1

Student Handbook

MSW Program

Updated 2017

We strive to be supportive and responsive in helping you cope with the academic,

personal, and internship demands of graduate school. This support begins by

making certain you know how to locate the wide variety of resources available to you.

As graduate students and beginning professionals, you are responsible for familiarizing

yourself with all School policies, procedures, guidelines, and program requirements.

The Student Handbook and School policies are available on the SSSW

website. Please check the website regularly for important, up-to-date

information: sssw.hunter.cuny.edu.

3

Table of Contents

Mission Statements & Goals ....................................................................... 7

1. The MSW Program .................................................................................. 9

Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 9

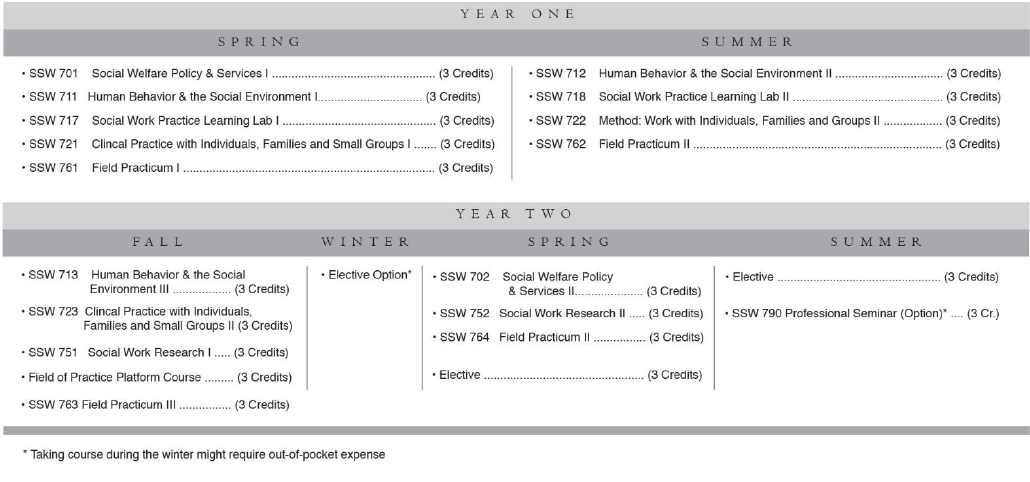

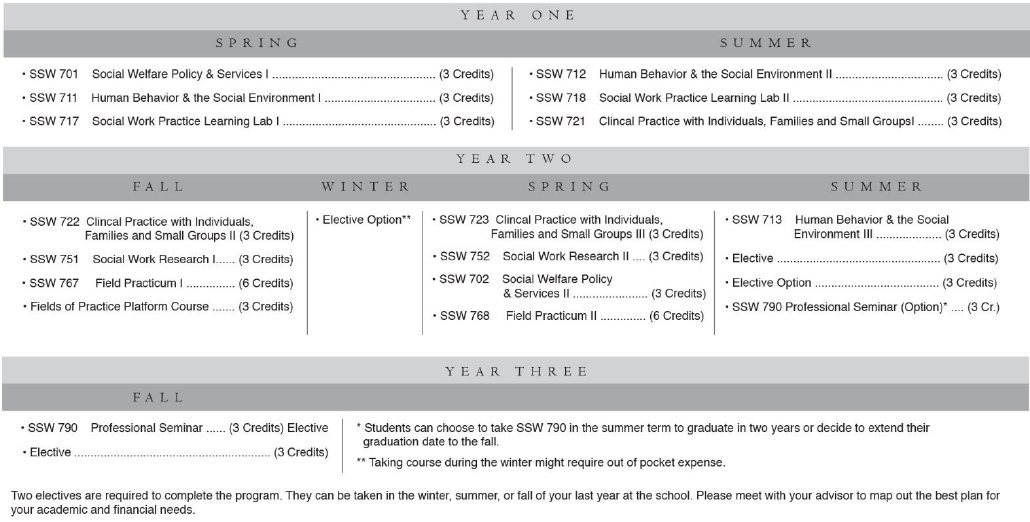

Programs of Study – Pathways to the MSW Degree ...................................................................... 9

Change of Degree Pathway ........................................................................................................... 11

2. Curriculum of the MSW Degree Program ............................................... 12

CSWE Core Competencies & Practice Behaviors: Clinical Practice ............................................... 12

CSWE Core Competencies & Practice Behaviors: Community Organizing, Planning &

Development................................................................................................................................. 15

CSWE Core Competencies & Practice Behaviors: Organizational Management & Leadership .... 18

Method Concentration ................................................................................................................. 21

Change of Method Concentration ................................................................................................ 21

Additional Program Requirements ............................................................................................... 21

Attendance Requirements ............................................................................................................ 23

Summer Session ............................................................................................................................ 23

Fields of Practice Specialization .................................................................................................... 23

3. The One-Year Residency Program (OYR) ................................................ 25

The OYR Program: Overview ......................................................................................................... 25

Time Frame I: Part-time Evening Courses .................................................................................... 25

Time Frame II: Residency Year ...................................................................................................... 25

Time Frame III: Finishing Up ......................................................................................................... 27

4. Field Practicum ...................................................................................... 28

Field Practicum Overview ............................................................................................................. 28

Field Practicum Policies................................................................................................................. 35

5. Field Advising ........................................................................................ 41

Overview of the Field Advisor’s Role and Responsibilities ........................................................... 41

Group and Individual Advisement ................................................................................................ 41

Evaluation of Student Performance .............................................................................................. 42

Handling Field Performance Issues ............................................................................................... 42

Student Evaluation of Field Advisors ............................................................................................ 44

Student Concerns with the Advising Process ................................................................................ 44

Second-Year Placement Planning ................................................................................................. 45

Other Pertinent Issues .................................................................................................................. 45

6. Academic Advising ................................................................................ 47

4

7. Student Evaluation of Faculty Performance ........................................... 48

8. Academic and Professional Performance ............................................... 49

Essential Abilities and Attributes for Students at SSSW and in Professional Practice .................. 49

9. The Grading System .............................................................................. 54

Honors ........................................................................................................................................... 54

Credit ............................................................................................................................................. 54

No Credit ....................................................................................................................................... 54

Letter Grades ................................................................................................................................ 55

Incomplete .................................................................................................................................... 55

Attendance Requirements ............................................................................................................ 55

Grading Systems ........................................................................................................................... 56

10. Appeals and Reviews ........................................................................... 57

Grade Appeals Process .................................................................................................................. 57

Academic, Ethical, and Professional Conduct ............................................................................... 58

Academic and Field Competencies ............................................................................................... 59

Students Experiencing Difficulty Mastering Practice and/or Professional Competencies ........... 61

Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) Procedures ....................................................................... 61

Exceptions to the Performance Improvement Plan...................................................................... 61

Educational Review Committee (ERC) .......................................................................................... 62

ERC Procedure............................................................................................................................... 62

Possible Recommendations .......................................................................................................... 62

Dismissal Appeal Procedure .......................................................................................................... 63

11. Academic Standing .............................................................................. 64

Change of Status ........................................................................................................................... 64

Change from Full to Reduced Program Status .............................................................................. 64

Leave of Absence .......................................................................................................................... 64

Readmission .................................................................................................................................. 65

Withdrawal ................................................................................................................................... 65

12. Student Government and Committees ................................................ 66

Common Time ............................................................................................................................... 66

Student-Faculty Senate ................................................................................................................. 66

Committees with Student and Faculty Membership .................................................................... 66

Board of Student Representatives and Student Alliances ............................................................ 67

13. Communications ................................................................................. 68

Emergency Contact ....................................................................................................................... 68

Bulletin Boards .............................................................................................................................. 68

5

Telephones .................................................................................................................................... 68

Communication with Faculty ........................................................................................................ 69

Communication with Advisors ...................................................................................................... 69

Official Facebook Page .................................................................................................................. 69

Other Official Links ........................................................................................................................ 69

14. Post-Graduate Resources .................................................................... 70

Licensure Supports and Resources ............................................................................................... 70

Employment-Related Services ...................................................................................................... 71

15. Supports for Learning .......................................................................... 72

The Hunter College Libraries / The Social Work & Urban Public Health Library .......................... 72

Accessibility Services for Students ................................................................................................ 73

Computer Laboratory.................................................................................................................... 74

Audio Visual Resources ................................................................................................................. 74

The Silberman Writing Program ................................................................................................... 74

Hunter College Reading/Writing Center ....................................................................................... 74

Additional Student Supports ......................................................................................................... 75

16. Registration and Financial Aid ............................................................. 76

Records and Registration .............................................................................................................. 76

The Registration Process ............................................................................................................... 76

Registration ................................................................................................................................... 76

Registration Waitlist...................................................................................................................... 77

Tuition Payment ............................................................................................................................ 77

Refund Policy ................................................................................................................................ 77

Transfer, Waiver, and Prior Graduate Credits .............................................................................. 77

Instructions for Application to Transfer Credits ........................................................................... 77

Courses Subject to Waiver or Transfer ......................................................................................... 78

Financial Aid and Scholarships ...................................................................................................... 79

The New York Higher Education Services Corporation Loan ........................................................ 79

Eligibility for Student Loans .......................................................................................................... 79

Student Loan Deferments for Past Loans ..................................................................................... 79

17. Liability Insurance, Health and Counseling ............................................ 80

Liability Insurance ......................................................................................................................... 80

Health Services and Wellness Education ...................................................................................... 80

Health Insurance ........................................................................................................................... 80

Counseling Services ....................................................................................................................... 80

Hunter College Behavioral Response Team .................................................................................. 80

18. Facilities .................................................................................................. 81

The Building .................................................................................................................................. 81

Hours of Access ............................................................................................................................ 81

Restrooms ..................................................................................................................................... 81

6

Room Requests ............................................................................................................................. 81

Food Service .................................................................................................................................. 81

Smoking ......................................................................................................................................... 82

Building Operations ...................................................................................................................... 82

Fire Drills ....................................................................................................................................... 82

Fire/Emergency Procedures for Students with Disabilities .......................................................... 82

19. Finishing Up ............................................................................................ 83

Preparation for Graduation .......................................................................................................... 83

Appendix A: Required Courses and Program Models

Appendix B: Student Rights and College Policies

Appendix C: Faculty and Staff Directory

Appendix D: NASW Code of Ethics and Standards and Indicators of Cultural Competence

7

SILBERMAN SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK MISSION STATEMENT

The Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College (SSSW) educates and trains

outstanding social work professionals, who are lifelong learners engaged in

knowledgeable, ethical practice with communities locally and nationally. Guided by this

mission, we are uniquely committed to social work excellence in the public interest. Our

classroom curriculum, practicum experiences, and community-engaged partnerships are

focused on supporting persons, families, organizations, and communities, while

respecting the humanity of all individuals.

MSW PROGRAM MISSION STATEMENT

The Silberman School of Social Work MSW Program is committed to educating ethical,

culturally competent social workers to build community partnerships and strengthen

community capacity to achieve social justice in diverse, urban communities. This mission

promotes the creation, transformation, evaluation and assumption of leadership roles in

services across systems to meet the complex and unmet needs of underserved and

underrepresented populations through community-engaged education, intervention,

research, and advocacy.

MSW PROGRAM GOALS

To graduate excellently prepared and diverse social work practitioners for New

York City and other major urban areas who use a range of interventions with

individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities, and who operate

out of a strengths-based perspective and resiliency framework;

To emphasize urban contexts in the person-in-environment perspective,

particularly as it relates to preparation for employment as clinical practitioners,

community organizers and social services organization leaders;

To develop life-long learners able to respond innovatively to emerging practice

challenges in an ethical and research-informed manner;

To produce culturally competent social work practitioners and community

8

engaged scholarship and practice-based research;

To instill a commitment to social and economic justice that produces graduates

who skillfully and assertively advocate on behalf of clients and causes;

To educate students in partnership with New York’s communities, agencies, and

organizations to promote the expansion and dissemination of effective socially

just practice.

The School is fully accredited by the Council on Social Work Education.

9

1THE MSW PROGRAM

Overview

The Silberman School of Social Work at Hunter College (Silberman, SSW, SSSW, or

“the

School”)

adheres to the principle that social work education is based upon a common core

of practice values, skills, and knowledge that result in professional competency. The MSW

curriculum at the Silberman School of Social Work reflects a commitment to human rights,

cultural complexity, and social and economic justice.

The curriculum includes Human

Behavior and the Social Environment, Social Welfare Policy and Services, Social Work

Practice Methods, Social Work Research, the Field Practicum, and the Professional Seminar.

Students are required to take a year-long Social Work Practice Learning Lab and to select

one of three practice methods: Clinical Practice with Individuals, Families, and Small

Groups; Community Organizing, Planning and Development; or Organizational

Management and Leadership.

