6

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

2020

© United Nations, June 2020. All rights reserved worldwide.

ISBN: 978-92-1-148345-1

eISBN: 978-92-1-005047-0

United Nations publication, Sales No. E.20.XI.6

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form

for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from

the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate

receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source.

Suggested citation:

World Drug Report 2020 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.20.XI.6).

No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose

whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNODC.

Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction,

should be addressed to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or

policies of UNODC or contributory organizations, nor does it imply any endorsement.

Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to:

Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

PO Box 500

1400 Vienna

Austria

Tel: (+43) 1 26060 0

Fax: (+43) 1 26060 5827

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.unodc.org/wdr2020

1

PREFACE

This is a time for science and solidarity, as United

Nations Secretary-General António Guterres has said,

highlighting the importance of trust in science and

of working together to respond to the global COVID-

19 pandemic.

The same holds true for our responses to the world

drug problem. To be effective, balanced solutions to

drug demand and supply must be rooted in evidence

and shared responsibility. This is more important

than ever, as illicit drug challenges become increas-

ingly complex, and the COVID-19 crisis and

economic downturn threaten to worsen their impacts,

on the poor, marginalized and vulnerable most of all.

Some 35.6 million people suffer from drug use dis-

orders globally. While more people use drugs in

developed countries than in developing countries,

and wealthier segments of society have a higher preva-

lence of drug use, people who are socially and

economically disadvantaged are more likely to develop

drug use disorders.

Only one out of eight people who need drug-related

treatment receive it. While one out of three drug users

is a woman, only one out of five people in treatment

is a woman. People in prison settings, minorities,

immigrants and displaced people also face barriers to

treatment due to discrimination and stigma. Of the

11 million people who inject drugs, half of them are

living with hepatitis C, and 1.4 million with HIV.

Around 269 million people used drugs in 2018, up

30 per cent from 2009, with adolescents and young

adults accounting for the largest share of users. More

people are using drugs, and there are more drugs, and

more types of drugs, than ever.

Seizures of amphetamines quadrupled between 2009

and 2018. Even as precursor control improves glob-

ally, traffickers and manufacturers are using designer

chemicals, devised to circumvent international con-

trols, to synthesize amphetamine, methamphetamine

and ecstasy. Production of heroin and cocaine remain

among the highest levels recorded in modern times.

The growth in global drug supply and demand poses

challenges to law enforcement, compounds health

risks and complicates efforts to prevent and treat drug

use disorders.

At the same time, more than 80% of the world’s

population, mostly living in low- and middle-income

countries, are deprived of access to controlled drugs

for pain relief and other essential medical uses.

Governments have repeatedly pledged to work

together to address the many challenges posed by the

world drug problem, as part of commitments to

achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and most

recently in the 2019 Ministerial Declaration adopted

by the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND). But

data indicates that development assistance to address

drug control has actually fallen over time.

Balanced, comprehensive and effective responses to

drugs depend on governments to live up to their

promises, and provide support to leave no one behind.

Health-centred, rights-based and gender-responsive

approaches to drug use and related diseases deliver

better public health outcomes. We need to do more

to share this learning and support implementation,

most of all in developing countries, including by

strengthening cooperation with civil society and

youth organizations.

The international community has an agreed legal

framework and the commitments outlined in the

2019 CND Ministerial Declaration. The United

Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) pro-

vides integrated support to build national capacities

and strengthen international cooperation to turn

pledges into effective action on the ground.

The theme for this year’s International Day against

Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, “Better Knowledge

for Better Care”, highlights the importance of scien-

tific evidence to strengthen responses to the world

drug problem and support the people who need us.

It also speaks to the ultimate goal of drug control,

namely the health and welfare of humankind.

Through learning and understanding we find com-

passion and seek solutions in solidarity.

It is in this spirit that I present the UNODC World

Drug Report 2020, and I urge governments and all

stakeholders to make the best use of this resource.

Ghada Waly

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

Acknowledgements

The World Drug Report 2020 was prepared by the Research and Trend Analysis Branch, Division for

Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), under the

supervision of Jean-Luc Lemahieu, Director of the Division, and Angela Me, Chief of the Research and

Trend Analysis Branch, and the coordination of Chloé Carpentier, Chief of the Drug Research Section.

Content overview

Chloé Carpentier

Angela Me

Analysis and drafting

Andrada-Maria Filip

Jaqueline Garcia-Yi

Barbara Hastie (Indiana University)

Kamran Niaz

Thomas Pietschmann

Editing

Jonathan Gibbons

Graphic design and production

Anja Korenblik

Suzanne Kunnen

Kristina Kuttnig

Federica Martinelli

Administrative support

Iulia Lazar

Review and comments

The World Drug Report 2020 benefited from the expertise of and invaluable contributions from

UNODC colleagues in all divisions.

The Research and Trend Analysis Branch acknowledges the invaluable contributions and advice

provided by the World Drug Report Scientific Advisory Committee:

Jonathan Caulkins

Paul Griffiths

Marya Hynes

Vicknasingam B. Kasinather

Charles Parry

Afarin Rahimi-Movaghar

Peter Reuter

Alison Ritter

Francisco Thoumi

The analysis on access to controlled medicines in Booklet 6 is based on original data graciously shared

by INCB and benefitted from the contribution of the Walther Center in Global Palliative Care of the

University of Indiana.

3

CONTENTS

BOOKLET 1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, IMPACT OF COVID-19, POLICY IMPLICATIONS

BOOKLET 2

DRUG USE AND HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

BOOKLET 3

DRUG SUPPLY

BOOKLET 4

CROSS-CUTTING ISSUES: EVOLVING TRENDS AND NEW CHALLENGES

BOOKLET 5

SOCIOECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS AND DRUG USE DISORDERS

BOOKLET 6

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

PREFACE ..................................................................................................................... 1

EXPLANATORY NOTES .............................................................................................. 5

SCOPE OF THE BOOKLET........................................................................................... 7

ACCESS TO CONTROLLED MEDICINES FOR PAIN MANAGEMENT .......................... 9

Global amounts of pharmaceutical opioids available for consumption ...................................... 9

Barriers to access to and availability of controlled medicines for pain management

and palliative care .......................................................................................................................... 16

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION ............................................................................ 22

Extent of implementation of international cooperation is mainly quantified

in terms of specific supply-side measures taken by law enforcement ....................................... 22

Development assistance dedicated to drug control has declined .............................................. 30

Has international cooperation led to global quantities of drugs seized growing

faster than global drug production? ............................................................................................ 35

ALTERNATIVE DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................ 37

Factors influencing resilience to illicit crop cultivation ............................................................... 38

Overview of alternative development projects in the period 2013–2017 ................................. 40

DRUGS AND VIOLENCE ........................................................................................... 48

The tripartite framework on drugs and violence ........................................................................ 48

Economic compulsive and psychopharmacological links between

psychoactive substances, violence and criminal activity .............................................................. 49

The systemic link: violence in the context of drug trafficking ................................................... 53

DRUGS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM ....................................................... 56

Cannabis is the drug that brings most people into contact with the

criminal justice system at the global level ................................................................................... 56

Women who are incarcerated for drug-related offences suffer long-lasting consequences ... 57

GLOSSARY ................................................................................................................ 59

REGIONAL GROUPINGS ........................................................................................... 61

5

EXPLANATORY NOTES

The designations employed and the presentation of

the material in the World Drug Report do not imply

the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the

part of the Secretariat of the United Nations con-

cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city

or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delim-

itation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Countries and areas are referred to by the names

that were in official use at the time the relevant data

were collected.

Since there is some scientific and legal ambiguity

about the distinctions between “drug use”, “drug

misuse” and “drug abuse”, the neutral term “drug

use” is used in the World Drug Report. The term

“misuse” is used only to denote the non-medical use

of prescription drugs.

All uses of the word “drug” and the term “drug use”

in the World Drug Report refer to substances con-

trolled under the international drug control

conventions, and their non-medical use.

All analysis contained in the World Drug Report is

based on the official data submitted by Member

States to the UNODC through the annual report

questionnaire unless indicated otherwise.

The data on population used in the World Drug

Report are taken from: World Population Prospects:

The 2019 Revision (United Nations, Department of

Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division).

References to dollars ($) are to United States dollars,

unless otherwise stated.

References to tons are to metric tons, unless other-

wise stated.

