Atom Counting (Chemical Formula Notations)

Looking At How Chemical Formulas Are Written

Instructions: For each of the following chemical reactions identify the number of atoms of

each element. The following pages give you some help counting items.

4 FeS + 7 O

2

→ 2 Fe

2

O

3

+ 4 SO

2

Fe = 4 Fe = (2x2) = 4

S = 4 S = 4

O = 7x2 = 14 O = (2x3) =6, O = (4x2) = 8 6+8 = 14

PCl

5

+ 4 H

2

O → H

3

PO

4

+ 5 HCl

4 NH

3

+ 5 O

2

→ 4 NO + 6 H

2

O

TiCl

4

+ 2 H

2

O → TiO

2

+ 4 HCl

C

2

H

6

O + 3 O

2

→ 2 CO

2

+ 3 H

2

O

2 Fe + 6 HC

2

H

3

O

2

→ 2 Fe(C

2

H

3

O

2

)

3

+ 3 H

2

3 CaCl

2

+ 2 Na

3

PO

4

→ Ca

3

(PO

4

)

2

+ 6 NaCl

3 Hg(OH)

2

+ 2 H

3

PO

4

→ Hg

3

(PO

4

)

2

+ 6 H

2

O

Subscripts

We use subscripts in chemical formulae to indicate the number of atoms of an element present in am

molecule or formula unit. There are no exceptions to this. Here are some examples:

The familiar formula of water is a good place to start. It indicates that each water molecule contains

two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen. In terms of atoms, water always has a 2:1 ratio of hydrogen to

oxygen.

Note also that if no subscript is written, we assume it to be one.

While there are plenty of naming rules in the field of chemistry (they fill books), many chemical

compounds like water and many of the ones to follow have common names. We almost never refer to

water as "dihydrogen oxide."

Methane is one of the simplest hydrocarbons (a compound containing only carbon and hydrogen).

These are important as fuels. Methane is a major component in natural gas.

Sulfuric acid is a strong acid you'll learn about in the section on acids and bases. It's one of the more

commonly-used acids in research and industry.