In addition, the SSSW requires Second-Year Full-Time, Time Frame II One Year

Residency, and Accelerated students to choose a specialization in a Field of Practice

(FOP). As a reflection of our commitment to social justice and human rights ,the nature of

the service systems where we do our work, and contemporary issues in social work

practice, the school has chosen the following four FOP specializations:

Aging

Child Welfare – Children, Youth and Families

Health and Mental Health (a sub-specialization in World of Work is available)

Global Social Work and Practice with Immigrants and Refugees

The School has strong ties to many social agencies which provide students with field

placements in a variety of practice areas. Qualified agency staff serve as accredited field

instructors. All field instructors must be SIFI certified. For detailed information on the field

practicum, please see the Silberman School of Social Work Field Education Manual.

Programs of Study—Pathways to the MSW Degree

The Silberman School of Social Work

offers several pathways leading to the Master of Social

Work (MSW)

degree.

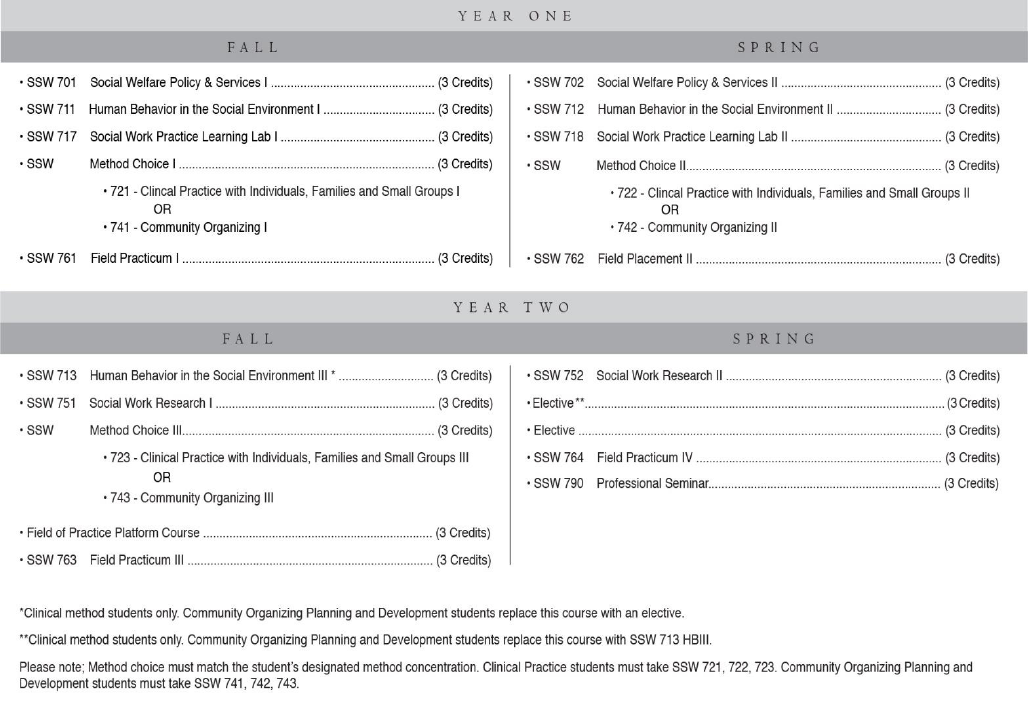

Two-Year, Full-Time Program (TYP)

The Two-Year, Full-Time Program (TYP) is designed for students who can devote

themselves to full-time academic and field study. Students are expected to attend

classes two

days a week with their pathway cohort, and to be in field placement three days a week during

standard business hours. Under this pathway, students complete the 60 academic credits

10

required for graduation in two years.

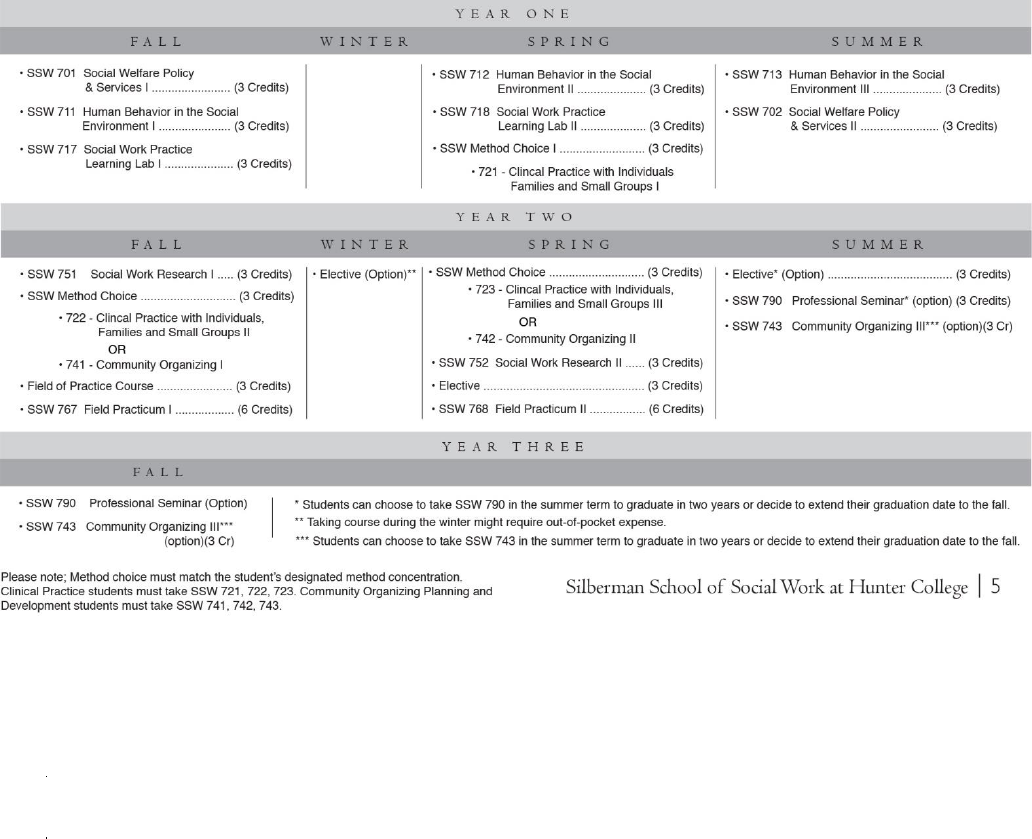

One-Year Residency Work-Study Program (OYR)

The One-Year Residency (OYR) Program provides opportunities for advanced social work

education to human services workers employed full-time within a social services agency in a

social-work-related role. Individuals are eligible for the OYR program if they have

completed a minimum of two years of post-baccalaureate full-time employment in a

recognized human service organization and if their current social welfare employer

agrees to provide them with a field internship, approved by the

school, during their second

year in the program. Students in the OYR program are permitted to take up to 30 hours of

course work on a part-time basis while

remaining in full-time employment. The OYR

Program is usually completed in two

and a half years of continuous study, but in some

instances may take longer. The field instruction requirement is completed during the second

year of the OYR Program, when students are enrolled in classes one day

per week and are in

field placement four days per week. The field practicum takes

place in the agency at which

the student is employed.

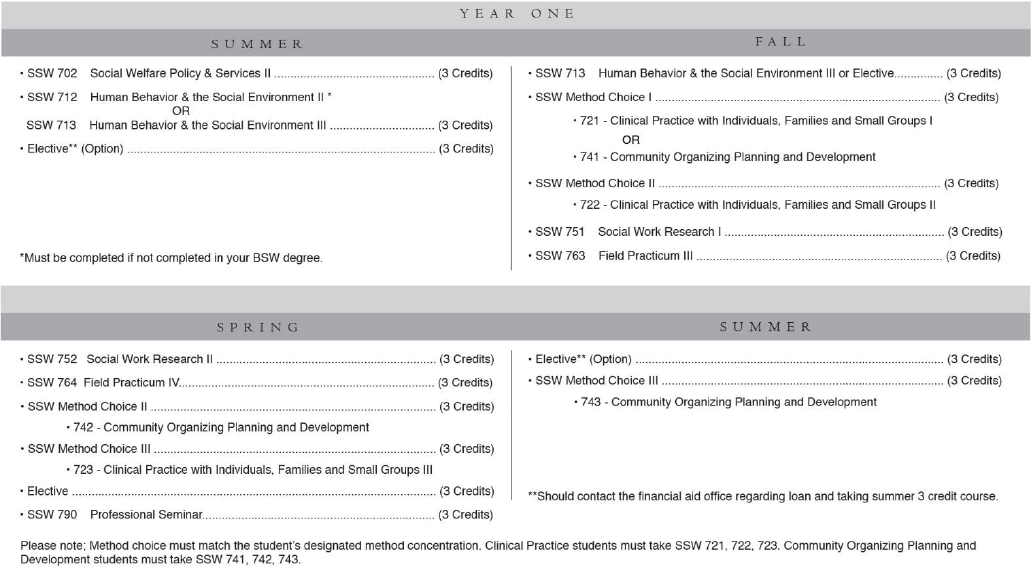

Advanced Standing Program

The Advanced Standing Program is an intensive program for a limited number of

outstanding students who have graduated from a Council on Social Work Education

(CSWE) accredited baccalaureate social work program. Applicants must have

received their

undergraduate degree within the last five years and must meet all other admission criteria for

acceptance into the graduate social work program at Hunter, including above-

average

performance in their undergraduate social work major. Applicants accepted into the program

will be waived from some courses required in the first year of the MSW program. Students

should review and confirm their individual registration requirements with an academic

advisor prior to the start of classes. Hunter's Advanced Standing Program typically begins in

the summer, followed by one academic year of full-time study, including a field placement

which takes place three days per week during standard business hours. Alternatively (and

depending on the chosen method), students may opt to begin their studies in the

fall and

continue through the

academic year and the following summer.

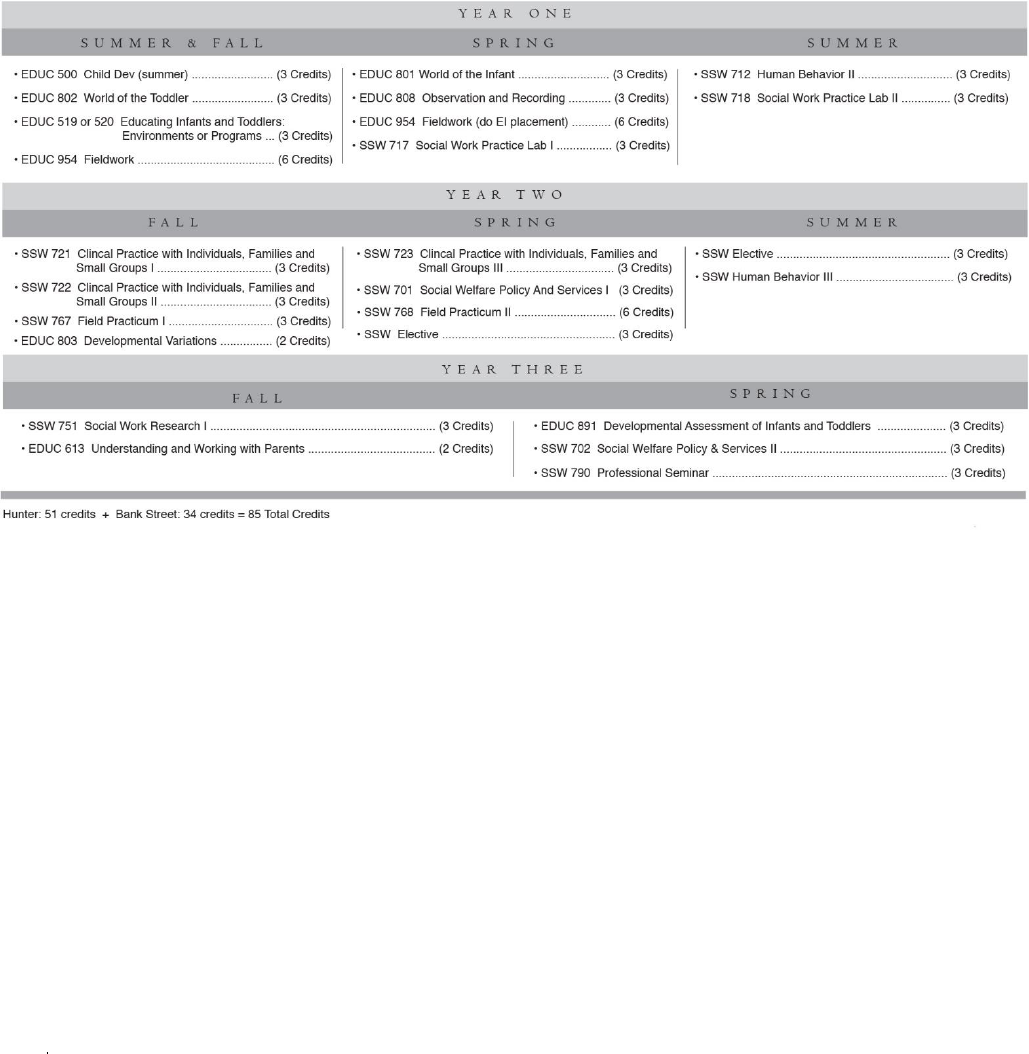

Dual Degree Program: School of Social Work and the Bank Street College of

Education

The Dual Degree Program is designed to prepare social workers to understand and work

with the special needs and vulnerabilities of children aged birth to three and their families.

