Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies

The Future of Oregon’s

Nursing Workforce:

Analysis and

Recommendations

Final Report

October 18, 2022

Timothy Bates, Emily Shen, & Joanne Spetz, University of California, San Francisco

Jana Bitton & Rick Allgeyer, Oregon Center for Nursing

Acknowledgements:

This report benefitted from the support and guidance of Marc Overbeck, Director of the Primary Care

Office, and Neelam Gupta, Director of Clinical Supports, Integration, and Workforce, at the Oregon

Health Authority.

We appreciate the input of the project’s Advisory Group, chartered by the Oregon Health Care

Workforce Committee: Patricia Barfield (Oregon Health & Science University), Susan Burke

(PeaceHealth), Matthew Calzia (Oregon Nurses Association), April Diaz (Marquis Companies), Andi

Easton (Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems), Ruby Jason (Oregon State Board of

Nursing), Paula Love (Avamere), Becky McCay (Oregon Health & Sciences University), Desi McCue

(Providence Health and Services), Jane Morrow (Central Oregon Community College Nursing

Program), Jane Palmieri (Portland Community College Nursing Program), Cathy Reynolds (Legacy

Health), Tina Ronczyk (PeaceHealth), Melody Routley (Kaiser Permanente), Casey Shillam (University

of Portland), and Jackie F. Webb (Oregon Health & Science University).

The Oregon Health Care Workforce Committee provided support and comments throughout our

research. We are particularly appreciative of Troy Larkin (Providence Health and Services), as well as

Chair Laura McKeane (AllCare Coordinated Care Organization), Vice-Chair Paul Gorman (Oregon

Health & Sciences University), and Immediate Past Chair Curt Stilp (George Fox University), for their

engagement in the Advisory Group and frequent feedback.

Representative Rachel Prusak sponsored the legislation that made this report possible. Her support

and feedback are greatly appreciated.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

2

Table of Contents

List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................................4

List of Figures ...........................................................................................................................................................5

Project Purpose ........................................................................................................................................................7

Nursing Practice in Oregon and the Nation ...........................................................................................................8

What is Nursing? ........................................................................................................................................................8

Nurse License Types and Specialties ........................................................................................................................8

Licensing and Regulation of Nurses ........................................................................................................................ 10

The Role of the Oregon State Board of Nursing ..................................................................................................... 12

Emergency Authorization Licensure 2020-2022 ........................................................................... 13

Perceptions of OSBN among key informants ................................................................................ 14

Solutions to OSBN Licensing Delays ............................................................................................ 15

Overview of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce .......................................................................................................... 15

Size and Demographics .......................................................................................................................................... 15

Number of Nursing Professionals in Oregon ................................................................................. 15

Age Distribution of Oregon Nurses ................................................................................................ 16

Gender of Oregon nurses .............................................................................................................. 17

Racial and ethnic diversity of Oregon nurses ................................................................................ 17

Languages spoken by Oregon nurses .......................................................................................... 18

Education and Training of nurses in Oregon ........................................................................................................... 19

Quality of Oregon’s nursing education programs .......................................................................... 23

Highest Educational Attainment of Oregon RNs ........................................................................... 25

Inter-state migration of nurses ................................................................................................................................. 29

International recruitment and immigration ............................................................................................................... 30

Patterns of Nurse Employment ................................................................................................................................ 31

Compensation of nurses .......................................................................................................................................... 31

Current Challenges for the Nursing Workforce .................................................................................................. 36

The national context ................................................................................................................................................ 36

Nursing shortages .................................................................................................................................................... 37

Ramifications of nursing shortages on organization operations and new graduate onboarding .. 38

Nurse vacancies ............................................................................................................................ 38

Retention of Nurses in Oregon ...................................................................................................... 39

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

3

Nurse workloads ...................................................................................................................................................... 42

The importance of nurse workload ................................................................................................ 42

Nurse workload in Oregon ............................................................................................................. 43

Responses to deal with increased workload ................................................................................. 44

Regulatory approaches to manage nurse workloads .................................................................... 44

Oregon’s 2015 Nurse Staffing Law ............................................................................................... 46

Nurse burnout .......................................................................................................................................................... 48

National estimates of nurse burnout .............................................................................................. 48

Factors contributing to nurse burnout ............................................................................................ 48

Effect of Nurse Burnout on Patient and Organizational Outcomes ............................................... 49

Evidence for mitigating burnout ..................................................................................................... 49

Oregon Center for Nursing’s Survey on Nurse Burnout ................................................................ 50

Nursing education capacity in Oregon..................................................................................................................... 58

Faculty shortages .......................................................................................................................... 58

Lack of Clinical Placements ........................................................................................................... 59

Transition into Practice for New Nurse Graduates .................................................................................................. 60

Strategies to address transition-to-practice challenges ................................................................ 61

Challenges with the LPN and CNA workforce ......................................................................................................... 63

Solutions Implemented and Considered in Oregon ........................................................................................... 64

Oregon Wellness Program ............................................................................................................ 64

Temporary Licensure ..................................................................................................................... 65

Nurse Intern Licensure .................................................................................................................. 65

Nurse Licensure Compact ............................................................................................................. 65

Conclusions and Recommendations .................................................................................................................. 68

Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................................. 68

Recommendations ................................................................................................................................................... 69

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

4

List of Tables

Table 1. License types and current numbers, 2022. ............................................................................. 13

Table 2. Applications and licenses issued, Jan. - Aug. 2022. ............................................................... 14

Table 3. Numbers of licensed and certified nurses in Oregon. ............................................................. 16

Table 4. Racial/ethnic distribution of Oregon nurses by license type. ................................................... 18

Table 5. Languages spoken by license type. ....................................................................................... 18

Table 6. Programs offered by Oregon's RN and LPN education programs. ......................................... 20

Table 7. Total student enrollment in practical nursing programs. ......................................................... 22

Table 8. Highest educational attainment of Oregon RNs, 2014-2020. .................................................. 25

Table 9. Enrollment and graduation by race/ethnicity in Oregon's RN programs over time. ................. 26

Table 10. Race/ethnicity of practical nursing students.......................................................................... 26

Table 11. Age of practical nursing students and graduates. ................................................................. 27

Table 12. Detailed description of employment settings used in the NSSRN, 2018. .............................. 34

Table 13. Median hourly wage by region and occupation, 2022. .......................................................... 35

Table 14. Hospital vacancies in Oregon and other states, 2019. .......................................................... 38

Table 15. Hospital full-time equivalent employment per 1000 adjusted patient days, 2019. ................. 43

Table 16. Nurse Well-Being Mental Health Survey respondents. ......................................................... 51

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

5

List of Figures

Figure 1. Age cohort by license type. ................................................................................................... 16

Figure 2. Age distribution for Oregon registered nurses, 2012 vs. 2020. .............................................. 17

Figure 3. Gender distribution of Oregon nurses by license type. .......................................................... 17

Figure 4. Locations of Oregon's RN and LPN education programs. ..................................................... 19

Figure 5. Total enrollment in Oregon's RN programs. .......................................................................... 21

Figure 6. New enrollments in Oregon's RN programs. ......................................................................... 21

Figure 7. Numbers of qualified applicants to Oregon RN education programs. .................................... 22

Figure 8. Registered nurse graduates over time. ................................................................................. 23

Figure 10. NCLEX-RN first time pass rate, Oregon vs. U.S.................................................................. 23

Figure 11. Oregon's NCLEX-RN first time pass rate by program type. ................................................. 24

Figure 12. Graduates by age group in Oregon's RN programs............................................................. 27

Figure 9. Graduations from practical nursing programs. ....................................................................... 28

Figure 13. Number of RN licenses approved by year of licensure. ....................................................... 29

Figure 14. Percent of RNs practicing in Oregon by method of licensure. ............................................. 30

Figure 15. Practice settings of Oregon RNs. ........................................................................................ 31

Figure 16. Median income from all nursing employment by full-time/part-time status, Oregon vs. U.S.,

2018. ............................................................................................................................................ 32

Figure 17. Nursing practitioner median income from all nursing employment by full-time/part-time

status, Oregon vs. U.S., 2018. ...................................................................................................... 32

Figure 18. Full-time median income from all nursing employment, by highest level of education,

Oregon, 2018................................................................................................................................ 33

Figure 19. Full-time median income from all nursing employment, by nursing experience, Oregon, 2018.

