Service Evaluation of the Elton John AIDS

Foundation’s Zero HIV Social Impact Bond

intervention in South London:

An investigation into the implementation and sustainability

of activities and system changes designed to bring us closer

to an AIDS free future.

Alec Fraser, Clare Coultas & Alexis Karamanos

Final report March 2022

2

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ................................................................. 3

About the authors ................................................................... 4

Foreword .......................................................................... 5

Executive Summary ................................................................. 7

Introduction........................................................................ 9

Methodological and theoretical approach .............................................. 11

Qualitative approach ............................................................ 12

Quantitative approach........................................................... 12

Ethics ........................................................................ 13

Theoretical approach............................................................ 14

Zero HIV SIB programme background ................................................. 15

Findings .......................................................................... 16

Evaluating the impact of the Zero HIV programme .................................... 16

Evaluating the processes through which the Zero HIV programme functioned ............. 25

Narrative overview .............................................................. 25

Defining the Zero HIV SIB-financed ‘intervention’ .................................... 27

Secondary Care.................................................................... 30

Opt-out HIV testing in the ED ..................................................... 30

LTFU work in the hospital setting .................................................. 35

Primary Care ...................................................................... 38

Awareness Raising.............................................................. 38

Opt-in HIV testing in Primary Care ................................................. 39

LTFU and HIV Support in Primary Care ............................................. 40

Community Care ................................................................... 42

Sustainability...................................................................... 44

Conclusions ....................................................................... 47

References ....................................................................... 50

3

Acknowledgements

This service evaluation is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied

Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King’s College Hospital NHS

Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or

the Department of Health and Social Care.

The authors received funding to support this work from the King’s Business School Research Incubator

Fund in October 2020 and an Impact Fund award in February 2022. We are very grateful to the

KBS Research support team for all their help with this service evaluation and their patience as we

experienced delays linked to COVID-19.

We would like to thank all the research participants who kindly agreed to give up their time to be

interviewed throughout this service evaluation and also answered questions informally at times over the

past year or so.

Thank you to Professor Peter Littlejohns of King’s College London for help and guidance in the

establishment of this service evaluation. Thanks to Clare FitzGerald of King’s College London and

Richard Boulton of Kingston & St George’s University of London for help and advice as the project

developed.

Many thanks also to Steve Hindle, Social Impact Bond Performance Manager, Elton John AIDS

Foundation and Neil Stanworth, Director, ATQ for support throughout the project and for commenting on

earlier drafts of this report.

The interpretation of all the data remains that of the authors.

Please cite this report as Fraser, A., Coultas, C., & Karamanos, A. (2022) Service Evaluation

of the Elton John AIDS Foundation’s Zero HIV Social Impact Bond intervention in South London:

An investigation into the implementation and sustainability of activities and system changes

designed to bring us closer to an AIDS free future. Final Report, King’s College London.

4

About the authors

Dr Alec Fraser is a Lecturer in Government & Business at King’s College London (KCL). He is a member

of the Public Services Management and Organisation Group within the King’s Business School. Alec’s

research centres on the use of evidence in policy making and practice across the public sector with a

particular focus on health and social care. He has extensively researched the development of Social

Impact Bonds and Outcomes-Oriented Reforms in public service delivery in the UK and internationally

over recent years. He previously spent five years at the Policy Innovation Research Unit at the London

School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Prior to entering academia, he worked in NHS administration

and management. He has an MA in Public Policy and a PhD in Management - both from KCL.

Dr Clare Coultas is Lecturer in Social Justice in the KCL School of Education, Communication and

Society, and a is postdoctoral researcher in the South London Applied Research Collaboration (ARC),

based at the KCL Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience. Grounded in her experiences

of working as a third-sector research, evaluation, and development practitioner in the UK and East and

Central Africa, Clare’s research focuses on developing practice-based evidence on the change potentials

of people, organisations, and institutions using ethnographic, qualitative, and participatory methods.

Clare holds a PhD in Social Psychology from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and

an MSc in International Primary Health Care and BSc in Human Sciences, both from University College

London.

Dr Alexis Karamanos is a Population Health Analyst for the London Borough of Hackney and the City

of London, and a visiting Research Associate in Social Epidemiology and Public Health at King’s College

London. He is interested in the social, economic, and political determinants of human development, and

health inequalities over the life course. Alexis holds an undergraduate degree in Political Science and

Public Administration from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. He also holds

an MSc in Health and Society: Social Epidemiology from University College London (UCL), which was

funded by the Onassis Foundation, and a PhD in Population Health from UCL which was funded by the

UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

5

Foreword

The Zero HIV Social Impact Bond was the Elton John AIDS Foundation’s response - despite excellent

clinical care within the health system - to the seemingly intractable problem of continued undiagnosed/

late HIV diagnosis in England. When I first started talking back in 2015 with interested people from

Lambeth council, NHS England, and NHS clinical colleagues about the potential of creating the world’s

first ever HIV SIB to expand testing and linkage to care, I was confident that we could make an impact.

But what an impact! Over 460 people have been either newly diagnosed with HIV or reengaged into care

across South London, providing access to lifesaving treatment, preventing onward transmission of HIV,

and avoiding over £90m of costs to the healthcare system.

Our partnership with Terrence Higgins Trust and National Aids Trust in developing the HIV Commission,

so ably chaired by Dame Inga Beale, gave a great opportunity for us to share the learning from the SIB.

The HIV Commission 2020 report emphasised the importance of HIV testing at every opportunity. In

response the government committed to develop the HIV Action Plan, giving us the chance to lay out our

evidence to DHSC and the Action Plan taskforce. The HIV Action Plan, launched by the Dept of Health

last December, committed £20m for the roll out of opt out ED HIV testing in very high areas of HIV

incidence, the first new HIV funding in many years, as well as annual reporting of progress to Parliament.

As this service evaluation shows, we now have the evidence that opt out ED and primary care HIV

testing reaches those members of the community who do not currently come into contact with HIV

testing services anywhere else. In particular the SIB highlighted inequities for rates of diagnosis and

reengagement in care for minority groups and amongst women and older people We were able to

contextualise this data against related health and social care needs, thus informing broader planning

for service delivery by Integrated Care Systems and local authorities. The SIB also highlighted missed

6

opportunities for new HIV diagnoses and the critical need to reengage many patients living with HIV

who are Lost to Follow Up. SIB partners reengaged over 250 people back into treatment, improving their

health and wellbeing, avoiding potentially expensive hospital treatment, and contributing to the HIV

Commission goal of Zero HIV transmissions by 2030.

As you will see, the SIB approach itself brought benefits. Its structure allowed for considerable flexibility

and innovation by implementing partners, matched as it was with the reassurance of upfront payments.

A laser focus on outcomes saw greater collaboration across dierent clinical teams and the creation of

HIV GP Champions energised opt out testing services in primary care. It has been truly heart-warming

to hear this feedback which underscores the importance of collaboration and consensus across

stakeholders.

I would like to thank our partners in the hospitals, primary care and community organisations for their

amazing work; our funding partner The National Lottery Community Fund, our investors from Comic

Relief, Big Issue Invest and Viiv Healthcare; and commissioners in the Public Health teams at Lambeth,

Southwark and Lewisham councils; the team at NHS England and Public Health England (in their

new homes at UKHSA and OHID), the legal team at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer for their pro bono

support and Maclaren Consulting for developing our PowerBI management and reporting system.

We are deeply grateful to all those involved in the project and those who have created this evaluation

report. We look forward to a national roll out to continue this vital work.

Anne Aslett

Chief Executive Ocer of the Elton John AIDS Foundation

March 2022

7

Executive Summary

This service evaluation takes a combined qualitative and quantitative methodological approach to

explore an innovative public health intervention with significant public management implications in

South London. The intervention is known as the ‘Elton John AIDS Foundation Zero HIV programme’ (we

term it the Zero HIV SIB programme in this report). The intervention ran in the boroughs of Lambeth,

Southwark, and Lewisham from November 2018 until the end of December 2021. The goals of the

intervention include improving a person living with HIV’s health outcomes by linking them into HIV

treatment either as a new diagnosis or through re-engagement with NHS services (if already diagnosed

but not receiving treatment) before their condition deteriorates, slowing the spread of HIV through

avoiding future transmission and saving the NHS money in future years.

The intervention was financed through a novel Social Impact Bond (SIB) mechanism. A SIB is an

outcomes-based contract, in which a commissioner pays a contractor for certain measurable outcomes.

A key facet of the SIB approach is to encourage multi-agency collaboration across public, private, and

philanthropic partners (Carter et al, 2020). A deeper understanding of these collaborations – how they

work, their strengths and weaknesses – is very important for informing wider commissioning decisions

not only in HIV but across other chronic diseases.

We find that the 3-year Zero HIV SIB programme has been eective in both (1) delivering improved

health outcomes for people living with HIV and (2) improving inter-organisational collaboration and

service collaboration across what has historically been a rather fragmented HIV healthcare ecosystem in

South London.

