ICE Faces Barriers in

Timely Repatriation

of Detained Aliens

March 11, 2019

OIG-19-28

DHS OIG HIGHLIGHTS

ICE Faces Barriers in Timely Repatriation

of Detained Aliens

March 11, 2019

Why We

Did This

Review

The Department of

Homeland Security U.S.

Immigration and Customs

Enforcement (ICE)

repatriates thousands of

aliens every year. In this

review, we sought to

identify barriers to the

repatriation of detained

aliens with final orders of

removal.

What We

Recommend

We made five

recommendations to

improve ICE’s removal

operations staffing, flight

reservation system, and

metrics related to visa

sanctions.

For Further Information:

Contact our Office of Public Affairs at

(202) 981-6000, or email us at

What We Found

Our case review of 3,053 aliens not removed within 90

days of receiving a final order of removal revealed that the

most significant factors delaying or preventing repatriation

are external and beyond ICE’s control. Specifically,

detainees’ legal appeals tend to be lengthy; removals are

dependent on foreign governments cooperating to arrange

travel documents and flight schedules; detainees may fail

to comply with repatriation efforts; and detainees’ physical

or mental health conditions can further delay removals.

Internally, ICE’s challenges with staffing and technology

also diminish the efficiency of the removal process. ICE

struggles with inadequate staffing, heavy caseloads, and

frequent officer rotations, causing the quality of case

management for detainees with final orders of removal to

suffer. In addition, ICE Air Operations manages complex

logistical movements for commercial and charter flights

through a cumbersome and inefficient manual process.

Finally, even though ICE has developed a tool to track and

report statistics for removal operations, the metrics are

incomplete and do not track information needed for fact-

based decisions on visa sanctions.

ICE Response

ICE officials concurred with all five recommendations and

proposed steps to address staffing, training, web-based

case management and tracking, and decision-making

processes.

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Washington, DC 20528 / www.oig.dhs.gov

0DUFK

MEMORANDUM FOR: Ronald D. Vitiello

Senior Official Performing the Duties of Director

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

FROM: John V. Kelly

Acting Inspector General

SUBJECT: ICE Faces Barriers in Timely Repatriation of Detained

Aliens

Attached for your action is our final report, ICE Faces Barriers in Timely

Repatriation of Detained Aliens. We incorporated the formal comments provided

by your office.

The report contains five recommendations aimed at improving ICE’s removal

operations. Your office concurred with all five recommendations. Based on

information provided in your response to the draft report, we consider all five

recommendations open and resolved. Once your office has fully implemented

the recommendations, please submit a formal closeout letter to us within 30

days so that we may close the recommendations. The memorandum should be

accompanied by evidence of completion of agreed-upon corrective actions.

Please send your response or closure request to

Consistent with our responsibility under the Inspector General Act, we will

provide copies of our report to congressional committees with oversight and

appropriation responsibility over the Department of Homeland Security. We will

post the report on our website for public dissemination.

Please call me with any questions, or your staff may contact Jennifer L.

Costello, Deputy Inspector General, at (202) 981-6000, or Tatyana Martell,

Chief Inspector, at (202) 981-6117.

Attachment

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Table of Contents

Background .................................................................................................... 2

Results of Review ............................................................................................ 3

External Barriers Delay or Obstruct the Removal Process ...................... 4

Internal Challenges with ICE Staffing, Technology, and Accuracy of ICE

Metrics Limit Efficiency of Removals .................................................... 14

Recommendations......................................................................................... 20

Appendixes

Appendix A: Objective, Scope, and Methodology ................................. 23

Appendix B: ICE Comments to the Draft Report ................................... 25

Appendix C: Results of Electronic File Case Review .............................. 28

Appendix D: Countries’ Cooperation with Repatriation ......................... 29

Appendix E: Travel Document Requests .............................................. 32

Appendix F: Office of Special Reviews and Evaluations Major

Contributors to This Report ................................................................. 33

Appendix G: Report Distribution .......................................................... 34

Abbreviations

ERO Enforcement and Removal Operations

eTD electronic Travel Document

GAO Government Accountability Office

ICE U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

OIG Office of Inspector General

RCI Tool Removal Cooperation Initiative Tool

U.S.C. United States Code

USCIS U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Background

Every year, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) repatriates

thousands of aliens with final orders of removal. In fiscal year 2017, ICE

removed 226,119 aliens who came from 189 countries.

1

ICE Enforcement and

Removal Operations (ERO) must generally remove detained aliens (detainees)

within 90 days of receiving a final order of removal from a Department of

Justice Federal immigration judge or, in limited circumstances, an authorized

Department of Homeland Security official, for violating immigration laws.

2

Two

exceptions stop the 90-day “clock”: if a detainee appeals the final order

3

or if a

detainee obstructs (fails to comply with) the removal process.

4

For aliens with

final removal orders who remain in custody longer than 6 months, ICE must

generally release them unless there is a significant likelihood that they will be

removed within a reasonable time in the future.

5

ICE typically repatriates detainees via commercial flights, charter flights,

6

or

Special High Risk Charters,

7

with the exception of Mexican nationals who are

repatriated across the land border. ICE ERO’s 24 field offices are responsible

for detainee case management (i.e., the “detained docket”) and for providing

flight escorts when needed. Within ICE, ICE Air Operations (ICE Air),

coordinates repatriation flights. Detainees on a direct flight to their country of

citizenship may leave unescorted on a commercial flight, while ICE deportation

officers may escort detainees scheduled for removal on commercial flights that

require transit through a third country, or detainees who present a security

risk. ICE uses charter flights when there are numerous detainees scheduled for

removal to the same geographic location, or there are medical or security

requirements that cannot be managed on a commercial flight.

1

In FY 2015, ICE removed 235,413 aliens and in FY 2016, ICE removed 240,255 aliens.

2

8 United States Code (U.S.C.) § 1231(a)(1)(A)

3

8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(1)(B)(ii)

4

8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(1)(C)

5

Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678, 701 (2001); see also Clark v. Martinez, 543 U.S. 371, 378

(2005) (extending Zadvydas to inadmissible aliens). See DHS Office of Inspector General’s (OIG)

prior report ICE’s Compliance With Detention Limits for Aliens With a Final Order of Removal

From the United States, OIG-07-28, for information on the limited exceptions to this release

requirement for public health and national security cases.

6

ICE contracts with a private company to supply flights and flight crew used solely to

repatriate aliens with final orders of removal. ICE determines which aliens will be placed on the

charter flights, and ICE staff accompanies the detainees to their destination.

7

Special High Risk Charters are charter flights to repatriate detainees who resist removal

efforts or to return a group of detainees when their government issues multiple travel

documents at once. ICE may add cooperative detainees to these flights if seats are available.

www.oig.dhs.gov 2 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Repatriation requires cooperation from other stakeholders as foreign

governments must issue passports or other authorized travel documents, agree

to transportation arrangements, and issue visas to ICE staff escorting aliens to

their destination. If foreign governments do not cooperate with ICE, DHS may

impose visa sanctions, which the State Department administers.

8

In 2017,

DHS and the State Department signed a Memorandum of Understanding in

which ICE was designated responsible for monitoring the ability and

willingness of countries to cooperate with repatriation.

9

Within ICE, ERO is

responsible for this oversight.

This report identifies barriers to repatriating detained aliens with final orders of

removal. DHS’ case management data systems have limited capability to track,

report on, and analyze immigration outcomes and decisions.

10

Because DHS

does not have reliable statistics on removal challenges, we took a snapshot of

all aliens with final orders of removal in ICE detention on December 13, 2017,

to better understand the delays and barriers. On that date, there were 13,217

detainees total, 3,053 (23 percent) of whom had not been removed within the

90-day timeframe. We focused our case review on these 3,053 cases and asked

ICE to provide us with a case disposition as of March 24, 2018. We then

assessed whether the delays and barriers we identified prolonged detention or

prevented removal. Unless otherwise identified, the numbers used in this

report are from our analysis and do not represent official ICE statistics.

Appendix A provides more information on our scope and methodology.

Results of Review

Our case review of 3,053 aliens not removed within the prescribed 90-day

timeframe revealed that the most significant factors delaying or preventing

repatriation are external and beyond ICE’s control. Specifically, detainees’ legal

appeals tend to be lengthy; removals are dependent on foreign governments

cooperating to arrange travel documents and flight schedules; detainees may

fail to comply with repatriation efforts; and detainee physical and mental

health conditions can further delay removals.

Internally, ICE’s challenges with staffing and technology also diminish the

efficiency of the removal process. ICE struggles with inadequate staffing, heavy

caseloads, and frequent officer rotations, causing the quality of case

8

8 U.S.C. § 1253(d). Visa sanctions deny visas to enter the United States for the citizens of

uncooperative countries. For example, the United States might stop issuing tourist visas or

visas to the families of diplomats.

