SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

1

INTEGRATED ENGLISH CORE

2024 SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

The IEP integrates the teaching of speaking, listening, reading, and writing in a task-based

syllabus organized by themes. Members of the Integrated English Program committee at present,

or in the past: Professors Erica Aso, Naoyuki Date, Joseph Dias (IEP Co-coordinator), Andrew

Reimann (IEP Co-coordinator), James Ellis (past IEP Co-coordinator), Matsuo Kimura, Azusa

Nishimoto, Wayne Pounds, Peter Robinson, Hiroko Sano, Don Smith, Minako Tani, Mitsue

Tamai-Allen, Naomi Tonooka, Jennifer Whittle, Teruo Yokotani, Hiroshi Yoshiba, Michiko

Yoshida, and Gregory Strong (past IE Co-coordinator and course writer).

This is the 31

st

year of the IEP and the IE Core Scope and Sequence and the IE Resource

Book for teachers have been augmented with many suggestions from the adjunct faculty

in the English department at Aoyama Gakuin University. Among the many contributors,

we particularly wish to acknowledge are Melvin Andrade, Deborah Bollinger, Jeff Bruce,

James Broadbridge, Loren Bundt, Vivien Cohen, Todd Rucynski, Joyce Taniguchi,

Masumi Timson, Yoko Wakui, and Jeanne Wolfe. Thanks are due to Denis Fafard for

source material on teaching learning strategies and to Nancy Yildiz for her ideas on

reading.

Copyright, Aoyama Gakuin University

Gregory Strong, 29 March, 2024

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

2

CONTENTS

Sequence of Instruction ………………………………………….

Program Organization ………………..…………………………..

Professional and Online Resources ………………………………

Grading Students …………..………………...…………………..

Language Learning Tasks ….………………………………….....

Keeping a Journal ………………………………………………..

Xreading ………………………………………………………….

Reading Two Novels ………………..…………………………...

Leading a Discussion ………………………..…………………..

Discussions at the Chat Room …………………………………..

Vocabulary .……………………………………………………..

Assessing Discussions ………….……………………………….

IE II Poster Presentations ……….……………………………….

IE III In-Class and Off-campus Interviews .………...….………..

IE III Rating Presentations ………...….……..…………………..

IE III Debates …………………………………………………....

PSAs and Commercials ……....….…………………...………….

4

12

14

20

29

32

34

44

52

65

68

75

76

79

86

90

97

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

3

NOTICE TO STUDENTS: PLAGIARISM

Plagiarism occurs when you take another person’s ideas or words without properly acknowledging them. If you

take information from other sources (e.g., books, academic journals, podcasts, or Web pages), you must cite these

sources properly. Of course, copying another student’s work is plagiarism, too. In the IE Program, you will learn

how to make citations. It is your responsibility to avoid all plagiarism.

When is it necessary to cite sources?

In some cases, for example, in journal writing or when expressing personal opinions, your writing may be

based on your own experiences and make use of your personal background and common knowledge. In

such cases, you don’t need to cite sources because YOU are the source. However, most academic writing

requires the use of material from other sources and you must note the information and its source.

Submitting an assignment with even one part taken from another source is plagiarism unless you cite the

source properly. You may quote directly from a source with proper citation, but it is better to paraphrase

or summarize information in your own words rather than just copy part of it. But even when you

paraphrase or summarize information, you still must cite the original source. Be careful if the statement,

“Free use is allowed” appears on a Web page. Use of any material without citing the source is

plagiarism.

What is the IE Program Plagiarism Policy?

Plagiarism of any assignment in any IE course – including Academic Writing and Academic Skills – will

lead to failure on that assignment, without the option to rewrite. If a student plagiarizes on a second

assignment, s/he will fail the entire course. IE Program teachers are very experienced at identifying

plagiarism, and all cases must be reported. In addition, a database is being created of all IE assignments

that students turn in. This will identify any reports, essays, or other assignments if another student copies

any of this work and tries to hand it in.

What are other consequences of plagiarism?

Being caught plagiarizing can have a negative effect on you. In some cases, there are legal and

financial results. For example, an author may sue someone who plagiarizes his/her work.

Benefits of original, plagiarism-free work

Here are some ways that you and your classmates can benefit from avoiding plagiarism:

* Your English skills will develop more rapidly.

* You will be able to express your own ideas and opinions.

* You will be able to communicate better with others.

* You can take pride in your accomplishments.

* Students will not feel pressured or bullied by classmates who want to copy their work.

* You will help preserve the reputation for excellence in English that AGU and the English Department

have built over many years and you will help other English majors in job-hunting.

Current Policy on ChatGPT & Generative AI: https://aogaku-

daku.org/policies-on-chatgpt-and-other-generative-ai/

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

4

I. SEQUENCE OF INSTRUCTION

The following Sequence of Instruction is for teaching IE Core classes. The schedule indicates

when a particular theme and when tasks such as discussions or a book report should be

introduced. Much of the classroom activity in an IE Core class involves pair and small group

work and should be based on the themes found in IE levels I, II, and III. In IE Level I and II,

teachers are to use a combined skills textbook, Interchange 2 (5

th

ed.) by Jack Richards, with

Jonathan Hull and Susan Proctor (Cambridge: CUP, 2017). It has been used mostly for speaking

and listening in the past, but the new edition has many reading activities for skimming and

scanning which we would like you to use in IE I and II Core classes.

We hope that you will make a conscious effort to get your students to recycle the vocabulary

from the readings for IE I, II, and III Core classes including from students’ media discussions as

well as the academic vocabulary they are learning in their listening classes. Encourage

students to use their new vocabulary productively in their discussions and writing -- including in

their weekly Core journals or blogs. A page with the vocabulary and page references is included

in the IE Core and Writing student booklets as well as in this teachers’ guide. In a given class,

teachers might note some vocabulary words on the board and use them in a speaking activity.

Some video materials are from CNN Master Course: Video-Based English, Culture Watch,

Business Watch, Focus on the Environment, the CINEX series of captioned videos, other

commercial videos, and Interchange 1 and 2. The CNN Master Course, Culture Watch, and

Business Watch series are for use at IE Level I and IE Level II. They are easier than the Focus on

the Environment series, reserved for IE III. All are in the Teacher Resource Center.

I.(a) WEBSITES

The Internet TESL Journal is a monthly web-based magazine that began in 1995. In addition to

the articles that appear online, it includes many activities for teachers (http://iteslj.org/t/). These

consist of games, jokes, language lessons, task-based activities, vocabulary quizzes, and more.

Joseph Dias, the co-coordinator of the IEP, also maintains a page of links to good ESL resources.

http://www.cl.aoyama.ac.jp/~dias/esllinks.html.

I.(b) SELF STUDY

One feature of the 5th edition of Interchange 2 is that the textbook comes with a password for

web access to self-study materials online. These could be introduced in class.

I.(c) SOUND FILES AND CDs FOR LISTENING

The listening files for the new Interchange 2 can be downloaded for free at the following website

and inputting the volume number (2) and the units:

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

5

http://www.cambridge.org/jp/cambridgeenglish/catalog/adult-courses/interchange-5th-

edition/resources

You can download the files onto a USB and then onto a PC (you can sign out a PC in the

teachers' rooms) or you could load the files onto your tablet and play it in class. We have also

ordered some CDs for the Teachers’ Resource Center which you can sign out for one day periods.

IE I: Tasks, Themes, Texts, Grammar, Vocab, Video

Discussion

⦁ Introduce discussions, practice discussions, sign-up, vocabulary,

teach different turn-taking phrases

Journal

⦁ Introduce journals, check 1st week’s journals, pick partners

Extensive Reading (E.R.)

⦁ Introduce students to Xreading website and provide an orientation to

manipulating it, choosing a digital reader, E.R.’s purpose and value.

1st Book Report

⦁ Teach literary terms, bring books to class, Sustained silent reading,

(S.S.R.), pair-sharing (optionally, students may use a physical book)

Plagiarism

⦁ Explain policy, examples of plagiarism, begin exercises:

Skill building:

a) “Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/563/01/

b) “Paraphrase and Summary Exercises”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/exercises/32/41

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

6

IE I THEMES

Interchange 2 (5

th

ed.)

GRAMMAR, VOCABULARY,

READING, SPEAKING

Childhood - “Good

Memories”:

(pp.2-8);

Grammar:

3# Past tense (p.3);

8# Used to (p.5)

Vocabulary: 6# Word Power (p.4): amusement park, beach, collect, playground

Reading: 13# Reading, “The Frida Kahlo Story” (scanning) (p.7): cast, courage,

destiny, injury, recognize

Speaking: “In the past…(p.14), Survey about your town (p.15) Interchange 1#

“We Have a Lot in Common” (p.114 )

Spirited Away (bilingual DVD in the AV Library) 778-MI88S; Culture Watch:

Segment 7: Why Girls Lose Their Self-Confidence in Their Teens (p.61-70),

Interchange 1: Unit 5: What Kind of Movies Do You Like? Unit 8: What Kind of

Music? Interchange 2: Unit 5, Has Anyone seen the Tent? Unit 12, Welcome Back

to West High; Spirited Away (bilingual DVD in the AV Library) DVD 778-MI88S;

Culture Watch: Segment 7: Why Girls Lose Their Self-Confidence in Their Teens

(p.61-70), Interchange 1: Unit 5: What Kind of Movies? Unit 8: What Kind of

Music? Interchange 2: Unit 5, Has Anyone seen the Tent? Unit 12, Welcome Back

to West High, Big Man Japan, Canadian Animation: (Every Child), The Golden

Compass, It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, The Indian in the Cupboard,

Kramer vs Kramer, Matilda, Merry Christmas, Mr. Bean, The Golden Compass,

Peanuts Classic Holiday Collection: Charlie Brown Christmas, Charlie Brown’s

Thanksgiving, The Pursuit of Happyness, The Secret Garden

Urban Life –

“Making Changes”

(pp.16-17)

Grammar:

3# evaluations and

comparisons (p.17)

9# Wish (p.20)

3# Grammar Focus (p.17): big, bathrooms, bedrooms, convenient, expensive,

modern, noisy, parking spaces, private

Reading: “The Man with No Money” (skimming) (p.21)

Speaking: Role Play, “For Rent” (p.28)

CNN: Black Americans: Unit 6: (p.43-49), Culture Watch: Segment 2: Spike Lee on

his movie Do The Right Thing (p.11-20); Segment 3: Those Terrible Taxis!

