Giant Hogweed (Heracleum

mantegazzianum) - Poisonous

Invader of the Northeast

NYSG Invasive Species Factsheet Series: 07-1

Charles R. O’Neill, Jr.

Invasive Species Specialist

New York Sea Grant

February 2007, Revised August 2009

New York’s Sea Grant

Extension Program

provides Equal Program

and Equal Employment

Opportunities in associa-

tion with Cornell Coop-

erative Extension, U.S.

Department of Agriculture

and U.S. Department of

Commerce, and cooperat-

ing County Cooperative

Extension Associations.

New York Sea Grant

SUNY College at

Brockport

Brockport, NY 14420

Tel: (585) 395-2638

Fax: (585) 395-2466

Heracleum mantegazzianum

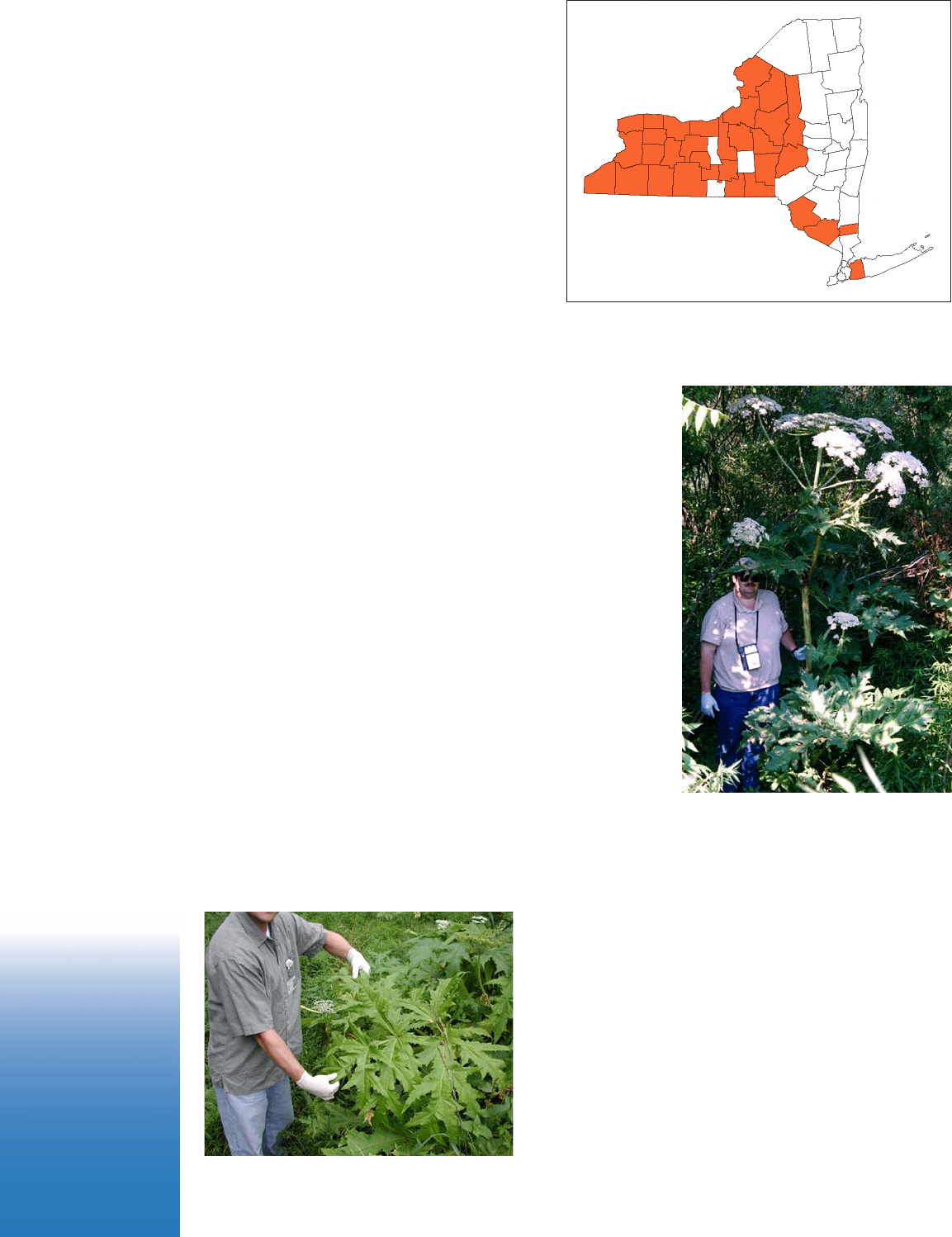

Should you be walking along a damp abandoned railroad right-of-way, a wet

roadside ditch or a stream bank and stumble upon a plant that looks like Queen

Anne’s Lace with an attitude – more than 10 feet tall with two-inch thick stems,

owers two or more feet across and leaf clusters as wide as you can stretch your

arms – stay clear! You have just

become one of an increasing

number of New Yorkers who

have met the state’s most striking,

and dangerous, invasive plant,

the giant hogweed (Heracleum

mantegazzianum) and you

absolutely do not want to touch

it and take it home to the family.

