Sustainable Financing of Social

Protection

Technical paper prepared for the 1

st

meeting

of the Employment Working Group under the

Indian presidency

ILO, OECD and ISSA

January 2023

2

Contents

Page

Executive summary 3

1. Introduction 4

2. Social protection coverage and financing gaps in G20 countries 6

1. Effective social protection coverage, SDG indicator 1.3.1 6

2. Financing gaps 8

3. Financing structure of social protection systems in the G20 11

4. Approaches for expanding and financing social protection among G20 members 13

1. Extending social security finance by increasing contributory revenues 13

Extension to difficult-to-cover groups 16

The role of public trust and communication 16

Strengthening contribution collection and preventing fraud 17

Optimizing the investment of social security funds and introducing ESG considerations 18

Ensuring appropriate financing forecasts and considerations for resilience 18

2. Increasing tax revenues 19

3. Eliminating illicit financial flows. 21

4. Increasing aid and transfers 22

Bibliography 24

3

Executive summary

After the Second World War, many G20 countries and invitees

1

have made significant progress in the extension

of social protection coverage, reinforced their social protection systems and established effective social

protection floors. Some have achieved universal or near-universal coverage in different branches of social

protection through a combination of non-contributory and contributory schemes and programmes. However,

other G20 countries are still lagging behind in terms of coverage, especially for essential health services. The

COVID-19 outbreak highlighted the strong need for sustainable investment in social protection including,

essential health care.

ILO estimates on the financing gap show that across the G20, the additional resources needed for achieving

universal social protection coverage range from as high as 17 per cent of GDP to as low as zero per cent in G20

countries where full coverage is observed. Countries with near zero financing gaps include those with mainly

means-tested social protection systems and those that combine earnings-related benefits with a second layer

of means-tested unemployment or social assistance programmes.

Across all countries with available data, there is a trend towards social-contribution financing. However, often,

contribution-based social protection systems also require additional general-revenue funding because (i) rights

to contributory benefits may be accumulated even when not paying into the system, e.g. pension rights

acquired during periods of unemployment or parental leave, (ii) claims may exceed contributions during

extraordinary times (e.g. unemployment schemes in times of economic crises), and (iii), contribution bases of

occupational schemes may shrink because of occupational shifts.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for extending fiscal space for social protection. ILO Recommendation No.

202 calls upon countries to consider different ways of mobilizing the necessary resources. Some G20 countries

have embraced the provisions of R202 and have recently scaled up efforts towards extending social security

finance by increasing contributory revenues. However, the declining share of labour income in total income is

posing a threat to the viability of contributory social protection systems.

To counter these trends G20 countries have extended social protection coverage for difficult-to-cover groups

such as rural, gig, and informal economy workers. Others have scaled up awareness-raising campaigns

regarding the advantages of affiliation to social protection systems. Simplifying administrative procedures,

strengthening contribution collection, and preventing fraud were also effective strategies used in the G20 to

extend the fiscal space for contributory benefits.

Taxation was another key channel used in the G20 for mobilizing resources to ensure universal social protection

coverage. However, declining corporate tax rates across all G20 countries with available data and lower

revenues from corporate taxes are posing challenges to ensure a stable stream of tax revenues to finance social

protection. To increase the availability of resources for social protection, G20 governments have used revenues

from environmental taxes, introduced voluntary tax compliance programmes for MSMEs and made dedicated

efforts to fight illicit financial flows.

1

From this point, G20 countries and invitees are referred to as G20 countries.

4

1. Introduction

In addition to claiming millions of lives, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented loss of jobs and

livelihoods and exacerbated income insecurity around the world. The impact has been particularly adverse for

people without access to social protection, including those working in the informal and care economies,

women, children, youth, and those without access to digital technologies.

More recently, fragilities in the global food and energy systems, as well as in the global economic and financial

systems, have triggered a cost-of-living crisis around the world unseen in at least a generation. This has to be

set against the backdrop of the triple planetary crises (climate change, pollution, and loss of biodiversity) and

its adverse impacts on economies and societies, including on water security and food production, health, and

well-being.

2

In the midst of these challenging circumstances, major decent work deficits persist around the world,

undermining social justice. In 2022, an estimated 214 million workers were living in extreme poverty (earning

less than US$1.90 per day per person in purchasing power parity [PPP] terms), corresponding to around 6.4

per cent of employed people.

3

More than 60 per cent of workers – some 2 billion men and women – continue

to make their living in the informal economy, mostly but not exclusively in developing countries.

4

The great

majority of these workers do not have access to social protection

5

and fundamental rights at work,

6

and, most

often, their working conditions are worsened when gender intersects with other characteristics such as, age,

disability, migration and indigenous peoples status.

