149

Mass Communication

Portrayals of Older Adults

EIGHT

This chapter describes how older adults

are portrayed in various media. By the end

of this chapter you should be

able to:

• Describe the meaning of the term

“underrepresentation”

• Summarize the media

contexts in which older

people are underrepresented in the

media

• Describe the situations in

which older adults are

positively and negatively

represented in the media

• Talk about historical trends in

portrayals of older people

• Understand the media industry dynamics that might influence

portrayals of older adults

SOURCE: ©Gettyimages

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 149

[Seniors] do not see themselves portrayed and when then do, it’s in

a demeaning manner. They’re referred to as “over the hill,”“old

goats” and “old farts”—oh please, ugly ways of talking about us.

—Doris Roberts [Marie Barone on Everybody Loves Raymond],

Interview with the Parents Television Council, 2003

I

f we want to understand where a group stands in society, there are few

better ways of getting information than by watching television.If a group of

people is featured prominently on TV and is shown in a positive light, and the

main characters in most shows come from that group, you can probably safely

conclude that the group is valued by society and has power. Likewise, if you

don’t see a group,or they tend to be shown in peripheral or negative roles,you

can conclude that this group lacks clout. In social science terms, the group

lacks vitality.Vitality refers to a group’s strength, status,size, and influence in

a particular context. In the United States, white men as a group have the high-

est vitality (just look at the list of U.S.presidents:White men = 42,Others = 0).

So it is with age groups. Numerous scholars have examined different

media contexts, particularly television, with the goal of understanding how

and when age groups are shown, and thus drawing inferences about the rela-

tive power of different age groups in society. What they have found may not

surprise those of you who have read the earlier chapters in this book, or

indeed those of you who spend a lot of time watching television. In this

chapter, I describe some of these findings, focusing particularly on North

American and European media.Chapter 10 presents some cross-cultural data

on this issue.