The following abbreviations have been used in the

present booklet:

AIDS acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome

ATS amphetamine-type stimulants

EMCDDA European Monitoring Centre for

Drugs and Drug Addiction

FARC Revolutionary Armed Forces of

Colombia

ha hectares

HIV human immunodeficiency virus

INCB International Narcotics Control

Board

INTERPOL International Criminal Police

Organization

OECD Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development

REDD+ UN Programme on Reducing

Emissions from Deforestation and

Forest Degradation

S-DDD defined daily doses for statistical

purposes

UNDP United Nations Development

Programme

UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs

and Crime

UNESCO United Nations Educational,

Scientific and Cultural Organization

WHO World Health Organization

7

SCOPE OF THE BOOKLET

This, the sixth booklet of the World Drug Report

2020, addresses a number of drug policy issues that

all form part of the international debate on the drug

problem and how to address it. Although compre-

hensive data and analysis may not be available for

some of these issues, the following chapters represent

a first attempt to consolidate available evidence

aimed at supporting the international community

in implementing several operational recommenda-

tions, including those contained in the outcome

document of the special session of the General

Assembly, held in 2016.

The booklet starts by considering the issue of ensur-

ing the availability of and access to controlled

substances exclusively for medical and scientific pur-

poses while preventing their diversion. It thus

reviews the latest data on and trends in the availabil-

ity of controlled medicines, specifically opioids, for

medical consumption at the global level and across

regions. An overview is also provided of the latest

survey findings on barriers to access to controlled

medicines for medical purposes in Member States.

Continuing with the strengthening of international

cooperation based on the principle of common and

shared responsibility, the booklet presents selected

data on international cooperation. The focus of this

chapter is rather limited considering the potentially

wide scope of the topic. It starts with an analysis of

trends with respect to a selected number of inter-

ventions in the area of drug supply reduction, on

which Member States are explicitly asked to report

annually to UNODC through the annual report

questionnaire. The chapter subsequently reviews the

financial means made available by donor countries

for international cooperation on drug issues, before

concluding with an analysis of interceptions trends,

a possible indicator of the success of international

cooperation.

The booklet then provides evidence to support the

implementation of operational recommendations

on alternative development and other development

and socioeconomic issues. This chapter presents the

findings of ongoing research aimed at assessing the

impact of alternative development projects in a

number of countries across different regions affected

by the illicit cultivation of opium poppy or coca

bush. It also provides an overview of the socioeco-

nomic drivers of illicit crop cultivation while

highlighting the specific vulnerabilities of the

affected communities and providing a first-ever esti-

mate of their potential size.

The booklet continues with a discussion of the nexus

between drugs and violence, starting from a con-

ceptual standpoint, and presenting research findings

that illustrate the different mechanisms at play. The

booklet then concludes with a short focus on drugs

and the criminal justice system, including estimates

of people arrested, convicted and held in prison for

drug offences, and a brief overview of the long-

lasting consequences of imprisonment for women

incarcerated for drug law offences.

9

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

period 1998–2010 was of oxycodone (which

experienced a tenfold growth over that period),

hydromorphone (fivefold growth), hydrocodone

(threefold growth) and oxymorphone (46,000-fold

growth). Methadone and buprenorphine, the

opioids used in medically assisted treatment of

opioid use disorders, also saw marked increases in

the amounts available for medical consumption at

the global level. The amount of fentanyl available

for medical consumption rose ninefold over the

period 1998–2010.

5

Moreover, since 2000, only

about 10 per cent of globally available morphine

was reported to have been used for palliative care,

5 Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated World Requirements for 2020

– Statistics for 2018 (E/INCB/2019/2), and previous years.

ACCESS TO CONTROLLED

MEDICINES FOR PAIN

MANAGEMENT

For nearly six decades, high-level declarations have

been made that affirm the international community’s

collective goal of a balanced, integrated, compre-

hensive, multidisciplinary and scientific

evidence-based approach to controlled medicines,

especially with respect to access and availability for

medical and scientific purposes. Despite recent

growing global advocacy, high-level statements of

intent and movements within international bodies

and individual countries to address access to and

availability of controlled medicines for pain man-

agement, progress has been extremely slow and

significant challenges and barriers remain in improv-

ing the accessibility and availability of controlled

medicines.

1, 2, 3, 4

Global amounts of pharma-

ceutical opioids available for

consumption

Access to and availability of controlled medicines

for pain relief, i.e., opioids, are unequally distributed

across the geographical regions and have had diverg-

ing trends in different regions. The amount of

opioids (expressed in daily doses) available for con-

sumption for medical purposes more than doubled

globally over the period 1998–2010, followed by a

period of stabilization and a decline over the period

2014–2018.

Most of the increase in the amount of pharmaceutical

opioids available for medical consumption over the

1 James F. Cleary and Martha A. Maurer, “Pain and policy

studies group: two decades of working to address regula-

tory barriers to improve opioid availability and accessibility

around the world”, Journal of Pain Symptoms Management,

vol. 55, No. 2 (February 2018), pp. S121–S134.

2 Lilian De Lima and Lukas Radbruch, “Palliative care in

the Global Health Agenda”, Journal of Pain and Palliative

Care Pharmacotherapy, vol. 28, No. 4 (October 2014), pp.

384–389.

3 Liiz Gwyther, Frank Brennan and Richard Harding,

“Advancing palliative care as a human right”, Journal of Pain

Symptom Management, vol. 38, No. 5 (September 2009),

pp. 767–774.

4 Human Rights Watch, “Please Do Not Make Us Suffer Any-

more…”: Access to Pain Treatment as a Human Right (March

2009).

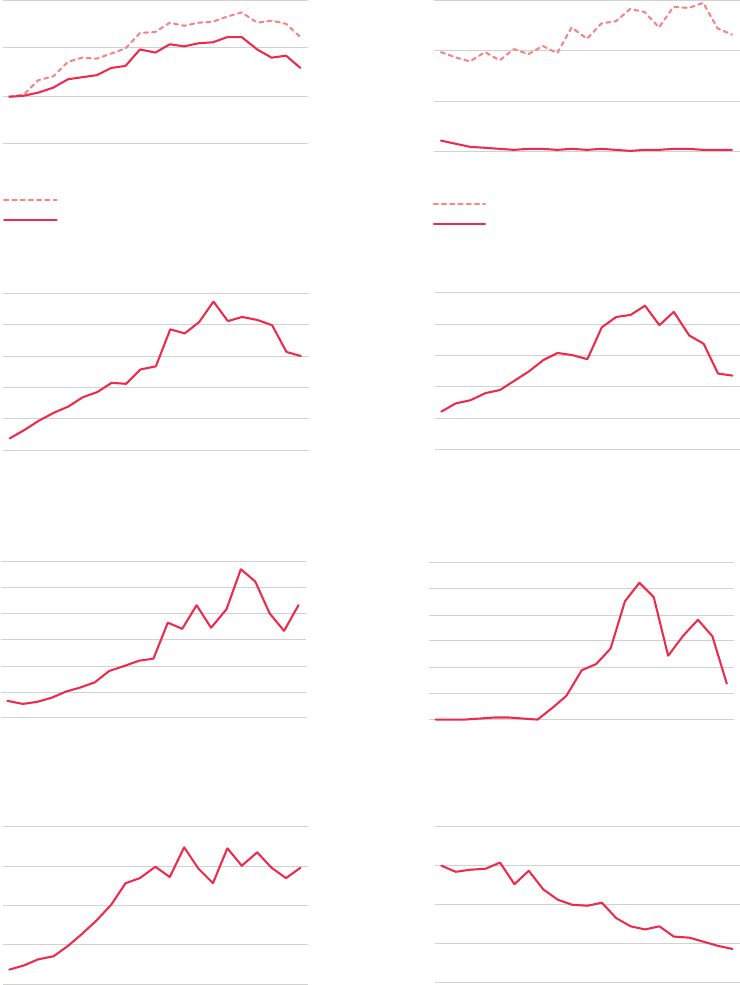

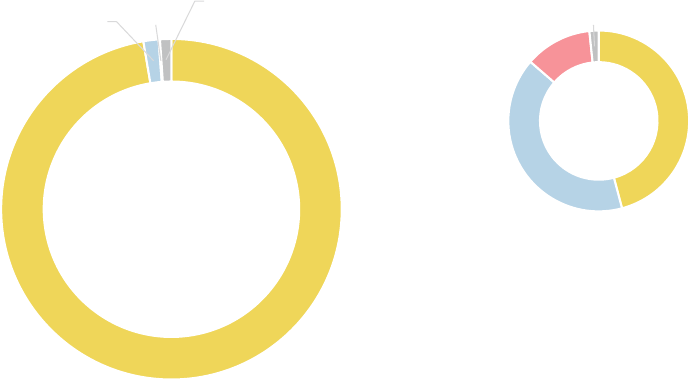

Fig. 1

Global amounts available for medical consump-

tion of pharmaceutical opioids under international

control, 1998–2018

Source: Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated World Requirements for 2020 –

Statistics for 2018 (E/INCB/2019/2).

