Council Special Report No. 70U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

Council on Foreign Relations

58 East 68th Street

New York, NY 10065

tel 212.434.9400

fax 212.434.9800

1777 F Street, NW

Washington, DC 20006

tel 202.509.8400

fax 202.509.8490

www.cfr.org

Cover Photo: Women study the Quran at

the Maska Road Islamic School in Kaduna,

Nigeria, on July 16, 2014. The school

condemns the violent ideology of Boko

Haram. (Joe Penney/Courtesy Reuters)

Council Special Report No. 70

November 2014

John Campbell

U.S. Policy to

Counter Nigeria’s

Boko Haram

U.S. Policy to Counter

Nigeria’s Boko Haram

Council Special Report No.

November

John Campbell

U.S. Policy to Counter

Nigeria’s Boko Haram

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think

tank, and publisher dedicated to being a resource for its members, government ocials, business execu-

tives, journalists, educators and students, civic and religious leaders, and other interested citizens in order

to help them better understand the world and the foreign policy choices facing the United States and other

countries. Founded in , CFR carries out its mission by maintaining a diverse membership, with special

programs to promote interest and develop expertise in the next generation of foreign policy leaders; con-

vening meetings at its headquarters in New York and in Washington, DC, and other cities where senior

government ocials, members of Congress, global leaders, and prominent thinkers come together with

Council members to discuss and debate major international issues; supporting a Studies Program that fos-

ters independent research, enabling CFR scholars to produce articles, reports, and books and hold round-

tables that analyze foreign policy issues and make concrete policy recommendations; publishing Foreign

Aairs, the preeminent journal on international aairs and U.S. foreign policy; sponsoring Independent

Task Forces that produce reports with both findings and policy prescriptions on the most important foreign

policy topics; and providing up-to-date information and analysis about world events and American foreign

policy on its website, CFR.org.

The Council on Foreign Relations takes no institutional positions on policy issues and has no aliation

with the U.S. government. All views expressed in its publications and on its website are the sole responsibil-

ity of the author or authors.

Council Special Reports (CSRs) are concise policy briefs, produced to provide a rapid response to a devel-

oping crisis or contribute to the public’s understanding of current policy dilemmas. CSRs are written by

individual authors—who may be CFR fellows or acknowledged experts from outside the institution—in

consultation with an advisory committee, and are intended to take sixty days from inception to publication.

The committee serves as a sounding board and provides feedback on a draft report. It usually meets twice—

once before a draft is written and once again when there is a draft for review; however, advisory committee

members, unlike Task Force members, are not asked to sign o on the report or to otherwise endorse it.

Once published, CSRs are posted on www.cfr.org.

For further information about CFR or this Special Report, please write to the Council on Foreign Rela-

tions, East th Street, New York, NY , or call the Communications oce at ... Visit

our website, CFR.org.

Copyright © by the Council on Foreign Relations ® Inc.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

This report may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form beyond the reproduction permitted

by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law Act ( U.S.C. Sections and ) and excerpts by

reviewers for the public press, without express written permission from the Council on Foreign Relations.

To submit a letter in response to a Council Special Report for publication on our website, CFR.org, you

may send an email to [email protected]rg. Alternatively, letters may be mailed to us at: Publications Depart-

ment, Council on Foreign Relations, East th Street, New York, NY . Letters should include the

writer’s name, postal address, and daytime phone number. Letters may be edited for length and clarity, and

may be published online. Please do not send attachments. All letters become the property of the Council

on Foreign Relations and will not be returned. We regret that, owing to the volume of correspondence, we

cannot respond to every letter.

This report is printed on paper that is FSC® Chain-of-Custody Certified by a printer who is certified by

BM TRADA North America Inc.

Foreword vii

Acknowledgments ix

Council Special Report

Introduction

The Political Context of Boko Haram

An Anatomy of the Boko Haram Insurgency

The Jonathan Government’s Response to Boko Haram

The United States and Nigeria

Recommendations for U.S. Policy

Conclusion

Endnotes 27

About the Authors 30

Advisory Committee 31

CPA Advisory Committee 32

CPA Mission Statement 33

Contents

vii

Foreword

Boko Haram, an Islamist separatist movement based in northern Nige-

ria, has captured the attention of policymakers in Nigeria and around

the world with its potent blend of religious fanaticism, social media

savvy, and cold-blooded violence. Its most notorious act was the kid-

napping of some two hundred girls from a school in Chibok in April

, but it has killed thousands through assaults on villages, car bomb-

ings, and mass killings of supposed political opponents.

Nigeria’s president, Goodluck Jonathan, calls Boko Haram a new

front in the global war on terror, one that demands a forceful response.

Yet the Nigerian military’s fight against Boko Haram has been under-

mined by accusations of incompetence, collusion, and cruelty nearly on

par with that of the terrorist group it seeks to defeat, and has done little

to curb the group’s spread.

In this Council Special Report, John Campbell, CFR’s Ralph Bunche

senior fellow for Africa policy studies, situates Boko Haram in the con-

text of Nigeria’s larger political situation and draws out consequences

for policymakers in Abuja and Washington. The terrorist group itself

he finds to be opaque, with few clear answers about its leadership, con-

nections to other jihadist groups, funding sources, or even political

goals. Its power and reach have grown mainly through its willingness

to brutalize and intimidate local populations. But it has also resonated

with a suspicion among some northern Muslims that Western educa-

tion and democratic institutions are secular, untrustworthy, and pos-

sibly forbidden by Islam.

Nigeria’s government, meanwhile, has not helped its own case. A

small political elite holds the keys to—and the financial benefits of—

political power. Corruption is common and rarely punished. And the

security services, often the most visible face of government, are reported

to commit violent acts with impunity. As the political establishment

viii Foreword

gears up for presidential elections in , Boko Haram and the govern-

ment response to it are likely to be major points of debate.

The United States, Campbell writes, has an interest in ensuring the

stability and democratic future of Nigeria, as both ends in themselves

and as a means to blunt the advance of Boko Haram. Unfortunately,

Washington’s ability to eect change is limited. Abundant oil income

means Nigeria is not reliant on U.S. aid, which is in any event modest.

In addition, its size and economic strength make it a dominant power in

regional institutions, a status that further tends to reduce U.S. leverage.

Nonetheless, Campbell oers a number of recommendations for

U.S. policy. In the short term, he calls for the consistent inclusion of

human rights issues in all American dealings with Abuja, including call-

ing for accountability for security service crimes; pressure for free and

fair elections in and beyond; facilitating humanitarian assistance in

northern Nigeria; and establishing a consulate in Kano. Over the longer

term, he recommends providing practical and diplomatic support for

government bodies, nongovernmental organizations, and individu-

als working to improve the practice of democracy and human rights in

Nigeria; using U.S. law to penalize corrupt ocials; and encouraging a

wholesale change in the culture of the military and the police through,

for example, inviting Nigerian participation in the U.S. government’s

International Military Education and Training program.

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram oers a sober assess-

ment of the security situation in northern Nigeria. It argues clearly that

the best route to stability is through the establishment of accountable

and eective democratic institutions. And it recommendations steps

U.S. policymakers can take to contribute to that end. It makes the case

that while Boko Haram may be the most headline-grabbing threat, the

long-term stability of Nigeria is a most serious U.S. and international

interest.

Richard N. Haass

President

Council on Foreign Relations

November

viii

ix

I would like to express my gratitude to the many people who made this

report possible. First, my thanks to CFR President Richard N. Haass

and Director of Studies James M. Lindsay for their support of this

project and their feedback throughout the drafting process.

I would like to thank this report’s advisory committee chaired by

Michelle Gavin for lending its expertise and providing indispens-

able input and feedback. Committee members were Pauline H. Baker,

Herman J. Cohen, Jean Herskovits, Ernst J. Hogendoorn, Princeton N.