..................................................................................................................................................... 33

Figure 20. Annual median income from all nursing employment earned by full-time RNs, by

employment setting, 2018. ............................................................................................................ 34

Figure 21. Percentage of RNs employed who were also employed in nursing one year before, Oregon

vs United States, 2018. ................................................................................................................. 40

Figure 22. Change in Nursing Employment Location from Prior Year, Oregon vs United States, 2018. 40

Figure 23. Change in nursing position and employer from prior year, Oregon vs. U.S., 2018............... 41

Figure 24. Change in nursing employment status from prior year, Oregon vs. U.S., 2018. .................. 41

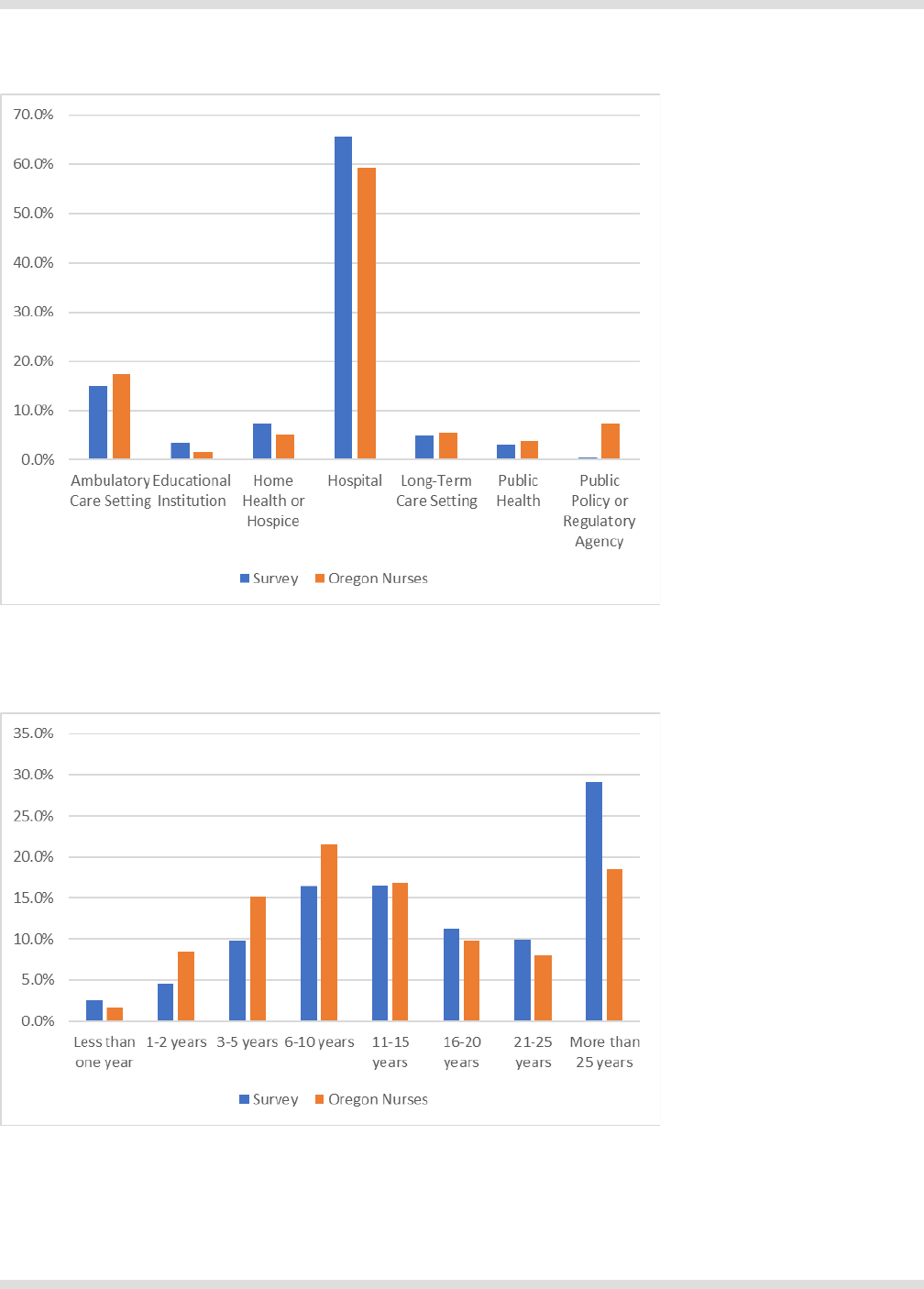

Figure 25. Age of RN Well-Being Mental Health Survey respondents. ................................................. 51

Figure 26. Work settings of RN Well-Being Mental Health Survey respondents. .................................. 52

Figure 27. Years of experience of RN Well-Being Mental Health Survey respondents ......................... 52

Figure 28. Feelings regularly experienced at work. .............................................................................. 53

Figure 29. Top five workplace stressors. .............................................................................................. 53

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

6

Figure 30. Symptoms experienced recently by respondents. ............................................................... 54

Figure 31. Do nurses receive adequate emotional support at work? .................................................... 55

Figure 32. Do nurses receive adequate emotional support at home? ................................................... 55

Figure 33. Changes in work environment nurses say they need. ......................................................... 56

Figure 34. Changes in work environment nurses say they want. .......................................................... 56

Figure 35. Number of faculty at Oregon’s RN programs. ...................................................................... 59

Figure 36. Known nurse residency programs in Oregon. ..................................................................... 63

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

7

Project Purpose

The Oregon Health Care Workforce Committee was directed by the Oregon Legislature (HB 4003) to

conduct a study of Oregon’s nursing workforce to identify and describe challenges in addressing

staffing shortages in nursing. This study is intended to provide information to inform the legislature and

Oregon Health Authority (OHA) in their efforts to address critical concerns about nursing workforce

shortages. The study considered all levels of care, including, but not limited to, hospitals, long-term

care facilities, community health centers, home health, public health, and schools.

The specific topics which interested the legislature and committee included:

• size and characteristics of the Oregon nursing workforce;

• administrative capacity of the Oregon State Board of Nursing (OSBN) to process licenses and

renewals, monitor disciplinary actions, and track the workforce, and related regulatory issues, such

as reciprocity with other states and the Nurse Licensure Compact (Compact);

• training capacity in Oregon, including availability of clinical placements;

• transition of newly graduated nurses into practice, including the workload impact to incumbent nurses

of onboarding newly graduated nurses;

• compensation of nurses, including both wages and benefits, across employment settings and nurse

experience;

• workload of nurses, including variation across settings, the use of unlicensed assistive personnel,

and the impact of skill mix;

• nurse burnout, retention, and vacancies across employment settings, age groups, and experience

levels;

• concerns about current and potential nursing shortages;

• inter-state migration of nurses;

• international recruitment and immigration; and

• the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the nursing workforce.

The cultural responsiveness of the nursing workforce is a foundational concern of the legislature and

Health Care Workforce Committee. In this context, cultural responsiveness describes the capacity of

the nursing workforce and of individual nurses to respond to the issues of diverse communities. The

cultural responsiveness of the workforce and of individual nurses aims to assure competent language

access and incorporation of diverse cultural approaches, strengths, perspectives, experiences, frames

of reference, values, norms and performance styles of clients and communities to make services and

programs more welcoming, accessible, appropriate and effective for all intended recipients. The domain

of cultural responsiveness was interwoven with each of the specific topics to ensure this foundational

domain was considered in every aspect of this work.

