Monitoring and

Evaluation in the

Development

Sector

A KPMG International

Development

AssistanceServices

(IDAS) practice survey

KPMG INTERNATIONAL

Foreword – Monitoring &

Evaluation (M&E) Survey

5

Survey highlights 6

Monitoring 8

Purpose of monitoring 9

Monitoring system effectiveness 9

Evaluation purpose 10

Evaluation priorities 10

Decision rules 11

Tracking outputs and outcomes 11

Evaluation management

and approaches 12

Institutional arrangements 13

Change in M&E approaches 14

Evaluation methodologies 15

Evaluation techniques 16

Strengths and weaknesses of

evaluation 17

Contents

Foreword – Monitoring &

Evaluation (M&E) Survey, 2014 4

Survey Highlights 6

Monitoring 8

Purpose of monitoring 9

Monitoring system effectiveness 9

Evaluation Purpose 10

Evaluation priorities 10

Decision rules 11

Tracking outputs and outcomes 11

Evaluation Management and Approaches 12

Institutional arrangements 13

Change in M&E approaches 14

Evaluation methodologies 15

Evaluation techniques 16

Strengths and weaknesses of evaluation 17

Use of New Technology 18

Roadblocks to using technology 19

Evaluation Feedback Loops 20

Timeliness of evaluations 16

Resources for Monitoring and Evaluation 16

Availability of M&E resources 16

Role Models in M&E 17

Methodology Case Study: Outcome mapping 18

Survey Methodology 19

Glossary 20

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Use of new technology 18

Roadblocks to using technology 19

Evaluation feedback loops 20

Timeliness of evaluations 20

Resources for monitoring

and evaluation 22

Availability of M&E resources 22

Role models in M&E 23

Methodology Case

Study: Outcome mapping 24

Survey methodology 27

Glossary 28

Bookshelf 30

Foreword – Monitoring &

Evaluation (M&E) Survey, 2014 4

Survey Highlights 6

Monitoring 8

Purpose of monitoring 9

Monitoring system effectiveness

9

Evaluation Purpose 10

Evaluation priorities 10

Decision rules 11

Tracking outputs and outcomes

11

Evaluation Management and Approaches 12

Institutional arrangements 13

Change in M&E approaches 14

Evaluation methodologies 15

Evaluation techniques 16

Strengths and weaknesses of evaluation

17

Use of New Technology 18

Roadblocks to using technology 19

Evaluation Feedback Loops 20

Timeliness of evaluations 16

Resources for Monitoring and Evaluation 16

Availability of M&E resources 16

Role Models in M&E 17

Methodology Case Study: Outcome mapping 18

Survey Methodology 19

Glossary 20

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

4

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Timothy A. A. Stiles

Global Chair, IDAS

Trevor Davies

Global Head, IDAS Center of Excellence

We are pleased to present findings from KPMG’s Monitoring and Evaluation

(M&E) Survey, which polled more than 35 respondents fromorganizations

responsible for over US$100 billion of global development expenditure.

The survey reflects perspectives from M&E leaders on the current state,

including approaches, resources, use of technology and major challenges

facing a variety of funders and implementers.

At a time of increasing public scrutiny of development impacts, there

is increased focus in many development agencies on M&E tools and

techniques. The objective of KPMG’s M&E Survey was to understand

current approaches to M&E and their impact on project funding, design, and

learning. More effective M&E is necessary to help government officials,

development managers, civil society organizations and funding entities to

better plan their projects, improve progress, increase impact, and enhance

learning. With an estimated global spend of over US$350billion per annum

on development programs by bilateral, multilateral, and not-for-profit

organizations, improvements in M&E have the potential to deliver benefits

worth many millions of dollars annually.

Our survey reveals a range of interesting findings, reflecting the

diversity of institutions consulted. Common themes include:

• A growing demand to measure results and impact

• Dissatisfaction with use of ndings to improve the delivery of new

programs

• Resourcing as an important constraint for many respondents

• New technology is still in its infancy in application

On behalf of KPMG, we would like to thank those who participated

in this survey. We hope the findings are useful to you in addressing

the challenges in designing and implementing development projects

and also to build on the lessons learned. By enhancing the impact and

delivery of development projects, we can all help to address more

effectively the challenges facing developing countries.

Foreword

Monitoring & Evaluation

(M&E) Survey

KPMG [“we,” “our,” and “us”] refers to the KPMG IDAS practice, KPMG International, a Swiss entity that serves as a

coordinating entity for a network of independent member firms operating under the KPMG name, and/or to any one or

more of such firms. KPMG International provides no client services.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

5

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

No clear consensus on

terminology or approach

Survey respondents used divergent organizational definitions of

various M&E terms. This is potentially problematic for both donors

and implementers for a variety of reasons, including lack of clarity on

monitoring approaches and evaluation techniques. (See Glossary for

terminology used in this report).

Availability of more

sophisticated evaluation

models and techniques

doesn’t guarantee their use

Although there are a wide range of evaluation techniques available,

ranging from the highly technical (such as counterfactual studies) to the

innovative, (such as Social Return on Investment (SROI)), our survey

indicates that the most widely used techniques are in fact quite basic.

The top three techniques used are:

1. “Logical frameworks”

2. “Performance indicators” and

3. “Focus groups”

Need for stronger and

more timely feedback

loops to synthesize and

act on lessons learned

Project improvement and accountability to funders drives the

motivation for monitoring projects. The vast majority of respondents

said they monitor projects for project improvement, and also said that

they carry out evaluations to ensure that lessons are learned and to

improve the development impact of their projects.

