Preserving America’s Heritage

ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION

Protecting Historic Properties:

A CITIZEN’S GUIDE TO

SECTION 106 REVIEW

g

p

p

P

rotectin

g

Historic

P

ro

p

ertie

s

WWW.ACHP.GOV

Protecting Historic Properties 1

e mission of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

(ACHP) is to promote the preservation, enhancement, and

productive use of the nation’s historic resources and advise the

President and Congress on national historic preservation policy.

e ACHP, an independent federal agency, also provides a

forum for infl uencing federal activities, programs, and policies

that aff ect historic properties. In addition, the ACHP has a key

role in carrying out the Preserve America program.

e 23-member council is supported by a professional staff in

Washington, D.C. For more information contact:

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 803

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 606-8503

www.achp.gov

CONTENTS

4 What is Section 106 Review?

5 Understanding Section 106 Review

8 Determining Federal Involvement

12 Working with Federal Agencies

14 Infl uencing Project Outcomes

18 How the ACHP Can Help

20 When Agencies Don’t Follow the Rules

21 Following Through

22 Contact Information

About the ACHP

COVER PHOTOS:

Clockwise, from top left: Historic Downtown Louisville,

Kentucky; Section 106 consultation at Medicine Lake,

California; bighorn sheep petroglyph in Nine Mile Canyon,

Utah (photo courtesy Jerry D. Spangler); Worthington

Farm, Monocacy Battlefi eld National Historic Landmark,

Maryland (photo courtesy Maryland State Highway

Administration).

2 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 3

Proud of your heritage? Value the places that refl ect your

community’s history? You should know about Section 106

review, an important tool you can use to infl uence federal

decisions regarding historic properties. By law, you have a voice

when a project involving federal action, approval, or funding

may aff ect properties that qualify for the National Register of

Historic Places, the nation’s offi cial list of historic properties.

is guide from the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

(ACHP), the agency charged with historic preservation

leadership within federal government, explains how your voice

can be heard.

Each year, the federal government is involved with many projects

that aff ect historic properties. For example, the Federal Highway

Administration works with states on road improvements, the

Department of Housing and Urban Development grants funds

to cities to rebuild communities, and the General Services

Administration builds and leases federal offi ce space.

Agencies like the Forest Service, the National Park Service, the

Bureau of Land Management, the Department of Veterans

Aff airs, and the Department of Defense make decisions daily

Introduction

Dust from vehicles may

affect historic sites in

Nine Mile Canyon, Utah.

(photo courtesy Jerry D.

Spangler, Colorado Plateau

Archaeological Alliance)

about the management of federal buildings, parks, forests, and

lands. ese decisions may aff ect historic properties, including

those that are of traditional religious and cultural signifi cance

to federally recognized Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian

organizations.

Projects with less obvious federal involvement can also

have repercussions on historic properties. For example, the

construction of a boat dock or a housing development that

aff ects wetlands may also impact fragile archaeological sites and

require a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers permit. Likewise, the

construction of a cellular tower may require a license from the

Federal Communications Commission and might compromise

historic or culturally signifi cant landscapes or properties

valued by Indian tribes or Native Hawaiian organizations for

traditional religious and cultural practices.

ese and other projects with federal involvement can harm

historic properties. e Section 106 review process gives you

the opportunity to alert the federal government to the historic

properties you value and infl uence decisions about projects that

aff ect them.

Public Involvement

M

atters

4 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 5

In the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA),

Congress established a comprehensive program to preserve

the historical and cultural foundations of the nation as a

living part of community life. Section 106 of the NHPA is

crucial to that program because it requires consideration of

historic preservation in the multitude of projects with federal

involvement that take place across the nation every day.

Section 106 requires federal agencies to consider the eff ects of

projects they carry out, approve, or fund on historic properties.

Additionally, federal agencies must provide the ACHP an

opportunity to comment on such projects prior to the agency’s

decision on them.

Section 106 review encourages, but does not mandate,

preservation. Sometimes there is no way for a needed project to

proceed without harming historic properties. Section 106 review

does ensure that preservation values are factored into federal

agency planning and decisions. Because of Section 106, federal

agencies must assume responsibility for the consequences of the

projects they carry out, approve, or fund on historic properties

and be publicly accountable for their decisions.

What is Section 106 Review?

Regulations issued by the ACHP spell out the Section 106

review process, specifying actions federal agencies must take to

meet their legal obligations. e regulations are published in the

Code of Federal Regulations at 36 CFR Part 800, “Protection of

Historic Properties,” and can be found on the ACHP’s Web site

at

www.achp.gov.