9

Memorandum of Understanding Between the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the

U.S. Department of State Concerning the Removal of Aliens, August 16, 2017, Section VI

10

DHS OIG, DHS Needs a More Unified Approach to Immigration Enforcement and

Administration, OIG-18-07, October 30, 2017

www.oig.dhs.gov 3 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

management for detainees with final orders of removal to suffer. In addition,

ICE Air manages complex logistical movements for commercial and charter

flights through a cumbersome and inefficient manual process. Finally, even

though ICE has developed a tool to track and report statistics for removal

operations, the metrics are incomplete and do not provide information needed

for fact-based decisions on visa sanctions.

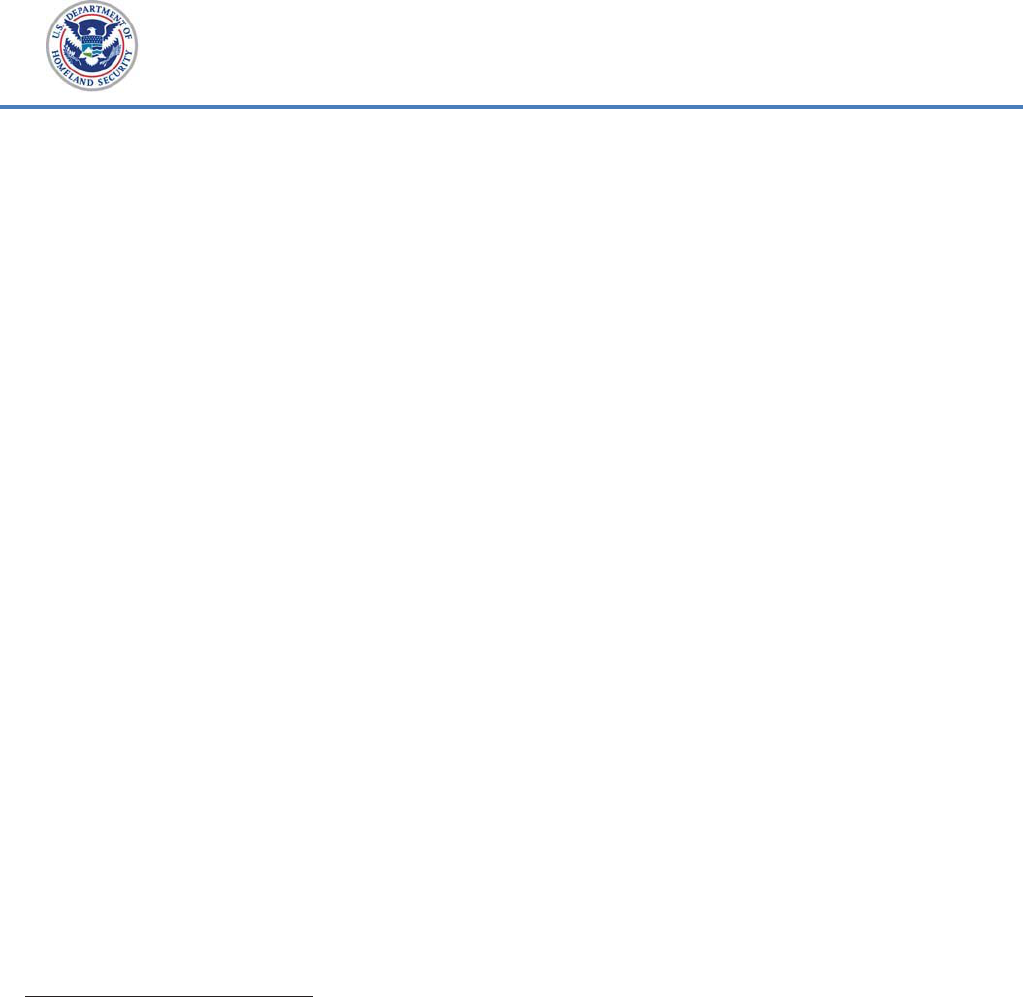

External Barriers Delay or Obstruct the Removal Process

Based on our case review, the two predominant factors delaying repatriation

are legal appeals and obtaining travel documents. Legal appeals are complex

and the backlog in immigration courts directly impacts the timeliness of the

appeals, while issuance of travel documents is hindered by some foreign

governments’ unwillingness or lack of capacity to cooperate with the

repatriation process. Foreign government cooperation is also necessary for

coordinating repatriation flights and escort visas. Additional obstructions

include instances when detainees fail to comply with removal proceedings or

when their medical conditions negatively impact repatriation. Figure 1

illustrates the percentage of removals delayed by each factor.

Figure 1: Delays and External Barriers to Removal

11

55%

31%

6%

3%

3% 1% 1%

Legal Challenges & Appeals (1,670)

Travel Document (948)

Flight Arrangements (201)

Failure To Comply (93)

Other (85)

Escorts (37)

Medical (19)

Source: OIG Analysis of Aliens Detained Longer than 90 Days Post Final Order of Removal,

from ICE ENFORCE Alien Removal Module

11

Most of the 85 cases in our file review marked “Other” were too complex and varied to

categorize. Examples include aliens who:

x alternated between failure to comply, legal appeals, requests to withdraw legal

appeals, and revised citizenship claims;

x were not in ICE’s physical custody because they were being prosecuted for, or were

witnesses in the prosecution of, crimes; or

x were granted a form of relief from removal to their country of citizenship, but were

still in ICE custody while ICE determined whether they could be removed to a third

country.

www.oig.dhs.gov 4 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Legal Appeals Delay Removals

An alien with a final order of removal may challenge the decision at any time

before removal is achieved. While legal challenges are pending, ICE generally

cannot repatriate an alien,

12

but may continue detention until the appeal or

other challenge is resolved. Legal appeals ensure aliens receive due process

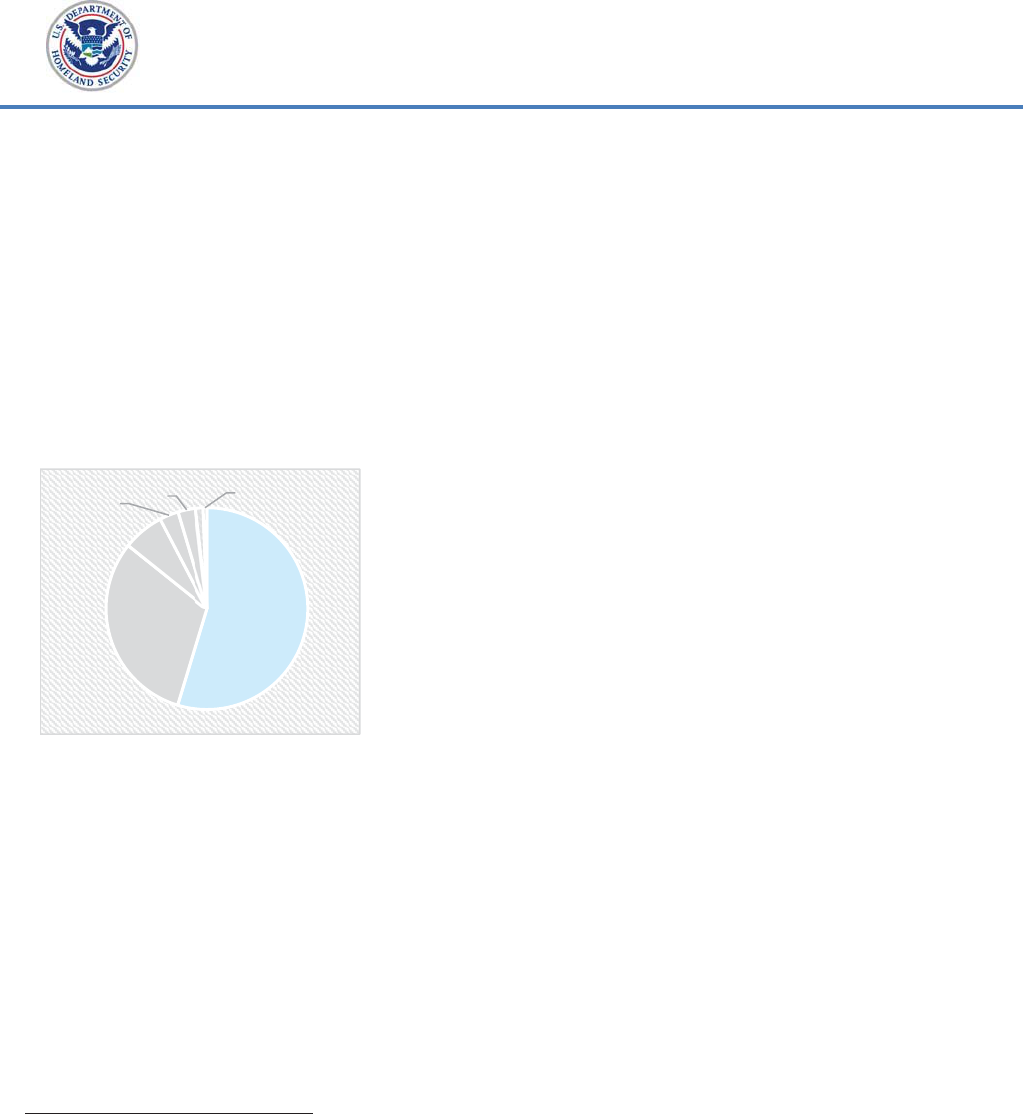

rights during the removal process. As shown in figure 2, of the 3,053 aliens

with final orders of removal detained more than 90 days, 1,670 (55 percent)

had legal appeals pending.