(p.21-30), Interchange 1: Unit 11: Help is Coming (Crime Suspects); Unit 12: A

Suburban House; Unit 14: Over Golden Gate Bridge, Interchange 2: Sequence 1:

What Do You Miss Most? Sequence 3: A Great Little Apartment, Interchange 2 (4

th

ed.): Sequence 9: To Buy a Car or Not, Green Talk: (Boomsville, The

Quiet Racket, What on Earth), Eight Mile, Hollywood Salutes Canadian Animation:

(Neighbours, Special Delivery, The House That Jack Built, The Street, Walking),

Mosaic1: Welfare Payments, Victim Support Group, Places in the Heart

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

7

Plagiarism: ⦁ Paraphrasing:

a) “Paraphrasing Exercise”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/619/02/

b) “Paraphrasing Exercise (Sample answers)”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/619/03/

Food – “Have You

Ever Tried That”

(pp.22-27)

Grammar:

4# Simple past vs. present

perfect (p.23); 10#

Sequence adverbs (p.25)

Vocabulary: 8# Word Power (p.24): bake, boil, fry, grill, roast, steam

Reading: “Pizza: The World’s Favorite Food?” (scanning) (p.27)

Speaking: Role Play, “Reality Cooking Competition” (p.29)

Videos: CNN: Unit 1: Food and Baseball Players (p.1-8); Unit 4: Unsafe Food

(p.25-33), Interchange 1: Unit 20: American Ethnic Food, Interchange 2: Sequence

8: Thanksgiving Documentary, Interchange 2, (4

th

ed.): Sequence 4: What’s

Cooking, Sequence 7: How to Frost a Cake, Mosaic1: Bottled Water

Plagiarism ⦁ Knowledge building:

a) “Reference List: Electronic Sources”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/10/ (APA)

Travel: “Hit the

Road” (pp.30-35;

Grammar:

3# Future with be going to

and will (p.31); 7# Modals

for necessity, suggestion

(p.33)

Vocabulary: 4# Word Power (p.32): ATM card, backpack, carry-on bag, cash,

first-aid kit, hiking boots, medication, money belt, passport, plane tickets, sandals,

suitcase, swimsuit, travel insurance, vaccination

Reading: “Adventurous Vacations” (skimming) (p.35)

Speaking: Interchange 2# “Top Travel Destinations” (p.115 ) “Interchange 5A#

“Fun Trips,” 5B#, (p.118, p.120)

Videos: CNN: Unit 5: What to Take on a Trip (p.36-42); Unit 2: Tamayo Otsuki,

Japanese Comedienne in America (p.9-16), Interchange 2: Sequence 2: Wait for

Me, Sequence 13: Street Performers, The Gold Rush, Interchange 2, (4

th

ed.):

Sequence 2: Victoria Tours

Plagiarism ⦁ Truth or Consequences

a) https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/929/04/ (articles below)

b) https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/929/05/ (handout)

“Hamilton President Resigns Over Speech”http://www.nytimes.

com/2002/10/03/ nyregion/hamilton-president-resigns-over- speech.html

“Fame Can’t Excuse a Plagiarist” http://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/16/

opinion/fame-can-t-excuse-a-plagiarist.html

“Washington Post Blogger Quits after Plagiarism Accusation”

“Hungary’s President Quits Over Alleged Plagiarism”

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/25/business/25post.html?_r=0

http://edition.cnn.com/2012/04/02/world/europe/hungary-president-

resigns/index.html?iref=allsearch

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

8

IE II: Tasks, Themes, Texts, Grammar, Vocab, Video

Discussion

⦁ Introduce/review discussions, practice discussions, sign-up,

vocabulary, teach different turn-taking phrases

Journal

⦁ Introduce journals, check 1st week’s journals, pick partners

Extensive Reading (E.R.)

⦁ Introduce students to Xreading website and provide an orientation to

manipulating it, choosing a digital reader, E.R.’s purpose and value.

1st Book Report

⦁ Teach literary terms, bring books to class, Sustained silent reading,

(S.S.R.), pair-sharing (optionally, students may use a physical book)

Plagiarism:

⦁ Explain policy, provide examples of plagiarism:

a) “Is it plagiarism yet?”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/589/02/

II THEMES

Interchange 2 (5

th

ed.)

GRAMMAR, VOCABULARY,

READING, SPEAKING

Changing Times –

“What do you use

this for?” (pp.44-49)

Grammar:

3# Infinitives and

gerunds; (p.45); 8#

imperatives and infinitives

for giving suggestions

(p.47)

Vocabulary: 5# Word Power (p.46): check in for a flight, computer whiz,

computer crash, download apps, early adopter, edit photos, flash drive, frozen

screen, geek, hacker, identity theft, make international calls, phone charger, smart

devices, software bugs, solar-powered batteries

Reading: 12# “The Sharing Economy--Good for Everybody?” (skimming) (p.49)

makes, loses; give to, receive from; dangerous, safe; rules, people; equal, different

Videos: Business Watch: Segment 11: TV Technology (101-110) Culture Watch:

Segment 11: Computers and the Consumers: User-Friendly or User-Surly? (p.101-

110), Interchange 2: Sequence 7: Great Inventions Interviews, Sequence 9: A Short

History of Transportation, Interchange 2, (4

th

ed.): Sequence 3: The Right

Apartment, A.I., Back to the Future, Modern Times, 2001: A Space Odyssey

The Workplace –

“I Like Working

with People”

Vocabulary: 8# Word Power (p.67): creative, critical, disorganized, efficient,

forgetful, generous, hardworking, impatient, level-headed, moody, punctual, reliable,

strict (pp.67)

Reading: 12# “Global Work Solutions” (skimming) (p.69)

Speaking: Discussion, “Job Profile” (p.71); Interchange 10# “You’re Hired” (p.124 )

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

9

(pp.64-69);

Grammar:

3# Gerunds; short

responses (p.65); 10#

Clauses with because

(p.68)

Videos: Business Watch: Segment 9: On the Road Again (motorcycles) (p.81-90);

Segment 10: Flexibility of Companies to Family Care Needs (p.91-100) Culture

Watch: Segment 9: PG & E Trains Women for Construction and Men's Jobs (p.81-90)

Interchange 1: Unit 2: Career Change; Unit 4: Job Titles Interchange 2: Sequence 10:

Mistaken Identity; Sequence 14: Mrs. Gardener’s Promotion, Interchange 2 (4

th

ed.):

Sequence 14: Body Language of Business – How to Ace a Job Interview, Sequence 9:

Job Interviews, Chalk, Freedom Writers, Modern Times, Mosaic1: High-Tech Jobs

and Low-Tech People, North Country, Room 22, The Shop Girl, Steel Magnolias

Plagiarism: ⦁ Skill building:

a) “Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/930/02/

Geography – “It’s

Really Worth

Seeing” (pp.72-77;

Grammar:

3# Passive with by

(p.73); 9# Passive

without by (p.75)

Vocabulary: 7# Word Power (p.74) cattle, dialects, electronics, handicrafts, sheep,

souvenirs, soybeans, textiles, wheat

Reading: 13# “Advertisements” (p.77)

Speaking: Interchange 11# “True or False” (p.125)

Videos: Culture Watch: Segment 12: What's Become of Hollywood? (p.111-120)

Business Watch: Segment 4: Disney's Strategy (p.31-40), Interchange 1: Unit 18:

Around the World Game Show (travel videos) It's a Great Place (Vancouver);

Everest, Inside Islam

Plagiarism: ⦁ Paraphrasing:

a) “Paraphrasing”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/976/02/

Autobiography –

“It’s a Long Story”

experiences

inspirational

stories (pp.78-83)

Grammar:

3# Past continuous vs.

simple past (p.79);

8# present perfect

continuous (p.81)

Vocabulary: 5# Word Power (p.80) coincidentally, fortunately, luckily,

miraculously, sadly, strangely, surprisingly, unexpectedly, unfortunately

Reading: “Breaking Down the Sound of Silence” (p.83)

Speaking: Interchange 12# “It’s My Life” (p.126)

Videos: CNN: Unit 12: Family Trees (p.97-107) Culture Watch: Segment 4: Maya

Angelou, Inaugural Poetess (p.31-40); Segment 5: Paul Simon (p.41-50); Segment 8:

Hillary Rodham Clinton (p.71-80) Bend It Like Beckham, The Cove, Freedom

Writers, Hurricane, Modern Times, The Pursuit of Happyness

Plagiarism: ⦁ Paraphrasing:

a) Inappropriate Paraphrase (Penn State Plagiarism Tutorial)

http://tlt.psu.edu/plagiarism/student-tutorial/paraphrase/

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

10

IE III: Tasks, Themes, Texts, Grammar, Vocab, Video

Discussion:

⦁ Introduce/review discussions, practice discussions, sign-up,

vocabulary, teach different turn-taking phrases

Journal:

⦁ Introduce journals, check 1st week’s journals, pick partners

1st Book Report:

⦁ Teach/review literary terms, bring books to class, SSR, pair-sharing

Plagiarism:

⦁ Explain policy, provide examples of plagiarism, begin exercises:

a) “Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/930/02/

b) “Paraphrasing”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/976/02/

Plagiarism:

Knowledge building:

a) “Comparing Policies”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/929/14/

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/929/15/ (handout)

III THEMES

Interchange 2 (5

th

ed.)