Federal agencies are responsible for initiating Section 106 review,

most of which takes place between the agency and state and

tribal or Native Hawaiian organization offi cials. Appointed by

the governor, the State Historic Preservation Offi cer (SHPO)

coordinates the state’s historic preservation program and consults

with agencies during Section 106 review.

Agencies also consult with offi cials of federally recognized Indian

tribes when the projects have the potential to aff ect historic

properties on tribal lands or historic properties of signifi cance

to such tribes located off tribal lands. Some tribes have offi cially

designated Tribal Historic Preservation Offi cers (THPOs),

while others designate representatives to consult with agencies

as needed. In Hawaii, agencies consult with Native Hawaiian

organizations (NHOs) when historic properties of religious and

cultural signifi cance to them may be aff ected.

To successfully complete Section 106 review,

federal agencies must do the following:

gather information to decide which properties in the

area that may be aff ected by the project are listed, or are

eligible for listing, in the National Register of Historic

Places (referred to as “historic properties”);

determine how those historic properties might be aff ected;

explore measures to avoid or reduce harm (“adverse

eff ect”) to historic properties; and

reach agreement with the SHPO/THPO (and the

ACHP in some cases) on such measures to resolve any

adverse eff ects or, failing that, obtain advisory comments

from the ACHP, which are sent to the head of the agency.

Understanding

Section 106 Review

The National Soldiers Monument (1877) at Dayton

(Ohio) National Cemetery was cleaned and

conserved in 2009 as part of a program funded

by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

(photo courtesy Department of Veterans Affairs)

Conservation

6 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 7

What are Historic Properties?

In the Section 106 process, a historic property is a prehistoric

or historic district, site, building, structure, or object included

in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic

Places. is term includes artifacts, records, and remains

that are related to and located within these National Register

properties. e term also includes properties of traditional

religious and cultural importance to an Indian tribe or Native

Hawaiian organization, so long as that property also meets the

criteria for listing in the National Register.

e National Register of Historic Places

e National Register of Historic Places is the nation’s offi cial

list of properties recognized for their signifi cance in American

history, architecture, archaeology, engineering, and culture. It

is administered by the National Park Service, which is part of

the Department of the Interior. e Secretary of the Interior

has established the criteria for evaluating the eligibility of

properties for the National Register. In short, the property

must be signifi cant, be of a certain age, and have integrity:

Signifi cance . Is the property associated with events,

activities, or developments that were important in the

past? With the lives of people who were historically

important? With distinctive architectural history,

landscape history, or engineering achievements? Does it

have the potential to yield important information through

archaeological investigation about our past?

Age and Integrity . Is the property old enough to be

considered historic (generally at least 50 years old) and

does it still look much the way it did in the past?

During a Section 106 review, the federal agency evaluates

properties against the National Register criteria and seeks the

consensus of the SHPO/THPO/tribe regarding eligibility. A

historic property need not be formally listed in the National

Register in order to be considered under the Section 106

process. Simply coming to a consensus determination that a

property is eligible for listing is adequate to move forward with

Section 106 review. (For more information, visit the National

Register Web site at

www.cr.nps.gov/nr).

When historic properties may be harmed, Section 106 review

usually ends with a legally binding agreement that establishes

how the federal agency will avoid, minimize, or mitigate the

adverse eff ects. In the very few cases where this does not occur,

the ACHP issues advisory comments to the head of the agency

who must then consider these comments in making a fi nal

decision about whether the project will proceed.

Section 106 reviews ensure federal agencies fully consider

historic preservation issues and the views of the public during

project planning. Section 106 reviews do not mandate the

approval or denial of projects.

SECTION 106: WHAT IS AN

ADVERSE EFFECT?

If a project may alter characteristics that qualify a

specifi c property for inclusion in the National Register

in a manner that would diminish the integrity of

the property, that project is considered to have an

adverse effect. Integrity is the ability of a property to

convey its signifi cance, based on its location, design,

setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association.

Adverse effects can be direct or indirect and

include the following:

physical destruction or damage

alteration inconsistent with the Secretary of the

Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic

Properties

relocation of the property

change in the character of the property’s use or

setting

introduction of incompatible visual, atmospheric,

or audible elements

neglect and deterioration

transfer, lease, or sale of a historic property

out of federal control without adequate

preservation restrictions

8 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 9

If you are concerned about a proposed project and wondering

whether Section 106 applies, you should fi rst determine

whether the federal government is involved. Will a federal

agency fund or carry out the project? Is a federal permit,

license, or approval needed? Section 106 applies only if a

federal agency is carrying out the project, approving it, or

funding it, so confi rming federal involvement is critical.

