Understanding

California’s Property Taxes

MAC TAYLOR • LEGISLATIVE ANALYST • NOVEMBER 29, 2012

An LAO RepORt

2 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

CONTENTS

Executive Summary ..................................................................................................5

Introduction ..............................................................................................................7

What Is on the Property Tax Bill? .............................................................................7

How Are Property Taxes and Charges Determined? ..............................................8

What Properties Are Taxed? ...................................................................................14

How Is the Revenue Distributed? ..........................................................................17

Why Do Local Government Property Tax Receipts Vary? ....................................22

Are There Concerns About How Property Taxes Are Distributed? ......................24

What Are the Strengths and Limitations of California’s

Property Tax System? .........................................................................................26

Appendix 1:

The History of California’s Property Tax Allocation System ................................33

Tax Allocation Prior to Proposition13 ..................................................................34

Proposition13 and the State’s Response .............................................................34

Changes to the AB 8 System ..................................................................................37

Limits on the State’s

Authority Over Property Tax Allocation ...............................................................41

Looking Forward ....................................................................................................43

Appendix 2:

Property Tax and Local Government Publications ..............................................44

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 3

An LAO RepORt

4 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

e various taxes and charges on a California property tax bill are complex and oen not well

understood. is report provides an overview of this major source of local government revenue and

highlights key policy issues related to property taxes and charges.

A Property Tax Bill Includes a Variety of Dierent Taxes and Charges. A typical California

property tax bill consists of many taxes and charges including the 1 percent rate, voter-approved debt

rates, parcel taxes, Mello-Roos taxes, and assessments. is report focuses primarily on the

1 percent rate, which is the largest tax on the property tax bill and the only rate that applies uniformly

across every locality. e taxes due from the 1 percent rate and voter-approved debt rates are based on

a property’s assessed value. e California Constitution sets the process for determining a property’s

taxable value. Although there are some exceptions, a property’s assessed value typically is equal to its

purchase price adjusted upward each year by 2 percent. Under the Constitution, other taxes and charges

may not be based on the property’s value.

e Property Tax Is One of the Largest Taxes Californians Pay. In some years, Californians pay

more in property taxes and charges than they do in state personal income taxes, the largest

state General Fund revenue source. Local governments collected about $43 billion in 2010-11 from the

1 percent rate. e other taxes and charges on the property tax bill generated an additional

$12 billion.

e Property Tax Base Is Diverse. Property taxes and charges are imposed on many types of

property. For the 1 percent rate, owner-occupied residential properties represent about

39 percent of the state’s assessed value, followed by investment and vacation residential properties

(34 percent) and commercial properties (28 percent). Certain properties—including property owned by

governments, hospitals, religious institutions, and charitable organizations—are exempt from the

1 percent property tax rate.

All Revenue From Property Taxes Is Allocated to Local Governments. Property tax revenue remains

within the county in which it is collected and is used exclusively by local governments. State laws control

the allocation of property tax revenue from the 1 percent rate to more than 4,000 local governments,

with K-14 districts and counties receiving the largest amounts. e distribution of property tax revenue,

however, varies signicantly by locality.

e Property Tax Has a Signicant Eect on the State Budget. Although the property tax is a local

revenue source, it aects the state budget due to the state’s education nance system—additional property

tax revenue from the 1 percent rate for K-14 districts generally decreases the state’s spending obligation

for education. Over the years, the state has changed the laws regarding property tax allocation many

times in order to reduce its costs for education programs or address other policy interests.

e State’s Current Property Tax Revenue Allocation System Has Many Limitations. e

state’s laws regarding the allocation of property tax revenue from the 1 percent rate have evolved over

time through legislation and voter initiatives. is complex allocation system is not well understood,

transparent, or responsive to modern local needs and preferences. Any changes to the existing system,

however, would be very dicult.

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 5

California’s Property Tax System Has Strengths and Limitations. Economists evaluate taxes

using ve common tax policy criteria—growth, stability, simplicity, neutrality, and equity. e

state’s property tax system exhibits strengths and limitations when measured against these ve

criteria. Since 1979, revenue from the 1 percent rate has exceeded growth in the state’s economy.

Property tax revenue also tends to be less volatile than other tax revenues in California due to the

acquisition value assessment system. (Falling real estate values during the recent recession, however,

caused some areas of the state to experience declines in assessed value and more volatility than

in the past.) Although California’s property tax system provides governments with a stable and

growing revenue source, its laws regarding property assessment can result in dierent treatment

of similar taxpayers. For example, newer property owners oen pay a higher eective tax rate than

people who have owned their homes or businesses for a long time. In addition, the property tax

system may distort business and homeowner decisions regarding relocation or expansion.

An LAO RepORt

6 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

INTRODUCTION

For many California taxpayers, the property

tax bill is one of the largest tax payments they

make each year. For thousands of California local

governments—K-12 schools, community colleges,

cities, counties, and special districts—revenue from

property tax bills represents the foundation of their

budgets.

Although property taxes and charges play a

major role in California nance, many elements

of this nancing system are complex and not well

understood. e purpose of this report is to serve

as an introductory reference to this key funding

source. e report begins by explaining the most

common taxes and charges on the property

tax bill and how these levies are calculated. It

then describes how the funds collected from

property tax bills—$55billion in 2010-11—are

distributed among local governments. Last, because

California’s property taxation system has evoked

controversy over the years, the report provides

a framework for evaluating it. Specically, we

examine California property taxes relative to

the criteria commonly used by economists for

reviewing tax systems, including revenue growth,

stability, simplicity, neutrality, and equity. e

report is followed with an appendix providing

further detail about the allocation of property tax

revenue.

A California property tax bill includes a variety

of dierent taxes and charges. As shown on the

sample property tax bill in Figure1, these levies

commonly include:

• e 1percent rate

established by

Proposition13 (1978).

• Additional tax rates

to pay for local voter-

approved debt.

• Property assessments.

• Mello-Roos taxes.

• Parcel taxes.

e Constitution

establishes a process for

determining a property’s

taxable value for purposes of

calculating tax levies from

the 1percent rate and voter-approved debt. In our

sample property tax bill, “Box A” identies the

taxable value of the property and “Box B” shows

the property’s tax levies that are calculated based

ARTWORK #120521

Property ID: 1234567

Mailing Address:

Doe, Jane

1234 ABC Street

Sacramento, CA 00000

2012-13 Roll

Land

Improvements

Total

Less Exemptions

Net Assessed Value

Assessed Value

$115,000.00

$242,000.00

$357,000.00

$7,000.00

$350,000.00

Secured Property Tax for Fiscal Year July 1, 2012 to June 30, 2013

Property Owner Information

Property Valuation on Jan 1, 2012

Detail of Taxes Due

Sample Annual Property Tax Bill

Agency

General Tax Levy

Voter-Approved Debt Rates

City

Water District

School District

Community College District

Direct Levies

Sidewalk District Assessment

Flood Control District Assessment

Street Lighting District Assessment

Mello-Roos District

School District Parcel Tax

Total Taxes Due

1st Installment

2nd Installment

Rate

1.0000

0.0201

0.0018

0.1010

0.0102

Amount

$3,500.00

$70.35

6.30

353.50

35.70

$9.36

64.39

12.71

86.51

125.00

$4,263.82

$2,131.91

2,131.91

Figure 1

B

C

D

A

Graphic Sign Off

Secretary

Analyst

Director

Deputy

WHAT IS ON THE PROPERTY TAX BILL?

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 7

on this value. Levies based on value—such as the

1percent rate and voter-approved debt rates—are

known as “ad valorem” taxes.

Under the Constitution, other taxes and

charges on the property tax bill (shown in

“Box C”) may not be based on the property’s

taxable value. Instead, they are based on other

factors, such as the benet the property owner

receives from improvements.

As shown in “Box D,” the total amount due on

most property tax bills is divided into two equal

amounts. e rst payment is due by December 10

and the second payment is due by April 10.

HOW ARE PROPERTY TAXES

AND CHARGES DETERMINED?