Note: S-DDD refers to “defined daily doses for statistical purposes” as defined by

INCB. S-DDDs are “technical units of measurement” for the purposes of statistical

analysis and are not recommended daily prescription doses; actual doses may differ

based on treatments required and medical practices. The statistics exclude prepara-

tions of opioids listed in Schedule III of the 1961 Convention. Details of S-DDDs

used for these calculations are provided in the methodological annex of the present

report.

a

Substances used as analgesics, i.e., excluding substances used in opioid substitu-

tion treatment.

b

Substances used in opioid substitution treatment and as analgesics.

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Millions of S-DDD

Methadoneb

Synthetic opioids (analgesics)a

Buprenorphineb

Opiates (analgesics)a

All opiates

All opioids

Methadone

b

Synthec opioids (analgesics)

a

Buprenorphine

b

Opiates (analgesics)

a

All opiates

All opioids

10

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

Fig. 2

Global amounts available for medical consumption of selected opioids

(including preparations), 1998–2018

Source: Narcotic Drugs 2018: Estimated World Requirements for 2019 – Statistics for 2017 (E/INCB/2018/2), and previous years.

Note: All these substances are controlled under the 1961 Convention.

Morphine Codeine

Oxycodone Hydrocodone

Hydromorphone Oxymorphone

Fentanyl Pethidine

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Morphine, including preparations

Morphine

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

Codeine, including preparations

Codeine

Kilograms Kilograms Kilograms

Kilograms

Kilograms

Kilograms

Kilograms Kilograms

11

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

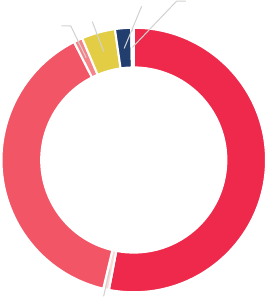

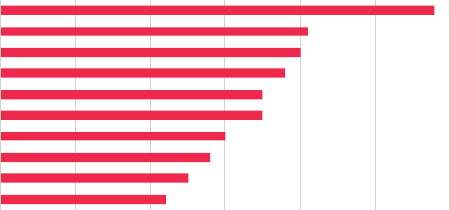

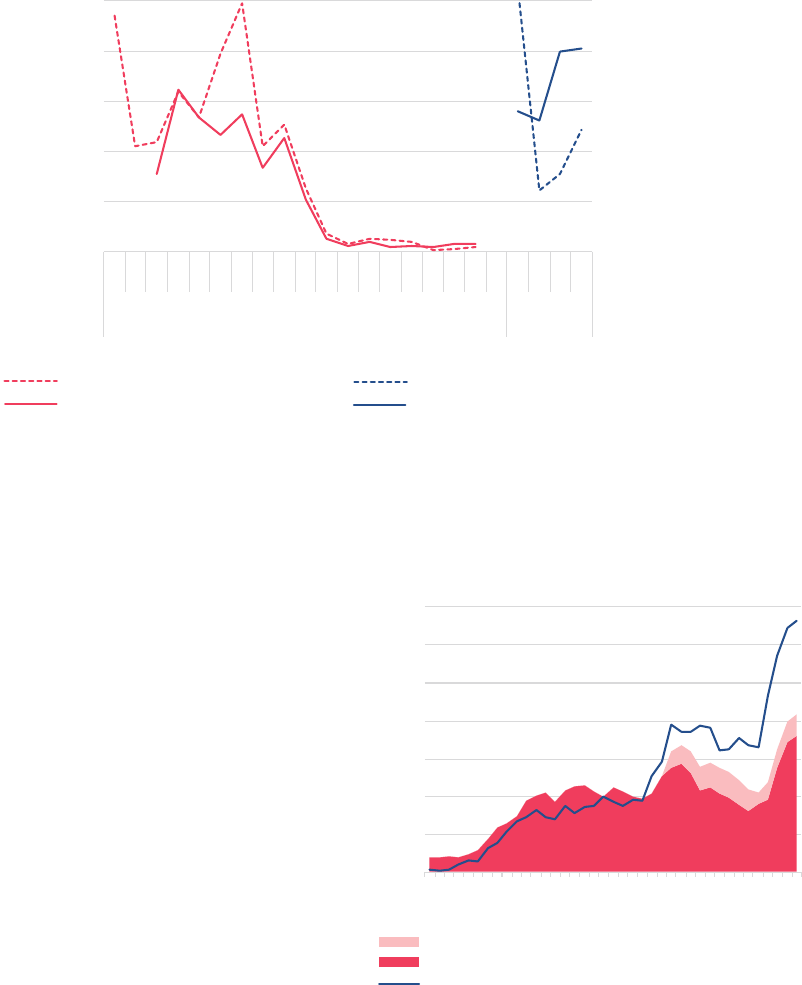

Fig. 3

Distribution of amounts available for medical

consumption of codeine, fentanyl, morphine,

pethidine and other opioids, expressed in stand-

ard defined daily doses (S-DDD), per subregion,

2018

Source: UNODC calculations based on Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated

World Requirements for 2020 – Statistics for 2018 (E/INCB/2019/2).

Note: S-DDD refers to “defined daily doses for statistical purposes” as defined

by INCB. S-DDDs are “technical units of measurement” for the purposes of sta-

tistical analysis and are not recommended daily prescription doses; actual doses

may differ based on treatments required and medical practices. Details of

S-DDDs used for these calculations are provided in the methodological annex

of the present report.

There is a gaping chasm between countries in the

availability of opioids for medical purposes. On the

basis of data on the amount of opioids available for

medical purposes, there is a clear disparity between

high-income countries versus low- and middle-

income countries

12

for all opioids combined (i.e.,

codeine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, morphine, oxy-

codone, pethidine and methadone).

Data for 2018 show that more than 90 per cent of

all pharmaceutical opioids that are available for med-

ical consumption are in high-income countries: 50

per cent in North America, around 40 per cent in

Europe, mostly in Western and Central Europe, and

a further 2 per cent in Oceania, mostly Australia

and New Zealand. Those high-income countries

11 See, for example, World Drug Report 2018 (United Nations

publication, Sales No. E.18.XI.9).

12 Based on the country classification 2014 of the World Bank

Country and Lending Groups.

while over 88 per cent was converted into codeine,

the majority of which (89 per cent) was used to

manufacture cough medicines.

6

Since 2014, the decline in the amount of opioids

available for medical consumption has been par-

ticularly pronounced for oxycodone, hydrocodone

and hydromorphone, following stricter rules aimed

at reducing diversion in North America. Prior to

that, these substances were heavily diverted to mar-

kets for non-medical use, particularly in North

America. Nonetheless, in 2018 that subregion con-

tinued to account for a major share of the global

amounts available for medical consumption of

hydromorphone (69 per cent), oxycodone (69 per

cent) and hydrocodone (99 per cent).

7

The amounts available for medical consumption of

some of the other synthetic opioids used in pain

management have been declining over the past two

decades. Pethidine is one example, with a 70 per

cent decline over the period 1998–2018, while

amounts available for medical consumption of dex-

tropropoxyphene, which was very popular in the

1990s, have decreased by more than 99 per cent

over the past two decades as the substance was

banned in a number of countries owing to concerns

over serious side effects.

8

The amount of fentanyl

available for medical consumption increased until

2010 but remained largely stable thereafter.

9

By contrast, the amounts of buprenorphine and

methadone available for medical consumption and

used in the medically assisted treatment of opioid

use disorders, have increased since 2014, especially

of buprenorphine, which rose by more than 50 per

cent over the period 2014–2018.

10

However, as with

other pharmaceutical opioids, there are large differ-

ences from one country to another in the

consumption patterns of buprenorphine and metha-

done for medical purposes, as seen in the coverage

of opioid-agonist treatment for people with opioid

use disorders.

11

6 Progress in Ensuring Adequate Access to Internationally

Controlled Substances for Medical and Scientific Purposes

(E/INCB/2018/Supp.1).

7 Ibid.

8 E/INCB/2019/2.

9 Narcotic Drugs 2018: Estimated World Requirements for 2019

– Statistics for 2017 (E/INCB/2018/2), and previous years.

10 Ibid.

North

America

53%

South America, Central

America, Caribbean

1%

Western

and

Central

Europe

39%

Eastern and

South-Eastern

Europe

1%

Asia

4%

Oceania

2%

Africa

0.3%

12

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

comprise around 12 per cent of the global popula-

tion. Therefore, low- and middle-income countries,

which are home to some 88 per cent of the global

population, are estimated to consume less than 10

per cent of the global amount of opioids available

for medical consumption.