The program prepares social workers for professional roles that combine both educational

and clinical skills. The curriculum design incorporates theoretical and practice aspects of

each degree into a cohesive educational and professional program. Applicants apply to

each institution separately. The MSW and the MS in Education degrees are awarded

simultaneously, upon completion of each program at the respective institution. The

program requirements satisfy the accreditation standards for each degree. In the first two

years of the program, students have an intensive experience at each institution. In the third

year, students move between both institutions to complete coursework. Both institutions

require a supervised field practicum. Applicants must meet all admission requirements of

the MSW program and are required to have experience in work with children. For the

Dual Degree Program, courses required at Bank Street total 36 academic credits; credits

11

required at Hunter total 51.

Accelerated Program

This program is designed for students ready to participate in an intensive, year-round

learning experience. It is a 60 credit program; as of this writing, the program is for

Clinical Practice majors only. Full-time students

matriculate

in January, are assigned field

placements, and complete their first-year requirements by the

end of the summer. They

start their third semester in the fall and graduate in the

following August. Students who

are already working in the human services field enter the

Accelerated OYR program

beginning with evening study in January through the summer

and complete their Time

Frame II studies in the following fall and spring. They are able

to graduate the following

December. Please note: Given the trajectory of the Accelerated Program, it is likely that

the total tuition cost will exceed that of the regular Two-Year Full-Time pathway.

All MSW students must complete their degree requirements within five years of

matriculation.

Change of Degree Pathway

All requests to change the chosen degree pathway – for both incoming and continuing

students – are referred to the Director of Enrollment Management. Requests will be

reviewed to confirm the student’s motivation for seeking the change, and to confirm that

the change is supported within the admissions criteria.

Students seeking to change their pathway to the One-Year Residency (OYR) must

demonstrate the requisite minimum of two [2] years’ full-time, direct social service

employment related to their practice method, along with the Agency Agreement

and letters of recommendation.

Students seeking to change to the Full-Time Two-Year pathway must be able to

confirm the time commitment of a full-time course schedule and weekday/daytime

field placement.

If Enrollment Management grants a student’s request for pathway change, the student will

meet with both the Department of Student Services and the Department of Field

Education to confirm and agree to their revised course trajectory. Depending on timing

and other case details, the student may need to repeat some courses. The Office of

Enrollment Management will confirm the student’s status change with the Departments of

Student Services and Field Education. The student is then assigned an academic advisor

for oversight and registration confirmation.

12

2CURRICULUM OF THE MSW DEGREE

PROGRAM

The Silberman School of Social Work curriculum is organized around professional

curriculum areas: Social Welfare Policy and Services; Human Behavior and the Social

Environment; Social Work Research; Social Work Practice Learning Laboratory; Practice

Methods (Clinical Practice with Individuals, Families, and Small Groups; Community

Organizing, Planning and Development; and Organizational Leadership and

Management); Field Practicum; Professional Seminar; and Field of Practice Platform

Course. All students must fulfill specific requirements in each of these professional

curriculum areas. Students must complete 60 credit hours to graduate with a master’s

degree in social work.

The School’s curriculum is also organized to ensure that all students attain competencies

and associated practice behaviors as required by the Council on Social Work Education.

Students will, in particular, gain advanced skills and practice behaviors associated with

their chosen Practice Method. The three charts below outline the core competencies and

associated practice behaviors which students in each Practice Method are expected to

attain.