Our case review and interviews with ICE

Legal Appeals: (1,670 Cases)

Source: OIG

55%

31%

6%

3%

3%

1% 1%

Figure 2: Legal Appeals

officers indicate it can take months for a

court to hear a detainee’s appeal. One reason

for such delays is that, according to the

Government Accountability Office (GAO),

there is a “significant and growing case

backlog” for immigration judge hearings for

detainees.

13

GAO reported that immigration

court staffing gaps, current caseload

prioritization, the growing use of

continuances, and increased appeals to

higher courts contribute to the backlog.

According to GAO, at the start of FY 2015,

immigration courts had a backlog of about

437,000 cases pending and the median pending time for those cases was 404

days. As shown in appendix C, of the 490 detainees in our case review whose

appeals were denied, 231 (47 percent) were detained longer than 6 months

before they were repatriated. In addition, of the 96 detainees granted a form of

relief from repatriation, 43 (45 percent) were detained longer than 6 months

before they received a decision.

12

The basis for a detainee’s legal appeal or other challenge, and in what legal jurisdiction the

detainee files the appeal, determines whether ICE is required to allow the detainee to remain in

detention until the appeal is decided (stay removal). For example, if the detainee was ordered

removed in absentia (8 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) § 1003.23(b)(4)(ii)), or requests

protection under the Violence Against Women Act (8 U.S.C. § 1229a(c)(7)(C)(iv)), ICE cannot

remove the detainee until the claim is resolved. A motion to stay and a petition for review, in

some Circuit Courts, stays removal. Even if a stay of removal is not required, ICE can, at its

discretion, continue to detain the alien until the appeal is decided (8 U.S.C. § 1231(c)(2)).

13

GAO, Immigration Courts: Actions Needed to Reduce Case Backlog and Address Long-Standing

Management and Operational Challenges, GAO-17-438, June 2017

www.oig.dhs.gov 5 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Examples from our electronic case file review of removals delayed due to legal

appeals include:

x A Guatemalan national appealed an immigration judge’s decision to deny

temporary international protection. The appeal court remanded the case

to the immigration judge to reconsider. The immigration judge

rescheduled the hearing several times, then denied the claim. The

detainee appealed this decision and the appeal was still pending at the

time of our case review. This detainee has been in custody for more than

3 years.

x A Mexican national filed a petition with a Circuit Court for the review of

a removal decision. After the petition was denied, ICE transferred the

detainee to a new location, which was also in a new court jurisdiction, in

preparation for a repatriation flight. While waiting to be repatriated, the

detainee filed a request to reconsider the decision with the immigration

court where he had originally been detained. When the request was

denied, the detainee filed a new petition with the Circuit Court with

jurisdiction over the area where he had been staged for removal. At the

time of our review, the petition was still pending and this detainee had

been in custody for more than 3 years.

Overall, delays due to legal appeals or challenges may lead to aliens with final

orders of removal being held in detention for as long as 3 years, as evidenced in

the previous examples. Although legal appeals are an exception to the 90-day

clock, the prolonged detention imposes considerable costs on ICE. For example,

in FY 2017, ICE paid facilities detaining aliens approximately $100 per day, per

detainee.

14

Therefore, detaining an alien for 3 years costs ICE about $109,500.

Foreign Governments’ Inconsistent Cooperation on Repatriation Travel

Delays and Prevents Removals

Foreign governments’ cooperation with the repatriation of their nationals is

vital for achieving removals. Although repatriations to most countries happen

without significant delays, more than 30 countries present challenges to obtain

travel documents. In some instances, foreign governments do not conduct

timely interviews with detainees or notify ICE when additional information is

required to facilitate travel, delaying removals. Even though increased

14

According to GAO, ICE has difficulty estimating the actual cost of detention. ICE estimates a

rate of $132.59 per day per detainee, but GAO concludes this could be an underestimate. Our

estimate uses $100 per detainee because the most expensive beds — for families and detainees

requiring hospitalization — are under-represented in our case review. See GAO, Immigration

Detention: Opportunities Exist to Improve Cost Estimates, GAO-18-343, April 2018.

www.oig.dhs.gov 6 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

diplomatic engagement has improved cooperation on removals, some foreign

governments still fail to provide flight approvals or travel documents in time,

causing removal cancellations or delays. In some cases, countries simply do

not have the resources or infrastructure to assist ICE with required document

requests. Despite these factors lying outside of ICE’s control, they do not stop

the 90-day clock for removals.

Inability to Obtain Travel Documents from Foreign Governments Obstructs

Repatriation

Although a combination of increased diplomatic engagement with

uncooperative governments and a demonstrated willingness of the United

States to impose visa sanctions has increased foreign governments’

cooperation, some countries remain unwilling to provide travel documents.

This lack of cooperation, in essence, prohibits ICE removals to such countries.

Other countries lack bureaucratic infrastructure and resources to make

citizenship determinations quickly and issue travel documents for repatriation.

In other cases, the citizenship of detainees cannot even be established.

15

These

barriers to removals result in ICE releasing detainees, which in some cases can

endanger public safety, as our previous work has shown.

16

As figure 3 indicates, 948 of the 3,053

Travel Documents: (948 Cases)

Source: OIG

55%

31%

6%

3%

3%

1%

1%

Figure 3: Travel Documents

detainees (31 percent) in our case review

could not be removed because their travel

document requests were still pending.

With limited exceptions, if ICE is unable

to obtain a travel document for a detainee

within 6 months and there is no prospect

of obtaining one in the near future, the

15

For example, some detainees, such as Palestinians, were born stateless, and others became

stateless when countries such as the former Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, and Sudan

fragmented.

16

A Haitian national, Jean Jacques, previously convicted of attempted murder and subject to a

final order of removal, was released from ICE custody after repeated attempts to secure a travel

document from Haiti and killed another individual. See DHS OIG, Release of Jean Jacques from

ICE Custody, June 16, 2016.

www.oig.dhs.gov 7 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

detainee must be released.

17

Our case review indicates that ICE eventually

released 22 Chinese, 287 Cubans, 34 Eritreans, 21 Laotians, and 10

Vietnamese — detainees from countries considered uncooperative.

Foreign governments, with limited exceptions, require a passport or temporary

travel permit to accept their nationals back into the country.

18

Hence, ICE

needs to obtain such travel documents to repatriate aliens. El Salvador,

Guatemala, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic, issue travel documents

through an online ICE data system known as eTD (electronic Travel

Document), and Mexico does not require travel documents for repatriations on

the land border. In FY 2017, removals to these five countries accounted for

205,540 of ICE’s 226,119 removals (91 percent). Other foreign government

requirements for travel documents vary widely and the travel document

issuance can be cumbersome. For example, some countries require:

x an in-person consular interview with the detainee, at the country’s

consulate in the United States;

19

x identification documents, such as a national identity card or an expired

passport; or

x additional checks of paper-based records, such as birth certificates or

baptismal records, typically buried in immigration files or only available

at the detainee’s place of birth.

Because foreign governments do not issue travel documents without confirming

the identity and citizenship of the alien, ICE works with the detainees to collect

evidence of their citizenship to prepare a request for a travel document.

Although we heard that generally detainees disclose who they are, ICE

deportation officers described some cases when detainees provide numerous

identities or are unsure of their country of origin. Establishing identities of

such detainees complicates preparations for their repatriation. Examples from

our electronic case file review of removals delayed due to travel document

issues include:

17

Zadvydas v. Davis, 533 U.S. 678, 701 (2001) (holding that an alien with a final removal order

cannot be detained longer than 6 months unless there is a significant likelihood of removal in

the reasonably foreseeable future); see also Clark v. Martinez, 543 U.S. 371, 378 (2005)

(extending Zadvydas to inadmissible aliens). See DHS OIG’s prior report ICE’s Compliance With

Detention Limits for Aliens With a Final Order of Removal From the United States, OIG-07-28, for

information on the limited exceptions to this release requirement for public health and national

security cases.

18

ICE maintains country-specific guidelines on its intranet, which are based on the laws of

these governments and any formal and informal agreements between the United States and the

foreign government.