Our research team undertook a number of activities for this study. We began with reviews of the

national literature on nurse staffing, burnout, workloads, and the impact of COVID-19. We also

examined the literature on nurse transition-to-practice and education. We analyzed license and

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

8

education data from OSBN, licensing survey data from the Health Care Reporting Program, and nurse

well-being survey data from the Oregon Center for Nursing (OCN). We also analyzed data from the

U.S. American Community Survey, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the 2018 National Sample

Survey of Registered Nurses, the Oregon Employment Department, and the American Hospital

Association. Finally, we conducted interviews with leadership from OSBN, the Oregon Nurses

Association (ONA), the Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems, the Oregon Health Care

Association, and the Northwest Organization of Nurse Leaders. We interviewed hospital chief nursing

officers and clinical education leaders from rural and urban hospitals, experts in long-term care and

ambulatory care, deans and directors of registered nurse (RN) and licensed practical nurse (LPN)

education programs, and staff nurses.

Nursing Practice in Oregon and the Nation

What is Nursing?

Nursing is the largest health profession in the world and in the United States, with more than 4.2 million

RNs,

1

640,000 employed LPNs,

2

and 1.3 million employed certified nursing assistants (CNAs).

3

Nursing practice involves providing holistic care that includes monitoring patients and assessing their

situation and status, administering treatments and medications, supporting basic needs such as

toileting and feeding, providing education to patients and their families, and collaborating with

interprofessional teams.

Nursing practice spans many care domains across the life span, including disease prevention, health

education, treatment, supporting people living with disabilities, care coordination, and end-of-life care.

Nurses work closely with patients and the public, bringing a scientific understanding of care processes

that gives them what the Institute of Medicine described as “a unique ability to act as partners with

other health professionals and to lead in the improvement and redesign of the health care system and

its many practice environments.”

4

Nurse License Types and Specialties

There are three distinct categories of nursing care providers in the United States, and within these there

are specialties and advanced providers.

Certified nursing assistants (CNA) provide basic care under the direction of licensed nurses. They

support activities of daily living such as bathing, dressing, mobilization, toileting, and eating. Federal

standards for certification require 75 hours of state-approved training, and many states have greater

training requirements. The most common employment settings of CNAs are nursing homes, home

health agencies, and hospitals.

1

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2022). Nursing Fact Sheet. https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-Information/fact-

sheets/nursing-fact-sheet.

2

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). May 2021 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates.

https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm

.

3

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). May 2021 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates.

https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm

.

4

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

9

Licensed practical nurses (LPNs), called licensed vocational nurses in California and Texas, are

licensed professionals who provide basic nursing care including monitoring vital signs, administering

medications, and performing other tasks such as dressing changes and basic management of

intravenous lines. LPNs complete 12 to 18 months of education at a community college or

vocational/technical school and pass a national certification exam (the NCLEX-PN). The most common

employment settings of LPNs are home health, nursing homes, physician offices, and hospitals.

Registered nurses (RNs) provide essential nursing services including patient assessment and

monitoring, administering treatments and medications, educating patients and family members, and

coordinating care. According to ORS 678.010 (8)(a), the practice of nursing in Oregon means

“diagnosing and treating human responses to actual or potential health problems through services such

as identification thereof, health teaching, health counseling and providing care supportive to or

restorative of life and well-being and including the performance of additional services requiring

education and training that are recognized by the nursing profession as proper to be performed by

nurses licensed under ORS 678.010 (Definitions for ORS 678.010 to 678.410) to 678.410 (Fees) and

that are recognized by rules of the board.” Registered nurses complete an education program at a

community college, diploma school of nursing, or university, and pass a national licensing exam

(NCLEX-RN). Some schools offer programs specifically designed for LPNs to easily move into RN-level

education and licensure. RNs are the most numerous of the nursing occupations and many people use

the term “nurses” to refer specifically to RNs. The most common employment setting of RNs is

hospitals, but RNs can be found in every setting where health care and public health services are

provided.

Many RNs work in health care specialties, including critical care, public health, home health,

emergency and urgent care, occupational health, oncology, mental health, palliative care, and

perioperative care. Many of these specialties have their own certifications associated with some

combination of formal education, on-the-job experience, and examination. Some RNs obtain master’s

degrees to support their knowledge in these specialties, as well as in nursing administration, education,

and leadership.

Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) are RNs who have completed a master’s degree in

nursing (MSN) or doctor of nursing practice (DNP) in one of four categories:

• Nurse practitioners (NPs) are the most numerous of the APRNs and can specialize in primary care,

specialty care, acute care, and/or psychiatric-mental health care. They take health histories and

provide complete physical examinations, interpret laboratory results and other tests, diagnose and

treat common acute and chronic problems, and provide counseling and education. They refer

patients to other health care professionals when needed.

• Nurse midwives (NMs) provide reproductive and primary care, including management of low-risk

labor and delivery and neonatal care. If they are nationally certified, they are called certified nurse

midwives (CNMs).

• Nurse anesthetists (NAs) administer anesthesia including during surgery, obstetrical procedures,

and for pain management. They provide more than 65 percent of all anesthetics to patients in the

U.S.

4

If they are nationally certified, they are called certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs).

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

10

• Clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) are trained in a specialty area and practice in a variety of fields

and specialties including adult health, community health, geriatrics, school health, psychiatric-mental

health, and women’s health.

Licensing and Regulation of Nurses

Occupational licensure is the legal structure through which governments establish the qualifications

required to work in a profession. Only individuals with licenses are allowed to work in that occupation.

The intention of occupational licensure is to protect consumers by ensuring that professionals and

tradespeople are qualified for the services they provide.

5

For most occupations, licensure is regulated

by state governments.

6

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports 21.3 percent of the civilian labor

force held an occupational license in 2021.

7

Another component of occupational regulation is scope-of-practice regulation. This type of regulation

specifies the types of services and tasks that people in a licensed occupation are allowed to perform.

Scope-of-practice regulations are common among health care occupations and, like licensing

regulations, are generally considered to be the purview of states.

8

There are no federal standards or requirements for nurses to practice. States are expected to define

what constitutes competent and safe practice for nurses who treat their residents. Therefore, it is the

responsibility of each state to set the regulations for nurses and nursing practice.

Nurse regulation in Oregon

In Oregon, regulations related to nurse licensure and practice are defined in the Oregon Nurse Practice

Act, which contains both laws set by the legislature [Oregon Revised Statutes, Chapter 678.010-

678.445] and rules established by the Oregon State Board of Nursing (OSBN) [Oregon Administrative

Rules, Chapter 851].

The Nurse Practice Act sets standards for all aspects of nursing including:

• rules of practice and procedure;

• agency fees;

• nurse certification and licensing;

• scope-of-practice for nursing at all levels (CNAs, LPNs, RNs, and APRNs); and

• approval and standards for nursing education programs.

As is the case in most states, Oregon’s legislature has established broad requirements for nursing

regulation, and the details of regulation are left to the OSBN to determine. This structure supports the

5

Kleiner, M. M., & Vorotnikov, E. (2017). Analyzing occupational licensing among the states. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 52(2), 132-

158.

6

Kleiner, M. M., Marier, A., Park, K. W., & Wing, C. (2016). Relaxing occupational licensing requirements: Analyzing wages and prices for a

medical service. The Journal of Law and Economics, 59(2), 261-291.

7

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Statistics from Current Population Survey: Certification and licensing status of the civilian

noninstitutional population 16 years and over by employment status, 2021 annual averages. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat49.htm

.

8

Gilman, D. J., & Fairman, J. (2014). Antitrust and the future of nursing: Federal competition policy and the scope of practice. Health Matrix,

24, 143.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

11

evolution of policies to meet current needs and address emergent issues because it is easier to amend

regulations than laws.

Licensure and certification in Oregon

Nurse licensing requirements in Oregon are similar to those of other states and generally aligned with

the national Nurse Licensure Compact, which is a set of regulatory recommendations developed by the

National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN). The only substantive difference between

Oregon’s requirements and the Compact requirements is that Oregon allows people who have a prior

felony conviction to apply for licensure as an RN or LPN whereas the Compact does not. The OSBN

reviews prior arrests and convictions and makes determinations on an individual basis.