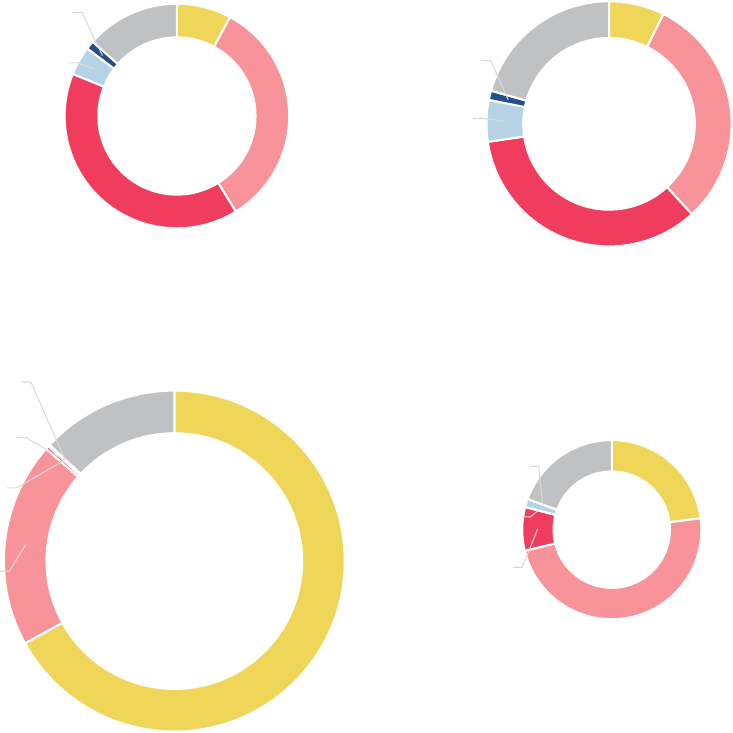

Even within each region or subregion, there is a

significant disparity in the consumption of opioids

for medical purposes. Over the period 2014–2018,

average consumption of opioids in countries in

North America ranged from some 100 defined daily

doses for statistical purposes (S-DDD) per million

inhabitants in Mexico to 32,700 S-DDD per mil-

lion inhabitants in the United States of America.

Similarly, in Western and Central Europe, estimates

ranged from close to 500 S-DDD per million inhab-

itants in Malta to 25,800 S-DDD per million

inhabitants in Germany. In Oceania, estimates

ranged from, on average, 15 S-DDD per million

inhabitants in Vanuatu to close to 11,600 S-DDD

per million inhabitants in Australia, and in Asia,

from 0.1 S-DDD per million inhabitants in Yemen

to close to 11,300 S-DDD per million inhabitants

in Israel.

Data show that there is a generally positive correla-

tion between gross national income and the

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

S-DDD per million inhabitants

North America

Western and

Central Europe

Oceania

East and South-eastern

Europe

South America, Central

America and the Caribbean

Asia

Africa

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

35,000

0 20,000 40,000 60,000 80,000 100,000

S-DDD per million inhabitants

Gross national income (GNI) per capita in current dollars

Fig. 5

Amounts available for medical consumption of

codeine, fentanyl, morphine, pethidine and other

opioids in individual countries, and per capita

income, average 2014–2018

Source: UNODC calculations based on Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated

World Requirements for 2020 – Statistics for 2018 (E/INCB/2019/2).

Note: S-DDD refers to “defined daily doses for statistical purposes” as defined

by INCB. S-DDDs are “technical units of measurement” for the purposes of sta-

tistical analysis and are not recommended daily prescription doses; actual doses

may differ based on treatments required and medical practices. Details of

S-DDDs used for these calculations are provided in the methodological annex of

the present report.

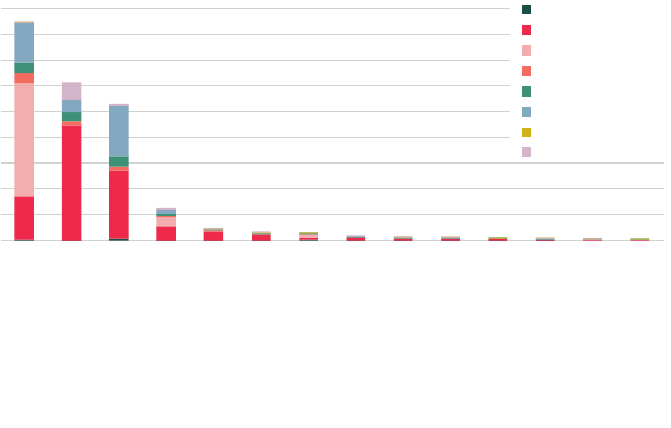

Fig. 4

Distribution of amounts available for medical consumption of codeine, fentanyl, morphine,

pethidine and other opioids, per country, 2018

Source: UNODC calculations based on Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated World Requirements for 2020 – Statistics for 2018

(E/INCB/2019/2).

Note: S-DDD refers to “defined daily doses for statistical purposes” as defined by INCB. S-DDDs are “technical units of measurement” for

the purposes of statistical analysis and are not recommended daily prescription doses; actual doses may differ based on treatments

required and medical practices. Details of S-DDDs used for these calculations are provided in the methodological annex of the present

report.

13

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

18,000

North America

Western and Central Europe

Australia and New Zealand

Global average

South-Eastern Europe

Near and Middle East/ South-West Asia

South America

Eastern Europe

Caribbean

East and South-East Asia

Central America

Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia

Africa

South-Asia

S-DDD per million inhabitants

Codeine

Fentanyl

Hydrocodone

Hydromorphone

Morphine

Oxycodone

Pethidine

Other

North America

Western and

Central Europe

Australia and

New Zealand

Global average

South-Eastern

Europe

Near and Middle East/

South-West Asia

South America

Eastern Europe

Caribbean

East and

South-East Asia

Central America

Melanesia, Polynesia

and Micronesia

Africa

South-Asia

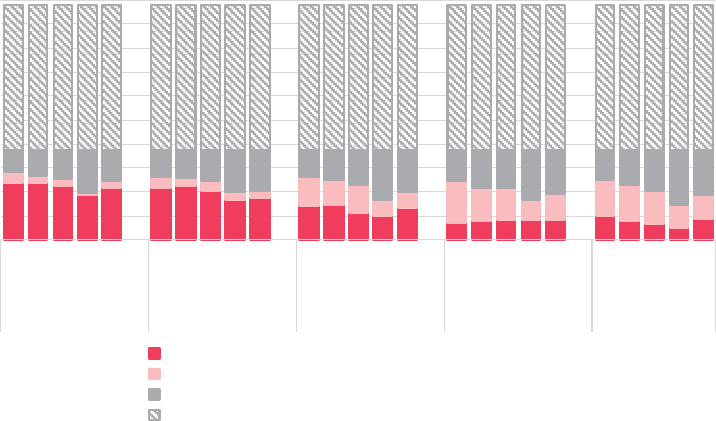

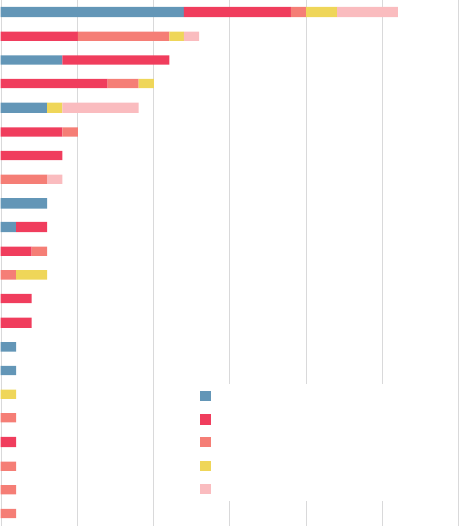

the availability of codeine for medical consumption

appears to be quite limited, although this may be a

statistical artefact as most codeine is sold in the form

of preparations, the sale of which – falling under

Schedule III of the 1961 Single Convention – is

internationally less strictly controlled and thus less

well documented than the sale of other pharmaceu-

tical opioids.

There have been concerted international and coun-

try-level efforts to address the inequity in the

consumption of pharmaceutical opioids,

13

particu

-

larly in the case of morphine, which has been on

the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for

management of pain due to cancer, HIV/AIDS and

other serious illnesses, and due to traumatic injuries,

burns and surgery, for nearly two decades.

14, 15

Despite this, morphine has not been accessible in

13 Cleary and Maurer, “Pain and policy studies group”.

14 De Lima and Radbruch, “Palliative care in the Global

Health Agenda”.

15 WHO, World Health Organization Model List of Essential

Medicines: 21th List (Geneva, 2019).

availability of pharmaceutical opioids for medical

purposes (R=0.67 over the period 2014–2018),

although a number of Asian countries and territories

with high gross national income per capita (such as

Macao, China, Hong Kong, China, Qatar, Singa-

pore, Japan and Kuwait) have very low levels of

opioid availability for medical purposes. This sug-

gests that the level of national income is not the

only factor that explains unequal availability across

countries. A number of barriers to access to opioids

for pain management are related to legislation, cul-

ture, health systems and prescribing practices.