Ad valorem property taxes—the 1percent rate

and voter-approved debt rates—account for nearly

90percent of the revenue collected from property

tax bills in California. Given their importance,

this section begins with an overview of ad

valorem taxes and describes how county assessors

determine property values. Later in the chapter, we

discuss the taxes and charges that are determined

based on factors other than property value.

Taxes Based on Property Value

e 1Percent Rate. e largest component

of most property owners’ annual property

tax bill is the 1percent rate—oen called the

1percent general tax levy or countywide rate. e

Constitution limits this rate to 1percent of assessed

value. As shown on our sample property tax bill,

the owner of a property assessed at $350,000 owes

$3,500 under the 1percent rate. e 1percent rate

is a general tax, meaning that local governments

may use its revenue for any public purpose.

Voter-Approved Debt Rates. Most tax bills

also include additional ad valorem property tax

rates to pay for voter-approved debt. Revenue

from these taxes is used primarily to repay general

obligation bonds issued for local infrastructure

projects, including the construction and

rehabilitation of school facilities. (As described

in the nearby box, some voter-approved rates are

used to pay obligations approved by local voters

before 1978.) Bond proceeds may not be used for

general local government operating expenses,

such as teacher salaries and administrative costs.

Most local governments must obtain the approval

of two-thirds of their local voters in order to

issue general obligation bonds repaid with debt

rates. General obligation bonds for school and

community college facilities, however, may be

approved by 55percent of the school or community

college district’s voters. Local voters do not

approve a xed tax rate for general obligation bond

indebtedness. Instead, the rate adjusts annually so

that it raises the amount of money needed to pay

the bond costs.

Property tax bills oen include more than one

voter-approved debt rate. In our sample property

tax bill, for example, the property owner is subject

to four additional rates because local voters have

approved bond funds for the city and water,

school, and community college districts where the

property is located. ese rates tend to be a small

percentage of assessed value. Statewide, the average

property tax bill includes voter-approved debt rates

that total about one-tenth of 1percent of assessed

value.

An LAO RepORt

8 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

Calculating Property Value for

Ad Valorem Taxes

One of the rst items listed on a property

tax bill is the assessed value of the land and

improvements. Assessed value is the taxable value

of the property, which includes the land and any

improvements made to the land, such as buildings,

landscaping, or other developments. e assessed

value of land and improvements is important

because the 1percent rate and voter-approved

debt rates are levied as a percentage of this value,

meaning that properties with higher assessed

values owe higher property taxes.

Debt Approved by Voters Prior to 1978

e California Constitution allows local governments to levy voter-approved debt

rates—ad valorem rates above the 1percent rate—for two purposes. e rst purpose is to

pay for indebtedness approved by voters prior to 1978, as allowed under Proposition13 (1978).

Proposition42 (1986) authorized a second purpose by allowing local governments to levy additional

ad valorem rates to pay the annual cost of general obligation bonds approved by voters for local

infrastructure projects. Because most debt approved before 1978 has been paid o, most voter-

approved debt rates today are used to repay general obligation bonds issued aer 1986 as authorized

under Proposition42.

Some local governments, however, continue to levy voter-approved debt rates for indebtedness

approved by voters before 1978. While most bonds issued before the passage of Proposition13 have

been paid o, state courts have determined that other obligations approved by voters before 1978

also can be paid with an additional ad valorem rate. Two common pre-1978 obligations paid with

voter-approved debt rates are local government employee retirement costs and payments to the State

Water Project.

Voter-Approved Retirement Benets. Voters in some counties and cities approved ballot

measures or city charters prior to 1978 that established retirement benets for local government

employees. e California Supreme Court ruled that such pension obligations represent voter-

approved indebtedness that could be paid with an additional ad valorem rate. Local governments

may levy the rate to cover pension benets for any employee, including those hired aer 1978, but

not to cover any enhancements to pension benets enacted aer 1978. Local governments may adjust

the rate annually to cover employee retirement costs, but state law limits the rate to the level charged

for such purposes in 1982-83 or 1983-84, whichever is higher. A recent review shows that at least

20 cities and 1 county levy voter-approved debt rates to pay some portion of their annual pension

costs. e rates dier by locality. For example, the City of Fresno’s voter-approved debt rate for

employee retirement costs is 0.03percent of assessed value in 2012-13, while the City of San

Fernando’s rate is 0.28percent.

State Water Project Payments. Local water agencies can levy ad valorem rates above the

1percent rate to pay their annual obligations for water deliveries from the State Water Project.

State courts concluded that such costs were voter-approved debt because voters approved the

construction, operation, and maintenance of the State Water Project in 1960. As a result, most water

agencies that have contracts with the State Water Project levy a voter-approved debt rate.

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 9

Under California’s tax system, the assessed

value of most property is based on its purchase

price. Below, we describe the process county

assessors use to determine the value of local “real

property” (land, buildings, and other permanent

structures). is is followed by an explanation of

how assessors determine the value of “personal

property” (property not axed to land or

structures, such as computers, boats, airplanes, and

business equipment) and “state assessed property”

(certain business properties that cross county

boundaries).

Local Real Property Is Assessed at Acquisition

Value and Adjusted Upward Each Year. e

process that county assessors use to determine

the value of real property was established by

Proposition13. Under this system, when real

property is purchased, the county assessor assigns

it an assessed value that is equal to its purchase

price, or “acquisition value.” Each year thereaer,

the property’s assessed value increases by 2percent

or the rate of ination, whichever is lower. is

process continues until the property is sold, at

which point the county assessor again assigns it

an assessed value equal to its most recent purchase

price. In other words, a property’s assessed value

resets to market value (what a willing buyer would

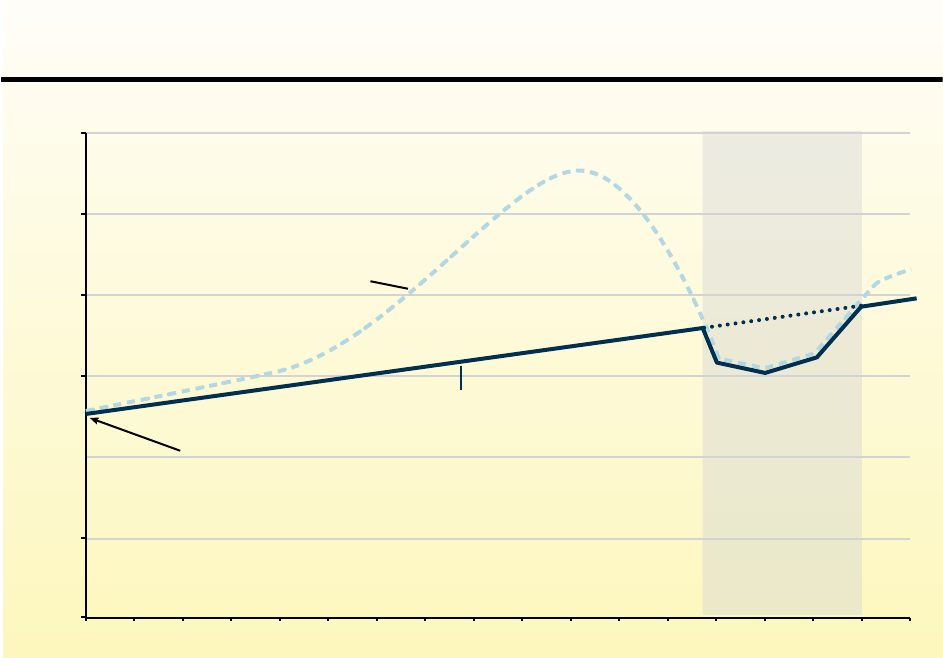

pay for it) when it is sold. (As shown in Figure2,

voters have approved various constitutional

amendments that exclude certain property

transfers from triggering this reassessment.)