Determining Federal

Involvement

IS THERE FEDERAL

INVOLVEMENT? CONSIDER

THE POSSIBILITIES:

Is a federally owned or federally controlled

property involved, such as a military base,

park, forest, offi ce building, post offi ce, or

courthouse?

Is the agency proposing a project on

its land, or would it have to provide a right-of-way

or other approval to a private company for a project

such as a pipeline or mine?

Is the project receiving federal funds,

grants, or loans?

If it is a transportation project,

frequent sources of funds are the Federal Highway

Administration, the Federal Transit Administration,

and the Federal Railroad Administration. Many

local government projects receive funds from the

Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency

provides funds for disaster relief.

Does the project require a federal permit,

license, or other approval?

Often housing

developments impact wetlands, so a U.S. Army

Corps of Engineers permit may be required. Airport

projects frequently require approvals from the

Federal Aviation Administration.

Many communications activities, including cellular

tower construction, are licensed by the Federal

Communications Commission. Hydropower and

pipeline development requires approval from the

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Creation of

new bank branches must be approved by the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation.

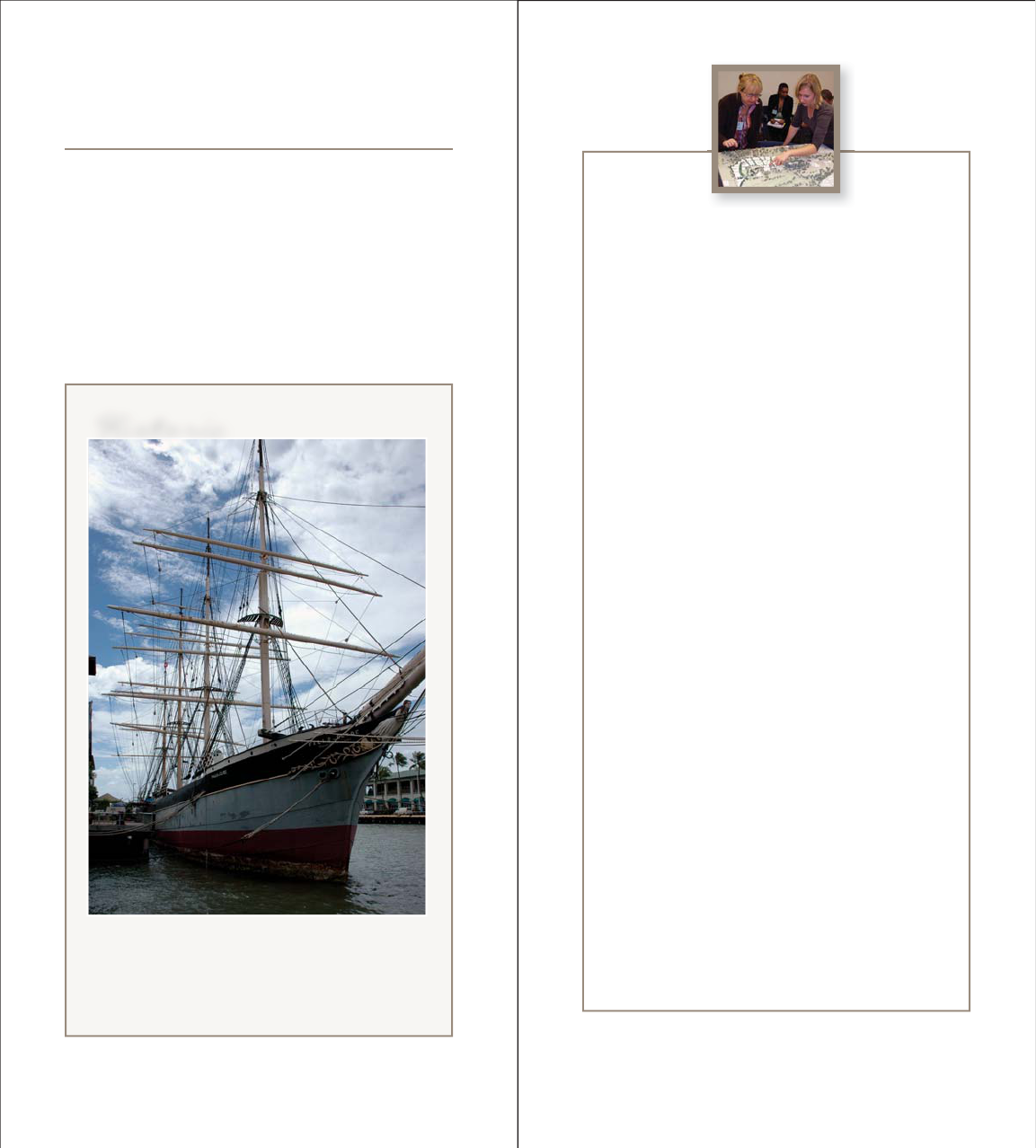

Falls of Clyde, in Honolulu, Hawaii, is the last surviving

iron-hulled, four-masted full rigged ship, and the only

remaining sail-driven oil tanker. (photo courtesy

Bishop Museum Maritime Center)

H

istoric

10 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 11

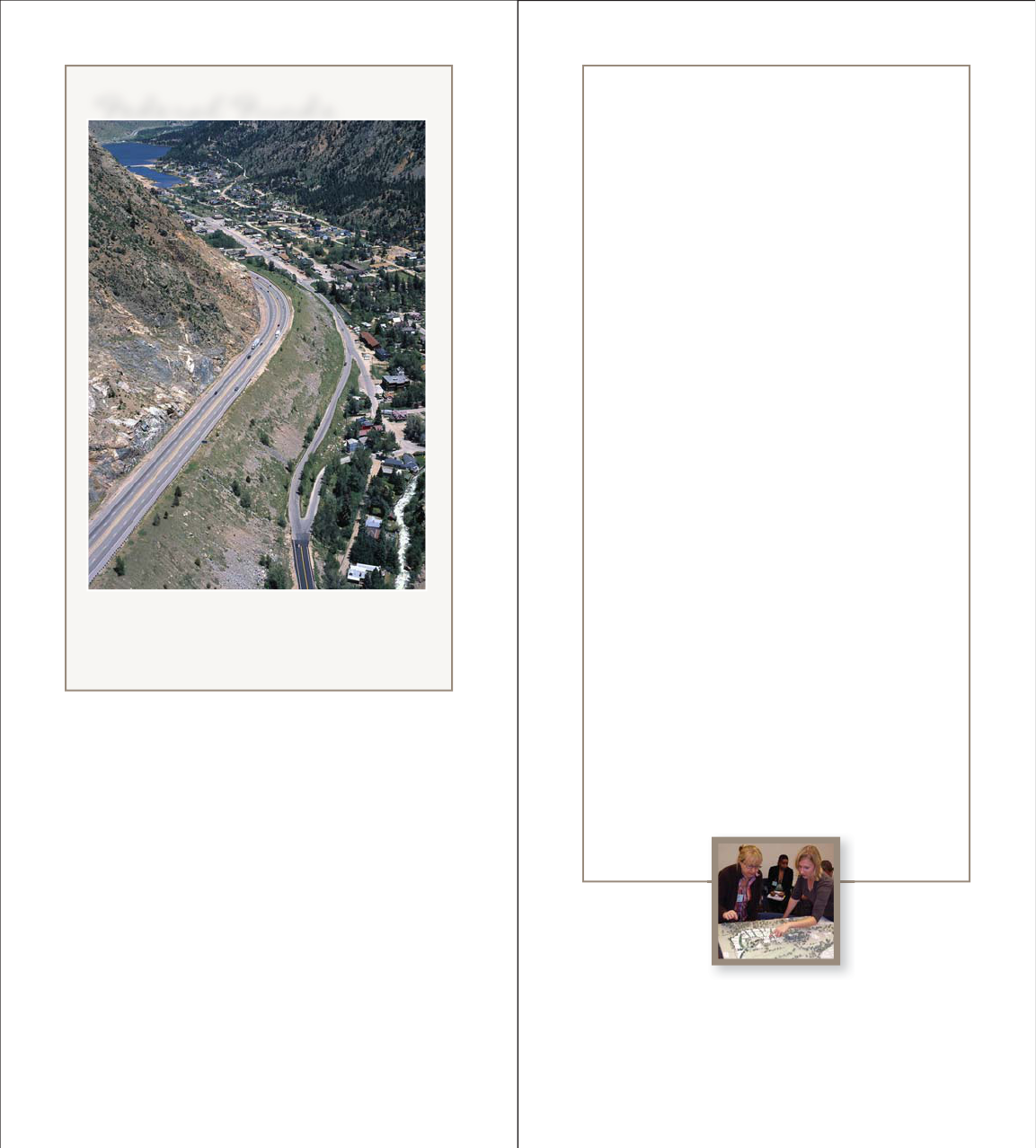

Interstate 70 at the Georgetown-Silver Plume

National Historic Landmark, Colorado (photo

courtesy J.F. Sato & Associates)

F

ederal

F

und

s

Sometimes federal involvement is obvious. Often, involvement

is not immediately apparent. If you have a question, contact the

project sponsor to obtain additional information and to inquire

about federal involvement. All federal agencies have Web sites.