However, over half of respondents identified “Changes in policy and

practice from evaluation” as “poor” or “variable” and nearly half of all

respondents identified as a weakness or major weakness the ability of

their “Feedback mechanisms to translate into changes.”

This presumably means that reports are produced but they are not acted

upon often enough or in a timely fashion, representing a missed opportunity.

Adoption of new

technologies is lagging

The use of innovative technologies, such as mobile applications, to

address international development challenges has gained recent

attention. When asked about use of technology to collect, manage and

analyze data, the vast majority of respondents said that “Information

and Communication Technology enabled visualizations” were “never”

or “rarely” used; and almost as many respondents indicated that “GPS

data,” a relatively accessible technology, was never or rarely used.

This means that M&E is still a labor-intensive undertaking.

Lack of access to quality

data and financial

restrictions are the

key impediments to

improving M&E systems

Over half of respondents identified a lack of financial resources as a

major challenge to improving the organization’s evaluation system.

A similar majority of respondents estimated levels of resourcing for

evaluation at 2 percent or less of the program budget, which many

survey respondents indicated to be inadequate.

Survey

highlights

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

6

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Policy implications and recommendations

Development organizations should expand their use of innovative

approaches to M&E, using information and communication technology

enabled tools to harness the power of technology to reduce the costs of

gathering real-time data.

Development organizations need to strengthen feedback from evaluation

into practice through rapid action plans, with systematic tracking, and

more effective and adequately resourced project and program monitoring

practices and systems.

It is a false economy to underinvest in M&E as the savings in M&E costs

are likely to be lost through reduced aid and development effectiveness.

Organizations should monitor the M&E expenditure as a share of program,

and move towards industry benchmarks where spending is low.

Standardized terminology and approaches, such as that provided

by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) Development Assistance Committee, should be applied within

nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and philanthropic organizations, in

order to standardize and professionalize approaches to M&E.

Evaluation approaches in NGOs are driven by donors without adequate

harmonization of approaches and joint working. Donors should apply the

principles of harmonization not just to developing countries, but also to NGO

intermediaries, both to reduce the administrative burden and to allow a more

strategic and effective approach.

Evaluation systems should include opportunities for feedback from primary

beneficiaries.

Project evaluations should be synthesized appropriately through adequate

investment in sector and thematic reviews and evaluations.

Fully independent evaluation organizations or institutions provide an

effective model to professionalize and scale up evaluation work, with

appropriate support from independent experts.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

7

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Monitoring

Achieving maximum development impact is high among the

priorities for monitoring, but challenges remain in using information

to improve program delivery. Less than half the respondents stated

that organizations always or very frequently update targets and

strategies, and in less than 40 percent of cases do organizations

always or very frequently produce clear action plans with follow-up.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

8

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Purpose of monitoring

Question: What is the key focus of the organization in project monitoring?

The most important purposes of monitoring are for project improvement

(91percent of respondents) and accountability to funders (87percent).

Organizations are more aware of monitoring accountability to funders than to

their own internal boards. It is also striking, in the current climate, that value

for money is accorded a relatively lower priority for monitoring information than

most other motivations.

Monitoring data is seen as a very

important input to evaluation,

but since the data are not often

there, its use is limited.

Compliance

Value for Money

Accountability to board

Portfolio performance management

91%

87%

75%

68%

66%

50%

48%

Project Improvement

Accountability to funders

Impact Measurement

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 1: “Most important” or “Very important” monitoring objectives

Monitoring produces clear action

plans with appropriate follow-up

Primary beneficiaries and

stakeholders consulted annually

68

%

61%

48%

45%

45%

39%

35%

Projects monitored with

plans at inception

Monitoring results aggregated

Monitoring results in updated

targets and strategies

Monitoring plans integrated with

evaluation framework

Programs teams have sufficient

staffing and travel resources

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 2: “Always” or “Very frequently” used monitoring attributes

Monitoring system effectiveness

Question: How would you assess the monitoring system of your organization?

The basics of the monitoring system are functional in most of the organizations

covered. The strengths of monitoring systems include monitoring in line with

project plans at inception and aggregation of monitoring results. Relative challenges

include lack of sufficient staffing and resources, and the failure to produce clear

action plans with appropriate follow-up to ensure that issues identified during

monitoring are effectively actioned.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

9

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Evaluation

purpose

Learning is the most important

objective. However, the

Directorate would say that

showing politicians we are

effective to secure future

funding is paramount.

Development Impact Focused

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 3: “Most important” or “Very important” evaluation objectives

To ensure lessons are learned

from existing programs

To improve

development impact

To provide evidence

for policy makers

To pilot the effectiveness

of innovative approaches

To improve value for money

To attract additional funding

To improve transparency

and accountability

To meet donor demands

To meet statutory demands

To meet board or trustee requirement

To show taxpayers aid is effective

Accountability Focused

85%

82%

71%

70%

55%

45%

48%

57%

75%

79%

52%

Evaluation priorities

Question: What are the main reasons why your organization conducts formal

evaluations?

Eighty-five percent of respondents indicated that learning lessons was a

key motivation for evaluation, followed closely by 82 percent that identified

development impact. Relatively less emphasis is given to accountability to

taxpayers and trustees, and attracting additional funding. Operational effectiveness

is the more dominant reason why organizations undertake evaluation. In terms of

accountability, improving transparency and accountability dominate; however, some

organizations struggled to rank effectiveness above accountability.

