Frontiers in Psychology 01 frontiersin.org

Enhancing English reading skills

and self-regulated learning

through online collaborative

flipped classroom: a comparative

study

YingWang *

Department of Foreign Language, Liaocheng University Dongchang College, Liaocheng, Shandong,

China

Introduction: This research investigates the eectiveness of an online

collaborative flipped classroom approach in enhancing English reading skills and

self-regulated learning among Chinese English learners.

Methods: A total of 71 participants were divided into three instructional groups:

traditional instruction (TI) group (n = 24), flipped instruction (FI) group (n = 22),

and online flipped instruction (OFI) group (n = 25). The participants’ reading

comprehension ability was assessed using the reading section of the IELTS exam.

Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) strategy use was evaluated using a questionnaire,

and weekly online quizzes assessed participants’ understanding of course

materials. Online learning behaviors were examined by considering online log-on

times. The instruction period lasted for 12 weeks, with pre-tests and post-tests

conducted to measure progress.

Results: The results indicated that both the FI and OFI groups outperformed the TI

group in terms of reading comprehension and self-regulated learning. Furthermore,

the OFI students demonstrated superior online learning behaviors and objective

performances compared to the FI students.

Discussion: These findings suggest that the integration of flipped and online

instruction methods holds promise for improving English reading skills and

enhancing self-regulated learning among Chinese English learners.

KEYWORDS

online collaborative flipped classroom, English reading skills, self-regulated learning,

online learning behaviors, EFL students

Introduction

Online learning has emerged as an adaptable, accessible, and ecient avenue for second

language (L2) acquisition, enabling learners to assume an active role in their language learning

journey (Lin etal., 2017; Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020; Subedi etal., 2020; Pokhrel and Chhetri,

2021). In fact, the surge of online learning and digitalized education has sparked a transformative

shi in the educational landscape, ushering in an era of digital transformation within this

domain (Fisher, 2006; García-Morales etal., 2021; Zaris and Ehymiou, 2022; Fathi etal., 2023;

Widayanti and Meria, 2023). Amidst this evolving educational paradigm, a prominent innovative

strategy has garnered widespread recognition for its student-centered ethos–the ipped

OPEN ACCESS

EDITED BY

Mohammed Saqr,

University of Eastern Finland, Finland

REVIEWED BY

Alex Zarifis,

Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, France

Natanael Karjanto,

Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea

Diana Akhmedjanova,

National Research University Higher School of

Economics, Russia

*CORRESPONDENCE

Ying Wang

RECEIVED 08 July 2023

ACCEPTED 27 September 2023

PUBLISHED 16 October 2023

CITATION

Wang Y (2023) Enhancing English reading skills

and self-regulated learning through online

collaborative flipped classroom: a comparative

study.

Front. Psychol. 14:1255389.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

COPYRIGHT

© 2023 Wang. This is an open-access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The

use, distribution or reproduction in other

forums is permitted, provided the original

author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are

credited and that the original publication in this

journal is cited, in accordance with accepted

academic practice. No use, distribution or

reproduction is permitted which does not

comply with these terms.

TYPE Original Research

PUBLISHED 16 October 2023

DOI 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 02 frontiersin.org

classroom. is approach integrates various pedagogical elements,

encompassing cooperative and collaborative learning, peer-based

interactions, problem-solving techniques, and dynamic learning

methods, eectively craing an engaging online learning milieu

(Slavin, 1991; Topping and Ehly, 1998; Michael, 2006; Bergmann and

Sams, 2014; Hung, 2017; Fathi etal., 2021). rough this multifaceted

approach, the ipped classroom leverages technology to optimize

learning experiences and elevate learner engagement.

Flipped classrooms, a pedagogical approach gaining prominence

in the eld of English as a foreign language (EFL) instruction, are

characterized by a fundamental shi in the traditional classroom

paradigm. In the EFL context, a ipped classroom model involves the

strategic use of digital resources to invert the conventional sequence

of in-class instruction and out-of-class learning activities. is

instructional approach redenes the roles of both educators and

learners, fostering a more learner-centered and interactive

environment. In a typical ipped EFL classroom, educators curate and

deliver digital content, oen in the form of video lessons, online

modules, or multimedia materials, which cover core course topics and

language skills. Students are provided access to these resources prior

to in-person class sessions (Chen Hsieh etal., 2017). is pre-class

exposure to content equips learners with foundational knowledge,

enabling them to arrive at in-class sessions prepared and ready for

interactive engagement. During in-person class time, the focus shis

from traditional lecturing to collaborative and application-based

activities. Educators facilitate discussions, problem-solving exercises,

and hands-on language tasks that encourage active participation and

deeper comprehension. is approach capitalizes on the concept of

“homework in the classroom” and “classwork at home, “allowing

students to clarify doubts, seek clarication, and engage in peer-to-

peer learning under the guidance of their instructors (Mehring, 2016).

While the ipped classroom has been recognized as a benecial

approach for enhancing EFL learners’ linguistic competence

(O’Flaherty and Phillips, 2015; Shih and Huang, 2020; Turan and

Akdag-Cimen, 2020), limited research exists on its impact on other

variables, particularly reading comprehension–an essential skill for

academic knowledge acquisition–and self-regulated learning

strategies–an important tool for independent language learning (Vitta

and Al-Hoorie, 2020; Fathi and Rahimi, 2022). Research suggests

that an online ipped classroom model can enhance reading

comprehension (Karimi and Hamzavi, 2017; Samiei and Ebadi, 2021).

Reading comprehension involves constructing meaning by connecting

background knowledge with textual information, making it a vital

component of academic contexts (Yapp etal., 2021). Learners need to

develop the ability to read independently, even in online or home

settings, by engaging with texts at the word, sentence, and text levels,

seeking feedback from peers through discussions, accessing resources,

and reecting on their reading practices (Jeon and Yamashita, 2014).

Flipped classrooms, a pedagogical innovation gaining traction,

oen leverage homework assignments focused on reading materials

to cultivate learners’ autonomy, motivation, and a positive attitude

toward advancing reading comprehension skills (Fulgueras and

Bautista, 2020). Additionally, an intrinsic link exists between the

ipped classroom model and the cultivation of self-regulated learning

(SRL) strategies. Within this paradigm, learners are entrusted with the

responsibility of not only acquiring and organizing information but

also actively engaging in processes such as monitoring, reection, and

evaluation of their own learning practices (Lai and Hwang, 2016;

eobald, 2021). Crucially, ipped EFL classrooms prioritize the

learner’s autonomy and self-regulated learning. Learners are

encouraged to take ownership of their learning process, make

informed decisions regarding their study pace, and employ self-

regulation strategies to enhance their language acquisition process

(Lai and Hwang, 2016). is instructional method harnesses

technology to create a dynamic and adaptable learning ecosystem that

empowers students to assume agency over their language learning.

e inclusion of self-regulated learning as a variable of interest

alongside reading comprehension is guided by the understanding that

these two aspects might beintertwined in a symbiotic relationship.

Self-regulated learning encompasses a spectrum of behaviors,

motivations, and metacognitive functions, all of which converge as

students plan learning tasks, set attainable goals, track their progress,

and engage in thoughtful reection on their learning journey (Nilson,

2023). e strategic employment of self-regulated learning strategies,

especially within the context of online collaborative ipped

classrooms, is postulated to synergistically enhance reading

comprehension abilities. is study endeavors to unravel the interplay

between self-regulated learning and reading comprehension, shedding

light on how the deliberate cultivation of metacognitive strategies

through the ipped classroom model can potentially inuence

learners’ abilities to comprehend and engage with English text.