In terms of the health impacts, key actors expressed confidence that this programme had reached (i)

people living with HIV who were previously undiagnosed and brought them into contact with specialist

NHS services and (ii) people living with HIV who were previously diagnosed but had become ‘lost to

follow-up’ (LTFU) treatment services. However, the absence of robust baseline data for key outcomes

or a commitment to a counterfactual evaluation design means it is not possible to attribute outcomes to

specific interventions.

Data from EJAF show that 124 new HIV diagnoses were identified through ED testing, and 53 LTFU

patients were also identified through participating EDs in South London hospitals. These hospitals also

re-engaged a further 153 LTFU patients separate to ED testing. Primary Care providers identified 26 new

HIV diagnoses through GP testing and also re-engaged 45 LTFU patients. Finally, 46 new diagnoses were

made by community providers and 5 LTFU patients were re-engaged by community providers as part of

the Zero HIV programme.

In terms of the organisational impacts, key actors expressed confidence that this programme

successfully mitigated many of the traditional organisational and financial factors that had led

to fragmented HIV services in South London through (i) improved inter-organisational network

working – both formal and informal in nature through boundary spanning activities and a pervading

‘cosmopolitanism’ (Greenhalgh et al, 2004; Damschroder et al, 2009). In addition to this, informants

perceived the increased use of data and monitoring and the realignment of incentives as positively

promoting collaboration and better outcomes. In terms of financing (ii) the programme very eectively

8

negated many aspects of the existing siloed payments systems for various aspects of HIV services which

actors felt had stymied attempts for providers to implement evidence-informed practice (for instance

in relation to ED and Primary Care testing), or to adapt to practical realities (such as identifying LTFU

patients and providing more flexibility for not-for-profit provider organisation outreach work).

The programme adapted and grew over the three years with new provider organisations recruited

over the lifetime of the programme and new emphases on delivery developed – for example through

the expanded use of GP champions. This adaptability proved to be very beneficial in relation to the

COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 (see Stanworth, 2022) and presaged a pivot to greater LTFU work.

Community providers welcomed the flexibility that the programme aorded them overall, though issues

were noted by some providers in relation to how SIB-financed work may have been seen to duplicate

existing work commissioned more conventionally.

The role of EJAF was praised by informants. The organisation played a key boundary spanning function

and delivered leadership, support, and encouragement to other organisations. EJAF were crucial

players in the design, financing, and delivery of the programme acting as co-commissioners, financial

intermediaries, project managers, and data analysts. EJAF successfully disrupted many of the existing

inter-organisational, financial, and institutional barriers that historically inhibited more systematic

implementation of testing, LTFU and better joined-up HIV service provision. EJAF were instrumental

in shaping an ‘outer context’ (Damschroder et al, 2009) conducive to improving HIV services in South

London.

Rather than one ‘intervention’ the qualitative data in this report highlight that the actors involved

in commissioning and delivering HIV services through the Zero HIV SIB programme felt they were

delivering a suite of ‘interventions’. Some of these have a strong existing evidence base and have been

recommended in existing guidelines whilst others are more organisational and pragmatic. Some were

new and developed as part of the Zero HIV SIB programme whilst others were already in existence in

some or other settings. A key finding is increased flexibility and local discretion to use funds to tailor

services more closely to the needs of those using services as we have seen in other health focused SIBs

in the UK (Fraser et al, 2018).

A central aim of the Zero HIV SIB programme was to further the evidence for these interventions and

change practice going forward. A criticism of the programme raised by some informants was that more

work could have been done to ‘baseline’ existing practice and prove the attribution of some of these

interventions in order to provide a more robust body of evidence to sustain these going forward once the

SIB financing ended in December 2021. Though beyond the scope of this current service evaluation, it

appears that learning from the programme (particularly in relation to ED testing) may have been used to

inform national and local level policymakers in future HIV policy development.

There are mixed views from informants in relation to the sustainability of the improvements to South

London HIV services delivered through the Zero HIV SIB programme after the SIB-financing is gone.

More research is needed to follow these developments over the coming years.

9

Introduction

This service evaluation takes a combined qualitative and quantitative methodological approach to

explore an innovative public health intervention with significant public management implications in

South London. The intervention is known as the ‘Elton John AIDS Foundation Zero HIV programme’. The

goals of the intervention include improving a person living with HIV’s health outcomes by linking them

into HIV treatment either as a new diagnosis or through re-engagement with NHS services (if already

diagnosed but not receiving treatment) before their condition deteriorates, slowing the spread of HIV

through avoiding future transmission and saving the NHS money in future years. It was developed by

the Elton John AIDS Foundation, in partnership with Lambeth local authority and NHS England, and

received support from the National Lottery Community Fund. The intervention ran in the boroughs of

Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham from November 2018 until the end of December 2021.

The intervention was financed through a novel Social Impact Bond (SIB) mechanism. It was the first

SIB in the world to focus on HIV treatment and care. A SIB is an outcomes-based contract, in which a

commissioner pays a contractor for certain measurable outcomes. The outcomes (diagnosing new cases

of HIV and re-engaging patients who dropped out of HIV care) have significant beneficial social impacts as

well as hypothetical cost-savings for the NHS. A key facet of the SIB approach is to encourage multi-agency

collaboration across public, private, and philanthropic partners (Carter et al, 2020). A deeper understanding

of these collaborations – how they work, their strengths and weaknesses – is very important for

informing wider commissioning decisions not only in HIV but across other chronic diseases.

This service evaluation is informed by an Implementation Science approach (Damschroder et al,

2009) to explore the impacts and implications of the Zero HIV programme from the perspectives of

service users, clinical sta, health service managers, local authority commissioners, private sector, and

10

philanthropic stakeholders. The evaluation also explores questions in relation to the sustainability of the

intervention beyond the end of the SIB financing in December 2021.

The overall objective of the evaluation is to learn more about the processes, impacts and sustainability

of the Zero HIV intervention through combined research methods. These principally include semi-

structured interviews with individuals who receive the services through the intervention, those who

deliver the intervention, those who design and oversee the intervention, those who commission the

intervention, and those who have provided finance for the intervention. Alongside interviews, the

evaluation also draws on relevant documentary sources and anonymized descriptive statistical information.

The qualitative element of the evaluation focuses on the following research questions:

1. What do key stakeholders perceive to be the organisational and health impacts of the

Zero HIV intervention?

2. Through what mechanisms, how, and why, does the Zero HIV intervention impact upon the

behaviour, attitudes, and actions of:

(a) Service users?

(b) NHS and non-NHS providers?

(c) NHS and Local Authority commissioners?

(d) Wider stakeholders including those involved in financing, evaluating, and overseeing the Social

Impact Bond element of the intervention?

3. How might these impacts and behaviour changes be sustained:

(a) In South London after the SIB financed programme ends in December 2021?

(b) And/or transferred to other geographical settings?

The quantitative element of the evaluation focuses on the following research questions:

1. Are there any ethnic, sex and age dierences in the likelihood of being diagnosed?

2. Are there any ethnic, sex and age dierences in the likelihood of being re-engaged?

3. Are there any ethnic, sex and age dierences in the likelihood of non-engagement in treatment (e.g.,

found through ED testing “non-contactable,” or even re-attending at ED)?

The current report will provide an overview of the key responses to these research questions. Further

analysis will be performed on the data collected leading to submissions of papers to academic journals.

It is anticipated that the research team will conduct further research in South London in order to explore

qualitative research question 3 (a) above more fully. The current report does not directly evaluate the

impact and eectiveness of the SIB financing mechanism as this is explicitly evaluated by another

research team led by Ecorys and ATQ (see Stanworth, 2020; 2022). However, the report does explore

some of the links of how the financing mechanism impacts upon the delivery of the health interventions.

This report does not explore the cost-eectiveness or health economic impacts of the programme.

11

Methodological and theoretical approach

Qualitative approach

This service evaluation follows a case study approach (Yin, 2009; Eisenhardt, 1989) to explore

the perceptions of key actors in relation to the nature, impacts and sustainability of the Zero HIV

intervention. A qualitative case study approach is appropriate for exploring issues related to policy

implementation (Fraser & Mays, 2020), exploring ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions about phenomena

through detailed contextualised accounts of a case (Yin, 2009). Interviews were conducted until “data

saturation” (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) and were recorded, translated, transcribed, and coded using

NVivo 12. Members of the research team discussed and reviewed the interview data alongside relevant

documentary material to ensure consistency.

We conducted 31 interviews overall, principally through the Summer and Autumn of 2021. Most

interviews took place via MS Teams given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We purposively sampled

informants to a wide selection of relevant viewpoints. Most interviews lasted an hour. We used an

interview schedule that asked informants about their professional background, work history, and asked

them to provide an overview of their understanding of the Zero HIV intervention and the barriers and

facilitators linked to this. We discussed prospective opportunities and challenges faced in the roll-out

and development of the intervention whilst allowing informants the space to express their own narratives

(Fontana and Frey, 2000).