There are many factors which influence why organizations

undertake evaluations of their activities, and these are not mutually

exclusive. Broadly speaking these are focused around operational

effectiveness, and external accountability to different constituencies.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

10

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

you follow when deciding when/

re they?

how their organizations approach the

undertaken, reflecting the diverse

Under the current driv

Results Based Manag

we are pushing our sta

focus more keenly on t

outcome level. They ha

stuck in the activity-to-

Decision rules

Question: Are there decision rules which

how to invest in evaluation? If yes, what a

Respondents indicated a variety of reasons for

question of when and whether evaluations are

nature of institutions and contexts.

Decisions are based on factors such as:

• Required on all projects

• Demands from donors

• Government rules

• Project plans

• Evaluation strategies

• Undertaken as best practice

Tracking outputs and outcomes

Question: Do you aim to evaluate outputs or outcomes?

Most respondents indicated that they look to evaluate both outputs and

outcomes. Some organizations are able to carry out the full M&E cycle from

monitoring outputs to evaluating outcomes to assessing impact. Issues such as

lack of availability of data or differing donor requirements can constrain this.

e for

ement,

ff to

he

ve been

output

process for toolong.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

11

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Evaluation

management and

approaches

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Most large organizations have a mixed approach to managing

evaluations in order to combine the advantages of centralized and

decentralized approaches.

Institutional arrangements

Question: Which parts of the organization are responsible for monitoring and

evaluation (country office, program team, HQ evaluation specialists, independent

evaluation office, external contractors, others)? Can you describe how the overall

evaluation work in the organization is divided between these different groups

either by type of work or by amount of work in the area of evaluation?

Evaluations can be conducted at different levels including evaluations by the primary

beneficiaries themselves, evaluations by the program teams, and evaluations

by a central evaluation team. They can also be undertaken by an independent

evaluation office or commissioned from consultants, though less than half of

respondents reported that they always or very frequently do so. Nevertheless, the

more frequently used evaluation approaches include commissioned consultancy

evaluations and program team evaluations. Fully independent evaluations and self

evaluation by grantees are less often used.

64

%

33%

55%

17%

45%

34%

30%

48%

34%

43%

Self evaluation by

grantees/recipients

Independent Evaluation

Office/Institutions

Program Team

Evaluations

Rarely/Never

Commissioned

Consultancy Evaluations

Central Evaluation

Team/Dept (internal)

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 4: Frequency of use of monitoring mechanisms

Always/Very frequently

Question: Which mechanisms are used to conduct formal evaluations?

Around a third of the respondents indicated that a central evaluation team or

department would evaluate projects very frequently, or always. This approach

brings greater accountability to the evaluation process as well as a basis

to compare performance across the organization. It should also allow the

deployment of greater expertise.

Evaluation is decentralized to

teams and commissioned and

managed by them with advisory

support from the central

evaluation department.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

13

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Question: How does this distribution mirror the way in which the organization is

structured (e.g., centralized, decentralized)?

Generally, the responses confirm that organizational structure mirrors the

centralized and decentralized aspects of the M&E system. The majority of

respondents focused on the decentralized nature of both their evaluation approach

and their organizational delivery model with some notable exceptions.

Change in M&E approaches

Question: What is changing in your organization’s approach to monitoring and

evaluation?

Some of the key messages are a growing demand for evidence, strengthening

of the evaluation system, improved monitoring, and increased interest in impact

measurement. There is a growing emphasis on building the evidence base for

programs through evaluation in many organizations. Some respondents gave a

strong account of having deliberately embedded a results-based approach in their

organization.

• “Recognition of the need for an evidence base is

increasing.”

• “Demand for regular reporting to the board is increasing.”

• “Internally we are sick of not being able to say what

difference we have made.”

• “A shift towards greater focus on building the evidence

base.”

Growing

Demand for

Evidence

• “We have pushed up both the oors and ceilings of

evaluation standards in the organization. What was

previously our ceiling (gold standard) is now our floor

(minimum standard).“

• “A more strategic approach is planned so evidence

gaps are identified more systematically and better

covered by evaluation.”

Evaluation

Systems

Strengthening

• “We are working on getting more sophisticated in

our use of monitoring data so we have better and

timelier feedback information loops.”

• “We are implementing changes to improve

monitoring and how we use monitoring data.”

Improved

Monitoring

Approaches

• “Evaluation has moved from only addressing

performance issues to addressing impact issues.”

• “We have identied some innovative programs which

we design with leading universities or academics

where we feel the contribution to global knowledge

is important, and where the rigor of the design and

M&E needs to be top notch.”

More Focus

on Impact

Measurement

Every key person in the

program is involved in

ensuring that implementation

of research projects is geared

towards realizing the impact

we are seeking to achieve

and they monitor and collect

evidence of outputs and feed

them to the M&E section.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

14

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Evaluation methodologies

Question: What type of evaluation does your organization currently use and how frequently?

Project evaluations are the most frequently used compared to other methodologies. Impact, sector,

and risk evaluations are used relatively rarely in most organizations.

69%

33%

26%

25%

25%

25%

17%

14%

Project evaluation

Participatory evaluations

Country program evaluation

Self-evaluations

Thematic evaluation

Impact evaluation

Sector evaluation

Risk evaluations

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 5: “Always” or “Very frequently” used evaluation types

Question: Which type of evaluation would you like your organization to do more of?