Despite separate investigations on the ipped classroom, reading

comprehension, and self-regulated learning strategies, further

research is needed to understand how online ipped classrooms can

inuence reading comprehension and self-regulated strategies. To ll

this research gap, this study aims to compare the eects of online

ipped instruction and traditional ipped instruction on L2 reading

comprehension and self-regulated learning among Chinese EFL

learners. Additionally, the study seeks to explore dierences in online

learning behaviors between the two instructional groups. By saturating

and conrming the existing literature and generating context-based

ndings, this study contributes to the expanding body of research on

the eectiveness of the ipped classroom model in L2 instruction.

Moreover, it provides valuable insights into the impact of ipped

instruction on self-regulated learning in an online setting. e

ndings of this study may have practical implications for language

teachers and curriculum developers interested in incorporating the

ipped classroom model into their language instruction.

Literature review

Flipped classroom

e numerous contributions of digital learning to motivate

students and make students active language learners were due to its

approachability, convenience, collaboration, and proximity of digital

devices that could enhance autonomy and add variations to the

learning process (Prensky, 2005; Murdock and Williams, 2011; Zaris

and Ehymiou, 2022). e same was advocated in Asian countries

since students widely used technological features to communicate

through text, video calls, and other features that could help them

interact and engage (Sweeny, 2010). Enhancing student-centered

approaches in the online environment, teachers can employ ipped

classroom model (FCM) to change traditional class activities. FCM

brings rich chances for learners, adds exibility and adaptability

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 03 frontiersin.org

(Bergmann and Sams, 2014; Shih and Huang, 2020), and oers

practical tasks during class. Insights have arisen from diverse elds,

spanning social sciences (Wanner and Palmer, 2015; Lee and Wallace,

2018), engineering (Karabulut-Ilgu et al., 2018), and education

(Zainuddin and Attaran, 2016; Sommer and Ritzhaupt, 2018), all of

which increasingly advocate the eectiveness of the ipped classroom

in enhancing learners’ educational outcomes (Çakıroğlu and Öztürk,

2017; Liu etal., 2019). Furthermore, several dening characteristics

have been proposed for the ipped classroom, including interactive

learning (Crouch etal., 2007), real-time engagement (Novak, 2011),

inverted instruction (Davis, 2013), and the ipped learning model

(Bergmann and Sams, 2014).

Participating in online ipped classrooms might empower EFL

learners to cultivate autonomy in their decision-making and actions,

fostering a sense of ownership and control over their reading

experiences (Mehring, 2016; Fulgueras and Bautista, 2020). is

newfound autonomy motivates learners to proactively adapt and

rene their reading strategies to meet the demands of comprehension.

Moreover, learners develop a positive attitude toward the challenges

encountered during the reading process, embracing them as

opportunities for growth and deeper understanding (Jia etal., 2023).

Furthermore, online ipped classrooms oer EFL learners avenues for

improving their vocabulary and grammatical knowledge (Turan and

Akdag-Cimen, 2020). Prior to, during, or aer reading a text, learners

can leverage various techniques to enhance their language prociency

(Jiang etal., 2022). ese include consulting dictionaries to clarify

unfamiliar words, utilizing contextual clues to predict and deduce

meanings, engaging in discussions with peers to elicit insights, and

employing eective organizational strategies such as rehearsal,

rereading, and summarization (Mohammaddokht and Fathi, 2022).

By employing a range of cognitive and metacognitive strategies,

learners optimize their reading experience and foster a deeper

understanding of the text (Kintsch, 2012; Fischer and Yang, 2022).

rough the interactive and collaborative nature of online ipped

classrooms, EFL learners engage in a multifaceted approach to

reading. ey not only improve their linguistic competencies but also

develop critical thinking skills, cultivate eective study habits, and

foster a reective stance toward their reading practices (Fulgueras and

Bautista, 2020; Samiei and Ebadi, 2021). is comprehensive approach

to reading instruction nurtures learners’ condence, self-ecacy, and

motivation, positioning them for success in their language

learning journey.

e ipped classroom can indirectly use technology, mobile, and

computers outside of the classroom by watching videos of lectures,

working with multimedia with other peers to gain knowledge and

information (Kiernan and Aizawa, 2004; Stockwell, 2013; Amer,

2014), and have more considerable engagement in problem-solving,

knowledge-sharing, and information-exchange communicative

activities which are meaningful, along with personalized feedback in

the classroom (Kim etal., 2017; Zarrinabadi and Ebrahimi, 2018). e

benets of experiencing ipped classroom can bepositive perceptions

of being actively involved, having more engagement, enhancing

autonomy and critical thinking (Critz and Knight, 2013), and reaching

greater achievement (Butt, 2014). e empirical ndings also add

novel ndings to the literature. Accordingly, aer investigating 66

pre-service English language teachers, Gok etal. (2021) found that

there could bea considerable decline in FL classroom anxiety and

reading anxiety during the ipped classroom. In another study, Jiang

etal. (2021) revealed that learners’ demeanor and others’ assistance

could moderate the signicance of preparation to bemotivated and

involved in an online ipped classroom.

Numerous investigations have explored the inuence of ipped

classroom methodologies on the reading prociencies of EFL students

and associated variables. In their study, Mohammaddokht and Fathi

(2022) noted that ipped instruction produced substantial

enhancements in EFL reading capabilities while concurrently

alleviating reading-related apprehension. ese ndings imply the

potential utility of ipped instruction in the context of EFL reading

courses. Correspondingly, Fulgueras and Bautista (2020) scrutinized

the repercussions of ipped classrooms on the development of critical

thinking abilities and reading comprehension among senior high

school ESL learners in the Philippines. e outcomes indicated

advancements in critical thinking and reading comprehension

prociencies for both the ipped and conventional lecture-discussion

pedagogies. However, the ipped learning approach unequivocally

outperformed its traditional counterpart, underscoring its

eectiveness in fortifying these competencies.

Examining student viewpoints on the implementation of ipped

classrooms in EFL reading classes during the Covid-19 pandemic,

Nursyahdiyah etal. (2022) conducted a case study that unveiled the

ecacy of the ipped classroom strategy in enhancing the caliber of

EFL learning. Furthermore, it fostered greater autonomy among

students in their learning endeavors and positively inuenced the role

of technology in the realm of education. Yulian’s research (2021)

established that the adoption of the ipped classroom paradigm led to

enhancements in critical thinking skills pertinent to critical reading.

Students expressed favorable perceptions of this approach, placing

emphasis on self-guided learning as a principal advantage. Likewise,

Maharsi et al. (2021) scrutinized the integration of the ipped

classroom approach within an EFL private university in Indonesia.

e ndings underscored that conventional classrooms exhibited

augmented post-test scores in comparison to their ipped classroom

counterparts, potentially attributed to teacher-centric instructional

methods and technology-related variables. Nevertheless, a signicant

portion of students perceived ipped classrooms as catalysts for self-

reliant and dynamic learning experiences, with recognition of both

the merits and demerits associated with this approach.

In addition, Li et al. (2022) delved into the repercussions of

employing the ipped classroom paradigm within the sphere of EFL

instruction. eir inquiry strategically probed the manner in which

the ipped methodology can augment the acquisition of students’

communicative competence. e outcomes of their investigation cast

a revealing light upon the potential advantages associated with

integrating the ipped pedagogical approach into the domain of EFL

instruction, thus furnishing insights into the realms of inventive

language learning methodologies. In an exploration conducted by Liu

etal. (2022), salient revelations emerged regarding the ecacy of the

ipped framework in amplifying both writing prowess and the

utilization of metacognitive strategies. eir inquiry makes a notable

contribution to the comprehension of how the ipped classroom

conguration can positively inuence not only writing prociency but

also the maturation of metacognitive faculties in the context of

collaborative writing. Similarly, Shih and Huang (2020) centered their

inquiry on the adept application of metacognitive strategies among

college students in an EFL ipped classroom milieu. rough an

intricate analysis of students’ deliberate utilization of metacognitive

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 04 frontiersin.org

strategies, their research enriches the understanding of the intricate

dynamics underlying students’ cognitive processes and strategic

approaches within the ipped learning milieu.