Table 1: Interview informant data

Role Number of

informants

Number of organisations

represented

Community organisation outreach worker (strategic,

operational, and patient-facing responsibilities)

4 4

SIB investor 2 2

GP (HIV champions) 3 3

HIV patient 2 N/A

EJAF (strategic, operational and data management

responsibilities)

4 1

NHS hospital sta (including nurses, doctors, managers,

both HIV and non-HIV specialists – e.g. A&E sta)

9 3

Project evaluator 1 1

Local commissioners (CCG and/or LA) 4 2

National commissioners 2 2

The data were interrogated repeatedly in order to understand key emergent issues drawing on the

principles of ‘constant comparison’ (Glaser, 1965). The analytical approach drew on both inductive

and deductive reasoning (Langley, 1999) – exploring emergent issues alongside insights from wider

implementation science theory (Damschroder et al, 2009). Whilst “recall bias” may be a problem in

relation to retrospective interviews with some stakeholders, retrospective interviews can also have

benefits – such as encouraging informants to critically appraise the original rationale for decisions

relating to policy and practice.

12

Quantitative approach

Data

In this secondary data analysis, we use data from 2,388 individuals aged 15 and over in 29 London

borough councils between August 2018 and December 2021.

Outcome

The outcome of interest includes information for individuals who were known positive (N=1,512) during

the study period. This forms the baseline category of this analysis against which information from other

categories is compared. These categories are formed by those who were newly diagnosed (N=223),

those who were re-reengaged to treatment (N=249) and those who were not being able to be contacted

(N=121). There was missing information on the outcome of interest for 257 individuals.

Demographic variables

Information on sex and age categories (35-49 years was used as the reference category) was used.

UK Health and Security (UKHSA), formerly known as Public Health England, ethnic categorisation

information was also used (White, Black African, Black Caribbean, Black other, Asian, and Mixed).

Information on London borough council residence was collapsed to four categories (Lambeth, Lewisham,

Southwark and Other) since ~80% of the sample was from Lambeth, Lewisham, and Southwark.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive reasons, we first explored the probability of each outcome category by age and

ethnicity. Further, we applied multivariable multinomial logistic regression modelling to identify

characteristics that have a greater probability of being newly diagnosed, re-engaged with treatment

and being non-contactable compared to those who were known positive. Particularly, the ratio of the

probability of being newly diagnosed or re-engaged with treatment or not being able to be contacted

over the probability of being known positive (baseline category) is expressed as relative risk. When a

characteristic/variable has a relative risk ratio (RRR) of one, this means there is neither an increase nor

a decrease in the probability of choosing one of the modelled outcome categories compared with the

baseline category. A RRR greater than one indicates an increased probability of choosing one modelled

outcome category compared with the baseline category. A RRR lower than one indicates a decreased

probability of choosing one modelled outcome category compared with the baseline category. We opted

for a single model, which produces the most accurate representation of the eect of each of the core

demographic (age, sex, Ethnicity and London borough council) characteristics on the probability of being

newly diagnosed or being re-engaged with treatment or being able to be contacted relative to being known

positive. It is worth mentioning that we decided not to adjust for the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD-a

measure highlighting area deprivation) since most of our sample comes from economically deprived areas

(more than 70% of the sample comes from the top 30% of area deprivation).

13

Ethics

We submitted our study protocol for review by the Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

Research & Development governance team in March 2020. They recommended our work be defined

as a ‘service evaluation’ and advised that it therefore did not need formal IRAS/NHS ethical approval.

Where appropriate we secured site specific NHS R&D approval for the qualitative elements of the

service evaluation. All participants in the qualitative part of the research received detailed participant

information sheets and were formally asked for consent before taking part.

In addition, we developed a formal data use agreement between KCL and EJAF to ensure robust

governance in relation to the use of quantitative data for this report and subsequent academic outputs.

Theoretical approach

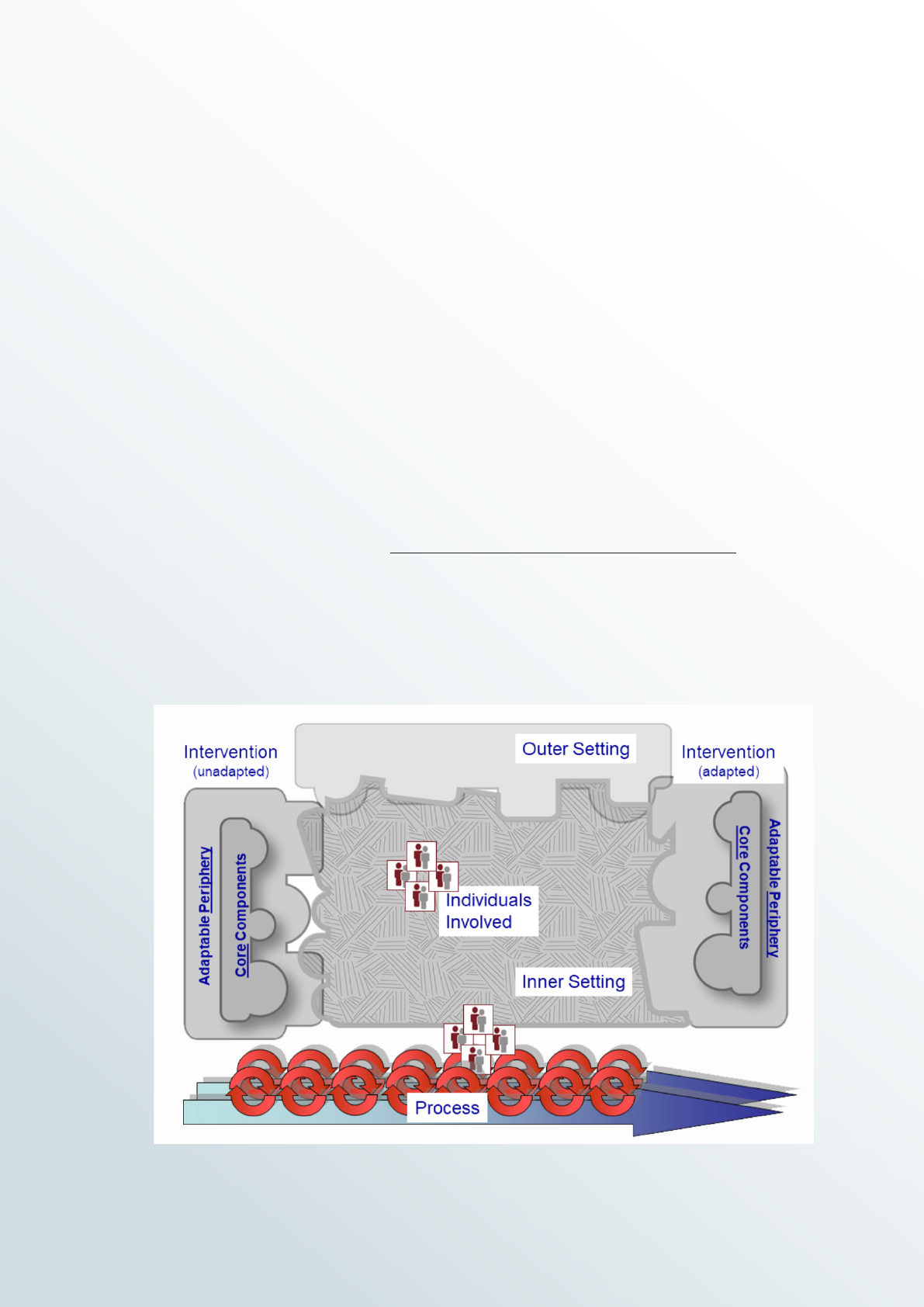

Our study design is influenced by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)

framework pioneered by Laura Damschroder and colleagues (Damschroder et al, 2009). The CFIR is

structured around five ‘constructs’. These are (1) intervention characteristics (2) outer setting (3) inner

setting (4) characteristics of individuals (5) implementation processes.

Figure 1: The CFIR

14

The qualitative data generated by the service evaluation interviews were analysed using key components

drawn from the CFIR. This enabled a clear and theoretically informed framework to interrogate:

1. the characteristics of the intervention (or interventions) developed as part of the Zero HIV

programme by dierent actors over time and across dierent settings

2. the wider financial, strategic, and operational context developed to coordinate the intervention(s)

3. the dierent relationships and interactions at the micro-level focused on delivery of the

intervention(s)

4. the importance of key personal characteristics of individuals designing, delivering, or monitoring the

intervention(s)

5. the important processes involved in promoting and/or inhibiting the delivery of the intervention(s).