19

Some consulates are hours away from detention facilities and require ICE to make long trips

with detainees to facilitate those interviews.

www.oig.dhs.gov 8 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

x An Eritrean who was a registered sex offender had immigrated as a child

and did not have Eritrean identity documents or fluency in any language

spoken in Eritrea which, in some cases, can serve as evidence of

citizenship. Although the Eritrean government interviewed him, they

were unable to verify citizenship and ICE released him from detention.

x A Cambodian was detained for 2 months in Alabama while waiting for a

consular interview to determine citizenship. During that time, Cambodia

was not conducting interviews anywhere in the United States. The

consulate in California agreed to interview him and ICE flew him to

California. Several months later, the Cambodian government still had not

made a decision on whether to issue the detainee a travel document.

Increased Diplomatic Engagement Improves Cooperation on Removals

International standards require governments to issue travel documents to their

citizens within 30 days.

20

In 2015, the State Department and ICE increased

diplomatic engagement to improve cooperation on repatriations. The State

Department prioritized travel document issuance in bilateral relations while

ICE has centralized the travel document request process at headquarters for

the most challenging countries.

21

Between 2016 and 2018, the State

Department and DHS also escalated the use of visa sanctions, imposing them

on seven countries.

22

Most DHS officials we interviewed agreed that the combination of increased

diplomatic engagement and a demonstrated willingness to impose visa

sanctions has increased cooperation from most countries.

23

Between 2015 and

2018, the number of both uncooperative and at risk of noncompliance

countries — countries that do not issue travel documents or accept

20

International Civil Aviation Organization Annex 9, Chapters 5.26 through 5.29, set timeliness

standards for governments to repatriate their nationals. However, not all countries have signed

this Annex.

21

ICE Removal and International Operations officers at headquarters manage consular

relations and travel documents requests for Cambodia, Cameroon, Cuba, Dominica, Eritrea,

Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Haiti, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Kosovo, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania,

Palestine, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Vietnam.

22

In 2016, DHS imposed sanctions on the Gambia (the sanctions were later lifted). In 2017,

DHS imposed sanctions on Cambodia, Eritrea, Guinea, and Sierra Leone. In 2018, DHS

imposed sanctions on Burma and Laos, and lifted sanctions on Guinea.

23

Of the four countries sanctioned in FY 2017, Cambodia and Eritrea did not respond to

sanctions to increase cooperation.

www.oig.dhs.gov 9 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

repatriation flights — decreased considerably, as shown in table 1. Appendix D

lists the countries that fall within these categories.

Table 1: Countries’ Cooperation with Travel Document Issuance

Time Period

Uncooperative

Countries

At Risk of

Noncompliance Countries

July 2015 23 62

September 2016 20 55

September 2017 9 36

May 2018 9 24

Source: ICE

ICE Relies on Diplomatic and Logistical Coordination for Removal Flights

With the exception of 10 western hemisphere countries that accept routine

charter flights,

24

obtaining foreign government permission for repatriation

flights can delay removals. Foreign governments may require negotiations

before accepting charter flights or can limit the number of repatriations allowed

per month. Some foreign governments do not allow transit through their

countries, requiring ICE Air to take a more complex route. In other instances, a

foreign government authorizes a charter flight, but does not issue travel

documents to the detainees or visas to the ICE Air flight crew in time to board

the flight. As shown in figure 4, our case

Flights and Escorts: 201 Cases

(Flight) and 37 Cases (Escorts)

Source: OIG

55%

31%

6%

3%

3%

1%

1%

Figure 4: Flights and Escorts

review indicated that 201 of the 3,053

detainees (6 percent) had a travel

document and were waiting for a

repatriation flight, and the removals of 37

(1 percent) were delayed because a flight

escort needed to be arranged for a

commercial repatriation flight.

ICE typically repatriates detainees via

charter flights, Special High Risk

Charters, or commercial flights, with the

exception of most Mexican nationals, who

are repatriated across the land border.

Although ICE does not publish official

statistics on the number of repatriations

24

ICE Air Operations conducts routine repatriation flights to Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador,

Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, and Nicaragua. ICE Air

shares its flight manifests with the repatriation country and does not have difficulty securing

landing permission for each flight.

www.oig.dhs.gov 10 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

by air, our analysis of ICE Air data indicated that more than 80,000 detainees

were repatriated on ICE Air’s routine charter flights in FY 2017. In addition,

based on our analysis of ICE Air reports, detainee removals included:

x 1,443 by Special High Risk Charter flights;

x 6,155 by commercial flights without an ICE escort; and

x 2,133 by commercial flights with an ICE escort.

With the exception of the 10 western hemisphere countries that have agreed to

accept routine charter flights, ICE staff need to seek approval from foreign

governments for repatriation flights. Specifically, for commercial flights they

may need to obtain approval of flight itineraries, and for charter flights they

must coordinate the flight paths. When no direct commercial flights are

available, ICE works with foreign governments for permission to escort a

detainee through a transit country.

Although ICE tries to arrange charter flights within a month of identifying the

need, some Special High Risk Charters require months to negotiate. In

addition, if transit or repatriation countries limit the number of detainees who

can be placed on flights, lower priority detainees may be held in detention

longer.

Foreign governments must also issue travel visas for ICE deportation officers

performing flight escort missions. When a travel visa is required, ICE has a

limited period in which to obtain one but foreign governments do not always

issue visas in a timely manner, resulting in delayed removals on occasion.

Examples from our electronic case file review of removals delayed due to flight

coordination challenges include:

x An ICE field office secured a travel document for an Iraqi who was

hospitalized and required a medical escort for removal. Because the flight

needed to transit through Turkey, from which it may take several weeks

to obtain clearance, ICE Air scheduled the flight for 6 weeks later, adding

to the expense of extended hospitalization.

x An ICE field office reported that it needed to reschedule flights repeatedly

through Morocco to Sub-Saharan Africa because Morocco limits the

number of transit flights, and higher priority removals were scheduled

first, leaving other aliens eligible for repatriation in detention.

www.oig.dhs.gov 11 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Detainees’ Failure to Comply with ICE Repatriation Efforts Delays

Removal

Detainees can delay removal by failing to comply with the removal process.

25

For example, detainees may conceal country of citizenship, refuse to request a

travel document, or resist boarding a repatriation flight. Such cases typically

require additional time and effort because ICE deportation officers need to

obtain evidence of the detainee’s citizenship without his or her cooperation by

researching the alien’s statement at apprehension, documents in the

immigration file, border crossing history, and conducting interviews with

relatives. ICE can also request that the Department of Justice consider

criminal prosecution.

26

Failure to Comply: (93 Cases)

Source: OIG

55%

31%

6%

3%

3%

1%

1%

Figure 5: Failure to Comply

As shown in figure 5, in our case review,

only 93 of the 3,053 detainees (3 percent)

failed to comply with repatriation efforts for

90 days or longer. Detainees cannot obtain

release from detention solely by failing to

cooperate with the removal process. By law,

failure to comply stops the 90-day removal

clock, and ICE can detain indefinitely,

though at considerable expense.

27

Examples from our electronic case file

review include:

x In 2013, ICE obtained a travel document and scheduled a flight for

a detainee ordered removed to Pakistan, but the detainee refused

to board the flight. When Pakistan interviewed the detainee for

another travel document, the detainee claimed he was Somali. The

detainee told a third party he planned to renounce both Pakistani

and Somali citizenship and then request release. The detainee

renounced his Pakistani citizenship and did not provide ICE

sufficient information to request a travel document from Somalia.

In 2017, Pakistan refused to issue a travel document, saying the

detainee had renounced his citizenship and was Somali. In 2018,

the detainee agreed to rescind his revocation of citizenship, and the

25

8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(1)(C)

26

8 U.S.C. § 1253(a). Federal prosecutors from a United States Attorney’s Office may charge an

alien criminally if the alien fails to assist with, or prevents, removal.

27

8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(1)(C)

www.oig.dhs.gov 12 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

request was pending with the Pakistani government. This alien has

been in custody for more than 4 years.

x In 2014, an Indian national requested asylum after being

immediately detained upon arrival in the United States. The

asylum claim was denied in early 2015, and the detainee was

scheduled for removal, but he refused to sign a travel document

request. In case comments, ICE wrote that the detainee said he

“didn’t mind to remain in custody a long time as he does not want

to go back to India.” In 2018, ICE received a travel document from

India without the detainee’s cooperation. The next charter flight to

India was full, so the detainee was scheduled for a commercial

flight a month later, but the removal was further delayed. This

alien has been in custody for more than 3 years.

Serious Medical Conditions May Delay the Repatriation Process

Detainees’ medical and mental health conditions can complicate each stage of

the removal process including legal appeals, issuance of travel documents, and

arranging repatriation transport. For example, detainees with serious physical

illnesses might require continuances on their legal appeals. In addition, some

foreign governments will not issue travel documents for detainees with medical

conditions until they can verify that the detainee has access to suitable care,

for example dialysis. ICE must also complete treatments for any infectious

diseases, such as tuberculosis, and stabilize any medical conditions, such as

cardiac rehabilitation, before arranging transportation. It may also be difficult

for deportation officers to determine the line between failing to cooperate with

the removal process and being unable to do so.