7

Incomes have continued to be distributed highly unequally, such that many workers have failed to escape

poverty.

8

Evidence shows that, between 2005 and 2021, income inequality has increased in many G20 emerging

countries with a rising share of income held by the top 10 per cent and a declining share held by those at the

bottom 50 per cent of the income distribution.

9

Evidence from G20 countries shows that, more income equality

is associated with greater per capita income and that countries that have higher social protection expenditure

per capita are also those that show lower levels of inequality.

10

This means that, social protection is not only a

human right

11

and an effective instrument to enhance economic dynamism and development, but also a

powerful tool to redistribute income and reduce poverty and inequality across the lifecycle.

12

The rising levels of inequality are also compounding the challenges for central bankers in their attempt to bring

down inflation rates. With a larger proportion of aggregate consumption driven by households earning the top

10 per cent of income that are insensitive to interest rate hikes, there is a risk that a monetary policy much

tighter than in the past will be perceived as necessary in order to produce a significant impact on inflation. This

will disproportionately raise the cost for poorer households in terms of higher prices and lower employment

opportunities and also for businesses, especially MSMEs, with high levels of external financing.

13

2

IPCC 2022.

3

ILO 2023.

4

ILO 2018.

5

As of 2020, across the world 53.1 – as many as 4.1 billion people – were left fully unprotected by social protection. See also

ILO 2021c.

6

ILO 2021b; ILO 2021c; ILO 2018.

7

ILO 2023; Cattaneo, Beghini, and Pozzan 2022.

8

World Inequality Lab 2022.

9

Ibid.

10

Razavi and Cattaneo Forthcoming.

11

UN 1948.

12

Razavi and Cattaneo Forthcoming.

13

Ibid.; BIS 2022; ILO 2023.

5

In the current context of raising income inequality, economic growth is forecasted to be below 2 per cent in

2023,

14

with serious risks of tax base erosion used to finance contributory and non-contributory benefits.

Keeping existing social protection systems afloat and ensuring wider and more adequate coverage where gaps

exist will be an even greater challenge with rising debt burdens. The ILO normative framework on financing

social protection (Box 1) provides guidance regarding financing of social security and how to expand the fiscal

space for social protection.

15

This paper describes the current reach of social protection systems across G20 countries and associated

financing gaps (Section 2), as well as current funding mixes (Section 3Error! Reference source not found.). The l

ast section outlines approaches that various G20 countries adopted for expanding fiscal space for social

protection (Section 4).

Box 1. What do International Labour Standards say about financing social security?

The key international labour standards of the ILO in the field of social security are the Social Security (Minimum

Standards) Convention, 1952 (Number 102), and the Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (Number

202). While Convention 102, ratified by 63 countries (Jan. 2023), establishes minimum criteria regarding the

design and governance of social security systems, Recommendation 202 provides key principles and criteria and

envisions a two-dimensional strategy, urging countries to guarantee at least basic levels of income security and

access to essential healthcare for all (horizontal dimension), and to incrementally secure higher levels of

protection for as many persons as possible and as soon as possible (vertical dimension).

The international labour standards also provide principles and criteria for the financing of social protection

systems. Article 71 of Convention 102 establishes, in its first paragraph, that the cost of social security schemes

(including administration) shall be financed collectively by contributions and/or taxes, with due attention to

avoiding hardship for persons of small means. In its second paragraph, it sets out that the total insurance

contribution borne by workers shall not exceed 50% of the total cost of the social security scheme, while

employers (and the State when applicable) contribute at least the other half of the scheme’s cost. In the case of

employment injury schemes, the employer pays for the whole cost. In the final paragraph, the article establishes

the general responsibility of the State for the provision of the benefits, and it also requests countries to produce

actuarial reviews to ensure financial equilibrium – periodic ones and before any reform that modifies benefits

or contributions/taxes.

Recommendation 202 establishes the concept of national social protection floors, that comprise basic social

security guarantees providing basic income security as well as essential healthcare for children, persons in active

age and for older persons. In its article 12, Recommendation 202 states that national social protection floors

shall be financed by national revenues (mainly taxes and social contributions), whereas countries with lower

economic capacities can seek international cooperation and support to complement their own domestic efforts.

In article 3, the Recommendation provides the principles to be applied, including on financing (h-k): solidarity,

diversity of methods, sound management and financial, fiscal and economic sustainability. Article 11 states that

Members should mobilize funds from a diversity of sources, including a broader and more progressive revenue

base, ensure stronger compliance with tax and contribution obligations, as well as expenditure reprioritization.

Members are also advised to implement measures to prevent fraud, tax evasion and non-payment of

contributions.

14

ILO 2023.

15

Cichon, International Labour Office, and International Social Security Association 2004.