Many list regional or local contacts and information on major

projects. e SHPO/THPO/tribe, state or local planning

commissions, or statewide historic preservation organizations

may also have project information.

Once you have identifi ed the responsible federal agency, write

to the agency to request a project description and inquire about

the status of project planning. Ask how the agency plans to

comply with Section 106, and voice your concerns. Keep the

SHPO/THPO/tribe advised of your interest and contacts

with the federal agency.

MONITORING FEDERAL

ACTIONS

The sooner you learn about proposed projects

with federal involvement, the greater your chance of

infl uencing the outcome of Section 106 review.

Learn more about the history of your neighborhood,

city, or state. Join a local or statewide preservation,

historical, or archaeological organization. These

organizations are often the ones fi rst contacted by

federal agencies when projects commence.

If there is a clearinghouse that distributes information

about local, state, tribal, and federal projects, make

sure you or your organization is on its mailing list.

Make the SHPO/THPO/tribe aware of your interest.

Become more involved in state and local decision

making. Ask about the applicability of Section 106 to

projects under state, tribal, or local review. Does your

state, tribe, or community have preservation laws in

place? If so, become knowledgeable about and active

in the implementation of these laws.

Review the local newspaper for notices about

projects being reviewed under other federal

statutes, especially the National Environmental

Policy Act (NEPA). Under NEPA, a federal agency

must determine if its proposed major actions will

signifi cantly impact the environment. Usually, if

an agency is preparing an Environmental Impact

Statement under NEPA, it must also complete a

Section 106 review for the project.

12 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 13

roughout the Section 106 review process, federal agencies

must consider the views of the public. is is particularly

important when an agency is trying to identify historic

properties that might be aff ected by a project and is considering

ways to avoid, minimize, or mitigate harm to them.

Agencies must give the public a chance to learn about the

project and provide their views. How agencies publicize

projects depends on the nature and complexity of the particular

project and the agency’s public involvement procedures.

Public meetings are often noted in local newspapers and on

television and radio. A daily government publication, the

Federal Register (available at many public libraries and online at

www.gpoaccess.gov/fr/index.html), has notices concerning

projects, including those being reviewed under NEPA. Federal

agencies often use NEPA for purposes of public outreach

under Section 106 review.

Federal agencies also frequently contact local museums and

historical societies directly to learn about historic properties

and community concerns. In addition, organizations like

the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) are

actively engaged in a number of Section 106 consultations on

projects around the country. e NTHP is a private, non-

profi t membership organization dedicated to saving historic

places and revitalizing America’s communities. Organizations

Working with Federal Agencies

like the NTHP and your state and local historical societies

and preservation interest groups can be valuable sources of

information. Let them know of your interest.

When the agency provides you with information, let the

agency know if you disagree with its fi ndings regarding what

properties are eligible for the National Register of Historic

Places or how the proposed project may aff ect them. Tell the

agency—in writing—about any important properties that you

think have been overlooked or incorrectly evaluated. Be sure to

provide documentation to support your views.

When the federal agency releases information about project

alternatives under consideration, make it aware of the options

you believe would be most benefi cial. To support alternatives

that would preserve historic properties, be prepared to discuss

costs and how well your preferred alternatives would meet

project needs. Sharing success stories about the treatment or

reuse of similar resources can also be helpful.

Applicants for federal assistance or permits, and their

consultants, often undertake research and analyses on behalf of

a federal agency. Be prepared to make your interests and views

known to them, as well. But remember the federal agency is

ultimately responsible for completing Section 106 review, so

make sure you also convey your concerns directly to it.

Hangar 1, a historic dirigible

hangar at Moffett Field at

NASA Ames Research

Center, California

L

earn About the

P

ro

j

ec

t

jj

j

14 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 15

In addition to seeking the views of the public, federal agencies

must actively consult with certain organizations and individuals

during review. is interactive consultation is at the heart of

Section 106 review.