Underrepresentation

One of the most common techniques for examining group portrayals on tele-

vision is simply to count the number of members of certain groups in some

sample of programming.The proportions of different groups can then be com-

pared to some baseline (generally the proportions of those groups in the real

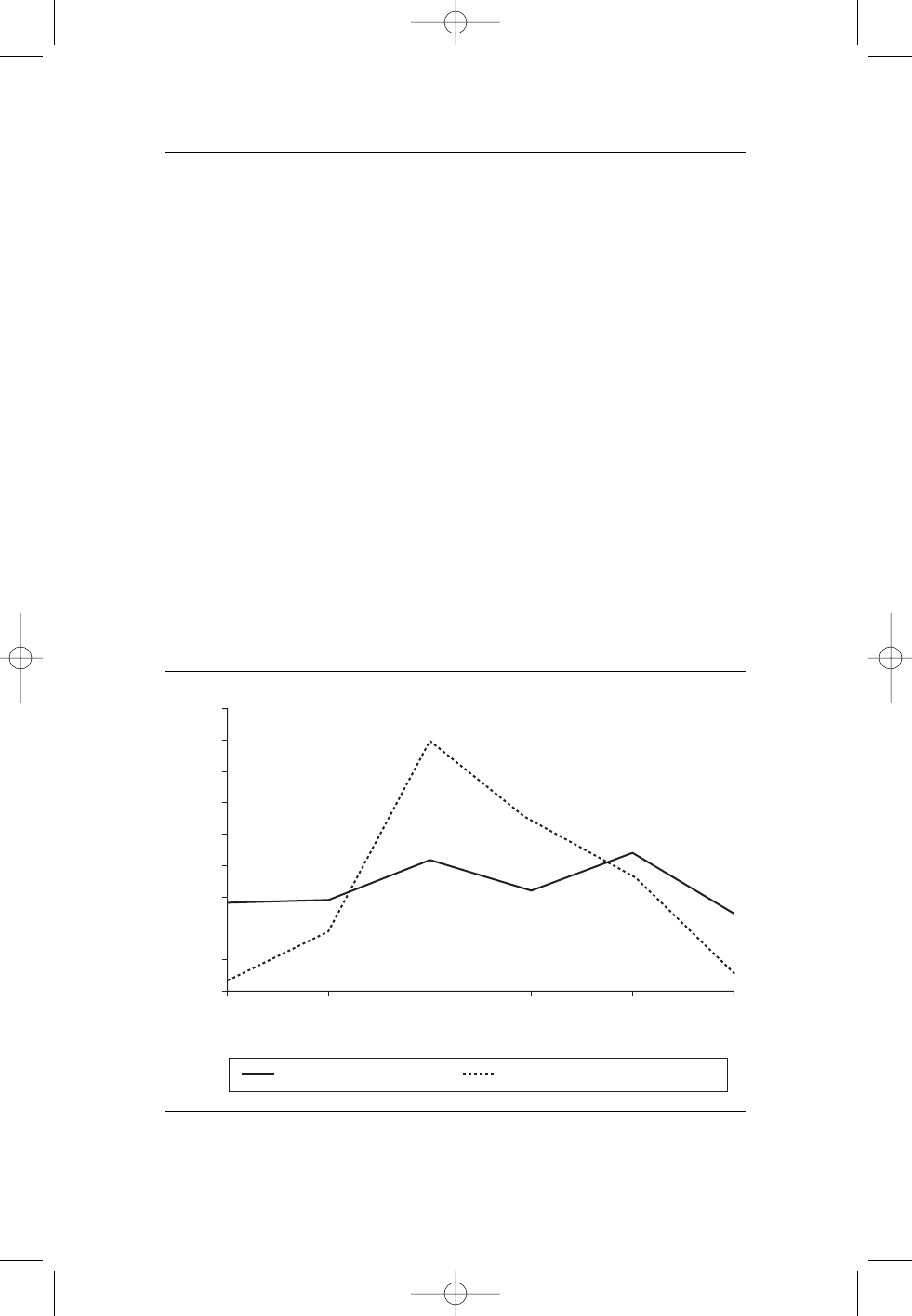

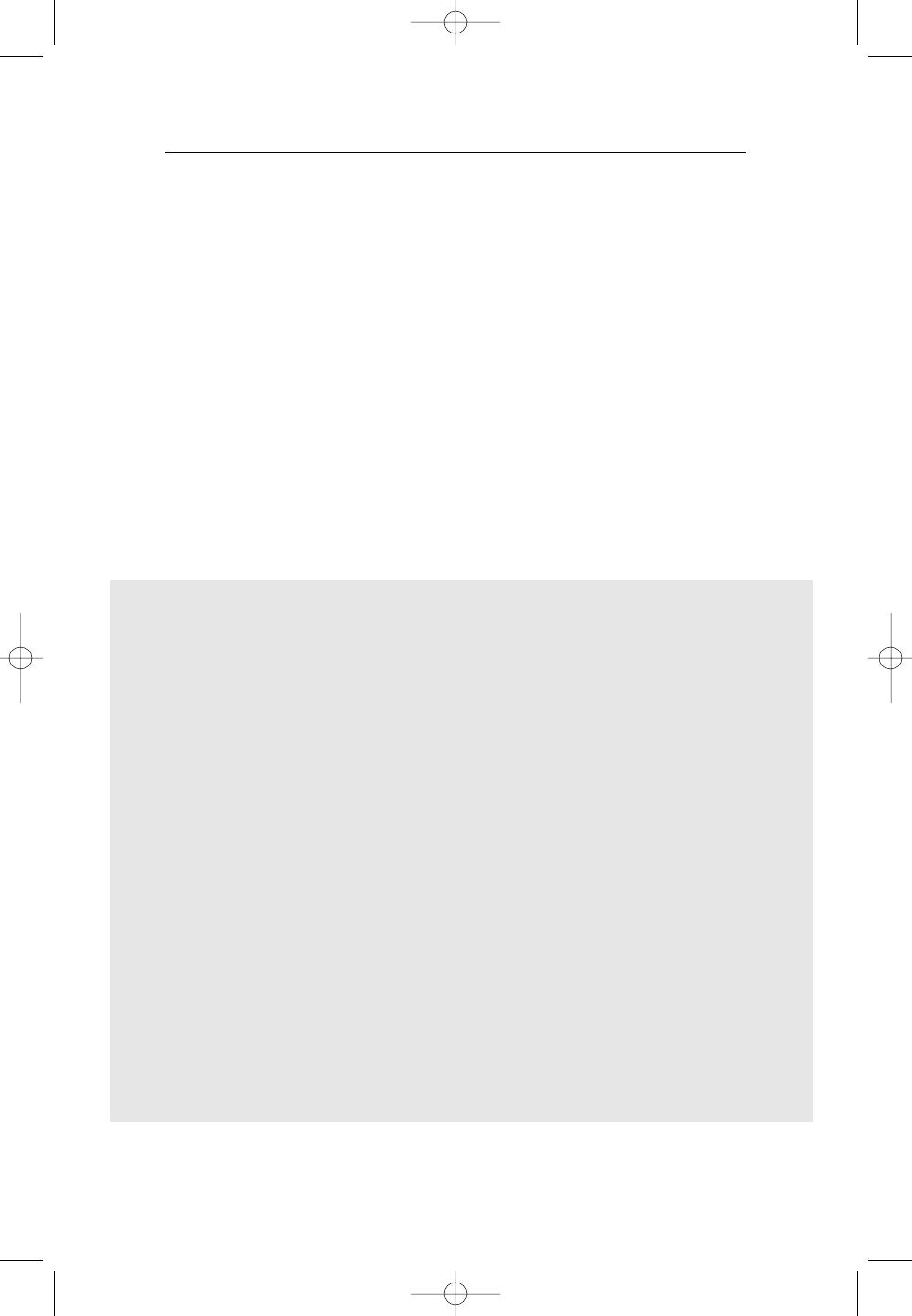

population).Figure 8.1 presents such a comparison for age groups.In this case,

all prime-time major network television shows from 1999 were compared

with year 2000 census bureau data.As you can see,the TV shows contain many

150 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 150

more young adults (20–34 years old) than are actually present in the U.S.pop-

ulation. In contrast, the shows contain significantly fewer older adults. This

phenomenon is called underrepresentation. Older people were about 3% of

the television population,but almost 15% of the real population. Over the past

30 years, results consistent with this pattern have been fairly consistent in the

research literature (Arnoff, 1974; Gerbner, Gross, Signorielli, & Morgan, 1980;

Greenberg, Korzenny, & Atkin, 1980).In general,fewer than 5% of prime-time

television characters are over 65. J. D. Robinson and Skill (1995a) statistically

compared proportions of older adults in different studies over time and

demonstrated that little change has occurred (at least up until that point in

time). The same pattern emerges when television advertising is examined

(Miller, Levell, & Mazachek,2004; Roy & Harwood 1997), and similar patterns

emerge in game shows and cartoons (Harris & Feinberg, 1977; Levinson,

1973). A recent analysis finds that about 8% of characters in children’s car-

toons are portrayed as over 55,as compared to well over 20% in the population

as a whole (T.Robinson & Anderson,2006).

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 151

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Age Categories

Percentage of Total

Year 2000 Census Data 1999 Prime-Time TV Population

10–19 20–34 35–44 45–64 65+0–9

SOURCE: From Harwood,J.,& Anderson,K.,The presence and portrayal of social groups on prime-

time television,Communication Reports,15(2),copyright © 2002.Reprinted with permission of the

Western States Communication Association.

Figure 8.1 Comparison of Prime-Time Television Population With Census

Bureau Data

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 151

Some exceptions have been claimed.For instance,Cassata,Anderson,and

Skill’s (1980) analysis of soap operas is sometimes cited as indicating better

representation of older people in that type of programming. They found that

about 16% of soap opera characters were over the age of 55. However, about

half of those “older adult” characters were in their 50s, meaning that only

about 8% of characters were over 60, and presumably even fewer over the age

of 65. Elliott (1984) also found about 8% of soap characters were over 60 (as

compared to about 14% of the population as a whole).These studies combined

suggest that older adults may not be as severely underrepresented

in soap operas as they are elsewhere, but they are still underrepresented

(Cassata & Irwin,1997). As you can see from this brief discussion, when inter-

preting this research it is very important to know what the “cut-off” is for

someone to count as “old”—comparing people 55 and older on television with

people 65 and older in the population will yield erroneous conclusions of“fair”

representation on television. Petersen (1973) is often cited as the most dra-

matic illustration of older people having a substantial presence on television.

Her study found almost 13% of television characters to be over 65, as com-

pared to about 10% in the population at the time. She was working with a rel-

atively small sample (only 247 characters) and did not report all the details of

her method, but her results remain something of an aberration compared to

the rest of the published literature.One final note: The vast majority of the lit-

erature has focused on entertainment television.Other areas of television may

feature significantly more older people. For instance, in early 2005, Donald

Rumsfeld (Former U.S. secretary of defense) appeared on CNN’s Larry King

Show. Both host and guest were in their early 70s, and both could be consid-

ered very significant cultural figures in the United States at that point in time.

For half an hour, at least, cable news programming was dominated by older

adults.We don’t really know how frequently events like this occur.

Less work exists on media other than television, but that research also

reflects the underrepresentation pattern. Magazine advertisements feature

older adults at substantially lower levels than their presence in the population,

even when a wide variety of magazines are examined (Harwood & Roy, 1999).

For instance, Gantz, Gartenberg, and Rainbow (1980) found that older people

are present in only about 6% of magazine advertisements that include

humans. Ladies’ Home Journal, Ms., People, Playboy,andSports Illustrated all

recorded even fewer ads featuring older people, while only Time and Reader’s

Digest had somewhat larger numbers of such ads.Similar underrepresentation

152 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 152

occurs in children’s literature (Robin,1977),children’s magazines (Almerico &

Fillmer, 1988), newspaper advertisements (Buchholz & Bynum, 1982), and

popular movies (Lauzen & Dozier, 2005). Atkinson and Ragab (2004) exam-

ined the presence of older people in movies from 1980 to 1999, finding about

6% of the characters to be over the age of 60,a slightly higher number than that

of television studies,but still a marked underrepresentation.