9

Oregon’s standards for CNAs differ from federal minimum training requirements. The federal standard

is 75 hours of training, of which 16 must be clinical. Oregon requires 155 hours of training. However, a

CNA who is certified by another state can apply to be a CNA in Oregon without completing additional

training even if the other state’s requirements are less than 155 hours. Oregon also has multiple levels

of certification for nursing assistants: CNA 1, CNA2, and certified medication assistant (CMA). To

become a CNA2, a CNA1 must have 75 hours of work experience as a CNA1 or a combination of work

and clinical training that adds to 75 hours, complete additional training in an OSBN-approved program,

and pass that program’s competency evaluation (Oregon Administrative Rules 851-062-0052). To

quality for CMA certification, a CNA can complete an OSBN-approved medication aide training program

and pass an examination. A student in a licensed nursing education program also can qualify as a

CMA, as can military corpsmen or medics and graduations of medication aide programs in other states.

Scope of practice in Oregon

RNs’ scope of practice does not vary substantially across states and Oregon’s scope of practice for

RNs is aligned with nationally accepted standards. In contrast, there is notable variation in LPN scope

of practice across states. Oregon’s scope-of-practice regulations for LPNs provide general guidance

that they must practice in alignment with their training and skills, which affords their employers with

flexibility in the assignment of tasks to LPNs. For example, Oregon regulations allow LPNs to

administer intravenous therapy, at the discretion of their employer, whereas LPNs are not allowed to do

this in California.

NPs and NMs in Oregon have full practice authority, which means they can practice independently to

the fullest extent of their knowledge and training. Oregon’s NPs and NMs are not required to be

supervised by or collaborate with a physician at any time.

10,11

Many other states require that NPs

and/or NMs practice under physician oversight; Oregon is viewed as a leader in allowing their APRNs

to have full practice authority as recommended by the Institute of Medicine.

4

9

For more information, see https://www.oregon.gov/osbn/pages/criminal-history.aspx

10

Spetz, J. (2018). California’s Nurse Practitioners: How Scope of Practice Laws Impact Care. Oakland, CA: California Health Care

Foundation. Revised 2019, July.

11

Kwong, C., Brooks, M., Dau, K. Q., & Spetz, J. (2019). California’s Midwives: How Scope of Practice Laws Impact Care. Oakland, CA:

California Health Care Foundation.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

12

CNAs in Oregon have a scope of practice that is quite expansive and aligned with the majority of

states. Some states place more restrictions on CNAs. In Oregon, a CNA1 provides care as directed in

an individual’s plan of care, which is developed by a licensed nurse. The CNA1 may carry out tasks

associated with infection control and prevention, transporting people to a wheelchair or other

specialized chair, using lifts and other client handling devices, turning oxygen on and off, assisting with

eating and elimination, including administering enemas, assisting with personal care such as

shampooing, and a variety of tasks associated with technical skills such as changing a suction canister.

The CNA2 may perform the same functions as a CNA1 and can help clients navigate the acute care

system, obtain throat swabs and urine specimens, assist with human milk pumping and handling, add

fluid to established tube feedings, change tube feeding bags, use adaptive equipment such as braces

and splints, and perform a wider range of tasks that require technical skills.

All CNAs may administer over-the-counter suppositories, topical barrier skin creams/ointments, and

treatments for lice, but they are not allowed to administer any other medications. CNAs can administer

oral, eye, ear, nasal, rectal, and vaginal medications under the direction of a licensed nurse. CNAs also

may administer medications delivered by nebulizers and can administer PRN (as needed) medications.

The Role of the Oregon State Board of Nursing

OSBN’s mission is to protect the public by regulating nursing education, licensure, and practice. OSBN

is responsible for:

• interpreting the Nurse Practice Act;

• conducting rule-making activities for Nurse Practice Act statutes, including public engagement, rule-

writing, and rule implementation;

• evaluating and approve nursing education and nursing assistant training programs;

• issuing licenses and renewals;

• investigating complaints and take disciplinary action against licensees who violate the Nurse Practice

Act;

• maintaining the nursing assistant registry and administer competency evaluations for nursing

assistants; and

• providing testimony to the legislature and other organizations as needed.

12

OSBN is governed by a nine-person board representing a variety of geographic locations and

consisting of two public members, one nurse educator, one nurse administrator, two direct-care non-

supervisory nurses, one licensed practical nurse, one certified nursing assistant, and one nurse

practitioner. As a state agency, OSBN board meetings are open to the public and include public

comment, except in cases of disciplinary hearings and executive session.

As of September 2022, OSBN reported overseeing licenses for more than 113,000 individuals (see

Table 1).

12

Oregon State Board of Nursing. (2022). What We Do. https://www.oregon.gov/osbn/Pages/about-us.aspx.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

13

The licensing process at OSBN requires several steps in which staff must directly verify components of

the application, such as transcripts and criminal record checks. According to OSBN, applications can

get delayed whenever a process isn’t automated or is reliant on staff or applicant intervention. Nurse

license applications can be delayed when applicants delay requesting documents required to verify

information such as school transcripts or out-of-state licensing verification, or applicants fail to obtain

fingerprints for background checks in a timely manner. Sometimes, if an applicant abandons the

application without notifying OSBN, the application retains a “Still in Progress” status, requiring staff

follow-up. Also, staff absences or turnover can delay the licensing process.

Table 1. License types and current numbers, 2022.

License Type

Number of

Licensees

Registered Nurses 80,123

Licensed Practical Nurses 6,128

Nurse Practitioners 6,687

Clinical Nurse Specialists 143

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists 720

Nurse Emeritus 31

Certified Nursing Assistants 18,979

Certified Medication Aides 850

TOTAL LICENSES 113,661

Source: OSBN Presentation to House Interim Committee on Health Care, Sept. 2022

Emergency Authorization Licensure 2020-2022

The COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruption in the licensing process in Oregon and the entire

country. When Governor Kate Brown issued Executive Order 20-03, which declared an emergency due

to the COVID-19 pandemic, OSBN created a new licensure, “Emergency Authorization Licenses” (EAL,

under OAR 851-001-0145), which allowed health employers to rapidly hire nurses, especially travel

nurses, to respond to increased demand for services. OSBN issued more than 13,000 EALs for out-of-

state nurses to work in Oregon during the pandemic.

Because the EAL was created in response to the Emergency Declaration, the EAL was set to expire

when the Emergency Declaration was rescinded by the Governor on April 1, 2022. OSBN extended

EALs for 90 days to allow nurses to apply for an Oregon license. This caused an increased demand for

Oregon licenses in February and March 2022 for nurses who wished to continue practice after the EAL

expired. The increased demand for licensure led to delays in the processing of applications. After

OSBN extended the EALs, the rush of applications slowed, as seen in Table 2.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

14

Table 2. Applications and licenses issued, Jan. - Aug. 2022.

Jan

2022

Feb

2022

March

2022

April

2022

May

2022

June

2022

July

2022

Aug

2022

Total

RN Applications

Received

1,353

1,443 2,738 2,000 1,990 1,836 1,520 1,485 14,365

RN Applications

Issued

778 783 999 1,256 1,169 1,895 1,960 1,472 10,312

CNA

Applications

Received

418 559 649 432 506 652 642 641 4,499

CNA

Applications

Issued

258 356 366 201 208 331 341 259 2,320

Source: OSBN Presentation to House Committee on Health Care, Sept. 2022

Perceptions of OSBN among key informants

Some of those interviewed perceived the processing of nursing license endorsements in Oregon takes

longer than in other states. One interviewee compared the OSBN to the nursing board in Washington

state, giving an example that in Washington, even at the height of the pandemic, the state nursing

board was processing endorsement applications within seven days while the interviewee believed it

took three months or longer to begin processing the application in Oregon. One interviewee described

the entire process taking anywhere from six months to a year to complete. Another stated that

employers have had to delay new employee start dates because OSBN could not process license

applications in a timely manner, and temporary licenses that cover a period of 90 days would often

expire before applications were processed. The OSBN reported in an interview that their time to

process a new application has been reduced from three months to 38 days, and their goal is to process

applications in within two weeks. They also noted that some delays in licensing are due to applicants’

not submitting complete files; OSBN measures its productivity based on when the application is

reviewed from completeness and validity. If the file is complete and valid, licensure occurs almost

immediately.