Few techniques are considered to be overused. Respondents report that there is a need to increase

the use of country program, sector, participatory, and impact evaluations. The cost of certain types of

evaluations can also impact choice.

66

%

65%

56%

54%

53%

48%

43%

14%

Country program evaluation

Participatory evaluations

Risk evaluations

Thematic evaluation

Impact evaluation

Sector evaluation

Self evaluations

Project evaluation

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 6: “Underused” or “Very underused” evaluation types

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

15

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Evaluation techniques

Question: Which evaluation techniques does your organization currently use, and

how frequently?

The survey encountered a divergence in the frequency of techniques used for

evaluation, with relatively low emphasis on quantified techniques which involve a

counterfactual analysis with potential attribution of impact. This is understandable, but

does reflect the challenge of quantified reporting of impact in the development field.

Techniques such as tracking a theory of change and ‘results chains’ are more frequently

used and will give some explanation of how interventions are having an impact.

Performance indicators and logical frameworks are the most frequently used

techniques. Organizations are not frequently using techniques of SROI, Cost Benefit

Analysis, and Return on Investment.

11%

77%

75%

48%

48%

47%

43%

42%

41%

27%

17%

15%

11% 11%

70%

58%

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 7: “Very Frequently” or “Always” used evaluation techniques

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

75%+

50-75% 25-50% 0-25%

L

ogical frameworks

Performance indicators

Focus groups

Baseline studies

Participant analysis

Indirect/proxy indicators

Beneficiary feedback

Results chains

Theory of change

Risk analysis

Performance benchmarking

Results attribution

Social return on investment

Return on investment

Cost benefit analysis

Counterfactual studies

Randomized control trials

0%

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

16

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Strengths and weaknesses of

evaluation

Question: What would you say are the main strengths and weaknesses of your

organizational approach to evaluation?

Although there is high confidence in the rigor of measurement for evaluation,

there are perceived weaknesses in other areas. A lack of financial resources is

perceived as a major challenge to improving evaluation systems. Most respondents

(61percent) indicate strong external scrutiny as a major strength. No other feature

was reported as a major strength by the majority of respondents. Three major

weaknesses were identified by at least 40 percent of respondents in the areas of

measurement, timeliness, and, most commonly, overall feedback mechanisms.

Rigorous Measurement

Timeliness – speed in

finding what is not

working and working

Feedback mechanisms –

findings are effectively

translated to changes

Overall levels of

investment and frequency

–

sufficient evaluation activity

Quality assurance – high

quality of evaluation work

Level of independence –

strong external scrutiny

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 8: "Weaknesses" or "Major Weaknesses" and "Strengths" or

"Major Strengths" of Evaluation

21%

42%

15%

41%

38%

47%

42%

27%

44%

61

%

19%

19%

Major strength Major Weakness

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

For us, evaluation is a work in

progress.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

17

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Use of new

technology

18

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

The use of new technology in M&E appears to lag behind other

sectors of development which have more readily adopted new

technologies including mobile-based solutions, crowd-sourcing,

and location-based reporting applications. Organizations appear

to be limited in their use of Information and Communication

Technology (ICT) enabled tools due to challenges accessing data

and getting meaningful information from the analysis provided by

these tools.

Question: Which information and communication technology enabled tools

do you use to collect, manage and analyze data for monitoring and evaluation

purposes?

The extent of new technology applications in development evaluation is as yet in

its relative infancy. Data techniques are “rarely” or “never” used by the majority

of respondents (see Figure 9), with Web-based surveys being the most frequently

used technique. Some organizations are also developing data entry systems using

tablets and mobile phones. Accessing data is a major challenge for a majority of

respondents.

Roadblocks to using technology

Question: What would you say are the main challenges and problems in

introducing data analytics and “big data” into your evaluation system?

Access to expertise, cost of data management and analysis, ease of data

accessibility and standardization, and the use of technology by beneficiaries in the

field were identified as key factors that impeded greater adoption of technology.

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 9: “Rarely” or “Never” used ICT enabled tools

VideoICT enabled

visualization

GPS data Audio Media

monitoring

Mobile based

(e.g., SMS)

Open source

database

Web-based

surveys

91% 83% 82% 81%

72%

69%

57% 54%

72

%

Accessing data

Getting meaningful

information from

the analysis

Processing data

Accessing skilled

personnel

Accessing financial

resources

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 10: “Major” or “Substantial” challenges in introducing data analytics and ”big data”

69%

55%

55%

52%

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

The use of big data is a great idea

but our staff are cynical about

the reliability and veracity of

government generated data in

poorly governed countries.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

19

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Question: How effective would you say the feedback mechanisms are

between evaluation findings and operational performance/strategy?

Analyzing feedback is generally scored as poor or variable in the majority of

cases. In four of the five categories, more than half the responses were “poor”

or “variable.” The score for “internalizing evaluation feedback” is, however,

less negative than the more detailed examples, which focus on what would

beinvolved in generating such feedback.

Evaluation

feedback loops

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 11: “Poor” or “Variable” assessments of feedback mechanisms

59%

53%

52%

52%

36%

Analysis of emerging patterns and trends

Reporting externally on evaluation follow-up

Synthesis of evaluation lessons

Changes in policy and practice from evaluation

Internalizing evaluation feedback

A commonly expressed concern about evaluation is that

the feedback loops are very slow. By the time a particular

intervention has been implemented and evaluated, the

organizational priorities and approaches may have moved on,

meaning the relevance of evaluation is marginal. For this reason,

it may be better to give more priority and resources on effective

monitoring than on ex post evaluation.