As you can see from the dates of the studies cited in the previous para-

graphs, the patterns seem depressingly consistent over the years, with very

little indication of trends toward increased representation of older adults,

despite their growing presence in the population. Miller et al. (2004) exam-

ined television commercials across five decades and found no trend toward

increasing portrayals of older adults (indeed, their data appear to indicate a

peak in numbers of older people in ads in the 1970s). These data, unfortu-

nately,are from a nonrepresentative sample,so the comparisons across decades

may not be valid.Nevertheless,the media seem slow to recognize the growing

presence and influence of this group.

Many researchers have further examined this phenomenon by examin-

ing proportions of men and women in these different media.Again, the find-

ings have been relatively consistent across media and across time. Men are

consistently represented in larger numbers on television and in magazines

than are women, and this pattern tends to be exaggerated among older

people. Gerbner and his colleagues (1980), for instance, showed a huge bulge

of female television characters in their 20s, followed by a dramatic decline.

Women over 40 were rare in their sample. Men, on the other hand, peaked in

numbers in their late 30s, again followed by a relatively steep decline. Raman

and colleagues (Raman, Harwood, Weis, Anderson, & Miller, 2006) show a

similar pattern in magazine advertising, as do Stern and Mastro (2004) in

television commercials (see also Box 8.1).Research has found that older men

appear as much as ten times as frequently as older women (e.g., Petersen,

1973).The most recent research on this issue (T.Robinson & Anderson,2006)

shows a similar pattern among characters in children’s television cartoons—

approximately 77% of older characters on those shows are male.You can do

your own informal survey of this issue using Exercise 8.1.

Interpretations of these findings focus on how men achieve a certain sta-

tus with old age, whereas that status is not accorded to women. This relates,

in part, back to some of the evolutionary explanations for differences in

attitudes about older men versus older women (see Chapter 3). For instance,

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 153

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 153

154 CHAPTER EIGHT

Box 8.1 Women and Men in the Movies

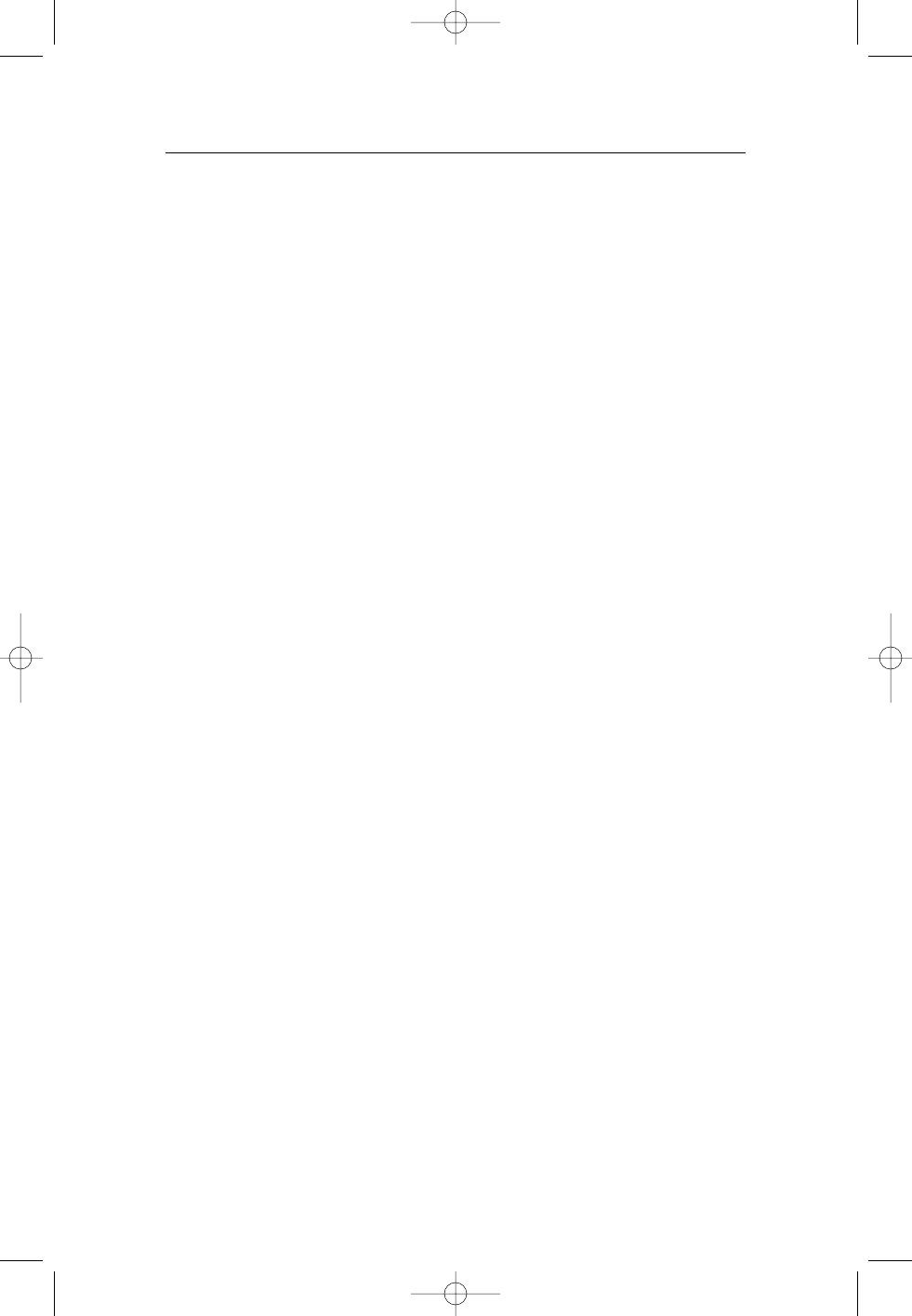

Lauzen and Dozier (2005) examined 88 of the top 100 grossing films in the United

States of 2002 (think, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, Spiderman, Lord of the Rings (Two

Towers), Chicago, etc.).They assessed the age and sex of all characters, as well as

coding each in terms of leadership, role in the film (major/minor), and a number of

other variables.The graph above shows the distribution of male and female char-

acters across different age groups, as compared to those groups’ actual presence

in the population. So values above the zero-point indicate that groups are over-

represented in movies; below the midpoint indicates underrepresentation. As

you can see, movies demonstrate a similar pattern to television and advertising.

Women are overrepresented in their 20s and 30s, whereas men are overrepre-

sented in their 30s and 40s. So men appear to retain a desirability and marketabil-

ity for longer than women. Men and women are underrepresented in movies once

they reach their 50s and 60s, but this underrepresentation is somewhat more

severe for women.The authors of this study also found that men aged 40–69 were

often powerful and in leadership positions, whereas women in these age groups

were less powerful and had less in the way of personal goals. Similar patterns are

shown in a study of 20 years of movie portrayals by Atkinson and Ragab (2004).

