing an

emergency management agency (EMA) and its responsibilities?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes

87.91%

86.94%

88.89%

92.31%

No

8.06%

7.76%

9.52%

3.85%

Do Not Know

4.03%

5.31%

1.59%

3.85%

Count

397

26

126

245

Table 2. How many individuals does the EMA employ?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Full Time Average

2.89

9.57

3.48

1.14

Full Time Standard Deviation

4.46

6.62

5.21

1.23

Part Time Average

1.65

1.64

2.36

1.41

Part Time Standard Deviation

2.36

0.84

4.11

1.39

Count

397

26

126

245

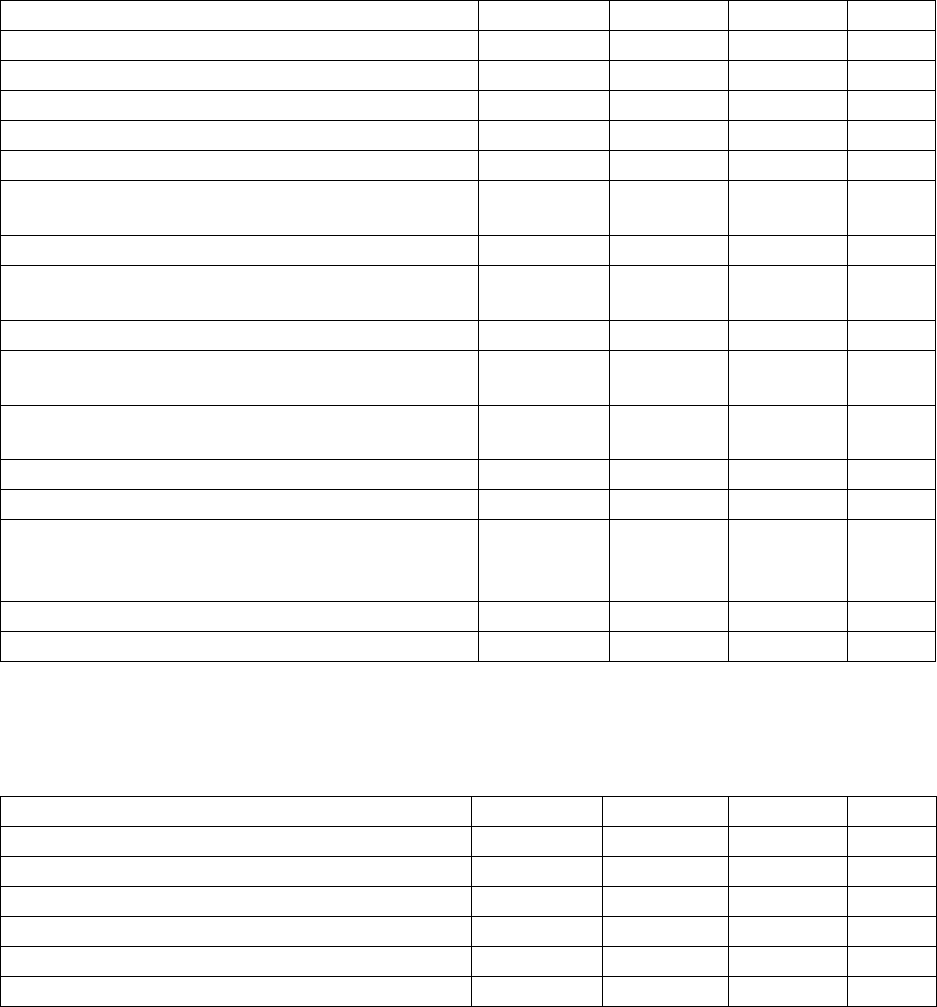

Table 3. How many reporting levels are there between the chief emergency management official and the

county elected official(s)?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

1 - reports directly to elected official(s) (e.g.

supervisor, commissioner, council member, borough

member, etc.)

71.79%

46.15%

56.35%

82.45%

2 - supervisor of the chief of emergency

management reports directly to elected official(s)

16.37%

19.23%

25.40%

11.43%

3 - supervisor's supervisor reports directly to elected

official(s)

7.05%

30.77%

11.90%

7.05%

Other

4.79%

3.85%

6.35%

4.79%

Count

397

26

126

245

Table 4. To whom does the chief emergency management official directly report? Please select all that

apply.

Total

Large

Medium

Small

County Board

45.59%

19.23%

30.16%

56.33%

County Administrator, Executive or Manager

43.83%

61.54%

53.97%

36.73%

County Sheriff

8.06%

7.69%

7.94%

10.61%

County Public Works Director or Engineer

0.76%

0.00%

3.17%

1.63%

County Health Director

2.02%

0.00%

0.79%

0.82%

Other

18.89%

34.62%

18.25%

17.55%

Count

397

26

126

245

Table 5. Please describe the education and training experience of the EMA. Please select all that apply.