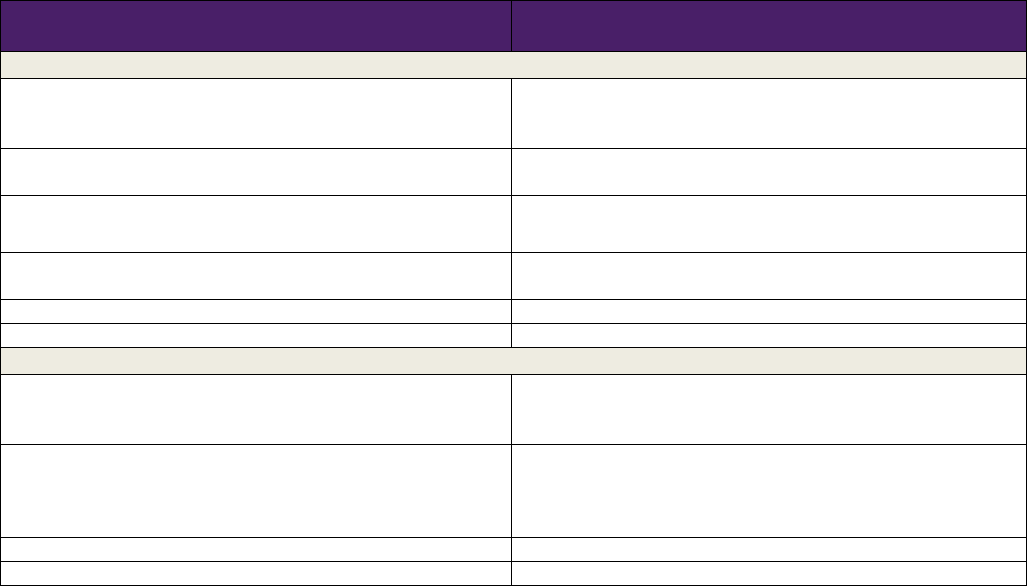

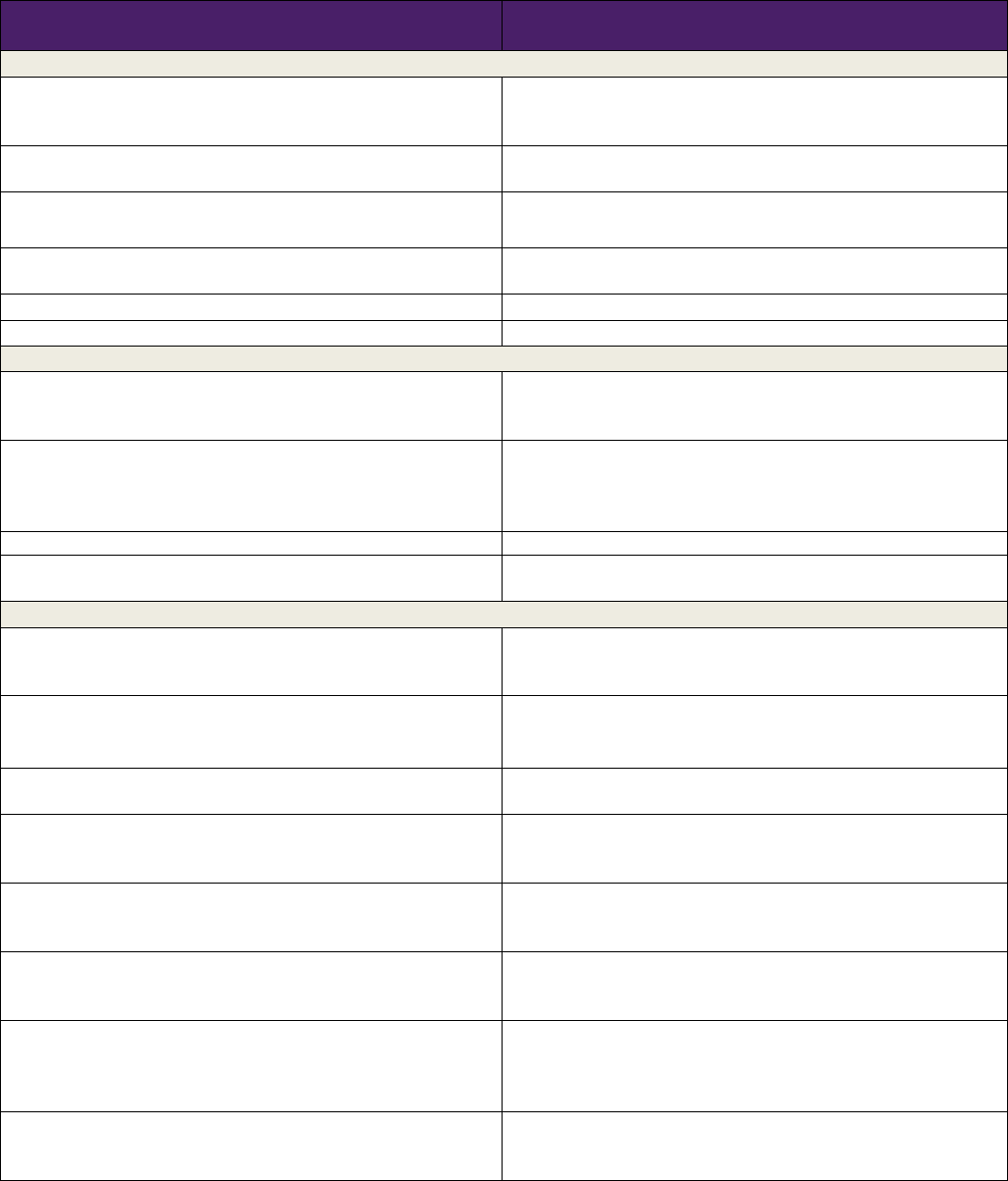

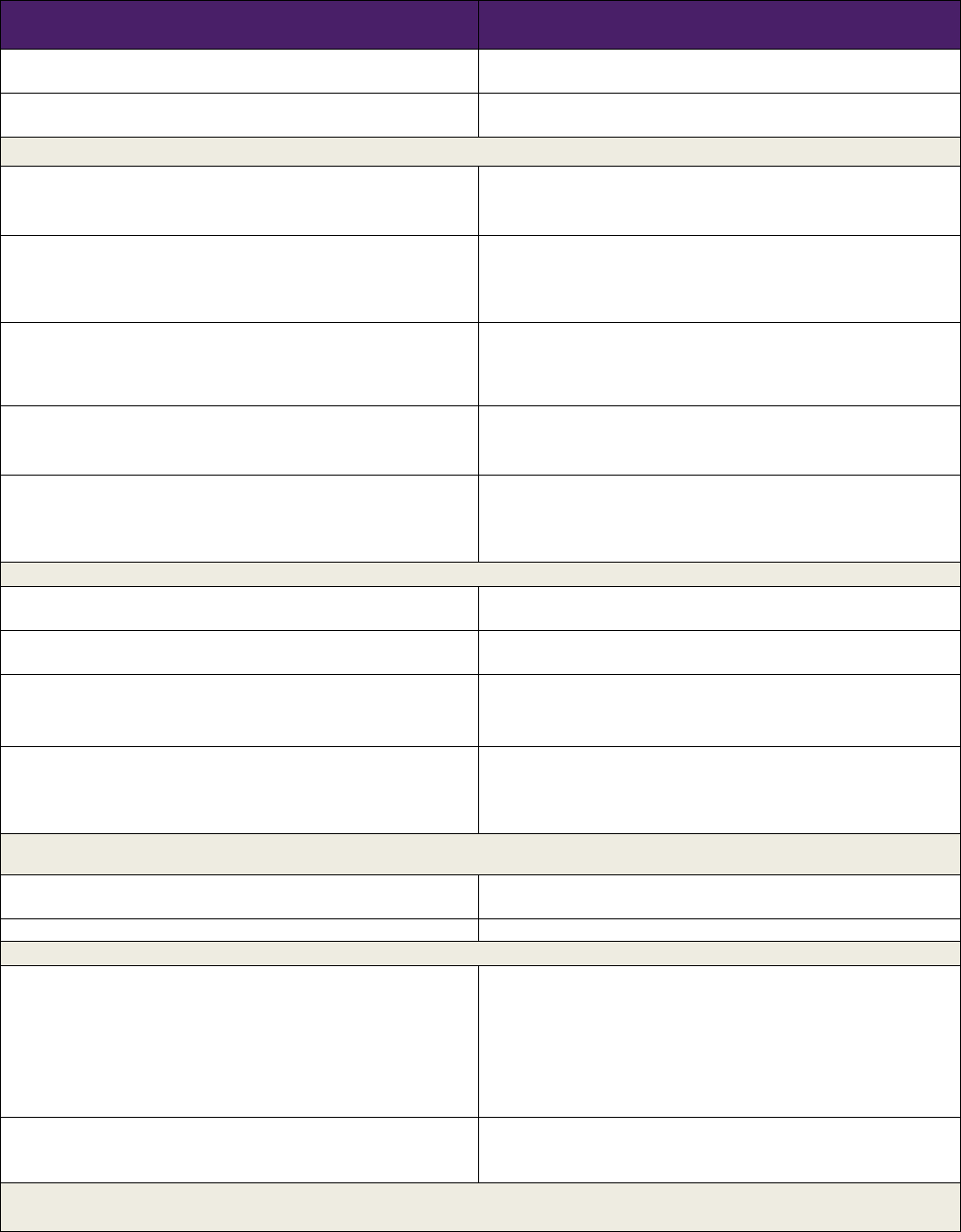

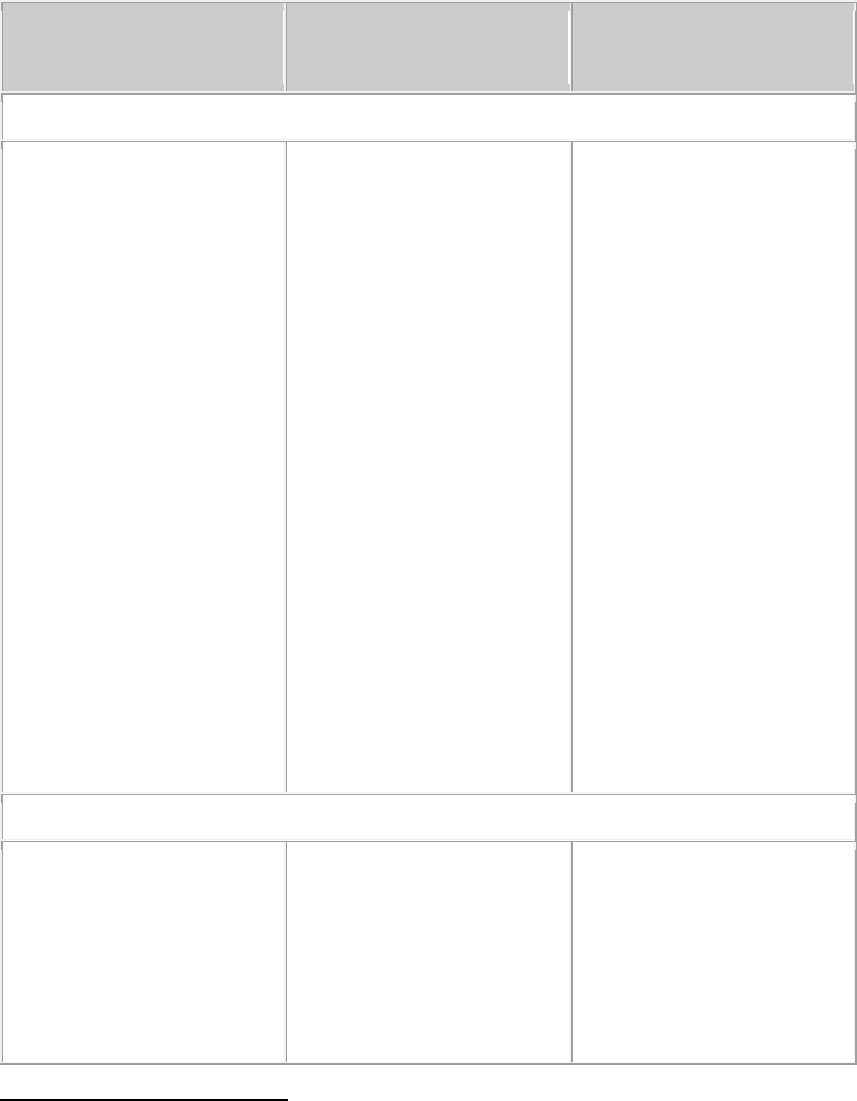

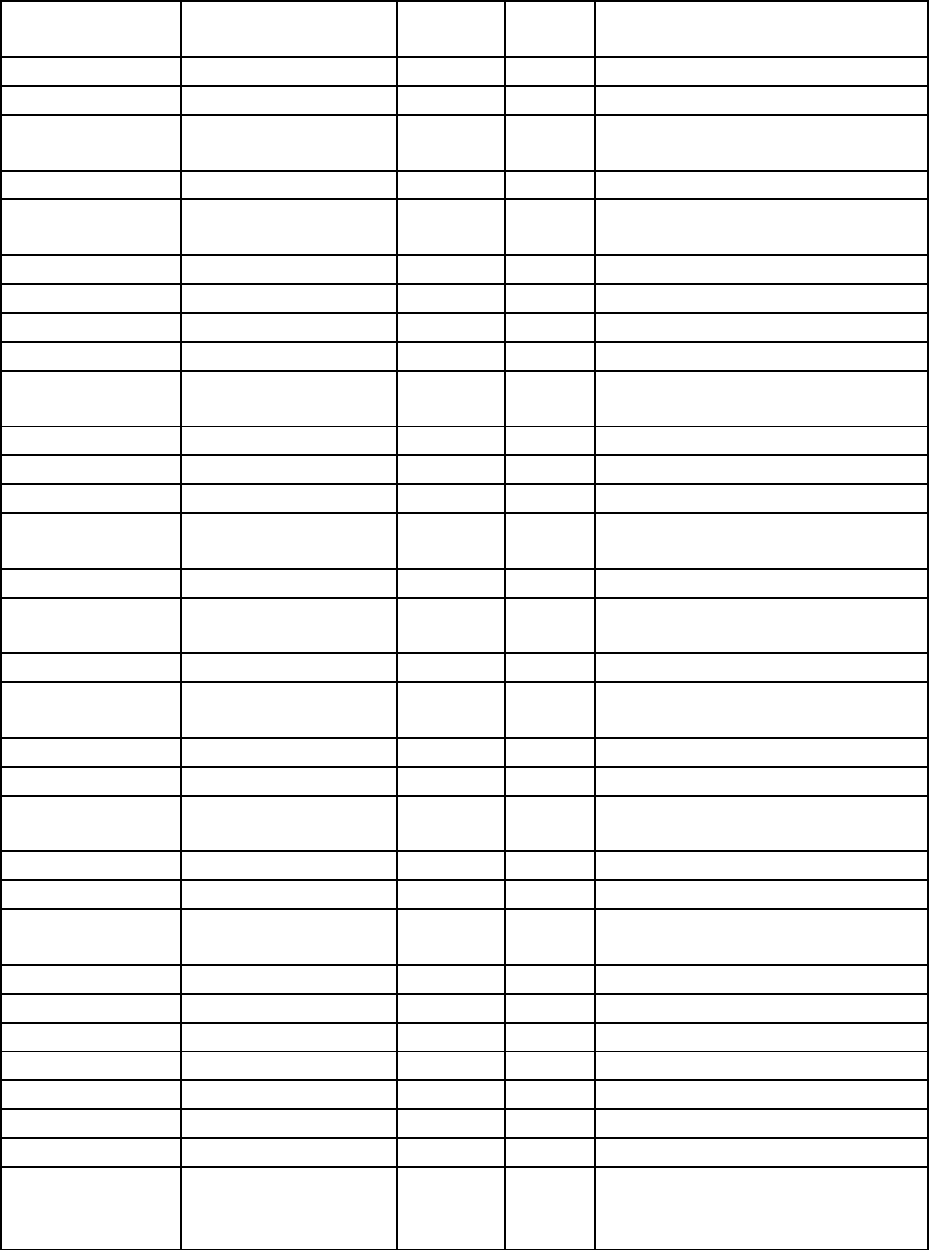

CSWE Core Competencies and Practice Behaviors: Clinical Practice with

Individuals, Families, and Small Groups

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

Identify as a professional social worker and conduct oneself accordingly (EP2.1.1)

PB 1: Advocate for client access to the services of

social work.

CPIFG APB 1: Demonstrate initiative and innovation in

advocating for client access to social work services

PB 2: Practice personal reflection and self-correction to

assure continual professional development.

PB 3: Attend to professional roles and boundaries.

PB 4: Demonstrate professional demeanor in behavior,

appearance, and communication.

PB 5: Engage in career-long learning.

PB 6: Use supervision and consultation.

Apply social work ethical principles to guide professional practice (EP 2.1.2)

PB 7: Recognize and manage personal values in a

way that allows professional values to guide practice.

CPIFG ABP 2: Differential use of self in engaging a

variety of client systems in professional helping

relationships

PB 8: Make ethical decisions by applying standards of

the National Association of Social Workers Code of

Ethics in Social Work, Statement of Principles (IFSW,

2004).

PB 9: Tolerate ambiguity in resolving ethical conflicts.

PB 10: Apply strategies of ethical reasoning to arrive at

13

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

principled decisions.

Apply critical thinking to inform and communicate professional judgments (EP 2.1.3)

PB 11: Distinguish, appraise, and integrate multiple

sources of knowledge, including research-based

knowledge and practice wisdom.

CPIFG APB 3: Collect and interpret information from

multiple sources of data

PB 12: Analyze models of assessment, prevention,

intervention, and evaluation.

CPIFG APB 4: Based on integration of multiple

sources of knowledge, propose new models of

assessment, prevention, intervention, and evaluation

CPIFG APB 5: Examine new models of assessment,

prevention, intervention, and evaluation

PB 13: Demonstrate effective oral and written

communication in working with individuals, families,

groups, organizations, communities, and colleagues.

CPIFG APB 6: Demonstrate capacity to effectively

communicate findings with a broader audience

FoP APB1: Differentially apply field-of- practice-specific

concepts and theories to social work methods

Engage diversity and difference in practice (EP 2.1.4)

PB 14: Recognize the extent to which a culture’s

structures and values may oppress, marginalize,

alienate, or create or enhance privilege and power

CPIFG APB 7: Formulate differential intervention

strategies in verbal and written form that reflect

recognition of client motivation, capacity, and

opportunity

PB 15: Gain sufficient self-awareness to eliminate the

influence of personal biases and values in working with

diverse groups

CPIFG APB 8: Demonstrate use of self in

implementing intervention models for specific case

parameters

PB 16: Recognize and communicate their

understanding of the importance of difference in

shaping life experiences

FoP APB2: Apply knowledge of anti-oppressive

practice as a lens for understanding the experiences of

those served in the specified field of practice

PB 17: View themselves as learners and engage those

with whom they work as informants

FoP APB3: Demonstrate cultural humility in learning

about and from those served in the specified field of

practice

FoP APB4: Demonstrate mindful social work practice

through self-awareness of one’s own worldview and

how that may interact with and impact upon work within

the specified field of practice

Advance human rights and social and economic justice (EP 2.1.5)

PB 18: Understand the forms and mechanisms of

oppression and discrimination

PB 19: Advocate for human rights and social and

economic justice

CPIFG APB 9: Critically assess how your CPIFG

practice advances social and economic justice

PB 20: Engage in practices that advance social and

economic justice

FoP APB5: Demonstrate working knowledge of

applicable laws, policies, and standards relevant to the

specified field of practice

FoP APB6: Apply knowledge of laws, policies, and

standards to engage in practices that advance human

rights, as well as social and economic justice within the

specified field of practice

Engage in research-informed practice and practice-informed research (EP 2.1.6)

PB 21: Use practice experience to inform scientific

inquiry.

CPIFG APB 10: Synthesize practice experience to

develop research agenda

PB 22: Use research evidence to inform practice

CPIFG APB 11: Conduct research to inform practice

Apply knowledge of human behavior and the social environment (EP 2.1.7)

PB 23: Use conceptual frameworks to guide the

CPIFG APB 12: Differentially apply conceptual

14

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

processes of assessment, intervention, and evaluation

frameworks to guide the processes of assessment,

intervention, and evaluation

PB 24: Critique and apply knowledge to understand

person and environment

Engage in policy practice to advance social and economic well-being and to deliver effective

social work services (EP 2.1.8)

PB 25: Analyze, formulate, and advocate for policies

that advance social well-being

CPIFG APB 13: Synthesize impact of CPIFG policy or

policies to advance social well-being

PB 26: Collaborate with colleagues and clients for

effective policy action

Respond to contexts that shape practice (EP 2.1.9)

PB 27: Continuously discover, appraise, and attend to

changing locales, populations, scientific and

technological developments, and emerging societal

trends to provide relevant services

CPIFG APB 14: Contribute to the knowledge base of

how context impacts practice

PB 28: Provide leadership in promoting sustainable

changes in service delivery and practice to improve the

quality of social services

FoP APB7: Assess and address the contextual factors

(e.g., social, economic, geographic, political,

environmental) that impact upon the lives and well-

being of those represented within the specified field of

practice

Engage with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10a)

PB 29: Substantively and affectively prepare for action

with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and

communities

CPIFG APB 15: Differentially engage diverse

individuals, families, and groups.