Giant hogweed can make a case of

poison ivy seem like a mild itch.

Photo: Randy Westbrooks, USGS

Introduction

History and Distribution

A member of the carrot and parsley family of plants (Apiaceae), giant hogweed is

native to the Caucasus region of Eurasia. Because of its unique size and impressive

ower head, the plant was originally introduced to Great Britain as an ornamental

curiosity in the 19th century. The plant is named after the mythological god,

Hercules (he of robust size and strength). It was later transported to the United

States and Canada as a showpiece in arboreta and Victorian gardens (one of the

plant’s rst North American plantings of giant hogweed was in gardens near

Highland Park in the City of Rochester, New York). It was also a favorite of

beekeepers because of the size its ower heads (the amount of food for bees is

substantial). A powder made from the dried seeds is also used as a spice in Iranian

cooking. Unfortunately, as with so many invasive plants, giant hogweed escaped

cultivation and has now become naturalized in a number of areas, including:

Broome, Cattaraugus, Cayuga, Chautauqua, Erie, Genesee, Herkimer, Jefferson,

Lewis, Livingston, Madison, Monroe, Nassau, Niagara, Oneida, Onondaga,

Ontario, Orange, Orleans, Oswego, Putnam, Schuyler, Steuben, Sullivan, Tioga,

Tompkins, Wayne, Wyoming, and Yates Counties in New York; Connecticut; the

Giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) is a member of the carrot or parsley family, Apiaceae

(Umbelliferae). Except for its size, the plant can be mistaken for a number of native, noninvasive

plants such as cow parsnip (Heracleum lanatum), Angelica

(Angelica atropurpurea), and poison hemlock (Conium

maculatum). Of these, the plant most likely to be misidentied

as giant hogweed is cow parsnip. A fourth, not so innocuous,

invasive giant hogweed imposter found throughout North

America is wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa). Information on how

to distinguish these giant hogweed wannabees from the real

thing can be found later in this factsheet.

Giant hogweed is a perennial herb with tuberous root stalks.

It survives from one growing season to another by forming

perennating buds (surviving from season to season) and

enduring a period of dormancy during the winter. The plant

develops numerous white owers that form a at-topped,

umbrella-shaped head up to two and a half feet across,

resembling “Queen Anne’s Lace on steroids.” Flowers form

from late-spring through mid-summer. Numerous (up to

100,000), half inch long, winged, attened oval seeds form in

late-summer. These seeds, originally green, turn brown as they

dry and can be spread by animals, surface runoff of rain, or on the wind, establishing new colonies.

Seeds can remain viable in the soil for up to 10 years. The plant’s stems die in the fall and remain

standing through the winter, topped with the huge, brown dead ower heads.

Giant hogweed’s thick hollow stems are generally one to

three inches in diameter but can reach four inches. Also

impressive are the plant’s lobed, deeply incised compound

leaves, which can reach up to ve feet in width. The plant

may grow to 15 to 20 feet in height.

Giant hogweed can colonize a wide range of habitats but

prefers rich, damp soil such as that found along abandoned

railroad rights-of-way, roadside ditches, stream banks, or

other moist disturbed areas. Because of this predilection

for wet areas, the plant is considered to be an aquatic

invasive species.

2

Conrmed sightings - August 2009

District of Columbia; Illinois; Maine; Maryland;

Massachusetts; Michigan; Ohio; Oregon;

Pennsylvania; Washington; Wisconsin; and the

Canadian Provinces of British Columbia, New

Brunswick, Ontario and Quebec.

Because of its public health hazard potential

and, to a lesser extent, to its potential ecological

impacts, giant hogweed is on the federal

noxious weed list and several state lists of

prohibited plant species.

Biology and Habitat

Photo: Terry English, USDA APHIS PPQ

Giant hogweed leaves can be up to ve feet across.