Lyman, Geo D. Porter, Knox Thames, Alexander Thurston, George

Ward, and Jacob Zenn. They greatly improved the substance of the

report and sharpened its arguments. In addition, I am grateful to Ray-

mond W. Baker for his suggested lines of inquiry.

I am grateful for the assistance of Patricia Dor, Eli Dvorkin, and

Ashley Bregman in CFR’s Publications Department, who provided

unmatched editing support. Courtney Doggart, Tricia Miller Klapheke,

Jake Meth, and Karina Piser in CFR’s Global Communications and

Media Relations department provided invaluable guidance and help in

the marketing eorts for this report. I also appreciate the contributions

of the David Rockefeller Studies Program sta, including Amy Baker.

I would like to thank my colleague and Director of the Center for

Preventative Action (CPA) Paul B. Stares, who provided needed guid-

ance and insights. I would also like to thank the entire CPA team includ-

ing Helia Ighani, Anna Feuer, and Amelia Wolf, who helped guide me

through the development process.

Finally, I would like to thank the Africa policy studies team at CFR

for its help throughout this process. Many thanks to the Africa studies

interns, Charlotte Renfield-Miller, Amanda Roth, and Thomas Zuber,

for their administrative and research support. I am especially grateful

for the help and support of my research associates, Emily Mellgard,

Acknowledgments

x

Allen Grane, and Asch Harwood without whom this report would not

have been completed.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Cor-

poration of New York. The statements made and views expressed

herein are solely my own.

John Campbell

Acknowledgments

Council Special Report

Introduction

The April kidnapping of more than schoolgirls from Chibok in

northern Nigeria by the militant Islamist group Boko Haram—and the

lethargic response of Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan’s govern-

ment—provoked outrage. But the kidnapping is only one of many chal-

lenges Nigeria faces. The splintering of political elites, Boko Haram’s

revolt in the north, persistent ethnic and religious conflict in the coun-

try’s Middle Belt, the deterioration of the Nigerian army, a weak federal

government, unprecedented corruption, and likely divisive national

elections in February with a potential resumption of an insurrec-

tion in the oil patch together test Nigeria in ways unprecedented since

the – civil war.

The United States cannot be indierent. Boko Haram poses no

security threat to the U.S. homeland, but its attack on Nigeria, and the

Abuja response characterized by extensive human rights violations,

does challenge U.S. interests in Africa. Nigeria has been a strategic

partner and at times a surrogate for the United States in Africa. With

million people equally divided between Christians and Muslims,

the benefit of Africa’s largest oil revenues, and in the past a relatively

modern military, Nigeria has had greater heft than any other Afri-

can country. The national aspiration for democracy survived a gen-

eration of military rule and served as an example for other developing

countries. But, if the country has been the “giant of Africa,” Nigeria’s

current challenges politically destabilize West Africa, potentially pro-

viding a base for jihadist groups hostile to Western interests, fueling

a humanitarian crisis, and by example discrediting democratic aspira-

tions elsewhere in Africa.

Upcoming Nigerian elections will shape the country’s trajectory. The

electoral process—the campaign period, polling, and ballot counting—

is likely to be bitter, especially at the local and state levels. Splintered

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

elites are already violently competing for power and appealing to reli-

gious and ethnic identities.

If Nigeria’s civilian government is to forestall an implosion involving

Boko Haram and the elections, and to resume its positive regional

role, it needs to end ubiquitous human rights abuses by ocial entities,

orchestrate humanitarian relief to refugees and persons internally dis-

placed by fighting in the north, and ensure credible elections that do

not exacerbate internal conflict. If it achieves these goals, Nigeria could

resume its evolution into a democratic state that abides by the rule of

law and pursues a regional leadership role commensurate with its size

and supportive of goals shared with the United States.

Unfortunately, the United States and other outsiders have little

leverage over the Jonathan government. Nigeria’s principal exports

and economic drivers—oil and gas—command a ready international

market. The country’s size gives it an advantage over its neighbors, even

in its weak state. Neither the Economic Community of West African

States (ECOWAS) nor the African Union (AU)—the relevant security

organizations—is expected to pressure the Abuja government, because

Nigeria is the largest contributor to their budgets and presides among

African states as the continent’s leader.

1

The country receives minimal

assistance from international donors; U.S. assistance, about $ mil-

lion in , paled in comparison with government revenue.

2

Washington faces hard choices. Enhanced U.S. security cooperation

with Abuja against Boko Haram might limit the movement’s military

activities. Conversely, a visible U.S. military presence risks an anti-

Western backlash in the north and across the Sahel, where the govern-

ment of Jonathan, who is Christian, is suspected of being anti-Muslim.

In the run-up to the February national elections, Washington sup-

ports Nigerians working for credible polling in an environment free of

violence. But even with its strong financial and diplomatic support, U.S.

ability to influence the conduct of Nigeria’s elections is limited by the

country’s enormous size, diversity, and security challenges, not least

from Boko Haram.

Nigeria’s restoration of a democratic, regional leadership trajectory

should be a top Africa policy goal for the Obama administration. As in

the past, a restored partnership with Abuja could forestall the need for

deeper U.S. involvement in the Sahel when Washington is preoccupied

with pressing foreign policy challenges in other regions.

Introduction

The Boko Haram insurgency is a direct result of chronic poor gov-

ernance by Nigeria’s federal and state governments, the political mar-

ginalization of northeastern Nigeria, and the region’s accelerating

impoverishment. The insurgency’s context is a radical, Salafist Islamic

revival that extends beyond the movement’s supporters. Government

security service human rights abuses drive popular acquiescence or sup-

port for Boko Haram. Washington should follow a short-term strategy

that presses Abuja to end its gross human rights abuses, conduct credi-

ble national elections in , and meet the immediate needs of refugees

and persons internally displaced by fighting in the northeast. It should

also pursue a longer-term strategy to encourage Abuja to address the

roots of northern disillusionment, preserve national unity, and restore

Nigeria’s trajectory toward democracy and the rule of law.

The following steps should be taken in the short term:

Washington should pursue a human rights agenda with Abuja, press-

ing the Jonathan administration to investigate credible claims of

human rights abuses and to prosecute the perpetrators;

the Obama administration should pursue a democratic agenda,

including its support for credible elections in ;

the United States should facilitate and support humanitarian assis-

tance in the north; and

the Obama administration should strengthen its diplomatic pres-

ence by establishing a consulate in Kano, the largest city in northern

Nigeria.

The following steps should be taken over the long term:

Washington administrations should identify and support individual

Nigerians working for human rights and democracy;

the United States should revoke the visas held by Nigerians who

commit financial crimes or promote political, ethnic, or religious vio-

lence; and

Washington should encourage Nigerian initiatives to revamp the cul-

ture of its military and police.

Nigeria is divided into more than ethnic groups and its popula-

tion is split evenly between Christians and Muslims.

3

Christians are

predominant in the southern half of the country, Muslims are mostly

in the north, and religious and ethnic minorities can be found every-

where. Nigerian politicians exploit ethnic and religious identities,

especially around elections, and associated violence has accelerated

since the end of military rule in . Violence also tends to occur

where ethnic, religious, and land-use boundaries coincide. Few perpe-

trators of ethnic and religious aggression have ever been held account-

able in a court of law.

Although Nigeria has the largest economy in Africa, up to per-

cent of its population is categorized as “very poor.” In rural areas, the

rate rises to percent.

4

The federal government and its national oil rev-

enue have long since been captured by a tiny number of cooperating and

competing elites.