GRAMMAR, VOCABULARY,

READING, SPEAKING

Psychology - "I

Wouldn’t Have

Done That"

(pp.100-105;

Grammar:

3# Unreal conditional

sentences with if clauses

(p.101); 8# Past modals

(p.103)

Vocabulary: 6# Word Power (p.102) accept, admit, agree, borrow, deny,

disagree, dislike, divorce, enjoy, find, forget, lend, lose, marry, refuse,

remember, save, spend

Reading: 13# “Toptips.com” (skimming) (p.105)

Speaking: “An Awful Trip” (p.104); Interchange 15# “Tough Choices” (p.130 )

Videos: Interchange 2: Sequence 16: A Wonderful Evening, American Beauty,

City Lights, City of Joy, Father of the Bride, My Best Friend’s Wedding, Shop Girl

Steel Magnolias

Plagiarism: ⦁ Quotation Marks:

a) “Using Quotation Marks”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/01/

b) “Extended Rules for Using Quotation Marks”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/02/

c) “Additional Rules for Using Quotation Marks”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/03/

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

11

Cross-Cultural

Values – “Time to

Celebrate!”

cultural values

(pp.50-55)

Grammar:

4# Relative clauses of

time (p.51); 10#

Adverbial clauses of

time (p.54)

Vocabulary: 5# Word Power (p.50) eat, give, go to, have a, play, send, visit,

watch, wear

Reading: “Out with the Old, In with the New” (skimming) (p.55)

Speaking: Interchange 8# “It’s Worth Celebrating” (p.122)

Videos: Interchange 2: Sequence 2: What Do You Do, Miss? Sequence 15: How

Embarrassing, A Rabbit-proof Fence, Baraka, Bend It Like Beckham, City of Joy,

The Day I Became a Woman, Departures, Father of the Bride, God Grew Tired of

Us, Gulliver’s Travels, Happy Feet, A Life Apart, Lost in Translation, Monsoon

Wedding, Obachan’s Garden, Persepolis, Silence, Slumdog Millionaire, Turtles

Can Fly, Wadja, Whale Rider

Plagiarism: ⦁ More Quotation Marks:

a) “Quotation Marks with Fiction”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/04/

b) “Quotation Marks Exercise (with answers)”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/577/05/

Environment - Life

in the City

(pp.8-13);

Grammar:

3# Expressions of

Quantity (enough, fewer,

more, too many), (p.9);

9# Indirect questions

(p.11)

Vocabulary: 1# Word Power (p.8): (compound nouns) bicycle, bus, center, garage,

green, jam, recycling, space, stand, station, stop, street, subway, taxi, system,

traffic, train

Reading: 13# “The World’s Happiest Cities” (skimming) (p.13): entertainment,

housing, natural areas, safety, schools, transportation Happy Feet, Suzuki

Speaks, Whale Rider, Who Killed the Electric Car?

Videos: Focus on the Environment: Segment 1: Little Done to Stop Animal and

Plant Extinction (p.1-12); Segment 9: Recycling and Trash Problems (p.97-108) An

Inconvenient Truth, Children of Men, The Cove, The 11

th

Hour, Gorillas in the

Mist, Mosaic 1: Air Pollution, Never Cry Wolf, New Moon Over Tohoku, Suzuki

Speaks, Whale Rider, Who Killed the Electric Car?

Plagiarism: ⦁ Knowledge building:

a) “Plagiarism & You” (Penn State pdf)

http://www.libraries.psu.edu/content/dam/psul/up/lls/documents/

PlagiarismHandout2012.pdf

Skill building:

a) “APA In-text Citations: The Basics”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/560/02/

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

12

The Media - “That’s

Entertainment!”

(pp.86-91)

Grammar:

3# Participles as

adjectives (p.87); relative

pronouns for people and

things (p.89):

Vocabulary: amusing, bizarre, disgusting, dumb, fantastic, funny, hilarious,

hysterical, incredible, odd, outstanding, ridiculous, silly, stupid, strange, weird,

wonderful (p.87)

Reading: “The Real Art of Acting” (scanning) (p.91)

Speaking: Interchange 13# (p.127)

Videos: Broadcast News, Cannes Bronze Commercials, Commercials from

Around the World, Commercials Worldwide, Mosaic 1: Internet Publishing, The

5

th

Estate, Get Up Eight, Seven Times, Snowden

Plagiarism: ⦁ Knowledge building:

a) “Comparing Policies”

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/929/14/

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/929/15/ (handout)

PROGRAM ORGANIZATION

The Integrated English Program or IEP is a two-year English language learning program for

freshmen and sophomore students of the English Department. It is organized into 4 semester-

length integrated English courses: IE Levels I, II, III; each level had a course in combined skills

(IE Core), listening (IE Active Listening), and Writing (IE Writing). The final semester of the

IEP consists of a student-selected seminar (IE Seminar) on a specialized area of content.

The courses are integrated in the sense that the IE Core course integrates the four skills. In

addition, all three courses, IE Core, IE Writing, and IE Active Listening, share themes and

attendant vocabulary. There are currently 300 freshmen and an almost equal number of

sophomores in the program. Students are “streamed” into classes based on their English ability.

They are tested by the ITP, or Institutional Testing Program, a simplified version of the TOEFL

test with reading, grammar, and vocabulary sections available through the Educational Testing

Service. Accordingly, students are placed in levels I, II, and III of the program.

IE Core is taught in a weekly 180-minute class. On another day, there is the 90-minute IE

Active Listening course and a 90-minute IE Writing course. The grade for each student at the

end of the term is based on the following formula: 40% for IE Core; 30% for IE Active Listening,

and 30% for IE Writing.

There are two other IE courses, Academic Skills, and Academic Writing which students take in

their sophomore year. Academic Skills develops students’ listening and note-taking skills

through having them listen to several lectures by professors in the English Department.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

13

IE Core (180 min)

IE Writing (90 min)

IE Active Listening (90 min)

IE I

* Memories and

Childhood

* Urban Life

* Food

* Travel

IE II

* Changing Times

* The Workplace

* Geography

* Autobiography

IE III

* Psychology

* Cross-cultural

Values

* Environment

* The Media

IE Seminars

* Communications

* Linguistics

* Literature

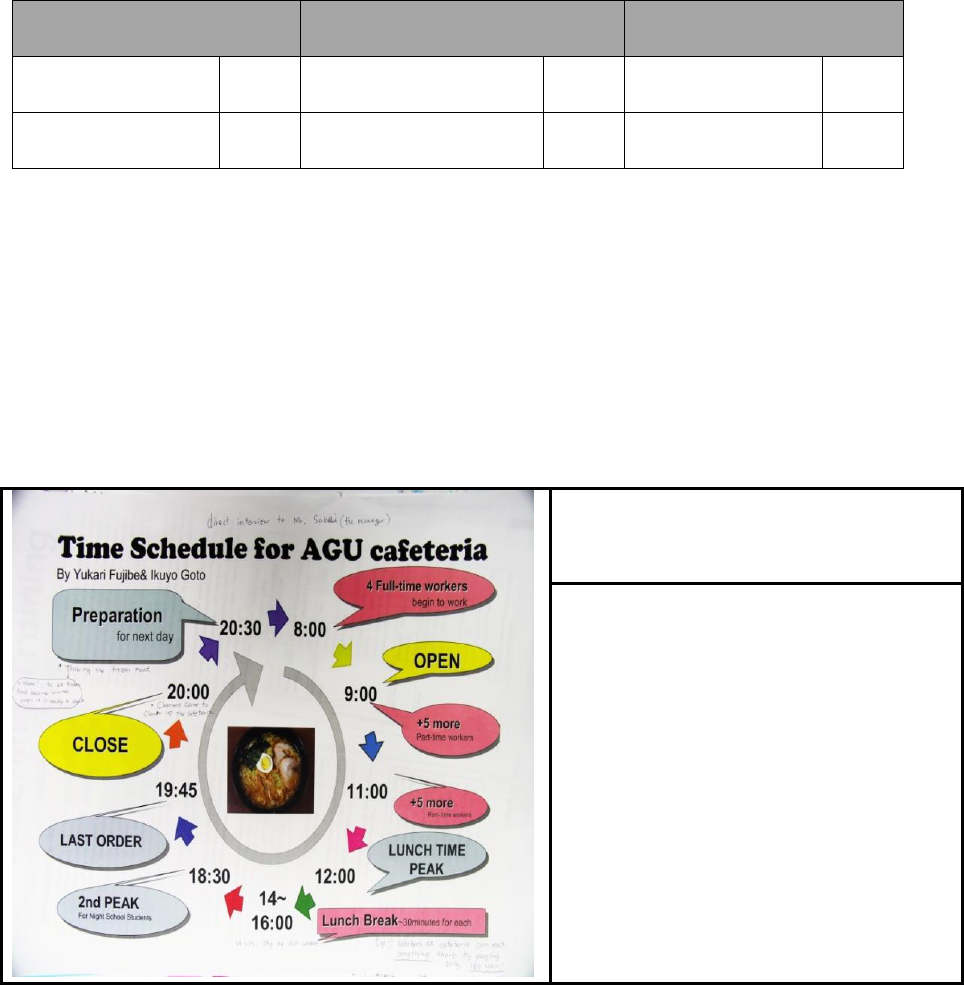

Figure1: The IE Courses and the themes at each level.

IE Writing I, II, III cover writing English paragraphs and writing essays with quotations and a

short bibliography. Academic Writing teaches students how to conduct original research and to

write a long paper.

IE Writing I

IE Writing II

IE Writing III

Academic Writing

Writing 3 paragraphs

of 150 words:

1. Classification

2. Comparison-

Contrast

3. Persuasive

Introduction to the

Essay: 2 essays of

350 words:

1. Comparison-

Contrast

2. Analysis

Review the Essay:

APA Style for quotes

and references in 2

essays of 350 words:

1. Classification

2. Persuasive

The Research Essay

of 1,500 words:

1. Creating a

bibliography

2. Citing references

in the APA style

Fig 2: IE Writing and the Academic Writing course

The IE courses are taught by approximately 3 full-time faculty, 35 part-time native speakers, and

17 part-time Japanese teachers. At the end of each semester, students evaluate the teachers.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

14

III. A PROGRAM SNAPSHOT

• A student who enters at level I and completes the IEP will participate in some 36 small group

discussions and lead about 9 of them.

• The same student will read 6 novels, write an analysis of each one, and describe each novel to

other students in a small group. Altogether, he or she will read more than 200,000 words;

some students much more than that

• He or she will learn a variety of reading strategies and be introduced to various genres of

literature.

• He or she will draft, revise, and complete 4 essays of about 350 words, and upon finishing

Academic Writing, one of 1,500 words.

• The same student will have many hours of guided listening and received instruction in

listening strategies.

Published research on the Academic Skills program suggests that students show significant

improvement in their comprehension and note-taking abilities. Likewise, experimental data on

the discussions in the IE Core classes shows significant increases in communication and

confidence in using English, and significant increases in vocabulary.

IV. PROFESSIONAL RESOURCES

The teacher resource area is in a small room beside in the English Department office, 9F,

Goucher Building (03-3409-8111).

There are teachers’ mailboxes, a small professional library of professional texts available for 2

week-loan, a collection of themed DVDs and videos (also available for loan), the teachers’

editions of Interchange 2, Interchange 3, and Interactions 2, additional copies of the student

booklets, and course book CD roms, and a DVD player and a CV player, both for previewing

materials for class. Additional materials for Academic Skills and IE Active Listening may be

found in the CALL teachers’ room, 6F, Goucher building. Many videotapes and DVDs are in the

Foreign Language Lab media library, Building 9, 1F.