Medical: (19 Cases)

Source: OIG

55%

31%

6%

3%

3%

1%

1%

Figure 6: Medical

As shown in figure 6, medical conditions

represented only 19 of the 3,053 detainees

(less than 1 percent) in our case review.

However, our case review methodology

may under-represent the number of

detainees with medical conditions, as ICE

or the immigration courts could decide

well before 90 days that continued

detention is not optimal. For example,

detainees with serious mental health

issues may require legal representation,

and DHS or an immigration judge may

www.oig.dhs.gov 13 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

determine that continued detention is not in the detainee’s best interest and

release the detainee on bond.

28

Removing detainees with medical and mental health conditions may be delayed

because of special requirements. For example, some foreign governments will

not issue travel documents for detainees with mental health conditions until

they can verify that the detainee has family and a place to stay. ICE may need

to arrange for a Special High Risk Charter, or for medical staff to accompany

ICE Deportation Officers escorting the detainee on a commercial flight. If ICE

cannot obtain a travel document, or the detainee cannot assist with the

removal process, the detainee may be released. Examples from our electronic

case file review include:

x A Mexican national was referred to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration

Services (USCIS) for an interview to determine whether the detainee

required international protection. USCIS reported that the detainee was

unresponsive to interview questions. A medical screening suggested there

was an unspecified psychosis. USCIS determined the protection claim

had merit and referred the case to an immigration judge. After several

continuances, the immigration judge released the detainee on bond.

x A Cuban national diagnosed with mental health issues repeatedly

attacked detention facility staff and other detainees. He was placed in

segregation on several occasions, and local staff recommended he be

transferred to a facility that could handle his mental health issues.

Before a transfer could be effected, ICE released him into the community

because Cuba did not provide ICE with a travel document for removal.

Internal Challenges with ICE Staffing, Technology, and

Accuracy of Metrics Limit Efficiency of Removals

Although many of the barriers to removal are external, internal ICE challenges

with staffing and technology also diminish the efficiency of the removal

process. ICE’s detained docket has high staff turnover, making it difficult to

maintain the expertise needed to manage complex final order cases effectively

and accomplish removals. Limited staffing affects the quality of removal

paperwork ICE submits, causing potential delays in removals. In addition, ICE

28

An April 2013 ruling in Franco v. Holder, 10-cv-2211 (C.D. Cal. Apr. 23, 2013) established

the right to representation for detainees with serious mental disorders that render them unable

to represent themselves. The ruling, which applies in California, Arizona, and Washington

State, also requires a custody redetermination hearing for aliens with a serious mental disorder

who have been detained longer than 180 days.

www.oig.dhs.gov 14 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Air manages repatriation flights with a cumbersome, labor-intensive manual

process, which can result in detainees who are eligible for repatriation missing

flights. Finally, ICE metrics for determining country cooperation lack an

objective methodology, potentially resulting in visa sanctions on otherwise

cooperative countries.

Insufficient ICE ERO Staffing for Detained Docket Causes Delays in Removals

During our interviews with field office staff, we heard that ICE does not

adequately staff the detained docket and has difficulty recruiting and retaining

officers to perform this function. Some field offices’ workloads are so large that

the staff cannot obtain detainees’ identity information or produce quality travel

document applications timely, which can delay or prevent removals.

29

The ICE mission of monitoring the status of detainees with final orders of

removal and managing their repatriation efficiently is very challenging. Yet, ICE

ERO could not provide any staffing plans recommending optimal workloads for

the deportation officers working detained dockets; hence, the staffing resources

24 ICE field offices devote to detained dockets vary considerably. We

interviewed officials from 12 ICE field offices and most said ICE needs more

staff dedicated to these tasks.

Many of the ICE ERO staff we interviewed said it is difficult for a field

deportation officer to manage a caseload of more than 75 detainees effectively,

especially when the cases include countries with complex travel document

requirements. However, of the 12 field offices we engaged during our review, 5

have deportation officers with heavy caseloads, managing 100 or more cases

each.

For example, we encountered 2 field offices where deportation officers have

more than 120 complex cases

30

each. One officer we interviewed maintained

about 500 cases when he had to step in for another officer while also working

his own caseload. An ICE headquarters employee we spoke with, who

conducted a quality assurance review in the field, described finding an

egregious timeliness issue where it was taking a deportation officer more than

90 days to prepare a travel document request that should be done within the

first 7 days. The headquarters employee then noticed that the officer had a

caseload of 230 detainees, which he opined was unmanageable.

29

Because ICE’s data system is not designed to track causes for delays, we were unable to

analyze the extent to which poor quality of documentation delays repatriation.

30

Complex cases refer to managing removals of detainees who are from countries other than

those western hemisphere countries which do not require travel documents.

www.oig.dhs.gov 15 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

ICE headquarters and field office staff reported that heavy workloads held by

some field deportation officers lead to the inconsistent quality of administrative

paperwork they prepare, resulting in errors that delay removals. Our review

confirmed that in some instances:

x Travel document requests were missing required paperwork, such as

evidence of a final order of removal or criminal convictions.

x Detainees’ photos were of such poor quality that they could not be

used and basic biometric information, such as fingerprints or hair

and eye color, were not included.

x Detainees have missed repatriation flights because their medical

paperwork was missing or incomplete and their medications were not

provided.

x Consulates have rejected some travel document requests as incomplete

or inaccurate because initially deportation officers did not thoroughly

check the detainees’ immigration files for missing information or talk to

relatives to obtain it.

ICE ERO has experimented with how it assigns work, attempting to alleviate

staffing issues and improve removal operations, but there are no easy fixes.

ICE ERO field offices that allowed officers to rotate from the detained docket

after 6 months or 1 year observed that such short-term rotations do not give

the officers sufficient time to become proficient in detained docket case

management. On the other hand, field offices that keep staff on the detained

docket long-term or indefinitely reported difficulty recruiting and retaining

staff, and maintaining morale. ICE ERO field offices’ supervisors and officers

we interviewed reported that working the detained docket is considered more

challenging and less satisfying than performing arrests or tracking fugitive

aliens.

ICE Officers Performing Arrests Need Training on Removal Process

Missed opportunities by ICE apprehending officers to locate and secure identity

documents — such as passports or birth certificates — during initial arrest

may delay the removal process. ICE deportation officers tasked with removals

explained that ICE arresting officers do not consistently ask questions, such as

alien’s place of birth or country of origin, or collect the documents, such as

passport or identification cards, vital to the removal process. We were told that

ICE officers tasked with arresting aliens may not have a deep understanding of

www.oig.dhs.gov 16 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

immigration laws or they may lack experience with removal operations and do

not always “keep removal in mind.”

As shown in appendix E, deportation officers who work the detained docket are

trained to consult as many sources as possible to obtain evidence of a

detainee’s identity and citizenship. Therefore, ICE must communicate to

apprehending officers the importance of obtaining documentary and

testimonial evidence from aliens during arrests as doing so improves the

likelihood and efficiency of removal.

ICE Air Needs to Enhance Technology for Efficient Repatriation

ICE Air currently manages the complex scheduling of repatriation flights using

manual processes. Without a web-based reservation system, organizing flights

and determining which aliens can be repatriated is a cumbersome, labor-

intensive process occasionally resulting in missed flights for detainees who are

eligible for repatriation.

In FY 2017, ICE Air coordinated the removal of 8,288 aliens via commercial

flights and the removal or transfer of 181,317 aliens via charter flights. Despite

this volume and the complexities of arranging flights, as previously discussed,

ICE Air uses a Microsoft Access database to create flight manifests, and

Microsoft Outlook and Excel to track and manage flights.

ICE Air manually adds and removes detainees from flights based on the highest

priorities for repatriation, legal appeals which stay removal, medical

emergencies, and other logistical considerations. ICE Air emails changes to the

flight manifests to all field offices, sometimes sending two or more email

updates per day, per flight. The 24 field offices must then manually review each

revised manifest to identify which of their detainees can be repatriated on the

next scheduled flight. The field offices have to drive or fly their detainees to

domestic staging sites where ICE Air collects and prepares them for the

international flights. Therefore, one international flight may involve multiple

domestic stops that need to be coordinated as well. In some instances, field

offices have been notified that their detainee was scheduled for repatriation

only to find out on a new manifest that the detainee is no longer on the charter

passenger list, resulting in a missed flight for such detainees. In addition, ICE

Air officials reported that although Special High Risk Charters can take weeks

or months to arrange, they are often not full, even when field offices have aliens

who have valid travel documents and are eligible for removal, causing detainees

to remain in custody until further flights can be coordinated.

www.oig.dhs.gov 17 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

ICE acknowledges that the lack of a technological infrastructure is a problem,

but only has plans for a limited upgrade — moving the Access database to a

secured cloud environment. A web-based flight reservation system could

reduce the time ICE Air and ICE field offices spend manually creating and

tracking flight manifests, and could allow field officers to focus more on the

administrative paperwork for the detained docket.