Timeliness of evaluations

Question: How long does it take for the results of an evaluation to result in

improvements in current and future programs?

Most respondents (66 percent) felt that it would take less than a year for the results

of an evaluation to lead to improvements. Few respondents identified timeliness as

a strength of their evaluation system. It is important to appreciate that the question

refers not to the whole project cycle, but only to the period between a completed

evaluation and the lessons from that evaluation being applied at a project level.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

The better the evaluation

product and the more

stakeholder involvement

during the process, the better

the uptake at all levels.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

20

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

• Multicountry/Multilingual projects take longer to absorb

the lessons of particular evaluations, especially when

considering complex projects

• Meta-evaluations on a given sector or a particular

approach are undertaken on a five-year cycle so the

lesson learning and policy feedback loop can take that

entire length of time.

Sample

reasons for

length of time

of feedback

loops:

(numbers do not sum to 100 due to rounding)

Less than

3 months

3 – 6

months

6 months

– 1 year

1 – 2

years

More than

2 years

Figure 12: Time for evaluation results to lead to performance improvements

10% 28% 28% 21% 14%

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

21

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

A common theme of a number of questions in the survey is that

lack of resources is a major constraint or challenge.

Availability of M&E resources

Question: What proportion of program budget would you say is being spent

on monitoring and evaluation?

The majority of respondents (53 percent) stated that levels of resourcing for

evaluation were 2 percent or less of the program budget.

Resources

for monitoring and evaluation

(Estimated spending on M&E as % of program budget)

Percent of program budget

1%

Figure 13: Proportion of program budget being spent on M&E

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

25%

28% 28%

6% 6% 6%

2% 3-5% 6-7%

8-9% 10%+

55

%

Lack of financial

resources

Lack of access to

data and information

Inability to hire

good consultants

Inability to recruit staff

Lack of robust

methodlogies

(multiple responses allowed)

Figure 14: Main challenges and problems in improving evaluation systems

38%

30%

27%

24%

Question: What would you say are the main challenges and problems in

improving your evaluation system?

Lack of financial resources is the most frequently cited challenge to strengthening

the evaluation system. Nearly a quarter of respondents estimated the evaluation

budgets to be 1 percent or less of program spend. The share of respondents

estimating the evaluation budget at more than 5 percent of program budget is fewer

than one in five (19 percent).

(numbers do not sum to 100 due to rounding)

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Availability of financial

resources is usually a

challenge which in turn

has consequences in the

application of more robust

methodologies for better

evaluation practices.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

22

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Role models in M&E

Although responses to a question about role models were quite varied,

multilateral banks and the health sector were consistently ranked as leaders in the

development sector.

Question: In your opinion which organization has the strongest monitoring

and evaluation approach?

The most admired organizations were praised with regard to the strength, quality,

and data-driven nature of their approach to monitoring and evaluation by their peers.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

23

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Outcome Mapping (OM) is an alternative planning and results

evaluation system for complex development interventions. Key to

the success of this system has been the ability to adapt it in creative

ways to meet an individual program’s needs.

What is it?

One of the most important attributes of the OM method is its ability to track a breadth

of activities – both planned and opportunistic, and capture a range of results – from the

incremental to the transformative, across a variety of stakeholders. This is in contrast to

more conventional systems of results measurement, where the focus is narrowed to a

task of measuring planned activities, and using predefined indicators to chart high-level

results.

How does it work?

OM begins by identifying “boundary partners”: influential people, organizations,

institutions or other entities with whom a program will work to achieve its goals. These

partners might be politicians, community leaders or the media.

Progress towards goals is then tracked in terms of observed changes in behavior among

these boundary partners. Practitioners are asked to record small changes that they

observe every day in “outcome journals,” which enables them to capture a range of

evidence from the seemingly small to the transformative. This also allows practitioners

the freedom to capture whatever information best illustrates the change – as opposed to

collecting information against specific predefined indicators, as is done with a log-frame.

Methodology

Case Study:

Outcome Mapping

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

24

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Adapting OM: The Accountability in Tanzania (AcT) Program

Funded by DFID and hosted by KPMG in East Africa, the US$52 million Accountability

in Tanzania (AcT) program provides a useful example of how OM methodologies can be

applied creatively to facilitate flexible, impact-driven development programming. AcT

provides flexible grant funding to 26 civil society organization (CSOs) working to improve

accountability of government in Tanzania.

• AcTdevelopednewresultsmeasurementindicatorsthat

allowed it to merge its CSO-level OM data with the program’s

overall logframe in order to demonstrate, from top to bottom,

how change actually happens.

• AcTdevelopedadatabasethroughwhichtomanageitsOM

results. Database analysis has allowed AcT to develop a

clearer view of the results pathways for the program, report

results easily to DFID, and develop much more precise

progress markers to facilitate further learning.

• OMhasprovidedaneffectivebasisforstructuringand

monitoring AcT’s partnerships with CSOs – in order to gauge

the extent to which AcT support is helping to achieve a

strengthened civil society in Tanzania.

In order to

facilitate its

innovative

approach to

grant-making,

AcT has

adapted

outcome

mapping to

meet its needs

in a variety of

ways.