In the main English Department area, there are journals and newspapers which you may read.

None of them may be taken from the room, however. The copier cannot be used in this area

because of accounting procedures that require you to use the copiers in the koushi hikae shitsu

(teachers’ rooms), buildings 8 and 1, 1F. In these teachers’ rooms are also PC computers with

Internet access and shelves for teachers to store their materials.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

15

You may arrange with the Language Laboratory, Goucher Building, 6F for your students to

borrow cameras and to use video editing equipment. Be aware that prior booking is needed for

this and for use of their editing facilities.

There are pre-service orientations for new teachers, an annual program symposium and

orientation in April, as well as lunchtime meetings at the end of each semester and as required.

Adjunct faculty also are added to an electronic ‘mailing list’ on Google Groups for program

information and upcoming vacancies for teaching classes.

Some 3,500 graded readers for student self-access, and to be used for Core book reports, can be

found on the first floor of the library building. They are to the right of the entrance turnstiles.

Teachers are all issued a school ID card which allows you to open the AV equipment cabinets in

each classroom, and to enter the university library. Teachers may also publish in the department

journal, Thought Currents, after joining the English Literary society for a nominal fee (2,000

yen). Limited parking spaces for cars and bicycles are available on campus.

IV.(a) ONLINE RESOURCES

In addition to the books that you can borrow on your library card, you also will have access to

journal articles through the AGU Library database of electronic resources. Feel free to use the

database for your private research and please familiarize yourself with it.

To use the database, follow these steps:

a) Go to AGU Library’s home page: http://www.agulin.aoyama.ac.jp/ . Click on English to the

far right of the toolbar (underneath MyLibrary). Of course, you can keep the site in Japanese

for use with your students.

Fig. 3: The Library and Aurora-Opac

Once you have clicked and the site is now in English, slide to the bottom of the page and

click on Database. Once it comes up, try searching for the Educational Resources

Information Center (ERIC), JSTOR, Proquest, or the Wiley Online Library.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

16

Each of these will provide access to many articles which you may use in your own research

or for class use.

Fig 4: A list of the library’s services and databases.

Typing any of these services into the Search part of the database will enable you to find articles,

usually as PDFs.

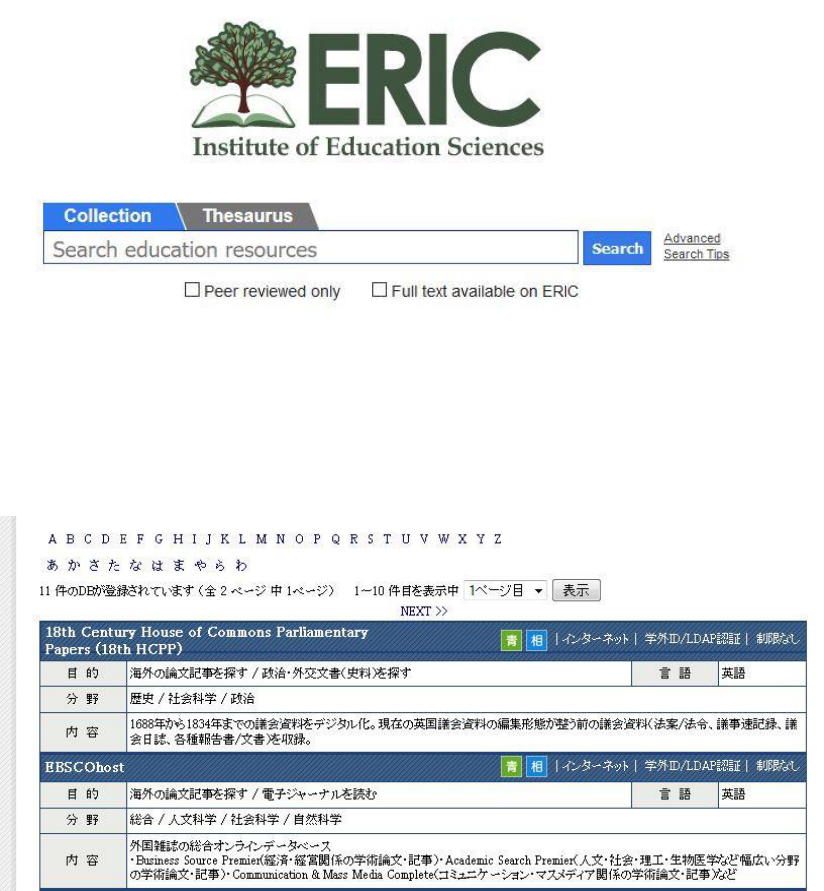

Fig. 5: Database of journals

The search will connect you with the ERIC home page and you will be able to access some of its

huge collection of articles on education.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

17

Fig. 6: Education Resources Information Center

You can access the host databases for EBSCO, and JSTOR by clicking on E or J the alphabet list

on the database (See the earlier screenshot) and then scrolling down to the database.

EBSCO host is here.

Fig. 7: EBSCO

JSTOR is shown next.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

18

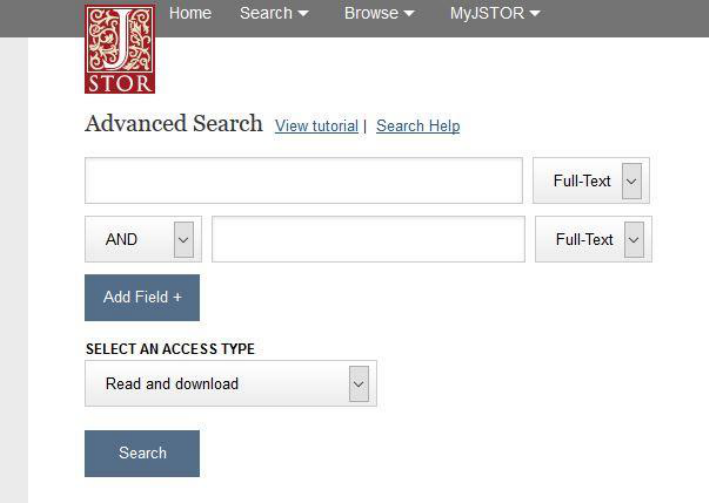

Fig. 8: JSTOR

b) You’ll find the following searchable databese especially useful:

* Academic Research Library (part of ProQuest)

* Communication & Mass Media Complete (part of EBSCOhost)

* Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts

* OED online

* TESOL Quarterly (only available at the Shibuya Campus) [With the exception

of the TESOL Quarterly, the journals are available from your home computer.]

c) After you click on a journal, you will be prompted for your user ID and password. Your user

name is your faculty ID number preceded by t00…

Fig 9: Log in

EBSCO, ERIC, and JSTOR all have simple searches and more advanced ones that enable you to

provide “search parameters” dialogue boxes into which you must type search terms.

The one for JSTOR looks like this:

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

19

Fig 10: Search Parameters

Using “and” and specifying a time period for the article to have appeared are different ways of

narrowing your search. The more specific and focused your search term, the better your search.

Some of the articles are available in their entirety. If the entire article can be accessed, you will

see「PDF」or 「HTML」under it. Clicking on those links will download the article. Please

help your students to distinguish between reliable and less trustworthy sources.

V. GRADING STUDENTS

Because students receive a final IE grade averaged of scores from their IE Core, IE Active

Listening, and IE Writing sections, each instructor must provide a precise numerical score for

each student. For example, you should assign a score of 73 rather than rounding the Fig to 70.

The weight for each of the IE courses is as follows: 40% for IE Core; 30% for IE Active

Listening, and 30% for IE Writing. We owe our students as accurate grading as possible, so

please use grading software to tally your grades as much as possible.

Finally, it should be possible for students to achieve a score of 90% or higher in any course of

the IEP. However, very few students in any class should be awarded such a high mark. Students

attaining such distinction should have made effort and achievements superior to almost every

other student in the class. Conversely, you should always have a few students that achieve an AA

score of 90% or higher, even in an IE I Core or IE I Writing course.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

20

Table 1 shows a sample distribution of grades for an IE I or IE II Core class. It is meant as a

guide to practice and teachers may adjust it. However, please note that categories such as

participation should not be more than 5% unless you specify exactly what constitutes that score.

Table 1: Sample IE I and II Core Grades

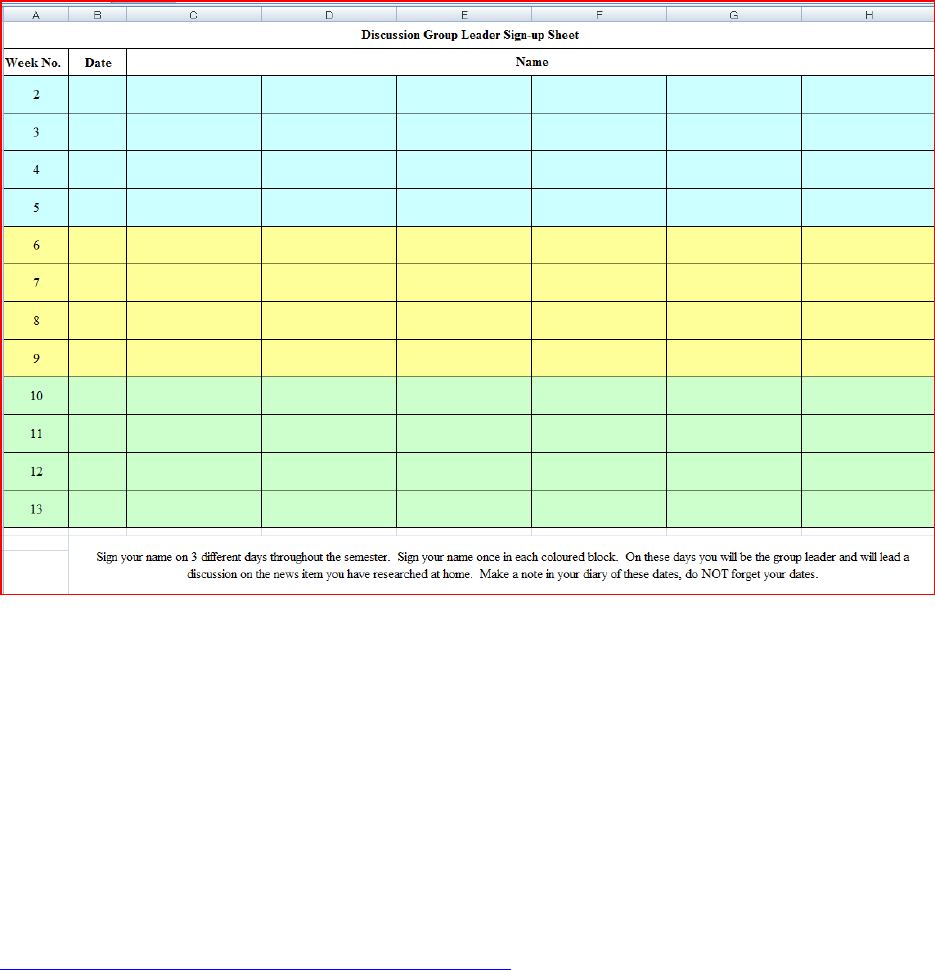

1) Discussion Leader – lead 3 discussions over the term, and

submitted the discussion summary and questions

25%

2) Journal or blog – student made several entries per week

and commented on another student’s journal or blog

20%

3) Extensive reading – a student’s effort to read digital

readers over the term

20%

4) 2 Book reports – a student reports on two books and

describes them to other students in class

25%

5) Homework – a student’s efforts at doing assigned work

from Interchange 2 or other assignments

5%

6) Participation – this relates to student readiness for class,

their effort in discussions, their preparedness, and activity

5%

V.(a) ON ATTENDANCE, LATES, AND GRADING

In the first class, students should be warned about regularly attending classes and coming to class