PB 30: Use empathy and other interpersonal skills

PB 31: Develop a mutually agreed-on focus of work

and desired outcomes

Assess individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10b)

PB 32: Collect, organize, and interpret client data

CPIFG APB 16: Conduct a differential assessment of

individuals and families through the integrated use of

theoretical concepts in examining the dynamic interplay

of bio-psycho-social variables

PB 33: Assess client strengths and limitations

CPIFG APB 17: Formulate a differential treatment plan

of individuals and families that is enhanced by clients’

input in examining their cognitive formulations of

personal constructs, schemas and world views

PB 34: Develop mutually agreed-on intervention goals

and objectives

PB 35: Select appropriate intervention strategies

Intervene with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10c)

PB 36: Initiate actions to achieve organizational goals

CPIFG APB 18: Identify, critically evaluate, select,

apply evidence-based change strategies across the

stages of Clinical Practice with Individuals, Families,

and Groups

PB 37: Implement prevention interventions that

enhance client capacities

CPIFG APB 19: Adapt change strategies and

treatment applications across stages of Clinical

Practice with Individuals, Families, and Groups

PB 38: Help clients resolve problems

CPIFG APB 20: Select, integrate and apply appropriate

interventions from various theoretical models in

practice with individuals and families of diverse

background

PB 39: Negotiate, mediate, and advocate for clients

PB 40: Facilitate transitions and endings.

15

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

Evaluate individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10d)

PB 41: Social workers critically analyze, monitor, and

evaluate interventions.

CPIFG APB 21: Differentially evaluates practice

effectiveness and modifies interventions accordingly or

brings work to closure.

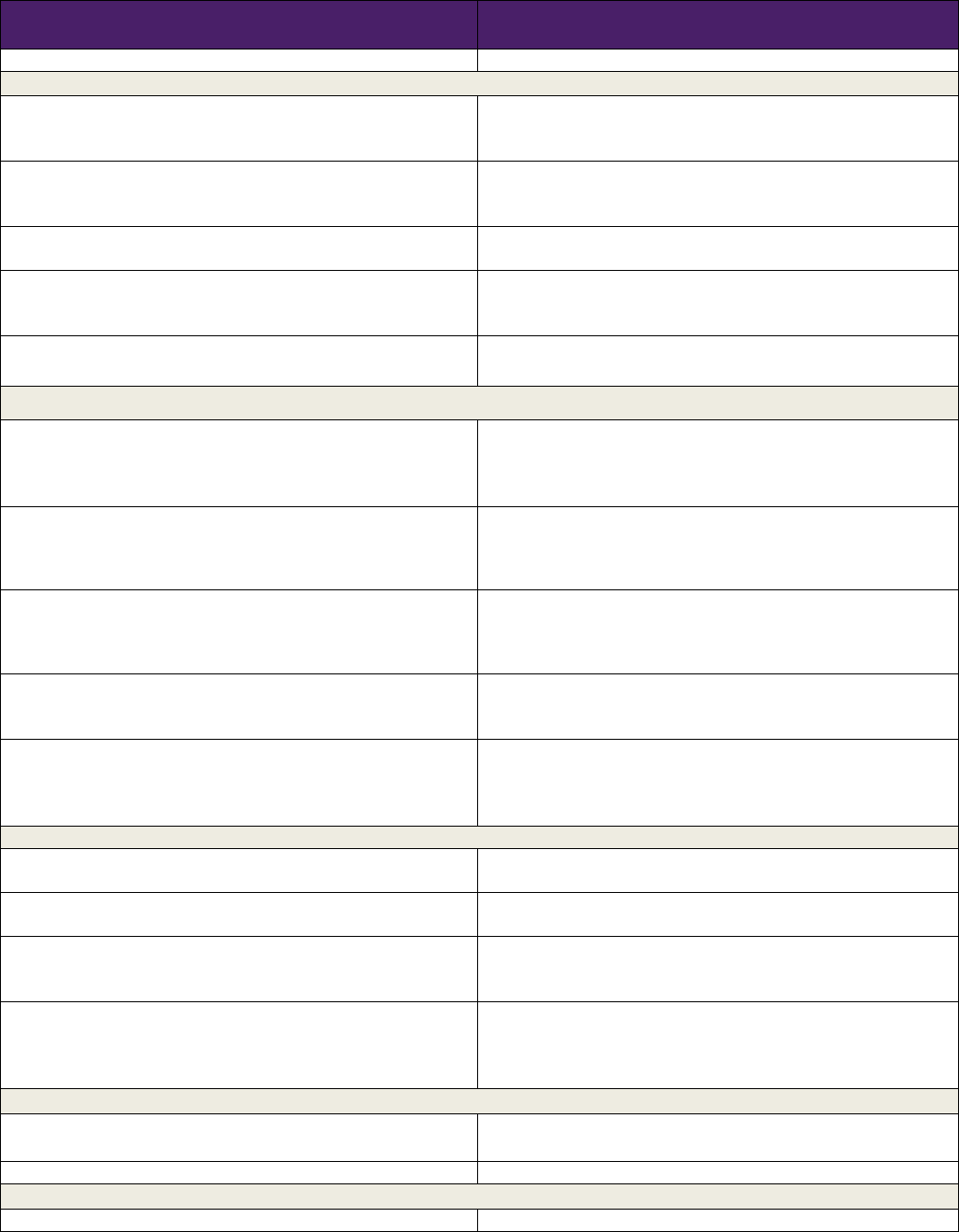

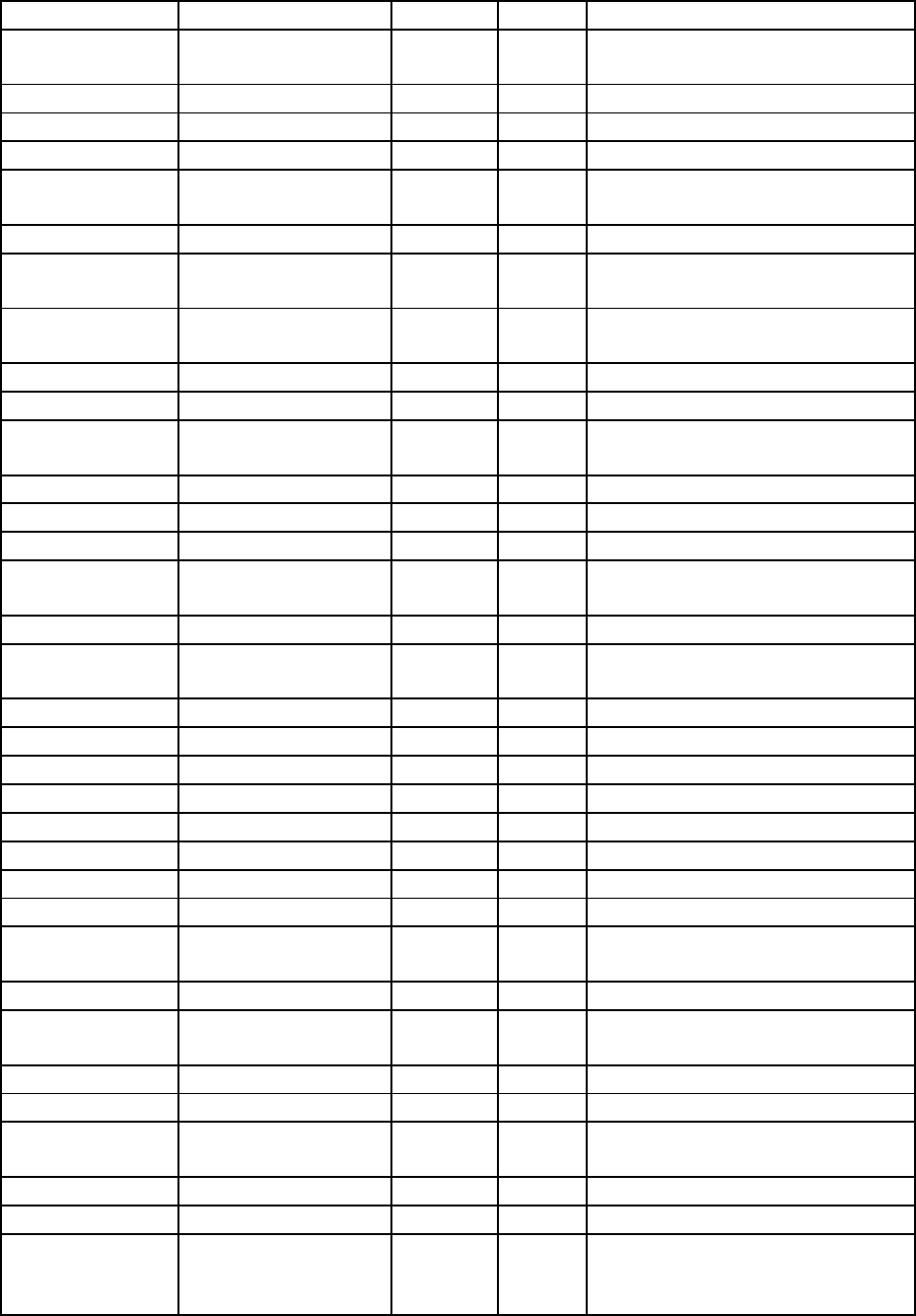

CSWE Core Competencies and Practice Behaviors: Community Organizing,

Planning, and Development

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

Identify as a professional social worker and conduct oneself accordingly (EP2.1.1)

PB 1: Advocate for client access to the services of

social work.

COPD APB 1: Demonstrate flexibility in assessing

tactical choices and community members’ roles and

responsibilities

PB 2: Practice personal reflection and self-correction to

assure continual professional development.

COPD APB 2: Further enhance comfort in organizing

role and those roles of community leaders in the

process of co-creation of democratic strategy

formation.

PB 3: Attend to professional roles and boundaries.

PB 4: Demonstrate professional demeanor in behavior,

appearance, and communication.

PB 5: Engage in career-long learning.

PB 6: Use supervision and consultation.

Apply social work ethical principles to guide professional practice (EP 2.1.2)

PB 7: Recognize and manage personal values in a

way that allows professional values to guide practice.

COPD ABP 3: Understand and act upon core personal

values so that become operational and concrete

PB 8: Make ethical decisions by applying standards of

the National Association of Social Workers Code of

Ethics in Social Work, Statement of Principles (IFSW,

2004).

COPD ABP 4: Help other understand and work with

the dilemmas between means and ends;

PB 9: Tolerate ambiguity in resolving ethical conflicts.

COPD ABP 5: Apply ethical standards, ethical laws,

and ethical reasoning in promoting human rights and

social justice in the assessment, intervention, and

evaluation of organizational and community practice.

PB 10: Apply strategies of ethical reasoning to arrive at

principled decisions.

Apply critical thinking to inform and communicate professional judgments (EP 2.1.3)

PB 11: Distinguish, appraise, and integrate multiple

sources of knowledge, including research-based

knowledge and practice wisdom.

COPD APB 6: Use logic, critical thinking, creativity,

and synthesis of multiple frameworks and sources of

information to make professional judgments regarding

your own planning style and the style of your field

placement agency.

PB 12: Analyze models of assessment, prevention,

intervention, and evaluation.

COPD APB 7: Collect and interpret information from

multiple sources of data.

PB 13: Demonstrate effective oral and written

communication in working with individuals, families,

groups, organizations, communities, and colleagues.

COPD APB 8: Based on integration of multiple sources

of knowledge, propose new models of assessment,

prevention, intervention, and evaluation

COPD APB 9: Examine new models of assessment,

16

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

prevention, intervention, and evaluation

COPD APB 10: Demonstrate capacity to effectively

communicate findings with a broader audience

FoP APB1: Differentially apply field-of- practice-specific

concepts and theories to social work methods

Engage diversity and difference in practice (EP 2.1.4)

PB 14: Recognize the extent to which a culture’s

structures and values may oppress, marginalize,

alienate, or create or enhance privilege and power.

COPD APB 11: Engage with and ensure participation

of diverse and marginalized community and

organizational constituents by identifying and

accommodating multilingual and non-literate needs,

gender power dynamics, and access for disabilities in

assessing, planning, and implementing.

PB 15: Gain sufficient self-awareness to eliminate the

influence of personal biases and values in working with

diverse groups.

FoP APB2: Apply knowledge of anti-oppressive

practice as a lens for understanding the experiences of

those served in the specified field of practice

PB 16: Recognize and communicate their

understanding of the importance of difference in

shaping life experiences.

FoP APB3: Demonstrate cultural humility in learning

about and from those served in the specified field of

practice

PB 17: View themselves as learners and engage those

with whom they work as informants.

FoP APB4: Demonstrate mindful social work practice

through self-awareness of one’s own worldview and

how that may interact with and impact upon work within

the specified field of practice

Advance human rights and social and economic justice (EP 2.1.5)

PB 18: Understand the forms and mechanisms of

oppression and discrimination.

PB 19: Advocate for human rights and social and

economic justice.

COPD APB 12: Critically assess how one’s COPD

practice advances social and economic justice.

PB 20: Engage in practices that advance social and

economic justice.

FoP APB5: Demonstrate working knowledge of

applicable laws, policies, and standards relevant to the

specified field of practice

FoP APB6: Apply knowledge of laws, policies, and

standards to engage in practices that advance human

rights, as well as social and economic justice within the

specified field of practice

Engage in research-informed practice and practice-informed research (EP 2.1.6)

PB 21: Use practice experience to inform scientific

inquiry.