Politics have had little relevance to the Nigerian people outside elite

circles. Non-elite Nigerians appear to fear the government. The mili-

tary and the police, which, for most people, constitute the face of the

federal government, are routinely brutal.

5

The judicial system often

fails to provide justice, and accountability under the law is frequently

absent for elites. Corruption is pervasive and the common perception

is that it is getting worse.

Since the restoration of civilian government in , political power

in Nigeria has normally been exercised by elites using the ruling Peo-

ple’s Democratic Party (PDP) as their vehicle. Before the elec-

tions, much of the elite, following the principle of power alternation

between north and south and between Muslim and Christian, reached

a consensus on the presidential nominee, as per a arrangement

initially orchestrated by Nigeria’s military rulers. Elites then ensured

that the election was rigged in favor of their consensus candidate. If the

The Political Context of Boko Haram

president was Christian, then the vice president would be Muslim, and

vice versa.

6

Power alternation was not a matter of law. Rather, it was

an elite arrangement that promoted political stability in a country with

numerous ethnic and religious divisions.

7

Elites controlled the Independent National Electoral Commission

(INEC), which is responsible for the conduct of elections. Until ,

each national election since was worse than its predecessor, and

ballot stung, police intimidation, and counting irregularities were

common. Following the elections, the president appointed retired

Chief Justice Muhammadu Uwais to head a special commission (now

called the Uwais Commission) to make recommendations for improve-

ment. The commission did so, but the recommendations were never

completely implemented. President Jonathan also appointed nota-

ble reformer Attahiru Jega chairman of the INEC. But his authority

remains limited because governors still appoint other commissioners.

Boko Haram’s success has been facilitated by the ending of

the arrangement of presidential alternation between north and south.

When President Umaru Yar’Adua, a northern Muslim, died in ,

Vice President Jonathan indicated that he would finish out the presiden-

tial term, but would not run in , because it was still the north’s turn

for the presidency under the eight-year power alternation rhythm.

8

But

in the elections, he ran and won nearly all the states outside the

predominately Muslim north, suspending power alternation. The elec-

tions lacked credibility for many northerners and widespread rioting

followed the announcement of the results.

With the south—much more economically and socially advanced

in Western terms—controlling the federal government, northern

elites faced the prospect of the political wilderness. Paradoxically, if

the elections alienated many of the northern elites from Abuja,

they also widened the gap between many northern Nigerians “on the

street” and their traditional Islamic leaders, some of whom accepted

payos to support Jonathan rather than the northern Muslim candi-

date, Muhammadu Buhari. As these traditional leaders lost author-

ity among the population, Boko Haram was well positioned to fill the

resulting vacuum.

The end of power alternation, a series of political mistakes by the

Jonathan government, pressure from Boko Haram, and the prospect

of a renewed insurrection in the oil patch inform the causes and con-

sequences of elite disunity. Many Nigerians believe that an opposition

The Political Context of Boko Haram

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

candidate could defeat President Jonathan in . This new aspiration

puts a premium on electoral conduct and results that are credible. Many

Nigerian civil organizations, however, are pessimistic about the state of

electoral preparation for .

President Jonathan argues that Boko Haram is a new front in the inter-

national war on terrorism. Accordingly, he says, Nigeria’s war on Boko

Haram requires international involvement.

9

Jonathan has had some

success in selling this perspective. The Obama administration, under

pressure from Congress, designated Boko Haram a foreign terrorist

organization, and has oered a multimillion-dollar reward for informa-

tion regarding the whereabouts of Abubakar Shekau, the best-known

Boko Haram warlord. The UN Security Council added Boko Haram

to the list of “Entities Associated with al-Qaeda” at Nigeria’s request.

10

Mohammed Yusuf, a charismatic malam (teacher) based in the capi-

tal of the northern state of Borno, Maiduguri, organized the Congre-

gation of the People of Tradition for Proselytism and Jihad,

now called

Boko Haram, around .

11

The group saw the government as evil

and considered participating Muslims to be infidels. Although it did

not eschew violence, killing was not its primary characteristic. Boko

Haram probably had political connections within the Borno state gov-

ernment.

12

In what was perhaps a response to police brutality, the group

launched a revolt in July that security forces suppressed, killing

some eight hundred members of the community. The police extrajudi-

cially executed Yusuf and several close relatives. The movement then

went underground.

Mohammed Yusuf had two deputies: Abubakar Shekau and

Mamman Nur; a third, close associate was Khalid al-Barnawi. Though

initially they worked together to reestablish Boko Haram after ,

Nur and al-Barnawi subsequently broke with Shekau because, they

said, he was killing too many Muslims. They organized the Vanguard

for the Protection of Muslims in Black Lands, commonly called Ansaru.

Ansaru’s operations were directed primarily against Christians and the

security services rather than those Muslims who participated in the fed-

eral government. Ansaru probably had links to al-Qaeda in the Islamic

An Anatomy of

the Boko Haram Insurgency

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

Maghreb, al-Shabab, and other radical groups. Ansaru may have intro-

duced suicide bombing and kidnapping to the struggle against the Nige-

rian government.

13

The relationship between Shekau and Ansaru is likely fluid. Ansaru

has been silent for many months, and it is possible that its operatives

have recently rejoined Shekau’s followers, potentially following an

obscure power struggle that resulted in a collective leadership. The kid-

napping of the Chibok schoolgirls has the characteristics of an Ansaru

operation, though Shekau claims Boko Haram is responsible for it.

There are remarkably few hard facts about Boko Haram. It has pub-

lished no political program and the structure of its leadership is largely

unknown. Abubakar Shekau is familiar through his videos, but it seems

likely that he now shares power within the movement.

14

In part because

of its mysteriousness, Boko Haram has become a political football in

the run-up to the elections. The degree of public support for Boko

Haram and the number of its operatives is also unknown.

15

Funding and

weapons are probably largely locally sourced, but if there is some inter-

national support, its origins and scope are unclear.

16

Boko Haram is brutal, fully exploiting the propaganda value of

violence. Its murder methods are grisly, featuring throat-slitting and

beheadings, which it sometimes captures on video for propaganda pur-

poses. Initially, most of its victims were members of the security forces,

persons associated with the government, and Muslims who actively

opposed the group. Now, however, victims include women, children,

and Muslims who merely do not actively support its agenda.

Boko Haram accelerated its attacks over the past year. In the cities of

Gwoza and Damboa in Borno state, Boko Haram murdered or expelled

Christians and all Muslims opposed to it, killing the respected emir

of Gwoza in May . As of September , Boko Haram was able

to operate freely in a territory about the size of Rhode Island and pro-

claimed Gwoza as part of a “caliphate.” It has now carried out bomb-

ings in Abuja and one in Lagos, far from its northeastern heartland.

17

The group regularly slaughters adolescent male students in schools

that it attacks, and kidnaps women and girls for ransom or slavery with

increasing frequency.

Is Boko Haram primarily an indigenous expression of a variety of

Islamic fundamentalism that has evolved into an insurgency against

the Nigerian political economy, or is it a part of the al-Qaeda terrorist

An Anatomy of the Boko Haram Insurgency

network that poses a direct threat to the West as President Jonathan

maintains? With so little hard evidence, the most convincing hypoth-

esis remains that Boko Haram is predominately a diuse, Islamist,

Nigeria-centered insurgency. Its rhetoric attests to its roots in the

widespread cultural opposition to “secularism” and “Westernization”

that the British introduced and that controlling elites have advanced

ever since. Other than rhetorical salvos, it appears uninterested in the

United States.

This perspective minimizes—without denying—the significance of

contacts and links between Boko Haram and al-Qaeda in the Islamic

Maghreb, al-Shabab in Somalia, or the Movement for Unity and Jihad

in West Africa in Mali. But even if its character remains predominantly

indigenous, Boko Haram’s rhetoric is acquiring something of an inter-

national focus, especially as the United Kingdom, France, Israel, and

the United States continue to support the Abuja government. Shekau

now regularly demonizes President Barack Obama in his videos.