on time. Five or more absences without a doctor’s note, or attendance to a funeral and a student

fails the course. Three late arrivals of 30 minutes or more count as an absence. Please warn

students of this policy, and on a single absence or late, make sure that the student realizes the

consequences. Please be pro-active and try to curb this behaviour immediately as it is usually ne

or two students who will consistently miss classes or come late. Do not accept train certificates

every class from the same student. They should be making allowances for a train that is usually

late. Also, please make sure that the other students in the class are aware that latecomers are

losing points and having their grades adversely affected, and that you are unhappy with those

students and appreciative of those who are coming to class on time.

Student personal information should be handled with great discretion and their privacy should be

protected. However, collect your students’ contact telephone numbers and email addresses, or

better still, ask your students to e-mail you, perhaps with a question about the course or about

yourself. Once they have e-mailed you, it’s easy to set up a class e-mail list to remind students of

deadlines or even to post material to them. And there are two even more effective methods to

keep in touch with students now, LINE, through which can you text message individuals as well

as whole classes, and course power, the university-wide system of notifying students through the

portal as well as uploading your class materials so that students can access them easily outside of

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

21

class time. English manuals on the use of CoursePower are available on the AGU portal. Using

any of these means will make it easy for you to contact students who begin to show a pattern of

tardiness and absences.

Absences

Maximum Grade

1

*No effect on Grade

2

Final grade cannot be above 89%

3

Final grade cannot be above 79%

4

Final grade cannot be above 69%

5 or more

Fail

Fig 11: Policy on Absences and Grades

Again. Warn students early if they start missing classes. Please use your discretion when

presented with student excuses. Serious illnesses with a doctor’s note, or a family-related matter

such as a funeral, are acceptable. Otherwise, students forfeit points from their final grade.

Finally, do not hold up a class because a student who may be leading a discussion is late. There

have been complaints about teachers who wait for students to arrive before starting a class. Carry

on with other activities and do not punish the other students by wasting their time.

V.(b) GRADING SOFTWARE

Grading software provides the most efficient and accurate means of providing an accurate grade

for each student and record-keeping of these grades. Grading software enables a teacher to easily

calculate class averages, and to adjust scoring to better reflect a fair distribution of marks. Secondly, the

university requires teachers to keep their students’ grade for a five-year period in case of claims or other

needs, and it is easier to keep records on computer.

Some teachers in the IE Program use Excel spreadsheets to calculate grades. Others are using

apps such as Teacher Kit or iDoceo. Software such as iDoceo enables teachers to pair student photos

with names, set up groups, and perform grading operations.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

22

Fig 12: iDoceo grading and classroom management software

Fig 13: TeacherKit Classroom Manager

To use any kind of grading software, you will first have to load the students’ names and other

identifying information into the program.

You can find and download PDFs or CSV files of the rosters of all your classes on the Aogaku

Portal: https://aoyama-portal.aoyama.ac.jp/ . You can also find the portal by using the search

term “aogaku portal” in Google.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

23

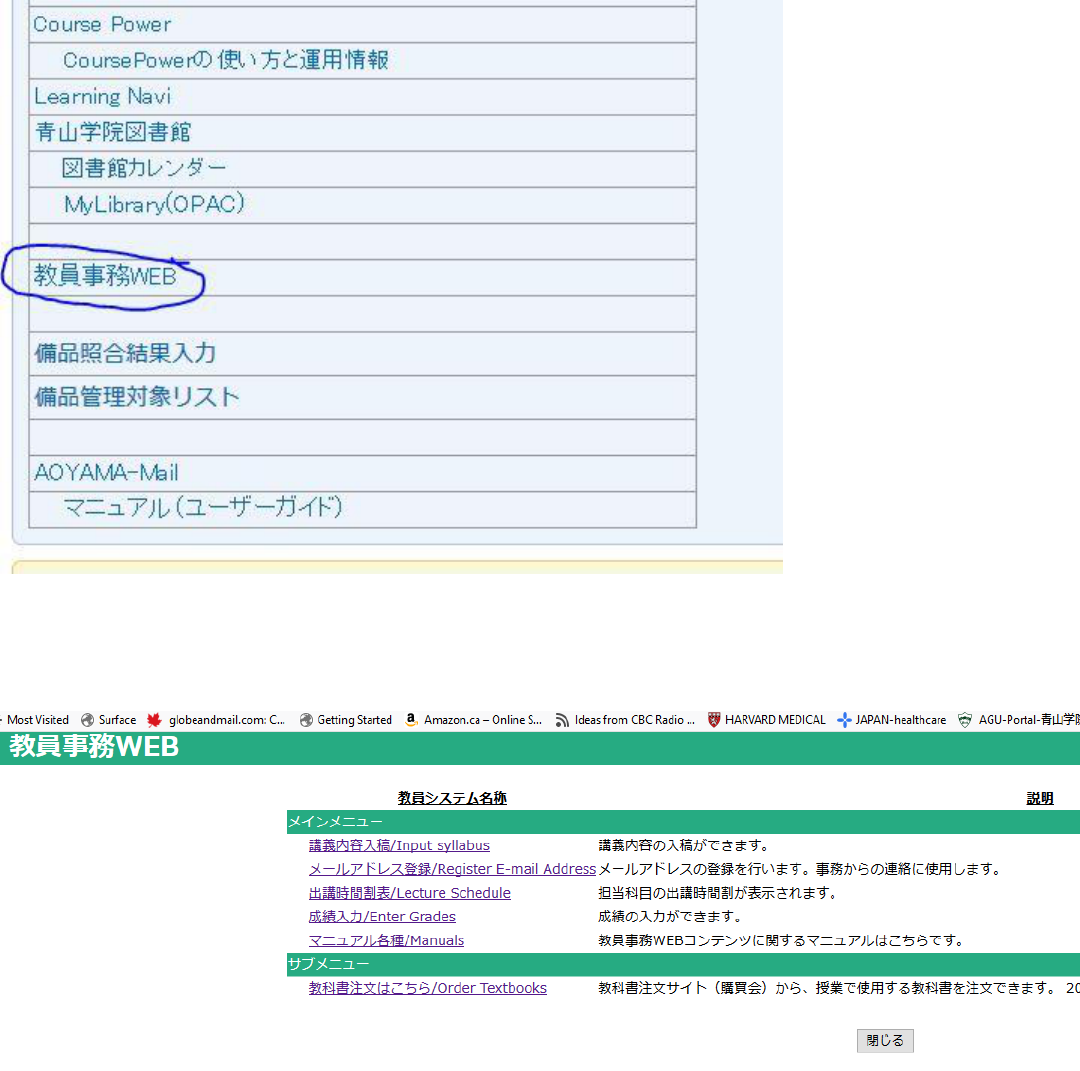

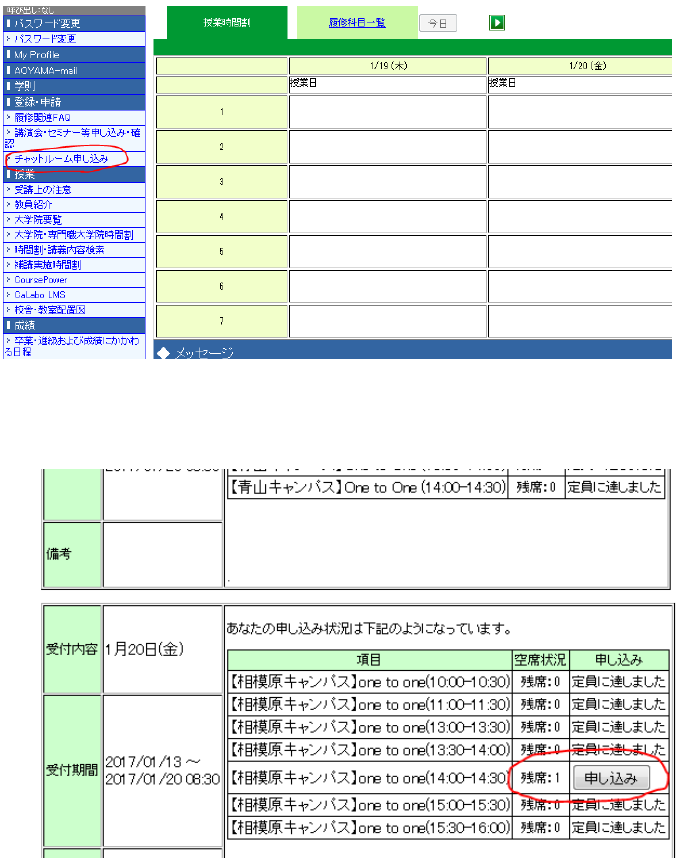

Instructions for logging onto the portal (refer to the images on the following page):

Enter your username (the number on your university identity card) into the field marked "ログイン ID".

The first digit of the number on your university identity card must be converted to a lowercase t. For

example, if the number on your university identity card is 000392, the number you should enter into the

field marked "ログイン ID" is t00392.