Data also show discrepancies in the kind of phar

-

maceutical opioids available on the medical market.

While data for North America show that hydroco-

done is the most widely available pharmaceutical

opioid (in terms of daily doses per inhabitant), fen-

tanyl is the most widely available opioid in Western

and Central Europe and in Australia and New Zea-

land. The availability for medical consumption of

oxycodone is also relatively high in Australia and

New Zealand and in North America. By contrast,

Fig. 6

Amounts available for medical consumption of codeine, fentanyl, morphine, pethidine and

other opioids, by region and subregion,

a

2018

Source: UNODC calculations based on Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated World Requirements for 2020 – Statistics for 2018

(E/INCB/2019/2).

Note: S-DDD refers to “defined daily doses for statistical purposes” as defined by INCB. S-DDDs are “technical units of measurement” for

the purposes of statistical analysis and are not recommended daily prescription doses; actual doses may differ based on treatments

required and medical practices. Details of S-DDDs used for these calculations are provided in the methodological annex of the present

report

a

The regions and subregions are those designated by UNODC in the World Drug Report; they may partly differ from those used by INCB

in its publications.

14

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

the amounts of morphine available for medical con-

sumption in low- and middle-income countries has

increased slightly since 2014 (from 9.5 to 13 per

cent in 2018) the amount of morphine available per

person per country is still infinitesimally small to

non-existent in many developing countries, particu-

larly in South Asia and in Africa.

18, 19

Even though

countries may have morphine available for medical

use, many people still have limited access to it.

20, 21

WHO estimates that globally, each year 5.5 million

18 E/INCB/2018/Supp.1.

19 E/INCB/2019/2.

20 See section below on barriers to access to and availability of

controlled medicines for pain management and palliative

care.

21 E/INCB/2019/2.

adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms,

with assured quality and adequate information and

at a price that an individual and the community can

afford.

16, 17

In 2018, 87 per cent of the global amount of mor-

phine available for medical consumption was

estimated to have been consumed in high-income

countries, which are home to 12 per cent of the

global population. While the relative importance of

16 WHO, Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief into

Primary Health Care: A WHO Guide for Planners, Imple-

menters and Managers (Geneva, 2018).

17 Felicia Marie Knaul and others, “Alleviating the access abyss

in palliative care and pain relief: an imperative of universal

health coverage – the Lancet Commission report”, Lancet,

vol. 391, No. 10128 (April 2018).

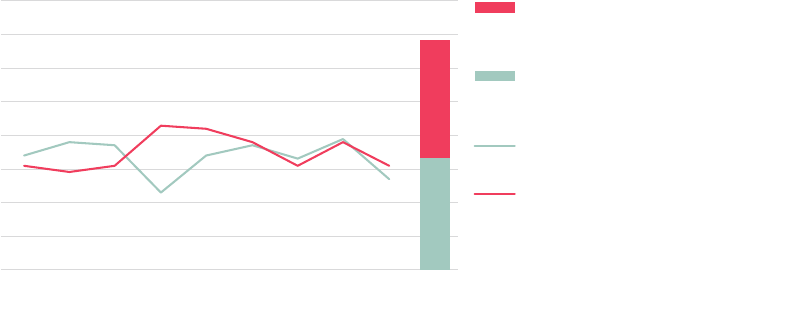

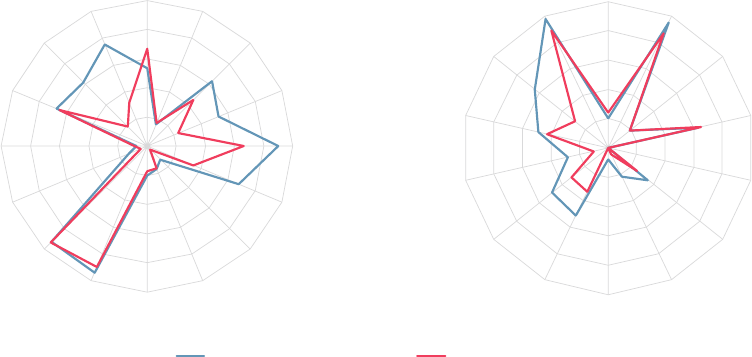

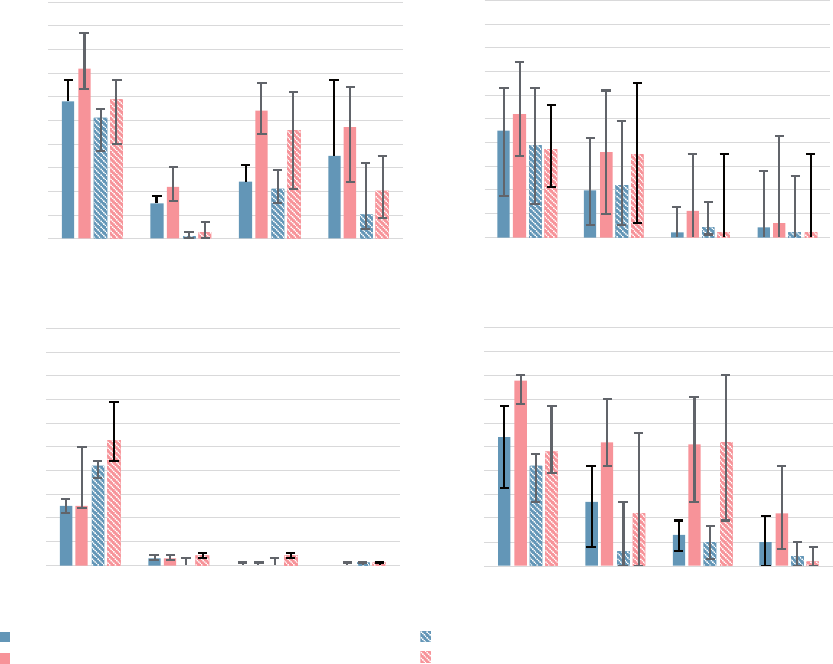

Fig. 7

Trends in availability of opioid analgesics for medical consumption, by region/subregion,

a

1998–2018

Source: UNODC calculations based on Narcotic Drugs 2019: Estimated World Requirements for 2020 – Statistics for 2018 (E/

INCB/2019/2) and previous years.

Note: S-DDD refers to “defined daily doses for statistical purposes” as defined by INCB. S-DDDs are “technical units of measurement” for

the purposes of statistical analysis and are not recommended daily prescription doses; actual doses may differ based on treatments

required and medical practices. Details of S-DDDs used for these calculations are provided in the methodological annex of the present

report.

a

Subregions and regions according to the classification used by UNODC in the World Drug Report; subregions and regions as defined

partly differ from those used by INCB in its publications; extrapolation techniques have been used in case of missing data.

b

Includes subregions above the global average, i.e., North America, Western and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand.

c

Includes regions and or subregions below the global average, i.e., Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, South-Eastern Europe, the Caribbean,

Central America and South America, as well as Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia, i.e., all regions and subregions except those of North

America, Western and Central Europe, and Australia and New Zealand.

High-consumption subregions

b

Low-consumption regions/subregions

c

0

200

400

600

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

S-DDD per million inhabitants

Eastern and South-Eastern Europe

South America, Central America and Caribbean

Near and Middle East/South-West Asia

East and South-East Asia

Oceania excluding Australia and New Zealand

Africa

South Asia

Central Asia and Transcaucasia

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

S-DDD per million inhabitants

North America

Western and Central Europe

Australia and New Zealand

Other countries

Global average

15

The role of complementary and alternative medicine in the

management of chronic non-cancer pain

The use of strong opioids, especially morphine, is gener-

ally considered the principal treatment for the manage-

ment of pain in palliative care for cancer patients.

a

The

treatment of chronic non-cancer pain, which is among

the most prevalent health conditions in many countries,

is often considered more difficult to manage, and its

treatment is sometimes more controversial.

b

Chronic

non-cancer pain is defined in scientific literature as pain

lasting for more than three months that stems from

injuries or illnesses other than cancer.

c

It is also consid-

ered that chronic pain results from a combination of

biological, psychological and social factors, and thus

requires a multifactorial approach to pain assessment,

patient monitoring and evaluation and long-term man-

agement. Some of the common conditions that cause

chronic pain include neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia

that may be caused by damage to the peripheral or cen-

tral nervous system, low back pain and osteoarthritis.