Until now, Boko Haram has acted more like a violent, apocalyptic,

millenarian movement than a political entity. The group appears funda-

mentally uninterested in economic development. Boko Haram shares

its anti-Western, antisecular, and antidemocratic stance with other

Nigerian Islamist communities that preach similar positions but do

not resort to violence.

18

Many northern Nigerians who do not adhere

to Boko Haram consider Western education fraudulent because it was

imposed on a Muslim population by Europeans and their Nigerian

successors, thereby undermining traditional Islamic values. From this

perspective, Western education promotes secularism and corruption

and makes materialism and hedonism the ultimate values. This agenda

is perceived as promoting an alternative god to Allah and therefore is

idolatry. Boko Haram draws on this grassroots sentiment.

Boko Haram’s rhetoric emphasizes justice for the poor through

the rigid application of sharia, or Islamic law. From its statements and

videos, Boko Haram claims to reflect the true Islam, and other Muslims,

especially those within the Nigerian establishment who support the

Abuja government, are considered apostates and infidels who deserve

to die. This accusation serves as the group’s justification for the whole-

sale killing of Muslims external to their movement. Thus far, Boko

Haram seems to be immune to the influence of outside, mainstream

Islamic institutions, such as the Organization of Islamic Countries.

Shekau stated the following in a recent video:

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

I am going to kill all the imams and other Islamic clerics in Nige-

ria because they are not Muslims since they follow democracy

and constitution. It is Allah that instructed us, until we soak the

ground of Nigeria with Christian blood, and so-called Muslims

contradicting Islam. We will kill and wonder what to do with their

smelling corpses. This is a war against Christians and democracy

and their constitution.

19

In another video, Shekau contends that “the concept of government

of the people, by the people, for the people cannot continue to exist. It

shall soon, very soon, be replaced by government of Allah, by Allah, for

Allah.” He rejects the Nigerian flag and national anthem as manifesta-

tions of the worship of the secular state.

20

Boko Haram will likely try to

sabotage the elections.

Boko Haram may be moving to create an alternative government

based on the rigid implementation of Islamic law. In a video released

in August, Shekau said that Boko Haram is establishing a caliphate

based in Gwoza, but provided no details. He praised the emergence of

a caliphate in territory controlled by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria

(ISIS), but said nothing about its relation to a Borno caliphate.

President Jonathan declared a state of emergency in the three northern

states of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa in May , which he renewed

in November and May . He concentrated domestic military

assets in the three states and recalled others from international peace-

keeping missions. The military, the state security services, and the

police are consolidated into a Joint Task Force (JTF). Subsequently, in

, these forces were reorganized into the Seventh Division, which

reported directly to the chief of army sta, a close ally of President Jona-

than’s. In some places, irregular vigilantes known as the Civilian JTF

assist the division.

The army dominates the security services, which suer low morale

and poor leadership and are sapped by corruption. Despite a projected

defense budget of nearly $ billion, Boko Haram regularly outguns

security forces.

21

Jonathan has also said that Boko Haram has pene-

trated his government and many Nigerians believe it has also infiltrated

the army.

22

In some cases, unlocked gates or absent patrols have facili-

tated Boko Haram’s operations against military establishments, and

the high number of government armory weapons that Boko Haram

employs hint at collusion. Increasingly, army units melt away at Boko

Haram’s presence.

23

Amnesty International published a report in May

stating that the army had four hours’ notice that Boko Haram was

going to attack Chibok, the town where the kidnapped girls were gath-

ered to take their final examinations. Yet no steps were taken to aug-

ment security.

24

There has long been anecdotal evidence that the Nigerian security

agencies may have killed as many Nigerians as Boko Haram in certain

time periods.

25

Amnesty International released a report on October

, , based on its own investigations, revealing that more than

people died in military custody in the first six months of alone. The

Wall Street Journal also reported on its survey of the morgue records at

The Jonathan Government’s Response

to Boko Haram

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

the University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital. The findings armed

that soldiers routinely brought in large numbers of corpses from Giwa

Barracks, where detainees are held without charge.

26

Following a Boko Haram attack in March on Giwa Barracks,

there have been credible, though unconfirmed, allegations that govern-

ment security personnel killed up to one thousand detainees. The senator

representing Maiduguri said that percent of those detained and subse-

quently killed were “innocent” and not connected to Boko Haram.

27

On September , , PBS screened a documentary as part of its

Frontline series that included video clips from Boko Haram and from

the security services that showed equivalent butchery by both sides.

The Boko Haram videos clearly had propaganda intent; Frontline char-

acterized the security service videos as “trophies” taken by perpetra-

tors with cell phone cameras.

28

President Obama raised the issue of human rights abuses with Pres-

ident Jonathan when the two met in September . U.S. Secretary of

State John Kerry had done the same with President Jonathan in May

. These exchanges appear to have had no eect on the Nigerian

government or on the behavior of the security services.

29

However,

President Jonathan asserts that human rights organizations’ allega-

tions are untrue.

In April , President Jonathan’s national security advisor, Sambo

Dasuki, published a strategy aimed at winning over the population of

the north. Its implementation would command significant Nigerian

government resources. The Jonathan government has yet to provide

the necessary support to this promising initiative. However, even were

it to do so, the Dasuki strategy addresses fundamental, long-term chal-

lenges such as inadequate education; it is not a short-term fix for Boko

Haram depredations in the election period.

30

It is dicult to see how Boko Haram will be defeated. In the past,

other millenarian religious movements in northern Nigeria have

burned themselves out only to reappear in dierent forms because the

rebellions’ social and economic drivers have never been addressed. The

group’s killing of Muslims may turn the population against it or revital-

ized security forces could drive it deep into the bush. Nevertheless, it is

hard to imagine that Boko Haram will vanish by the elections; the

group will likely do all in its power to sabotage the voting.

The George W. Bush administration paid minimal attention to Nige-

rian domestic political developments beyond expressing support for

“free and fair” elections. Washington failed to recognize the Nigerian

government’s growing administrative dysfunction and U.S. ocials

did little to address a cresting wave of corruption, staying mostly silent

when President Olusegun Obasanjo unsuccessfully sought an uncon-

stitutional third term.

31

Washington remained quiet about the blatant

rigging of the elections that placed Obasanjo’s hand-picked suc-

cessor, the ailing Umaru Yar’Adua, in the presidency and the inexperi-

enced Goodluck Jonathan in the vice presidency.

During President Umaru Yar’Adua’s terminal illness in , many

observers feared that a military coup would fill the vacuum in gov-

ernment authority. Washington, relieved that Goodluck Jonathan’s

interim presidency and subsequent election seemed to forestall a coup,

accorded the new president the benefit of the doubt.

The Obama administration’s policy toward Nigeria has been unde-

manding, with ocials only mildly denouncing publicly the human

rights abuses perpetrated by Nigerian security services in their struggle

with Boko Haram. Washington has not exacted a high political price

from Jonathan as these transgressions persist.

32

Pressed by U.S. public

opinion, the administration oered Jonathan assistance in the search

for the kidnapped Chibok schoolgirls, but has not investigated the gov-

ernment’s detention of alleged Boko Haram wives and children without

charge or the large numbers of young men extrajudicially incarcerated

on the basis of mere suspicion.