- Enter your LDAP password into the field marked "LDAP パスワード".

- Enter the numbers from the matrix based on the pattern you registered with the PC

Support Lounge.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

24

5. A page will open. Click on the 2

nd

item (“System”) on the menu.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

25

5. Scroll down the page to “Kyoin Web.

6. Clicking on this item will take you to your personal page where you can enter your

room requirements for the academic year, order your textbooks, download the students in

each of your courses, and enter your final grades for the course. Perhaps most importantly,

there are downloadable English manuals for using the system.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

26

A long menu of options appears. Go down the menu to the kyoin web (This is

the same procedure you use for posting grades, and choosing a classroom).

Fig. 14: A List of Options

A personalized list of options will appear. (Please note that the list includes English manuals for

how to input grades, and syllabi). Choose “download class lists.”

All your classes will appear.

Fig. 15: Teachers’ Course List

Click the button beside the class for which you wish to get a list of students:

You will be offered your class files organized by students’ numbers and in either PDF or CSV

formats. Export that CSV file for class (CSV 形式 クラス番号順) onto the desktop of your

computer.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

27

Fig. 16: PDF and CSV Files

You can open the CSV file in Excel.

1) Open the Excel CSV file. You may wish to delete the Japanese versions of students’ names

and everything else except the student numbers and names.

Fig. 17: List of students’ names written in kanji and romaji.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

28

Fig. 18: Edited listing of students’ names and numbers in a form that can be imported by grading

software.

V.(c) STUDENT PLAGIARISM

Student plagiarism is a problem in the English Department, elsewhere in the university, and

everywhere in higher education. The new IE Core and Writing booklet contains a warning about

plagiarism on the back of the table of contents. We are developing a database of past

assignments in order to check these against current ones. In your first class with your students,

please remind them of the penalties for plagiarism which are “failing the first assignment” (no

rewrites) and upon the second instance, “failing the entire course.” It’s important that your

students are made aware of this penalty in case you have to fail a student because of plagiarism.

In addition, please demonstrate to your students how easy it is to catch student plagiarism

through Google searches, and inappropriate word choice.

Equally important is that you provide students with alternatives to plagiarism and that you help

them to better manage their time on their assignments, so that they do not try to do everything at

the last moment, and in desperation, plagiarize from the Internet or from another student.

In terms of teacher administration and student time management, please get your students to

choose their 1

st

book by the third class in the semester, at the very latest.

When your students bring their books to class, have them write down their choices on a paper

that you circulate. Please file the paper. Ask them to choose their 2nd book and bring it class

while you are collecting their first reports.

A student who is unable to produce the book that he or she is going to read, or suddenly switches

books for the written report will be a red flag for plagiarism. This “book check" will force

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

29

students to start reading their books earlier, so there will be less temptation to cheat. Further

activities in class such as requiring students to bring their books to class to read from them for

ten or fifteen minutes, and then discuss what they have read will encourage students to work on

their book report over several weeks, and prevent any last minute cheating.

VI. LANGUAGE LEARNING TASKS

Researchers in Second Language Acquisition have proposed that grammatical or functional

language teaching syllabuses become more task-based. We have identified several key language

learning tasks at each level of the IEP: (a)small group work, (b)writing a journal, (c)reading 2

novels, (d)analyzing the 2 novels, (e)reporting on them to a small group. These tasks involve

small group work, so for maximum effectiveness at each of the three levels, teachers must ensure

that students participate in all discussions in English. Again, research has shown the

effectiveness of small group work.

But it must be managed in English with teacher supervision and student incentives in terms of

extra marks, student learning contracts, and so on. Additional tasks are found at the IE II and IE

III levels. Samples are printed in the IE Core and Writing student booklet.

Differences between the performances of IE I, II, III small group discussion groups are shown on

the IEP DVD. Similar differences should be noted between the written summaries and

evaluations at each of the three levels of the program.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

30

Fig 19: Common IE Tasks

COMMON IE I, II, III TASKS

Small Group Work

1. Use English to participate in pair and small group activities in speaking,

listening, reading, writing.

2. Learn how to read and listen to authentic audio and video materials.

Participate in a Weekly Discussion

3. Read and summarize news events, using the APA Style, identify key vocabulary.

4. Lead a small group discussion on news stories and explain the vocabulary.

5. Participate in weekly news discussions.

Write a Journal

6. Maintain a weekly journal in a notebook, blog, or message board.

7. Communicate with (a) partner(s).

8. Describe feelings, explain ideas and narrate events to another person.

(IE I and IE II) Extensive Reading (E.R.)

9. Learn how to read fluently.

10. Acquire new vocabulary.

Read 2 Novels

11. Take an interest in discussing books.

12. Verbalize feelings and impressions about literature.

Report on the 2 Novels

13. Using the APA style, note the author, title, place of publication, publisher, and the year.

14. Describe the book using the literary terms: setting, point of view, conflict, climax, symbol,

irony, theme.

15. Summarize the events.

16. Express an opinion about the book.

17. Draw upon your personal experiences to respond to the book

18. Give an oral report to classmates.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

31

Fig 20: IE III Tasks

Fig 21: IE Core Classes: Language Learning Tasks

IE III (Choose One)

A. Presentation

Use a theme to develop a presentation based

on a survey, or a fieldtrip.

1. Brainstorm survey items.

2. Determine subjects.

3. Ask survey questions.

4. Collate the answers.

5. Negotiate duties of group members.

6. Prepare an outline and create graphs and charts.

B. Making a PSA or Commercial

Develop and film a PSA or commercial.

Alternately, create a photo storyboard, a

photo montage/collage, or art book.

1. List potential products and services.

2. Choose the product.

3. Plan the commercial using storyboards and a

shooting script.

4. Depict different characters and create realistic

dialogue.

5. Use persuasive language to promote products

or services.

IE CORE I, II, III DISCUSSION TASK

I. Discussion Leader Preparation for a Media Discussion

1. Finds an English news item from a newspaper either in print or online.

2. Notes the author, and publisher in the APA style format.

3. Does some note-taking on it: an analysis of it, noting what, when, where, who,

why, and how.

4. Uses these notes to write the summary (Avoids copying from the original

news article).

5. Writes a statement of opinion.

6. Records key vocabulary which is new to the student.

8. Prepares three discussion questions.

II. In Class Small Group Discussion

1. Introduces self; learn/ use the names of others.

2. Makes eye contact and use gestures to communicate.

3. Paraphrases the news story to your partners without reading your paper.

4. Solicits opinions and agree or disagree and give reasons.

5. Interrupts others politely.

6. Asks clarification, provide follow-up questions.

7. Summarizes his/her partners’ points, noting these to describe them to the

rest of the class.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

32

* Forming student groups of 3 instead of 4 cuts the time needed for discussions and book reports.

It also encourages greater student participation.

VII. KEEPING A JOURNAL

We require IE Core teachers to use written journals, taped journals, or blogs with their classes as

the “free writing” component of the IE Core Section. Journals are for students to describe their

feelings, experiences, and ideas. Research on emerging student writing indicates how useful his

task can be in improving writing.

The chief objection instructors have toward journal writing is that it takes too much of their time

to respond to students. Our solution to this problem is to ask you to use "secret friends" or

penpals in your class. Rather than the teacher responding to each student, the students in a class

exchange journals with one another. Over the term, pairs of students write to each other using

“secret names.” These secrets and the students’ interest in guessing one another’s identity adds

excitement and even more immediacy to exchange of journals. The students reveal their

identities to one other in the last class.

Of course, you must give your students a clear explanation of what you expect of them in journal

writing and provide them with models. An early, effective way to do this is take in all their

journals after the first week, responding to them all with comments and in the following class,

sharing the best of these journals with the rest of the class, by showing the page on the OHC and

reading aloud to your students, then commenting on what made the writing so good. Please keep

the identities of the students “secret” however to avoid embarrassing any students.

If students are writing paper journals, then by term’s end, each student should have written about

36 entries and about the same number of pages, roughly 18 in his/her journal, and another 18 in a

partner’s journal. Generally, we ask students to write the equivalent of 3 double-spaced pages

each week.

Over the term, they should have written about 35 entries or pages over 13 weeks of the course.

Half of these entries will be in their notebook and the other half in their partner's. Make it clear

to students that, eventually, you will be reading the notebooks and their entries will Fig in their

final marks.

In the first class with your students, you might introduce journal writing by giving them 10

minutes to write their first journal entries of the semester. This is a good opportunity to

emphasize that the point of this activity is to improve their writing fluency and not to attain

grammatical accuracy. Some students will have great difficulty concentrating on their writing for

the whole ten minutes and in writing more than 50 words as well. You should write during this

time, too. That you have a benchmark of what you can do and what you might reasonably expect

from students writing for ten minutes.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

33

In the same class, you might show the class a simple word count formula where you count the

words in the first 3 lines of a journal entry, and divide by 3 to get the average number of words

per line. Multiplying this Fig by the number of lines in the journal entry, you will arrive at a

word count far more quickly than by counting each word as students do. List student scores on

the board as well as your own in order to emphasize this point. There probably will be a range

from 40 to 240 words. Putting the scores on the board encourages students to concentrate more

and to write faster.

The students should finish the other two journal entries at home during the following week. In

the second week, you should collect all the journals to see how the students are doing, assign

them an initial rank of High, Medium, or Low. Then, according to their interests and

personalities, match "secret friends" together. In the next class, read a few of the “better” journal

entries to let the class know your expectations. Then, assign the "secret friends.”

You maintain the secrecy of the students' partners and increase student excitement by requiring

everyone in your class to purchase the same style and colour of notebook. Preferably, this should

be an inexpensive one such as the B-5 size (250cm x 18cm) Campus notebook available in the

school bookstore for about 100 yen. You should bring a notebook to the first class to show the

students exactly what to purchase.

Each student chooses a secret name. The student writes that secret name on the inside cover of

his/her book. You should find out each student's secret name and record it on a journal checklist.

An easy way to manage the exchange of the journals and to keep their anonymity is a "mail bag."

At the beginning of class, students put their journals into the bag. At some point in class, the

teacher checks them off on the class checklist. Then the teacher passes the bag to a student in

class who looks for his/her partner's journal in the bag. From that student, the mail bag circulates

to the other students.