In most years, under this assessment practice, a

property’s market value is greater than its assessed

value. is occurs because assessed values increase

by a maximum of 2percent per year, whereas

market values tend to increase more rapidly.

erefore, as long as a property does not change

ownership, its assessed value increases predictably

from one year to the next and is unaected by

higher annual increases in market value. For

example, Figure3 shows how a hypothetical

property purchased in 1995 for $185,000 would

Figure 2

Property Transfers That Do Not Trigger Reassessment

Proposition Year Description

3 1982 Allows property owners whose property has been taken by eminent domain proceedings

to transfer their existing assessed value to a new property of similar size and function.

50 1986 Allows property owners whose property has been damaged or destroyed in a natural

disaster to transfer their existing assessed value to a comparable replacement

property within the same county.

58 1986 Excludes property transfers between spouses or between parents and children from

triggering reassessment.

60 1986 Allows homeowners over the age of 55 to transfer their existing assessed value to a new

home, of equal or lesser market value, within the same county.

90 1988 Extends Proposition 60 by allowing homeowners to transfer their existing assessed value

to a new home, of equal or lesser market value, in a different participating county.

110 1990 Allows disabled homeowners to transfer their existing assessed value from an existing

home to a newly purchased home of equal or lesser market value.

171 1993 Extends Proposition 50 by allowing property owners affected by a natural disaster to

transfer their existing assessed value to a comparable replacement property in a

different participating county.

193 1996 Excludes property transfers between grandparents and grandchildren (when the parents

are deceased) from triggering reassessment.

1 1998 Allows property owners whose property is made unusable by an environmental problem

to transfer their existing assessed value to a comparable replacement property.

An LAO RepORt

10 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

be assessed in 2012. Although the market value

of the property increased to $300,000 by 2002,

the assessed value was $200,000 because assessed

value grew by only up to 2percent each year. Upon

being sold in 2002, the property’s assessed value

reset to a market value of $300,000. Because of the

large annual increase in home values aer 2002,

however, the market value was soon much greater

than the assessed value for the new owner as well.

Property Improvements Are Assessed

Separately. When property owners undertake

property improvements,

such as additions,

remodeling, or building

expansions, the additions

or upgrades are assessed

at market value in that

year and increase by up

to 2percent each year

thereaer. e unimproved

portion of the property

continues to be assessed

based on its original

acquisition value. For example, if a homeowner

purchased a home in 2002 and then added a garage

in 2010, the home and garage would be assessed

separately. e original property would be assessed

at its 2002 acquisition value adjusted upward each

year while the garage would be assessed at its 2010

market value adjusted upward. e property’s

assessed value would be the combined value of the

two portions. (As shown in Figure4, voters have

excluded certain property improvements from

increasing the assessed value of a property.)

Market Value Can Exceed Assessed Value

Figure 3

ARTWORK #120521

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

$600,000

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

Property Purchased in 1995

Assessed at acquisition value.

Assessed Value

Increases by up to

2 percent each year.

Property Sold in 2002

Reassessed to acquisition value, then

increases by up to 2 percent annually.

Market Value

Increases or decreases based

on local real estate conditions.

1996 1998 2000 2002 20122004 2006 2008 2010

Graphic Sign Off

Secretary

Analyst

Director

Deputy

Figure 4

Property Improvements That Do Not Increase a

Property’s Assessed Value

Constitutional Amendments Approved After June 1978

Proposition Year Type of Improvement

8 1978 Reconstruction following natural disaster

7 1980 Solar energy construction

31 1984 Fire-safety improvements

110 1990 Accessibility construction for disabled homeowners

177 1994 Accessibility construction for any property

1 1998 Reconstruction following environmental contamination

13 2010 Seismic safety improvements

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 11

Assessed Value May Be Reduced When Market

Values Fall Signicantly. When real estate values

decline or property damage occurs, a property’s

market value may fall below its assessed value as set

by Proposition 13. Absent any adjustment to this

assessed value, the property would be taxed at a

greater value than it is worth.

In these events, county assessors may

automatically reduce the Proposition 13 assessed

value of a property to its current market value.

If they do not, however, a property owner may

petition the assessor to have his or her assessed

value reduced. ese decline-in-value properties are

oen called “Prop 8 properties” aer Proposition 8

(1978), which authorizes this assessment reduction

to market value. Figure 5 illustrates the assessment

of a hypothetical decline-in-value property over

time. e market value of the property purchased

in 1995 stays above its Proposition 13 assessed

value through 2007. A signicant decline, however,

drops the property’s market value below its

Proposition 13 assessed value. At this time, the

property receives a decline-in-value assessment

(equal to its market value) that is less than its

Proposition 13 assessment. For three years, the

property is assessed at market value, which may

increase or decrease by any amount. By 2012,

the property’s market value once again exceeds

what its assessed value would have been absent

Proposition 8 (acquisition price plus the 2 percent

maximum annual increase). In subsequent years,

the property’s assessed value is determined by its

acquisition price adjusted upward each year.

Homeowners Are Eligible for a Property

Tax Exemption. Homeowners may claim a $7,000

exemption from the assessed value of their primary

residence each year. As shown in “Box A” of the

sample property tax bill in Figure 1, this exemption

lowers the assessed value of the homeowner’s land and

improvements by $7,000, reducing taxes under the

ARTWORK #120521

Assessed Value Can Fall Below Proposition 13 Value

Figure 5

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

$350,000

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Market Value

Increases or decreases based

on local real estate conditions.

Property Purchased

Assessed at acquisition value.

Property Assessed

at Market Value

Proposition 13 Value

Increases by a maximum

of 2 percent each year.

Graphic Sign Off

Secretary

Analyst

Director

Deputy

An LAO RepORt

12 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

1percent rate by $70 and reducing taxes from voter-

approved debt rates by a statewide average of $8.

Two Types of Property Are Assessed at eir

Market Value. Two categories of property are

assessed at their current market value, rather than

their acquisition value: personal property and state-

assessed property. (We provide more information

about these properties in the nearby box.)

Combined, these types of properties accounted for

6percent of statewide-assessed value in 2011-12.

Most personal property and state-assessed property

is taxed at the 1percent rate plus any additional

rates for voter-approved debt.

Determining Other Taxes and Charges

All other taxes and charges on the property

tax bill are calculated based on factors other than

the property’s assessed value. For example, some

levies are based on the cost of a service provided

to the property. Others are based on the size of

a parcel, its square footage, number of rooms, or

other characteristics. Below, we discuss three of

the most common categories of non-ad valorem

levies: assessments, parcel taxes, and Mello-Roos

taxes. In addition to these three categories, some

local governments collect certain fees for service

on property tax bills, such as charges to clear weeds

on properties where the weeds present a re safety

hazard. ese fees are diverse and relatively minor,

and therefore are not examined in this report.

Assessments. Local governments levy

assessments in order to fund improvements that

benet real property. For example, with the approval

of aected property owners, a city or county may

create a street lighting assessment district to fund

the construction, operation, and maintenance of

street lighting in an area. Under Proposition218

(1996), improvements funded with assessments must

provide a direct benet to the property owner. An

assessment typically cannot be levied for facilities

or services that provide general public benets,

such as schools, libraries, and public safety, even

Properties Assessed at Current Market Value

Personal Property. Personal property is property other than land, buildings, and other

permanent structures, which are commonly referred to as “real property.” Most personal property

is exempt from property taxation, including business inventories, materials used to manufacture

products, household furniture and goods, personal items, and intangible property like gym

memberships and life insurance policies. Some personal property, however, is subject to the property

tax. ese properties consist mainly of manufacturing equipment, business computers, planes,

commercial boats, and oce furniture. When determining the market value of personal property,

county assessors take into account the loss in value due to the age and condition of personal

property—a concept known as depreciation. Unlike property taxes on real property, which are due

in two separate payments, taxes on personal property are due on July 3.

State-Assessed Property. e State Board of Equalization is responsible for assessing certain

real properties that cross county boundaries, such as pipelines, railroad tracks and cars, and canals.

State-assessed properties are assessed at market value and, with the exception of railroad cars, taxed

at the 1percent rate plus any additional rates for voter-approved debt. (As part of a federal court

settlement decades ago, railroad cars are taxed at a rate that is somewhat lower than 1percent. e

railcar tax rate varies each year and currently is about 0.8percent.)