25

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

26

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

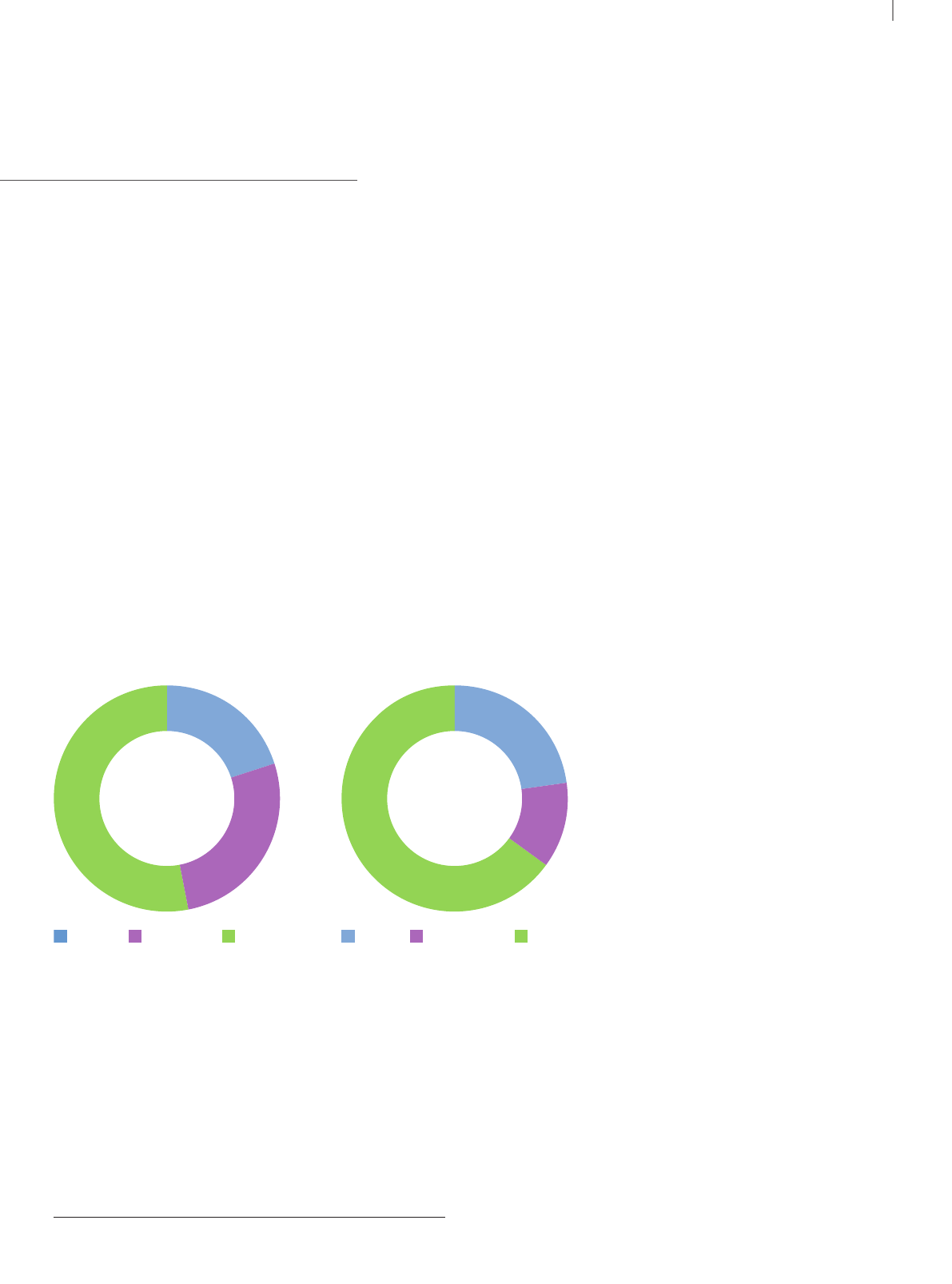

In carrying out this survey, we define monitoring as the activity

that is concerned with the review and assessment of progress

during implementation of development activities and projects.

This provides ongoing feedback to managers and funders about

performance – what is working and what is not working, and

needs correcting.

In contrast, “evaluation is the episodic assessment of the change in targeted results

that can be attributed to the program/project intervention, or the analysis of inputs and

activities to determine their contribution to results.”

1

KPMG’s Monitoring and Evaluation Survey reflects the responses of 35participants

during February through April 2014. Respondents’ organizations are responsible for

over US$100 billion of development spend.

2

The purpose of the survey was to identify current trends and opinions of those

who are leading the agenda within key development institutions. The survey was

completed using an online survey tool, supplemented in most cases by a telephone

interview to clarify responses and allow opportunity for dialogue. The following

types of organizations participated.

Survey

methodology

1

http://info.worldbank.org/etools/docs/library/243395/M2S2%20Overview%20of%20Monitoring%20and%20evaluation%20%20NJ.pdf slide, 15 March 2014.