While opioids are used extensively in the management

of non-cancer chronic pain in some countries and set-

tings, in others, other drugs, as well as complementary

and alternative medicines, are used effectively in the

management of chronic pain whether related to cancer

or not.

d, e

Other than opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs are used in patients with osteoarthritis and rheu-

matoid arthritis and low back pain. The efficacy of anti-

depressant drugs has been reported for the management

of neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, low back pain and

headaches. Anti-convulsant drugs such as gabapentin,

pregabalin and carbamazepine have proved effective in

the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain.

f

As part of complementary and alternative medicine,

spinal manipulation is the most commonly used therapy

for low back pain.

g

Massage is another modality com-

monly used as a supplemental treatment for patients

with chronic non-cancer pain. Similarly, evidence sup-

ports the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment

of chronic low back pain, while results on the effective-

ness of acupuncture in the reduction of pain associated

with fibromyalgia and neck pain are promising.

h

Psychological interventions such as cognitive behav-

ioural therapy, relaxation training and hypnosis are the

most commonly used techniques in the management of

chronic pain.

i

The aim of such interventions is to help

the patient cope with the symptoms of pain, learn skills

for adaptation and self-management, and reduce disa-

bility associated with symptoms, rather than eliminate

physical causes of pain per se.

j

a

WHO, Ensuring Balance in National Policies on Controlled Sub-

stances: Guidance on Availability and Accessibility of Controlled

Medicines (Geneva, 2011).

b

Nora D. Volkow and A. Thomas McLellan, “Opioid abuse in

chronic pain: misconceptions and mitigation strategies”, New

England Journal of Medicine, vol. 374, No. 13 (March 2016), pp.

1253–1263.

c

Dennis C. Turk, Hilary D. Wilson and Alex Cahana, “Treatment

of chronic non-cancer pain”, Lancet, vol. 377, No. 9784 (June

2011), pp. 2226–2235.

d

Ibid.

e

Priyanka Singh and Aditi Chaturvedi, “Complementary and

alternative medicine in cancer pain management: a systematic

review”, Indian Journal of Palliative Care, vol. 21, No. 1 (2015),

pp. 105–115 (2015).

f

Turk, Wilson and Cahana, “Treatment of chronic non-cancer

pain”.

g

Ibid.

h

Ibid.

i

Singh and Chaturvedi, “Complementary and alternative medicine

in cancer pain management”.

j

Turk, Wilson and Cahana, “Treatment of chronic non-cancer

pain”.

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

available for medical consumption are reported in

North America, while overall increases are reported

in several other subregions, most notably South

America and the Near and Middle East/South-West

Asia, where availability has been low. This suggests

an overall increase in the availability of opioids in

developing countries, although that availability was

starting from, and remains at, a low level. Daily per

capita availability of pharmaceutical opioids more

terminal cancer patients and 1 million end-stage

HIV/AIDS patients do not have adequate treatment

for moderate to severe pain.

22

In recent years the huge disparity between countries

in the accessibility of opioids for medical purposes

has been reduced slightly: declines in opioids

22 WHO, Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief into

Primary Health Care.

16

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

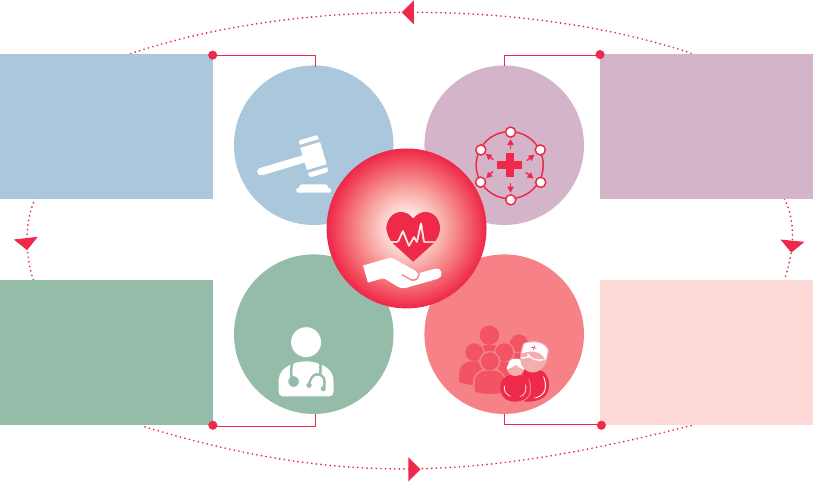

There are several challenges and barriers to access

to controlled medicines for pain management, all

of which are complex, multitiered and interrelated.

These include, but are not limited to, trade systems,

education, justice, foreign affairs, workforce and

development, but perhaps the most recognized and

salient among them are legislation and regulatory

systems, national supply management systems and

health systems. Each of these directly and indirectly

influences the barriers to both access to and avail-

ability of controlled medicines for pain management

and palliative care.

26

These challenges and barriers,

including the progress that has been made globally

to address them, are discussed below.

Legislation and regulatory systems

In 2018, INCB conducted a survey

27

of competent

national authorities in order to assess the barriers

and evaluate progress made at the national level in

improving access to and availability of controlled

substances for pain management since the previous

surveys in 1995, 2010 and 2014. Of the 130 coun-

tries (representing 78 per cent of the global

population) that responded, 40 per cent indicated

that over the previous five years, legislation and/or

regulatory systems had been reviewed or changed

to affect the availability of controlled medicines.

Some countries reported unspecified “general

changes,” others indicated that changes were made

to the status of controlled substances, while some

introduced electronic measures to facilitate prescrip

-

tions and/or procurement.

Although regulations that have limited the

availability of controlled medicine have been reduced

in many countries since 1995, challenges remain.

In 2018, 26 per cent of the countries that responded

to the survey mentioned the existence of legal

sanctions for unintentional errors in handling opioid

analgesics. The legal threat was reported to be a

major factor in the decisions of some doctors not

to procure, stock or prescribe opioids, thus limiting

their access. Similar challenges affect the number of

pharmacies that are willing to dispense opioids.

28

In 2018, the three major impediments to the

26 E/INCB/2018/Supp.1.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

than doubled in the regions and subregions where

availability was below the global average (i.e., Africa,

Asia, South America, Central America, the Carib-

bean, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, Melanesia,

Micronesia and Polynesia); taken together, availabil-

ity in these regions and subregions increased from

an average of 70 S-DDD per million inhabitants in

2010 to 180 S-DDD in 2018 (7 per cent of the

global per capita average).

23

By contrast, the availability of pharmaceutical opi-

oids for medical purposes declined by almost 50 per

cent in North America, from 32,550 S-DDD per

day per million inhabitants in 2010 to 16,910

S-DDD in 2018, thus approaching the levels

reported in Western and Central Europe (12,660

S-DDD) and in Australia and New Zealand (10,530

S-DDD) in 2018. Nevertheless, per capita availabil-

ity of pharmaceutical opioids for medical purposes

in North America remains comparatively high

(almost eight times the global average), in particular

when compared with the extremely low levels in

Africa and South Asia, as well as in Central Asia and

Transcaucasia, where there are no signs of

increases.

24

INCB notes that the increase in the use of expensive

synthetic opioids over the past two decades, which

has contributed to overconsumption and an “over-

dose epidemic” in some developed countries, has

not been matched by an increase in the use of afford-

able morphine, especially in low- and middle-income

countries.

25

Barriers to access to and

availability of controlled medi-

cines for pain management

and palliative care

The reasons for inequities in access to and availabil-

ity of opioids for pain management are extraordinarily

complex and include historical vestiges across mul-

tiple systems, i.e., government, health care and

society, as well as modern-day challenges, including

the concerns arising out of the opioid overdose crisis.

23 E/INCB/2019/2.

24 Ibid.

25 E/INCB/2018/Supp. 1.

17

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

health-care services and/or where the number of

physicians or doctors is limited.

In 2018, INCB also surveyed civil society organiza-

tions and received responses from 30 organizations

based in 23 countries in Asia, Africa, Europe and

the Americas.

31

More than half of the organizations

that responded to the questionnaire reported

changes to, or reviews of, legislation or regulations

aimed at simplifying and streamlining processes and

removing unduly restrictive regulations in order to

ensure accessibility of controlled substances and

maintain adequate control systems in their respec-

tive countries. Although this is a limited sample of

civil society organizations, it demonstrates a rela-

tively positive perception of some of the actions that

countries have taken to change or streamline the

laws and regulations that limit access to and avail-

ability of controlled medicines.

National supply management systems

Functional, effective and efficient national supply

chain management systems that are guided by the

international drug control conventions are critically

important to achieving the balance between prevent-

ing diversion and ensuring adequate access to and

31 Ibid.

availability of opioids, as reported by the countries

responding to the survey, were lack of training and

awareness of health-care professionals, fear of

addiction, and problems in sourcing opioid

medications.

29

Some evidence of progress in improving access to

and availability of controlled medicines for pain

management is suggested in a small proportion (16

per cent) of countries that reported that legislation

and regulations had been modified to broaden the

range of health-care professionals who are allowed

to prescribe controlled substances. Overall, 123

countries reported that they allow medical special-

ists to prescribe controlled substances for pain

management and palliative care, while 98 countries

also allow general practitioners. Challenges continue

to limit the range of health-care providers who can

prescribe opioid analgesics, as only nine countries

surveyed reported that their legislation allowed

nurses, including nurse practitioners, to prescribe

those drugs.