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 13

though these programs may increase the value of

property. Moreover, the amount each property

owner pays must reect the cost incurred by the

local government to provide the improvement and

the benet the property receives from it. To impose a

new assessment, a local government must secure the

approval of a weighted majority of aected property

owners, with each property owner’s vote weighted

in proportion to the amount of the assessment he or

she would pay.

Parcel Taxes. With the approval of two-thirds

of voters, local governments may impose a tax

on all parcels in their jurisdiction (or a subset of

parcels in their jurisdiction). Local governments

typically set parcel taxes at xed amounts per

parcel (or xed amounts per room or per square

foot of the parcel). Unlike assessments, parcel tax

revenue may be used to fund a variety of local

government services, even if the service does not

benet the property directly. For example, school

districts may use parcel tax revenue to pay teacher

salaries or administrative costs. e use of parcel

tax revenue, however, is restricted to the public

programs, services, or projects that voters approved

when enacting the parcel tax.

Mello-Roos Taxes. Mello-Roos taxes are a

exible revenue source for local governments

because they (1) may be used to fund infrastructure

projects or certain services; (2) may be levied

in proportion to the benet a property receives,

equally on all parcels, by square footage, or by other

factors; and (3) are collected within a geographical

area drawn by local ocials.

Local governments oen use Mello-Roos

taxes to pay for the public services and facilities

associated with residential and commercial

development. is occurs because landowners

may approve Mello-Roos taxes by a special

two-thirds vote—each owner receiving one vote

per acre owned—when fewer than 12 registered

voters reside in the proposed district. In this way,

a developer who owns a large tract of land could

vote to designate it as a Mello-Roos district. Aer

the land is developed and sold to residential and

commercial property owners, the new owners pay

the Mello-Roos tax that funds schools, libraries,

police and re stations, or other public facilities and

services in the new community. Mello-Roos taxes

are subject to two-thirds voter approval when there

are 12 or more voters in the proposed district.

WHAT PROPERTIES ARE TAXED?

Property taxes and charges are imposed on

many types of properties. ese properties include

common types such as owner-occupied homes and

commercial oce space, as well as less common

types like timeshares and boating docks. In the

section below, we describe the state’s property tax

base—the types of real properties that are subject

to the 1 percent rate and the share of total assessed

value that each property type represents.

Due to data limitations, we do not summarize

the tax bases of other taxes and charges. We note,

however, that the property tax base for other taxes

and charges is dierent from the tax base for the

1 percent rate. is is because the 1 percent rate

applies uniformly to all taxable real property,

whereas other taxes and charges are levied at

various levels and on various types of property

throughout the state (according to local voter or

local government preferences). For example, if

a suburban school district levies a parcel tax on

each parcel in a residential area, the owners of

single-family homes would pay a large share of the

total parcel taxes. Accordingly, the school district’s

parcel tax base would be more heavily residential

An LAO RepORt

14 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

than the statewide property tax base under the

1 percent rate (which applies to all taxable

property).

What Properties Are

Subject to the 1 Percent Rate?

Although most real property is taxable,

the Constitution exempts certain types of real

property from taxation. In general, these are

government properties or properties that are used

for non-commercial purposes, including hospitals,

religious properties, charities, and nonprot

schools and colleges. California properties that

are subject to the property tax, however, can be

classied in three ways:

• Owner-occupied residential—properties

that receive the state’s homeowner’s

exemption, which homeowners may claim

on their primary residence.

• Investment and vacation residential—

residential properties other than those

used as a primary

residence,

including

multifamily

apartments, rental

condominiums,

rental homes,

vacant residential

land, and vacation

homes.

• Commercial—

retail properties,

industrial plants,

farms, and other

income-producing

properties.

Distribution of the

Tax Base for the 1Percent Rate

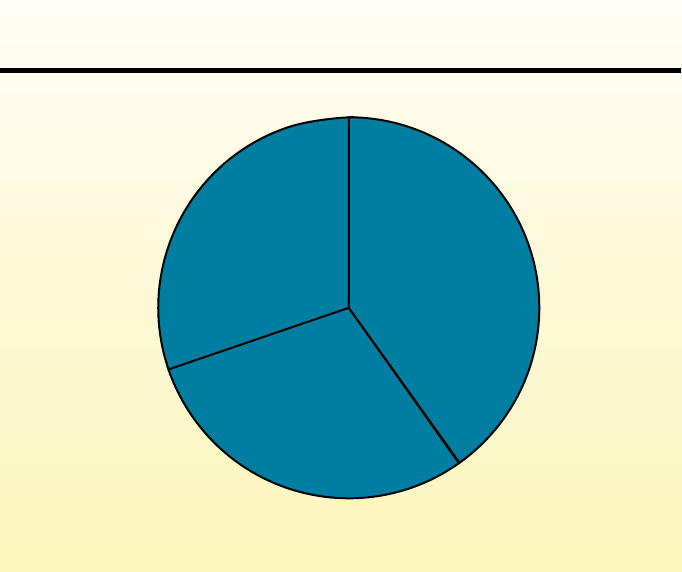

Owner-Occupied Residential. In 2010-11,

there were 5.5million owner-occupied homes

in California with a total assessed value of

$1.6trillion. As shown in Figure6, owner-occupied

residential properties accounted for the largest

share—39percent—of the state’s tax base for the

1percent rate.

Investment and Vacation Residential.

Although the majority of residential properties

are owner occupied, many others are investment

or vacation properties such as multifamily

apartments, rental condominiums, rental homes,

vacant residential land, and vacation homes.

(We classify vacant residential land and vacation

homes as investment properties because they are

an investment asset for the owner, even if he or

she does not receive current income from them.)

In 2010-11, there were 4.2million investment and

vacation residential properties. e assessed value

Share of Assessed Value for Properties Subject to the 1 Percent Rate

a

, 2010-11

a

Excludes personal property and state-assessed property.

Commercial

Owner-Occupied

Residential

Investment and

Vacation Residential

The Distribution of California’s Property Tax Base

ARTWORK #120521

Figure 6

Graphic Sign Off

Secretary

Analyst

Director

Deputy

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 15

of these properties was about $1.4trillion, which

represents 34percent of the state’s total assessed

value.

Commercial. In 2010-11, there were

approximately 1.3million commercial properties

in California. is amount includes about

600,000 retail, industrial, and oce properties

(such as stores, gas stations, manufacturing

facilities, and oce buildings). It also includes

500,000 agricultural properties and 200,000 other

properties (gas, oil, and mineral properties and

the private use of public land). While commercial

properties represent a relatively small share of the

state’s total properties, they tend to have higher

assessed values than other properties. erefore,

as shown in Figure6, these properties (which have

a total assessed value of $1.2 trillion) account for

28percent of the state’s property tax base.

Has the Distribution of the

Property Tax Base Changed Over Time?

ere is little statewide information regarding

the composition of California’s property tax base

over time. Based on the available information,

however, it appears that homeowners may be paying

a larger percentage of total property taxes today

than they did decades ago. We note, for example,

that the assessed value of owner-occupied homes

has increased from a low of 32 percent of statewide

assessed valuation in 1986-87 to a high of

39 percent in 2005-06. (e share was 36 percent

in 2011-12.) It also appears likely that owners of

commercial property are paying a smaller percentage

of property taxes than they did decades ago. For

example, Los Angeles County reports that the share

of total assessed value represented by commercial

property in the county declined from 40 percent in

1985 to 30 percent in 2012. In addition, the assessed

value of commercial property in Santa Clara County

has declined (as a share of the county total) from

29 percent to 24 percent since 1999-00.

What Factors May Have Contributed to

Changes in the Property Tax Base?