Photo: Thomas B. Denholm, NJDA

3

IDENTIFICIDENTIFIC

IDENTIFICIDENTIFIC

IDENTIFIC

AA

AA

A

TIONTION

TIONTION

TION

As mentioned earlier, there are several plants in New York and the Northeast that can be mistaken for giant

hogweed. Key features for distinguishing these plants from giant hogweed are explained below.

Comparisson photographs can be found in tables on pages 4 and 5.

Giant hogwGiant hogw

Giant hogwGiant hogw

Giant hogw

eedeed

eedeed

eed may grow to 15 to 20 feet in height. Stems are 1 to 3 inches in diameter, but may reach 4

inches. Stems are marked with dark purplish blotches and raised nodules. Leaf stalks are spotted, hollow,

and covered with sturdy bristles (most prominent at the base of the stalk). Stems are also covered with

hairs but not as prominently as the leaf stalks. Leaves are compound, lobed, and deeply incised; can reach

up to 5 feet in width. Numerous white flowers form a flat-topped, umbrella-shaped head up to two and a

half feet across. [Photos, page 4]

Native

CoCo

CoCo

Co

w parw par

w parw par

w par

snipsnip

snipsnip

snip, while resembling giant hogweed, grows to only five to eight feet tall. The deeply

ridged stems can be green or slightly purple, do not exhibit the dark purplish blotches and raised nodules

of hogweed, and only reach one to two inches in diameter, contrasted with hogweed stems which can

reach three to four inches in diameter. Where giant hogweed has coarse bristly hairs on its stems and

stalks, cow parsnip is covered with finer hairs that give the plant a fuzzy appearance. Both sides of the

leaves exhibit these hairs but they are predominantly on the underside of the leaves. In contrast to

hogweed’s two to two and a half foot flower heads, cow parsnip flower clusters are less than a foot across.

The size difference carries over into leaf size with hogweed’s five foot, deeply incised leaves replaced by

leaves that are less incised and only two to two and a half foot across. [Photos, page 4]

Native

purpur

purpur

pur

ple-stple-st

ple-stple-st

ple-st

emmed Angelicaemmed Angelica

emmed Angelicaemmed Angelica

emmed Angelica is more easily differentiated from giant hogweed by its smooth, waxy

green to purple stems (no bristles, no nodules), and its softball-sized clusters of greenish-white or white

flowers, seldom reaching a foot across. As with cow parsnip, Angelica is much shorter than giant

hogweed, usually no more than eight feet tall. Angelica leaves are comprised of many small leaflets and

seldom reach more than two feet across. [Photos, page 4]

PP

PP

P

oison hemlocoison hemloc

oison hemlocoison hemloc

oison hemloc

kk

kk

k, a non-native biennial, is also shorter than giant hogweed, growing to only four to nine

feet in height. While the stem has some purple blotches, it is waxy and the entire plant (stems, stalks,

leaves) is smooth and hairless. The leaves are dramatically different from those of hogweed, being fern-

like and a bright, almost glossy, green. All branches have small flat-topped clusters of small white flowers.

Another distinguishing characteristic is poison hemlock’s unpleasant mouse-like odor. The entire plant is

toxic, and the volatile alkaloids can even be toxic when inhaled. [Photos, page 5]

Wild parWild par

Wild parWild par

Wild par

snipsnip

snipsnip

snip, like giant hogweed, is of special concern because it, too, can cause phytophotodermititis,

only not usually as severe as that of giant hogweed. This plant can be found extensively throughout NY’s

Southern Tier, in the region east of Lake Ontario, some Central and Western NY counties, parts of the

Catskills and counties east of the Hudson River. Unlike the perennial giant hogweed, wild parsnip is a

biennial, producing a rosette of leaves close to the ground in its first year and a single flower stalk with a

flat-topped umbel with clusters of yellow flowers in its second year. The plant reproduces by means of the

seeds of these flowers; it does not regrow from its root as does giant hogweed. Wild parsnip is much

smaller than giant hogweed, seldom exceeding 5-feet in height. Wild parsnip stems are yellowish-green

with verticle grooves running their length. Wild parsnip has compound pinnate leaves with 5 to 15 toothed

and variably lobed yellowish-green leaves. [Photos, page 5]

IMPIMP

IMPIMP

IMP

AA

AA

A

CTCT

CTCT

CT

SS

SS

S

Giant hogweed is one of a very few North American invasive plants that can cause human health impacts

as well as ecological damage.