30

This legislative and regulatory limita-

tions on who can prescribe controlled substances

perpetuates a barrier to access, particularly in low-

and middle-income countries without decentralized

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

Patient,

family and

community

Health-care

systems and

providers

Supply

management

system

Legal

and

regulatory system

Opioid access

and palliative care

• Disparities in:

- Production/manufacturing

- Distribution channels

- Affordability

• Inadequate/inefficient in-country

monitoring/tracking systems

• Barriers tracking consumption

• Safeguards, storage, stock-outs

• Policies and programmes

• Capacity building and attitude

of health-care workers:

- Physicians

- Nurses and nurse practitioners

- Pharmacists

- Community health workers

- Spiritual care workers

• National policies

• International/national laws and

regulations

• Collaboration with international

organizations

- Competent authorities

work/train with INCB

- Training in-country enforcers

• Accessibility, availability,

affordability

• Patient, family and community

education

• Cultural biases and stigma

• Availability of community health

workers

• Safeguarding medicines

Systems and influences affecting access to and availability of controlled medicines

Systems and influences affecting access to and availability of controlled medicines

18

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

Fig. 9

Health-care providers allowed to prescribe controlled substances, 2018

Source: Progress in Ensuring Adequate Access to Internationally Controlled Substances for Medical and Scientific Purposes

(E/INCB/2018/Supp.1).

Note: The data represent the number of countries who responded to the survey and indicated the kind of health-care providers who can

prescribe controlled substances, including opioids for pain management and palliative care. Multiple responses were possible.

impediments to ensuring the availability of con-

trolled substances. To address this, INCB has

introduced a number of online and electronic sys-

tems to streamline and simplify import and export

processes within countries.

32

One improvement over

the years has been the gradual establishment of elec-

tronic tools for processing import and export

authorizations, with competent national authorities

in 50 countries reporting the use of such tools in

2018. In addition, with a view to facilitating the

production of reliable estimates of the quantities of

controlled substances needed nationally, guidelines

32 These include the National Drug Control System and the

International Import and Export Authorization System

(I2ES).

availability of controlled medicines for pain man-

agement and palliative care. Within national supply

chains and management systems, diverse domains

affect export, import, procurement and monitoring

of access to and availability of controlled medicines,

to name but a few. Within this chain, primary areas

that affect the accessibility of controlled substances

in a country are: (1) processes to produce national

estimates of controlled medicines for pain manage-

ment and palliative care; (2) assessment of the

availability of controlled substances; and (3) devel-

oping benchmarks (compared to thresholds for high

and low use of controlled substances).

Countries report that import and export control

measures or restrictions are among the main

Fig. 8

Reported impediments to the availability of controlled medicines for pain management, 2018

Source: Progress in Ensuring Adequate Access to Internationally Controlled Substances for Medical and Scientific Purposes

(E/INCB/2018/Supp.1).

Note: The percentage represents the proportion of responding countries that mentioned each of the factors as an impediment to the

availability of pain medications. Multiple responses were possible.

0

20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Others

Nurses (including nurse practitioners)

General practitioners (special licence)

Veterinarians

General practitioners

Medical specialists/psychiatrists, oncologists, surgeons, dentists)

Number of countries

Medical specialists/psychiatrists,

oncologists, surgeons, densts)

General praconers

Veterinarians

General praconers (special licence)

Nurses (including nurse praconers)

Others

0 10 20 30 40

Onerous regulations

Fear of prosecution/sanctions

Cultural attitudes

Limited financial resources

Trade control measures

Fear of diversion

Problems in sourcing

Fear of addiction

Lack of training/awareness of professionals

Percentage of countries

Lack of training/awareness of professionals

Fear of addicon

Problems in sourcing

Fear of diversion

Trade control measures

Limited nancial resources

Cultural atudes

Fear of prosecuon/sancons

Onerous regulaons

19

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

palliative care was included in the educational cur-

ricula in medical schools. Similarly, 76 countries

reported that continuing education, training and

information on palliative care, including on the

rational use and the importance of reducing the

misuse of prescription drugs, was provided to health-

care professionals. However, 11 countries reported

that education on palliative care was provided for

only a limited number of medical specialities, such

as oncology, and a further 43 countries reported

that palliative care was not included as a discipline

in their medical education programme. While nine

countries reported that they did not have a medical

school, four countries noted that they would build

palliative care into the medical curriculum from the

onset. This demonstrates an awareness, and a con-

certed effort, on the part of the medical profession

of the importance of palliative care training across

the life course of wider medical training.

In addition, 41 countries noted that national com-

petent authorities did not have training programmes

on the rational use of controlled substances and that

this was either due to a lack of resources or because

it was “not a priority” for the Government.

Regarding other fields of specialty with interaction

with patients and which are an important resource

in health-care delivery, especially in low- and middle-

income countries where the availability of doctors

is limited, the nursing profession has made significant

strides in incorporating palliative care and end-of-

life care training, not only in the curriculum for

for estimating the national requirements of con-

trolled substances have also been made available in

recent years.

33

Nevertheless, many countries, for a

myriad of reasons, continue to report to INCB that

they are unable to properly estimate or to monitor

consumption of controlled substances and continue

to inadequately or insufficiently estimate opioid

requirements.

Health systems

Improving the accessibility and availability of con-

trolled substances, including opioids for pain

management and palliative care, also requires

improving health systems to ensure controlled sub-

stances are prescribed and administered in a rational

and efficient manner.

34

Overall, the major steps

taken by countries that responded to the INCB

survey in 2018 included improvements to the health

insurance system and the setting of affordable prices

to improve the accessibility and availability of con-

trolled substances, including opioids for pain

management and palliative care.

Training and capacity-building

The training and capacity-building of health-care

professionals in all domains is key to ensuring access

to and availability of opioids for pain management.

In this regard, 71 countries (or 62 per cent of those

that responded to the INCB survey) reported that

33 INCB and WHO, Guide on Estimating Requirements for

Substances under International Control (Vienna, 2012).

34 E/INCB/2018/Supp. 1.

Fig. 10

Steps taken by countries to improve the accessibility of controlled substances, 2018

Source: Progress in Ensuring Adequate Access to Internationally Controlled Substances for Medical and Scientific Purposes

(E/INCB/2018/Supp.1).

Note: The data represent the number of countries that responded to the survey and indicated the steps taken to improve the accessibility

of controlled substances, including opioids for pain management and palliative care. Multiple responses were possible.

0 10 20 30 40 50

Monitoring and management

Procurement of essential drugs

Awareness-raising and training

Establishment of a list of essential medicines

Amendments to guidelines and legislation

No action

Improvement to the health insurance system and setting of affordable prices

Number of countries

Improvement to the health insurance system

and seng of aordable prices

No acon

Amendments to guidelines and legislaon

Establishment of a list of essenal medicines

Awareness-raising and training

Procurement of essenal drugs

Monitoring and management

20

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

reported by 130 countries.

42

Fear of addiction seems

to be related to a lack of awareness and training, and

to cultural attitudes.

43

These barriers influence all

systems and the people in them, including national

and international policymakers, regulators, health-

care professionals, community advocates, patients

and the public at large.

Moreover, at the global level, concerns over the non-

medical use of pharmaceutical opioids, triggered by

the opioid crisis in North America, North Africa,

and West and Central Africa has created a challenge

for increasing the availability of opioids for pain

management and palliative care due to the concomi-

tance of the two opposing needs. As a result,

low- and middle-income countries, not only in

Africa but also in other regions, some of which have

extremely limited access to opioids, are now facing

diminished access and have to counter increased

fear of addiction – that may result from a lack of

knowledge about substance use disorders and the

science of prevention and treatment – among poli-

cymakers, national authorities, health-care providers

and even among the public.

44, 45, 46, 47

Countries that reported to the 2018 INCB survey

mentioned specific initiatives undertaken by national

competent authorities to enhance the understanding

of, awareness of and education about, and address

cultural resistance to and the stigma associated with,

the use of opioids and other controlled substances:

education for representatives of the pharmaceutical

community, professionals and consumer groups; and

the promotion of ethical attitudes among medical

doctors and pharmaceutical companies, in particular

to reduce the excessive marketing of opioids.

48

42 E/INCB/2018/Supp.1.

43 Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs: Ensuring

Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes –

Indispensable, Adequately Available and not Unduly Restricted

(E/INCB/2015/1/Supp.1).

44 Knaul and others, “Alleviating the access abyss in palliative

care and pain relief”.

45 African Palliative Care Association, Guidelines for Ensuring

Patient Access to, and Safe Management of, Controlled Medi-

cines (Kampala, 2013).