6

2. Social protection coverage and financing gaps in

G20 countries

1. Effective social protection coverage, SDG indicator 1.3.1

16

After the Second World War, many G20 countries and invitees

17

have made significant progress in the extension

of social protection coverage, reinforced their social protection systems and established effective social

protection floors. Some have achieved universal or near-universal coverage in different branches of social

protection through a combination of non-contributory and contributory schemes and programmes. For

example, this was the case in Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the Russian Federation, Spain,

the United Kingdom, and Singapore. In some G20 countries, progress in closing social protection coverage

gaps was evident between 2016 and 2020. Figure 1, which presents the proportion of the population covered

by at least one social protection cash benefit (SDG indicator 1.3.1), shows that Japan managed to increase

effective coverage by 23 percentage points in 4 years, reaching an effective social protection coverage of 98

per cent in 2020. This increase was mainly driven by an increase in social protection coverage for the

unemployed and for mothers of newborns. Similarly, Australia increased coverage for at least one social

protection cash benefit from 82 to 100 per cent between 2016 and 2020 with progress driven by the

achievement of universal coverage for old age pensions and for vulnerable persons. The latter group comprises

children, people of working age and older persons not otherwise protected by contributory schemes. Brazil,

China, India, Nigeria, Mexico, South Africa and the Republic of Korea have also increased social protection

coverage between 2016 and 2020.

Figure 1. SDG indicator 1.3.1: effective social protection coverage, 2016 and 2020 or latest available

year

Source: ILO, World Social Protection Database.

16

Proportion of population covered by at least one social protection cash benefit: ratio of the population receiving cash

benefits under at least one of the contingencies/social protection functions (contributory or non-contributory benefit) or

actively contributing to at least one social security scheme to the total population. For a full definition see:

https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/files/Metadata-01-03-01a.pdf

17

From this point, G20 countries and invitees are referred to as G20 countries.

7

Although health coverage is one of the four basic guarantees of social protection floors, as defined in

Recommendation No. 202, it is not monitored under SDG indicator 1.3.1, but under SDG indicator 3.8.1, which

corresponds to the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Index. The index captures coverage of essential health

services, defined as the average coverage of essential services.

18

The COVID‑19 crisis has revealed large gaps

in social health protection, underlining the point that ensuring universality and continuity of coverage is

essential in a context where the health of one person affects the health of everyone.

19

Developed G20 countries had already achieved very good coverage of essential services with UHC index scores

above 80 points at the onset of the pandemic. Between 2015 and 2019, many emerging G20 countries scaled

up efforts to improve their health systems, and improvements are evident in Figure 2, which presents the

evolution of the UHC index during the 4-year period. Most notably, Egypt increased the UHC index by 8 points,

followed by Indonesia (8 points), India (6 points) and Bangladesh (6 points). Progress was also evident in

China, which expanded social health protection coverage and reached UHC index score of 82 points in 2019, in

line with the UHC index population-weighted average of 83 points for high-income G20 countries in the same

year.

The COVID-19 outbreak highlighted the strong need for sustainable investment in health systems, including

the health workforce and equipment.

20

Austerity measures implemented in pre-pandemic times, which entailed

steep and indiscriminate cuts to government spending, worsened the effects of the pandemic.

21

Evidence also

showed that austerity policies had negative effects on health outcomes, especially for women living in

disadvantaged areas.

22

Figure 2. SDG indicator 3.8.1. Universal Health Coverage Index, 2015 and 2019

Note: The UHC index is reported on a unitless scale of 0 to 100, which is computed as the geometric mean of 14 tracer indicators of health

service coverage. The tracer indicators are as follows, organized by four components of service coverage: 1. Reproductive, maternal, newborn

and child health 2. Infectious diseases 3. Noncommunicable diseases 4. Service capacity and access

Source: ILO calculations based on WHO, Global Health Observatory.

18

For a full definition see: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/files/Metadata-03-08-01.pdf

19

ILO 2021c.

20

ILO 2020.

21

Arrieta 2022; ILO 2021a.

22

Walsh et al. 2022.