Some interviewees referenced a “lack of trust” between health care employers and OSBN. The lack of

transparency in the licensing process and the lack of communication between applicants and OSBN

was cited by multiple interviewees as an ongoing source of frustration for both applicants and

employers. Some of those interviewed noted that OSBN does not have any representation from the

long-term care sector, which may lead to decisions that affect organizations and nurses in long-term

care not considering those interests adequately. Some of those interviewed perceive that OSBN lacks

the resources to provide needed technical assistance to both applicants and employers. However,

OSBN reported in our interview that they have enough staff to clear the backlog of applications and

return to normal processing times soon.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

15

Solutions to OSBN Licensing Delays

OSBN’s benchmark to processing license applications is between 10 and 14 days. Because of the

increase demand for licenses during the pandemic, the time to process an application is currently about

38 days, down from about 90 days earlier in 2022.

To further reduce the time to process licenses, verification requirements would need to be revisited,

such as criminal background checks, competency verification through testing requirements, and

disciplinary actions taken on nurse licenses from other states.

Overview of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

Size and Demographics

Number of Nursing Professionals in Oregon

During 2020, almost 90,000 nursing professionals held a license to practice in the state of Oregon. Of

these, an estimated 70,000 are considered currently practicing in Oregon. RNs and CNAs are the most

numerous licensed professions with 59,778 and 18,640 licensees, respectively.

In Oregon, nursing professionals renew their licenses every two years, and a demographic/workforce

survey is conducted during renewal to gather date of birth, race/ethnicity, language spoken, gender,

educational attainment, employment status, practice characteristics. The survey collected race/ethnicity

using federal Office of Management and Budget standards, although a 2022 revision of the survey

incorporates Oregon’s REALD categories. Because of the timing of the survey, little is known about the

employment setting of newly licensed nursing professionals who obtain their first licenses and do not

take the workforce survey. To understand the total supply of nursing professionals in Oregon and take

into consideration newly licensed professionals, OCN developed a method to estimate the number of

practicing licensees. The employment rate of licensees completing the survey is applied to the newly

licensed individuals (and those who did not complete the survey) to estimate the number of practicing

individuals shown below. As can be seen in Table 3, in 2020, approximately 87 percent of CNAs, 83

percent of LPNs, 75 percent of RNs, and 78 percent of APRNs were practicing in their profession. A

survey conducted by the NCSBN reported that 76.6 percent of RNs and 76.5 percent of LPNs

nationwide were employed in nursing in 2020.

13

13

Smiley, R. A., Ruttinger, C., Oliveira, C. M., Hudson, L. R., Allgeyer, R., Reneau, K. A., Silvestre, J. H., & Alexander, M. (2021). The 2020

National Nursing Workforce Survey. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 12(1), S1-S96.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

16

Table 3. Numbers of licensed and certified nurses in Oregon.

Certified Nursing

Assistants (CNA)

Licensed Practical

Nurses (LPN)

Registered

Nurses (RN)

Advanced Practice

Registered Nurses (APRN)

Licensed 18,640 5,644 59,778 5,574

Practicing 16,200 4,680 44,900 4,330

Percent

Practicing

86.9% 82.9% 75.1% 77.7%

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020

Age Distribution of Oregon Nurses

Oregon nurses tend to be younger than in other states. The median age of an RN in Oregon is 51

years,

14

as compared to a median age of 52 for RNs nationwide.

13

The national sample shows the

largest cohort of RNs is over the age of 55. As seen in Figure 1, the largest age cohorts for CNAs,

LPNs, and RNs are 25-34 and 35-44, while the largest age cohorts for NPs are 35-44 and 45-55.

This trend of a younger nursing workforce has been developing for many years. In 2012, for example,

the largest age cohort of nurses was those between 55 and 60 years old (see Figure 2). Eight years

later, the largest age cohort is now between the ages of 30 and 35.

Figure 1. Age cohort by license type.

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020

14

Oregon Health Authority. (2020). Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File.

-4,000

1,000

6,000

11,000

16,000

<25 25-34 35-44 45-55 55-64 65+

CNA LPN RN NP

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

17

Figure 2. Age distribution for Oregon registered nurses, 2012 vs. 2020.

Source: OHA Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2012 and 2020

Gender of Oregon nurses

Currently, about 14 percent of licensed RNs in Oregon are male; nationally 9.4 percent of licensed RNs

are male.

13

Generally, the percent of male RNs and APRNs has grown over time. There are no data

with which the gender distribution of CNAs can be tracked over time.

Figure 3. Gender distribution of Oregon nurses by license type.

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020

Racial and ethnic diversity of Oregon nurses

Racial/ethnic minority groups are under-represented in Oregon’s nursing workforce compared to the

racial/ethnic makeup of the state’s population, although this representation is improving. In 2020, about

77 percent of licensed RNs identified as white, while 74 percent of the population of Oregonians

identified as white (see Table 4). In 2016, more than 88 percent of licensed RNs identified as white.

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

1,600

1,800

2,000

20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 91

No. Licensed RNs

2020

2012

11,787

4,138

42,727

3,546

2,032

568

6,278

513

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

CNA LPN RN NP

Male

Female

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

18

Hispanics are the most under-represented population, with only 3.9 percent of RNs identifying as

Hispanic, while almost 14 percent of the state’s population is Hispanic. Asians and Native

Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders are slightly over-represented (4.0% vs. 3.6%, 0.4% vs. 0.3%, respectively).

CNAs have the most diversity, particularly among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx

populations.

Table 4. Racial/ethnic distribution of Oregon nurses by license type.

Race/Ethnicity/Gender CNA LPN RN NP State Pop.

American Indian/Alaska Native 0.9% 0.7% 0.5% 0.3% 1.9%

Asian 5.9% 4.1% 4.1% 3.7% 5.0%

Black/African American 5.9% 4.1% 1.4% 1.8% 2.3%

Hispanic/Latinx 14.7% 7.8% 3.9% 3.7% 14.0%

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 1.0% 0.6% 0.4% 0.3% 0.5%

White (Not Hispanic) 57.0% 68.3% 76.8% 79.3% 74.1%

Multi-Racial 3.5% 3.6% 2.5% 2.1% 4.2%

Other Race 0.5% 0.4% 0.4% 0.5% n/a

Source: OHA Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020; US Census, 2021. Note: Some nurses do not provide race/ethnicity data and

thus columns may not add to 100%.

Languages spoken by Oregon nurses

Most of Oregon’s nursing workforce speak only English (see Table 5). Spanish is the second most

common language spoken by Oregon nurses, with 6.8 percent of RNs speak Spanish. Spanish was the

most common language spoken, other than English, for CNAs (13.7%), LPNs (7.4%), and NPs (14.4%)

as well. Tagalog and Russian were spoken by about 1.3 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively, by RNs

practicing in Oregon.

Table 5. Languages spoken by license type.

Language spoken

CNA

LPN

RN

NP

English Only 71.5% 82.6% 84.6% 77.4%

American Sign Language 0.5% 0.4% 0.2% 0.0%

Cantonese 0.2% 0.1% 0.2% 0.2%

Korean 0.2% 0.2% 0.3% 0.4%

Mandarin 0.2% 0.2% 0.2% 0.5%

Romanian 0.7% 0.5% 0.5% 0.2%

Russian 1.3% 1.1% 0.8% 0.6%

Spanish 13.7% 7.4% 6.8% 14.4%

Tagalog 3.0% 2.0% 1.3% 0.7%

Vietnamese 0.7% 0.4% 0.7% 0.5%

Source: OHA Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020. Note: Only languages spoken by at least 100 nurses across license type are

included, thus columns may not add to 100%.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

19

Education and Training of nurses in Oregon

Figure 4 maps Oregon’s RN and LPN education programs. Table 6 lists the schools that offer licensed

nurse education and indicates the programs they offer.