However, President Obama did not visit Nigeria on either of his

two African trips, a sign of a new concern in his administration about

rigged elections, human rights abuses, and corruption. Nevertheless,

in its rhetoric and its actions, the Obama administration remains sup-

portive of the Abuja government. Accordingly, Jonathan continues to

The United States and Nigeria

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

identify himself with President Obama to appeal to his pro-American,

Christian base; his presidential campaign materials have featured pho-

tographs of him and Obama together.

33

As of March , there is a legal precedent for the U.S. Department

of the Treasury, working with the U.S. Department of Justice, to identify

illicit financial flows through the U.S. financial system to another coun-

try.

34

Those funds could then be frozen. That was done with respect to

$ million looted by the notoriously corrupt dictator Sani Abacha,

Nigeria’s de facto chief of state from to , which he then depos-

ited in banks in France and the Channel Islands.

35

This action may signal

a greater willingness by the U.S. government to deprive foreign political

figures of the fruits of their corruption.

Frustration over the failure to liberate the Chibok schoolgirls, the

Nigerian military’s manifest inadequacies for the task, and the Jona-

than government’s visibly weak political will has prompted some in

Congress and the media to call for U.S. military intervention to liber-

ate the girls.

Any such course is fraught with peril. In earlier kidnapping episodes,

eorts to free the victims by the use of force have led to their captors

murdering them—a possible fate for the schoolgirls in the event of a

military operation.

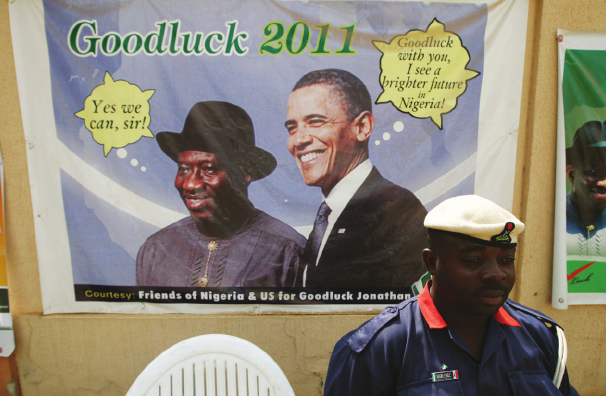

A campaign poster for Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan emphasizes his relationship with

U.S. President Barack Obama, in Abuja, Nigeria, January , . (Sunday Alamba/AP Photo)

The United States and Nigeria

Overt U.S. military intervention also risks further alienating the

Muslim population in Nigeria and across the Sahel. Already, north-

ern Nigerian field preachers have issued warnings in sermons against

European and American military boots on Nigerian ground.

36

Retired

general and former President Olusegun Obasanjo, probably echoing

widespread views among Nigerian ocers, has publicly criticized Pres-

ident Jonathan’s request for outside assistance against Boko Haram,

particularly from Europe or the United States.

37

So far, the U.S. military has trained only small numbers of Nigerians

to participate in international peacekeeping forces. The U.S. Depart-

ment of State’s budget request for International Military Education

and Training (IMET) for Nigeria in fiscal year is only $,.

38

(IMET is a vehicle for the provision of such U.S. training to a foreign

country.) Nigerian reluctance to accept further U.S. training with its

requirements for fiscal accountability and transparency has inhibited

the program’s expansion in the past. In addition, the Leahy amendment

prohibits U.S. military training of foreign units that violate human

rights with impunity.

39

U.S. embassies and relevant bureaus in the

Department of State vet units for eligibility. If they are found ineligible,

American training is suspended until the host government brings to

justice those responsible for human rights violations.

The number of Nigerian units that can pass Leahy vetting is small

and shrinking. Military units are rotated through the north, making

them vulnerable to credible charges of human rights violations. There is

no public indication that a significant number of military perpetrators

of human rights violations have been brought to justice.

In May , the U.S. Department of Defense deployed twelve

active-duty U.S. soldiers to Nigeria to train a -man Nigerian ranger

battalion for combat operations that would presumably be free of the

taint of human rights violations. This was the first time in years that the

United States trained Nigerian military units for operations other than

peacekeeping missions. However, isolated trainings are unlikely to have

a lasting eect on Nigerian military culture. Abuja’s stance toward secu-

rity cooperation with the United States continues to be unenthusiastic,

despite President Jonathan’s request for assistance in the aftermath of

the Chibok kidnappings. Trainings, even if small, link the American

and Nigerian militaries and thereby risk tarring the United States with

the Nigerian security sector’s ongoing human rights violations.

Nevertheless, improving the professionalism of the Nigerian mili-

tary and other security services is in the interests of the Nigerian people,

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

Nigeria’s neighbors, and the United States. Were Abuja to investigate

allegations of human rights abuses by the security forces, and were the

security services receptive, the door would open to greater U.S. assis-

tance that over time could improve their professionalism and thereby

their performance.

At the request of the Nigerian government, the United States is

deploying drones and surveillance aircraft concentrated on finding the

Chibok schoolgirls. That program may be expanded. The territory to

be searched is roughly the size of New England. How valuable the intel-

ligence acquired by such surveillance will be in finding and liberating

the Chibok girls remains to be seen.

The expanded surveillance option would require the United States to

deploy additional assets, which would likely require more support per-

sonnel, especially in a region that lacks basic infrastructure. Increased

deployment will make the U.S. presence more obvious to a Muslim

population that is already suspicious of the West.

The U.S. political response to Boko Haram continues to be hobbled

by a lack of understanding about the latter’s methods and goals. Given

Boko Haram’s threat to the Nigerian state and its potential for stronger

links to international terrorism, the United States needs to deepen its

understanding of the organization’s leadership, structure, funding, and

sources of support. U.S. eorts should be coordinated with other gov-

ernments that have significant on-the-ground knowledge of the Sahel,

perhaps by means of a contact group.

Given Nigeria’s current travails, the watchword for Washington

policy initiatives should be “first, do no harm.” An increasingly brutal

civil war between Islamist radicals and government security forces

capable of the most egregious human rights abuses poses potential

pitfalls. American missteps such as an overly militarized response in

northern Nigeria could compromise U.S. interests throughout Muslim

West Africa. Protecting those interests in Nigeria and in the Sahel will

require trade-os. For example, a stronger Washington stance on Nige-

rian human rights abuses could make Abuja less cooperative in such

venues as the UN Security Council, at least in the short term. But, it is

the policy with the best prospect for mitigating Boko Haram’s radical-

ization of West Africa’s largest Muslim population.

In the coming six months, Nigeria’s civilian government faces a pos-

sible implosion involving Boko Haram and the elections. It is in

the interests of the United States that Nigeria preserve its national unity

and resume its democratic trajectory so that Abuja once again can part-

ner with Washington on Africa’s strategic challenges. Yet Washington

has little leverage over the Jonathan government and the country’s frac-

tured political class. If Washington cannot be indierent to Nigeria’s

future, it can shape the outcome only at the margins.

Boko Haram is a security threat to Nigeria, and, as such, it retards

U.S. goals in Africa. But, Boko Haram at present poses no threat to the

security of the homeland of the United States. Boko Haram has under-

taken no operations against U.S. public or privately owned facilities, in

Nigeria or elsewhere. It has kidnapped no Americans. Unlike al-Sha-

bab, it enjoys no support from expatriates living in the United States.

Unlike the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, it has recruited as fighters no

U.S. citizens or nationals of other Western countries who could estab-

lish terrorist cells on returning home. The central al-Qaeda leadership

does not control Boko Haram and has openly criticized its brutality.

Boko Haram’s attention has been on Nigeria, not the furtherance of

an international jihad beyond the Sahel, despite President Jonathan’s

claims to the contrary.