Various economic changes that have taken

place over time probably have contributed to

changes to California’s property tax base. For

example, investment in residential property has

increased signicantly since the mid-1970s. Newly

built single-family homes have become larger and

are more likely to have valuable amenities than

homes built earlier. As a result, new homes are

more expensive to build and assessed at higher

amounts than older homes. Over the same period,

commercial activity in California has shied away

from traditional manufacturing, which tends to

rely heavily on real property. Newer businesses, on

the other hand, are more likely to be technology

and information services based. ese businesses

tend to own less real property than traditional

manufacturing rms do. (Technology and

information services rms, however, rely heavily

on business personal property—for example,

computing systems, design studios, and oce

equipment—that are taxed as personal property

and not included in the distribution of the state’s

real property tax base.)

It also is possible that Proposition 13’s

acquisition value assessment system has played

a role in the changes to California’s tax base.

Specically, under Proposition 13, properties

that change ownership more frequently tend to

be assessed more closely to market value than

properties that turn over less frequently. (Because

properties are assessed to market value when

they change ownership, properties that have not

changed ownership in many years tend to have

larger gaps between their assessed values and

market values.) It is possible that some categories of

properties change ownership more frequently than

others and this could inuence the composition

of the overall tax base. e limited available

research suggests that investment and vacation

An LAO RepORt

16 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

residential properties

change ownership

more frequently than

commercial or owner-

occupied residential

property, indicating that

they may be assessed

closer to market value

than other types of

property.

How MucH

Revenue Is

collected?

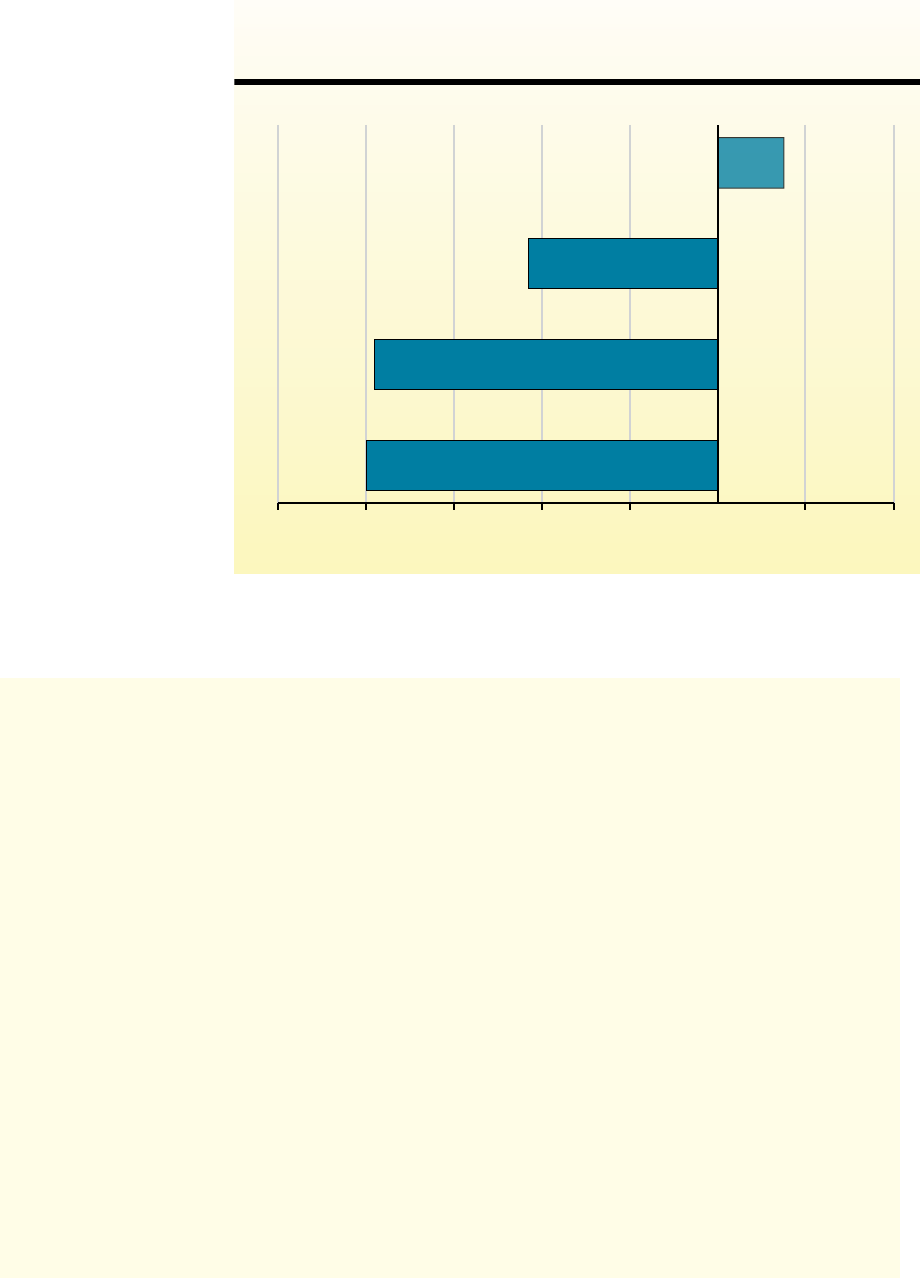

In 2010-11, California

property tax bills totaled

$55 billion. As shown

in Figure7, this amount

included $43.2billion

under the 1percent

rate and $5.7billion from voter-approved debt

rates, making ad valorem property taxes one of

California’s largest revenue sources.

Comparatively little is known about the

remaining $6billion of other taxes and charges

on the property tax bill. From various reports

summarizing local government nances, elections,

and bond issuances, it appears that most of this

$6billion reects property assessments, parcel

taxes, and Mello-Roos taxes, though statewide data

are not available on the exact amounts collected for

each of these funding sources.

2010-11 (In Billions)

Property Tax Revenue Compared

With Other Major Revenue Sources

ARTWORK #120521

Figure 7

1 Percent Rate

Voter-Approved

Debt Rates

Other Taxes

and Charges

10

20

30

40

50

$60

Corporation Tax State and Local

Sales and Use Tax

Personal

Income Tax

Property Taxes

and Charges

Graphic Sign Off

Secretary

Analyst

Director

Deputy

HOW IS THE REVENUE DISTRIBUTED?

California property owners pay their property

tax bills to their county tax collector (sometimes

called the county treasurer-tax collector). e

funds are then transferred to the county auditor

for distribution. e county auditor distributes the

funds collected from the 1percent rate dierently

than the funds collected from the other taxes

and charges on the bill. Specically, the 1percent

rate is a shared revenue source for multiple local

governments.

is section describes the distribution of

revenue raised under the 1percent rate and

summarizes the limited available information

regarding the distribution of voter-approved debt

rates and non-ad valorem property taxes and

charges.

Revenue From the 1Percent Rate Is

Shared by Many Local Governments

e 1percent rate generates most of the

revenue from the property tax bill—roughly

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 17

$43billion in 2010-11. On a typical property

tax bill, however, the 1percent rate is listed as

the general tax levy or countywide rate with no

indication as to which local governments receive

the revenue or for what purpose the funds are used.

In general, county auditors allocate revenue from

the 1percent rate to a variety of local governments

within the county pursuant to a series of complex

state statutes.

More an 4,000 Local Governments Receive

Revenue From the 1Percent Rate. All property

tax revenue remains within the county in which

it is collected to be used exclusively by local

governments. As shown in Figure8, property tax

revenue from the 1percent rate is distributed to

counties, cities, K-12 schools, community college

districts, and special districts. Until recently,

redevelopment agencies also received property

tax revenue. As described in the nearby box,

redevelopment agencies were dissolved in 2012, but

a large amount of property tax revenue continues

to be used to pay the former agencies’ debts and

obligations.

Figure 9 shows the share of revenue received by

each type of local government from the 1 percent

rate and voter-approved debt rates. (As described

later in the report, however, these shares vary

signicantly by locality.)

Property Taxes Also Aect the State Budget.