Su Ping etal. (2020) also embarked on a scholarly exploration of

the trajectory undertaken by EFL students within the framework of a

ipped classroom, with a specic focus on a writing-intensive class.

Hailing from the educational landscape of Malaysia, their research

presents a distinctive vantage point that brings to light the array of

experiences and outcomes that unfold for EFL learners immersed in

a writing-centered ipped classroom setting. Engaging in a methodical

appraisal, Turan and Akdag-Cimen (2020) executed a comprehensive

dissection of the implementation of the ipped classroom

methodology in the context of English language instruction. eir

amalgamation of research ndings furnishes substantial revelations

into the overarching ecacy and repercussions of the ipped

pedagogical approach in the domain of language learning. is

synthesis substantially enriches the broader comprehension of the

multi-faceted dimensions inherent in the implementation of the

ipped approach. Delving into the intersection of pedagogy and

technology, Jiang etal. (2021) undertake an investigative expedition

into the amalgamation of automatic speech recognition technology

within the structure of a ipped classroom. eir inquiry unveils the

latent potential of technology to elevate the complexity of EFL

learners’ oral language capabilities, eectively interweaving modern

technological advancements with the foundations of the ipped

learning milieu. In another study, Karjanto and Simon (2019) explored

the application of the ipped classroom methodology in a Calculus

course situated within a cultural context inuenced by Confucian

heritage. ey designed a theoretical framework that integrated

elements such as Bloom’s taxonomy, English-medium instruction, and

the incorporation of technology. eir instructional design

encompassed four distinct approaches, including variations of the

ipped classroom model. e quantitative analysis yielded notable

ndings, revealing a signicant discrepancy in examination scores,

particularly evident when comparing fully-ipped instruction to

single-topic ipped instruction. Furthermore, their qualitative

investigations underscored positive enhancements in student

engagement and interactions with instructors. Nevertheless, they also

unearthed challenges linked to language, cultural factors, competition,

and the adaptation to technological tools.

Taken together, these studies contribute to the literature by

examining the ecacy of the ipped classroom approach in enhancing

various dimensions of EFL learning, including communication,

writing, metacognition, critical thinking, and oral language

prociency. eir insights resonate with the evolving landscape of

language education, oering valuable guidance for educators seeking

to embrace innovative pedagogical strategies to meet the diverse needs

of language learners.

Reading comprehension

Reading comprehension is a multifaceted skill that involves

various cognitive processes and strategies. According to Kintsch

(2012), reading comprehension entails the ability to connect existing

knowledge (schema) with the information presented in the text,

summarize key elements, draw appropriate conclusions, and enhance

understanding by posing probing questions. It encompasses the

process of constructing meaning from written texts, ranging from

recognizing individual symbols and linguistic units to synthesizing

and integrating information within a meaningful framework, thereby

engaging higher-order thinking skills (Kendeou etal., 2014; Zhang

and Zhang, 2022).

Comprehending a written text is a complex cognitive activity that

relies on several interconnected factors. It necessitates the activation

of prior knowledge, uency in reading, relevant past experiences, the

utilization of cognitive and metacognitive strategies, a strong grasp of

lexical and grammatical knowledge, the ability to organize

information, make judgments, and engage in reective evaluation

(Syatriana, 2011). Consequently, reading comprehension is recognized

as a challenging skill in internationally recognized tests such as the

International English Language Testing System (IELTS) and Test of

English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) (Pellegrino and Hilton, 2012;

Hung, 2015). Furthermore, several other variables can inuence

learners’ reading comprehension abilities. ese variables encompass

reading types, individuals’ attitudes toward reading, the methods

employed during reading activities, adaptability to dierent text

genres, and the strategies utilized by learners to comprehend the texts

eectively (Jeon and Yamashita, 2014; Zhang and Zhang, 2022). ese

factors interact and contribute to learners’ overall reading

comprehension performance (Jeon and Yamashita, 2014). Given the

complexity of reading comprehension and its signicance in academic

and language prociency assessments, it is imperative to further

explore various instructional procedures and their impact on learners’

comprehension abilities (Yapp etal., 2021). Also, understanding the

variables that aect reading comprehension can inform instructional

practices, curriculum design, and the development of eective

strategies to enhance learners’ reading skills.

Reading comprehension, a challenging process that contains

components, procedures, and aspects with the desire to discover great

ways of accelerating it, is an integrated process of generating meanings

from a reading section (Meniado, 2016). Besides, there appeared

several ways to improve EFL learners’ reading comprehension, for

instance, by incorporating online ipped classrooms, as supported in

the literature (Öztürk and Çakıroğlu, 2021; Samiei and Ebadi, 2021;

Fischer and Yang, 2022; Hasan etal., 2022; Mohammaddokht and

Fathi, 2022). According to Samiei and Ebadi (2021), WebQuest-based

ipped classroom signicantly enhances learners’ inferential reading

comprehension as revealed via the data analysis. In a similar study,

Hashemifardnia etal. (2018) examined how ipped classroom aects

junior high school students’ reading comprehension in EFL context.

ey stated that online ipped classrooms could substantially aect

reading comprehension. Although the signicance of ipped

classrooms in enhancing reading comprehension has received limited

exploration, the objective of this study is to contribute to the existing

literature by investigating the impact of online ipped classrooms on

the reading comprehension of EFL learners.

Self-regulated learning

In educational psychology, Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) stands

as a foundational construct, intrinsically linked with Zimmerman’s

theoretical framework (Zimmerman, 2000). Zimmerman posits that

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 05 frontiersin.org

human regulatory skill, or the lack thereof, holds a pivotal role in

shaping our perception of personal agency, which, in turn, forms the

very core of our self-concept (Zimmerman, 2000; Zimmerman and

Schunk, 2001). e development of this regulatory capability,

encompassing its subcomponents and functional aspects, has

remained a central focus of social cognitive theory and research

(Zimmerman, 2000; Zimmerman and Schunk, 2001).

Zimmerman’s comprehensive framework extends its purview to

elucidate common dysfunctions observed in self-regulatory

functioning, including phenomena such as biased self-monitoring,

self-blaming judgments, and defensive self-reactions (Zimmerman,

2000). In seeking to provide a holistic perspective on self-regulation,

Zimmerman’s framework addresses a multitude of facets. ese

include delving into the structural elements of self-regulatory systems,

discerning the inuences of social and physical environmental

contexts on self-regulation, investigating dysfunctions that may arise

within the realm of self-regulation, and exploring the developmental

trajectory of self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2000).

Within the realm of SRL, learners engage in a multifaceted set of

strategies that empower them to meticulously plan, closely monitor,

and critically evaluate their learning activities (Zimmerman and

Schunk, 2001). ese strategies, deeply ingrained in Zimmerman’s

model, serve as the scaolding upon which learners construct their

self-regulated learning processes. ey assume control over their

learning endeavors, establish meaningful goals, evaluate their

progress, and adapt their strategies judiciously to optimize learning

outcomes (Zimmerman and Schunk, 2001).

ese SRL strategies seamlessly align with three distinct phases:

Planning, Monitoring, and Evaluating. In the Planning phase, learners

undertake activities that lay the groundwork for eective reading

comprehension. is phase encompasses actions such as previewing

reading tasks, setting clear learning objectives, and formulating goals

before immersing themselves in the reading materials.

e Monitoring phase, on the other hand, hinges on learners’

adeptness at overseeing their reading progress and performance.

Strategies like self-checking comprehension, identifying challenging

sections, and making real-time adjustments during the reading

process epitomize this phase.