With a defense budget approaching $ billion, the Jonathan admin-

istration is not short of resources. Rather than securing an enhanced

military capability, Abuja’s challenges are to address poor governance,

rebuild a national political consensus, and reduce the northern Muslim

sense of marginalization. Its immediate goal should be to neutral-

ize Boko Haram in the run-up to the national elections, even if it

cannot be defeated. Absent a political initiative, a robust U.S. security

package would be unlikely to tilt the scales against Boko Haram even

if Abuja were to accept it. Hence, Washington should urge and assist

Recommendations for U.S. Policy

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

Abuja to undertake policy changes that will isolate Boko Haram and

reduce its regional appeal. Given Abuja’s human rights abuses, there is

little that Washington can do at present in the security realm against

Boko Haram in partnership with the Nigerian army and security ser-

vices. Were Abuja to take steps against those abuses, however, it would

likely help mitigate northern alienation and as well open the door to an

expansion of the U.S. IMET program.

Washington needs to recognize unpalatable realities as it devises its

Nigeria policy for both the short term in the run-up to elections and

for the long term afterward. As for political initiatives, it is too late

for Washington to urge Abuja to complete implementation of serious

reforms of the electoral process before , as recommended by the

Uwais Commission. Likewise, U.S. policy toward Nigeria after the

elections will depend on unpredictable factors such as the credibility

of polling and counting, the level of violence, the cohesion of the state,

and whether there is military intervention. Whatever unfolds in Feb-

ruary , addressing the drivers of the Boko Haram insurgency and

supporting a democratic trajectory in Nigeria will present long-term

challenges for Abuja and its potential partners.

SHORT-TERM RECOMMENDATIONS

The Obama administration should hold the Abuja government

accountable for security service human rights abuses. It should call on

the Nigerian government to investigate credible claims by human rights

organizations and the media of security service human rights viola-

tions, publish the results, and prosecute the alleged perpetrators.

The White House and State Department should also deplore cred-

ible reports of human rights violations by the security services, just

as they do Boko Haram killings. In addition, senior U.S. elected and

administration ocials should include human rights violations on their

agendas for all meetings with Nigerian counterparts.

Washington should oer to expand IMET and any other appropri-

ate U.S. programs for the professionalization of the security services

should Abuja take concrete steps to address human rights abuses.

The regular meetings of the U.S.-Nigeria Binational Commission—a

Recommendations for U.S. Policy

vehicle for diplomatic consultation between Washington and Abuja—

oer a venue for this dialogue.

The Abuja government might respond by declining to cooperate on

those remaining issues of mutual concern, especially within the UN

Security Council. But, a weak U.S. human rights agenda in Nigeria rein-

forces the Muslim view that Washington is prepared to look the other

way when a Christian government is committing human rights abuses.

In the short term, the pursuit of a diplomatic human rights agenda

with Nigeria should not result in any additional financial costs to the

U.S. government. However, if an expanded IMET or other security

service training initiatives were to become possible, there would be

additional costs, the amount of which would depend on the size of

the program.

The Obama administration should publicly reiterate its support for

free, fair, and credible elections, and maintain modest funding for

electoral support, encouraging eorts by the International Republic

Institute, the National Democratic Institute, and other nongovern-

mental organizations to monitor the election campaigns, polling,

vote counting, and election’s aftermath. The Obama administration

should also avoid early comment on the quality of the elections. The

U.S. Embassy in Abuja and the consulate general in Lagos should

monitor political appeals to ethnic and religious identities in electoral

campaigns as possible harbingers for electoral violence. Moreover,

the State Department should revoke the American visas of those who

advocate or perpetrate violence.

Visa revocation is a cumbersome process, and there could be

bureaucratic push back from U.S. government agencies that are under-

resourced. However, many in the Nigerian elite place high value on

travel to the United States. Potential loss of a visa to do so could influ-

ence their behavior.

The Obama administration should encourage and assist the Jonathan

government to develop and lead a multilateral program of humanitarian

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

assistance for the displaced populations in the north and the Nigerian

refugees who have crossed into Niger, Chad, and Cameroon.

The Nigerian National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA)

has a formal structure in place to address internally displaced persons.

The Obama administration should direct the U.S. Agency for Inter-

national Development (USAID) and other relevant U.S. agencies to

explore what technical assistance the United States could provide those

agencies to meet immediate emergencies.

Private organizations, ranging from the Red Cross/Red Crescent to

Christian and Islamic relief agencies, are present in the north, though

often with only a weak capacity. USAID should encourage and facili-

tate coordination of their eorts by providing occasions and venues

for their leaderships to meet. Refugees are the responsibility of the UN

High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) based at the European

oces of the United Nations in Geneva. The U.S. Mission in Geneva

should open a dialogue with UNHCR on Sahelian refugee flows and

look for opportunities diplomatically to support its work, especially in

Niger and Cameroon.

Humanitarian assistance would require careful planning, given the

security challenges. As with any emergency relief program, there would

be costs, but in the past, the American public has supported food and

medicine deliveries. Humanitarian assistance to an Islamic population

could have a positive impact on the region’s view of the United States

and balance the widespread view that Washington uncritically accepts

Abuja’s record of poor governance.

..

The United States needs a diplomatic presence in the north in order to

understand and shape developments in that volatile region, particularly

as the elections approach. A consulate also becomes an important

instrument of American outreach to Nigeria’s Muslim population.

The opening of a consulate in Kano was approved by former U.S.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton during President Obama’s first

administration, but was shelved because the security risks and costs

were judged to be too high. Given the partisan rancor in Washing-

ton following the terrorist attack on the U.S. facility in Benghazi,

moving forward with a Kano consulate requires political courage.

Recommendations for U.S. Policy

The absolute security of a diplomatic establishment can never be

guaranteed. Nevertheless, the United States has successfully met ter-

rorist security challenges in Kandahar and Karachi, and could do so in

Kano. The financial costs will be high. But, the public diplomacy and

political benefits of a U.S. diplomatic presence in this volatile region

make the investment worthwhile.

Implementation of these recommendations is necessary for the

credibility of U.S. advocacy for human rights and democracy, not just

among Muslims in Nigeria but also in West Africa. Implementation will

also encourage and support Nigerians working for credible elections

and may discourage overt appeals to ethnic and religious hatred. But

the United States can assist only at the margins in containing the violent

pressures associated with the Boko Haram insurgency, the Nigerian

government’s response to it, and national elections.

LONG-TERM RECOMMENDATIONS

If Nigeria successfully meets the challenges of the next six months, then

the government buys time to address the deeper causes of northern

alienation and impoverishment that drives Boko Haram. Although the

impetus for fundamental reform and transformation will need to come

from Nigeria’s political elites, the United States can usefully contribute

to this longer-term eort.

The Obama administration should encourage the Jonathan govern-

ment to launch a counterinsurgency strategy against Boko Haram

by oering technical support. That could include an expanded IMET

program to increase the professionalism of the security services if

Abuja meets the requirements of the Leahy amendment. The Obama

administration should also urge the Jonathan government to publicize

and implement the Uwais Commission’s recommendations for the

improvement of elections.

The U.S. Embassy in Abuja, the consulate general in Lagos, and a

consulate in Kano, when it is established, should increase their con-

tacts with Christian and Muslim religious leaders and traditional rulers

U.S. Policy to Counter Nigeria’s Boko Haram

working toward peace and reconciliation. They should also seek to

establish links with “field preachers” and increasingly influential indi-

viduals outside the traditional establishments.

American ocials should identify eective governors who provide

a model of good governance and publicize their eorts. USAID should

continue its strategy of working exclusively with state governments

with a good track record.

The Obama administration should encourage new trade and invest-

ment in the north. It should also draw attention to new, private Nigerian

investment in the region, perhaps in conjunction with organizations

such as the Corporate Council for Africa and the Business Council for

International Understanding.