Oregon has eight LPN and 17 RN ADN programs offered at community colleges, and six bachelors of

science in nursing (BSN) programs offered at universities. OHSU School of Nursing, the only publicly

funded BSN-level program in Oregon, has five campuses across the state. Three universities have

Accelerated BSN programs where students with other bachelor’s degrees can earn a BSN in a

shortened amount of time. Four universities offer graduate-level education. Only OHSU and the

University of Portland offer DNP or a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degrees in nursing.

Figure 4. Locations of Oregon's RN and LPN education programs.

Source: Oregon Center for Nursing, 2022

Five schools offer a pathway for students with an ADN to earn a BSN (RN-to-BSN). OHSU has

partnered with 11 community colleges to form the Oregon Consortium of Nursing Education (OCNE).

These schools use a shared curriculum taught on all campuses, which allows students to take the

same core nursing courses in the first two years of nursing school, regardless of where they attend.

Upon completion, students can then complete the ADN program or continue to a BSN program through

OHSU either in person or online. According to the OCNE website, 6,045 students graduated from the

OCNE curriculum since its inception in 2001 and, as of winter 2021, 1,210 ADN graduates completed

their BSN at OHSU.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

20

Table 6. Programs offered by Oregon's RN and LPN education programs.

Source: Oregon Center for Nursing, 2022

Licensed Nurse Program Enrollments and Graduations

The number of registered nursing education programs in Oregon has not changed for more than a

decade. However, the number of students enrolled in programs continues to climb, particularly for BSN

programs. As seen in Figure 5, Oregon enrolls more than twice the number of BSN students as ADN

students. Since 2014, BSN programs have increased enrollment by 42 percent while ADN programs

have decreased enrollment by 15 percent. Data on CNA training program enrollments and graduations

are not available.

Student interest in nursing school remains strong in Oregon. New enrollments in BSN programs have

been growing at a high rate, particularly since 2017 (see Figure 6). Part of the increase in BSN new

enrollments can be attributed to two factors: a new BSN program opening in the Portland area (Warner

Pacific University), and an increase in new student enrollment for another program (University of

Portland School of Nursing) in 2018.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

21

Figure 5. Total enrollment in Oregon's RN programs.

Source: OSBN, Nursing Program Annual Report, 2012-2021

Figure 6. New enrollments in Oregon's RN programs.

Source: OSBN, Nursing Program Annual Report, 2012-2021.

Note: The OSBN Nursing Program Annual Report did not collect data for new enrollments in 2020, but resumed this data collection in 2021.

Since there are only eight schools offering LPN courses, and the number of schools has not changed

markedly since 2012, LPN graduates tend to be a small cohort. As seen in Table 7, Oregon’s practical

nursing programs received about 780 applications per year and about 70 percent of applicants were

admitted. About 500 LPN students are enrolled in programs in total.

1,393

1,416

1,454

1,412

1,245

1,238

1,230

1,223

1,313

1,233

1,939

2,015

1,965

2,083

2,043

2,167

2,150

2,350

2,673

2,797

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

ADN Programs BSN Programs

746

799

795

771

664

635

673

659

712

847

848

897

898

867

840

1,083

1,166

1,209

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

ADN Programs BSN Programs

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

22

Table 7. Total student enrollment in practical nursing programs.

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

Enrolled

540

442

501

510

443

Admitted

569

548

538

528

509

Applications

Received

854

791

749

768

627

Acceptance Rate

67%

69%

72%

69%

70%

Source: OSBN, Nursing Program Annual Report, 2012 and 2020

Applications to Oregon’s nursing programs have been declining since a peak in the 2017-2018 school

year (Figure 7). The decrease in applications has been most noticeable in ADN programs. From 2018

to 2021, applications to BSN programs decreased by 12 percent, while applications to ADN programs

decreased by 22 percent.

Figure 7. Numbers of qualified applicants to Oregon RN education programs.

Source: OSBN, Nursing Program Annual Report, 2017-2021

Oregon has a growing number of RN graduates, particularly in BSN level education. As seen in Figure

8, the number of BSN graduates has almost quadrupled in the past 20 years. In contrast, ADN

graduates have remained at a stable level since 2005.

2852

3129

2721

2512

2410

4762

5178

5050

4578

4558

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

2016-2017 2017-2018 2018-2019 2019-2020 2020-2021

ADN Programs BSN Programs

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

23

Figure 8. Registered nurse graduates over time.

Source: OSBN Annual Surveys of Nursing Education Programs, 2022

Quality of Oregon’s nursing education programs

Oregon’s nursing education programs are exceptionally successful in ensuring their graduates pass

national board examinations and thus qualify for licensure. As seen in Figure 34, the percentage of

graduates who pass the NCLEX-RN the first time they take it is notably higher in Oregon than the

nation. Pass rates have declined somewhat over the past few years; decreases in 2020 and 2021 are

often attributed to the pandemic, which disrupted both nursing education and the examination process.

Figure 9. NCLEX-RN first time pass rate, Oregon vs. U.S.

Source: NCSBN, NCLEX Examination Statistics, 2017-2021

307

412

465

600

595

779

805

747

791

990

1164

387

497

568

594

622

605

591

613

583

565

619

694

909

1033

1194

1217

1384

1396

1360

1374

1555

1783

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

1800

2000

2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

BSN graduates ADN graduates Total graduates

89.5%

92.9%

91.5%

90.1%

86.2%

87.1%

88.3%

88.2%

86.6%

82.5%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Oregon

United States

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

24

First-time NCLEX-RN pass rates are similar for ADN and BSN program, as seen in Figure 35. Key

informants generally held the view that nursing education at the ADN provides a solid foundation for

entering nursing, Although, they also generally expressed a belief that ADN-educated nurses are more

“task oriented,” have less developed clinical reasoning skills, and are less confident in their clinical

judgement. It was emphasized by many interviewees that ADN-educated nurses are critical to the

nursing workforce in rural and frontier areas of Oregon.

Figure 10. Oregon's NCLEX-RN first time pass rate by program type.

Source: NCSBN, NCLEX Examination Statistics, 2017-2021

Several interviewees emphasized that ADN nursing education is overly focused on the provision of

acute care and recommended curricula incorporate a greater level of exposure to population health and

community-based care models. In contrast, key informants generally expressed the view that nursing

education at the BSN level was doing a good job of preparing new nurses for roles outside of acute

care, including in roles related to population health and community-based care – in particular care for

vulnerable populations. Several key informants noted that BSN programs are in the process of

transitioning away from a focus on specialty care areas and toward the “four spheres of care” model:

prevention/promotion of health and wellbeing, chronic disease care, regenerative (critical/trauma) care,

and hospice/palliative care.

In general, key informants felt pre-license nursing education at both degree levels should place a

greater emphasis on conceptual models and take less of a task-based approach. Curricula need to

emphasize foundational concepts to prepare students to be able to cope with care situations they have

not encountered before. There was also a perception among key informants that pre-license nursing

students are too infrequently exposed to care settings outside of acute care, and in particular they are

critically underexposed to long-term care. One key informant commented that the lack of clinical

exposure to long-term care, and the lack of emphasis on aging and geriatrics, simply reinforces a bias

against working in long-term care settings. Some organizations recognize this challenge. The Oregon

Health Care Association recently received approval to train all community nurses to become certified

geriatric nurses, and is working on developing mentorship opportunities and a support program to

improve recruitment of nurses to long-term care settings.