Lastly, the Evaluating phase revolves around the critical assessment

of the ecacy of one’s learning strategies and the attainment of

learning objectives. In this phase, learners engage in reection on their

reading experiences, conduct a thorough analysis of the success of

their approaches, and contemplate adjustments for future

learning endeavors.

In the specic context of English reading comprehension, the

application of SRL strategies assumes paramount importance.

Learners can substantially enhance their reading skills by proactively

employing SRL strategies that seamlessly align with Zimmerman’s

model. ese strategies, which traverse the planning, monitoring, and

evaluating phases, enable learners to not only navigate the intricate

landscape of reading comprehension eectively but also become

architects of their own learning experiences. In the planning phase,

learners prelude their reading journeys by engaging in activities such

as previewing reading tasks and crystallizing their learning objectives.

Subsequently, the monitoring phase calls for ongoing self-assessment

and vigilant tracking of progress during the reading process. Finally,

the evaluating phase encourages learners to engage in a

comprehensive assessment of their comprehension, scrutinize the

ecacy of their chosen strategies, and cra a roadmap for continued

learning success.

Self-regulated learning strategies hold signicant importance in

empowering students to assume agency over their learning process

and actively participate in their educational journey (Zimmerman,

2002). Self-regulation encompasses the development of a practical

understanding of one’s own abilities, enabling students to make

informed decisions and take appropriate actions to enhance their

learning experiences (Zimmerman, 2000; Pajares, 2009). Students

who possess a high level of self-regulation acquire the capacity to exert

control over their learning processes, actively constructing meaning,

establishing goals, making deliberate choices regarding the strategies

they employ, and assuming leadership in directing their own learning

(Zimmerman and Schunk, 2001; Pintrich, 2004). Moreover, they

eectively integrate contextual and personal factors into their learning

experiences, recognizing the interplay between these elements.

e utilization of self-regulated learning strategies results in

increased engagement and proactive learning among students (Nilson,

2023). ey develop the ability to monitor their progress, adapt their

learning strategies as needed, and demonstrate perseverance in the

face of challenges. is acquisition of self-regulation empowers

students to become autonomous learners, capable of adjusting their

approaches to dierent learning tasks and contexts, thereby enhancing

the eectiveness of their learning outcomes (eobald, 2021).

Furthermore, self-regulated learners display metacognitive awareness,

engaging in reection on their learning processes, evaluation of their

performance, and identication of areas for improvement (Andrade

and Evans, 2012). rough self-reection, self-evaluation, and self-

assessment, they continually rene their learning strategies,

optimizing their overall learning outcomes.

Blended teaching can make students autonomous in their

language learning process by planning to learn, having more pace for

selecting and sequencing the video- and audio-based content,

possessing ownership, making decisions, enhancing higher-order

learning skills, and observing learning to support self-regulated

learning strategies (Lai and Hwang, 2016; Tan etal., 2017; Van Laer

and Elen, 2017; Lee and Choi, 2019; Shih and Huang, 2020; Fathi

etal., 2023). Moreover, an online ipped classroom, as a blended

learning strategy, can oer authentic, meaningful, and personal

materials, oer learners control and provide sucient scaolding and

opportunities for interaction, reection, and cooperation (Van Laer

and Elen, 2017).

Within the context of online ipped classrooms, students are

called upon to employ a spectrum of self-regulated learning

strategies, encompassing cognitive, metacognitive, and behavioral

dimensions, to eectively navigate their pre-class tasks and

subsequently participate in in-class sessions (Geduld, 2016). e

cognitive facet entails strategies such as rehearsing, organizing,

transforming, and expanding knowledge, while metacognitive

strategies involve goal setting and performance monitoring.

Additionally, behavioral aspects encompass time and resource

management as well as note-taking practices (Karlen, 2016). ese

multifaceted strategies converge to form a cohesive skill set crucial

for successful EFL learning within the dynamic landscape of online

ipped classrooms.

Our focus on the interaction between ipped classrooms and

self-regulated learning not only acknowledges the evolving

demands placed upon learners but also sheds light on the symbiotic

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 06 frontiersin.org

relationship between instructional methodology and cognitive

autonomy. While prior research has indeed identied predictive

links between self-regulated strategies and ipped classrooms (Van

Alten etal., 2020; Öztürk and Çakıroğlu, 2021), our study seeks to

extend this understanding by validating and strengthening these

insights within a distinct educational setting. To this end, this study

aims to examine how online ipped classrooms can inuence EFL

learners’ reading comprehension and self-regulated learning

strategies quantitatively and explore its role in students’

perception qualitatively.

The present study

Although previous studies have explored the effectiveness of

flipped instruction and online learning in improving language

skills, there remains a need for more empirical research,

particularly in the form of comparative studies that directly

compare different instructional methods. This current study aims

to address this research gap by investigating the effectiveness of

three teaching methods–Online Flipped Instruction (OFI),

Flipped Instruction (FI), and Traditional Instruction (TI)–in

enhancing L2 reading comprehension performance and self-

regulation among students.

rough the examination of online collaborative ipped

instruction in the OFI group, traditional ipped instruction in the FI

group, and conventional instruction in the TI group, this study will

assess the impact of each method on students’ L2 reading

comprehension performance and self-regulation. Via directly

comparing these three approaches, the study will generate empirical

evidence to identify the most eective teaching method for enhancing

students’ language learning outcomes. Against this backdrop, this

study aims to answer the following research questions:

1. What are the comparative eects of the OFI, FI, and TI

methods on L2 reading comprehension performance?

2. What are the comparative eects of the OFI, FI, and TI

methods on L2 reading self-regulation?

3. Are there signicant dierences in online learning behaviors

and objective performances between students in the OFI and

FI groups?

By answering these research questions, this study aims to

contribute to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence

on the comparative eectiveness of dierent instructional methods in

promoting L2 reading comprehension and self-regulated learning of

Chinese EFL learners. e rationale behind the emphasis on this

specic student cohort (i.e., EFL learners) is rooted in the recognition

that diverse factors, including cultural, linguistic, and educational

backgrounds, can shape the implementation and outcomes of

instructional methodologies. e intricacies of English language

acquisition for Chinese learners (Wu, 2001), coupled with the

demands of academic reading skills, render this population

particularly intriguing for investigation. By delving into the

experiences and responses of Chinese English learners within the

realm of online collaborative ipped classrooms, this study aims to

unearth insights that can inform tailored pedagogical strategies,

curriculum design, and instructional support.

Method

Participants

e participants in this research were 71 EFL students, aged

between 18 to 30 years old, who were enrolled in an English

language course at a large language institute in mainland China. e

majority of the participants were females (n = 45, 63.4%) and the

rest of the students were males (n = 26, 36.6%). e participants had

varying educational backgrounds, with most of them holding a high

school diploma or equivalent (n = 54, 76.1%) and the remaining

participants had a bachelor’s degree (n = 17, 23.9%). Participants’

prociency level was determined based on the standardized

placement test, Test of English for International Communication

(TOEIC; Woodford, 1982), which is widely employed to evaluate

the English prociency of non-native speakers. Participants with an

intermediate prociency level (score range between 550 and 780)

were included in the study. e participants were divided into three

classes who were randomly assigned to a traditional instruction

(TI) group (n = 24), and two experimental groups: Flipped

Instruction (FI) group (n = 22) and Online Flipped Instruction

(OFI) group (n = 25).

While addressing potential concerns regarding the sample size,

insights were drawn from the recommendations of American

Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (2010), which

suggest that an optimal class size of approximately 15 students is

advisable for facilitating collaborative learning activities eectively,

especially within student-centered educational contexts. However,

it’s worth noting that collaborative learning can still beimplemented

with larger class sizes, such as the 22 students in our study. To

accommodate the larger class size while adhering to the principles

of collaborative learning, we strategically designed the ipped

instruction and online ipped instruction approaches, ensuring

that they were conducive to group interactions and active

engagement. is approach aimed to maintain the quality and

eectiveness of collaborative learning, even with a larger number of

students, thereby enhancing the reliability and validity of the

research ndings.