NOTE: Y-axis represents percent difference between presence in movies and in U.S.

population. Negative numbers indicate underrepresenation in movies.

Over- and Underrepresentation of Men and

Women of Different Ages in Movies

−5

−10

−12

−20

0

5

10

15

20

Age Groups

Percent Difference

Men Women

13–19 30–3920–29 40–49 50–59 60+

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 154

Gerbner et al.(1980) note that “woman actually outnumber men among [tele-

vision] characters in their early twenties, when their function as romantic

partners is supposed to peak....The character population is structured to

provide a relative abundance of younger women for older men, but no such

abundance of younger men for older women”(p.40). In other words, Gerbner

and his colleagues suggest that the television world is something of a fantasy

situation for older men, who have a positive cornucopia of younger women

from whom to pick a (fantasy) mate.Underlying this is,presumably,an ideol-

ogy in which attractiveness as a mate (reproductive function) is valued above

other factors in determining when and how women are shown on television.

Accompanying this trend for younger women is the fact that women also

seem to take on the more negative characteristics associated with age earlier

than men—women in their 50s are more often categorized as fitting negative

age stereotypes than are men (Signorielli, 2004). Thus, Paul Newman,

Harrison Ford, Clint Eastwood, and many others retain a “sexy” image into

their 50s, 60s, and even later, while thinking of their equivalents among

Hollywood actresses is considerably more challenging.

Work on racial and ethnic disparities in portrayals of older adults is rel-

atively rare and hard to interpret. As noted earlier, there are relatively few

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 155

Exercise 8.1 Gender Bias in Media Portrayals of Age?

Recall the most recent movie you saw. Estimate the age and sex of the two or

three major characters. If you are reading this book as part of a class, summarize

this information for the whole class in the table below. What does it show?

Male Female

0–9

10–19

20–29

30–39

40–49

50–59

60–69

70+

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 155

older adults on television, and among those the majority are portrayals of

whites. For instance, Harwood and Anderson (2002) examined 835 television

characters and found only four African American characters over the age of

60. Statistically it is virtually impossible to reach any conclusions about

representations of older African Americans from such a sample; other ethnic

groups were almost totally absent from the 60+ age group. Research aiming

to examine ethnic variation among older television characters will either have

to examine a gargantuan sample of programs and characters,or it will have to

figure out a way of targeting specific portrayals of particular interest.

Negative Representation

In addition to the underrepresentation of older adults, it is important to look

at how they are portrayed when indeed they are shown. Three predominant

themes emerge suggesting that older people are portrayed negatively in most

media.However, positive portrayals also exist (discussed later),and portrayals

in most media are fairly complex and variable. Beyond the research described

below, you may want to think about portrayals of aging in cartoons (Polivka,

1988), literature (Kehl, 1985; Woodward, 1991), jokes (Richman, 1977) or

popular music (Leitner, 1983).

Health

As described earlier in the book, one pressing concern for social gerontolo-

gists is the almost obsessive societal link between aging and health. As was

talked about in Chapter 1,our society finds it almost impossible to talk about

aging without talking about health, and indeed “aging” is sometimes used to

refer directly to declining health. The media also appear to fall for this link.

Most research examining older people demonstrates that they are associated

with ill health in a variety of ways in media portrayals. One of the best ways

to demonstrate this connection is with advertising portrayals. Raman and

colleagues (2006), for instance, examined the types of products that feature

older adults in their magazine advertisements.In North American advertising,

older people were overwhelmingly associated with health-related products.

Interestingly, many of these products were for ailments that are not particu-

larly age-related (e.g., allergy medications), although some were for products

with clear age connections (e.g.,incontinence treatments,Alzheimer’s drugs).

As will be described below, the individual portrayals of older people in these

156 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 156

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 157

ads are not necessarily negative. The concern is with the perpetual linking of

age and health, which reinforces the connection between those two things.

Sometimes, we see dramatic illustrations of ways in which individual deci-

sions such as those of headline writers can change whether a media portrayal

emphasizes decline in old age—often a subtly different spin can have dra-

matic consequences (see Box 8.2). Chapter 11 has more detailed coverage of

specific communication and health issues in older adulthood.

Box 8.2 Mass Communication About Aging: A Case Study—Are Older

Surgeons’ Patients More Likely to Die?

In early September 2006, I noticed a headline in my local newspaper.“Study:

Aging Surgeons Less Effective in Some Surgeries.” Being interested in aging,

I read the article. It appeared to report that patients of older surgeons die

more often, but the exact findings of the original study on which the article

was based weren’t entirely clear. Google news quickly directed me to other

articles based on the same original study. All of the articles included basically

the same information, but the headlines varied quite dramatically in terms of

their implications about older surgeons’ skills. Consider the following:

Study Raises Questions About

Aging Surgeons’ Last Years

Older Surgeons Not

Necessarily Better

Old Surgeons Still Good—If Busy

Are Older Surgeons Better?

Study: Surgeon’s Experience

as Important as Age

Study: High-Volume Surgeons Best

Age of Surgeon Is Not

Important Predictor of Risk

for Patient

With Surgeons, Older May Not

Be Better

Aging Surgeons Under

Scrutiny

Surgical Work Can Outlast

Skills

When Should Surgeons Hang

Up Their Scrubs?

Study Questions Surgeons’ Last

Years Behind Scalpel

I was immediately struck by how the same original information could be pre-

sented in so many different ways, and I was particularly concerned about the

impact that these different headlines might have on a reader who was quickly

(Continued)

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 157

scanning the newspaper. Some appear to suggest that there are significant

problems with older surgeons, while others explicitly say that age is not

important, and some don’t mention age at all. In this case, the headline writ-

ers have interpreted the results of the original study and either emphasized

or deemphasized the role of age.What was the actual finding of the study?

Older surgeons’ patients did die more often for three of eight types of

surgery examined (they were equal on five of the eight). But that death rate

was because more of the older surgeons were performing relatively few

operations—they were getting less “practice” than younger surgeons. Older

surgeons who maintained a regular surgical load had performance that was

as good or better than younger surgeons. There are three morals to this

story:(a) If you’re getting a surgery done, you should ignore the surgeon’s age

but make sure you ask how often the surgeon performs the specific proce-

dure that you’re about to undergo, (b) when you read a newspaper headline

suggesting a link between age and some other variable, try to dig a little

deeper and see what the original research actually found, and (c) if you are

writing newspaper headlines, don’t jump to a conclusion based on one piece

of information—consider the effects on your readers when stating a conclusion

like “aging surgeons less effective.”