Future academic outputs will explore these five constructs in greater detail than we do in this current

report – however the analyses included here are driven by key CFIR ideas. It is also worth noting

some important inductive codes not covered by the CFIR. This included definition of the Zero HIV SIB

programme interventions, the impact of COVID-19, HIV stigma, and issues related to post-SIB-financing.

15

Zero HIV SIB programme background

This service evaluation explores important Public Health and Public Management questions. In relation

to Public Health, the service evaluation reflects if and how the Zero HIV intervention reached hard-to-

reach populations with HIV – either those who have never been tested or who have stopped attending

treatment. This work has important implications for health equity. We know that anti-retroviral therapy

(ART) for those with HIV is highly eective enabling individuals to live long and healthy lives. There

are massive benefits to individuals if they can be diagnosed and start to receive treatment, but Public

Health England (PHE) estimates that about 6% of the 105,200 people living with HIV are unaware of

their condition (PHE, 2019). The earlier that diagnosis occurs the better, as over time the undiagnosed

virus may damage the immune system and general health. PHE data show that 43% of those diagnosed

in 2018 were diagnosed late, with late diagnosis being much higher among certain groups (PHE,

2019). Beyond the individual health benefits of early diagnosis and ongoing treatment of HIV there are

significant wider public health benefits as eective treatment reduces the risk that the infected person

can pass on the virus to almost zero. These individual and population level health benefits may also

be expected to have wider financial benefits for the health system by keeping those with HIV healthy

and also reducing the likelihood of further onward transmission of the disease. As Stanworth (2022)

highlights – whilst there is no recent independently validated estimate of the scale of such benefits,

calculations made by the Elton John AIDS Foundation suggest that they amount to an estimated

£220,000 per person, based on £140,000 of cost avoided through treatment, and £80,000 avoided by

reduced onward transmission.

In relation to Public Management, a key interest here is the novel Social Impact Bond (SIB) financing

mechanism. This is the first SIB in the world to focus on HIV treatment and care. SIBs are hugely

interesting from a public policy and management perspective (Fraser et al, 2018) sitting at the vanguard

of policies designed to foster an outcomes-based focus in public service commissioning and delivery

(Edmiston & Nicholls, 2018). A key facet of the SIB approach is to foster multi-agency collaboration

across public, private, and philanthropic partners (Blundell et al, 2019). The Zero HIV programme brings

together the Elton John AIDS Foundation, Lambeth Council, Southwark Council, Lewisham Council, NHS

England, NHS Improvement the National Lottery Community Fund, ViiV Healthcare, Comic Relief, and

Big Issue Invest to work with local NHS Trusts, Primary Care and Community providers to collaboratively

tackle problems related to people living with undiagnosed HIV across Lambeth, Southwark, and

Lewisham. A deeper understanding of these collaborations – how they work, their strengths and

weaknesses – is very important for informing wider commissioning decisions not only in HIV but for

other chronic diseases too.

16

Findings

Evaluating the impact of the Zero HIV programme

We firstly present an overview of the impact of the Zero HIV programme through a series of textboxes

and discuss some of the key quantitative findings before moving on to the qualitative findings of the

service evaluation.

ED TESTING IMPACTS

124 people were diagnosed with HIV and linked to care, and a further 53 people living with HIV

were reengaged into care following ED HIV testing. Of these 55% were Black African, Black

Caribbean or Black Other community members, which when compared with the 22% of new

diagnoses from these communities reported in the Public Health England ‘London HIV Spotlight’

(2018) (Black African, Black Caribbean data only), suggests that ED HIV testing is extremely

good at reaching communities who may not otherwise be tested, either through not using

services where HIV testing is oered, or by avoiding testing through fear of HIV stigma. Late

outcomes (CD4 count <350) were 74% of new diagnoses and 81% of reengagements, suggesting

that ED HIV testing is finding people who are at serious risk of needing extensive treatment and

developing AIDS defining diseases and linking them to care.

ED HIV testing has a health inequalities element, with 50% of all those newly diagnosed living in

areas within the two lowest deciles of the Index of Multiple deprivation see figure 2.

(Data from EJAF)

17

Figure 2: Patient Total by Ethnicity, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) Decile

(where 1 is most deprived 10% of LSOAs) (bins) (groups)

LTFU WORK BY HOSPITALS

A total of 153 people were reengaged through hospital HIV clinic recall work. 71% were from

Black African, Black Caribbean and Black Other communities, which suggests that LTFU work is

particularly helpful in reaching people from this community, who may have left care because of

HIV stigma as well as other life challenges. For the LTFU group as a whole, 53% had a CD4 count

of <350, suggesting that this is a cohort of people who were at risk of serious illness and expensive

utilisation of hospital resources.

(Data from EJAF)

Not known &

Not stated

Other

White &

White other

Black African &

Black Carribean

& Black other

54.0%

57.1%

61.1%

33.3%

66.7%

33.3%

33.3%

28.6%

27.8%

9.5%

21.0

3 4 5 6 7 81 & 2

50.0

18.0

9.0

3.0

2.0

1.0

24.0%

14.0%

8.0%

18

As can be seen in figure 3, the risk of LTFU is highly correlated with where someone lives and using the

Index of Multiple Deprivation suggests that this work is highly eective in engaging those people who are

already experiencing significant health inequalities (data from EJAF).

Figure 3: Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) Decile (where 1 is most deprived 10% of LSOAs) (bins)

(groups)

Asian

Other

White &

White other

Black African &

Black Carribean

& Black other

74.0%

72%

10%

20%

10%

7%

29

72%

67%

33%

9

25

67%

40%

40%

3 4 5 7 61 & 2

19.0%

7.0%

68

PRIMARY CARE NEW DIAGNOSES AND LTFU

36 new diagnoses, and 45 reengaged patients were identified through testing and LTFU work done

by the primary care providers involved in the programme.

(Data from EJAF)

19

IMPACT OF COMMUNITY ORGANISATIONS

This intervention led to 46 people being newly diagnosed, and 5 people being reengaged into

care. Providers that targeted Latin American community members were especially successful

contributing 32 new outcomes and one reengagement, suggesting that this is a community that is

particularly underserved through current arrangements.

(Data from EJAF)

Bringing these data together, there are a number of points we can make about the impact of the Zero

HIV programme. Firstly, in terms of the age of people living with HIV identified in the programme we

may say the following. Older participants identified by the programme were more likely to be known

to be HIV positive. Those aged 15-34 years were more than twice as likely to be newly diagnosed as

SIB participants aged 35-49 and 50 years and over. Participants aged 35-49 years were more likely to

be re-engaged to care than participants aged 15-34 years and 50 years and over. There was a higher

probability of not being able to be contacted for participants aged 15-34 years than older participants,

however 95% confidence intervals slightly overlapped (this is probably due to the small sample of SIB

participants who could not be contacted).