Measures

Reading comprehension

e participants’ reading comprehension ability was measured

using the IELTS reading test (University of Cambridge ESOL

Examinations, 2011). e IELTS reading test consists of three sections,

each containing one long reading passage with increasing diculty,

followed by a set of multiple-choice questions. e IELTS Academic

Reading test is a standardized assessment that consists of 40 questions

and is administered within a strict time limit of 60 min. e test aims

to assess the participants’ ability to comprehend and analyze academic

English texts. e IELTS reading test has been extensively employed

in L2 research, and has demonstrated good reliability and validity in

measuring reading comprehension ability.

According to Weir and O’Sullivan (2017), the post-1989 evolution

of IELTS primarily involves the transformation of the initial ELTS into

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 07 frontiersin.org

a legitimate, psychometrically sound, high-stakes assessment with the

capacity for widespread global administration on a large scale.

Moreover, current data from the IELTS website (IELTS, 2021) provides

comprehensive statistics for the test forms administered in 2019.

Specically, for the Reading section, the reported reliability coecient

stands at a robust value of 0.92, within a condence interval of 0.90

to 0.93.

Self-regulated learning strategy use

questionnaire

e Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) questionnaire utilized in this

study was developed by Tse et al. (2022) and was based on

Zimmerman’s (2000) cyclical phases model. e questionnaire

comprised 13 statements that assessed the employment of SRL

strategies in English reading. e statements were formulated

according to three categories of SRL strategies: planning, monitoring,

and evaluating. Planning involved activities such as previewing

reading tasks and setting goals prior to reading, whereas monitoring

referred to checking and monitoring one’s reading progress and

performance. Evaluating concerned the assessment of learning

outcomes and the eectiveness of strategies. Participants rated all

items using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never or almost

never) to 4 (every day or almost every day). e SRL strategy use

questionnaire exhibited robust internal consistency, attaining a

commendable coecient of reliability at r = 0.86 within the context of

this study.

Online quizzes

To thoroughly assess the participants’ engagement with the course

materials and their understanding of the content, a series of online

quizzes were administered on a weekly basis to both the OFI and FI

groups. ese quizzes were thoughtfully designed to serve multiple

purposes: to aid participants in their preparation for the subsequent

in-class activities, to reinforce their comprehension of the assigned

video lessons, and to evaluate their grasp of the core concepts relevant

to the course.

Each weekly quiz comprised a carefully curated set of questions,

ranging from 15 to 25in number. ese questions encompassed a

variety of formats, including multiple-choice and short-answer

questions, and were meticulously aligned with the main topics covered

in the video lessons. Importantly, the questions were intentionally

tailored to bridge the gap between the video content and the

overarching theme of English reading comprehension. By

incorporating elements of reading analysis, interpretation, and

application, these quizzes aimed to foster a deeper understanding of

the materials presented in the videos and to promote critical thinking

in the context of L2 reading.

roughout the 12-week course duration, a total of 10 quizzes

were administered. e quizzes were strategically spaced to

correspond with the course’s progression and to ensure that

participants had the opportunity to revisit and consolidate their

knowledge on a regular basis. e mean score obtained by each

participant across these quizzes was computed as an additional metric

of achievement. is mean score served to provide insights into the

participants’ consistent performance and their evolving

comprehension of the course materials. It is noteworthy that the quiz

scores contributed signicantly to the participants’ nal grades,

reecting their competence in grasping the course content. Specically,

the nal grades were calculated based on a comprehensive evaluation

framework, which included various components. ese components

encompassed the overall participation score (50%), comprising class

attendance (20%), quiz scores (20%), and assignments (10%).

Additionally, the nal grades considered the midterm test score (20%)

and the nal test (post-test) score (30%). is multifaceted approach

to assessment aimed to holistically gage the participants’ progress,

engagement, and achievement throughout the course.

Online learning behavior

Following Fischer and Yang (2022), the present study examined

three distinct online learning behaviors, encompassing regular online

log-on time, group video-watching time, and total online log-on

times. Each of these dimensions warrants attention and consideration

within the context of our research. Firstly, regular online log-on time

signies the temporal commitment learners invest in engaging with

the weekly assigned video lessons online. It reects the extent to

which students actively participate in the preparatory phase of ipped

classrooms, where they access and assimilate instructional content

independently before class. is dimension directly intersects with

the ipped classroom model, as it measures the conscientiousness

with which students approach their pre-class learning activities.

Secondly, group video-watching time stands as a critical component

of online learning behavior, capturing the duration during which

participants in the experimental groups jointly engage in watching

video lessons within small online groups. is dimension

encapsulates the collaborative aspect of the ipped classroom

approach, emphasizing the value of peer interaction and shared

learning experiences. It is an essential component that furthers our

understanding of how students engage with instructional materials

and with each other, highlighting the interpersonal dimension of

online learning. Lastly, total online log-on times amalgamate

individual regular online log-on times with the time spent in small

group video-watching sessions. is cumulative measure oers a

comprehensive perspective on students’ overall engagement with

online learning materials and activities. It underscores the holistic

nature of online learning behavior, recognizing that eective learning

in the digital realm encompasses both independent and

collaborative dimensions.

Importantly, these dimensions of online learning behavior closely

align with the tenets of self-regulated learning. SRL involves learners

taking charge of their learning processes, which includes planning,

monitoring, and evaluating their learning activities. e temporal

commitment demonstrated through regular online log-on times

resonates with the planning phase of SRL, where learners proactively

engage with course materials and set the stage for eective learning.

Group video-watching time correlates with the monitoring phase, as

it reects learners’ active involvement in tracking their progress

through collaborative engagement. Lastly, the cumulative measure of

total online log-on times speaks to the evaluation phase, wherein

learners assess their learning strategies and the eectiveness of their

collaborative endeavors.

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 08 frontiersin.org

Group video-watching time, on the other hand, exclusively

captured the amount of time that the experimental group participants

spent watching the video lessons in small online groups. Lastly, total

online log-on times represented the cumulative measure,

incorporating the individual regular online log-on times and the small

group video-watching times of the participants.

To examine participants’ online learning behaviors, weekly video

lessons and accompanying quizzes were uploaded onto the LMS used

in this study. Both groups (i.e., FI and OFI) participants were

instructed to watch the assigned videos on the LMS and complete the

quizzes before attending class. e LMS automatically tracked each

student’s log-on time for video viewing on a weekly basis. ese

log-on times were then aggregated to calculate the overall regular

online log-on time for each participant throughout the course.

Additionally, the students’ online activities, including video-watching

and collaborative quiz sessions, were recorded. e duration of each

online group session was calculated, resulting in the group video-

watching time. is analysis provided insights into the students’

collective time spent watching the assigned videos and collaborating

within the virtual environment, contributing to a comprehensive

understanding of their online learning behaviors. To explore

participants’ online learning behaviors, weekly video lessons and

accompanying quizzes were uploaded to the LMS employed in this

study. Both the Flipped Instruction and Online OFI groups were

directed to view the designated videos on the LMS and take the

quizzes prior to coming to class. e LMS automatically recorded

students’ log-on times for video viewing on a weekly basis, which were

then combined to determine their overall online log-on time

throughout the course.

Furthermore, students’ online engagement, encompassing video-

watching and collaborative quiz sessions, was meticulously logged.

e duration of each group session was calculated, resulting in the

compilation of group video-watching time. is analysis furnished

valuable insights into the collective time students invested in viewing

the assigned videos and engaging in collaboration within the virtual

learning environment. Consequently, it contributed to a

comprehensive comprehension of their online learning behaviors.