With this approach, you only read the students' journals once after the first week of classes. You

do this to set your standards for the activity. As mentioned earlier, read aloud some of the better

entries (carefully concealing the students’ identities) in the second week, and show them on the

OHC. Through the rest of the term, students will receive regular, detailed responses to their

writing from their secret partners.

Typically, a number of students will hand in journals that are a few lines less than the 3 page

double-spaced, or 1.5 page single-spaced requirement. It is very important to catch them cutting

corners on the assignment early on. Point out to them that their entries are too short and that they

might have got a higher mark if they had been of the right length or longer.

Then collect all the journals again on the second-to-last class. This will allow you to return the

journals to the students and enable them to read your comments.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

34

They can also meet and talk with their secret partners before the end of the classes. Otherwise, if

you leave the journals to be picked up after classes end, some students forget to pick them up.

When you take in the journals, you also provide a detailed written response on at least one page.

You should describe what you liked reading. You might grade their work with three simple

categories: unsatisfactory, satisfactory, outstanding (minus-check, check, check-plus signs).

VII.(a) EMAIL EXCHANGE

As an alternative to exchanging notebook journals, you may wish to set up a blog or LMS forum

for students in your class to participate on. The exchange might even include students in another

IE class. This would be particularly effective in IE III since students will have already done

journals in IE I and IE II. The parameters of the activity would be very similar to those for print-

based journals. Students would be required to make about three entries each week. They might

use "pen names" to add interest to the activity.

VII.(b) ONLINE JOURNALS (BLOGGING)

These days, a number of IE teachers use a blog for their class journals. Blogs are online diaries in

which the blogger can be anonymous or reveal his/her identity. Students can post ‘comments’ on

each others’ blogs after reading them. It is just as important with this approach to set clear

expectations and to provide students with examples of desirable entries and ‘comments.’

Blogger.com (maintained by Google) is a very popular blogging platform and has a

straightforward interface.

This approach encourages greater computer literacy and a stronger identification of the class as a

group. Blogs also provide a semi-permanent and public forum for writing. All of these aspects

promote purposeful student communication through writing. Finally, blogging imparts an

interesting twist on journal writing, especially for IE III Core students, many of whom may have

used a paper journal in their IE I and IE II Core classes.

VIII. XREADING: IE I & IE II CORE

There are a number of reasons why we are using Xreading. First of all, Xreading will enable us

to introduce extensive reading or ER into the IEP and research indicates that ER can improve

students’ vocabulary, and, possibly, their reading speed, reading comprehension, and knowledge

of grammatical structures.

Secondly, the program offers the convenience to students in signing out books through mobile

devices which they can access any place and at any time – for example, last year, many of our

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

35

students read on the train. Next, Xreading has a very powerful learning management system

(LMS) that enables teachers to easily track how many words, and how many books that a student

is reading, so we can get our students to do more reading without having the burden of reading

and grading more book reports. Finally, there are some aspects of the program such as the

student ratings and suggested titles that will help a student find more to read in their area of

interest and according to their reading ability and motivate them to read more widely in English.

These features will help us to encourage as many students as possible to read more than 200,000

words in one year. That number has been identified as the turning point in students’ abilities.

Fig 22: Xreading website

Introducing Xreading:

Before starting with the Xreading program with your students, explain its rationale. It is a means

of them learning English grammar and vocabulary and improving their reading skills. It also

helps their fluency and reading speed. In class, try a few minutes of uninterrupted silent reading

before any longer assignments. Go over the reading menu with students to make sure that they

understand how to operate it and can choose books appropriately. Explain to them that they need

to take the multiple choice test and that they rate the book when finished reading it, to ensure that

they gain credit for it.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

36

VIII.(b) STUDENT ONBOARDING

As the university has a site license to use Xreading, it will not be necessary for students to

purchase a subscription for Xreading. Make that very clear to students because if they purchase a

subscription online, it will be difficult for them to get a refund.

The student onboarding process is entirely taken care of by the program coordinators, so teachers

need not “create classes” on the Xreading website or add students to them.

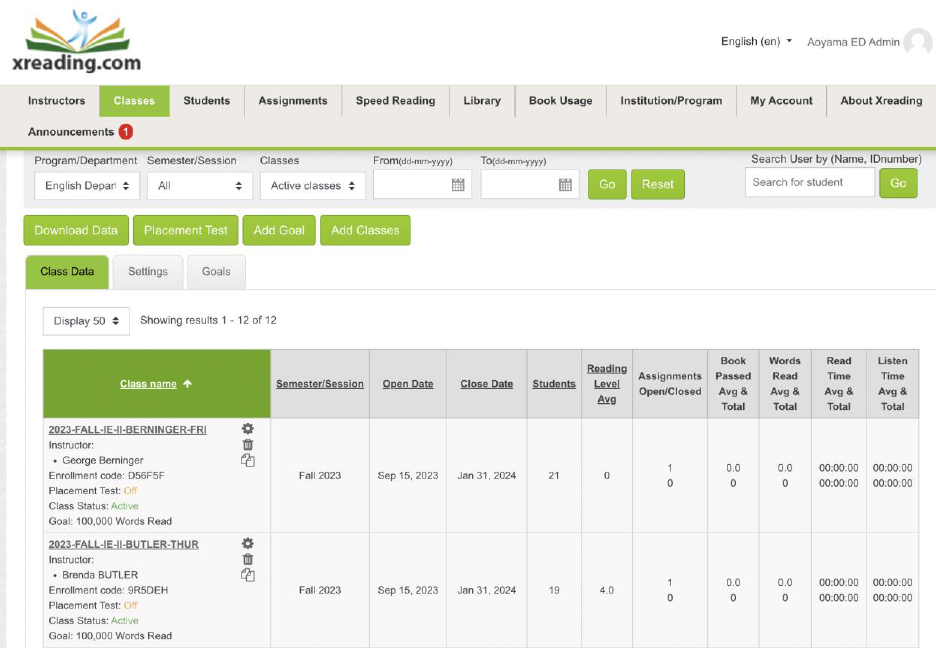

Fig 23: Teachers will be able to find their class by clicking on the “Classes” tab.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

37

VIII.(c) XREADING: CREATING A CLASS

Once you have logged into the Xreading.com site, you will see your class. (Class rosters are

available early in the semester and they are used by program coordinators to create Xreading

class groupings. Students in the IEP have been tested using either the Institutional TOEFL

placement test or a TOEIC test that serves the same purpose. Their reading scores suggest that

they should be able to read books with a headword count of between 1501 and 2100.

Fig 24: Various categories of information about the students’ reading practice can be accessed by

teachers, including the number of books read, the average reading level and speed, and the

quizzes passed.

In the past we eliminated the graded readers from Levels 1 to 8 because it was thought they

would be too easy for the students, but, in the interest of giving students maximum choice we no

longer restrict the available texts by headwords. However, we do put restrictions on the students’

ability to select books similar to those they already read since it would be a simple matter for

them to pass the subsequent tests even if they had not read another version of the work.

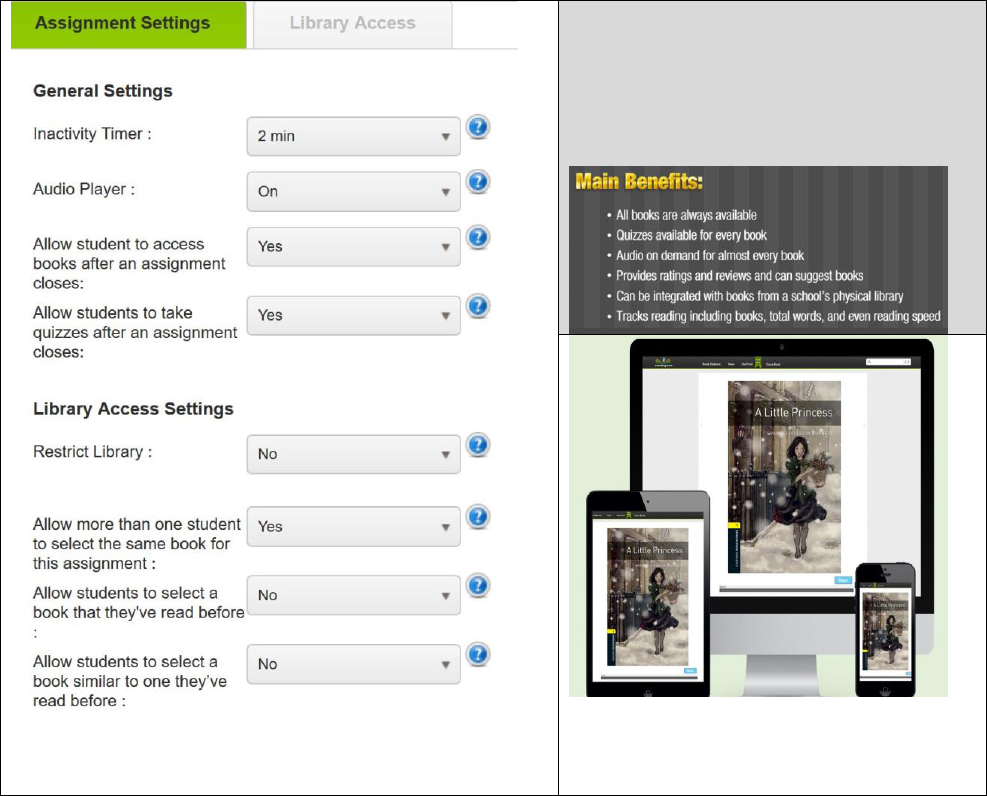

Fig 25: Settings for Each Class and List of Publishers of the Readers

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

38

In Fig 26, you can see another feature, “inactivity” which means that if a student doesn’t swipe

his phone or tablet to turn the page, the system will become inactive.

Other features that can be activated or tweaked include the audio player (which, when enabled,

allows students to listen to the book being read), and setting that call prohibit students from

reading the same book (if there were concern about students “collaborating” on tests).

Fig 26: Assignment Settings and Viewing a Graded Reader on Multiple Devices

VIII.(d) READING LEVELS, READING SPEEDS

The following chart in Fig 33 is an overview of reading levels

(http://erfoundation.org/wordpress/graded-readers/erf-graded-reader-scale/).

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

39

The levels on the scale were made by an analysis of hundreds of graded readers. It ranges from

scarcely knowing the alphabet to near-native ability (ie. 18,000 headwords).

Fig 27: ERF Grading Scale.