8

2. Financing gaps

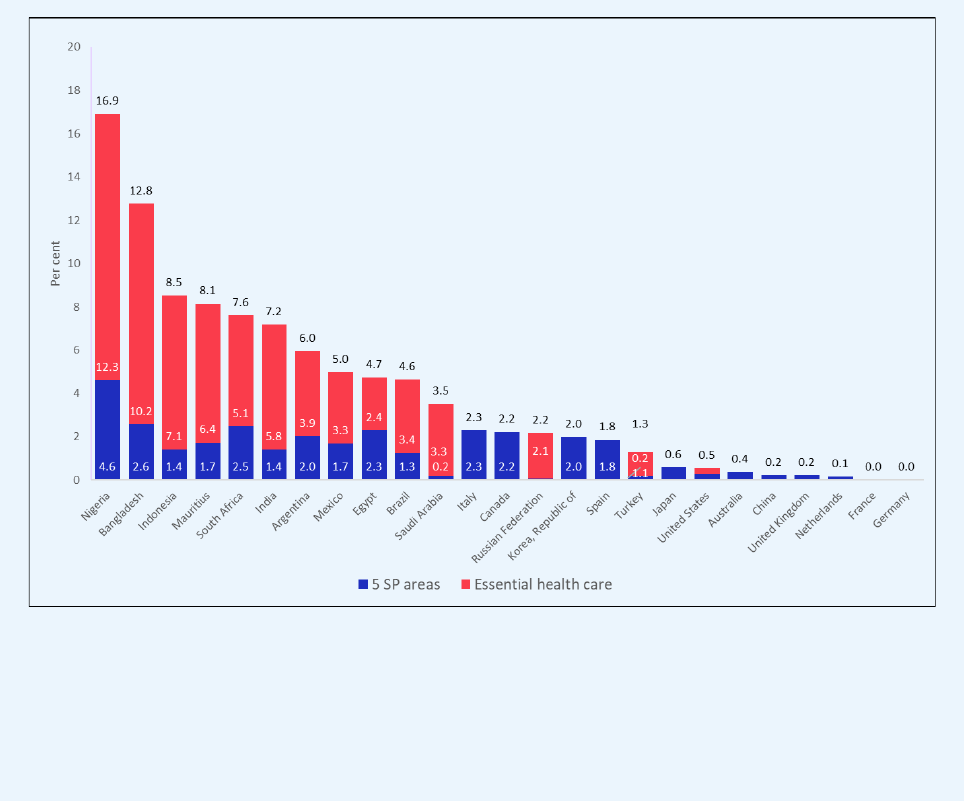

The evidence presented in the previous section showed that social protection coverage gaps persist across the

G20 and that further investment is needed to fill these gaps. In particular, prioritizing investments in nationally

defined social protection floors is vital for delivering on the promises of the 2030 Agenda. Figure 3 presents the

social protection financing gaps, measured as a percentage of GDP, for achieving universal social protection in

2022 across the G20. As expected, the financing gaps for developing countries in the G20 are significant. For

instance, in Nigeria, there is a need to invest an additional 4.6 per cent of GDP, or 23 billion USD, to achieve

universal social protection coverage for children, mothers of newborns, persons with disabilities, persons in

old-age and the unemployed. Moreover, ensuring universal coverage for essential health care services

23

would

mean progressively mobilizing an additional 12.3 per cent of GDP or 62 billion USD. A similar situation is

estimated in other emerging countries such as Bangladesh, followed by Indonesia, Mauritius and India. In

India, achievement of universal social protection including universal coverage for essential health care services,

would require spending an additional 7.2 per cent of GDP or 248 billion USD.

In developed G20 countries and China, financing gaps in essential health care are comparatively low, while

gaps for the 5 social protection areas (children, disability, maternity, old-age, unemployment) are below 3 per

cent of GDP. Figure 4 corroborates these findings by showing the proportion of total investment needed to

close the financing gaps disaggregated by each social protection area. For example, in Australia, the

Netherlands and in the United Kingdom, additional investments would need to be directed towards covering

the unemployed, while in Spain the unemployed would require 73 per cent of the total investments needed to

achieve universal social protection coverage. In China, the largest part of resources – 51 per cent or 21 billion

USD –would need to be directed towards children, in Japan 73 per cent of the funds or 18 billion USD required

to ensure universal social protection coverage would be for persons with disabilities, while in Italy 43 per cent

or 19 billion USD would be for old age persons.

The ILO Social Protection Floors Recommendation (No.202) provides a useful framework that G20 countries

may embrace to design and implement policies aimed at securing universal social protection. In particular, it

calls for using a variety of methods to mobilize the necessary resources to ensure financial, fiscal and economic

sustainability of national social protection floors, taking into account the contributory capacities of different

population groups. Such methods may include, individually or in combination, effective enforcement of tax and

contribution obligations, reprioritizing expenditure, or a broader and sufficiently progressive revenue base (see

also Box 1 and Chapter 5).