158 CHAPTER EIGHT

(Continued)

Lead Versus Peripheral Roles

A frequent observation of scholars examining older adults on television is

that they are rarely shown in major roles.J.D.Robinson and Skill (1995b) have

developed a theoretical perspective surrounding this phenomenon: periph-

eral imagery theory. This theory suggests that minor or peripheral charac-

ters in a media presentation may be more revealing than central characters as

concerns societal portrayals. Specifically, major characters in television

shows,for instance,tend to develop over time, have idiosyncrasies,and have a

detailed back story that allows us to view them as a complete person. Minor

characters, on the other hand, are present for a short period, serve some

rather specific plot function, and then disappear. As such, they need to be

processed and understood rather quickly by the audience.In doing this quick

processing, it is likely that the audience relies on schemas or stereotypes

about the groups that the characters come from. Thus, the writers will create

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 158

characters that fit with the audience’s schema. For instance, if you need a

character who is hard of hearing in order to make a joke work,having an older

person serve that function will work best. Their poor hearing fits the viewer’s

schema of old age, and hence the writer doesn’t have to spend valuable time

explaining that they are deaf.Thus,the fact that older adults are often present

in peripheral roles enhances the likelihood that they will be portrayed in a

stereotypical fashion. One disclaimer: Some studies do not support the con-

tention that older adults are shown more frequently in peripheral roles (e.g.,

Harwood & Anderson, 2002). The diverging findings on this issue may be a

function of the relatively small number of older adults on television; when we

are only looking at a relatively small number of older characters, it becomes

statistically challenging to examine subtle issues like whether they are por-

trayed peripherally in larger numbers than other age groups. Either way,

peripheral characters are important to examine because of the ways that they

reveal stereotypical images (J. D. Robinson, Skill, & Turner, 2004).

Humor

Funny messages are a media staple: From blockbuster comedy movies and

network situation comedies to basic cable’s Comedy Central channel, comedy

is ubiquitous. Older people and aging are used a lot for comic effect, often in

less-than-flattering ways. Comedy can be achieved by having a stereotypical

older character who is the butt of other characters’ jokes (e.g., the dirty old

man, the forgetful aging parent). Such messages obviously rely on shared

knowledge of the stereotype for their humor and almost certainly serve to

reinforce that stereotype. An advertising campaign for baseball on the Fox

network featured an 89-year-old ex-baseball player supposedly making a

comeback. One spot showed the man attempting to pitch: “After lobbing a

massive gob of spit onto a baseball, he weakly throws the ball a mere couple

of feet”(Petrecca, 1999, p. 8).

Messages About the Aging Process

In addition to actual portrayals of older people, the media send a variety of

messages about the aging process that can be construed as negative. Perhaps

most salient here are the advertisements for cosmetics that promote

“younger” skin, moisturizers that have “anti-wrinkle” formulas, and dyes

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 159

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 159

developed specifically to hide grey hair. While we have grown accustomed to

these products and probably don’t think twice about them, the marketing of

them is explicitly ageist. The premise is that we all want to hide any signs that

we are aging, and that this is natural and normal. Justine Coupland (2003)

makes a powerful argument that cosmetics advertisers not only want to make

aging skin seem pathological but also want to induce guilt in women by mak-

ing women themselves feel “responsible”for wrinkles. Note that this is a very

gendered discourse,with women being targeted massively more than men for

such products. The message is one that is clearly opposed to the visible man-

ifestations of aging,and hence is ageist.All this occurs,despite the fact that (to

quote J. Coupland),“to live in the world is to age, day by day, from birth. How

can advertisers persuade women that stopping the ageing process or, rather,

disguising its effects on the body is achievable?”(p. 128).

Other troublesome messages about aging occur in the media’s use of

phrases like “senior moment” (Bonnesen & Burgess, 2004), descriptions of the

physical status of “veteran” athletes (often in their late 20s!), and perhaps even

in advertisements for financial services for retirees that tend to focus on leisure

activities and do not portray the many constructive ways in which older people

contribute to society. Even more destructive messages are present in media like

birthday cards,but of course such messages are intended to be funny,and hence

their creators would perhaps argue that they are harmless. I would disagree!

There is very little research on these kinds of portrayals or their effects on

people who see them. If you are reading this book as part of a class, you might

want to discuss some ways in which some of these forms of communication

talk about the aging process: Take a look at Dillon and Jones’s (1981) study of

birthday cards and then visit your local Hallmark store to sample the wares.

Positive Portrayals

There are a few areas in which it is possible to identify positive elements in

portrayals of older people,although in some cases these need to be subject to

some critical thinking.Some researchers describe positive media portrayals

of aging without a clear comparison point. For instance, Vernon, Williams,

Phillips, and Wilson (1990) describe positive portrayals of older people in

prime-time television on a variety of dimensions.However,they have no com-

parison with the portrayal of younger people, so we can’t know whether these

160 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 160

“positive” portrayals are different from (i.e., less positive than) portrayals of

younger characters.Likewise, Cassata et al.(1980) describe generally positive

portrayals of older people in daytime soaps, but again without a comparison

to younger people.Kessler, Rekoczy, and Staudinger (2004) engage in a rather

complicated analysis attempting to compare older adults’ portrayals to some

objective standards of life success.They suggest that portrayals of older adults

in German television are positive. Again, however, we do not know whether

portrayals of younger people are even more positive because portrayals of

younger people were not examined.This is a crucial point: It may be that older

adults are not portrayed in an overwhelmingly negative fashion, but they are

nevertheless portrayed less positively than young people.

Certain apparently positive portrayals also require a somewhat more

detailed examination to understand the complex ways in which older people

are shown. Next we consider some common areas of apparently positive por-

trayals. The filmography in Box 8.3 provides a list of movies that should lead

to interesting discussion about portrayals of aging.

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 161

Box 8.3 Filmography of Interesting Portrayals of Aging

The following are movies with positive, interesting, or controversial por-

trayals of aging. I am not recommending these as the best images of aging

that are out there. Rather, they are movies that give interesting starting

points for discussing how the media portray aging. In many cases,they also

provide interesting perspectives on intergenerational relationships, some-

thing that has not been studied extensively. I have also included films on

different portions of the life span: Portrayals of middle age (e.g., The Big

Chill) are interesting in that they often present people first coming to

terms with their own aging.It is crucial to watch the movies critically, con-

sidering the ways in which they present aging as a diverse and positive

experience, the ways in which they stereotype the older characters, and

the ways in which aging is at times sentimentalized. If you are reading this

book as part of a class, you might want to watch one of the movies and

discuss its portrayal, or divide them up among the class, and share the dif-

ferent narratives of age that you see with one another. I have also included

a few television shows that have interesting portrayals of older people.

(Continued)

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 161

A Woman’s Tale

Babette’s Feast

Cinema Paradiso

Crimes and Misdemeanors

Curtain Call

Dad

Driving Miss Daisy

Fried Green Tomatoes

Grumpy Old Men

Innocence

Iris

Lost in Yonkers

Rocket Gibraltar

Something’s Gotta Give

Space Cowboys

The Big Chill

The Dresser

The Gin Game

The Notebook

The Straight Story

Tuesdays With Morrie

The Golden Girls (TV)

King of Queens (TV)

Frasier (TV)

The Simpsons (TV)

Murder, She Wrote (TV)

Everybody Loves Raymond (TV)

162 CHAPTER EIGHT

Exceptional Characters

Older adults who have engaged in activities that are dramatically counter-

stereotypical (going against the stereotype) are a staple of “human interest”

sections of newspapers and local TV news—the classic case here is the 83-

year-old grandma who jumps out of an airplane. Older adults who

run marathons, cycle across the Rocky Mountains, climb Everest, or get shot

out of canons are subject to similar treatment. Little research has been done

on these portrayals, but they do seem to share similar features. Most notably,

the exceptionality of these achievements is a common theme (the older adults

concerned are described as remarkable, amazing, fantastic, and the like).