Consultation does not mandate a specifi c outcome. Rather, it

is the process of seeking, discussing, and considering the views

of consulting parties about how project eff ects on historic

properties should be handled.

To infl uence project outcomes, you may work through the

consulting parties, particularly those who represent your

interests. For instance, if you live within the local jurisdiction

where a project is taking place, make sure to express your views

on historic preservation issues to the local government offi cials

who participate in consultation.

Infl uencing Project Outcomes

You or your organization may want to take a more active

role in Section 106 review, especially if you have a legal or

economic interest in the project or the aff ected properties. You

might also have an interest in the eff ects of the project as an

individual, a business owner, or a member of a neighborhood

association, preservation group, or other organization. Under

these circumstances, you or your organization may write to the

federal agency asking to become a consulting party.

WHO ARE

CONSULTING PARTIES?

The following parties are entitled to participate as

consulting parties during Section 106 review:

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation;

State Historic Preservation Offi cers;

Federally recognized Indian tribes/THPOs;

Native Hawaiian organizations;

Local governments; and

Applicants for federal assistance, permits,

licenses, and other approvals.

Other individuals and organizations with a

demonstrated interest in the project may participate

in Section 106 review as consulting parties “due to

the nature of their legal or economic relation to the

undertaking or affected properties, or their concern

with the undertaking’s effects on historic properties.”

Their participation is subject to approval by the

responsible federal agency.

Residents in the Lower Mid-City Historic District

in New Orleans express their opinions about

the proposed acquisition and demolition of their

properties for the planned new Department of

Veterans Affairs and Louisiana State University

medical centers which would replace the facilities

damaged as a result of Hurricane Katrina.

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

pp

p

Sp

eak

Up

pp

16 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 17

When requesting consulting party status, explain in a letter to

the federal agency why you believe your participation would be

important to successful resolution. Since the SHPO/THPO

or tribe will assist the federal agency in deciding who will

participate in the consultation, be sure to provide the SHPO/

THPO or tribe with a copy of your letter. Make sure to

emphasize your relationship with the project and demonstrate

how your connection will inform the agency’s decision making.

If you are denied consulting party status, you may ask the

ACHP to review the denial and make recommendations to

the federal agency regarding your participation. However, the

federal agency makes the ultimate decision on the matter.

Consulting party status entitles you to share your views, receive

and review pertinent information, off er ideas, and consider

possible solutions together with the federal agency and other

consulting parties. It is up to you to decide how actively you

want to participate in consultation.

MAKING THE MOST OF

CONSULTATION

Consultation will vary depending on the federal

agency’s planning process and the nature of the project

and its effects.

Often consultation involves participants with a wide

variety of concerns and goals. While the focus of some

may be preservation, the focus of others may be time,

cost, and the purpose to be served by the project.

Effective consultation occurs when you:

keep an open mind;

state your interests clearly;

acknowledge that others have legitimate

interests, and seek to understand and

accommodate them;

consider a wide range of options;

identify shared goals and seek options that allow

mutual gain; and

bring forward solutions that meet the agency’s

needs.

Creative ideas about alternatives—not complaints—

are the hallmarks of effective consultation.

Section 106 consultation with an Indian tribe

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

G

Get Involved

G

18 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 19

Under Section 106 review, most harmful eff ects are addressed

successfully by the federal agency and the consulting parties

without participation by the ACHP. So, your fi rst points

of contact should always be the federal agency and/or the

SHPO/THPO.

When there is signifi cant public controversy, or if the

project will have substantial eff ects on important historic

properties, the ACHP may elect to participate directly in the

consultation. e ACHP may also get involved if important

policy questions are raised, procedural problems arise, or if

there are issues of concern to Indian tribes or Native Hawaiian

organizations.

Whether or not the ACHP becomes involved in consultation,

you may contact the ACHP to express your views or to request

guidance, advice, or technical assistance. Regardless of the

How the ACHP Can Help

scale of the project or the magnitude of its eff ects, the ACHP

is available to assist with dispute resolution and advise on the

Section 106 review process.

If you cannot resolve disagreements with the federal agency

regarding which historic properties are aff ected by a project

or how they will be impacted, contact the ACHP. e ACHP

may then advise the federal agency to reconsider its fi ndings.

CONTACTING THE ACHP:

A CHECKLIST

When you contact the ACHP, try to have the

following information available:

the name of the responsible federal agency and

how it is involved;

a description of the project;

the historic properties involved; and

a clear statement of your concerns about the

project and its effect on historic properties.