23

Universal coverage for essential health services is proxied by the achievement of Universal Health Care Index value of 84

points, which corresponds to population weighted average of the Universal Health Care Index observed across high-income

economies in the year 2022

9

Figure 3. Financing gap for achieving universal social protection coverage, as a percentage of GDP,

G20 members and invitees, 2022

Note: The estimations for the 5 social protection areas (children, disability, maternity, old-age, unemployment) consider the social protection

coverage rates of 2022 with GDP at current prices and national poverty lines for the year 2022. The estimation for essential health care is

produced in two steps. 1) The elasticity of the Universal Health Coverage Index (SDG indicator 3.8.1) to health expenditure as percentage of

GDP is estimated in a panel regression covering 194 countries for the years 2000 to 2022. 2) The estimated elasticity is used to calculate in each

country the additional percentage points of GDP that needs to be allocated to health expenditure to reach a Universal Health Care Index value

of 84 points, which corresponds to population weighted average of the Universal Health Care Index observed across high-income economies

in the year 2022. Estimations for Oman, United Arab Emirates and Singapore are not available as no national poverty line was found.

Source: ILO estimates based on ILO forthcoming, Financing gaps in social protection 2023 revision.

10

Figure 4. Distribution of the financing gap for achieving universal social protection coverage across

the G20 members and invitees, 2022

Note: Estimates for Oman, United Arab Emirates and Singapore are not available as no national poverty line was found.

Source: ILO estimates based on ILO forthcoming, Financing gaps in social protection 2023 revision.

Differences in public social spending explain some, but not all, of this cross-country variation in social protection

coverage and financing gaps. Among countries with available data, the Republic of Korea does have the lowest

level of aggregate social spending, and France the highest (Error! Reference source not found.5). But the c

omposition of public social spending on health, working-age benefits and old-age pensions matters as well,

especially since health services and some old-age pensions are privately provided in some countries. For

instance, public social spending is somewhat higher in the United States than in Australia, where more jobless

low-income individuals receive support. This is because public social expenditure in the United States is mostly

made-up of old-age pensions and health services, whereas most old-age pensions in Australia are private, and

public social expenditure in Australia thus skews more towards working-age support. Public social expenditure

in Italy is also higher than in Germany, where social protection financing gaps are zero (Figure 3). As a

percentage of GDP, Italy also spends more on working-age support than Germany, however benefits in

Germany are more targeted to low-income households.

24

The gap in coverage rates between standard and non-standard workers are the largest where (i) benefits are

mainly contribution-based, (ii) non-standard workers are not covered at all or only partially covered, and (iii)

social assistance programmes either do not exist or are inaccessible (e.g. Italy and Korea). Countries with low

or no access gaps include those with mainly means-tested social protection systems (Australia, the United

Kingdom and the United States), and those that combine earnings-related benefits with a second layer of

means-tested unemployment or social assistance programmes (e.g. France and Germany).

25

24

Immervoll, Hyee, et al. 2022; OECD 2022.

25

OECD Forthcoming.

11

3. Financing structure of social protection systems in

the G20

Financing strategies and policy setups differ significantly across countries. Some countries rely mainly on

general revenue to grant basic health-services to all residents and means-tested benefits for working-age

support, and have a high share of private expenditure for old-age pensions (e.g. Australia, Canada, the United

Kingdom and, to a lesser degree, the United States). In other countries, workers acquire entitlements to

earnings-related benefits such as unemployment insurance, disability and parental-leave benefits as well as

old-age pensions through contributions, with a limited role for general-revenue-financed, means-tested

transfers for those who do not have the required contribution history, but operate a general-revenue financed

healthcare system (e.g. Italy, the Republic of Korea or Spain). A third group combines a contribution-funded

health-care system and insurance-based out-of-work benefits (including old-age pensions) with means-tested

benefits for low-income households, and universal benefits for children (e.g. France and Germany, see Error! R

eference source not found.5).

The funding mix can differ across countries that have similar levels of spending, reflecting different policy

institutions (such as privately or publicly-funded healthcare and pension systems), but also different strategies

for balancing the various objectives of social protection – such as risk sharing, income smoothing over time,

inequality reduction and poverty alleviation. Often, contribution-based social protection systems also require

additional general-revenue funding because (i) rights to contributory benefits may be accumulated even when

not paying into the system, e.g. pension rights acquired during periods of unemployment or parental leave, (ii)

claims may exceed contributions during extraordinary times (e.g. unemployment schemes in times of economic

crises), and (iii), contribution bases of occupational schemes may shrink because of occupational shifts – e.g.

the miners’ pension scheme in Germany.

Figure 5. Public social spending by social security contributions and general revenue funding, in % of

GDP, 2019

Note: Social expenditure includes (public) old age and survivor pensions, income support to the working age population, (public) health

spending, as well as other social services. The share of general revenue financing is calculated as an residual by subtracting social insurance

contributions from overall social spending. It therefore includes all other sources of social financing other than social insurance

contributions. While these are mostly general tax revenue, some countries (e.g. Tobacco taxes in France) operate taxes earmarked for social

spending. * Australia (2017), Canada (2018). The EU average excludes Bulgaria, Croatia, the Republic of Cyprus, Malta and Romania. In-kind

healthcare and some old-age pensions are private in the Netherlands (in 2019, private social expenditure accounted for 13% of GDP).