COPD APB 13: Utilize theories of community and

organizational behavior and evidence-informed

research to develop, implement, and evaluate a plan of

action for community or organizational intervention in

your field placement agency (or other setting).

PB 22: Use research evidence to inform practice.

COPD APB 14: Synthesize practice experience to

develop research agenda.

COPD APB 15: Conduct research to inform practice

Apply knowledge of human behavior and the social environment (EP 2.1.7)

PB 23: Use conceptual frameworks to guide the

processes of assessment, intervention, and evaluation.

COPD APB 16: Differentially apply conceptual

frameworks to guide the processes of assessment,

intervention, and evaluation.

PB 24: Critique and apply knowledge to understand

person and environment.

Engage in policy practice to advance social and economic well-being and to deliver effective

social work services (EP 2.1.8)

PB 25: Analyze, formulate, and advocate for policies

COPD APB 17: Synthesize impact of COPD policy on

17

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

that advance social well-being.

practice to advance social well-being

PB 26: Collaborate with colleagues and clients for

effective policy action.

Respond to contexts that shape practice (EP 2.1.9)

PB 27: Continuously discover, appraise, and attend to

changing locales, populations, scientific and

technological developments, and emerging societal

trends to provide relevant services.

COPD APB 18: Contribute to knowledge base of how

context impacts COPD practice

PB 28: Provide leadership in promoting sustainable

changes in service delivery and practice to improve the

quality of social services.

FoP APB7: Assess and address the contextual factors

(e.g., social, economic, geographic, political,

environmental) that impact upon the lives and well-

being of those represented within the specified field of

practice

Engage with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10a)

PB 29: Substantively and affectively prepare for action

with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and

communities.

COPD APB 19: Model leadership behaviors and beliefs

in others’ capacities to lead

COPD APB 20: Differentially engage diverse

individuals, families, and groups.

PB 30: Use empathy and other interpersonal skills.

COPD APB 21: Develop capacities to discern and

develop leadership with those who have less power

and privilege

PB 31: Develop a mutually agreed-on focus of work

and desired outcomes.

COPD APB 22: Engage with coalitions, their

constituencies, and the organizations that comprise

them to assess and analyze their capacities, strengths,

strategies/tactics, needs, and outcomes, as well as to

make recommendations to them for appropriate future

actions.

Assess individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10b)

PB 32: Collect, organize, and interpret client data.

COPD APB 23: Demonstrate ‘respect and challenge”

in decision-making in community groups

PB 33: Assess client strengths and limitations.

COPD APB 24: Practice ‘where the people are at plus

one.”

PB 34: Develop mutually agreed-on intervention goals

and objectives.

PB 35: Select appropriate intervention strategies.

Intervene with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10c)

PB 36: Initiate actions to achieve organizational goals.

COPD APB 25: Create agendas that are of interest to

and involve all levels of membership;

PB 37: Implement prevention interventions that

enhance client capacities.

COPD APB 26: Run meetings as arenas for

democratic leadership development;

PB 38: Help clients resolve problems

PB 39: Negotiate, mediate, and advocate for clients.

PB 40: Facilitate transitions and endings.

Evaluate individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10d)

PB 41: Social workers critically analyze, monitor, and

evaluate interventions.

COPD APB 27: Differentially evaluates practice

effectiveness and modifies interventions accordingly or

brings work to closure.

18

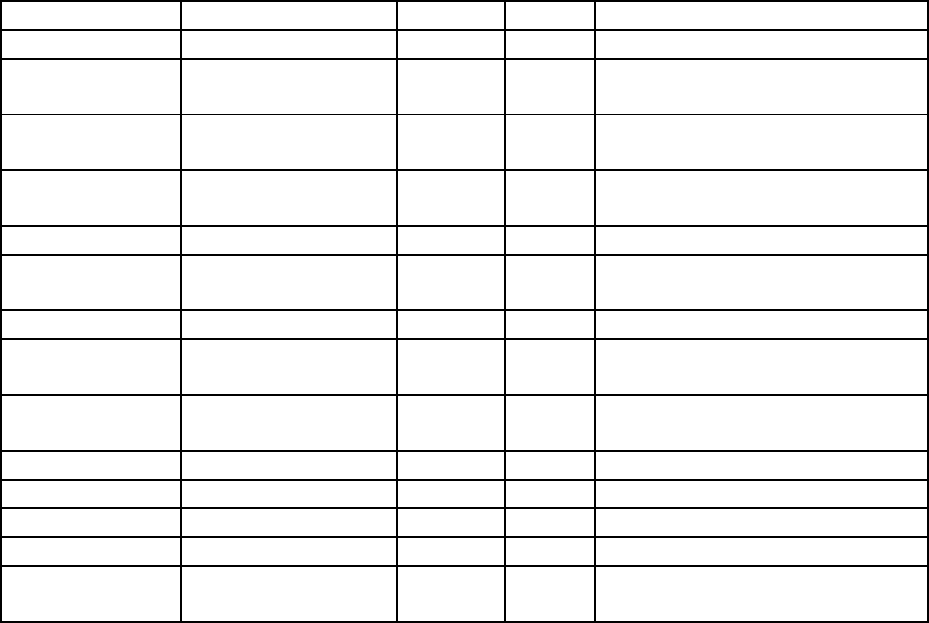

CSWE Core Competencies and Practice Behaviors: Organizational

Management and Leadership

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

Identify as a professional social worker and conduct oneself accordingly (EP 2.1.1)

PB 1: Advocate for client access to the services of

social work

OML APB 1: Demonstrate initiative and innovation in

advocating for client access to the services of social

work

PB 2: Practice personal reflection and self-correction to

assure continual professional development

PB 3: Attend to professional roles and boundaries

PB 4: Demonstrate professional demeanor in behavior,

appearance, and communication

PB 5: Engage in career-long learning

PB 6: Use supervision and consultation

Apply social work ethical principles to guide professional practice (EP 2.1.2)

PB 7: Recognize and manage personal values in a

way that allows professional values to guide practice.

OML APB 2: Apply differential use of self in engaging

organizational stakeholders in professional helping

relationships

PB 8: Make ethical decisions by applying standards of

the National Association of Social Workers Code of

Ethics in Social Work, Statement of Principles (IFSW,

2004).

PB 9: Tolerate ambiguity in resolving ethical conflicts.

PB 10: Apply strategies of ethical reasoning to arrive at

principled decisions.

Apply critical thinking to inform and communicate professional judgments (EP 2.1.3)

PB 11: Distinguish, appraise, and integrate multiple

sources of knowledge, including research-based

knowledge and practice wisdom.

OML APB 3: Collect and interpret information from

multiple sources of data

PB 12: Analyze models of assessment, prevention,

intervention, and evaluation.

OML APB 4: Based on integration of multiple sources

of knowledge, propose new models of assessment,

prevention, intervention, and evaluation

OML APB 5: Examine new models of assessment,

prevention, intervention, and evaluation

PB 13: Demonstrate effective oral and written

communication in working with individuals, families,

groups, organizations, communities, and colleagues.

OML APB 6: Demonstrate capacity to effectively

communicate findings with a broader audience

OML APB 7: Apply critical and strategic thinking to

decisions concerning the financial management of

social service organizations and programs

OML APB 8: Demonstrate knowledge about how a

board of directors and an executive can create and/or

operate a mission driven organization

OML APB 9: Apply knowledge of organizations to

critically strategize organizational change, including the

ability of organizational actors to achieve the change

they desire

OML APB 10: Apply knowledge of organizational

lifecycles from one or more of the perspectives on this

addressed in the class, and how the lifecycles of

19

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

organizations influence managing human service

organizations, especially strategically.

FoP APB1: Differentially apply field-of- practice-specific

concepts and theories to social work methods

Engage diversity and difference in practice (EP 2.1.4)

PB 14: Recognize the extent to which a culture’s

structures and values may oppress, marginalize,

alienate, or create or enhance privilege and power.

OML APB 11: Formulate differential interventions that

engage multiple stakeholders

OML APB 12: Apply skills and knowledge of managing

issues of diversity and difference in social service

organizations, the environments in which they are

embedded, and among organizational stakeholders.

PB 15: Gain sufficient self-awareness to eliminate the

influence of personal biases and values in working with

diverse groups.

FoP APB2: Apply knowledge of anti-oppressive

practice as a lens for understanding the experiences of

those served in the specified field of practice

PB 16: Recognize and communicate their

understanding of the importance of difference in

shaping life experiences.

FoP APB3: Demonstrate cultural humility in learning

about and from those served in the specified field of

practice

PB 17: view themselves as learners and engage those

with whom they work as informants.

FoP APB4: Demonstrate mindful social work practice

through self-awareness of one’s own worldview and

how that may interact with and impact upon work within

the specified field of practice

Advance human rights and social and economic justice (EP 2.1.5)

PB 18: Understand the forms and mechanisms of

oppression and discrimination.

PB 19: Advocate for human rights and social and

economic justice.

OML APB 13: Critically assess how your OML practice

advances social and economic justice

PB 20: Engage in practices that advance social and

economic justice.

FoP APB5: Demonstrate working knowledge of

applicable laws, policies, and standards relevant to the

specified field of practice

FoP APB6: Apply knowledge of laws, policies, and

standards to engage in practices that advance human

rights, as well as social and economic justice within the

specified field of practice

Engage in research-informed practice and practice-informed research (EP 2.1.6)

PB 21: Use practice experience to inform scientific

inquiry.

OML APB 14: Synthesize practice experience to

develop research agenda

PB 22: Use research evidence to inform practice.

OML APB 15: Conduct research to inform practice

Apply knowledge of human behavior and the social environment (EP 2.1.7)

PB 23: Use conceptual frameworks to guide the

processes of assessment, intervention, and evaluation.

OML APB 16: Apply the knowledge of human behavior

and the social environment to the development of

resources for social service organizations and

programs. Resource development is a dynamic

interpersonal process requiring knowledge of human

behavior and complex organizational and inter-

organizational environments.

PB 24: Critique and apply knowledge to understand

person and environment.

OML APB 17: Demonstrate awareness and

understanding of how organizational change affects

various stakeholder constituencies of the organization.

Engage in policy practice to advance social and economic well-being and to deliver effective

social work services (EP 2.1.8)

20

Competencies and Foundation-Level

Practice Behaviors

Competencies and Advanced-Level

Practice Behaviors

PB 25: Analyze, formulate, and advocate for policies

that advance social well-being.

OML APB 18: Synthesize impact of OML policy on

practice to advance social well-being

PB 26: Collaborate with colleagues and clients for

effective policy action.

Respond to contexts that shape practice (EP 2.1.9)

PB 27: Continuously discover, appraise, and attend to

changing locales, populations, scientific and

technological developments, and emerging societal

trends to provide relevant services.

OML APB 19: Apply knowledge and skills of how

technology affects the organization, its employees, and

its service users

PB 28: Provide leadership in promoting sustainable

changes in service delivery and practice to improve the

quality of social services.

OML APB 20: Demonstrate knowledge about the

planning, design, and implementation of human

services and systems.

FoP APB7: Assess and address the contextual factors

(e.g., social, economic, geographic, political,

environmental) that impact upon the lives and well-

being of those represented within the specified field of

practice

Engage with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10a)

PB 29: Substantively and affectively prepare for action

with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and

communities.

OML APB 21: Develop capacities to discern and

develop leadership with those who have less power

and privilege

PB 30: Use empathy and other interpersonal skills.

PB 31: Develop a mutually agreed-on focus of work

and desired outcomes.

Assess individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10b)

PB 32: Collect, organize, and interpret client data.

OML APB 22: Demonstrate knowledge about how to

assess the processes used to determine new

employee-organization fit and the other tasks of human

resource management

PB 33: Assess client strengths and limitations.

PB 34: Develop mutually agreed-on intervention goals

and objectives.

PB 35: Select appropriate intervention strategies.

Intervene with individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10c)

PB 36: Initiate actions to achieve organizational goals.

PB 37: Implement prevention interventions that

enhance client capacities.

OML APB 23: Apply skills and knowledge of individual

behavior in groups, group behavior, and organizational

dynamics

PB 38: Help clients resolve problems

PB 39: Negotiate, mediate, and advocate for clients.

PB 40: Facilitate transitions and endings.

Evaluate individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities (EP 2.1.10d)

PB 41: Social workers critically analyze, monitor, and

evaluate interventions.

OML APB 24: Differentially evaluates practice

effectiveness and modifies interventions accordingly or

brings work to closure.

21

Method Concentration

Students select their Method Concentration prior to admission. OYR students are

generally admitted to the method in which they have practice experience. Students must

take three sequential method concentration courses that start in their first semester of

enrollment and are concurrent with a supervised field practicum in that

method. Practice

method courses must be taken concurrently with field placement. Please note that students

cannot register for method classes different from their chosen method. OYR students must take

two semesters of method concentration courses concurrently

with the field practicum and

a third methods course either prior to or after the practicum, depending on their method.