2

KPMG estimate based on published information

Participant Type Role

Bilateral Multilateral Philanthropic

20%

Funder Implementer Both Funder and Implementer

27%

53%

65%

12%

23%

Source: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector, KPMG International, 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

27

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Glossary

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

28

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Accountability

The obligation to account for activities, accept responsibility for them, and to disclose the res

in a transparent manner

Baseline Study Analysis of the current situation to identify the starting point for a project or program

Beneficiary

Feedback

Monitoring through obtaining information from the primary stakeholders who benefit or are

intended to benefit from the project or program

Compliance Evaluation to comply with internal or external rules or regulations

Cost Benefit

Analysis

Quantification of costs and benefits producing a discounted cash flow with an internal rate of

return or net present value

Counterfactual

Study

A study to estimate what would have happened in the absence of the project or program

Evaluation

An assessment, as systematic and objective as possible, of an ongoing or completed project,

program or policy, its design, implementation and results

Focus Group

A focus group is a form of qualitative research in which a group of people are asked about th

perceptions, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes

Funder

An organization which provides financial support to a second party to implement a project or

program for the benefit of third parties

ICT Enabled

Visualization

Use of computer graphics to create visual means of communication and consultation with

stakeholders and beneficiaries

Impact

Measurement

The process of identifying the anticipated or actual impacts of a development intervention, o

those social, economic and environmental factors which the intervention is designed to affec

may inadvertently affect

Impact Evaluation

Assesses the changes that can be attributed to a particular intervention, such as a project,

program or policy, both the intended ones, as well as unintended ones

Implementer The organization which is responsible for delivery/management of a development interventio

Independent

Evaluation

An evaluation which is organizationally independent from the implementing and funding

organizations

Key Performance

Indicators

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) define a set of values used to measure against. An organiz

may use KPIs to evaluate its success, or to evaluate the success of a particular activity in whi

is engaged

Logical Framework

A tool which sets out inputs, outputs, outcomes and impact for an intervention with indicator

achievement, means of verification and assumptions for each level

Monitoring

The process of gathering information about project performance and progress during its

implementation phase

Open Source

Database

Open source software is computer software that is distributed along with its source code – t

code that is used to create the software – under a special software license

Outcome Mapping

An alternative planning and results evaluation system for complex development interventions

which tracks planned and unplanned outcomes (See Case Study)

Participatory

Evaluation

Provides for the active involvement of those with a stake in the program: providers, partners,

beneficiaries, and any other interested parties. All involved decide how to frame the questio

used to evaluate the program, and all decide how to measure outcomes and impact

ults

eir

n

t or

n

ation

ch it

s of

he

ns

Participant

Analysis

A range of well-defined, though variable methods: informal interviews, direct observation, participati

in the life of the group, collective discussions, analyses of personal documents produced within the

group, self-analysis, results from activities undertaken offline or online, and life histories

Performance

Benchmarks

Benchmarking is the process of comparing processes and performance metrics to industry

bests or best practices from other industries. Dimensions typically measured are quality, time

and cost

Portfolio

Performance

Metrics which enable organizations to measure the performance of different elements of their

portfolio and the portfolio overall

Primary

Beneficiary

The individual people that the project is intended to assist

Program Team

The department or team which is responsible and accountable for a particular project or

intervention

Project

A discrete set of activities which are generally approved as a package or series of packages, wit

defined objectives

Project Evaluation An evaluation which examines the performance and impact of a single intervention or project

Proxy Indicators An appropriate indicator that is used to represent a less easily measurable one

Randomized

Control Trials

An evaluation which assigns at random a control group and a treatment group. Comparison of t

performance of the two groups provides a measure of true impact

Results Chain

A Results Chain is a simplified picture of a program, initiative, or intervention. It depicts the logi

relationships between the resources invested, activities that take place, and the sequence of

outputs, outcomes and impacts that result

Results Attribution Evaluation techniques which attribute the specific outcomes and impacts of an intervention

Return on

Investment

A measure of the financial or economic rate of return, typically calculated through discounted

case flow analysis as an internal rate of return

Risk Analysis Assessment of the probability and impact of the risks affecting an intervention or project

Risk Evaluation

A component of risk assessment in which judgments are made about the significance and

acceptability of risk

Sector Evaluation

Evaluation of a set of interventions within a particular sector such as education,

health, etc.

Self Evaluation

An evaluation which is undertaken by the team which is responsible for the implementation of

that intervention

Social Return on

Investment (SROI)

SROI is an approach to understanding and managing the value of the social, economic and

environmental outcomes created by an activity or an organization. It is based on a set of principl

that are applied within a framework

Thematic

Evaluation

Evaluation of a set of interventions within a particular thematic approach such as governance or

gender

Theory of Change

An explicit presentation of the assumptions about how changes are expected to happen within

any particular context and in relation to a particular intervention

Value for Money ”The optimal use of resources to achieve intended outcomes”

3

on

h

he

cal

es

3

http://www.nao.org.uk/successful-commissioning/general-principles/value-for-money/assessing-value-for-money/, 23 August 2014.

Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

29

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Bookshelf

Sustainable Insight: Unlocking

the value of social investment

This report is intended to help corporate

responsibility managers and others

involved in designing and delivering social

investments to overcome some of the

challenges to measuring and reporting on

social programs.

Other publications

2013 Change Readiness Index

The Change Readiness Index assesses

the ability of 90 countries to manage

change and cultivate the resulting

opportunity.

Thought Leadership

Future State 2030: The

global megatrends shaping

governments

This report identifies nine global

megatrends that are most salient to

the future of governments. While their

individual impacts will likely be far-

reaching, the trends are highly interrelated

and thus demand a combined and

coordinated set of responses.

You can’t do it alone

This article explores the various demand

side and supply side measures to tackle

the youth unemployment crisis in both

developed and developing markets.