Source: OECD SOCX database (social expenditure), OECD Tax database (social insurance contributions)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

MEX TUR KOR NLD AUS CAN USA OECD GBR JPN EU ESP DEU ITA FRA

Social insurance contributions General revenue

12

Figure 6. Development of public social spending by social security contributions and general revenue

funding, in % of GDP

Note: Social expenditure includes (public) old age and survivor pensions, income support to the working age population, (public) health

spending, as well as other social services. The share of general revenue financing is calculated as a residual by subtracting social insurance

contributions from overall social spending. It therefore includes all other sources of social financing other than social insurance

contributions. While these are mostly general tax revenue, some countries (e.g. Tobacco taxes in France) operate taxes earmarked for social

spending. The EU average excludes Bulgaria, Croatia, the Republic of Cyprus, Malta and Romania; in 2000 and 1980 additionally the Czech

Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: OECD SOCX database (social expenditure), OECD Tax database (social insurance contributions)

Most G20 countries with mature social protection systems expanded social spending over the last four decades,

with particularly strong increases in Japan, Italy and France (+ eleven to twelve percentage points of GDP).

Japan mainly increased spending on health services, and to a lesser degree old-age pensions, and Italy and

France mainly on old-age pensions and working-age cash benefits. Also, Turkey increased spending by nine

percentage points, mainly on old-age pensions and healthcare. The Netherlands are an outlier in that public

social expenditure declined since 1980, mainly because of a reform that privatised healthcare provision in

2006.

26

Across all countries with available data, there is a trend towards social-contribution financing. Thus, an

increasing share of total social protection spending is paid exclusively by workers and employers. Turkey

almost reversed its funding mix from two-thirds general revenue, one-third social contribution-funded to two-

thirds contribution funded. Japan, Spain and Germany also increasingly rely on social contributions to fund

rising social expenditure. France, and to a lesser extent Italy, are the only countries with available data that

increased the share of general revenue (Figure 6. Development of public social spending by social security

contributions and general revenue funding, in % of GDP

26

Immervoll, Fernandez, et al. 2022.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1980

2000

2010

Social insurance contributions

General revenue

13

Note: Social expenditure includes (public) old age and survivor pensions, income support to the working age population, (public) health

spending, as well as other social services. The share of general revenue financing is calculated as a residual by subtracting social insurance

contributions from overall social spending. It therefore includes all other sources of social financing other than social insurance

contributions. While these are mostly general tax revenue, some countries (e.g. Tobacco taxes in France) operate taxes earmarked for social

spending. The EU average excludes Bulgaria, Croatia, the Republic of Cyprus, Malta and Romania; in 2000 and 1980 additionally the Czech

Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: OECD SOCX database (social expenditure), OECD Tax database (social insurance contributions)

6).

4. Approaches for expanding and financing social

protection among G20 members

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for extending fiscal space for social protection. ILO Recommendation No.

202 calls upon countries to consider different ways of mobilizing the necessary resources (Box 1). G20 countries

where large coverage and financing gaps persist need to invest more and better in social protection, on the

basis of principles of universality, adequacy, sustainability and solidarity. Not only the design and

implementation of social protection systems, including floors, but also decisions on their financing need to be

adapted to the developments in the world of work and guided by effective social dialogue. G20 experiences

show that countries usually adopt different strategies for creating fiscal space.

27

Some of the emerging

strategies used across the G20 are discussed below.

1. Extending social security finance by increasing contributory

revenues

Social security contributions play a critical role in financing social protection. Social security contributions are

linked to legal entitlements and should be considered a deferred wage and a social and economic investment.

27

ILO 2019a; ILO 2019b; ILO 2021c.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1980

2000

2010

Social insurance contributions

General revenue

14

According to the ILO Convention C102, social security contributions shall be collected in a manner which avoids

hardship to persons of small means and takes into account the economic situation of the member and the

classes of persons protected. Furthermore, the total of the insurance contributions borne by the employees

protected shall not exceed 50 per cent of the total of the financial resources allocated to the protection of

employees and their families including children.

28

Social security contributions have represented a reliable way to finance social protection in many G20 countries,

with the highest share of total government revenues represented by social security contributions at 40.4 per

cent in Japan (Figure 7).

29

In most G20 countries where the initial design of social protection systems was made

under strong Bismarckian influence linked to social insurance and even in those countries that have moved

towards the Beveridge universalist model, social security contributions continue to be predominant, regardless

of their level of national income.