In the 1

st

class, you should have your students try reading a few books at different levels in order

to find the appropriate level for them. The chart will help them as well because when using a

graded reader, a student should be able to comprehend almost every word on the page. Some

researchers put the figure anywhere from 95% to 98%.

As they read, they should ask themselves these questions.

• Can I read it without a dictionary?

• Am I reading it quickly?

• Do I understand almost everything? (Over 95%)

If the answer is “Yes” to each of these questions, then that book is their level or they could try a

higher level. If the answer is no to even one of the questions, then they should go down levels

until they have 3 “Yes” answers.

A very conservative estimate of their reading speed is that each student should be able to read a

minimum of 100 words per minute at present. If they are reading more than 180 words per

minute, please speak to the student and check the book they were and their language ability.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

40

In our pilot study with Xreading we found that a few students were choosing very low levels of

books and of stories that they already knew, fairy tales, or novels based on films in order to boost

their total number of words read.

VIII.(e) ACCESSING XREADING: TABLETS, PCs

Surveys of our students last term suggested that some students were concerned about streaming

digital graded readers and their data plans. Please inform them that a download of this type, of

words does not take more than few yen of their plan. Data usage is high for making phone calls

and for watching lengthy videos.

Once students have an Xreading account and provided that they download the app, they can

access their books anywhere and on any device – a tablet, a PC or Mac, in addition to their

mobile phones. Please advise students of this as some students may wish to read on other devices

and may even bring a tablet or laptop to class for reading.

VIII.(f) WEEKLY BOOK TALKS

Following the methodology in our pilot study, we are setting aside 15 minutes of class time for

IE Core I and II students to read followed by 15 minutes for discussion with a partner. We also

expect students to do an additional 45 minutes of reading for homework. Altogether, students

should be reading about 6,000 words per week and able to achieve some 80,000 words over the

term. However, as this is the first term that we are using Xreading with all our IE Core I and

Core II students, we are setting modest goals that we hope most students can achieve for a grade

of 80%, ie. in IE I Core, 60,000 words, and a higher amount in IE II Core, 70,000 words. (Please

see Table 2).

Before the reading and the book talks begin, you should give the students a weekly update on

how the class is doing. Try to obscure the names of individual students, but show the progress of

students in the class.

During the reading period, make the rounds in your class to make sure that students are logging

on correctly and that they are able to choose a book. Also, you will need to check to make sure

that the students are focused on the task and not texting or reading e-mails. Afterward, you might

try to do some reading online yourself to model reading for your students.

During the discussion period, you should use the time to offer encouragement to your students

and to liaise briefly with students who are failing to meet the weekly reading quotas. Just letting

students know that you are watching their progress will encourage them to do more reading.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

41

Once the 15 minutes has finished, use a projector to display the potential questions about a

reading. Give the students a few minutes to choose their questions.

I. RESPONDING TO THE PLOT (Without telling the ending of the book):

a) If you were a character in the story, what would you do differently?

b) If you were the author, what would you change in the book?

c) Is there a character especially inspiring, depressing or even frightening? Explain why.

d) Which incidents in the novel did you find wonderful, surprising, comical, or even shocking?

f) Are there any parts of the plot that you found too predictable or unbelievable? Why?

g) How did what you expect to happen in the book compare with what actually happened?

II. REFLECTING ON THE STORY (Without telling the ending of the book):

a) How does the character’s life compare to your own?

b) How does the environment in the story compare to that in your own country?

c) If the book has been made into a film, how would you compare the film with the book?

d) If you have read another of the author’s books, how does this one compare?

e) How does this book compare to books with a similar theme?

f) Do you agree or disagree with the author’s view of people and life? Support your opinion.

h) What is something you learned from the story?

i) Have you changed your ideas about anything after reading this book?

Fig 28: Discussion Topics

VIII.(g) STUDENT CREDIT FOR BOOKS

Students get credit after they have finished each book by taking a four-item multiple choice test.

They will not get credit for a book unless they take the test. If they forget to take the test, it will

be hard for them to write the test later. You will need to go into the menu for your class and

change the setting to allow the student to take the test.

Additionally, you should ask your students to rate each book that they read. This is a second

measure to ensure that students are reading each book and doing so carefully. It can also become

part of their discussions with their classmates.

Table 2 shows how many words students need to read by the end of the term in order to achieve

a certain score for this part of their IE course. Please note that there is a difference of 10,000

words between IE Core I and IE Core II to reflect our higher expectations for students in that

course. To achieve each grade, students must have completed the number of words and done the

quiz for each book and done a rating for each book.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

42

If a student has missed a rating for a book, for example, then please deduct some points from the

student’s final score. For other intermediate scores, for example, an IE I Core student who reads

65,000 words and has done the quizzes and the ratings, should get 85%, and one who reads

45,000 words get 65%.

Similarly, an IE II Core student who reads 75,000 words will get 85% and one who only reads

35,000 words will get 45%. Most of your students will be using a paperback for their book report.

Please make a note of how many words are in the book. Have the students record the word

count when they do their reports as well.

Table 2: Assessing Student Reading

IE I Core

IE Core II

80,000 words

70,000

60,000 words

50,000

40,000 words

30,000

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

90,000 words

80,000

70,000 words

60,000

50,000 words

40,000

30,000 words

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

VIII.(h) XREADING SCHEDULE

Xreading is a new technology that will take time to introduce into your class. In the first class,

some students, perhaps most students will not have purchased their access cards. Students will

have difficulties in properly logging onto the website. The instructions are on the student access

card, however, in the first class, perhaps two, there will be some difficulties. It will help if you

pair students who have logged on with others still trying to get onto the site.

Other challenges will include showing students how the menu works and how to choose an

appropriate book that is not too easy or hard for them to read. One effective way to handle this is

to add a student account for yourself to your class. That way you can show them a “student

screen” which will be different than your own screen.

Another important strategy is to take your students to the graded reader section of the university

library in the last 20 minutes at the end of your first or second period. This is in the basement

floor near the wall. Show your students different levels of books and explain the head word idea

to them. As well, have them choose a paperback for use for their book report.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

43

They can also use this book for the first class or two if they have forgotten to buy their Xreading

access card. Should the server go down in class, students can also refer to their paperback.

1

st

class

a) Explain the benefits of extensive reading: learning new vocabulary, improving

reading speed, and comprehension, even learning grammar and writing structures.

b) Explain that students will receive marks for how many words they read over the

semester.

c) Show the students the teachers’ interface (or show the illustration in this guide) so

that they understand how you can read their data

d) Show them Xreading on your phone, ideally a dummy student account that you

create for the class.

e) Have the students access Xreading on their phones by following the instructions on

the back of their access cards.

f) Possibly introduce a graded reader to your students by reading part of it aloud for 5-

10 minutes (students follow on their phones), then stopping and noting the time.

g) Explain how students will regularly read 15 minutes in class and then talk about their

readings. Give students their first reading period and then follow it with a discussion.

Tell students to read at least 45 minutes more outside of class.

2nd class

a) Show students the class progress to date (carefully hiding the names of individual

students). Explain to students how your learning management system (LMS) works

b) Possibly read more of the graded reader from the previous week to students with

them following along. The remainder of this book could be assigned to your students to

finish reading for credit.

c) Start the 15 minute reading period and during this time assist students who are having

trouble logging on. Carry on to the book talks.

3rd class

a) By now, all students should have accessed their accounts and been able to read online

and 15 minutes of reading and 15 minutes of discussion should be a regular feature of

the class.

b) Introduce a new feature of Xreading, the listening function whereby each book can

be listened to, and demonstrate this in class. Encourage students to try it and offer them

the option of listening and reading or even listening to a book.

c) Encourage students to choose a paperback from the library to read for their book

reports. Explain the difficulty of using a digital format for this. Allow students to

choose a paperback format of a digital reader if they wish.

SCOPE AND SEQUENCE

44

4th class and others

a) Show the class ranking in terms of students’ reading totals.

b) Carry on with the 15 minutes of reading and 15 minutes of discussion. During the

discussion period, liaise with individual students who are falling behind and try to

encourage them to read more.

Fig 29: Xreading Schedule

VIII.(i) ADDITIONAL ER ACTIVITIES IN CLASS

Xreading is the means by which we are introducing extensive reading into the IEP. However,

there are other activities to promote reading fluency that can be introduced into your class. These

are drawn from the many suggestions from Paul Nation’s What Should Every ESL Teacher Know

1. Best recordings of student reading a passage – students record a paragraph from their reader

and play it to a partner; then play it to a group; choose the best, share with the class.

2. Repeated oral reading where students try reading the same text 3 times, faster each time.

3. Students all read the same text and then write down summaries of what they’ve read after

intervals of 5 minutes- 4 minutes – 3 minutes- 2 minutes – 1 minute. They compare their results.

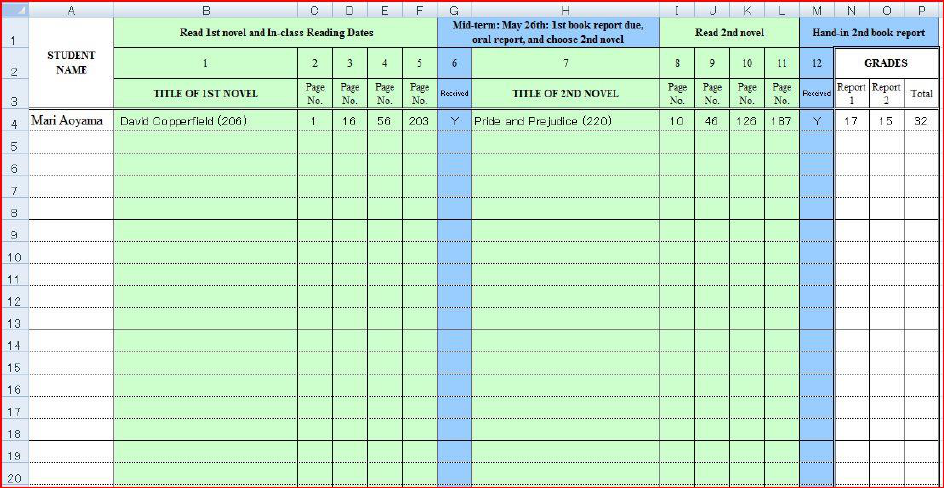

IX. READING 2 NOVELS

Students read two books over the term to develop their fluency and their ability to analyze

literature. Afterward, they will write an analysis of the use of literary terms in each book, a

response to the novel, and a summary of the action.

Additional activities might include each student maintaining a “reading journal” of