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Completed the National Incident Management

System (NIMS) Training Program

93.04%

96.00

%

96.80%

90.76%

Attended some courses at the FEMA Emergency

Management Institute (EMI)

16.75%

24.00

%

15.20%

16.81%

Completed the Basic Academy at EMI

14.33%

36.36

%

12.38%

12.94%

Completed the Advanced Academy at EMI

9.02%

20.00

%

11.20%

6.72%

Completed the Executive Academy at EMI

4.12%

8.00%

4.80%

3.36%

Completed the Master’s Program at Naval

Postgraduate School Center for Homeland Defense

and Security (NPS CHDS)

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

Completed the Executive Leaders Program at NPS

CHDS

1.80%

4.00%

2.40%

1.26%

Master’s degree in emergency and/or disaster

management

9.79%

24.00

%

16.80%

4.62%

Count

388

25

125

238

Table 6. Does your county formally endorse the National Incident Management System?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes

94.84%

100.00%

98.15%

92.69%

No, but we do use the system.

3.15%

0.00%

0.93%

4.57%

No, and we do not use the system.

0.29%

0.00%

0.00%

0.46%

Do Not Know

1.72%

0.00%

0.93%

2.28%

Count

349

22

108

219

Table 7. Is your Chief Emergency Management Officer certified as an Emergency Manager by any of the

following?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Your State

78.05%

40.91%

75.24%

83.58%

International Association of Emergency Managers

7.62%

22.73%

12.38%

3.48%

Other

14.33%

36.36%

12.38%

12.94%

Count

328

22

105

201

Table 8. Is your county accredited by the Emergency Management Accreditation Program

(www.emap.org)?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes, we are accredited and compliant with all EMAP

Emergency Management Standards.

11.79%

36.00%

8.00%

11.23%

No, but we make use of EMAP Emergency

Management Standards

37.44%

48.00%

47.20%

31.25%

No, and we do not make use of EMAP Emergency

Management Standards.

34.10%

16.00%

38.40%

33.75%

Do Not Know

16.67%

0.00%

6.40%

23.75%

Count

390

25

125

240

Table 9. What percentage of the county's total annual budget is dedicated to the EMA?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

0-5%

87.53%

86.96%

93.81%

84.55%

5-10%

6.23%

0.00%

3.54%

8.15%

10-15%

0.54%

0.00%

0.00%

0.86%

15-20%

0.27%

0.00%

0.00%

0.43%

20-25%

0.27%

4.35%

0.00%

0.00%

Other

5.15%

8.70%

2.65%

6.01%

Count

369

23

113

233

Table 10. The budget for the EMA is located in the:

Total

Large

Medium

Small

General Fund

78.14%

95.65%

78.76%

76.09%

Separate governmental fund

13.93%

0.00%

12.39%

16.09%

Other

7.92%

4.35%

8.85%

7.83%

Count

366

23

113

230

Table 11. Do you anticipate the budget for the EMA in the next fiscal year for your county to decrease,

stay the same or increase?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Decrease

7.07%

13.04%

3.54%

8.19%

Stay the Same

66.85%

69.57%

61.95%

68.97%

Increase

26.09%

17.39%

34.51%

22.84%

Count

368

23

113

232

Table 12. Pre-disaster, has your county adopted -- or during a disaster declaration, does your state

automatically implement -- administrative and fiscal procedures that allow the EMA to expediently

request, apply for, receive, manage and expend funds during a local emergency or disaster event?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes

61.81%

81.82%

73.21%

54.35%

No

22.25%

9.09%

19.64%

24.78%

Do Not Know

13.19%

4.55%

4.46%

18.26%

Other

2.75%

4.55%

2.68%

2.61%

Count

364

22

112

230

Table 13. Does your county maintain insurance against disaster damage for its buildings and

infrastructure? Please select all that apply.

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes, it maintains private insurance coverage

43.14%

14.29%

41.67%

46.61%

Yes, it is part of a statewide/regional insurance

pool.

41.43%

14.29%

35.19%

47.06%

Yes, it self-insures using reserved funds.

19.71%

80.95%

34.26%

6.79%

No, it has no disaster insurance

3.43%

4.76%

0.93%

4.52%

Count

350

21

108

221

Table 14. Does your county maintain a "rainy day" reserve fund to pay for emergencies and disasters?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes

48.78%

56.72%

52.21%

46.35%

No

30.89%

30.43%

27.43%

32.62%

Do Not Know

20.33%

13.04%

20.35%

21.03%

Count

369

23

113

233

Table 15. Does your county participate in any of the following federal grant programs? Please select all

that apply.