4

DEEWGOHTNAIG

THGIEH

teef02ot51

METS

retemaidhcni3ot1

ffits,sehctolbelpruP

seltsirb

FAEL

,debol,dnuopmoC

otpu;desicniylpeed

ediwteef5

REWOLF

-talf,srewolfetihW

pu,allerbmu,deppot

ssorcateef5.2ot

PINSRAPWOC

THGIEH

teef8ot5

METS

retemaidhcni2ot1

neerg,degdirylpeeD

enif,elprupylthgilsot

yzzuf,sriah

FAEL

ssel,dnuopmoC

teef2/12ot2,desicni

sriahyzzuf,ssorca

REWOLF

sretsulcrewolfhsitihW

toof1nahtregralon

ssorca

ACILEGNA

THGIEH

teef9ot4

METS

neergyxaw,htoomS

,)seltsirbon(elprupot

hcni2/12ot1

retemaid

FAEL

,stelfaelllamsynaM

owtnahterommodles

ssorcateef

REWOLF

,sretsulcdezis-llabtfoS

roetihw-hsineerg

toof1otpu,etihw

ssorca

5

KCOLMEHNOSIOP

THGIEH

teef9ot4

METS

,sselriahdnahtoomS

emos,neergyxaw

ot1,sehctolpselprup

retemaidhcni2

FAEL

,thgirb,ekil-nreF

neerg,yssolgtsomla

REWOLF

evahsehcnarbllA

deppot-talfllams

etihwllamsfosretsulc

srewolf

PINSRAPDLIW

THGIEH

teef5otpU

METS

htiwneerg-hsiwolleY

sevoorgelcitrev

htgnelllufgninnur

FAEL

5,etannip,dnuopmoC

ylbairav,dehtoot51ot

neerg-hsiwolley,debol

REWOLF

klatsrewolfelgniS

lebmudeppot-talfhtiw

wolleyderetsulcfo

srewolf

Ecological ImpactsEcological Impacts

Ecological ImpactsEcological Impacts

Ecological Impacts

Colonies of giant hogweed can become quite dense owing to the plant’s prolific seed production and

rapid growth rate. Such dense stands crowd out slower growing plants, the thick hogweed canopy

displacing native plants that need direct sunlight to grow. The decreased abundance of beneficial native

plants can reduce the utility of the area for wildlife habitat. When riparian plants are displaced, stream

bank erosion can increase and streambeds can be covered with silt.

Human Health ImpactsHuman Health Impacts

Human Health ImpactsHuman Health Impacts

Human Health Impacts

Giant hogweed is one of a handful of plants in the Northeast that can cause a significant reaction when

humans come in direct contact with the plant. Spread of this plant in urban and suburban areas is viewed

as an incipient public health hazard. [Wild parsnip can result in almost as severe reactions.]

Soon after humans bruise the leaves or stems of the more common poison ivy, poison oak, and poison

sumac, an allergic reaction to the plants’ poisonous oil (akin to carbolic acid) causes significant skin

6

irritation, itching, rashes and open sores. In the case of giant hogweed, however, the skin inflammation

is not caused by simply brushing against the plant’s leaves or stems. For giant hogweed to affect a

person, sap from a broken stem or crushed leaf, root, flower or seed must come into contact with moist

skin (perspiration will suffice) with the skin then being exposed to sunlight. Irritation is not immediate,

but will usually appear within one to three days after exposure. This form of skin irritation (dermatitis)

is called “phytophotodermatitis”. The plant’s clear, watery sap contains a glucoside called

furanocoumarin that is a psoralen. Psoralens sensitize the skin to ultraviolet radiation and can result in

severe burns, blistering, painful sores, and purplish or blackened scars. These phototoxic effects are the

result of the binding of the psoralens to nuclear DNA under the influence of ultraviolet irradiation, and

the subsequent death of affected cells.

The first signs of giant hogweed-caused

photodermatitis are when the skin turns red and

starts itching. Within 24 hours, burn-like lesions

form, followed by large, fluid filled blisters

within 48 hours. The initial irritation usually will

subside within a few days, but affected areas may

remain hypersensitive to ultraviolet light for

many years and re-eruptions of lesions and

blisters may occur. On rare occasions,

particularly in very sensitive individuals, the

burns and blisters may be bad enough to require

hospitalization. A side effect of exposure to the psoralens is the production of excessive amounts of

melanin in the skin, resulting in residual brown blotches called hyper-pigmentation; scars and brown to

black blotches may last for several years. The worst risk of exposure to giant hogweed is to one's eyes -

getting even minute amounts of the sap in the eyes can result in ttemporary or even permanent

blindness. Medical help should be sought immediately; by the time symptoms of burning and

hypersensitivity to sunlight are apparent, the damage could already be irreversible.