Although the state does not receive any property

tax revenue directly, the state has a substantial

scal interest in the distribution of property

tax revenue from the 1percent rate because of

the state’s education nance system. Each K-12

district receives “revenue limit” funding—the

largest source of funding for districts—from the

combination of local property tax revenue under

the 1percent rate and state resources. us, if

a K-12 district’s local property tax revenue is

not sucient to meet its revenue limit, the state

provides additional funds. Community colleges

have a similar nancing system, in which each

district receives apportionment funding from

local property tax revenue, student fees, and state

resources. In 2010-11, the state contributed

$22.5 billion to K-12 revenue limits and community

college apportionments, while the remainder

($14.5 billion) came from local property tax

revenue (and student fees).

State Laws Direct Allocation of Revenue

From the 1Percent Rate. e county auditor is

responsible for allocating revenue generated from

the 1percent rate to local governments pursuant

to state law. e allocation system is commonly

referred to as “AB 8,” aer the bill that rst

Figure 8

How Many Local Governments Receive

Revenue From the 1 Percent Rate?

Type of Local Government Number

Counties

58

Cities

480

Schools and Community Colleges

K-12 school districts 966

County Offices of Education 56

Community college districts 72

Special Districts

Fire protection 348

County service area 316

Cemetery 241

Community services 201

Maintenance 136

Highway lighting 117

County water 100

Recreation and park 85

Hospital 64

Sanitary 60

Irrigation 46

Mosquito abatement 43

Public utility 43

Other

a

400

Redevelopment Agencies

b

422

Total 4,254

a

Thirty three other types of special districts report receiving

property tax revenue from the 1 percent rate. These include county

sanitation, municipal water, memorial, water authority, drainage,

and library districts.

b

Dissolved in 2012. A portion of property tax revenue continues to

pay these agencies’ debts and obligations.

An LAO RepORt

18 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

implemented the system—

Chapter282, Statutes of

1979 (AB 8, L. Greene).

In general, AB 8 provides

a share of the total

property taxes collected

within a community to

each local government

that provides services

within that community.

Each local government’s

share is based on its

proportionate countywide

share of property taxes

during the mid-1970s,

a time when each local

government determined

its own property tax rate

and property owners paid

taxes based on the sum of

Most Ad Valorem Property Tax Revenue

Is Allocated to Schools and Counties

a

Figure 9

ARTWORK #120521

2010-11

a

As a percentage of total revenue from the 1 percent rate and voter-approved debt rates.

b

Redevelopment agencies were dissolved in 2012. Successor agencies will continue to use property

tax revenue to pay former agencies' debts and obligations.

K-14 Districts

Counties

Cities

Redevelopment

Agencies

b

Special

Districts

Graphic Sign Off

Secretary

Analyst

Director

Deputy

Redevelopment and Successor Agencies

More than 60 years ago, the Legislature established a process whereby a city or county could

declare an area to be blighted and in need of redevelopment. Aer this declaration, most property

tax revenue growth from the redevelopment “project area” was distributed to the redevelopment

agency, instead of the other local governments serving the project area. As discussed in our report,

e 2012-13 Budget: Unwinding Redevelopment, redevelopment agencies were dissolved in February

2012. Prior to their dissolution, however, redevelopment agencies received over $5billion in property

tax revenue annually. ese monies were used to pay o tens of billions of dollars of outstanding

bonds, contracts, and loans.

In most cases, the city or county that created the redevelopment agency is managing its

dissolution as its successor agency. e successor agency manages redevelopment projects currently

underway, pays existing debts and obligations, and disposes of redevelopment assets and properties.

e successor agency is funded from the property tax revenue that previously would have been

distributed to the redevelopment agency. As a result, even though redevelopment agencies have

been dissolved, some property tax revenue continues to be used to pay redevelopment’s debts and

obligations. Over time, most redevelopment obligations will be retired and the property tax revenue

currently distributed to successor agencies will be distributed to K-14 districts, counties, cities, and

special districts.

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 19

these rates. (e average property tax rate totaled

about 2.7 percent.) As a result, local governments

that received a large share of property taxes in the

1970s typically receive a relatively large share of

revenue from the 1percent rate under AB 8. (More

detail on the history of the state’s property tax

allocation system—including AB 8—is provided in

the appendix of this report.)

Revenue Allocated by Tax Rate Area

(TRA). e county auditor allocates the revenue

to local governments by TRA. A TRA is a

small geographical area within the county that

contains properties that are all served by a unique

combination of local governments—the county, a

city, and the same set of special districts and school

districts. A single county may have thousands of

TRAs. While there is considerable variation in

the steps county auditors use to allocate revenue

within each TRA, typically the county auditor

annually determines how much revenue was

collected in each TRA and rst allocates to each

local government in the TRA the same amount

of revenue it received in the prior year. Each local

government then receives a share of any growth

(or loss) in revenue that occurred within the TRA

that year. Each TRA has a set of growth factors that

specify the proportion of revenue growth that goes

to each local government. ese factors—developed

by county auditors pursuant to AB 8—are

largely based on the share of revenue each local

government received from the TRA during the late

1970s.

Figure10 shows sample growth factors for

TRAs in two California cities. As the gure

indicates, 23percent of any growth in revenue from

the 1percent rate in the sample TRA for Norwalk

would be allocated to the county, 7percent would

go to the city, and the rest would be allocated to

various educational entities and special districts.

e percentage of property tax growth allocated

to each type of local government can vary

signicantly by TRA. For example, Walnut Creek’s

K-12 school district receives 33percent of the

growth in revenue within its TRA while Norwalk’s

school district receives only 19percent from its

TRA. As noted above, this variation is based largely

on historical factors specied in AB 8.

Some Revenue Is Allocated to a Countywide

Account—ERAF. Most of the revenue from the

1percent rate collected within a TRA is allocated

to the city, county, K-14 districts, and special

districts that serve the properties in that TRA. State

law, however, directs the county auditor to shi a

portion of this revenue to a countywide account

that is distributed to other local governments

that do not necessarily serve the taxed properties.

e state originally established this account—the

Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund

(ERAF)—to provide additional funds to K-14

districts that do not receive sucient property tax

revenue to meet their minimum funding level. State

laws later expanded the use of ERAF to include

reimbursing cities and counties for the loss of

other local revenue sources (the vehicle license fee

and sales tax) due to changes in state policy. For

example, Figure 10 shows that 20percent of any

revenue growth within Norwalk’s TRA is deposited

into ERAF. It is possible that some or all of this

revenue could be allocated to a city or K-14 district

in a dierent part of Los Angeles County.

Most Revenue From Voter-Approved

Debt Distributed to Schools

Voter-approved debt rates are levied on

property owners so that local governments can

pay the debt service on voter-approved general

obligation bonds (and pre-1978 voter-approved

obligations). e state’s K-12 school districts receive

the majority of the revenue from voter-approved

debt rates ($3.1billion of $5.2billion in 2009-10).

e amount received by cities ($520million),

special districts ($470million), and counties

An LAO RepORt

20 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

Figure 10

Allocation of Property Tax Growth in Sample Tax Rate Areas

Norwalk, Los Angeles County

a

Percent

Share

Los Angeles County 23%

Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund 20

Norwalk-La Mirada Unified School District 19

Los Angeles County Fire Protection District 18

City of Norwalk 7

Norwalk Parks and Recreation District 3

Los Angeles County Library 2

La Mirada Parks and Recreation District 2

Cerritos Community College District 2

Los Angeles County Flood Control District 1

Los Angeles County Sanitation District 1

Greater Los Angeles County Vector Control —

b

Water Replenishment District of Southern California —

b

Little Lake Cemetery District —

b

Los Angeles County Department of Education —

b

100%

Walnut Creek, Contra Costa County

c

Percent

Share

Mount Diablo Unified School District 33%

Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund 17

Contra Costa County 13

Contra Costa County Fire 13

City of Walnut Creek 9

Contra Costa Community College District 5

East Bay Regional Park District 3

Contra Costa County Library 2

Central Contra Costa Sanitary District 2

Contra Costa County Office of Education 1

Contra Costa County Flood Control 1

Bay Area Rapid Transit 1

Contra Costa Water District 1

Contra Costa County Water Agency —

b

Contra Costa County Resource Conservation District —

b

Contra Costa County Mosquito Abatement District —

b

Contra Costa County Service Area R-8 —

b

Bay Area Air Management District —

b

100%

a

Percentages indicate allocation of the growth in property taxes in Los Angeles County tax rate area 06764.

b

Less than 0.5 percent.

c

Percentages indicate allocation of the growth in property taxes in Contra Costa County tax rate area 09025.