Total

Large

Medium

Small

FEMA Pre-Hazard Mitigation Grant Program

27.62%

47.83%

32.43%

22.86%

FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program

52.33%

60.87%

49.55%

52.86%

FEMA Flood Mitigation Assistance Grant Program

15.12%

30.43%

18.02%

11.90%

FEMA Fire Prevention and Safety Grants

20.64%

17.39%

26.13%

18.10%

FEMA Hazard Mitigation Planning Program

35.47%

21.74%

32.43%

38.57%

FEMA Emergency Management Performance

Grant Program

81.98%

95.65%

92.79%

74.76%

FEMA Homeland Security Grant Program

58.43%

82.61%

66.67%

51.43%

FEMA Radiological Emergency Preparedness

Program

11.92%

21.74%

15.32%

9.05%

FEMA Urban Area Security Initiative Program

8.72%

65.22%

9.91%

1.90%

HUD Community Development Block Grant

Program

39.13%

16.22%

10.95%

14.53%

HUD Community Development Block

Grant−Disaster Recovery Program

6.10%

13.04%

10.81%

2.86%

USDA Emergency Watershed Protection Program

4.65%

8.70%

4.50%

4.29%

NOAA Coastal Resilience Grant Program

2.62%

4.35%

2.70%

2.38%

CDC Hospital Preparedness Program - Public

Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative

Agreement

10.76%

26.09%

14.41%

7.14%

Other

8.14%

8.70%

8.11%

8.10%

Count

331

23

110

198

Table 16. What non-federal financing mechanisms have you used to fund mitigation projects?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

State funding

34.83%

11.11%

31.67%

37.88%

Local tax funding

34.33%

33.33%

35.00%

34.09%

Foundation funding

1.99%

11.11%

3.33%

0.76%

Public private partnerships

8.46%

11.11%

13.33%

6.06%

Other

20.40%

33.33%

16.67%

21.21%

Count

201

9

60

132

Table 17. Who prepared the emergency operations plan?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

County EMA

68.97%

63.64%

71.56%

68.20%

County multi-agency task force

13.22%

22.73%

16.51%

10.60%

Regional planning organization

4.02%

0.00%

0.00%

6.45%

Contractor

9.48%

9.09%

9.17%

9.68%

Other

4.31%

0.00%

0.00%

6.45%

Count

348

22

109

217

Table 18. Is your county's hazard mitigation plan integrated into its comprehensive plan?

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Yes

55.68%

47.83%

57.27%

55.71%

No

27.84%

39.13%

30.91%

25.11%

Do Not Know

16.48%

13.04%

11.82%

19.18%

Count

352

23

110

219

Table 19. Does your county have any of the following emergency management plans or agreements?

Please select all that apply.

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Emergency Operations Plan

99.43%

100.00%

100.00%

99.08%

Hazard Mitigation Plan

98.84%

100.00%

94.50%

94.50%

Evacuation Plan

57.02%

50.00%

62.39%

55.05%

Disaster Recovery Plan

44.13%

59.09%

48.62%

40.37%

Continuity of Operations/Government Plan

57.59%

95.45%

59.63%

52.75%

Donations Management Plan

28.94%

59.09%

38.53%

21.10%

Debris Management Plan

52.72%

81.82%

63.30%

44.50%

Pre-Event, FEMA Approved Debris Removal

Contract

14.61%

31.82%

26.61%

6.88%

Mass Casualty Incident Plan

60.46%

77.27%

71.56%

53.21%

Mutual aid agreements with other jurisdictions

77.94%

86.36%

86.24%

72.94%

Memoranda of understanding with other

governments

56.45%

63.64%

61.47%

53.21%

Other

5.16%

0.00%

9.17%

3.67%

Count

349

22

109

218

Table 20. Do your plans specifically identify and address the needs of any of the below special

populations? Please select all that apply.

Total

Large

Medium

Small

Nursing homes

85.48%

85.71%

82.83%

86.89%

Hospitals

76.90%

90.48%

83.84%

71.58%

Homeless

21.78%

38.10%

26.26%

17.49%

Non-English speaking

40.90%

90.48%

48.48%

30.60%

Public transit dependent

24.09%

57.14%

34.34%

14.75%

Pet owners

68.32%

90.48%

77.78%

60.66%

Prisoners

37.95%

47.62%

41.41%

34.97%

Sex offenders

12.21%

19.05%

17.17%

8.74%

Other

5.28%

4.76%

6.06%

4.92%

Count

303

21

99

183