Procedure

All three groups in the study were instructed by the same teacher,

who had professional training in teaching English, specically in

academic reading skills. e course materials utilized in the study

were focused on academic English reading skills, with particular

emphasis on the learners’ prociency in the IELTS academic reading

test. e course lasted for 12 weeks, during which time all three

groups received 180 min of instruction per week, distributed over two

90-min sessions. Pre-tests and post-tests were administered during

the rst and last week of the course to measure the progress of

the learners.

In the traditional instruction (TI) group, the instructor employed

the traditional ‘sage on the stage’ method to deliver the course

materials and facilitate group exercises and activities. e classroom

sessions primarily involved teacher-led instruction, group exercises,

and activities. Pre- and post-test assessments were conducted by the

teacher. In the ipped instruction (FI) and online ipped instruction

(OFI) groups, the teacher played a more dynamic role, both inside and

outside of the classroom. In the classroom, the instructor designed the

curriculum, coordinated and supervised group activities, provided

feedback and answered questions, as well as conducted pre- and post-

test assessments. Beyond the connes of the traditional classroom

setting, the educator meticulously curated and presented pre-designed

video lessons, which were thoughtfully craed to integrate reading

comprehension exercises, textual analysis, and targeted reading

strategies directly into the video content. Additionally, the teacher

assumed responsibility for conceptualizing, producing, recording, and

rening these tailored video lessons to ensure a comprehensive and

eective approach to teaching reading skills and fostering self-

regulated learning. Furthermore, the instructor eciently oversaw the

organization and administration of course materials within the

educational institution’s designated learning management system. To

facilitate online interactions, the teacher harnessed the capabilities of

the Zoom Webinar video meeting web application. Moreover, during

the OFI group sessions conducted virtually, the instructor delivered

periodic feedback to foster an optimal learning environment.

In the weekly in-class sessions, the instructor began by providing

brief announcements and instructions, as well as answering students’

questions. en, for the remaining class time, the instructor divided

students into groups and engaged them in various exercises and tasks

to practice the weekly lesson content, which focused on reading skills

and strategies. All learners were exposed to the identical in-class

instruction. As part of their extracurricular learning, the FI students

engaged in independent viewing of the designated course video

lessons and subsequently undertook brief quizzes aligned with each

instructional video.

In contrast to the other groups, the OFI students were purposefully

grouped into small cohorts, consisting of no more than four

individuals. ese smaller groups fostered a conducive environment

for collaborative learning as they collectively watched the assigned

weekly video lesson online. roughout these sessions, the OFI

students actively engaged in collaborative discussions, exchanging

ideas, and jointly completing the video quizzes, thereby reinforcing

their understanding of the material as a unied entity. To facilitate

seamless communication and interaction during their online video

sessions, the small OFI groups eectively utilized Google Hangouts,

leveraging its features for synchronous video conferencing and real-

time collaboration. Consequently, their sessions were recorded and

securely submitted to the instructor for meticulous review and

insightful feedback.

It is noteworthy that the OFI students were explicitly informed

of the signicance of their weekly online video sessions. ey were

apprised that these sessions would bethoughtfully reviewed and

deliberated upon during the subsequent in-person sessions held on

a weekly basis. is ensured that the insights, discussions, and

collaborative eorts from the online environment seamlessly

integrated with the face-to-face instructional setting, fostering

continuity and cohesion in the students’ learning experiences. In

contrast, the TI students followed a dierent approach during their

weekly lessons. ese sessions encompassed a combination of

in-class instruction focused on delivering the course content and a

variety of engaging activities designed to enhance student

participation and comprehension. Commencing each session, the

instructor dedicated the initial half to comprehensive coverage of

the lesson materials, providing necessary explanations and

clarications to support student learning. Subsequently, the latter

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 09 frontiersin.org

portion of the session was dedicated to a range of interactive group

activities and tasks, specically designed to align with the lesson

topics and skills covered in the assigned readings. is format

emulated the structure and format adopted in the weekly in-class

sessions of the FI and OFI groups, ensuring consistency and

alignment across the instructional approaches employed throughout

the study (Table1).

Prior to the commencement of the study, all participants,

regardless of their assigned experimental group, underwent pre-testing

to establish baseline measurements of their reading comprehension

abilities and SRL strategies. e pre-tests were conducted during the

initial week of the course. Subsequently, upon completion of the

12-week course, post-tests were administered during the nal week to

assess the participants’ progress. e SRL strategy use questionnaire

was administered at the beginning and end of the course to gage any

changes in self-regulated learning behaviors and strategies. ese

assessments were conducted in a controlled classroom environment

to ensure consistent testing conditions for all participants. Participants

were instructed to respond to the pre- and post-tests and the SRL

surveys with their utmost attention and sincerity, as their responses

played a crucial role in evaluating the eectiveness of the instructional

approaches employed in this study. e test and survey data were

collected and analyzed to provide valuable insights into the impact of

the dierent instructional methods on reading comprehension and

self-regulated learning outcomes.

Data analysis

To analyze the data collected for this study, the researchers used

statistical soware SPSS. e rst research question was explored

using a paired-sample t-test to compare the mean scores of the pre-

and post-tests for the three groups (OFI, FI, and TI). Subsequently, to

examine potential distinctions in the post-test scores among the

groups, ANOVA was employed, supplemented by Fisher’s LSD

post-hoc analysis. Regarding the third research question, an

independent t-test was conducted to explore possible disparities in the

online learning behaviors and objective performances, specically the

average online quiz scores and nal course grades, between the two

experimental ipped groups (OFI and FI).

Results

e rst research question aimed to investigate which teaching

method–Traditional Instruction (TI), Flipped Instruction (FI), or

Online Flipped Instruction (OFI)–yielded the most signicant results

in terms of the students’ L2 reading comprehension performance. To

address this question, a paired-sample t-test was conducted to

compare the pre-test and post-test scores of the students in each

group. As seen in Table2, the results revealed that all three groups

showed signicant improvement in their reading comprehension

performance from pre-test to post-test. e mean scores of the

students in the FI and OFI groups increased from pre-test to post-test,

while the mean score of the TI group slightly decreased.

e paired-sample t-test results showed that all three groups

showed signicant improvement in their reading comprehension

performance from pre-test to post-test (TI: t = 3.79, p = 0.005; FI:

t = 5.09, p = 0.000; OFI: t = 6.74, p = 0.000). e OFI group showed the

highest improvement, followed by the FI group, and then the TI group.

To further examine which teaching method had the most

signicant eect on the students’ reading comprehension performance,

a one-way ANOVA was conducted. Table3 presents the results of the

ANOVA for reading comprehension. e results indicated a signicant

dierence between the groups in terms of their reading comprehension

performance [F(2, 68) = 3.61, p = 0.034].

Post hoc tests using the LSD method were conducted to determine

which groups were signicantly dierent from each other. Table 4

presents the results of the post hoc tests. e results showed that there was

a signicant dierence in reading comprehension performance between

the OFI and TI groups (p = 0.008), indicating that the OFI group had a

signicantly higher mean score than the TI group. Additionally, the

results revealed a signicant dierence between the FI and OFI groups

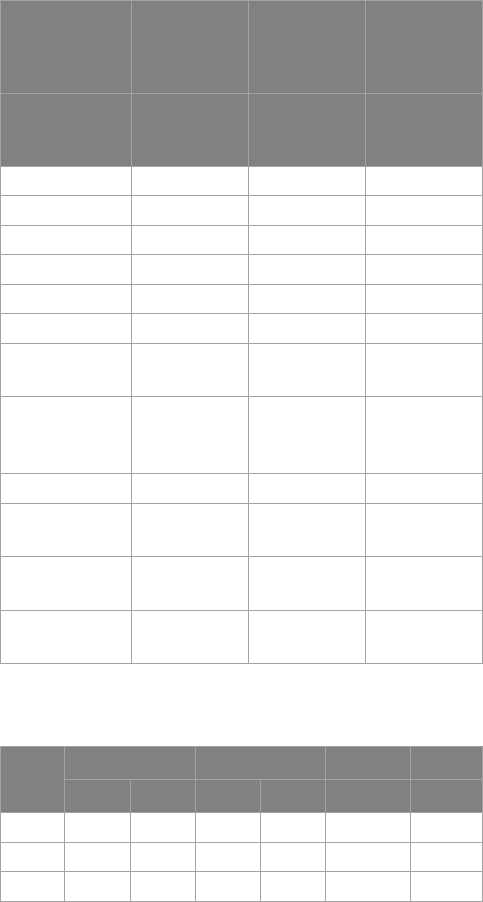

TABLE1 Main features of the reading intervention across experimental

groups.