Most of the stereotype violations are positive, but sometimes these individu-

als have violated stereotypes in a negative fashion (e.g., in December 2005, a

70-year-old grandmother achieved some notoriety when she stole the baby

Jesus from a nativity scene:“Granny Lifts Baby Jesus,” 2005).

Clearly such portrayals might have the capacity to change our perceptions

of aging, given that they feature individuals who have ignored the constraints

that society places on old age, instead choosing to pursue exciting and gener-

ally personally rewarding activities. However,the very newsworthiness of these

(Continued)

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 162

achievements, and the way in which these older people are portrayed as

exceptional, tends to discount any positive impact that the stories might have on

our more general views of older people. The focus on the individuals as excep-

tional makes it clear that a typical older adult does not do these things, and per-

haps that they should not. One skydiving grandma is on the news precisely

because she is doing something that is not representative of most old people.You

may wish to refer back to Chapter 7,which discussed the role of representative-

ness or typicality of older adults in having the potential to change attitudes.

Central Characters

The exceptional or atypical portrayals described above are also apparent in

some fictional characters—generally they tend to be the lead characters in

shows. While older adults are rarely lead characters in shows, when they

are the leads, they often portray older adulthood in apparently positive and

almost always counter-stereotypical ways.The most commonly discussed of

these in recent years is The Golden Girls, which aired on NBC from 1985 to

1992 but is still showing in syndication. Other similar shows are Murder, She

Wrote, Diagnosis Murder, Matlock,andJake and the Fatman. These shows

often capitalize on particular star power. A show like The Golden Girls that

features four older women would be a very tough sell to most network execu-

tives (see below). However, when it includes recognizable stars like Estelle

Getty,Bea Arthur,and Betty White,it comes with a built-in audience of people

who like those actresses,and thus is sustainable.Similar star power is apparent

on Murder, She Wrote (Angela Lansbury), Matlock (Andy Griffith), and other

such shows. These shows thrive among the older audience because,as will be

elaborated in the next chapter, older people generally like shows that feature

older characters. Hence,while The Golden Girls was popular across the whole

television audience (“Best and Worst by Numbers,” 1989), it was consistently

a huge ratings winner among older viewers (Mundorf & Brownell,1990).This

audience can be attractive to certain subsets of advertisers (e.g., financial

organizations offering retirement planning).

Bell (1992) examined a number of shows featuring older characters

as the leads in the late 1980s and concluded that the older characters were shown

as affluent, healthy, active, admired, and sexy. Such portrayals are in stark

contrast to the “average”portrayals of older adults that are negative (as described

above; remember that J.D.Robinson and Skill (1995b) suggested that peripheral

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 163

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 163

characters tend to be more stereotypically portrayed than leads). Lead charac-

ters necessarily involve more complexity than peripheral characters, and they

also need to be more likeable.Thus, in the rare instances where older characters

get to be the lead in the show, they are likely to be positively portrayed.

Unfortunately,a few factors make these lead characters’positive portrayals

less exciting than we might hope. First, as described in more detail in the next

chapter, younger people are unlikely to watch these shows. Hence, no matter

how positive the portrayal, younger people are unlikely to see it or be affected

by it! Second, such portrayals may be less positive than you might imagine for

some older people.In particular,Mares and Cantor (1992) show that some older

people (those who were coping less well with their own aging) found the highly

engaged,active,and competent characters on television to be somewhat threat-

ening.Third,there appears to be a decline in this kind of programming.During

the late 1980s and early 1990s a number of shows with older adult leads main-

tained lengthy prime-time runs (see those listed above). In contrast, it is diffi-

cult to think of a current prime-time network show with a lead character over

the age of 60.A fourth concern is that these portrayals (as well as the news por-

trayals of exceptional older adults described in the previous section) may at

times have a humorous intent, an issue that we turn to next.

Humorous Characters

In some of my earliest research, Howard Giles and I looked at images of aging

in The Golden Girls (Harwood & Giles, 1992). We concluded that the show did

do a good job of contradicting a number of stereotypes of old age (for instance,

the characters are shown as active, healthy, and sexual). However, we also

expressed concern that the humor in the show often centered around ageist

stereotypes in unfortunate ways. For instance, the character Blanche is the

most sexually active of the characters, and her sexual exploits are often the

subject of jokes in the show, which might serve to reinforce the idea that all

sexual activity in older people is absurd. Indeed, when characters engaged in

activity or said something that was counter to age stereotypes, the vast major-

ity of the time it was associated with laughter on the show’s laugh track.

Advertising messages also sometimes capitalize on portraying older

adults in ways that violate our stereotypes, and again, these messages often

rely on humor.A 2005 beer commercial features an older woman (fairly short

and plump, with grey hair) in a martial arts class. Her instructor is clearly

164 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 164

very skilled, but the older woman appears passive. However, when her

instructor takes her beer away, the older woman immediately launches into a

series of violent and very effective martial arts moves,bringing her black belt

instructor to his knees. The message relies on violating the stereotype of

“grandmotherly” behavior to achieve its humor. While it might superficially

be seen as a positive portrayal of aging (the woman is physically strong and

powerful),the humorous intent removes any likelihood that it might be inter-

preted in a liberating way for older people. This is, of course, only one adver-

tisement. The next section concerns more general patterns in advertising.

Advertising

In contrast to the negative portrayals commonly found elsewhere, advertising

images of seniors tend in large part to be positive. For instance, Roy and

Harwood (1997) found that older characters in television ads tended to be

happy and active (see also Atkins, Jenkins, & Perkins, 1991; Swayne & Greco,

1987).The same has been found with magazine advertising (Harwood & Roy,

1999). In part, of course, this can be explained by the nature of advertising.

Ads are trying to sell products, and it is pretty rare for advertisers to want to

depress their audience or make them unhappy. Indeed, in a recent examina-

tion of magazine advertising that I was involved in, we found happy, smiling

older adults in advertisements related to Alzheimer’s disease,long-term insti-

tutionalization, and loss of bladder control (Raman et al., 2006).

Currently, there are some interesting trends in the ways that ads are

using the grandparenting relationship to sell products. A number of recent

ads include the implicit message:“Use our product and you can have a better

relationship with your grandchild.” Figure 8.2 provides one example. The

product being advertised is designed to help improve lung functioning for

people with a specific ailment. The improved lung function is illustrated by

the ability to blow bubbles and hence entertain the granddaughter.Obviously,

being able to blow bubbles is not the primary advantage of having good lungs.