If you suspect federal involvement but have been

unable to verify it, or if you believe the federal agency

or one of the other participants in review has not

fulfi lled its responsibilities under the Section 106

regulations, you can ask the ACHP to investigate. In

either case, be as specifi c as possible.

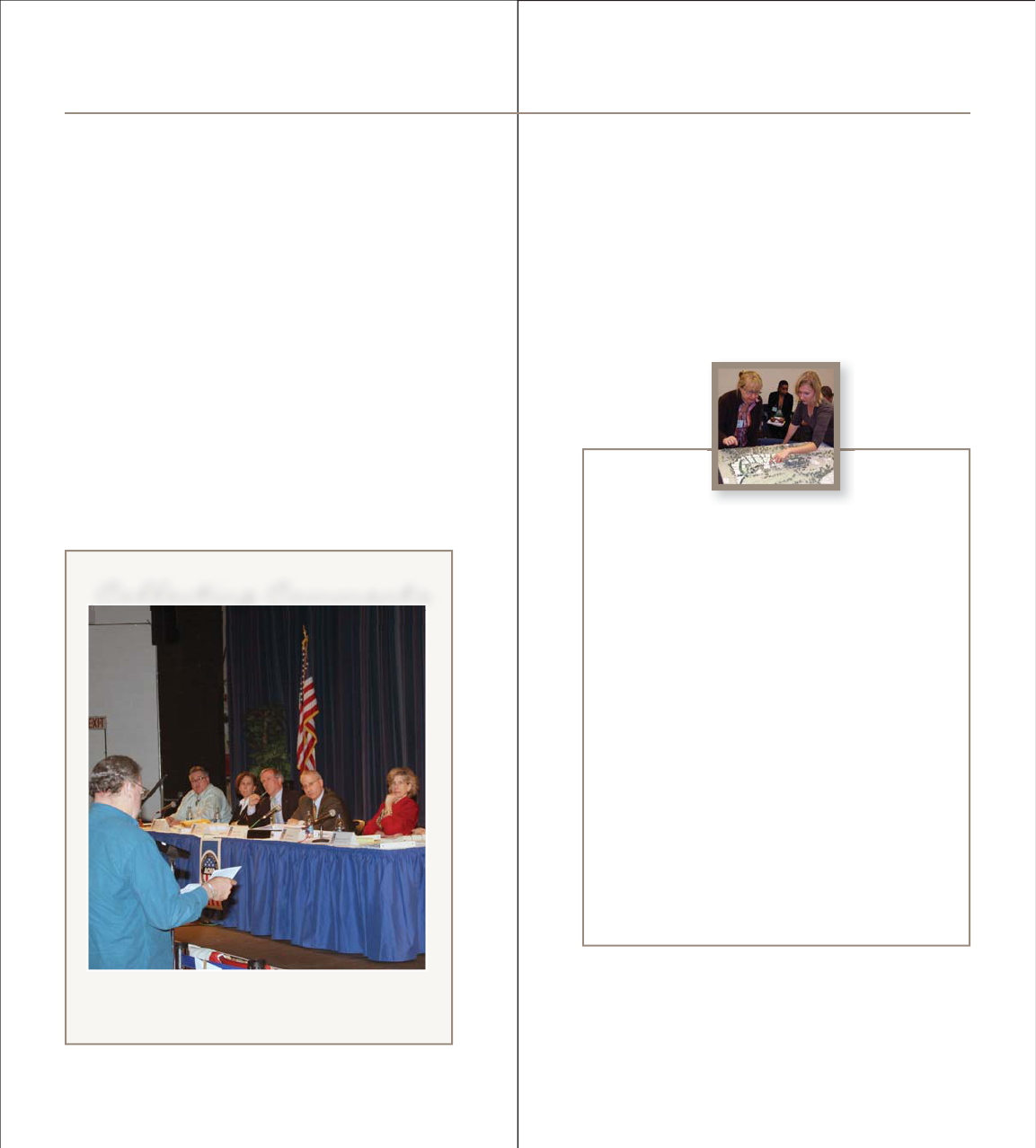

A panel of ACHP members listen to comments

during a public meeting.

Collecting Comments

g

g

g

g

g

g

g

20 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 21

A federal agency must conclude Section 106 review before

making a decision to approve a project, or fund or issue a

permit that may aff ect a historic property. Agencies should not

make obligations or take other actions that would preclude

consideration of the full range of alternatives to avoid or

minimize harm to historic properties before Section 106

review is complete.