20

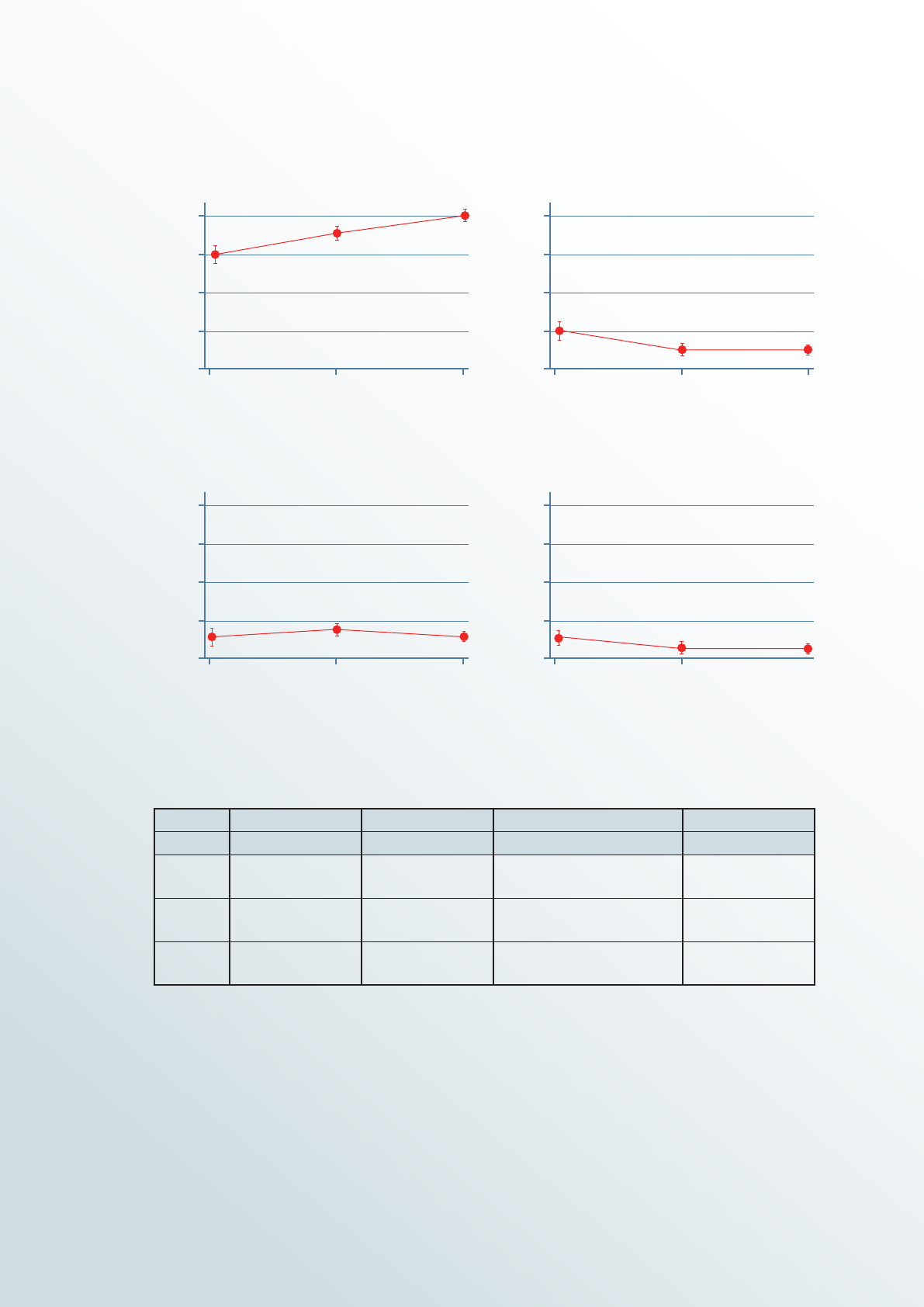

Table 2: Unadjusted predicted probabilities of outcomes by age group

Known positive New diagnosis Re-engagement to care Non-contactable

Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI]

15-34

0.61

[0.56, 0.67]

0.20

[0.16, 0.25]

0.10

[0.07, 0.13]

0.09

[0.06, 0.12]

35-49

0.7

[0.67, 0.73]

0.1

[0.07, 0.11]

0.16

[0.13, 0.18]

0.05

[0.03, 0.06]

50+

0.78

[0.75, 0.80]

0.08

[0.07, 0.10]

0.09

[0.07, 0.11]

0.05

[0.04, 0.06]

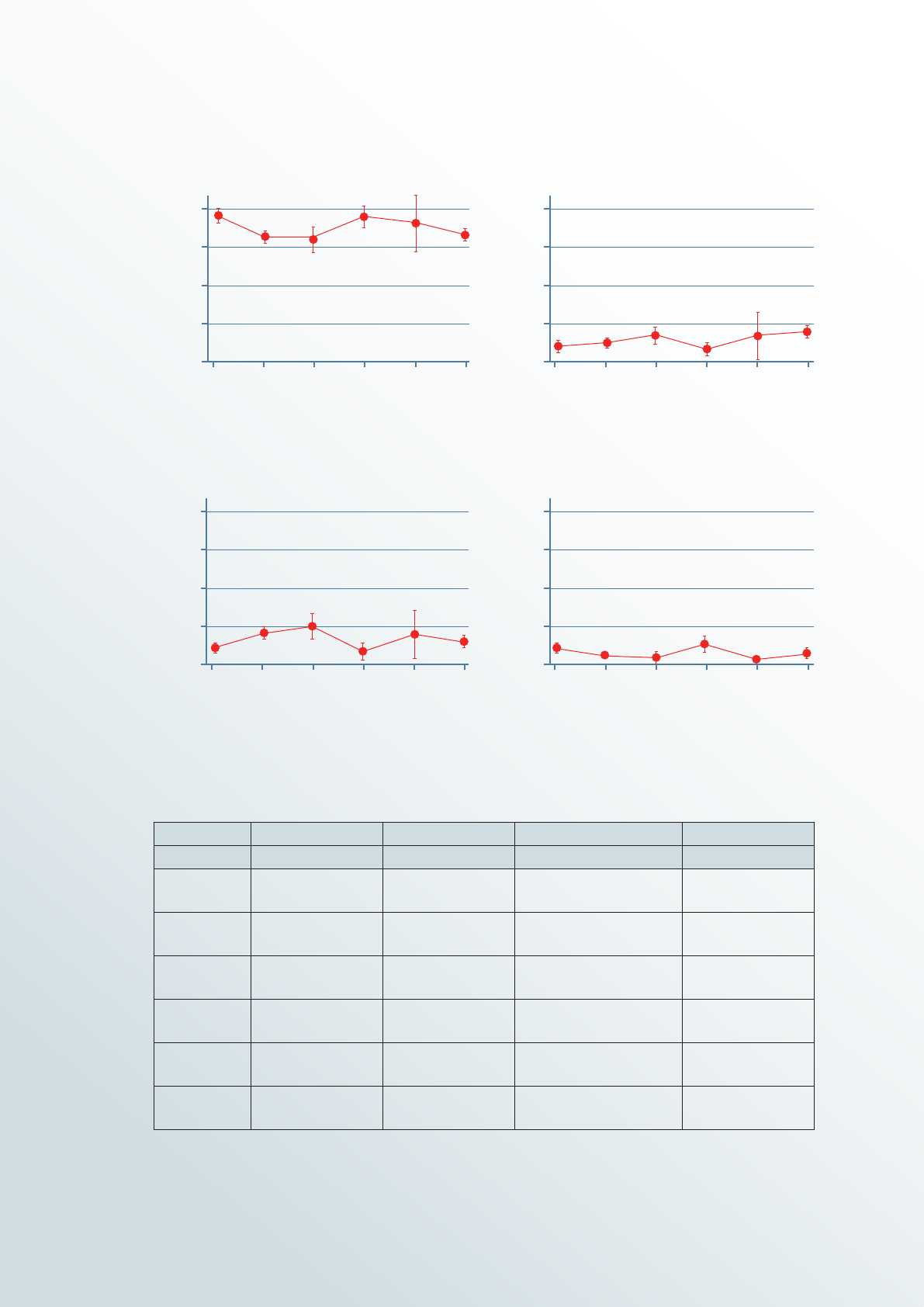

In terms of ethnicity, our data suggest the following. White participants in the programme had a

significantly higher probability of being known to be HIV positive than Black African, Black Caribbean

and Other/Mixed. Black Caribbean and Black African participants had a higher probability of being newly

diagnosed than White participants, nevertheless 95% confidence intervals were overlapping (indicating

uncertainty about the statistical significance of these probability dierences). Black African and Black

Caribbean participants were two and three times as likely to be re-engaged to HIV care as White

participants. Black African and Black Caribbean participants had a lower probability of not being able to

be contacted, however 95% confidence intervals were overlapping slightly.

Figure 4: Unadjusted predicted probabilities of outcomes by age group

15-34

15-34

15-34

15-34

35-49

35-49

35-49

35-49

Age group

Age group

Age group

Age group

50+

50+

50+

50+

Probability of being known positive by age with 95% CIS

Probability of re-engagement by age with 95% CIS

Probability of new diagnosis by age with 95% CIS

Probability of non-contact by age with 95% CIS

80

80 80

80

60

60 60

60

40

40 40

40

20

20 20

20

0

0 0

0

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

21

Table 3: Unadjusted predicted probabilities of outcomes by UKHSA ethnic categorisation.

Known positive New diagnosis Re-engagement to care Non-contactable

Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI]

White 0.77

[0.72, 0.81]

0.09

[0.06, 0.12]

0.079

[0.05, 0.11]

0.07

[0.04, 0.10]

Black African 0.67

[0.63, 0.71]

0.12

[0.10, 0.15]

0.17

[0.139, 0.199]

0.04

[0.02, 0.05]

Black

Caribbean

0.63

[0.56, 0.71]

0.13

[0.07, 0.18]

0.22

[0.15, 0.28]

0.03

[0.01, 0.05]

Black other 0.75

[0.68, 0.83]

0.07

[0.02, 0.11]

0.08

[0.04, 0.13]

0.10

[0.05, 0.15]

Asian 0.71

[0.55, 0.87]

0.13

[0.01, 0.25]

0.16

[0.03, 0.29]

9E-08

Other/Mixed 0.68

[0.64, 0.72]

0.15

[0.12, 0.19]

0.10

[0.07, 0.13]

0.06

[0.04, 0.09]

Figure 5: Unadjusted predicted probabilities of outcomes by UKHSA ethnic categorisation.