30

In some G20 countries, social contributions are low or virtually non-existent, but not always for the same

reasons. Canada, the United Kingdom and Singapore have mature social security systems that are mostly tax-

financed. In G20 emerging countries, social security systems are still in need of substantial investments to reach

universal coverage, which explains the low proportion of social contributions.

Figure 7. Share of social security contributions as a percentage of total government revenues, 2005-

2020, per cent

Source: OECD, Global Revenue Statistics. Insert source here

The amount of income that is produced by labour, which includes wages and work-related earnings of the self-

employed, is strongly linked with the country’s capacity to generate revenues from social security contributions.

In developed countries, the share of income attributable to labour clustered around 60 per cent in 2019, while

in the G20 emerging countries, it remained mostly below 50 per cent (Figure 8). Between 2004 and 2019, the

share of labour income in total income has mostly stagnated and, in some instances decreased, also in the

advanced G20 countries. These trends are probably exacerbated by the decline of real wages in the first half of

2022, which is estimated at –2.2 per cent in the advanced G20 economies.

31

28

ILO 2019a.

29

The share of total government revenues represented by social security contributions is missing in India, Oman, Russian

Federation, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

30

ILO 2019a.

31

ILO 2022c.

15

In the emerging G20 countries, the labour income shares mostly increased. In China, for example, the labour

income share increased from 50 per cent in 2004 to 52 per cent in 2019. These trends seem to be sustained by

modest, though positive, wage growth of 0.8 per cent observed in G20 emerging economies in the first half of

2022.

32

There are exceptions, however, one being Mexico, where the labour income share decreased and

where, together with Italy, Japan and the United Kingdom, real wages were lower in 2022 than in 2008.

33

There are several possible explanations for this trend, including the impact of technological changes, increased

globalization, the enhanced exercise of market power by large firms in concentrated product markets, the

decline in unionization rates and the erosion of the bargaining power of workers in labour markets.

34

Figure 8. Share of labour income in total income, 2004-2019

Source: ILOSTAT, 2023.

In this context of declining wages and labour income shares in advanced economies, as well as widespread

income inequality and persistent labour market informality in emerging G20 countries, many G20 countries

have taken steps to broaden the contribution base and improve collection mechanisms. Example of emerging

practices observed across the G20 include the following:

32

Ibid.

33

Ibid.

34

Karabarbounis and Neiman 2014; Grossman and Oberfield 2022.

16

Extension to difficult-to-cover groups

Contributory social security systems have been extended to the so-called difficult-to-cover groups, which

include very different categories of workers ranging from domestic workers and rural workers to the low-

income self-employed - also known as the “missing-middle” – as well as platform workers. Workers pertaining

to these groups have often one common characteristic: they are working in the informal economy.

Building on the concrete experience of ILO member countries, the ILO Transition from the Informal to the

Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204) provides a useful framework to ensure that an integrated

policy framework to facilitate the transition to the formal economy is included at all levels of government with

a view to progressively extending coverage of social protection for all, including for difficult-to-cover groups in

the informal economy. According to R204, reducing compliance costs by introducing simplified tax and

contributions assessment and payment regimes is one concrete way of moving in this direction.

Several G20 countries have adopted strategies in line with this provision, by for example, simplifying

administrative procedures to enable difficult-to-cover workers to enrol and pay contributions together with

other formalities, such as tax payments through single portals and mobile apps. Argentina,

35

Brazil

36

and other

Latin American countries as well as Indonesia

37

and other Asian countries have implemented schemes and

service delivery tools to cover these groups. In addition, very low-income self-employed can benefit from

government subsidies to their contributions, for instance, in the Monotributo/Monotax schemes in Argentina

and Brazil.

38

Some countries are also applying these approaches to cover platform workers, which is discussed

in a separate paper presented to the EWG.

Despite the challenges and costs, developing effective mechanisms for collecting contributions is crucial to

ensure broad and effective coverage for all types of workers. Countries such as Argentina, France, Indonesia

and Spain leveraged their capacity generated by implementing regular contribution collection systems to

develop systems tailored to difficult-to-cover groups. Extending coverage and workers’ formalization through

contributory schemes are crucial for improving social protection financing and sustainability. Although this may

involve short-term investments and eventual subsidies, it ensures the comprehensive enrolment of, and

contribution collection from, large numbers of workers that can increase social security revenues in the middle

and long term. In addition, these measures also help improve public trust in the social security system as well

as support for expenditures, especially among younger generations, who are increasingly working in new types

of jobs.