Additionally, the United States should expand its Fulbright scholar

program and other exchange programs with Nigeria to highlight its

commitment to democracy and to building Nigeria’s civil society lead-

ership capacity.

To facilitate travel between Nigeria and the United States, the U.S.

Department of State should devote sucient resources to visa process-

ing to eliminate periodic backlogs. Understang of visa ocers at the

embassy, the consulate general, and of those who perform additional

reviews in the State Department in coordination with other federal

agencies can cause a waiting time of months. The National Security

Council should coordinate an executive branch review of procedures

that subject Nigerians and others with Islamic names to secondary

security checks, which delay their travel to the United States. The costs

of this recommendation would be modest.

To ensure that the perpetrators and profits of corruption find no safe

haven in the United States, the U.S. Embassy in Abuja, the consul-

ate general in Lagos, and the State Department’s Bureaus of African

Aairs and Consular Aairs should expand the revocation of visas of

those found to be corrupt as well as of those who perpetuate and advo-

cate political, ethnic, and religious violence. With respect to money

laundering and other financial crimes, the National Security Council

should publicly announce that it is directing the Treasury and Justice

Departments to identify and freeze the profits of corruption that have

passed through the U.S. financial system. Because these processes will

Recommendations for U.S. Policy

be time-consuming, the Obama administration may announce publicly

its intention well in advance of implementation.

A stable, democratic Nigeria requires changes in military and police

culture. In the United States, it has been a long-standing goal to

encourage military and police accountability to civil authority. In addi-

tion to the current small-scale U.S. programs with that goal, or even

an expanded IMET, relevant U.S. agencies should provide extensive

technical assistance to Nigerian institutions working toward security

service accountability. The National Institute for Policy and Strategic

Studies in Kuru and the Center for Peace Studies at Usman Danfodio

University in Sokoto, no doubt among others, have notable programs

that merit U.S. support.

Boko Haram is primarily an indigenous northern Nigerian response

to poverty and bad governance within the context of a breakdown of

regional power alternation and a radical Islamist worldview. Hence, it

would be a mistake for Washington to place Boko Haram in the context

of the international war on terrorism. There is little scope for a military

response by the United States.

Rather than a greater U.S. security role in Nigeria, Washington

should redouble its diplomatic eorts to persuade and encourage the

Abuja government to address the drivers of Boko Haram.

Implementing the recommendations outlined above would likely

result in a cooler bilateral relationship between Washington and Abuja,

at least in the short term. However, they could strengthen American

ties to the Nigerian people, especially civic organizations working for

democracy and good governance.

The United States can assist those in Nigeria working for a demo-

cratic trajectory only at the margins. But it is worth the eort. A demo-

cratic Nigeria characterized by the rule of law would promote economic

development, alleviate poverty, and address the people’s alienation

from their government. Boko Haram would be deprived of its oxygen.

The diplomatic and security partnership between Washington and

Abuja could then be reestablished, relieving the United States of the

need for a greater security presence in West Africa.

Conclusion

1. South Africa would claim that it, too, has the capacity for continental leadership.

2. Susan B. Epstein, Alex Tiersky, and Marian L. Lawson, “State Foreign Operations,

and Related Programs: FY Budget and Appropriations,” Congressional Research

Service, May , , http://fpc.state.gov/documents/organization/.pdf.

3. Estimates of the number of ethnic groups range up to three hundred and fifty. The lack

of precision reflects dierent definitions of “ethnic group” and how to separate them

from other categories, such as “clans.”

4. “Nigeria Economic Report,” World Bank, May , p. .

5. “Nigeria: War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity as Violence Escalates in North-

east,” Amnesty International, March , .

6. Umaru Yar’Adua, elected president in , was a Muslim. His vice president, Good-

luck Jonathan, is a Christian. Although power alternation has been suspended follow-

ing the elections of , President Jonathan has a Muslim vice president.

7. Power alternation, which Nigerians call zoning, is described in detail and analyzed

in John Campbell, Nigeria: Dancing on the Brink, nd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman &

Littlefield, ), chap. and .

8. President Olusegun Obasanjo, a Christian from southwest Nigeria, held oce from

to . Under the principle of alternation, a northern Muslim would hold the

presidency from to .

9. See Maïa de la Baume and Alissa J. Rubin, “West African Nations Set Aside Their Old

Suspicions to Combat Boko Haram,” New York Times, May , , and “President Jona-

than’s Speech in France at the Regional Summit on Security in Nigeria,” Vanguard, May

, .

10. At present, neither designation has much practical eect, though they may inhibit the

ability of third parties to negotiate with Boko Haram in the future.

11. Congregation of the People of Tradition for Proselytism and Jihad, or, in Arabic,

Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati Wal-Jihad.

12. “Curbing Violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram Insurgency,” International Crisis

Group, Africa Report no. , April , .

13. For an extensive discussion of the murky relations among the leaders of Boko Haram

and Ansaru, see Jacob Zenn, “Leadership Analysis of Boko Haram and Ansaru in

Nigeria,” CTC Sentinel, February , .

14. Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram Leader Abubakar Shekau: Dead, Deposed or Duplicated?”

Militant Leadership Monitor , no. , May , pp. –.

15. See Freedom C. Onuoha, “Why Do Youths Join Boko Haram,” United States Institute

for Peace Special Report , June . Onuoha, drawing on research by the CLEEN

Foundation (Lagos) that includes a mapping study and hundreds of interviews, ana-

lyzes why young men are radicalized, but he does not suggest how many there are.

The CLEEN Foundation was formerly known as the Center of Law Enforcement

Endnotes

Endnotes

Education in Nigeria.

16. Boko Haram robs banks and now benefits from ransoms, and many Boko Haram

weapons come from Nigerian army armories.

17. For a map indicating the intensity of Boko Haram, government, and sectarian violence

by state, see the Nigeria Security Tracker, http://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-security-

tracker/p. It is updated monthly.

18. Many of these communities are local in focus and oriented around a charismatic

leader.

19. Horace G. Campbell, “The Menace of Boko Haram and Fundamentalism in Nigeria,”

Pambazuka News, June , .

20. Michael Olugbode and Senator Iroegbu, “Shekau Appears in a Video, Says He’s

Alive,” This Day Live, September , . See also President Jonathan’s “Declaration

of Emergency Rule,” Vanguard, May , . Boko Haram has its own black flag, which

by June was flying in villages that it occupied.

21. Bassey Udo, “Jonathan signs Nigeria’s Budget as Defence gets percent,” Pre-

mium Times, May , .

22. See “Aiding Boko Haram: Army Court-martials Generals, Others,” Leadership,

June , ; “Where Is Safe in Nigeria?” African Seer, January , .

23. See Robyn Dixon, “In Nigeria, Distrust Hampers the Fight Against Boko Haram,”

Los Angeles Times, June , ; Chantal Uwimana and Leah Wawro, “Corruption in

Nigeria’s Military and Security Forces: A Weapon in Boko Haram’s Hands,” Sahara

Reporters, June , .

24. “Nigerian Authorities Failed to Act on Warnings About Boko Haram Raid on School,”

Amnesty International, May , .

25. For graphs of deaths caused by the conflict between the government and Boko Haram

and of related sectarian violence, see the Nigeria Security Tracker, http://www.cfr.org/

nigeria/nigeria-security-tracker/p.

26. For Nigerian security service abuses, see “Spiraling Violence: Boko Haram Attacks

and Security Force Abuses in Nigeria,” Human Rights Watch, October , pp. –;

“Nigeria: More than , Killed in Armed Conflict in North-Eastern Nigeria in Early

,” Amnesty International, March , , pp. –; Adam Nossiter, “Bodies Pour in

as Nigeria Hunts for Islamists,” New York Times, May , ; Drew Hinshaw, “Hundreds

Killed in Jails Swelling with Islamist Suspects,” Wall Street Journal, October , .