White

White

White

White

Black African

Black African

Black African

Black African

Black Caribbean

Black Caribbean

Black Caribbean

Black Caribbean

Black other

Black other

Black other

Black other

Asian

Asian

Asian

Asian

Other/mixed

Other/mixed

Other/mixed

Other/mixed

80

80 80

80

60

60 60

60

40

40 40

40

20

20 20

20

0 0

0 0

UKHSA Ethnic Category

UKHSA Ethnic Category

UKHSA Ethnic Category

UKHSA Ethnic Category

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

Probability of being known positive by ethnicity with 95% CIS

Probability of re-engagement by ethnicity with 95% CIS

Probability of new diagnosis by ethnicity with 95% CIS

Probability of non-contact by ethnicity with 95% CIS

22

Table 4: Unadjusted predicted probabilities of outcomes by London borough council.

Known positive New diagnosis Re-engagement to care Non-contactable

Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI] Pr [95% CI]

Lambeth

0.79

[0.76,0.82]

0.06

[0.04, 0.08]

0.11

[0.08, 0.13]

0.04

[0.03, 0.06]

Lewisham

0.67

[0.66, 0.74]

0.12

[0.09, 0.15]

0.15

[0.12, 0.19]

0.02

[0.01, 0.04]

Southwark

0.77

[0.74, 0.80]

0.10

[0.08, 0.13]

0.07

[0.05, 0.09]

0.06

[0.04, 0.07]

Other

0.60

[0.55, 0.65]

0.16

[0.13, 0.20]

0.16

[0.12, 0.17]

0.08

[0.05, 0.11]

Lambeth Lambeth

Lambeth Lambeth

Southwark Southwark

Southwark Southwark

Lewisham Lewisham

Lewisham Lewisham

London Borough London Borough

London Borough London Borough

Other Other

Other Other

Probability of being known positive by council with 95% CIS Probability of new diagnosis by council with 95% CIS

Probability of re-engagement by council with 95% CIS Probability of non-contact by council with 95% CIS

Figure 6: Unadjusted predicted probabilities of outcomes by London borough council.

In terms of the geographical distribution of those identified as either new diagnoses or as LTFU patients,

the data suggest that participants in Lewisham and other London borough councils had a significantly

lower probability of being known to be HIV positive than SIB participants in Lambeth and Southwark.

Participants in Lambeth had a significantly lower probability of being newly diagnosed than other borough

councils, and finally, participants in Lewisham and other London borough councils had a significantly

higher probability of being re-engaged to care than SIB participants in Lambeth and Southwark.

80

80 80

80

60

60 60

60

40

40 40

40

20

20 20

20

0

0 0

0

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

PR (Outcome == Known_Positive)

Percent

23

We also conducted multivariable multinomial logistic regression by demographic characteristics and

can state that after mutual adjustment of demographic characteristics, it was observed that the relative

risk of a female is RRR=.68 for being newly diagnosed vs. being a known positive. In other words, the

expected probability of being newly diagnosed was significantly lower for females (32%). The expected

probability of being newly diagnosed was significantly higher for those aged 15-34 compared to those

aged 35-49 years old. Black Africans were twice and Black Caribbeans almost three times as likely as

White British to be newly diagnosed. Participants in the SIB from other/mixed ethnic background were

twice as likely as White British to be newly diagnosed. Newly diagnosed patients with HIV were more

likely to be found in Lewisham (almost 3 times), Southwark (almost 2 times) and other borough council

(4 times) compared to Lambeth.

After mutual adjustment of demographic characteristics, it was observed that the expected probability

of being re-engaged was 51% higher for females compared to males. The expected probability of being

re-engaged was 44% lower for those aged 50-64 years and 77% for those aged 65 and over compared to

those aged 35-49 years. Black Africans were almost twice and Black Caribbeans more than three times

as likely as White British to be re-engaged. Participants in the Zero HIV programme were more likely to

be re-engaged in Lewisham or another borough council compared to Lambeth. The probability of being

re-engaged is not statistically dierent for Southwark and Lambeth.

After mutual adjustment of demographic characteristics, it was observed that the expected probability

of not being able to be contacted was 71% higher for females. The expected probability of not being

able to be contacted was 53% lower for those aged 35-49 compared to those aged 15-34 years. Black

Africans and Black Caribbeans had a lower probability of not being able to be contacted compared to

White British. However, these dierences were not statistically significant. This is possible due to the

small number of those who could not be contacted. Compared to Lambeth, participants in other borough

councils were more likely to not being able to be contacted. The probability of not being able to be

contacted was similar for participants in Lambeth, Southwark, and Lewisham.

24

Table 5: Multivariable multinomial logistic regression by demographic characteristics (probabilities

expressed as relative risk ratios-an RRR below 1 indicates a lower probability, above 1 indicated a higher

probability).

New Diagnosis Re-engagement to care Non-contactable

RRR [95% CI] RRR [95% CI] RRR [95% CI]

Gender

Male Ref. Ref. Ref.

Female 0.70* [0.49,0.99] 1.51* [1.10,c2.07] 1.71* [1.04,2.84]

Age

15-34 Ref. Ref. Ref.

35-49 0.44*** [0.3.0,0.67] 1.28 [0.80,2.04] 0.47* [0.24,0.93]

50+ 0.349*** [0.23,0.52] 0.67 [0.41,1.07] 0.63 [0.34,1.17]

Ethnicity

White Ref. Ref. Ref.

Black African 1.98** [1.21,3.25] 1.872* [1.152,3.042] 0.532 [0.270,1.050]

Black Caribbean 2.60** [1.37,4.94] 3.295*** [1.843,5.888] 0.359 [0.102,1.264]

Black other 0.90 [0.41,2.02] 0.858 [0.403,1.829] 1.339 [0.619,2.895]

Asian 1.47 [0.46,4.74] 1.494 [0.502,4.445] 0.000 [0.000,0.000]

Other/Mixed 1.97** [1.21,3.2.0] 1.245 [0.744,2.084] 0.897 [0.472,1.702]

Council

Lambeth Ref. Ref. Ref.

Lewisham 2.70*** [1.67,4.36] 1.94** [1.29,2.92] 0.47 [0.22,1.02]

Southwark 1.85* [1.13,3.02] 0.84 [0.53,1.33] 1.04 [0.57,1.91]

Other 4.13*** [2.53,6.77] 2.82*** [1.81,4.37] 1.89* [1.01,3.51]

There are limitations to these data that must be considered. Firstly, the small sample size of those

re-engaged to care and those who decided not-to re-engage does not allow a detailed exploration

of any ethnic, sex and age dierences in the odds of being re-engaged into HIV care by HIV clinics

and GP practices. Secondly, the small number of counts (sample size) does not allow to explore how

the demographics of people disconnected from care & reached through HIV clinic or primary care

audit/recall interventions dier from those found through ED testing or another route. Finally, most

participants lived in more socio-economically deprived neighbourhoods, therefore there was limited

statistical power to explore inequalities in HIV care in SIB at the intersection of socio-economic

disadvantage and demographic characteristics.

25

Evaluating the processes through which

the Zero HIV programme functioned

The qualitative findings of the service evaluation are structured as follows.

› Firstly, we provide a narrative overview of the programme and combine headline descriptive

statistics with a synthesis of key qualitative data.

› Secondly, we define the distinct elements of the Zero HIV ‘intervention’ and reflect on the ways in

which dierent actors define these.

› Thirdly, we explore the dierent intervention elements across their separate healthcare settings in

three subsections – secondary care (hospitals), primary care (GP practices), and the community.

› Fourthly, we present the views of participants in relation to the sustainability of these HIV service

interventions beyond the period of SIB-financing.

Narrative overview

The headline finding from this service evaluation is that the 3-year Zero HIV SIB programme has been

eective in both (1) delivering improved health outcomes for people living with HIV and (2) improving

inter-organisational collaboration and service collaboration across what has historically been a rather

fragmented HIV healthcare ecosystem in South London.

In terms of the health impacts, key actors expressed confidence that this programme had reached (i)

people living with HIV who were previously undiagnosed and brought them into contact with specialist

NHS services and (ii) people living with HIV who were previously diagnosed but had become ‘lost to

follow-up’ (LTFU) treatment services. However, the absence of robust baseline data for key outcomes

or a commitment to a counterfactual evaluation design means it is not possible to attribute outcomes to

specific interventions.

In terms of the organisational impacts, key actors expressed confidence that this programme

successfully mitigated many of the traditional organisational and financial factors that had led

to fragmented HIV services in South London through (i) improved inter-organisational network

working – both formal and informal in nature through boundary spanning activities and a pervading

‘cosmopolitanism’ (Greenhalgh et al, 2004; Damschroder et al, 2009). In addition to this, informants

perceived the increased use of data and monitoring and the realignment of incentives as positively

promoting collaboration and better outcomes. In terms of financing (ii) the programme very eectively

negated many aspects of the existing siloed payments systems for various aspects of HIV services which

actors felt had stymied attempts for providers to implement evidence-informed practice (for instance

in relation to ED and Primary Care testing), or to adapt to practical realities (such as identifying LTFU

patients and providing more flexibility for not-for-profit provider organisation outreach work).