Instructional

features

Traditional

Instruction

(TI)

Flipped

Instruction

(FI)

Online

Flipped

Instruction

(OFI)

Teacher’s

Role

‘Sage on

the stage’

method

Dynamic

role

Dynamic

role

Curriculum design Yes Yes Yes

Group activities Yes Yes Yes

Feedback and Q&A Yes Yes Yes

Pre- and post-tests Yes Yes Yes

Video lessons No Yes Yes

Online quizzes No Yes Yes

Specialized video

lessons

No Some Yes

Learning

management

system

No No Yes

Zoom webinar No No Yes

Collaborative

online sessions

No No Yes

Google hangouts

integration

No No Yes

Recorded sessions

review

No No Yes

TABLE2 Results of the paired-sample t-test for reading comprehension

Pre-test Post-test t p

M SD M SD

TI 5.12 0.66 5.66 0.56

3.79**

0.005

FI 5.18 0.72 6.08 0.72

5.09***

0.000

OFI 4.99 0.83 6.41 0.69

6.74***

0.000

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. TI, Traditional instruction; FI, Flipped Instruction; OFI, Online

ipped instruction.

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 10 frontiersin.org

(p = 0.031), indicating that the OFI group had a slightly higher mean

score than the FI group, although this dierence was not as big as the

dierence between the OFI and TI groups. Finally, there was also a

signicant dierence between the TI and FI groups (p = 0.023).

e second research question examined the dierences in self-

regulated learning strategies among students in the three teaching

methods. Based on the results of the paired-sample t-test for self-

regulated learning (Table5), the two ipped teaching methods showed

an increase in self-regulated learning from pre-test to post-test.

However, the largest increase was observed in the OFI group (M = 3.15,

SD = 0.68 to M = 4.35, SD = 0.67) with a signicant t-value of 7.32

(p < 0.001). e FI group also showed a signicant increase in self-

regulated learning (M = 3.21, SD = 0.89 to M = 3.93, SD = 0.83) with a

t-value of 4.30 (p < 0.01). e TI group, on the other hand, showed a

non-signicant increase in self-regulated learning (M = 3.28, SD = 0.71

to M = 3.41, SD = 0.75) with a t-value of 1.58 (p = 0.123).

Also, the results of the ANOVA for self-regulated learning in L2

reading (Table 6) indicate that there was a signicant dierence

between the teaching methods in terms of their eect on self-regulated

learning (F = 5.67, p = 0.012). e post hoc LSD analysis (Table 7)

revealed that the OFI group had a signicantly higher mean self-

regulated learning score (M = 4.35, SE = 0.19) than both the FI group

(M = 3.93, SE = 0.19) and the TI group (M = 3.41, SE = 0.19) with mean

dierences of 0.42 (p = 0.035) and 0.94 (p < 0.001), respectively.

Additionally, the FI group had a signicantly higher mean self-

regulated learning score than the TI group with a mean dierence of

0.52 (p = 0.015). Overall, it was found that both the FI and OFI

teaching methods resulted in a greater increase in self-regulated

learning in L2 reading compared to traditional instruction.

Furthermore, the OFI method yielded the highest increase in self-

regulated learning, suggesting that online ipped classrooms can bea

benecial approach for enhancing students’ self-regulation in

L2 reading.

e third research question addressed in this study was whether

there were signicant dierences in the online learning behaviors and

objective performances of OFI and FI students. Based on the results

of the independent-samples t-tests (see Table8) provided, there were

signicant dierences in the total online log-on time, online quiz

score, and nal score between the FI and OFI students. e OFI

students had a signicantly higher total online log-on time (M = 9.23 h,

SD = 3.27) than the FI students (M = 2.96 h, SD = 0.79), t = −5.234,

p < 0.001. e OFI students also had a signicantly higher online quiz

score (M = 89, SD = 16.54) than the FI students (M = 64, SD = 14.23),

t = −4.751, p < 0.001, and a signicantly higher nal score (M = 88,

SD = 14.97) compared to the FI students (M = 69, SD = 11.29),

t = −3.272, p = 0.008. ese results suggest that the OFI students had

better objective performances than the FI students in terms of online

quiz and nal score, and also spent more time online overall.

Discussions

e arrival of student-centered language education shed some

light on the signicance of implementing blended learning in EFL

classes. One such developmental move was an online ipped

classroom that could foster collaboration and cooperation, scaolding

(Topping and Ehly, 1998) and problem-solving (Barrows, 1996), and

exibility (Michael, 2006). us, the present study aimed to compare

the eectiveness of traditional instruction (TI), ipped instruction

(FI), and online ipped instruction (OFI) on the reading

comprehension and self-regulated learning strategies of EFL learners.

e ndings of the study revealed that both FI and OFI instructional

methods were more eective in improving students’ reading

comprehension scores compared to traditional instruction.

Furthermore, the OFI method showed signicant improvements in

students’ SRL strategy use compared to the other two groups. ese

results suggest that incorporating ipped and online ipped

instruction into EFL reading instruction may enhance students’

learning outcomes.

One of the noteworthy ndings of this study was the positive

impact of online ipped classrooms on the reading comprehension

abilities of EFL learners. e success of this approach can beattributed

to a range of eective strategies employed. ese encompass assigning

videos and reading tasks for completion outside the traditional

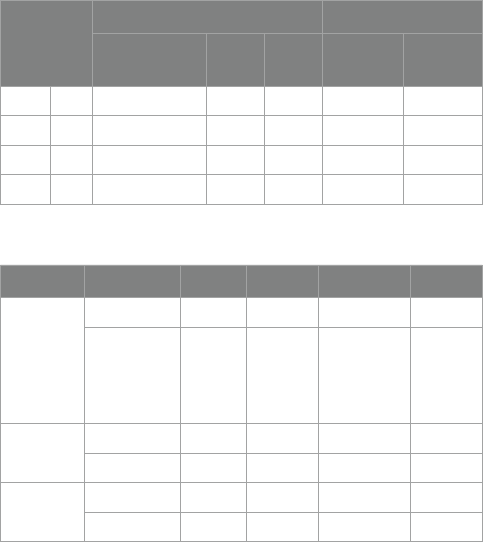

TABLE3 Results of ANOVA for reading comprehension.

SS df MS F P

Between

groups

3.02 2 1.51

3.61*

0.034

Within

groups

21.32 68 0.43

Tot al 24.35 70

*p < 0.05.

TABLE4 Results of post hoc LSD.

95% CI

Mean

dierence

SE p Lower Upper

(I) (J) (I–J)

TI FI 0.42 0.191 0.023 0.042 0.798

OFI TI 0.75 0.189 0.008 0.378 1.122

OFI FI 0.33 0.194 0.031

−0.048

0.708

TABLE5 Results of the paired-sample t-test self-regulated learning.