($320million) is signicantly less. e amount

of taxes collected to pay voter-approved debt

varies considerably across the state. For example,

the average amount paid by an Alameda County

property owner for voter-approved debt rates is

about $2 for each $1,000

of assessed value, while

the average amount paid

in some counties is less

than 10 cents per $1,000 of

assessed value.

Limited Information

About Distribution

Of Other Property

Taxes and Charges

Less information

is available about the

statewide distribution of

the revenue from parcel

taxes, Mello-Roos taxes,

and assessments.

Parcel Taxes. Recent

election reports and

nancial data suggest that

parcel taxes represent a

signicant and growing

source of revenue for

some local governments.

Specically, between

2001 and 2012, local

voters approved about

180 parcel tax measures

to fund cities, counties,

and special districts, and

about 135 measures to

fund K-12 districts. e

most recent K-12 nancial

data (2009-10) indicate

that schools received

about $350million from

this source. We were not able to locate information

on the statewide amount of parcel tax revenue

collected by cities, counties, and special districts.

Mello-Roos Taxes. Mello-Roos districts are

required to report on their bond issuance, which

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 21

provides some information about the types of local

governments that receive Mello-Roos tax revenue.

It is likely that local governments issuing a large

amount of Mello-Roos bonds also are collecting a

large amount of Mello-Roos tax revenue. Between

2004 and 2011, cities issued about 50percent of the

bonds issued by Mello-Roos districts in California,

followed by K-12 districts at about 30percent.

During the same time period, the issuance of

Mello-Roos bonds was concentrated in specic

regions, as more than 60percent of the bonds were

issued by local governments in four counties—

Riverside, Orange, San Diego, and Placer.

Assessments. Most of the property

improvements funded by assessments are provided

by cities and special districts. In 2009-10, cities and

special districts reported receiving $760million

and $650million, respectively, in revenue from

assessments. In contrast, counties reported

$11million in such revenues.

WHY DO LOCAL GOVERNMENT

PROPERTY TAX RECEIPTS VARY?

e share of revenue received by each type of

local government from the 1percent rate varies

signicantly by locality. County governments, for

example, receive as little as 11percent (Orange) and

as much as 64percent (Alpine) of the ad valorem

property tax revenue collected within their county.

As shown in Figure 11, revenue raised from the

1percent rate also varies considerably by locality

when measured by revenue per resident. Orange

County receives about $175 per resident, while

four counties receive more than $1,000 per

resident. Although cities, on average, receive about

$240 per resident in revenue from the 1percent

rate, some receive more than $500 per resident

and many receive less than $150 per resident.

School districts also receive widely dierent

amounts of property taxes per enrolled student,

with an average of just under $2,000. (As noted

above, the state “tops o” school property tax

revenue with state funds to bring most schools to

similar revenue levels.) Finally, special districts

also receive varying amounts of property tax

revenue, though data limitations preclude us from

summarizing this variation on a statewide basis.

ree factors account for most of this

variation in local government property tax

receipts. We discuss these factors below.

Variation in Property Values

California has a diverse array of communities

with large variation in land and property values.

Some communities are extensively developed

and have many high-value homes and businesses,

whereas others do not. Because property taxes

are based on the assessed value of property,

communities with greater levels of real estate

development tend to receive more property

tax revenue than communities with fewer

developments. For example, high-density cities

generally receive more property tax revenue than

rural areas due to the greater level of development.

Coastal and resort areas also typically receive

more property taxes due to the high property

values. Certain high-value properties—such

as a power plant or oil renery—also increase

property tax revenue. Alternatively, localities

with large amounts of land owned by the federal

government, universities, or other organizations

that are not required to pay property taxes may

receive less revenue.

An LAO RepORt

22 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

Prior Use of Redevelopment

Prior decisions by cities and counties to use

redevelopment also inuences the amount of

property tax revenue local governments receive.

Prior to the dissolution of redevelopment agencies

in 2012, most of the growth in property taxes

from redevelopment project areas went to the

redevelopment agency, rather than other local

governments. A large share of property tax revenue

now goes to successor agencies to pay the former

redevelopment agencies’ debts and obligations. e

use of redevelopment varied extensively throughout

the state. In those communities with many

redevelopment project areas, the share of property

tax revenue going to other local governments is

less than it would be otherwise. In places with

large redevelopment project areas—such as San

Bernardino and Riverside counties—more than

20percent of the county’s property tax revenue may

go to pay the former redevelopment agencies’ debts

and obligations.

State Allocation Laws Reecting

1970s Taxation Levels

Finally, the amount of property taxes allocated

to local governments depends on state property

tax allocation laws, principally AB 8. As discussed

earlier in this report (and in more detail in the

appendix), the AB 8 system was designed, in part,

to allocate property tax revenue in proportion

to the share of property taxes received by a local

government in the mid-1970s. Under this system,

local governments that received a large share of

property taxes in the 1970s typically continue to

receive a relatively large share of property taxes

today. Although there have been changes to the

original property tax allocation system contained

in AB 8, the allocation system continues to be

substantially based on the variation in property tax

receipts in eect in the 1970s.

is variation largely reects service levels

provided by local governments in the 1970s. Local

governments providing many services generally

collected more property taxes in the 1970s to

Figure 11

Property Tax Receipts From the 1 Percent Rate for Selected Local Governments

2009-10

Cities

Property

Taxes per

Resident Counties

Property

Taxes per

Resident Schools

a

Property

Taxes per

Student

Industry $2,541 San Francisco

b

$1,411 Mono $10,683

Malibu 559 Sierra 1,126 San Mateo 5,432

Mountain View 344 Inyo 876 Marin 5,213

Los Angeles 332 Napa 522 San Francisco 4,020

Long Beach 268 El Dorado 464 Orange 3,315

Oakland 250 Los Angeles 359 San Diego 2,760

State Average 242 State Average 320 State Average 1,960

San Jose 200 Alameda 301 Yolo 1,765

Fresno 183 Sacramento 286 Sacramento 1,344

Anaheim 167 Contra Costa 271 San Joaquin 1,163

Santa Clarita 140 San Diego 261 Los Angeles 1,142

Chico 129 Riverside 200 Fresno 810

Modesto 119 Orange 174 Kings 379

a

Countywide average for K-12 schools.

b

San Francisco is a city and a county.

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 23

pay for those services. As a result, those local

governments received a larger share of property

taxes under AB 8. For example, cities and counties

that provided many government services, including

re protection, park and recreation programs, and

water services, typically receive more property tax

revenue than governments that relied on special

districts to provide some or all of these services.

ARE THERE CONCERNS ABOUT HOW

PROPERTY TAXES ARE DISTRIBUTED?

While no system for sharing revenues among

governmental entities is perfect, the state’s system

for allocating property tax revenue from the

1 percent rate raises signicant concerns about

local control, responsiveness to modern needs, and

transparency and accountability to taxpayers. We

discuss these concerns separately below and then

address the question: Could the state change the

allocation system?

Lack of Local Control

Unlike local communities in other states,

California residents and local ocials have

virtually no control over the distribution of

property tax revenue to local governments.

Instead, all major decisions regarding property tax

allocation are controlled by the state. Accordingly,

if residents desire an enhanced level of a particular

service, there is no local forum or mechanism

to allow property taxes to be reallocated among

local governments to nance this improvement.

For example, Orange County currently receives

a very low share of property taxes collected

within its borders—about 11percent. If Orange

County residents and businesses wished to expand

county services, they have no way to redirect

the property taxes currently allocated to other

local governments. eir only option would be

to request the Legislature to enact a new law—

approved by two-thirds of the members of both

houses—requiring the change in the property tax

distribution. In other words, local ocials have no

power to raise or lower their property tax share on

an annual basis to reect the changing needs of

their communities. As a result, if residents wish to

increase overall county services, they would need to

nance this improvement by raising funds through

a dierent mechanism such as an assessment or

special tax.