26

The programme adapted and grew over the three years with new provider organisations recruited

over the lifetime of the programme and new emphases on delivery developed – for example through

the expanded use of GP champions. This adaptability proved to be very beneficial in relation to the

COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020 (see Stanworth, 2022) and presaged a pivot to greater LTFU work.

Community providers welcomed the flexibility that the programme aorded them overall, though issues

were noted by some providers in relation to how SIB-financed work may have been seen to duplicate

existing work commissioned more conventionally. This ‘messiness’ of competing contracts, and

perceptions of ‘double-dipping’ was problematic and caused extra labour for some actors and reflects

the complexity of the existing commissioning landscape with resultant conflicts, and the overall lack of

coordination between NHS and not-for-profit service provisions.

The role of EJAF was praised by informants. The organisation played a key boundary spanning function

and delivered leadership, support, and encouragement to other organisations. EJAF were crucial

players in the design, financing, and delivery of the programme acting as co-commissioners, financial

intermediaries, project managers, and data analysts. EJAF successfully disrupted many of the existing

inter-organisational, financial, and institutional barriers that historically inhibited more systematic

implementation of testing, LTFU and better joined-up HIV service provision. EJAF were instrumental

in shaping an ‘outer context’ conducive to improving HIV services in South London. Namely, EJAF

facilitated the establishment of systematic processes that helped enable other organisations and

individuals to focus on identifying and caring for people living with HIV – free from some of the

organisational and financial impediments that had hindered such work previously.

Rather than one ‘intervention’ the qualitative data highlighted that the actors involved in commissioning

and delivering HIV services through the Zero HIV SIB programme felt they were delivering a suite of

‘interventions’. Some of these have a strong existing evidence base and have been recommended in

existing guidelines whilst others are more organisational and pragmatic. Some were new and developed

as part of the Zero HIV SIB programme whilst others were already in existence in some or other settings.

A key finding was increased flexibility and local discretion to use funds to tailor services more closely to

27

the needs of those using services as we have seen in other health focused SIBs in the UK (Fraser et al,

2018).

A key aim of the programme was to further the evidence for these interventions and change practice

going forward. A criticism of the programme raised by some informants was that more work could have

been done to ‘baseline’ existing practice and prove the attribution of some of these interventions in

order to provide a more robust body of evidence to sustain these going forward once the SIB financing

ended in December 2021. Though beyond the scope of this current service evaluation, it appears that

learning from the programme (particularly in relation to ED testing) may have been used to inform

national and local level policymakers in future HIV policy development.

There are mixed views from informants in relation to the sustainability of the improvements to South

London HIV services delivered through the Zero HIV SIB programme after the SIB-financing is gone. The

regional commissioning ecosystem is undergoing a further reconfiguration as the new Integrated Care

System is developed. More research is needed to follow these developments over the coming years.

One interesting question that divided informants to a degree related to the extent and nature of public

versus third sector financing and delivery of HIV services in the future.

Defining the Zero HIV SIB-financed ‘intervention’

Figure 2 presents a useful graphic representation of the dierent interventions which occurred in

dierent settings and locations as delivered by various NHS and non-NHS provider organisations.

Figure 2: Overview graphic of Zero HIV SIB programme interventions (taken from Stanworth, 2022)

Secondary Care

(Hospitals)

Primary Care Community

• Oer ‘opt-out’ tesing and support to those who access services

• Identify those LTFU when they access services

• Proactively contact those identified LTFU by data analysis

• User HIV experts and champions to support and educate

colleagues in how to engage patients

• Oer testing and support in a

variety of community settings

• Target those most vulnerable

and least likely to seek

treatment

Hospital Trusts GP Foundations VCSEs

Accident and emergency

departments

Other surgical wards

GP surgeries

Hospitality venues

Saunas and gyms

Barbers

Places of worship

Healthcare setting

Interventions

Providers

Locations

In the qualitative interviews we asked participants to define and explain the Zero HIV programme in

their own words – whether as a health ‘intervention’ or something else. Most informants emphasised the

multi-modal and multi-locational nature of ‘intervention’:

28

‘There are dierent programmes running in dierent services, so you’ve got the community

organisations, you’ve got things running in Primary Care through the GPs and then through

Secondary Care in hospitals and HIV clinics. So, for example we have the HIV testing

on new patient registration in GP surgeries for example, or testing patients for HIV who

have never had an HIV test as they’re going for other routine bloods, we’ve got community

organisations who are actively going out and doing point of care testing at events or

amongst particularly aected ethnic groups… And then in the hospitals, we’ve got the

introduction of the routine opt out testing, HIV testing in the A&E department, so anyone

who visits and hasn’t ever had an HIV test or not had one in the last twelve months will

have that test added onto their bloods. And then we’ve got the HIV clinics who are setting

up more robust pathways for patient recall and auditing their clinics to nd out who’s not

been seen in the last twelve months and bringing people back into care.’

Hospital nurse 1

This informant went on to highlight the way that the programme combines an experimental element –

i.e., building an evidence base around local eectiveness with a commitment to following established

guidelines:

‘It’s experimental but it’s also, you know, what we’re doing is based on best practice…

that’s outlined by NICE and BHIVA, but the resources have not been sucient for it to

happen. So, I suppose it’s not routine, it hasn’t been routine in the past for HIV testing to

be done in the A&E Departments, but it is clear in NICE guidance that it should be done

in areas of high incidence, which our hospital is in an area of very high incidence of HIV.

And that’s not happening [outside of this programme]. And I think the main reason, well,

in my limited understanding, the main reason it’s not being done is because there’s other

priorities and because there’s not the funding, it’s not been prioritised as a funding, or it’s

not been a priority funding need… there must be a lot of things that are in guidelines and

best practice documents that we all know that’s what we should be doing but actually it’s

not achievable within the budget that we are aorded.’

Hospital nurse 1

For many informants, the programme functioned as a way to encourage greater and more consistent

uptake of existing evidence-informed practices by removing traditional barriers linked to funding,

stang, or competing clinical or organisational priorities. The commissioning manager below

emphasises the ways in which the programme goes beyond initial testing and LTFU work to encompass

greater support post-diagnosis to encourage all patients to enter (or re-enter) NHS care.

‘At its core, it’s HIV testing, and then communication with people who are, identication

and communication with people who have dropped out of care. So, HIV testing, but also,

I guess, what’s slightly dierent with some of the more transactional HIV testing stu

we fund is that, obviously, the outcome paid for is HIV identied and the person enters

care, so people have to take them all the way on that journey. Now, of course, that’s not

the only intervention under the SIB, in the sense that it’s funded more developmental

stu, GP champions, etc., but generally, that’s been about building networks and clinical

infrastructure to support testing across our local, well, what I would say our ICS [Integrated

Care System], but really, it’s Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham.

29

We haven’t expanded it out to Southeast London yet, but [this is an aim]’

NHS/LA service commissioner

Alongside this greater support for people living with HIV, the programme functions at a regional level

to foster the development of increased clinical skills and networked working alongside deeper inter-

organisational collaboration.

For some of those involved these dierent interventions were new – but not for others:

‘Was there anything novel? So, whilst some of this work had been done in some settings

and wasn’t novel at all, had been doing it for some time, any time you brought it to a new

setting it was novel. So, if you were a GP practice that you’ve never done HIV testing

for any of your patients, it’s novel… And again, in the A&E departments where it was

embedded and it wasn’t particularly novel, but telling another A&E department, who

are at out and not meeting their four-hour waits and falling over and got NHS[England]

breathing down their necks, it’s not only novel, it’s almost beyond comprehension that

you’re now asking them to do something else, which they quite oen don’t perceive to be a

high priority.’

Commissioner 4

This informant captures the complexity and variability of the pre-existing situation and how the

programme sought to encourage greater standardisation across the boroughs involved. Interestingly,

the evaluator of the programme – with extensive experience of other SIBs -noted the uniqueness of this

programme compared with other SIBs in relation to the variation in numbers, types and settings in which

‘interventions’ take place.

In summary, informants positively emphasised the multi-dimensional nature of the programme and how

it encouraged a more standardised uptake of various complementary activities that sought to identify

new and existing people living with HIV through clinical and organisational interventions and practices

across a variety of healthcare and community settings. The programme identified existing obstacles

to the implementation and normalisation of evidence-informed practices and proposed solutions to

overcome these in a more systematic way.

30

Secondary Care

We collected data from NHS sta working predominantly in two dierent Southeast London hospital

settings. In this report we mostly aggregate the findings from both settings. In further academic work

we plan to explore the dierences across these two ‘inner settings’ (Damschroder et al, 2009) in more

detail. Hospital sta emphasised two distinct activities or interventions at the secondary care level. The

first of these is ‘opt-out HIV testing’ which took place predominantly in the Emergency Department (ED)

of each hospital with a view to diagnosing new HIV cases. The second is the identification and active

tracing and communication with people with a known existing HIV diagnosis who had disengaged from

NHS HIV clinical services – or colloquially - ‘lost to follow-up’ (LTFU). In practice, there was a good degree

of cross-over between these two activities, notwithstanding this, we explore them separately below.