Pre-test Post-test t p

M SD M SD

TI 3.28 0.71 3.41 0.75 1.58 0.123

FI 3.21 0.89 3.93 0.83

4.30**

0.006

OFI 3.15 0.68 4.35 0.67

7.32***

0.000

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

TABLE6 Results of ANOVA self-regulated learning in L2 reading.

SS df MS F P

Between

groups

4.22 2 2.11

5.67*

0.012

Within

groups

36.75 68 0.64

Tot al 40.97 70

*p < 0.05.

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 11 frontiersin.org

classroom, facilitating collaborative reading tasks through online

communication platforms, and fostering reection and self-evaluation

of reading comprehension skills. ese strategies have been supported

by prior research, demonstrating increased motivation, engagement,

and productivity within the classroom (Strelan etal., 2020; Vitta and

Al-Hoorie, 2020).

ese results can beattributed to a combination of well-founded

strategies that EFL learners can eectively employ to enhance their

reading performance in the context of ipped classrooms. Firstly, the

practice of assigning videos and reading tasks for completion outside

of the traditional classroom plays a pivotal role. is approach

encourages learners to take ownership of their learning process,

fostering independence and self-directed study habits. By engaging

with course materials independently, students have the opportunity to

delve deeper into the content, preparing them for more meaningful

in-class discussions and activities. Secondly, the utilization of

collaborative reading tasks facilitated through online communication

platforms enhances the learning experience. It promotes peer

interaction and shared exploration of texts, enabling learners to benet

from diverse perspectives and insights. is collaborative dimension

not only enriches their understanding of the reading materials but also

cultivates crucial communication skills in an online context, aligning

with the demands of the digital age. Furthermore, the practice of

facilitating peer feedback exchange during reading activities fosters a

constructive learning environment. Learners actively contribute to

each other’s growth by providing valuable insights and critiques. is

not only bolsters their comprehension but also encourages a culture of

continuous improvement and mutual support. In addition, individual

and collective reection on reading practices is integral to the success

of ipped classrooms. Encouraging learners to assess their own reading

comprehension skills and engage in group discussions about their

strategies encourages metacognitive awareness. It empowers them to

adapt and rene their approaches to reading, leading to more eective

comprehension. Moreover, the promotion of self-evaluation of reading

comprehension skills empowers learners to take charge of their

progress. By regularly assessing their own understanding and

identifying areas for improvement, students become more self-aware

and accountable for their learning outcomes.

Finally, providing opportunities for communicative activities

beyond the connes of the classroom solidies the positive outcomes

of online ipped classrooms. ese activities allow students to apply

their reading comprehension skills in real-world contexts, reinforcing

their practical utility. As a result, they become more motivated,

engaged, reective, and productive within the classroom environment.

ese ndings align with the research of Strelan etal. (2020) and Vitta

and Al-Hoorie (2020), underscoring the eectiveness of these

instructional approaches. By implementing these strategies, educators

can harness the power of online ipped classrooms to elevate student

motivation, engagement, reection, and productivity. Ultimately,

learners actively participate in critical discussions, engage in the

negotiation of meaning, and emerge with a deeper understanding of

the reading materials.

e eectiveness of these strategies is substantiated by prior

research (Guo, 2019; Fulgueras and Bautista, 2020; Mohammad

Hosseini etal., 2020; Shih and Huang, 2020; Samiei and Ebadi, 2021;

Yulian, 2021; Fischer and Yang, 2022) which has consistently

demonstrated their ecacy in improving EFL learners’ skills in

general and L2 reading in particular. Also, the results of the study are

consistent with previous research that has found that ipped

instruction can lead to increased student engagement and achievement

(Strayer, 2012; Bergmann and Sams, 2014; Stöhr etal., 2020; Turan

and Akdag-Cimen, 2020). Flipped instruction allows students to take

control of their learning by providing them with access to course

materials outside of class and enabling them to review and study at

their own pace. e results of the current study also support the

ndings of previous research that has found that online learning can

bean eective method of instruction (Bernard etal., 2009).

It was also revealed that online ipped instruction had a more

signicant eect on L2 reading comprehension of the EFL participants

than ipped instruction. is dierence can beattributed to several

key factors. Firstly, the essence of the ipped classroom model, as

conceptualized by Bergmann and Sams (2014) and Su Ping etal.

(2020), revolves around providing students with pre-class access to

instructional materials. is empowers them to progress through the

content at their own pace, ensuring a foundational understanding

before engaging in more dynamic and participatory in-class activities.

is advantage is further magnied when executed through online

platforms (Stöhr etal., 2020), where students can eciently allocate

their in-class time for focused practice and interactive learning

experiences (Hew etal., 2020).

Additionally, a body of prior research underscores the potency of

technology-based instruction, particularly the use of online materials

and multimedia resources, in augmenting language learning outcomes

(González-Lloret, 2019; Jain etal., 2023). e dynamic and interactive

nature of technology-supported learning environments can

substantially contribute to language skill development (Yang etal.,

2021). By providing our students with accessible online materials

tailored to their individual learning pace, the online ipped instruction

approach likely fostered a deeper engagement with the content and a

more eective honing of their reading skills.

TABLE7 Results of post hoc LSD.

95% CI

Mean

dierence

SE p Lower Upper

(I) (J) (I–J)

TI FI 0.52 0.192 0.015 0.097 0.943

OFI TI 0.94 0.191 0.000 0.516 1.364

OFI FI 0.42 0.196 0.035 0.026 0.814

TABLE8 Results of the independent-samples t-test.

Group M SD t p

Tot al

online

log-on

time

(hours)

FI 2.96 0.79

– 5.234***

0.000

OFI 9.23 3.27

Online

quiz score

FI 64 14.23

– 4.751***

0.000

OFI 89 16.54

Final score FI 69 11.29

– 3.272**

0.008

OFI 88 14.97

**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Wang 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1255389

Frontiers in Psychology 12 frontiersin.org

Furthermore, the integration of multimedia resources within our

online materials played a pivotal role in sustaining student engagement

and motivation (Shin etal., 2020). is multimedia-rich environment

not only catered to diverse learning preferences but also injected an

element of interactivity, capturing and sustaining student interest

throughout the learning process.

Previous research also supported that reading comprehension

could beenhanced by engaging learners in an online ipped classroom

model (Karimi and Hamzavi, 2017; Hashemifardnia et al., 2018;

Samiei and Ebadi, 2021). As reading comprehension involves

associating the background knowledge with the reading text, EFL

learners who are connected to the internet and can search around any

topic become able to create the background knowledge before starting

their reading due to their time exibility outside of class. Participating

in online ipped classrooms empowers EFL learners, providing them

with the agency and autonomy to make informed decisions and take

purposeful actions in their reading practices (Fulgueras and Bautista,

2020). is pedagogical approach fosters a sense of ownership and

responsibility in learners, motivating them to adapt and rene their

reading strategies, and explore novel approaches and techniques

(Fischer and Yang, 2022). Furthermore, online ipped classrooms

cultivate a positive attitude toward the inherent challenges of

comprehending texts, encouraging learners to perceive these

challenges as opportunities for personal growth and deeper

understanding (Samiei and Ebadi, 2021).

Moreover, EFL learners derive signicant benets from the

opportunity to enhance their vocabulary and grammatical knowledge

through engaging with various activities before, during, and aer

reading texts (Turan and Akdag-Cimen, 2020). ey actively employ

a range of strategies to strengthen their language prociency, including

the use of dictionaries to clarify unfamiliar words, the application of

contextual cues to predict and infer meaning, engaging in peer

discussions to seek clarication and deepen understanding, and

employing eective organizational strategies such as rehearsal,

rereading, and summarization. By skillfully utilizing these cognitive

and metacognitive strategies, learners cultivate an enriched reading

process that facilitates comprehensive comprehension and fosters