Limited Transparency and Accountability

e state’s current allocation system also makes

it dicult for taxpayers to see which entities receive

their tax dollars. Property tax bills note only that a

bulk of the payment goes to the 1percent general

levy. Even if taxpayers do further research and

locate the AB 8 local government sharing factors

for their TRA, it is dicult to follow the actual

allocation of revenue because the fund shis

related to ERAF and redevelopment complicate this

system.

In addition to making it dicult for

taxpayers to determine how their tax dollars are

distributed, the AB 8 system reduces government

accountability. e link between the level of

government controlling the allocation of the tax

(the state) and the government that spends the

tax revenue (cities, counties, special districts,

and K-14 districts) is severed. For example, if a

taxpayer believes the level of services provided by

an independent park district is inadequate, it is

dicult to hold the district entirely accountable

An LAO RepORt

24 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

because the state is responsible for determining the

share of property taxes allocated to the district.

Limited Responsiveness to Modern

Needs and Preferences

An eective tax allocation system ensures that

local tax revenue is allocated in a way that reects

modern needs and preferences. In many ways,

California’s property tax allocation system—which

remains largely based on allocation preferences

from the 1970s—does not meet this criterion.

California’s population and the governance

structure of many local communities have

changed signicantly since the AB 8 system was

enacted. For example, certain areas with relatively

sparse populations in the 1970s have experienced

substantial growth and many local government

responsibilities have changed. One water district

in San Mateo County—Los Trancos Water

District—illustrates the extent to which the state’s

property tax allocation system continues to reect

service levels from the 1970s. Specically, this water

district sold its entire water distribution system to

a private company in 2005, but continues to receive

property tax revenue for a service it no longer

provides.

Changing the Allocation System Is Dicult

Over the years, the Legislature, local

governments, the business community, and the

public have recognized the limitations inherent in

the state’s property tax allocation system. Despite

the large degree of consensus on the problems,

major proposals to reform the allocation system

have not been enacted due to their complexity and

the dicult trade-os involved. Because California

has thousands of local governments—many

with overlapping jurisdictions—reorienting

the property tax allocation system would be

extraordinarily complex. Updating the AB 8

property tax sharing methodology would require

the Legislature to determine the needs and

preferences of each California community and

local government. is would be a dicult—if not

impossible—task to undertake in a centralized

manner. Alternatively, the state could allow the

distribution of the property tax to be carried

out locally, but there is no consensus about what

process local governments would use to allocate

property taxes among themselves. Whether done

centrally or locally, any reallocation is dicult

because providing additional property tax receipts

to one local government would require redirecting

it from another local government or amending the

Constitution. In addition, any signicant change

to the allocation of property tax revenue would

require approval by two-thirds of the Legislature

due to provisions in the Constitution added by

Proposition1A (2004). (ese issues are discussed

further in the appendix.)

An LAO RepORt

www.lao.ca.govLegislativeAnalyst’sOfce 25

For many years, California’s overall property

tax system—the types of taxes paid by property

owners and the determination of property owner

tax liabilities—has evoked controversy. Some

people question whether the distribution of the

tax burden between residential and commercial

properties is appropriate and whether the amount

of taxes someone pays should depend, in part, on

how long he or she has owned the property. Other

people praise the nancial certainty that the tax

system gives property owners. From one year to

the next, property owners know that their tax

liabilities under the 1 percent rate will increase

only modestly. In this section, we do not attempt

to resolve this long-standing debate. Instead, we

review property taxes by looking at how they

measure according to ve common tax policy

criteria—growth, stability, simplicity, neutrality,

and equity. Using this framework, we highlight

particular aspects of the state’s property tax system,

both its strengths and limitations, for policymakers

and other interested parties.

Economists use the ve common tax policy

criteria summarized in Figure 12 to objectively

compare particular taxes. ese criteria relate to

how taxes aect people’s decisions, how they treat

dierent taxpayers, and how the revenue raised

from taxes performs over time. In practice, all

taxes involve trade-os. Sometimes the trade-os

are between two tax policy criteria. For example,

revenue sources that grow quickly may be less

stable from one year to the next than other revenue

sources. Other times, the trade-os are between

tax policy criteria and other governmental policy

objectives that may not be directly related to one

of the ve tax criteria. For example, one such

trade-o might be that ensuring that a property

owner’s taxes do not increase dramatically from

one year to the next (a reasonable governmental

policy objective) can result in a tax system in which

the owners of similar properties are taxed much

dierently (contrary to the equity criteria of tax

policy).

Revenue Growth

From government’s perspective, revenue sources

that grow along with the

economy are preferable

because they can provide

resources sucient to

maintain current services.

is can help governments

avoid increasing existing

taxes or taxing additional

activities in order to meet

current service demands.

e Property Tax

Has Grown Faster an

the Economy. Personal

income in California—an

WHAT ARE THE STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

OF CALIFORNIA’S PROPERTY TAX SYSTEM?

Figure 12

Common Economic Criteria for Evaluating Tax Systems

9 Growth—Does revenue raised by the tax grow along with the economy

or the program responsibilities it is expected to fund?

9 Stability—Is the revenue raised by the tax relatively stable over time?

9 Simplicity—Is the tax simple and inexpensive for taxpayers to pay and

for government to collect?

9 Neutrality—Does the tax have little or no impact on people’s decisions

about how much to buy, sell, and invest?

9 Equity—Do taxpayers with similar incomes pay similar amounts and do

tax liabilities rise with income?

An LAO RepORt

26 LegislativeAnalyst’sOfcewww.lao.ca.gov

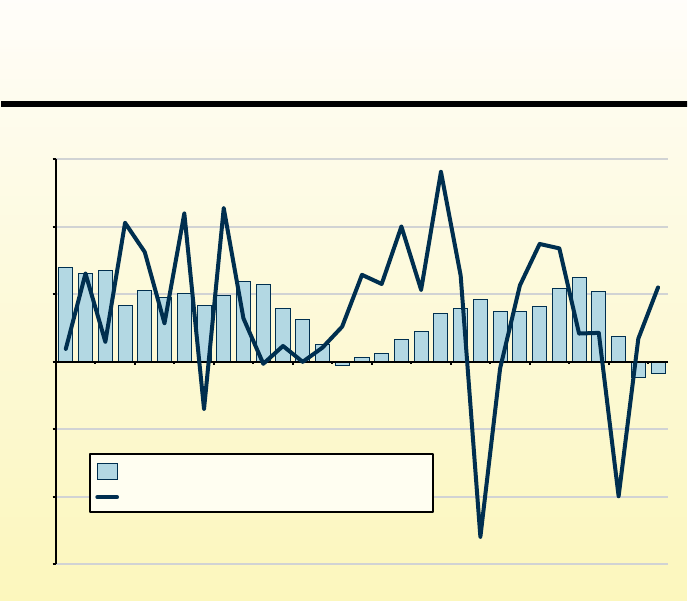

What Factors Aect Property Tax Growth Each Year?

Most of the annual change in property tax revenues is the result of large changes in assessed

value that aect a small number of properties, including:

• Recently Sold Properties. When a property sells, its assessed value resets to the purchase

price. is represents additional value that is added to the tax base because the sale price of

the property is oen much higher than its previous assessed value.

• Newly Built Property and Property Improvements. New value is added to the county’s tax

base when new construction takes place or improvements are made—mainly additions,

remodels, and facility expansions—because structures are assessed at market value the year

that they are built.

• Proposition 8 (1978) Decline-in-Value Properties. ese properties contribute signicantly

to growth or decline in a county’s tax base because their assessed values may increase or

decrease dramatically in any year. A particularly large impact on assessed valuation tends

to occur in years when a large number of these properties transfer from Proposition 13

assessment to reduced assessment.

As shown by the dark bars in the gure below, recently sold, newly built, and decline-in-value

properties typically account for more than two-thirds of total changes in countywide assessed value

in Santa Clara County. Other properties, although they represent most of the properties in the