But the image in the ad provides a positive spin on the product—rather than

emphasizing current limitations and problems,it emphasizes future possibil-

ities.And in presenting this somewhat idealized image of the relationship, it

manages to associate the product with an uncontroversially positive thing:

Very few people are opposed to grandparents and grandchildren having fun

together, and so people should be in favor of this product.

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 165

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 165

Researchers in Britain have recently begun looking at advertisements fea-

turing older adults in a more detailed, qualitative fashion, focusing especially on

visual communication cues in the advertisements. This work has begun to pro-

vide some categories in which we can place different kinds of portrayals. For

instance, sometimes older people are shown as comic or ridiculous (e.g., a very

old man dressed in teenage clothing styles), other times they are shown as

glamorous and wealthy (e.g., a well-dressed couple dressed up for a night on the

166 CHAPTER EIGHT

Figure 8.2 Advertising Featuring the Grandparenting Relationship

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 166

town),and sometimes they are celebrities endorsing a product (Ylänne-McEwen

& Williams, 2003). These researchers have suggested that some advertisements

are now featuring older adults in an “age incidental” fashion—the age of the

characters in the ads is irrelevant to their portrayal. This is an interesting trend

in that old people are (too) often portrayed precisely for their age status—that

is, the fact that the person is old brings some humor or information to the ad,

and the older person would not be there otherwise.To have older people in an ad

in a non-age-relevant fashion perhaps demonstrates some more general accep-

tance of aging and old age in society such that these people are welcome to

simply play the role of a person, rather than always being an old person.

Miller et al. (2004) present data suggesting that older adults are being

shown more positively in commercials today than they were in the past.Using

Hummert’s “multiple stereotypes” perspective (see Chapter 3), they coded

older characters in television commercials over five decades.The results indi-

cate that, for instance, an active “golden ager” stereotype is represented by

about 50% of older characters in the 1980s and 1990s,but less than 30% dur-

ing the 1950–1979 period. Conversely, negative stereotypes of older adults

seemed to be used a lot in the 1970s but not at other times. These results are

intriguing, and this study also represents one of only a few pieces of research

that incorporate some of the stereotyping work from Chapter 3 into media con-

tent analysis. The samples of ads from each decade are not necessarily com-

parable,however, because they were not randomly sampled.

Overall,though,advertising does appear to be one area in which positive

portrayals are fairly common. Indeed, there are some indications that adver-

tising may be at the leading edge of genuinely positive, and even liberating,

portrayals of older adults. A recent billboard for a soap product shows a

woman’s face with visible wrinkles and long grey hair: She is probably in her

mid to late 50s, so she is not “old” in the sense that is typically used, but she

is definitely showing signs of aging. She is smiling, and beside her are two

simple check boxes saying:

Grey?

Gorgeous?

The message is a new one: That it’s OK to celebrate the physical manifesta-

tions of aging, and that it might even be possible to see some of those markers

as attractive.Unthinkable? Think again! See Exercise 8.2 for some recent adver-

tisements: Are these sending positive or negative messages about age?

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 167

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 167

168 CHAPTER EIGHT

Exercise 8.2 Portrayals of Aging in Advertising

Compare and contrast the advertisements on the next two pages. What

message(s) does each send about getting old? Consider alternatives, and think

about why the creators might have made the messages ambiguous and what they

were trying to achieve. When examining the advertisements, consider the following

issues:

a. What is the visual image of the older people? What are their facial expressions?

How are they dressed?

b. Does the text make reference to age or aging? How? Does the language that

is used in the ad send any messages about aging?

c. Are there similarities between these ads and the one shown in Figure 8.2?

d. How are relationships portrayed in the advertisements? Which relationships

are described/discussed, and with what effect?

e. Overall, what effects might come from exposure to multiple similar messages?

How might these messages make younger and older people think about aging,

personal relationships, or the products/services being advertised?

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 168

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 169

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 169

Political Power

Holladay and Coombs (2004) discuss some common media images of older

adults’ political power. These authors note that the media present groups

like the AARP as “nearly omnipotent” in Washington, DC, driving policy

making and striking fear into legislators with threats of how their older

constituents will vote based on senior-related policy issues. The AARP

170 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 170

certainly does exercise political power in Washington:It is a respected author-

ity on aging issues, and it has the ability to mobilize large numbers of seniors

on particular issues. However, as Holladay and Coombs note, older people

virtually never vote as a block—older adults’ political attitudes and voting

behavior are at least as diverse as any other group. Hence, the AARP has not

demonstrated the power to shift election results.Perhaps as a consequence of

this, its direct effects on new policy have been limited. The frequent over-

statements of the AARP’s influence in Washington do, however, have some

rather negative consequences. In particular, Holladay and Coombs note that

these portrayals reinforce notions that older adults are “greedy geezers,” and

that their political activities are entirely grounded in self-interest. More

broadly,the portrayals of the AARP’s political power reinforce ideas that older

adults are being looked after in the political realm, which is at best only

partially true.

The Media Industry

We turn now to a brief discussion of media industry issues to help under-

stand what has been described in this chapter.The low levels of older adults’

media portrayals and lack of positive change over time might be seen as

somewhat surprising given that the U.S. media examined in most of these

studies are private, commercial enterprises. U.S. commercial media rely on

attracting audiences, and older adults are a large and growing audience.

The U.S. population 50 and older owns $7 trillion in assets and has around

$800 billion in personal income (70% of the total net worth of American

households: L. Davis, 2002). Such a group would seem like a good target for

television programmers and advertisers alike.So why are older people being

ignored?

Obviously, decisions about the content of television shows (what the

show is about,who the main characters will be) are made by groups of people.

The decision to “green light” (approve for production) a television show is an

expensive one for a media organization, and one that is only made when the

organization is confident that the show will gain a viewership, and thus be

attractive to advertisers. Don’t forget: The main goal of network television is

not to make shows that entertain you. Their main goal is to deliver an audi-

ence of people to advertisers.

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 171

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 171

One commonly cited issue with portraying older people on television is

that such characters do not appeal to younger viewers, and many advertisers

are very concerned with getting their products in front of younger consumers.

Adults aged 18–49 are often referred to as“key demographics”(or just “key

demos”) within the media industry.The show that wins among the key demos

can be a bigger deal than the show that gets the most viewers overall.Why?