Change of Method Concentration

Once a student is enrolled and placed, changes in one’s method concentration can be

considered only after consultation with the field advisor, the Director of

Student Services

and the Director of Field Education. Approval must be obtained from the

chairpersons

of the method areas one is leaving and entering, with final approval typically granted by

the Associate Dean for Faculty and Academic Affairs. Since field placement assignments

are provided to maximize practice in a method concentration, a change of method

concentration may require a change of field placement as well as an extension of time in

field, and may therefore cause a disruption in a student’s program of study.

For admitted students prior to starting classes at Silberman

Students are referred to Enrollment Management to reassess the initial application and

acceptance criteria and determine the suitability of granting the request. If the request is

approved, Enrollment Management will notify the Field Education Department and the

Department of Student Services.

For continuing students

Requests are reviewed by the Field Education Department and the Department of

Student Services. Factors considered in the initial review include where the student is in

their trajectory and whether their internship can support the change in method. The

student is then referred to the Chairs of both the outgoing and incoming methods for

discussion. If the Chairs sign off on the request, the student is referred to the Associate

Dean for Faculty and Academic Affairs for final approval.. If the request is officially

approved, the student meets with the Field Education Department and the Department

of Student Services to confirm their revised academic plan. The student is then assigned

an academic advisor for oversight and registration.

Additional Program Requirements

Some of the required courses are sequential and are scheduled accordingly (e.g., SSW 717-

718, The Social Work Practice Learning Lab; 711-713, Human Behavior and the Social

Environment; Research I & II).

The Field Practicum is sequential and constitutes a year-long educational

experience. When a student is unable to successfully pass both semesters, it

is usually necessary to begin the sequence again. If a student has passed the

first semester but cannot complete the second semester, a repeat of the

entire

year is usually necessary. In such situations, students must meet with the

Director of Field Education and the Director of Student Services to develop an

22

appropriate plan.

Students should consult with published and e-mailed registration materials

as

well as with an academic advisor before selecting courses.

Please review Appendix A for course Requirements.

In addition to coursework, students are required to complete the Mandated

Reporter training and the licensure information training - both are available

online. The Mandated Reporter training workshop is required for eligibility to

take

the New York State Exam to become a Licensed Master Social Worker

(LMSW).

Students are required to take SSW 751 and 752, Social Work Research. If the

research they wish to undertake in their course requires the participation of

human subjects (e.g., interviews,

systematic observation, or self-

administered questionnaires), students must

first obtain approval from the

classroom instructor. Such research projects will likely require prior

approval of Hunter College's Committee for the Protection of Human

Subjects from Research Risks. The research sequence will be taken

concurrently with the field practicum. Please note: Students must continue in

the same section from SSW 751 into SSW 752.

In their final semester, students enroll in SSW 790, the Professional Seminar.

In this course, students have the opportunity to integrate their learning and

write a paper or prepare a project whose central focus is a social work issue

of particular interest. The paper or project requires students to

utilize

research findings, scholarly works, and professional experience to

consider

how the current state of knowledge, current thinking on policy, and current

approaches to practice affect the resolution of an appropriate issue.

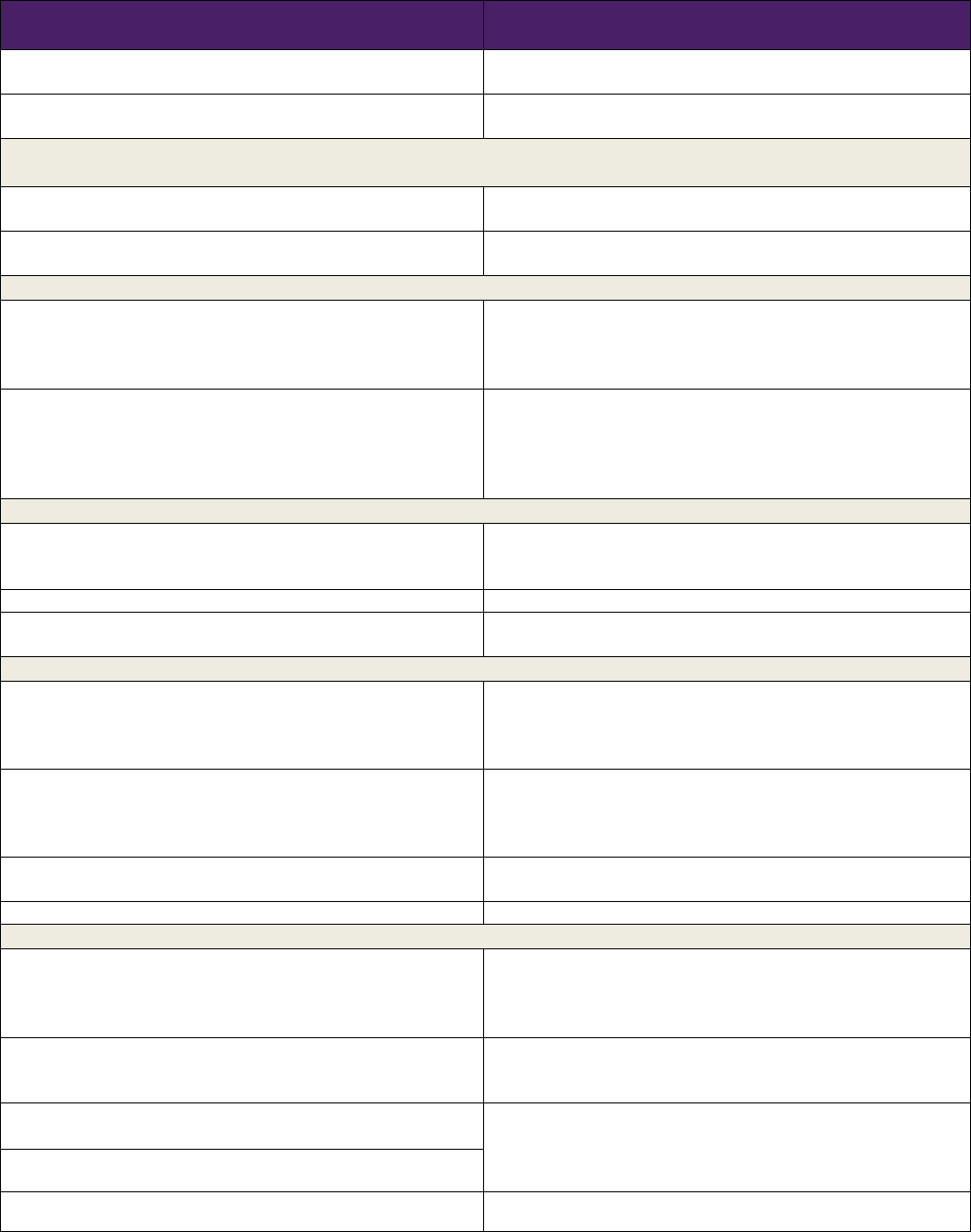

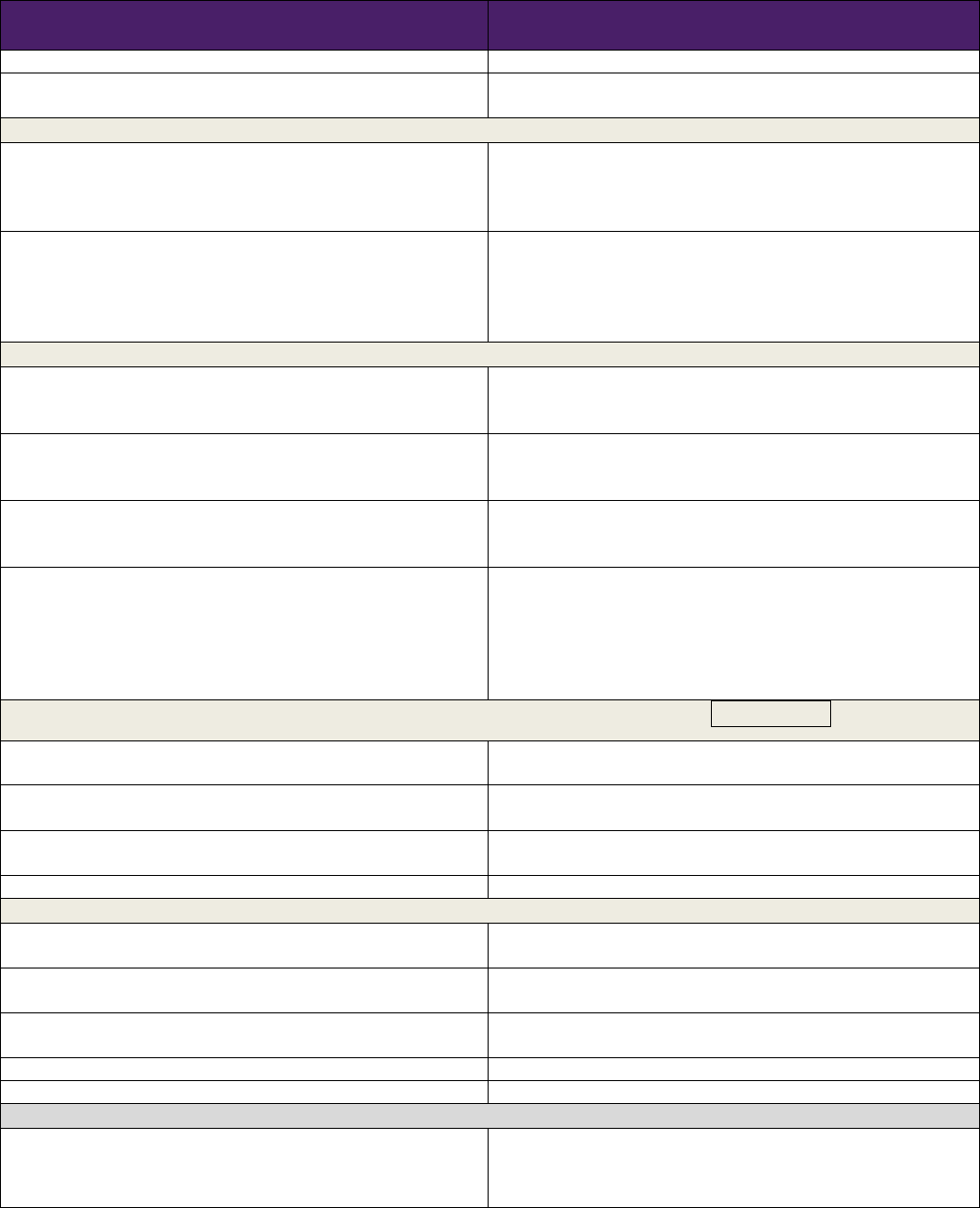

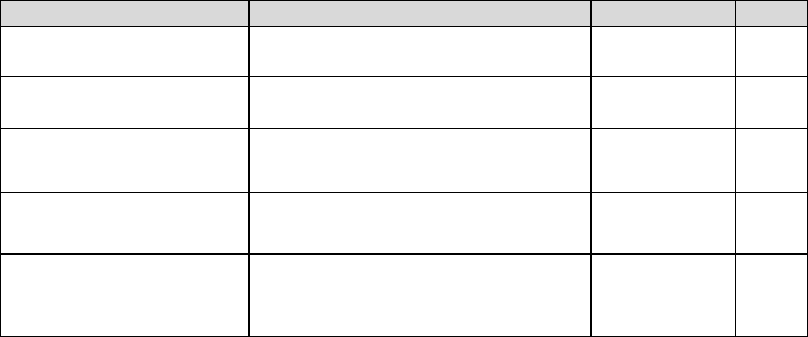

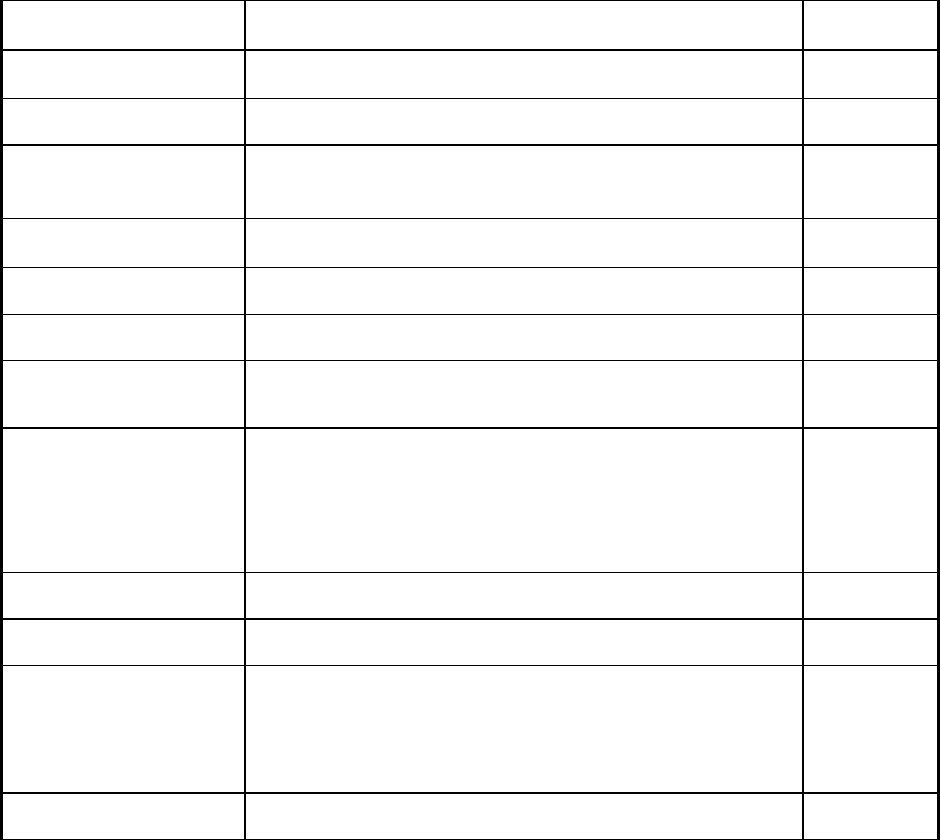

Chairs

Professional Curriculum Areas

Phone (212)