If the agency acts without properly completing Section 106

review, the ACHP can issue a fi nding that the agency has

prevented meaningful review of the project. is means that,

in the ACHP’s opinion, the agency has failed to comply with

Section 106 and therefore has not met the requirements of

federal law.

A vigilant public helps ensure federal agencies comply fully

with Section 106. In response to requests, the ACHP can

investigate questionable actions and advise agencies to take

corrective action. As a last resort, preservation groups or

individuals can litigate in order to enforce Section 106.

If you are involved in a project and it seems to be getting off

track, contact the agency to voice your concern. Call the SHPO

or THPO to make sure they understand the issue. Call the

ACHP if you feel your concerns have not been heard.

When Agencies Don’t

Follow the Rules

After agreements are signed, the public may still play a role in

the Section 106 process by keeping abreast of the agreements

that were signed and making sure they are properly carried out.

e public may also request status reports from the agency.

Designed to accommodate project needs and historic values,

Section 106 review relies on strong public participation.

Section 106 review provides the public with an opportunity to

infl uence how projects with federal involvement aff ect historic

properties. By keeping informed of federal involvement,

participating in consultation, and knowing when and whom to

ask for help, you can play an active role in deciding the future of

historic properties in your community.

Section 106 review gives you a chance to weigh in when

projects with federal involvement may aff ect historic properties

you care about. Seize that chance, and make a diff erence!

Following rough

Milton Madison Bridge over the Ohio River between

Kentucky and Indiana (photo courtesy Wilbur Smith

Associates/Michael Baker Engineers)

S

ta

y

In

f

ormed

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

y

f

22 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 23

Contact Information

National Park Service

Heritage Preservation Services

1849 C Street, NW (2255)

Washington, D.C. 20240

E-mail: [email protected]

Web site: www.nps.gov/history/hps

National Register of Historic Places

1201 Eye Street, NW (2280)

Washington, D.C. 20005

Phone: (202) 354-2211

Fax: (202) 371-6447

E-mail: [email protected]

Web site: www.nps.gov/history/nr

National Trust for Historic Preservation

1785 Massachusetts Avenue, NW

Washington, D.C. 20036-2117

Phone: (800) 944-6847 or (202) 588-6000

Fax: (202) 588-6038

Web site: www.preservationnation.org

The National Trust has regional offi ces in San Francisco, Denver,

Fort Worth, Chicago, Boston, and Charleston, as well as fi eld

offi ces in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C.

Offi ce of Hawaiian Affairs

711 Kapi`olani Boulevard, Suite 500

Honolulu, HI 96813

Phone: (808) 594-1835

Fax: (808) 594-1865

E-mail: [email protected]g

Web site: www.oha.org

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

Offi ce of Federal Agency Programs

1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 803

Washington, D.C. 20004

Phone: (202) 606-8503

Fax: (202) 606-8647

E-mail: [email protected]

Web site: www.achp.gov

The ACHP’s Web site includes more information about working

with Section 106 and contact information for federal agencies,

SHPOs, and THPOs.

National Association of Tribal Historic

Preservation Offi cers

P.O. Box 19189

Washington, D.C. 20036-9189

Phone: (202) 628-8476

Fax: (202) 628-2241

E-mail: [email protected]

Web site: www.nathpo.org

National Conference of State Historic

Preservation Offi cers

444 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 342

Washington, D.C. 20001

Phone: (202) 624-5465

Fax: (202) 624-5419

Web site: www.ncshpo.org

For the SHPO in your state, see www.ncshpo.org/fi nd/index.htm

24 ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Protecting Historic Properties 25

Beneath the Sur

f

ac

e

ff

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

f

Ohio Department of Transportation

workers made an unanticipated

archaeological discovery while working just

north of Chillicothe along state Route 104.

It is a remnant of an Ohio & Erie Canal

viaduct. (photo courtesy Bruce W. Aument,

Staff Archaeologist, ODOT/Offi ce of

Environmental Services)

TO LEARN MORE

For detailed information about the ACHP, Section 106 review

process, and our other activities, visit us at www.achp.gov or

contact us at:

Advisory Council on Historic Preservation

1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 803

Washington, D.C. 20004

Phone: (202) 606-8503

Fax: (202) 606-8647

E-mail: [email protected]v

Preserving America’s Heritage

WWW.ACHP.GOV

Printed on paper made with an average of 100% recycled fi ber and

an average of 60% post-consumer waste