ICE Needs to Improve Its Metrics and Methodology Related to Visa Sanctions

ICE has metrics to track the timeliness of travel document issuance; however,

they do not account for delays in the removal process that are outside of

foreign governments’ control. Although not completely reliable, ICE uses these

imprecise metrics to inform significant diplomatic decisions, such as

recommending visa sanctions.

In the 2017 Memorandum of Understanding, DHS and the State Department

agreed on six measures of cooperation tied to travel document issuance,

acceptance of repatriation flights, and timeliness of responses to requests for

travel documents and flights.

31

However, ICE’s data system lacks the capacity

to track compliance with these measures. Specifically, ICE’s metrics do not

account for travel document applications returned to ICE by consulates

because they are inaccurate or incomplete, nor do they capture logistical flight

delays. Also, the metrics do not identify the date of a travel document request

or the date a travel document was issued or denied.

In an effort to establish an objective measure of countries’ cooperation, ICE

introduced the Removal Cooperation Initiative (RCI) Tool. The RCI Tool

identifies countries as cooperative, at risk of noncompliance, or uncooperative

based on:

x how long it takes on average to remove aliens;

x how many aliens must be released because they cannot be removed;

x the country’s willingness to conduct interviews; and

x the country’s willingness to accept charter flights.

Nonetheless, current metrics do not provide an accurate assessment of a

country’s cooperation status, failing to account for significant steps in the

removal process outside the control of foreign governments and ICE. For

example, the timeliness metric used to identify how long it takes to remove

aliens does not exclude the time for legal appeals or failure to comply with

31

Memorandum of Understanding Between the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the

U.S. Department of State Concerning the Removal of Aliens, August 16, 2017, Section IV

www.oig.dhs.gov 18 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

removal, which, as described earlier, can cause significant delays. ICE

manually removes such outliers as delays for legal appeals, resulting in

potentially incorrect assessments of country cooperation. Despite these

limitations, ICE currently uses the statistics from the RCI Tool to assess

countries’ cooperation to make decisions on visa sanctions.

In addition to using imprecise statistics in its assessments, ICE’s conclusions

for determining which countries to sanction and when to lift sanctions are not

clear. We did not find a methodology explaining what circumstances prompt

ICE to disregard or “override” the RCI Tool score for some countries, in essence

modifying their status on cooperation. For example, we heard that some

countries may have been scored as at risk of noncompliance in the RCI Tool,

yet were sanctioned without first being categorized as uncooperative.

Conversely, countries categorized as cooperative have not had sanctions

lifted.

32

Finally, ICE does not share its rationale for imposing and lifting

sanctions with the DHS Office of Policy and the State Department, although

both agencies are involved in diplomatic engagements.

There are valid reasons to use sanctions selectively as the United States has

complex geopolitical relations with some countries. In addition, some countries

lack the institutional capacity to issue travel documents quickly or consistently

and sanctions might not have the desired effect of improved cooperation.

However, a methodology for determining which countries are sanctioned and

what conditions must be met to lift sanctions, as well as better information

sharing with ICE’s partners, could help both DHS and the State Department

engage foreign governments more effectively.

ICE Needs to Improve the eTD Module for Monitoring Country Cooperation

The ICE data system known as ENFORCE Alien Removal Module contains the

eTD module,

33

which can be used to monitor the time it takes for countries to

issue travel documents. ICE has improved the eTD module’s ability to generate

real-time reports from field offices on the status of travel document requests

from any country as well as numbers of travel documents issued and the

issuance rates by country and consulate. However, ICE does not generate

official statistics from the eTD module.

32

In 2017, Guinea and Sierra Leone were sanctioned even though they were just categorized as

at risk of noncompliance. These countries are now listed as cooperative, but continue to be

under sanctions. Meanwhile countries that are consistently categorized as uncooperative,

including Vietnam, Cuba, China, and Iran, have not been sanctioned.

33

ENFORCE is not an acronym. The eTD module refers to the electronic travel document

module.

www.oig.dhs.gov 19 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

In 2008, eTD was upgraded specifically to process and track the status of all

travel document requests from all countries, with the exception of Canada and

Mexico. ICE internal guidance from 2008 requires that all new travel document

requests for aliens must be put through the eTD system. For all countries, with

the exception of Mexico, ICE officers should enter the dates of travel document

issuance into eTD; only a few countries can currently approve travel

documents through eTD. Travel document issuance is a key element in

determining countries’ cooperation, but ICE is not using eTD to monitor

whether countries routinely issue travel documents within the 30-day

requirement. The information in the eTD module could enable ICE to more

accurately distinguish delays caused by foreign governments’ lack of

cooperation from the delays outside other countries’ control.

Recommendations

We recommend the Executive Associate Director for Immigration and Customs

Enforcement, Enforcement and Removal Operations:

Recommendation 1: Develop a staffing model that assigns sufficient

deportation officers to the detained docket to actively manage post-order

custody cases.

Recommendation 2: Develop training for all Enforcement and Removal

Operations staff assigned to alien apprehensions, highlighting the importance

of obtaining identity documents and complete and accurate information at

apprehension, and how such documents and information affect the removal

process.

We recommend the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Director:

Recommendation 3: Develop a web-based flight management and tracking

system to support the domestic air transfer and international removal air travel

operational demands of Enforcement and Removal Operations.

Recommendation 4: Develop written documentation of recommendations and

justifications for imposing, retaining, and lifting visa sanctions.

Recommendation 5: Implement the use of an electronic system comparable

to, or more accurate than, eTD as a source for official statistics, to improve the

measures of cooperation with travel document requests.

www.oig.dhs.gov 20 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

OIG Analysis of Management Comments

We have included a copy of ICE’s Management Response in its entirety in

appendix B. We also received technical comments from ICE and incorporated

them in the report where appropriate. We consider all of the recommendations

to be resolved and open. A summary of ICE’s responses and our analysis

follows. ICE concurred with all five recommendations.

ICE Response to Recommendation 1: ICE concurred with the

recommendation. ICE officials stated that ICE would review the workload of its

deportation officers, and determine an ideal staffing level to manage post-order

custody cases. ICE officials noted that the staffing model would need to evolve

with operational trends, and that even the best staffing model may not achieve

the goals outlined in this report. ICE anticipates completing these actions by

October 30, 2019.

OIG Analysis: We consider these actions responsive to the recommendation,

which is resolved and open. We will close this recommendation when we

receive documentation that ICE has developed a staffing model for managing

its post-order custody cases. We recognize that the staffing model will continue

to evolve with operational trends, and that factors external to the staffing

model, such as budget and position vacancies, may affect staffing.

ICE Response to Recommendation 2: ICE concurred with the

recommendation. ICE officials stated that ICE conducts an annual training at

every field office. Although the training is open to all officers, typically only

detained-docket officers attend. ICE officials said they would ensure that all

future trainings are attended by all officers, with an increased emphasis on

attendance of those responsible for conducting alien apprehensions and non-

detained case management. ICE anticipates completing these actions by April

30, 2019.

OIG Analysis: We consider these actions responsive to the recommendation,

which is resolved and open. We will close this recommendation when we

receive documentation that ICE has instructed officers who do not work on

detained cases that they should attend the annual training.

ICE Response to Recommendation 3: ICE concurred with the

recommendation. ICE officials stated that ICE plans to develop a transportation

management system that will be integrated into ICE’s case and removal

management systems. ICE officials noted that the focus of the system would be

on travel management, but that the system would also support financial

www.oig.dhs.gov 21 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

management and enable ICE to quantify its workload. ICE officials stated that

the first milestone would be to submit a funding request in the February 2019

budget development cycle. ICE anticipates completing these actions by

December 31, 2020.

OIG Analysis: We consider these actions responsive to the recommendation,

which is resolved and open. We will close this recommendation when we

receive documentation that ICE has received a final decision on its request to

fund the transportation management system.

ICE Response to Recommendation 4: ICE concurred with the

recommendation. ICE officials stated that ICE has the authority to impose visa

sanctions for any incident of lack of cooperation. ICE noted that it conducts

monthly meetings with the Department of States and the Department of

Homeland Security Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans regarding cooperation.

ICE officials also stated that statistics are one of many factors considered in

the visa sanction process. ICE stated that going forward, following each

monthly meeting, it would send meeting notes — documenting the next steps

to take for each country — to the Department of State and the Office of

Strategy, Policy, and Plans. ICE anticipated completing these actions by

February 28, 2019.

OIG Analysis: We consider these actions responsive to the recommendation,

which is resolved and open. We will close this recommendation when we

receive documentation that ICE has submitted to the Department of State and

the Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans meeting notes documenting the next

steps to take for each country for four consecutive months.