89.5%

93.2%

90.0%

90.9%

85.8%

89.5%

92.7%

92.8%

89.5%

86.4%

80%

82%

84%

86%

88%

90%

92%

94%

96%

98%

100%

2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

ADN Programs BSN Programs

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

25

Highest Educational Attainment of Oregon RNs

In the past two decades, national and state campaigns have emphasized the importance of higher

education for nurses. This message has resulted in an increase in the number nurses whose highest

educational level is a BSN or higher degree, and slight decline in the number of nurses with an ADN.

As seen in Table 8, the percentage of nurses with the highest level of education being a master’s

degree or higher has remained stable since 2014.

Table 8. Highest educational attainment of Oregon RNs, 2014-2020.

2014

2016

2018

2020

Less than ADN 5% 5% 5% 3%

ADN 43% 41% 37% 34%

BSN 45% 48% 51% 54%

Master’s or Higher 6% 6% 7% 7%

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data Files, 2014 - 2020

Demographics of Oregon’s Licensed Nursing Students

A diverse, representative workforce contributes to better health outcomes, satisfaction with health care,

and access to care.

15

However, there continue to be gaps between the representation of Black, Native

American, Hispanic/Latinx, and some Asian subgroups in health care occupations as compared with

the general population.

16

Development of a diverse nursing workforce begins with cultivating students

from diverse backgrounds to enter nursing education programs. The success of this endeavor is

dependent on the capacity of the K-12 education system to support the success of diverse students; a

full exploration of this within Oregon’s elementary and secondary schools was outside the scope of our

study. Nonetheless, attention must be paid to the pipeline of students through the educational system

before they matriculate to nursing education.

Recent graduates from Oregon RN programs are more diverse than nurses in the workforce. For

example, graduates from BSN programs only report about 67 percent white, and ADN graduates report

64 percent white, compared to 77 percent white in the general RN population. While the diversity

among ADN and BSN graduates are similar, more graduates from ADN programs report their race as

“Other/Unknown,” and more BSN graduates report their ethnicity as Asian.

For both enrollments and graduations, and for students in both ADN and BSN programs, the number of

students from Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, and Black/African American backgrounds were

mostly unchanged from 2012 to present (Table 9). Year over year, however, the number of nursing

students from Hispanic backgrounds continues to grow. This is good news given the disparity between

the number of nurses who identify as Hispanic (3.9%) compared to the general population (14%).

15

US Department of Health and Human Services Advisory Committee on Minority Health. (2011). Reflecting America’s Population:

Diversifying a Competent Health Care Workforce for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: HHS, Office of Minority Health.

16

Taylor, K. J., Ford, L., Allen, E. H., Mitchell, F., Eldridge, M., & Caraveo, C. A. (2022). Improving and Expanding Programs to Support a

Diverse Health Care Workforce: Recommendations for Policy and Practice. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

26

Table 9. Enrollment and graduation by race/ethnicity in Oregon's RN programs over time.

ADN Students

BSN Students

Enrolled Graduated Enrolled Graduated

2012

2018

2020

2012

2018

2020

2012

2018

2020

2012

2018

2020

Hispanic 4% 6% 11% 4% 5% 10% 7% 12% 14% 5% 10% 12%

Native American 2% 1% 2% 1% 1% 2% 1% 1% 0% 2% 2% 0%

Asian 4% 3% 5% 4% 2% 4% 7% 11% 13% 7% 8% 8%

Pacific Islander 2% 1% 2% 1% 1% 2% 1% 1% 2% 2% 1% 2%

Black 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1% 1%

White 73% 68% 68% 81% 68% 63% 77% 67% 61% 74% 69% 67%

More Than One

Race

0%

2%

3%

0%

2%

4%

0%

6%

7%

0%

6%

6%

Unknown

16%

18%

9%

7%

20%

13%

6%

3%

2%

9%

3%

3%

Source: OSBN, Nursing Program Annual Report, 2013, 2019, 2021

The racial/ethnic composition of LPN students is more diverse than that of all licensed LPNs.

Enrollment and graduate percentages for LPN students from almost all racial backgrounds grew

noticeably between 2012 and 2020, except for students from Native American or Pacific Islander

backgrounds (see Table 10). While the percentage of LPN students who identify as Native American

remained unchanged over eight years, students who identified as being from Pacific Islander

backgrounds decreased for both enrollments and graduations to less than one percent of LPN students

in Oregon. While the data suggest that practical nursing programs are becoming more diverse, some of

this change could be due to reporting issues, including a marked decrease in the percent of the

students reporting an unknown racial/ethnic identity since 2012.

Table 10. Race/ethnicity of practical nursing students.

Newly Enrolled Graduates

2012 2020 2012 2020

Hispanic 6% 7% 3% 9%

Native American 1% 1% 2% 2%

Asian 4% 7% 3% 8%

Pacific Islander 3% 0% 4% 0%

Black 1% 10% 1% 12%

White 61% 54% 62% 52%

More Than One Race 0% 3% 0% 3%

Unknown 24% 17% 25% 14%

Source: OSBN, Nursing Program Annual Report, 2012 and 2020

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

27

Most RN graduates are between the ages of 21 and 40 years, as seen in Figure 12. Following national

trends, nurses who graduate from BSN programs are younger than ADN graduates, with more than half

between the ages of 21 and 25. ADN programs have almost 60 percent of their graduates falling

between the ages of 26 and 40.

Figure 11. Graduates by age group in Oregon's RN programs.

Source: OSBN Nursing Program Annual Report, 2019

Students enrolled and graduating from LPN programs tend to be in their 20s. The age distribution of

LPN graduates continued this trend with 50 percent of 2012 graduates and 58 percent of 2018

graduates age 30 years‐of‐age or younger. Very few practical nursing students and graduates were

over the age of 50. Comparable data on age of LPN students was not collected in 2020.

Table 11. Age of practical nursing students and graduates.

Newly Enrolled

Graduates

2012 2018 2012 2018

>20 10% 3% 1% 2%

21-25 27% 32% 26% 29%

26-30 25% 25% 22% 28%

31-40 23% 26% 22% 28%

41-50 13% 11% 15% 12%

51-60 2% 3% 5% 3%

>60 0% 0% 1% 0%

Source: OSBN Nursing Program Annual Report, 2012 and 2020

1.8%

24.6%

28.4%

31.1%

12.0%

2.0%

0.2%

0.0%

53.3%

21.7%

19.5%

4.9%

0.6%

0.0%

0.0%

10.0%

20.0%

30.0%

40.0%

50.0%

60.0%

≤20 21-25 26-30 31-40 41-50 51-60 >60

ADN Programs BSN Programs

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

28

Licensed Practical Nurse Program Graduations

LPN graduations averaged 393 per year between 2012 and 2020. As presented in Figure 9, there was

a decrease in LPN graduations between 2012 and 2016, followed by an increase between 2016 and

2018. Since 2018, there has been a decrease in LPN graduations.

Figure 12. Graduations from practical nursing programs.

Source: OSBN Annual Surveys of Nursing Education Programs, 2012-2020

534

425

411

367

329

352

400

389

331

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

29

Inter-state migration of nurses

There are two pathways to nurse licensure conducted by OSBN. One is referred to as “licensed via

examination,” which describes RNs who were educated and passed the NCLEX in Oregon. The second

pathway applies to licensed RNs who are practicing in another state. In this process, called “licensed

via endorsement,” OSBN staff verify the applicant has an unencumbered license in another state, has

the required education, and has passed the NCLEX examination. Once these requirements are met,

the applicant can receive an Oregon’s nursing license.

The proportion of RNs licensed via endorsement increased to 60 percent of the workforce for RNs

licensed since 2010 (Figure 13). It appears that the marked growth increase began around this time,

although the reason for this is not known. The rate of growth in the number of licenses obtained via

endorsement shows little sign of abating.

Figure 13. Number of RN licenses approved by year of licensure.

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020

A survey of Oregon nurses licensed by endorsement suggested that about 30 percent of endorsing

nurses were currently practicing in Oregon and another 11 percent lived in Oregon while practicing in

another state, namely California, Idaho, and Washington.