Room

Dr. Mimi Abramovitz

Social Welfare Policy and Services

396-7535

432

Dr. Ilze Earner

Human Behavior & the Social Environment

396-7565

705

Dr. Willie Tolliver

Dr. Robyn Brown-Manning

Social Work Practice Learning Laboratory

396-7523

396-7782

409

722

Dr. Samuel Aymer

Clinical Practice with Individuals, Families and Small

Groups

396-7555

456

Dr. Stephen Burghardt

Community Organization, Planning,

and Development (COPD)

396-7524

410

Dr. James Mandiberg

Organizational Management and Leadership

396-7525

422

Dr. Bernadette Hadden

Research

396-7545

446

Ms. Kanako Okuda, LCSW

Field Education

396-7571

302

Dr. Patricia Dempsey

BSW Program

396-7532

429

23

Attendance Requirements

An integral part of professional comportment is punctuality and dependability. Given

this, students should make every effort to attend every course session for all courses in

which they are enrolled. We realize that absences are at times unavoidable. Students

should review course syllabi to confirm the attendance requirements and policies for each

of their courses prior to the start of the semester. Generally, students are allowed three

(3) excused absences in 15-week courses and one (1) excused absence in other course

timeframes (this includes absences due to illness or medical issue). Students who enroll in

specially designed weekend/summer courses may have other attendance requirements,

and should confirm attendance policies with the instructor prior to the start of the

class. Students must contact professors to discuss unavoidable absences extending

beyond these parameters and will subsequently be referred to Student Services for

discussion of next steps. Note: If a student plans to miss the first course meeting of a

semester, they should contact the professor well in advance, to avoid being dropped from

the course roster.

Summer Session

Summer courses are part of the OYR, Accelerated, Advanced Standing, and Dual

Degree

Programs. Required courses and electives are available during the summer

months of June,

July, and August for students to meet program requirements. Advanced Standing students

take courses in the summer before and/or after their

year of full-time study. Seats in the

summer sessions are available for Two-Year Program students if space permits.

Summer courses run for either five or 11 weeks. Courses in the 5-week session meet two

evenings per week; those in the 11-week session meet one evening per week. Students who

are required to take courses in the 11-week session, however, must be available two

evenings per week so they may take two courses during the Summer. Accelerated Program

students are required to take summer courses in the 11-week session, some of which will be

offered during the day.

Fields of Practice Specialization

The Silberman School of Social Work requires Second-Year Full-Time, Time Frame II

One Year Residency, and Accelerated students to choose a specialization in a Field of

Practice (FOP). As a reflection of both our commitment to a social justice and human

rights framework and the nature of the service systems where we do our work, the school

has chosen the following four FOP specializations: Aging; Child Welfare – Children,

Youth and Families; Health and Mental Health (a sub-specialization in World of Work is

now available); Global Social Work and Practice with Immigrants and Refugees.

Students select a Field of Practice (FOP) specialization in the spring of their foundation

year (in conjunction with planning their second-year field placement). OYR students

select their FOP with their Time Frame I advisor when confirming their agency plan. The

FOP specialization is organized around a population group of interest, agency or

institutional practice setting, or policy issue. The purpose of the field of practice

specialization is to accomplish the following:

24

1. Provide students with opportunities to develop in-depth knowledge and skill in an

area of social work beyond the method.

2. Better prepare students for a competitive job market given the current organization of

most service delivery systems.

3. Provide a potential cluster of faculty, students, and field agencies with similar interests

for developing and sharing knowledge about contemporary issues and trends.

4. Provide an additional vehicle for generating general innovation and new course

material in the curriculum.

5. Maintain the focus of the School, the faculty, and the curriculum on the changing

needs of a multicultural urban community.

Requirements for the completion of a Field of Practice specialization are: Work related

to the field of practice within the second-year field placement; and a corresponding FOP

platform course. Students will be informed of multiple opportunities for learning more

about the FOPs. They may also contact the following faculty members for additional

information:

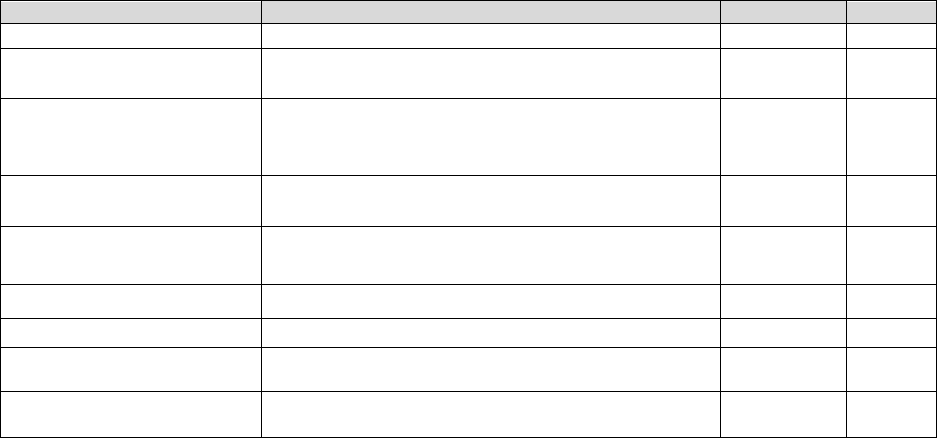

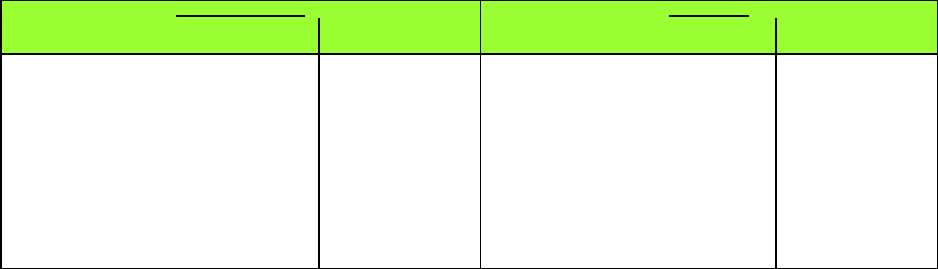

Chairs

Fields of Practice Specializations

Phone (212)

Room

Dr. Carmen Morano

Aging (Gerontology)

396-7547

448

Dr. Marina Lalayants

Child Welfare: Children, Youth

and Families

396-7550

451

Dr. Paul Kurzman

World of Work

(sub-specialization)

396-7537

434

Dr. Alexis Kuerbis

Health and Mental Health

396-7538

435

Dr. Martha Bragin

Global Social Work & Practice With

Immigrants & Refugees

396-7530

427

25

3THE ONE-YEAR RESIDENCY PROGRAM (OYR)

The OYR Program: Overview

Established in 1971 as the very first program of its kind, Silberman’s One-Year Residency

(OYR) Program is a unique work-study MSW pathway for social service professionals,

distinguished by a formal arrangement between the School and the student’s employer.

An adjusted work schedule and part-time class schedule allow OYR students to balance

professional and academic responsibilities over a roughly 27-month program period; this

includes the completion of a yearlong field practicum “residency” within the organization

where they already work, in a new, method-focused capacity.

Individuals are eligible for the OYR Program if they have completed a minimum of two

years of post-baccalaureate full-time employment in a social work-related role

within a recognized human service organization, and if their current employer agrees

to provide them with a field internship, approved by the school, during their second year

in the program. Students in the OYR Program are permitted to take up to 30 hours of

course work on a part-time basis while remaining in full-time employment. The OYR

Program is usually completed in two and a half years of continuous study, but in some

instances may take longer.

The One Year Residency Program is organized around three “time frames” made up of

both part-time and full-time study

.

Time Frame I: Part-time Evening Courses

The first phase or Time Frame I (TF I) of the OYR Program comprises evening

coursework. While remaining in full-time paid positions, OYR students take courses

two

evenings a week between 6:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. throughout

one complete academic

year (September to May) and the subsequent summer session. Students may take courses

offered during the day i

f their

work schedules permit. Three courses are taken in the first

semester of TF I, and three courses are taken in the second semester. (See model course

programs in Appendix A). Students earn 24 credits in this initial phase of the program. 24

earned credits are required, except in rare circumstances, for entrance into the residency

year phase of the program.

Time Frame II: Residency Year

The crux of the OYR Program is the student’s second-year field practicum – the

“residency” – within the organization where they already work. The time period during

which the student completes this field practicum residency is called Time Frame II. Prior

(and requisite) to their admission, the student’s employer agrees to provide them with a

yearlong internship, approved by the School, in a method-focused capacity distinct from

their existing role. The terms of this agreement are initiated in the agency executive

agreement; refined during Time Frame I in dialogue between the student, the Department

of Field Education, and the agency; and finalized in a written agreement/OYR contract

prior to the start of the residency. The details of Time Frame II are as follows:

26

The residency year includes four days of supervised field practicum per week and one day

of classes per week, over two semesters from September through May. In their single

yearlong practicum, OYR students must complete a minimum of 900 practicum hours.

The single practicum requirement is predicated on the student’s prior knowledge of social

service organizations and delivery of social services.

Agencies that enter an agreement with the School to support their employee as an OYR

student must commit to the provide the following throughout the in-house field

practicum:

1. Supervision of the student by a field instructor, who must meet all criteria

outlined in Chapter 4 below.

2. The designated field instructor cannot be the student’s current or previous

supervisor.

3. The assignment must be changed substantially from the student’s existing role,

to give the student a new learning experience.

4. The workload must be reduced for the same reason.

5. The assignment must be designed to provide learning experiences in the

student’s chosen Practice Method.

6. The student must have one day off per week from the agency to attend

c

la

sses.

Note: In the very unusual circumstance that a field agency is, or becomes, unable to

identify field instructors who holds a social work degree from a CSWE-accredited

institution, the School will collaborate with the agency to identify an alternative individual

to provide on-site task supervision for the student. Because the School believes that

formal social work supervision is vital to the student’s professional development, the

School and the agency will together ensure the provision of ongoing social work

supervision. If the School and agency are unable to solidify an arrangement for formal

social work supervision, students will not be placed within that field setting.

The student, the School, and the agency share responsibility for planning the OYR field

practicum, in accordance with these parameters, during TF I. The Field Education

Department will help the student plan their residency placement during the spring and

summer semesters of TF I, beginning with a preliminary planning form. The student is

responsible for returning the completed form to the Department of Field Education,

which will work with the agency to plan the placement.

All arrangements between the Department of Field Education and the agency should be

finalized by May 15 of TF I for residency in the following fall semester. The student may

not proceed into their residency year until the final written agreement has been submitted

and approved by the Field Education Department. A copy of this agreement will be sent

to the student when plans have been confirmed. The School reserves the right to

ultimately determine any student’s readiness for entry into Time Frame II.

27

If for any reason the employing agency cannot meet its educational commitment, or if

problems arise during residency planning, the student should immediately contact the

Field Education Department.

Students must be in good standing with their employer in order to enter TF II. They must

be actively able to undertake both their academic work and their field placement

responsibilities. If any disciplinary actions have been taken against the student by their

employer, or if the student takes a leave of absence from the agency for any reason, the

student needs to inform the Field Education Department right away.

If a student’s existing job changes during TF I, even if the change takes place within the

same agency, it is imperative that the student notify the Department of Field Education

immediately; a new agency executive agreement must be submitted before field practicum

planning can begin. If the student becomes employed at a new agency, the new agency

must agree to sponsor the student, and the School will work with the agency to provide a

proper field practicum assignment for the residency year. Any new job, at any agency,

must be approved as a residency placement by the Department of Field Education; and

the Department may delay residency placement until it determines that the student has

acclimated fully enough to begin a meaningful field placement. If the student becomes

employed at a new agency that does not agree to sponsor the student, or if the student