ICE Response to Recommendation 5: ICE concurred with the

recommendation. ICE officials stated that ICE will prioritize the development

and deployment of an electronic system as a source for official statistics

regarding travel document decisions. The initial requirements process is

scheduled to be completed by June 30, 2019, and the initial rollout by June

30, 2020. ICE anticipates completing these actions by October 31, 2020.

OIG Analysis: We consider these actions responsive to the recommendation,

which is resolved and open. We will close this recommendation when we

receive documentation that ICE has begun publishing official statistics

regarding travel document decisions from its electronic system.

www.oig.dhs.gov 22 OIG-19-28

A

A

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix A

Objective, Scope, and Methodology

The Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General (OIG) was

established by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law 107ï296) by

amendment to the Inspector General Act of 1978.

Our objective for this review was to identify barriers to repatriation of detained

aliens with final orders of removal. To achieve our objective, we reviewed ICE’s

policies, procedures, and guidance for removing detained aliens with final

orders of removal. We also reviewed available information from ICE’s data

systems, including data used in the RCI Tool, and data used for ICE’s official

statistics on removals. We assessed ICE’s quality assurance and oversight

programs, including memorandums reporting results of field site visits, ICE Air

feedback on common errors seen in travel packets, and ICE’s training and

guidance materials.

Using ICE data, we selected one staging facility and three field offices to visit

and observe the work performed on flight operations and the detained docket,

based on a range of factors including facility type and complexity of removals.

We also conducted in person or telephonic interviews with personnel from ICE

Air Operations, ICE Headquarters Removal and International Operations,

supervisory deportation officers and deportation officers at numerous field

offices throughout the United States. We also interviewed officials from

Department of State, DHS Office of Policy, ICE Law Enforcement Systems and

Analysis Unit, ICE Office of the Principal Legal Advisor, and ICE Office of Chief

Information Officer.

To better understand what challenges removal operations of detained aliens

face, we took a snapshot of all aliens with final orders of removal in ICE

detention on December 13, 2017. We chose to review those cases where

detainees were held longer than 90 days for a total of 3,053 records. The ICE

deportation officer case comments were reviewed for the 3,053 records to

identify possible barriers that prohibited timely removal. We shared the alien

numbers of detainees from the snapshot with the ICE Law Enforcement

Systems and Analysis Unit to obtain the case disposition of those cases as of

March 24, 2018. The information in this report on case dispositions is based

on the information provided by ICE.

We conducted this review between March 2018 and July 2018 pursuant to the

authority of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, and according to

www.oig.dhs.gov 23 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

the Quality Standards for Inspections issued by the Council of the Inspectors

General on Integrity and Efficiency. We believe that the evidence obtained

provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based upon our

objectives.

www.oig.dhs.gov 24 OIG-19-28

C

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

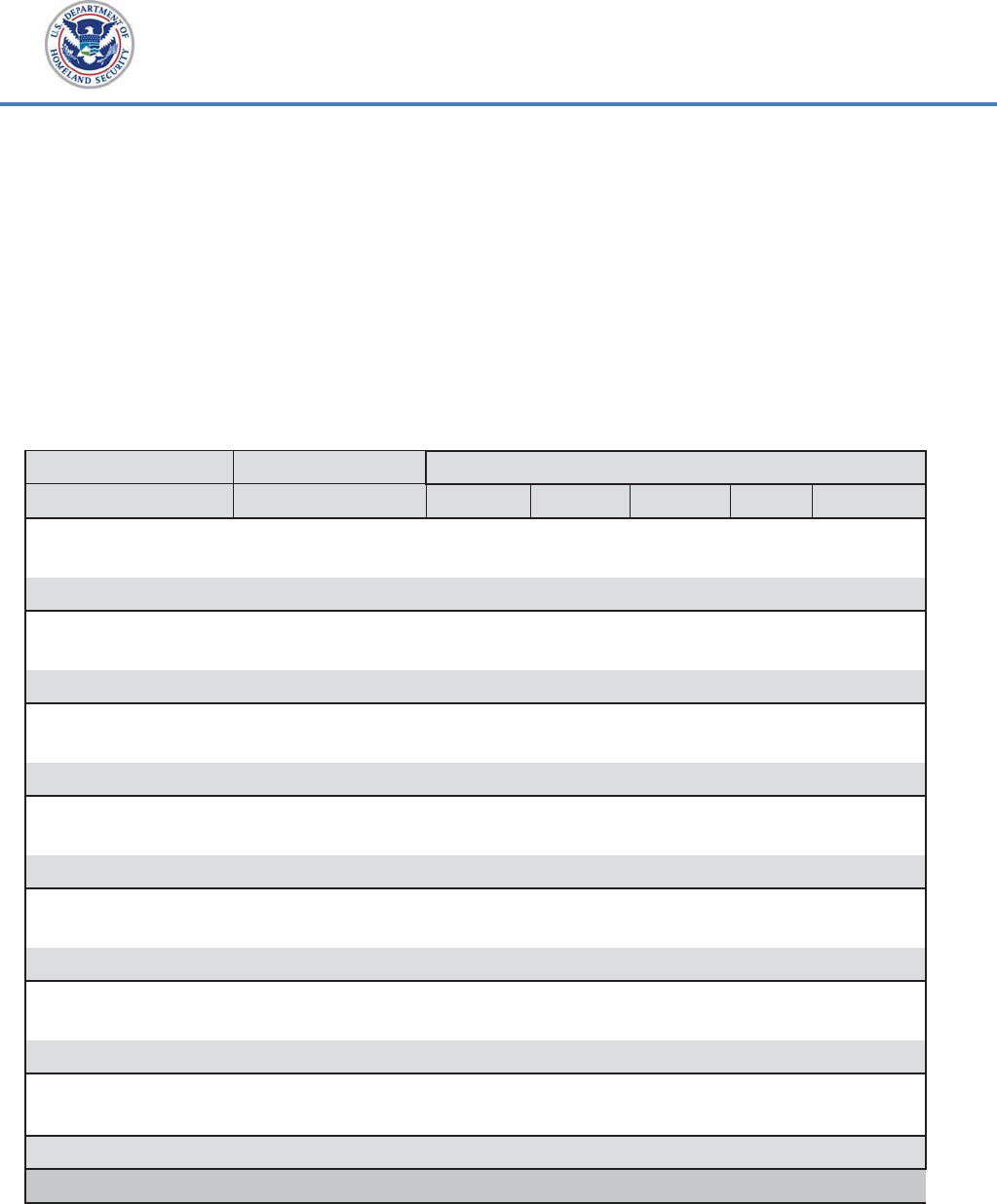

Appendix C

Results of Electronic File Case Review

We took a snapshot of all aliens with final orders of removal in ICE detention

on December 13, 2017. We asked ICE to provide us a case disposition for each

of the cases where the alien was held longer than 90 days as of March 24,

2018. Table 2 reflects our identification of delays or barriers to removal, and

ICE’s information on the status of each case.

Table 2: Snapshot Case Dispositions

Post Order Detention Barrier to Removal

Case Disposition as of March 24, 2018

Removed Detained Released Other Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91–180 Days

181+ Days

Total

91+ Days

Legal Appeals

Legal Appeals

Legal Appeals

Travel Document

Travel Document

Travel Document

Flight

Flight

Flight

Failure to Comply

Failure to Comply

Failure to Comply

Other

Other

Other

Escort

Escort

Escort

Medical

Medical

Medical

Total

259 387 132 34

231 468 131 28

490 855 263 62

126 151 260 10

100 126 157 18

226 277 417 28

82 37

0

2

55 23

0

2

137 60 0 4

14 14

0

1

15 46 2 1

29 60 2 2

20 12 7 16

8 11 2 9

28 23 9 25

21

0 0

2

13 1

0

0

34 1 0 2

3 3 2 0

4 5 2 0

7 8 4 0

951 1,284 695 123

812

858

1,670

547

401

948

121

80

201

29

64

93

55

30

85

23

14

37

8

11

19

3,053

Source: OIG Analysis of Aliens Detained Longer than 90 Days Post Final Order of Removal,

from ICE ENFORCE Alien Removal Module, ICE Law Enforcement Systems and Analysis case