17

Thus, about 40 percent of endorsing RNs

were available to practice in Oregon based on their state of residence. More recent data from the OHA

indicate that 35 percent of RNs licensed by endorsement were practicing in Oregon (Figure 14).

17

Oregon Center for Nursing, Survey of Endorsing Nurses, November 2017.

4064

1462

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

4500

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Endorsement

Examination

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

30

Figure 14. Percent of RNs practicing in Oregon by method of licensure.

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020

Studies by OCN have shown the nurses who obtain their license by endorsement and practice within

the state generally practice in Oregon’s small, rural communities, often in non-hospital settings. A

decrease in the number of nurses migrating from other states and practicing in Oregon would likely

impact small counties the most.

International recruitment and immigration

There is very little data about international recruitment and immigration of foreign-educated nurses.

According to the OHA Nursing Public Use File from 2020, 50 LPNs and 1,385 RNs identified

themselves as foreign educated, accounting for less than one percent of LPNs and only 2.3 percent of

RNs.

Foreign-educated nurses must complete an established re-entry program before they can be licensed

to work in Oregon. Oregon has two re-entry programs recognized by OSBN. One of these programs,

the Immigrant Nurse Credential (INC), is designed to help foreign-educated nurses pass the

requirements to become a registered nurse in Oregon.

There is no data about how many foreign-educated nurses have immigrated to Oregon. Between 2018

and 2020, the INC program graduated 30 participants, and currently have about 19 foreign-educated

nurses on a waitlist for the next cohort of the program.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

Endorsement Examination

Practicing in OR

Not Practicing in OR

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

31

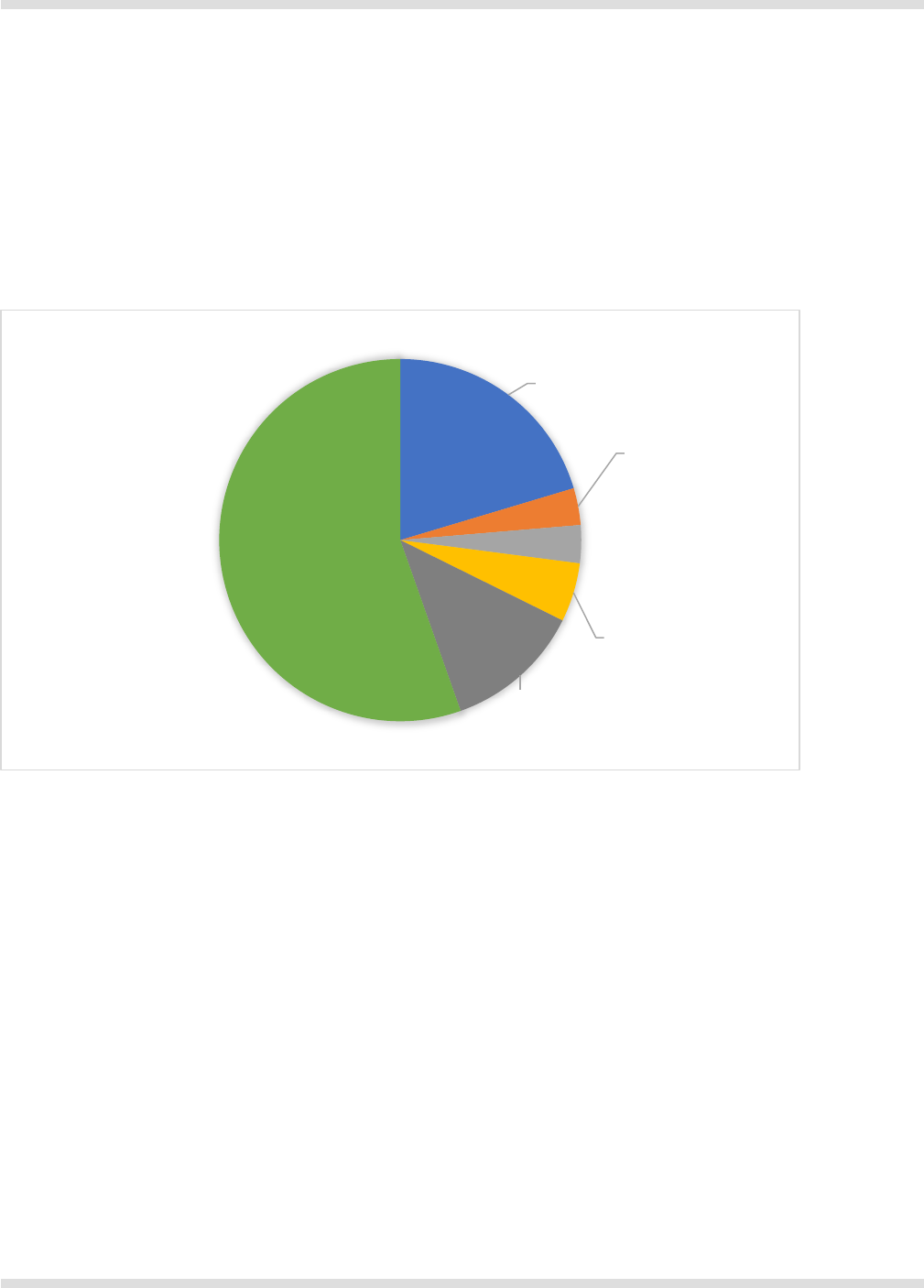

Patterns of Nurse Employment

As seen in Figure 15, the majority of Oregon’s licensed RNs practice in a hospital setting. In 2020, 55

percent of RNs worked in hospitals, which is the most common setting. Office/clinic settings was the

second most common setting, but only 12 percent of RNs reported practicing in this setting. National

data show similar findings. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 60 percent of RNs

worked in a hospital during 2020. The “Other Practice Setting” category includes nurses in public

health, K-12 education, policy, education, and regulation.

Figure 15. Practice settings of Oregon RNs.

Source: OHA, Public Use Nursing Workforce Data File, 2020

Compensation of nurses

Most of the data presented in this section are derived from the 2018 National Sample Survey

Registered Nurses (NSSRN). These data allow for analysis of the differences in RN compensation

associated with employment status, highest level of education, years of experience, and practice

setting. Figure 16 compares the 2018 median annual income for all nursing employment earned by

nurses employed in Oregon with the national average, for both full-time and part-time employment. The

median annual income for Oregon nurses who worked full-time was $14,000 (or 19%) greater than the

national average. Among those who reported part-time employment, the median annual income for

Oregon nurses was $23,000 (or 55%) greater than the national average.

Other Practice

Setting

20%

Ambulatory

Surgical Center

3%

Skilled Nursing

Facility/Long Term

Care

4%

Home

Health/Hospice

5%

Office/Clinic

12%

Hospital

56%

Future of Oregon’s Nursing Workforce

32

Figure 16. Median income from all nursing employment by full-time/part-time status, Oregon vs.

U.S., 2018.

Source: NSSRN, 2018

Note: U.S. median excludes Oregon. Data includes all nurses regardless of employment setting or advanced practice status.

Figure 17 replicates the comparison shown in Figure 16, but the data are limited to those employed as

a NP. In 2018, the median annual income earned by full-time NPs in Oregon was $12,000 (or 11%)

greater than the national average. Among those employed part-time, the difference in median annual

income was much smaller: part-time NPs in Oregon earned just $3,800 (or 6%) more.

Figure 17. Nursing practitioner median income from all nursing employment by full-time/part-

time status, Oregon vs. U.S., 2018.

Source: NSSRN, 2018

Note: U.S. median excludes Oregon.

Figure 18 compares the 2018 median annual income from all nursing employment earned by full-time

nurses in Oregon, based on their highest level of education in any field. These data show additional

education correlates with higher earnings. Nurses with a bachelor’s degree earned, on average, $9,000

$89,000

$65,000

$75,000

$42,000

$0

$20,000

$40,000

$60,000

$80,000

$100,000

Full-time Part-time