Young people are also often believed to have more disposable income (i.e.,

they have cash in their pocket that they are willing to spend). It is true that a

greater proportion of older people’s assets is tied up in things like stocks and

real estate. If you have paid off your mortgage and own your home outright,

you have control of a very significant asset, but you can’t buy a can of soda

with that asset! However, in terms of pure dollars, older adults control more

discretionary income than any other group (Polyak, 2000). While we don’t

have a lot of research to go on, it seems likely that older adults are somewhat

smarter with their discretionary spending than young people, however. So,

while younger people might be attracted by a well-made commercial, older

adults have a lifetime of experience with consumerism and may be somewhat

more skeptical of advertisers’ claims. Perhaps they are less likely to be influ-

enced by a 30-second advertisement and hence are less attractive to adver-

tisers trying to sell things to us.There is also the impression (largely false)

among advertisers that older consumers have decided on their brand and are

unlikely to switch (e.g., if she’s driven a Buick all her life, she’s not going to

change now!). David Poltrack (a researcher for the CBS television network)

has argued against this by citing the example of the Lexus car brand, driven

mostly by people over 50.In 2000,he said:“Lexus is a car that didn’t exist four

years ago, so how did these older people come to buy it; did they think they

were buying a Cadillac?” (quoted in Briller, 2000). Perhaps the philosophy

of targeting key demographics has reached its pinnacle with Fox’s American

Idol, a show in which anybody over the age of 28 is too old to participate

(http://www.idolonfox.com/).

A final problem is that the desire for younger viewers may drive a desire

for younger people to write and produce media content. Thus, not only are

older adults excluded from media content,they may also be excluded from the

process of media production: People who have worked hard to “make it” in

Hollywood may suddenly find themselves kicked out once they pass a partic-

ular age hurdle (see Box 8.4).

172 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 172

Box 8.4 Age Discrimination and Media Writers

In October 2000, in the case Wynn et al. v. NBC et al., a group of TV writers

began a discrimination claim against the television industry. Over the

subsequent years, this case has grown into one involving 23 separate class

action lawsuits filed against numerous television production companies and

involving hundreds of television writers. The claim is one of age discrimina-

tion: that television companies and talent agencies denied opportunities to

writers and paid writers less for their work based purely on their age (see

www.writerscase.com for current status information). The case is still in the

legal system, but academic research on the topic suggests that the plaintiffs

might have a case. Bielby and Bielby (2001) studied employment and mone-

tary compensation for writers across different age groups. The graphs below

show somewhat dramatically what was found in terms of compensation.

There is a steady decline in the amount that writers are paid as they get

older. Also, note that the declines are steepest for the most recent date

(1997) implying that discrimination got worse between the mid 1980s and

the early 1990s.Whether or not illegal discrimination has occurred is up to

the courts. But it is clear that the people who determine the content of the

media do not represent the diversity in their audience, and this may play a

role in explaining the relative homogeneity in the messages we see. While

organizations like the NAACP have been successful in increasing the pres-

ence of African Americans both in front of the camera and in the creative

process, there is little in the way of such advocacy for older adults.

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 173

$40

Age Category

Film

Predicted Earnings in Thousands

$20

$30

$10

$0

11–30

30–39

40–49

50–59

60

–64

65

+

1997 1993 1989 1985

Net Age-Earnings Profiles of Film and Television Writers

for Selected Years, 1985–1997 Predicted Dollar Earnings by Age Category

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 173

Summary

The work described in this chapter demonstrates conclusively that media

portrayals of older adults are neither fair nor realistic. Older adults are not

portrayed in accord with their real presence in the population, and they are

rarely shown in ways that represent the true experience of being old in all its

depth and breadth. In large part, this unfortunate pattern of portrayals is

reinforced by the commercial demands of the industry, as well as ingrained

patterns of industry behavior, including perhaps age discrimination against

writers. Future research on portrayals of older adults could usefully focus on

three issues. First,it would be useful to develop ways of measuring variability

in portrayals of older people. As was talked about in Chapter 7, our under-

standings of social groups don’t just consist of positive versus negative. We

also have perceptions of how much variation there is within groups (“Oh,

they’re all the same”). Television portrayals may contribute to homogeneous

perceptions of older people if the portrayals lack variation. Right now, we

don’t know much about how varied television portrayals of older people are,

174 CHAPTER EIGHT

SOURCE: From Bielby & Bielby (2001).

$40

Age Category

TV

Predicted Earnings in Thousands

$20

$30

$10

$0

1997 1993 1989 1985

11–30

30–39

40–49

50–59

60

–64

65

+

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 174

relative to variation among portrayals of younger people. My hypothesis is

that older people are portrayed as being rather similar to one another.

Second, it would be useful to examine whether the older people who do

exist on television are clustered in a limited number of shows. This is clearly

the case with other groups; for example, although African Americans are now

present on television in larger numbers than in the U.S. population, they are

not evenly distributed. Certain shows on certain networks are “black” shows

and feature almost entirely black casts,while the majority of shows are “white”

shows.It’s not clear whether this pattern also occurs with older characters.

Finally, we need more systematic research on messages about aging.

When do words like “old”or “elderly”or “aging”get used on television and in

other media,and in what context? The media clearly inform our understand-

ing of lots of topics,and it’s time to understand in more detail exactly what the

media are telling us about getting older.

Keywords and Theories

Mass Communication Portrayals of Older Adults 175

Advertising

Counter-stereotypical

Evolutionary explanations (for sex

differences in portrayals of age)

Green lighting

Humor

Key demographics (key demos)

Negative and positive portrayals

Peripheral imagery theory

Underrepresentation

Discussion Questions

• Which current shows feature older characters? Which of those characters would you

regard as positive portrayals, and which as negative? Are the portrayals lead charac-

ters or peripheral characters?

• Do members of your family watch shows featuring different aged characters? Which

shows? Why?

• Examine the advertisement in Exercise 8.2.What are the possible messages that they

are sending about old age?

• Think about a recent portrayal of an older person that you saw in a television or mag-

azine advertisement.What message(s) is it sending about aging?

• Do you agree that women should buy products to reduce the visible signs of aging?

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 175

Annotated Bibliography

Bielby, D. D., & Bielby, W. T. (2001). Audience segmentation and age stratification among

television writers. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 45, 391–412. A fas-

cinating article on the age of television writers and their employment status and pay.

While at times it gets a little technical, it is one of the few articles to address issues

of age behind the camera, compared to a relatively large number of studies that

examine portrayals of age.

Kessler, E.-M., Rekoczy, K., & Staudinger, U. M. (2004). The portrayal of older people in

prime time television series: The match with gerontological evidence. Ageing and

Society, 24, 531–552. An article presenting a very detailed analysis of older adult

portrayals on German television.The approach of the authors is novel, in that they

attempt to compare older people on television with the “real” status of older people

in society.They conclude on this basis that certain portrayals are overly positive: that

television in some cases may actually be too positive about aging issues. Such con-

clusions are unusual in a literature that is obsessed with how negative most por-

trayals are, so the article deserves reading.

Neussel, F. (1992). The image of older adults in the media: An annotated bibliography.

Westport,CT: Greenwood Press.This book is now a little outdated,but still an amaz-

ing resource. It contains citations and brief descriptions of a massive range of stud-

ies of how older adults are portrayed across multiple media contexts. It provides

particularly thorough coverage of the wide range of studies on portrayals in litera-

ture. The current chapter did not examine that work because much of it is in the

form of a more “literary” perspective rather than a communication perspective.

Nevertheless, such work is very interesting.

176 CHAPTER EIGHT

08-Harwood.qxd 4/10/2007 7:28 PM Page 176