International Development Assistance Services (IDAS)

INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

ASSISTANCE SERVICES (IDAS)

kpmg.com/IDAS

You can’t do it alone:

Partnerships the only way to help the world’s young job seekers

As leaders and young people around the world are acutely aware, youth unemployment levels are already

disturbingly high and the problem is getting worse. An exploding youth population

1

and lag in job growth are key

causes. Population pressures from increasing numbers entering the labor market every year, particularly in Africa

and Asia, create opportunities for ‘demographic dividends’, but in turn will only continue to drive the need for higher

levels of job creation. Other factors such as the global financial crisis, the 2009 Eurozone crisis, and longer term

trends in global trade, technology, and competition, have also increased pressure points on this crisis.

30%

are not in employment,

education, or training

(NEETs)

2

, which translates

to

358M young people.

In Namibia, Saudi Arabia

and South Africa, nearly

9 out of 10 youth is outside

of the labor force.

5

a global

concern

This is

341M are in

developing countries

220M are in Asia

Of these:

(looking for work)

3

are unemployed

75 million

nearly

= 10 million

Every year, it is estimated that over

120 million

16 years

= 20 million

adolescents reach

to enter the labor market.

4

Greece and Spain had youth

unemployment rates of over

50 percent in 2013.

7

In the

US, it was over 15 percent.

Unemployment rates for young

women are higher than for

young men in Latin America

and the Caribbean, South Asia

and South-East Asia and

the Pacific.

6

Out of 1.2 billion youth aged 15 to 24:

of age and are looking

Source: KPMG International, 2014.

A complex issue of epic proportions

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Issues Monitor – A greener

agenda for international

development

This publication explores the nexus

between climate change and

development – an undeniable link

that demands greater alignment and

integration of both development and

climate change agendas in order to help

catalyze real and sustainable change

around the world.

IDAS ISSUES MONITOR

A greener agenda

for international

development

etamilc neewteb suxen ehT

change and development

kpmg.com

KPMG INTERNATIONAL

Issues Monitor –

Aid effectiveness

Developing countries have long

depended on humanitarian and

development aid provided by donor

countries and organizations. The

economic downturn and the resulting

strain on budgets have put donors under

extra pressure to demonstrate results.

KPMG INTERNATIONAL

Issues Monitor

Aid effectiveness –

Improving accountability

and introducing new

initiatives

November 2011, Volume Four

kpmg.com

Issues Monitor

Issues Monitor –

Bridging the gender gap

This publication explores the issue

of gender equality - something that

remains elusive in many parts of the

world, but is vital for economic growth

and development of society.

KPMG INTERNATIONAL

Issues Monitor

Bridging the

gender gap

Tackling women’s

inequality

October 2012, Volume Six

kpmg.com

Issues Monitor –

Ensuring food security

As people in developing countries

struggle to purchase enough food to

fulfill their daily nutrition requirements,

the number who continue to go

hungry remains high. Climate change

and crop diversion to biofuels have

increased pressure on food production,

contributing to higher worldwide food

prices. More global financial support to

strengthen supply systems is required

to help ensure that every person has

sufficient access to food.

KPMG INTERNATIONAL

Issues Monitor

Ensuring food security

September 2011, Volume Three

kpmg.com

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated.

Global Chair

Government & Infrastructure

Nick Chism

T: +44 20 7311 1000

E: nick.c[email protected]

Contact IDAS

Global Chair

Timothy A.A. Stiles

T: +1 212 872 5955

E: taastiles@kpmg.com

IDAS Center of Excellence

Trevor Davies

T: +1 202 533 3109

Central America

Alfredo Artiles

T: +505 2274 4265

CIS

Andrew Coxshall

T: +995322950716

East Asia and Pacific Islands

Mark Jerome

T: +84 (4) 3946 1600

Eastern Europe

Aleksandar Bucic

T: +381112050652

European Union Desk

Mercedes Sanchez-Varela

T: +32 270 84349

E: msanc[email protected]

Francophone Africa

Thierry Colatrella

T: +33 1 55686099

Middle East

Suhael Ahmed

T: +97165742214

North America

Mark Fitzgerald

T: +1 703 286 6577

E: markfitzgerald@kpmg.com

South America

Ieda Novais

T: +551121833185

E: inov[email protected]

South Asia

Narayanan Ramaswamy

T: +91 443 914 5200

E: naray[email protected]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Charles Appleton

T: +254 20 2806000

E: charlesappleton@kpmg.co.ke

United Nations Desk

Emad Bibawi

T: +1 212 954 2033

Western Europe

Marianne Fallon

T: +44 20 73114989

kpmg.com/socialmedia kpmg.com/app

The information contained herein is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual

or entity. Although we endeavor to provide accurate and timely information, there can be no guarantee that such information is

accurate as of the date it is received or that it will continue to be accurate in the future. No one should act on such information

without appropriate professional advice after a thorough examination of the particular situation.

© 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. Member firms of the KPMG network of

independent firms are affiliated with KPMG International. KPMG International provides no client services. No member firm has any

authority to obligate or bind KPMG International or any other member firm vis-à-vis third parties, nor does KPMG International have

any such authority to obligate or bind any member firm. All rights reserved.

The KPMG name, logo and “cutting through complexity” are registered trademarks or trademarks of KPMG International.

Designed by Evalueserve.

Publication name: Monitoring and Evaluation in the Development Sector

Publication number: 131584

Publication date: September 2014