27. Ibid.

28. PBS, “Hunting Boko Haram,” Frontline, September , , http://www.pbs.org/

wgbh/pages/frontline/hunting-boko-haram.

29. See “Readout of President Obama’s Meeting with Nigerian President Goodluck Jona-

than,” The White House, September , ; “State of Emergency and Fighting in

Northern Nigeria,” U.S. Department of State, May , .

30. Elizabeth Donnelly, “Boko Haram Will Continue to Rampage While Nigeria Tackles

Accountability,” Guardian, April , .

31. Campbell, Nigeria, p. .

32. The most significant political price was that President Obama declined to visit Nigeria

on either of his two African trips.

33. Caroline Dueld, “Nigeria’s ‘Cash and Carry’ Politics,” BBC, January , .

34. These funds could include those looted by heads of state or other senior ocials from

national treasuries or state-owned enterprises.

35. “U.S. Freezes $m Hidden by Former Nigerian Leader Sani Abacha,” Telegraph,

March , .

36. This point has been made to me repeatedly by northern Nigerian interlocutors.

Endnotes

37. Duro Onabule, “Chibok Girls So Near, Yet So Far,” Sun, May , .

38. U.S. Department of State, International Military Education Training Account Sum-

mary, http://www.stategov/t/pm/ppa/sat/c.htm.

39. The Leahy amendment has been a permanent part of the Foreign Assistance Act since

.

John Campbell is the Ralph Bunche senior fellow for Africa policy

studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. The second edition of

his book Nigeria: Dancing on the Brink was published in June .

He writes the blog Africa in Transition and edits the Nigeria Security

Tracker on CFR.org. From to , Campbell served as a U.S.

Department of State Foreign Service ocer. He served twice in Nige-

ria, as political counselor from to , and as ambassador from

to . Campbell’s additional overseas postings include Lyon,

Paris, Geneva, and Pretoria. He also served as deputy assistant sec-

retary for human resources, dean of the Foreign Service Institute’s

School of Language Studies, and director of the Oce of UN Politi-

cal Aairs. Campbell received a BA and MA from the University of

Virginia and a PhD in seventeenth-century English history from the

University of Wisconsin, Madison.

About the Author

Pauline H. Baker

Fund for Peace

Herman J. Cohen

American Academy of Diplomacy

Michelle D. Gavin

Jean Herskovits

State University of New York, Purchase

Ernst J. Hogendoorn

International Crisis Group

Princeton N. Lyman

Princeton Lyman and Associates

Geo D. Porter

West Point Combating Terrorism Center

Paul B. Stares, ex ocio

Council on Foreign Relations

Knox Thames

U.S. Commission on

International Religious Freedom

Alexander Thurston, ex ocio

Council on Foreign Relations

George Ward

Institute for Defense Analyses

Jacob Zenn

Jamestown Foundation

Advisory Committee for

Nigeria, Boko Haram, and the United States

This report reflects the judgments and recommendations of the authors. It does not necessarily represent

the views of members of the Advisory Committee, whose involvement in no way should be interpreted

as an endorsement of the report by either themselves or the organizations with which they are aliated.

Peter Ackerman

Rockport Capital Inc.

Richard K. Betts

Council on Foreign Relations

Patrick M. Byrne

Overstock.com

Leslie H. Gelb

Council on Foreign Relations

Jack A. Goldstone

George Mason University

Sherri W. Goodman

CNA

George A. Joulwan, USA (Ret.)

One Team Inc.

Robert S. Litwak

Woodrow Wilson International Center

for Scholars

Thomas G. Mahnken

Paul H. Nitze School

of Advanced International Studies

Doyle McManus

Los Angeles Times

Susan E. Patricof

Mailman School of Public Health

David Shuman

Northwoods Capital

Nancy E. Soderberg

University of North Florida

John W. Vessey, USA (Ret.)

Steven D. Winch

Ripplewood Holdings LLC

James D. Zirin

Sidley Austin LLC

Center for Preventive Action

Advisory Committee

Mission Statement

of the Center for Preventive Action

The Center for Preventive Action (CPA) seeks to help prevent, defuse,

or resolve deadly conflicts around the world and to expand the body

of knowledge on conflict prevention. It does so by creating a forum in

which representatives of governments, international organizations,

nongovernmental organizations, corporations, and civil society can

gather to develop operational and timely strategies for promoting peace

in specific conflict situations. The Center focuses on conflicts in coun-

tries or regions that aect U.S. interests, but may be otherwise over-

looked; where prevention appears possible; and when the resources of

the Council on Foreign Relations can make a dierence. The Center

does this by

Issuing Council Special Reports to evaluate and respond rapidly to

developing conflict situations and formulate timely, concrete policy

recommendations that the U.S. government and international and

local actors can use to limit the potential for deadly violence.

Engaging the U.S. government and news media in conflict preven-

tion eorts. CPA sta members meet with administration ocials

and members of Congress to brief on CPA findings and recommen-

dations; facilitate contacts between U.S. ocials and important local

and external actors; and raise awareness among journalists of poten-

tial flashpoints around the globe.

Building networks with international organizations and institutions

to complement and leverage the Council’s established influence in the

U.S. policy arena and increase the impact of CPA recommendations.

Providing a source of expertise on conflict prevention to include

research, case studies, and lessons learned from past conflicts that

policymakers and private citizens can use to prevent or mitigate

future deadly conflicts.

Limiting Armed Drone Proliferation

Micah Zenko and Sarah Kreps; CSR No. , June

A Center for Preventive Action Report

Reorienting U.S. Pakistan Strategy: From Af-Pak to Asia

Daniel S. Markey; CSR No. , January

Afghanistan After the Drawdown

Seth G. Jones and Keith Crane; CSR No. , November

A Center for Preventive Action Report

The Future of U.S. Special Operations Forces

Linda Robinson; CSR No. , April

Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies

Micah Zenko; CSR No. , January

A Center for Preventive Action Report

Countering Criminal Violence in Central America

Michael Shifter; CSR No. , April

A Center for Preventive Action Report

Saudi Arabia in the New Middle East

F. Gregory Gause III; CSR No. , December

A Center for Preventive Action Report

Partners in Preventive Action: The United States and International Institutions

Paul B. Stares and Micah Zenko; CSR No. , September

A Center for Preventive Action Report

Justice Beyond The Hague: Supporting the Prosecution of International Crimes in National Courts

David A. Kaye; CSR No. , June

The Drug War in Mexico: Confronting a Shared Threat

David A. Shirk; CSR No. , March

A Center for Preventive Action Report

UN Security Council Enlargement and U.S. Interests

Kara C. McDonald and Stewart M. Patrick; CSR No. , December

An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

Council Special Reports

Published by the Council on Foreign Relations

Council Special Reports

Congress and National Security

Kay King; CSR No. , November

Toward Deeper Reductions in U.S. and Russian Nuclear Weapons

Micah Zenko; CSR No. , November

A Center for Preventive Action Report

Internet Governance in an Age of Cyber Insecurity

Robert K. Knake; CSR No. , September

An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

From Rome to Kampala: The U.S. Approach to the 2010 International Criminal Court

Review Conference

Vijay Padmanabhan; CSR No. , April

Strengthening the Nuclear Nonproliferation Regime

Paul Lettow; CSR No. , April

An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

The Russian Economic Crisis

Jerey Manko; CSR No. , April

Somalia: A New Approach

Bronwyn E. Bruton; CSR No. , March

A Center for Preventive Action Report

The Future of NATO

James M. Goldgeier; CSR No. , February

An International Institutions and Global Governance Program Report

The United States in the New Asia