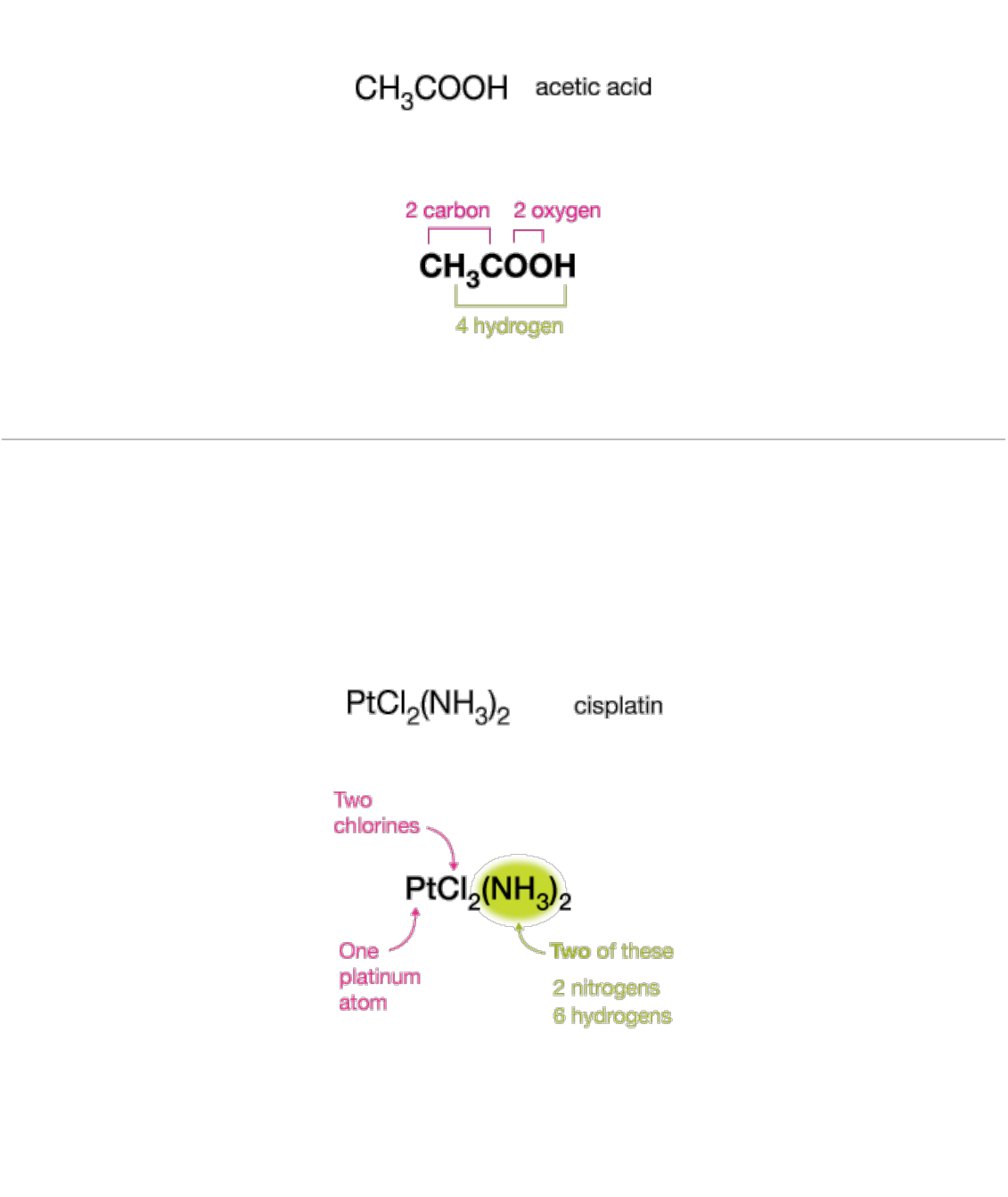

Some formulas contain more than one instance of a single element. There are some good reasons

for this that you'll learn in time. One example is acetic acid:

We follow exactly the same rules for counting atoms in these kinds of formulae, we just need to add

up all instances of a given atom.

Parentheses

Very often in chemical formulae, we use parentheses to form subgroups of atoms within a molecule.

Usually this has some meaning about the structure of the molecule, but don't worry about that for

now.

Parentheses are useless in a chemical formula if they don't have a subscript, so we'll assume one is

always there. In such a formula, the subscript outside the parentheses means that to count atoms,

you must multiply that subscript by the numbers of atoms inside.

Here's an example. Cisplatin is an important drug used in chemotherapy, and it's written like this:

Here's how we count the atoms in that formula.

The NH

3

in parentheses, known as an amine group, occurs twice. The 2 outside the parentheses is

multiplied by the implied subscript of 1 on the nitrogen, for a total of two nitrogens, and by the

subscript of 3 on the hydrogen for a total of six hydrogens.

Here's a rough picture of the structure of cisplatin. You can see why we group those NH

3

's. Amine

groups appear in a wide variety of compounds, so you'll see them again.

Here are a few more examples of the use of parentheses in chemical formulas.

It turns out that iron can come in two different "flavors," iron (II) and iron (III). It can also form the

compounds FeSO

4

and Fe

3

(SO

4

)

3

. Here's how we calculate the numbers of atoms in this molecule:

There are 13 total atoms in this compound of copper, they are:

Coefficients

Very often in chemistry we attach numerical coefficients to the front of a chemical formula. We do this

mainly when we balancechemical equations, which is how we make sure that the law of conservation

of matter(matter can neither be created nor destroyed) is followed.

Here's a simple example

This notation means "two water molecules." The 2 simply doubles everything. Although we never

write them, parentheses around the molecule, H

2

O in this case, are always implied.

Now it's easy to see that the coefficient is used like a multiplier outside of parentheses. The 2

multiplies all of the subscripts (even the 1's that aren't written) inside of the parentheses:

So in two water molecules, there are a total of four hydrogen atoms and two oxygens. Easy-peasy.

Here's another example, one in which the molecular formula contains parentheses.

The first thing to do is to ignore the coefficient and tackle the parentheses:

Now we can add up the H's and O's, add in the iron and multiply everything by the coefficient, 8.

We always work these problems from the inside outward. Begin with the innermost parentheses,

working outward. The coefficient is last, and we treat it as though there are parentheses around the

whole molecule.