The only known antidote to contact with the sap is to immediately wash skin thoroughly with soap and

water, removing the sap and hopefully preventing any reaction with subsequent exposure to sunlight.

Once the irritation begins, medical advice should be sought. Treatment with prescription topical

steroids early on may reduce the severity of a person’s reaction. It will also be important to cover the

burns and blisters with light sterile dressings to prevent infection. Long-term, use of sunblock in

subsequent years may be required to prevent sensitization by sunlight again.

People most at risk include landscape technicians and yard maintenance laborers who may come in

contact with the sap when cutting the plant down or using line trimmers to control new growth.

Children breaking off the long, bamboo-like stems to use as play swords are also at great risk.

However, sometimes direct contact with the plant is not necessary for a reaction. Farmers have been

known to develop symptoms when they touch cows who have gotten the sap on their skin while

grazing (cows, themselves, seem impervious to the sap). The best prevention measure is to wear long

sleeves and long-legged pants when contact with the plant is a possibility.

CONTRCONTR

CONTRCONTR

CONTR

OLOL

OLOL

OL

If it weren’t for giant hogweed’s public health impacts, the plant most likely would not be worth the

effort of controlling it. Although it does have ecologic impacts, they are not as severe as many other

wetland invasive plants. However, the health impacts can be severe and the plant has found itself on the

federal noxious weed list and several state lists, as well. It is a particular target of parks and transporta-

tion/highway departments’ invasive plant eradication efforts. Such eradication programs can incorpo-

rate a combination of physical removal and chemical control. If undertaken properly, such programs can

be done without harm to humans or damage to the environment. Recently some landowners have been

USDA APHIS PPQ

7

known to refuse permission to allow highway departments to chemically treat giant hogweed thickets. It is

believed that this is usually a case of lack of knowledge on the landowner’s part.

Giant hogweed is very difcult to eradicate. Although the stems, stalks, leaves and owers can be killed

with a number of common selective herbicides, such as 2,4-D (the third most-often used herbicide in

North America), dicamba (a benzoic acid herbicide), TBA (terbuthylazine) and MCPA, these herbicides

are not effective at killing the plant’s tuberous perennial roots. Another common, selective broadleaf

herbicide, triclopyr (a common brand name is Brush-B-Gone®), is also effective, particularly when

applied directly to the entire surface of leaves and stems during periods of active growth; numerous

applications may be needed to kill the root stalk. Cornell Cooperative Extension recommends early

application (during the bud stage and the period of active plant growth) of glyphosate (commonly sold

under the trade names Rodeo® and Roundup®). Care should be taken when using any herbicides to

control giant hogweed; particular care should be taken when using glyphosate as it is nonselective and

will kill both the hogweed and desirable plants such as grass.

For those hesitant to utilize herbicides, giant hogweed can be managed using various “cultural” methods.

Unfortunately, owing to the plant’s persistence and spread by blowing seeds, such control can take

many seasons worth of effort to achieve 100% control. Individual plants can be dug out, removing the

entire rootstalk, a difcult process, particularly in patches where the plant has spread by root growth.

Mowing, cutting and use of line trimmers can be used to remove a standing crop and starve the rootstalk.

Unfortunately, unless performed numerous times during a season, mowing only serves to stimulate

budding on the rootstalk. All of these methods should be done with extreme care and only while wearing

protective clothing and eye protection. Skin contact with soiled clothing should also be avoided.

Biocontrol by grazing cows and pigs (which are apparently not affected by the plant’s sap) may also

help to manage but not eliminate the plant. Care should be taken not to get sap on uncovered skin when

touching livestock after the animals contact crushed or bruised hogweed.

Control of wild parsnip is less difcult than controlling giant hogweed because as a biennial, wild parsnip

reproduces only from seed, not from its rootstock. This plant can be controlled by cutting the stem from

the root below ground level with a shovel, spade or machete before the seed head matures.

And If All of That Isn’t Strange Enough…

Very few invasive species get immortalized in song. Giant hogweed is an exception. In 1971, Genesis

released their album “Nursery Cryme” which includes the song “The Return of the Giant Hogweed.”

“Turn and run! Nothing can stop them,

Around every river and canal their power is growing.

Stamp them out! We must destroy them,

They inltrate each city with their thick dark warning odour.