Opt-out HIV testing in the ED

The Zero HIV programme set out to institute and regularise HIV testing for all patients who required

blood tests on presentation at the ED department in participating hospitals. This initiative was in line

with existing (British HIV Association) BHIVA and NICE guidance. However, prior to the Zero HIV

programme, it had been hard to implement this locally for a number of reasons including (1) financing

(2) sta reluctance and (3) competing organisational priorities.

Financing ED opt-out HIV testing has long been problematic, falling between the cracks of the three

potential funders – Local Authorities (LA), Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCG) and NHS England

(NHSE)– as articulated by a hospital manager:

‘That’s why, historically, when we’ve done what’s called our provider intentions, when we

set out service developments, we’ve always put that we would like ED tests, HIV testing in

ED, to be funded. And Local Authorities have always pushed back because, within their

commissioning arm, what’s been delegated to them from the government is not anything

to do with preventative sexual health. So, they’re not responsible for that funding element,

whereas our CCG commissioners, they’re also not technically funded for any preventative

care for HIV, which involves testing. You’re only tested, for example, if you came into the

hospital, maybe you were in critical care, and they’ve eliminated, maybe, majority of all

the other tests that could be contributing to your illness, they’ll be like, we should test you

for HIV, we’re going to ask you, have you ever had an HIV test? So, it was then in those

instances that a certain number of patients would then be tested. But within our contract

with CCG commissioners or NHS England commissioners, there is no, sort of, requirement

for them to fund for testing for HIV, either in ED or just as routine. So, NHS England fund

our HIV treatment as part of their specialised services arm, so they would actually fund

treatment once you’ve been diagnosed with HIV [but not testing in the rst place].’

NHS manager 1

31

SIB-financing as part of the Zero HIV programme solved this historical problem by explicitly stepping

in and funding HIV opt-out testing in the ED. The funding model that was negotiated between EJAF for

one of the NHS trusts was structured in such a way that it guaranteed a minimum funding level so that

the hospital would not be out of pocket regardless of the ‘success’ of the new testing regime, and also

incentivised them to reach as many people living with HIV as possible. In this way it removed the barrier

of financing which had prevented opt-out testing in ED to take place hitherto. This might be seen as a

SIB-related flexibility mechanism.

The desire to increase testing was there from HIV specialist sta already – but the EJAF funding enabled

them to move from ‘one-os’ to a more regularised model:

‘So as soon as I came here, I started to try and get HIV testing a little bit improved in

other departments. And ED was the obvious one. But hit a lot of brick walls in terms of

nancing. So, I did manage to persuade people to let me do things on World Aids Day and

HIV testing week, and things like that. And they were just one os. And actually, even

back then, still dealing with quite a bit of prejudice and stigma amongst the sta. A lot of

misconceptions that it would take an awful lot of time, and a lot of concerns about consent

process of testing someone for HIV... And so, a lot of education around various dierent

departments and sta and trying to feedback when there were late diagnoses – not always

being greeted with great response to that. And then just felt like I was coming up against

a brick wall the entire time in terms of funding, so when EJAF came along, it was just

brilliant. And to be honest, we just started very, very promptly because we’d already done

all of that kind of groundwork, and actually the main issue was cost.’

HIV Consultant 1

The theme of sta reluctance to engage and HIV stigma in the quote above was a recurring one noted by

HIV champions – replicated by a nurse below:

‘Throughout my nursing career I’ve always had an interest in HIV. So, where I trained…

it’s a very taboo subject... So, we had a patient in ED at [another London hospital] that

had come in aer a chemsex party, really unwell, and it was just the nurse’s attitude. I

overheard them talking about HIV and it was just the nurse’s attitude, and I was like

“Actually we need to change this”. So, this is why I am now quite passionate about it. So,

my involvement in the ED down in [this hospital] was actually I liaised with, so my link

role as an emergency nurse practitioner was sexual health, so I was liaising with the [HIV]

Clinic and bits and pieces, trying to push it. And from my own experiences, good health

promotion experience as well. The one thing I was quite keen about is actually we need to

get people talking about it and making it an everyday norm and I think that’s why I like it

because actually it’s, the management of HIV has come such a long way and we now treat

it as a, what I would call a chronic condition because of medication, so actually let’s get it

out into the forefront and talk about it and make it an everyday conversation, not a taboo

conversation.’

Hospital nurse 2

32

A strong and consistent finding was the level of personal and professional dedication that the vast

majority of informants had towards people living with HIV and career-long desire to improve HIV services

– however, these commitments from HIV champions were sometimes not taken-up by non-HIV specialist

clinical sta. This is important because the majority of work actually done to deliver opt-out testing was

not carried out by HIV specialist clinicians – but ED nurses. Therefore, a significant implementation

challenge revolved around changing the perceptions, attitudes and working practices of ED nursing sta.

This involved changing the culture and dialogue from asking ‘do you want an HIV test’ to ‘this is an area

of HIV incidence. We test everyone unless you ask us not to’.

Non-specialist HIV nursing sta reported how in the years prior to the Zero HIV programme, opt-out

testing in ED had not been the norm – indeed HIV testing in ED was rare and only tended to occur when

ordered by doctors if clinically relevant. With the introduction of the Zero HIV programme, a programme

of awareness raising had taken place:

‘During handover [Band 7 nurses] will just tell us “OK we’re doing the HIV testing for

all patients. You just have to tell [the patients], ask for permission and that’s it. If they

don’t want, then just not do it” – something like that. It was very quick, really simple. To

be honest not a lot of us were complying to it at the very rst I think weeks, or probably

months, and even now some of us do not do it.’

Hospital nurse 3

The new opt-out testing initiative adds further complexity to the interactions that nurses must have with

patients thereby increasing the time it takes to triage patients. It also emerged that some spaces are

more conducive to these conversations than others:

‘It’s also a very dicult conversation, and they have brought this up, because it’s OK if it’s

triage because you are in a room, in a private room and it’s you and the patient. But it’s

quite dierent say for instance if you were in Majors. When we get a lot of patients, and we

33

don’t have enough cubicles we let them sit on the grey chairs and sometimes they sit beside

each other, and those conversations are quite dicult to ask them if they want HIV testing

when other patients or relatives of patients can hear you. So, I brought this to the matron’s

attention that it’s hard to get the patient’s consent, because in my opinion the consent for

HIV screening needs to be private.’

Hospital nurse 3

It is apparent that ED opt-out HIV testing can be challenging in the inner setting of hospital EDs. In

another hospital involved in the Zero HIV programme, the approach taken was dierent, in that notional

consent for testing was assumed – and this was achieved through extensive publicity about HIV testing

– for instance through leaflets and posters.

The key factors in mitigating these challenges were HIV specialist sta linking into and liaising with ED

sta – in particular the Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) role seems crucial:

‘I think there was some resistance from some of the sta in A&E about the testing, but we

learned to work with the people who were really on-board with it and kind of used them as

our channel, but the important thing for me was to try and build a relationship between the

clinic and the sta there, so yeah, I would go to A&E handovers. I did try and go to some

of the doctors’ handovers, which I did a little bit, just at the beginning you really want to

get it into people’s minds. I went to a number of the sta training days for A&E for the sta

nurses and the HCAs, I went and did sessions with the new rotating doctors as well’

Hospital nurse 1

The CNS role is significant in terms of boundary spanning from the HIV-specialist setting to the ED.

Numerous informants spoke of the significance of the regular presence of the CNS during shift handover

and also the feedback in relation to patient outcomes that the CNS provided. This is important as a way

of expanding support for the intervention through highlighting the significance of the intervention and

the value it has for patients and improving care:

‘Eventually I got onto the ED Friday news, so I would start – I would particularly go back

and share case studies – so when we had our rst new diagnosis it couldn’t have been

a better patient case study because it blew people’s minds, that an 85 year old was the

rst lady that was tested… that was so helpful because suddenly people started to go ‘oh

right, OK, this is bigger than the gay community and our drug users’ and, you know, it

really helped, so sharing those case studies, as I went I’d say ‘right we’ve had four new

diagnoses this month’ and share some of the stories and that really helped people to see the

importance of the testing.’

Hospital nurse 1

34

Having the CNS in place and able to aid the opt-out ED HIV testing intervention with support from

HIV specialist colleagues highlights the organisational prioritisation of HIV services linked to the

Zero HIV programme – such prioritisation had previously been lacking. The CNS role was partially

funded by outcomes from the Zero HIV programme. In addition to the clinical champion activities, the

CNS also plays a substantial role in data collection and presentation related to ED diagnoses and has

a clear understanding of the links between new diagnoses and outcomes payments, reiterating the