46 De Lima and Radbruch, “Palliative care in the Global

Health Agenda”.

47 Pettus and others, “Ensuring and restoring balance on

access to controlled substances for medical and scientific

purposes”.

48 E/INCB/2018/Supp.1.

nurses but also for them to train other health-care

providers within the larger health-care community.

35,

36, 37

For example, many non-governmental

organizations in Africa have initiated programmes

for training community health-care workers in

palliative care, who do not necessarily require

licensure and do not undergo extensive formal

training in medicine, pharmacy or nursing.

38

In

resource-constrained settings, community health-

care workers are considered quite instrumental in

providing care outside urban areas, in villages and

other community settings with limited access to

formal health-care services and facilities.

39

Pharmacy training is gaining attention given the

frontline role of pharmacies in making opioids

accessible for patients. Palliative care training is not

mandatory but many programmes, including by

non-governmental organizations and other advocacy

organizations, are targeting pharmacy professionals.

40

Education and awareness-raising

Lack of awareness and “fear of addiction”, i.e., the

concern that patients who are prescribed strong opi-

oids are likely to develop dependence or iatrogenic

addiction,

41

were reported to be among the top

impediments to access to controlled substances

35 A leading programme is the End-of-Life Nursing Education

Consortium, which is based on a train-the-trainer model

and has been implemented in over 100 countries worldwide.

36 Betty Ferrel, Pam Malloy and Rose Virani, “The end of life

nursing education nursing consortium project”, Annals of

Palliative Medicine, vol. 4, No. 2 (April 2015), pp. 61–69.

37 Henry Ddungu, “Palliative care: what approaches are suit-

able in developing countries?”, British Journal of Haematol-

ogy”, vol. 154, No. 6 (September 2011), pp. 728–735.

38 The African Palliative Care Association is one leading

organization working in this area. See, for instance, Annual

Report: Building Bridges 2017-18 (Kampala, 2019).

39 Katherine Pettus and others, “Ensuring and restoring bal-

ance on access to controlled substances for medical and

scientific purposes: joint statement from palliative care

organizations”, Journal of Pain Palliative Care and Pharmaco-

therapy, vol. 32, No. 2–3 (September 2018), pp. 124–128.

40 African Palliative Care Association, Annual Report: Building

Bridges 2017-18.

41 A structured review of 67 studies found that 3 per cent

of chronic non-cancer patients regularly taking opioids

developed opioid use disorders. See David A. Fishbain and

others, “What percentage of chronic non-malignant pain

patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop

abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug related behaviours?

A structured evidence-based review”, Pain Medicine, vol. 9,

No. 4 (May 2008), pp. 444-459.

21

Access to controlled medicines for pain management

6

and in most low- and middle-income countries,

where a large number of people are not covered by

either health insurance or a national health-care

system, many people can encounter difficulties in

accessing the pain medications that they need.

50

International cooperation and

coordination

For many years, Governments, academic institutions

and non-governmental organizations have worked

across and within systems nationally and interna-

tionally on the central principle of balance between

access to controlled substances for medical and sci-

entific purposes and prevention of their diversion.

Over the past 20 years, demonstrable progress has

been made in over 30 countries in this regard.

51

Similarly, collaboration between international stake-

holders that aim to improve the legislative

framework, build capacity of health-care profession-

als, and work with patients, families and the public

in order to improve access to and availability of

controlled substances has shown the importance of

working across these major domains. Each of them

could act as an impediment or serve to enable access

to opioids for pain management and palliative care

at the country level.

50 Ibid.

51 Cleary and Maurer, “Pain and policy studies group”.

Affordability

The availability of pain medications is determined

by factors that include their physical availability and

practical accessibility. These in turn depend on the

extent to which pain medications are procured and

the existence of an appropriate and viable health

system. Furthermore, the affordability of those medi-

cations is central to all of the elements, especially in

the context of universal health coverage. Affordabil-

ity is addressed, among other ways, by ensuring

funding for the purchase of opioid medications as

well as developing and improving health insurance

and reimbursement schemes that guarantee access

to pain medication.

49

In 2018, 50 countries reported

to INCB that steps had been taken towards improv-

ing their health insurance systems and setting

affordable prices for essential medicines, including

opioids. However, limited resources can impair even

a well-intended Government from procurement or

preclude it from providing or subsidizing controlled

medicines for pain management. Other issues that

may affect the affordability of pain medications

include licensing, taxation, poor or inefficient dis-

tribution systems, lack of reimbursement and lack

of availability of inexpensive formulations. Even in

the case of Governments that are strongly commit-

ted to addressing challenges and barriers to access,

financial resources may not be available to make

systemic changes. Moreover, because of the high cost

of pain medications, in many high-income countries

49 Ibid.

Fig. 11

Education and awareness-raising initiatives, 2018

Source: Progress in Ensuring Adequate Access to Internationally Controlled Substances for Medical and Scientific Purposes

(E/INCB/2018/Supp.1).

Note: The data represent the number of countries that responded to the survey and indicated the initiatives taken by the competent

national authorities for education and awareness to improve the accessibility of controlled substances, including opioids for pain manage-

ment and palliative care. Multiple responses were possible.

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Reducing excessive marketing

Overcoming cultural resistance

Reduction of stigma and fear of addiction

Education for the general public

Palliative care education in curricula

Engagement of civil society and non-governmental organizations

Prevention of non-medical use of psychotropic substances

Promotion of ethical attitudes

Media campaigns

Education for pharmaceutical community

Number of countries

22

WORLD DRUG REPORT 2020

OTHER DRUG POLICY ISSUES

should be kept in mind, even though it is not dis-

cussed further in this chapter.

The purpose of this chapter is to present and exam-

ine the information that countries have regularly

submitted to UNODC on the topic of international

cooperation. Its scope is relatively limited and it does

not pretend to cover the complex nature of factors

that influence the implementation of international

cooperation measures and their outcomes.

Extent of implementation of

international cooperation is

mainly quantified in terms of

specific supply-side measures

taken by law enforcement

Reporting on the implementation of international

cooperation globally is challenging because interna-

tional cooperation can take different forms, which

are difficult to measure. For example, the sharing of

intelligence information, probably the most common

form of cooperation to address drug-related matters,

happens in day-to-day work within and across law

enforcement agencies; and it is hardly recorded in

any systematic way at the national level in most coun-

tries. Records exist of some forms of

intelligence-sharing at the international level, but

information on such sharing is not necessarily

reported by individual countries.

On an annual basis, countries report to UNODC

on key activities related to international cooperation

in the field of drug supply, including on joint opera-

tions with other countries, controlled deliveries,

exchanges of liaison officers and the exchange of

information. The reporting includes information

on whether such activities took place during the

reference year. In most countries and at the inter-

national level, no information is collected to assess

the actual quality or the effectiveness of such coop-

eration activities.

While the proportion of countries that at least par-

tially complete the section on international

cooperation in their annual data submissions is quite

high (close to 100 per cent of all countries report-

ing information to UNODC), a significant number

of countries do not submit any information on inter-

national cooperation to UNODC; for example, out

INTERNATIONAL

COOPERATION

It is generally acknowledged that the drug problem

is not restricted to just one country, but that it affects

most countries in an intertwined manner. Responses

to the drug problem at the national level are neces-

sary, but they are not sufficient to cope with the

global drug problem unless they are also well coor-

dinated across countries. For example, interventions

in one country, leading to a reduction in the drug

supply, may prompt a replacement effect, with

supply increasingly originating in other countries.

Similarly, successful demand reduction efforts in

just one country may prompt organized crime

groups to devise strategies for targeting other coun-

tries and trigger increasing demand for drugs at the

regional or global level. In short, global drug markets

tend to be extremely resilient to attempts to solve

the drug problem exclusively at the national level.

One of the key approaches to addressing the trans-

national nature of the drug problem has been the

strengthening of international cooperation, both

with a view to improving coordination of policies

and interventions and assisting countries with lim-

ited resources and capacities in undertaking the

necessary interventions. International cooperation

can take many forms, including intergovernmental

cooperation frameworks and mechanisms, the devel-

opment of standards and guidelines that promote

best practices in the fields of drug demand reduc-

tion

52

or drug supply reduction, and capacity-building

initiatives that strengthen the ability of countries to

counter the drug problem.

A comprehensive analysis of international coopera-

tion on drug-related issues, which may be

implemented at different levels, whether geographi-

cally or thematically, involving a plurality of

mechanisms and actors – even if only done concep-

tually – would go far beyond the scope of this

edition of the World Drug Report. Nonetheless, this

broad range of international cooperation activities

52 See, for example, UNODC and WHO, International

Standards on Drug Use Prevention, second updated edition

(Vienna, 2018); UNESCO, UNODC and WHO, Good