Waste no time! They are approaching.

Hurry now, we must protect ourselves and nd some shelter

Strike by night! They are defenseless.

They all need the sun to photosensitize their venom.

They are invincible, They seem immune to all our herbicidal battering.”

If you nd giant hogweed in NYS, you are encouraged to call NYS DEC’s Giant Hogweed Hotline:

845-256-3111

Heracleum mantegazzianum

New York Sea Grant

SUNY College at

Brockport

Brockport, NY 14420

Tel: (585) 395-2638

Fax: (585) 395-2466

Produced by New York Sea Grant, February 2006

RR

RR

R

efef

efef

ef

erenceserences

erenceserences

erences

Anon. Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum). Written Findings of the State Noxious Weed

Control Board - Class A Weed. State of Washington. 4 pp.

Camm E, et al. 1976. Phytophotodermatitis from Heracleum mantegazzianum. Contact Dermatitis. 2,

68-72.

Davies DHK, Richards MC. 1985. Evaluation of herbicides for control of giant hogweed (Heracleum

mantegazzianum Somm & Lev.), and vegetation re-growth in treated areas. Tests of Agrochemicals and

Cultivars. Annals of Applied Biology. (6):100-101.

Genesis. 1971. The Return of the Giant Hogweed.

Hypio, P, Cope, E. 1982. Giant Hogweed, Heracleum mantegazzianum. Cornell Cooperative Exten-

sion. Misc. Bulletin 123.

Kees H, Krumrey G. 1983. Heracleum mantegazzianum - ornamental plant, weed and poisonous plant.

[toxicity to livestock and humans, control]. Gesunde Pflanzen. Kommentator.3 5(4):108-110.

Northall F. 2003. Vegetation, Vegetables, Vesicles: Plants and Skin. Emerg. Nurse. 11(3):18-23.

InfInf

InfInf

Inf

ormational Linksormational Links

ormational Linksormational Links

ormational Links

Giant Hogweed - Overview, Invasive Plant Council of New York State: http://www.ipcnys.org/

sections/target/giant_hogweed_overview.htm

Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum), Written Findings of the State Noxious Weed Control

Board - Class A Weed: http://www.nwcb.wa.gov/weed_info/Written_findings/

Heracleum_mantegazzianum.html

Potential Health Hazard, Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum). Allegany/Cattaraugus Home

Grounds & Gardens, Cornell Cooperative Extension: http://counties.cce.cornell.edu/

allegany_cattaraugus/hort/PestAlert.htm

PhoPho

PhoPho

Pho

tt

tt

t

ograph and Graphics Creditsograph and Graphics Credits

ograph and Graphics Creditsograph and Graphics Credits

ograph and Graphics Credits

Page 1: Randy Westbrooks, U.S. Geological Survey, www.forestryimages.org

Map, page 2: New York Sea Grant

Page 2, right: Terry English, USDA APHIS PPQ, www.forestryimages.org

Page 2, left: Thomas B. Denholm, New Jersey Department of Agriculture, www.forestryimages.org

Page 3: USDA APHIS PPQ, www.forestryimages.org

Giant Hogweed Table, left to right:

Terry English, USDA APHIS PPQ @ www.forestryimages.org

Cornell Cooperative Extension - Allegany/Cattaraugus Counties

Donna R. Ellis, University of Connecticut @ www.forestryimages.org

Terry English, USDA APHIS PPQ @ www.forestryimages.org

Cow Parsnip Table, left to right:

UMASS Extension @ http://www.umassgreeninfo.org/index.html

James Altland, Oregon State Univ. North Willamette Research & Extension Center

UMASS Extension @ http://www.umassgreeninfo.org/index.html

Dave Powell, USDA Forest Service @ www.forestryimages.org

Angelica Table, left to right:

Virginia Kline, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Dept. of Botany

Flora of the Northeast United States @ www.web.syr.edu

Flora of the Northeast United States @ www.web.syr.edu

Albert FW Vick Jr., Native Plant Information Network @ www.wildflower2.org

Poison Hemlock Table, left to right:

Dan Tenaglia @ www.missouriplants.com

Dan Tenaglia @ www.missouriplants.com

Patrick J. Alexander @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Brother Alfred Brousseau, St. Mary's College of CA @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

Wild Parsnip Table, left to right:

Linda Haugen, USDA Forest Service @ www.forestryimages.org

Dan Tenaglia @ www.missouriplants.com

Patrick J. Alexander @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database

UMASS Extension @ http://www.umassgreeninfo.org/index.html