disposition information as of March 24, 2018

www.oig.dhs.gov 28 OIG-19-28

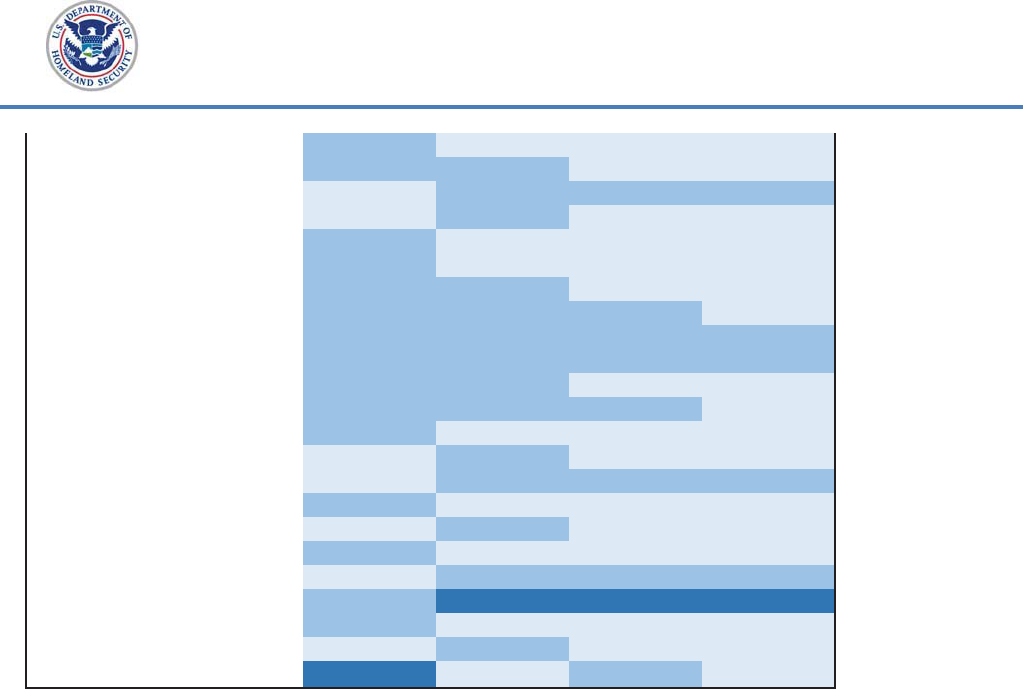

D

Uncooperative Uncooperative

ARON Other

Uncooperative Uncooperative

ARON Other

ARON

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix D

Countries’ Cooperation with Repatriation

July September September May

Country 2015 2016 2017 2018

Afghanistan Other Other

Albania Other Other

Algeria Uncooperative Uncooperative Other ARON

Angola Other ARON Other Other

Antigua Barbuda ARON ARON Other Other

Armenia ARON Other Other ARON

Azerbaijan Other ARON Other Other

Bahamas Other ARON Other Other

Bangladesh ARON ARON Other Other

Barbados ARON Other ARON Other

Belarus ARON ARON Other Other

Bermuda ARON Other ARON Other

Bhutan Other Other Other ARON

Bolivia ARON Other Other Other

Bosnia And Herzegovina ARON ARON Other Other

Brazil ARON ARON ARON ARON

British Virgin Islands Other ARON Other Other

Bulgaria

Uncooperative

Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Uncooperative

Uncooperative

Uncooperative Uncooperative

Other ARON Other Other

Burkina Faso Other

ARON ARON

Burma ARON

Burundi ARON ARON ARON

Cambodia ARON

Cameroon ARON Other Other Other

Cape Verde Uncooperative Other Other Other

Chad ARON ARON Other Other

China

Comoros ARON Other Other Other

Cuba

Czech Republic ARON Other Other Other

Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Democratic Republic Of The

Congo ARON Other Other Other

Dominica ARON ARON ARON ARON

Egypt

Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Other ARON ARON ARON

Eritrea

Estonia Other ARON Other Other

Ethiopia Other ARON ARON ARON

Fiji ARON Other Other Other

Gambia Other Other

Georgia Other Other

Ghana Uncooperative ARON ARON

Greece ARON Other Other Other

Grenada Other ARON Other Other

Guinea

Uncooperative Uncooperative ARON Other

www.oig.dhs.gov 29 OIG-19-28

Uncooperative Uncooperative

ARON Other

ARON

ARON ARON

ARON Uncooperative

ARON Other

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Guinea Bissau ARON Other Other Other

Haiti ARON Other Other Other

Hong Kong ARON Other Uncooperative Uncooperative

India Uncooperative Other Other Other

Indonesia ARON Other Other Other

Iran Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Iraq Uncooperative Uncooperative ARON ARON

Israel Other Other ARON ARON

Ivory Coast Uncooperative ARON ARON ARON

Jordan ARON ARON Other Other

Kazakhstan ARON Other Other Other

Kenya ARON ARON ARON ARON

Kosovo ARON Other Other Other

Kyrgyzstan ARON Other Other Other

Laos Other Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Lebanon ARON ARON Other ARON

Lesotho Other ARON Other Other

Liberia Uncooperative ARON Other Other

Libya Uncooperative ARON ARON Other

Lithuania ARON ARON Other Other

Macedonia Other ARON Other Other

Mali ARON Other

Martinique Other Other

Mauritania Uncooperative ARON Other

Moldova ARON Other Other Other

Mongolia ARON Other Other Other

Montserrat Other ARON ARON

Other

Morocco Uncooperative Uncooperative ARON Other

Namibia Other Other ARON ARON

Nepal ARON ARON Other Other

Niger Other ARON ARON Other

Nigeria Other Other ARON ARON

Norway Other ARON Other Other

Pakistan ARON ARON ARON ARON

Panama Other ARON Other Other

Papua New Guinea ARON Other Other Other

Paraguay ARON ARON Other Other

Qatar Other ARON Other Other

Republic Of Congo ARON ARON ARON Other

Romania Other ARON Other Other

Russia ARON Other Other Other

Rwanda Other ARON Other Other

Samoa ARON Other

Senegal ARON ARON

Serbia Other Other

Sierra Leone Uncooperative Uncooperative ARON Other

Slovakia Other ARON Other Other

Slovenia ARON Other Other Other

Somalia Uncooperative Uncooperative Other Other

South Sudan Uncooperative Uncooperative ARON Other

Sri Lanka ARON Other Other Other

www.oig.dhs.gov 30 OIG-19-28

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

St. Kitts Nevis ARON Other Other Other

St. Lucia ARON ARON Other Other

Sudan Other ARON ARON ARON

Suriname Other ARON Other Other

Sweden ARON Other Other Other

Syria ARON Other Other Other

Tajikistan ARON ARON Other Other

Tanzania ARON ARON ARON Other

Thailand ARON ARON ARON ARON

Togo ARON ARON ARON ARON

Tonga ARON ARON Other Other

Tunisia ARON ARON ARON Other

Turkey ARON Other Other Other

Turkmenistan Other ARON Other Other

Uganda Other ARON ARON ARON

Ukraine ARON Other Other Other

United Kingdom Other ARON Other Other

Uzbekistan ARON Other Other Other

Venezuela Other ARON ARON ARON

Vietnam ARON

Yemen ARON Other Other Other

Zambia Other ARON Other Other

Zimbabwe

Uncooperative Uncooperative Uncooperative

Uncooperative Other ARON Other

Legend: ʄ Uncooperative ʄ ARON (At Risk of Noncompliance) ʄ Other

Source: ICE

www.oig.dhs.gov 31 OIG-19-28

E

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix E

Travel Document Requests

Prior to submitting the travel document request to the embassy or consular

office, ICE staff interviews the alien to complete the Form I-217, Information for

Travel Document or Passport. The Form I-217 is the source document for

information necessary to complete the travel document request. It needs to be

thoroughly completed to avoid delays in the issuance of the travel document.

Complete travel document requests include but are not limited to:

x I-217 – Information for Travel Document or Passport

x Any available identity documents

x Charging Document

x Final Order of Removal

x I-205 – Warrant of Removal

x I-294 – Warning to Alien Ordered Removed or Deported

x I-296 – Notice to Alien Ordered Removed / Departure Verification

x Photograph(s)

Prior to submitting the travel packet, deportation officers must review the

country-specific Removal Guidelines posted on the ICE website (Removal and

International Operations Guidelines) to ascertain requirements for travel

document requests. Following are examples of different requirements countries

might have for travel documents:

x Travel itinerary

x Return of expired passport

x Number of photographs

x Processing fee

x Required consular interview

x Evidence the alien has been ordered removed

x Foreign government travel document application

x Miscellaneous document requirements

x Special requirements

Once the travel document request packet is submitted to the embassy or

consular office, ICE has to follow up with the embassy or consular office every

few weeks until the travel document has been issued or the case closed.

www.oig.dhs.gov 32 OIG-19-28

F

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix F

Office of Special Reviews and Evaluations Major

Contributors to This Report

Tatyana Martell, Chief Inspector

Lorraine Eide, Team Lead

Donna Ruth, Senior Inspector

Adam Robinson, Inspector

Jason Wahl, Independent Referencer

www.oig.dhs.gov 33 OIG-19-28

G

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix G

Report Distribution

Department of Homeland Security

Secretary

Deputy Secretary

Chief of Staff

General Counsel

Executive Secretary

Director, GAO/OIG Liaison Office

Assistant Secretary for Office of Policy

Assistant Secretary for Office of Public Affairs

Assistant Secretary for Office of Legislative Affairs