39

The role of public trust and communication

The readiness of individuals and of society as a whole to pay for social security systems impacts significantly on

their financing. But it is sometimes overlooked. The acceptance to contribute and support political decisions in

this regard is linked to public trust in the capacity of the system to deliver reliable and quality benefits. Efforts

to communicate appropriately about social security, reform initiatives and high-quality service delivery are

important strategies in this regard. An example is the question of educating younger generations on the vital

role and delivery capacity of old-age pension systems. To counter disinformation and strengthen trust in the

pension system among the younger population, Japan

40

introduced on-site pension lessons in schools and

developed study tools including “pension manga”. The French social security institutions implemented

35

ISSA 2017.

36

ILO 2019c.

37

ISSA 2020b.

38

ISSA 2021h.

39

ISSA 2022d.

40

ISSA 2021g.

17

communication campaigns strengthening the visibility of the positive impact of social security and its key role

for citizens’ daily life as well as enhancing public support for social security.

41

In Oman, the social security

institution has collaborated with academic and educational institutions to educate students and children about

social security and its importance.

42

Strengthening contribution collection and preventing fraud

Independently from the categories of workers and employers, improving contribution collection and

compliance enforcement mechanisms is key to maximizing social security financing through contributions. To

enhance compliance, recent practices have demonstrated the importance of making the dealings with social

security administration as simple and tailored as possible.

43

Spain has implemented a tailored portal to facilitate

domestic workers' registration and contribution payment. The portal aims to overcome barriers related to

administrative, communication and web design complexities.

44

France has also developed a tailored portal for

the self-employed and entrepreneurs to facilitate registration and contribution payment.

45

These experiences

also show that in addition to developing the institutional capacities of administrations to implement these

tailored approaches, attention must also be paid to developing the understanding and capacities of

contributors, especially among the low-income self-employed and difficult to cover groups. More recently, the

application of behavioural insights techniques has also enabled influencing the behaviour of contributors and

strengthen compliance.

46

For instance, by applying these innovative behavioural techniques, Indonesia could

reduce social security contributions arrears of employers and encourage them to make on-time payments of

member contributions. They tested the effectiveness of different email interventions to influence employers to

increase contribution payments before the monthly deadline.

47

Appropriate measures to prevent and detect fraud in social security contributions are fundamental for

contributory social security systems due to the financing implications and the potential impact on reputation

and public trust. Many G20 countries have implemented innovative mechanisms addressing the ever-evolving

challenges in this area. Notably, Argentina, France, Indonesia, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Spain have

developed fraud detection systems using data analysis, predictive analytics, and data exchange with other

public agencies.

48

In addition, Mexico and Singapore developed fraud prevention measures fostering

voluntary compliance by applying behavioural insights techniques. Concretely, the Mexican IMSS provided the

employees monthly reports on the contributions made by the employers as a dissuasive and corrective

measure to address under-declaration.

49

In turn, the Singapore CPFB fostered self-employed enrolment and

voluntary compliance by simplifying the enrolment and contribution payment, developing communication

campaigns and providing a government contribution during a transitionary period.

50

Previously, as part of the

WorkRight initiative, the CPFB developed video spots and advertising posters to educate employers on their

legal obligations and employees on their rights.

51

41

ISSA 2022a.

42

ISSA 2021c.

43

ISSA 2019.

44

ISSA 2022c.

45

ISSA 2022b.

46

ISSA 2021b.

47

Ibid.; The Behavioural Insights Team 2019.

48

ISSA 2018a; ISSA 2018b; ISSA 2020a; ISSA 2021a; ISSA 2022a; García Huete 2022.

49

ISSA 2023.

50

ISSA 2021d.

51

WorkRight initiative (Singapore): https://youtu.be/QZ8E8cUQEkg

18

Optimizing the investment of social security funds and introducing ESG

considerations

A number of G20 countries, including the Republic of Korea, Japan, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and the United

States have established public social security reserve funds to secure the capacity to pay benefits during times

when current expenditures exceed current contribution income. The biggest social security reserve funds have

been established in the area of old-age protection and retirement schemes and they are usually managed by a

social security institution under regulations and oversight by other government bodies.

These social security funds not only play a key role in the future financing of benefits but also allow for

anticyclical measures in case of unexpected events and crises. It is in the interest of covered population and all

stakeholders that social security funds are invested with an appropriate asset/liability management,

appropriate investment horizons and an optimal risk/return ratio. In addition, sound governance must be in

place to ensure that investment decisions are made in the best interests of scheme members and without

undue influence.

Efforts to strengthen investment approaches have been undertaken in order to enhance the funding ratio of

schemes and of the broader social security systems. Indonesia’s social security institution has worked towards

strengthening asset-liability management and to achieve more dynamic investment management with regard

to improving the funding ratio of old-age pensions.

52

In Oman, the social security institution has enhanced data

management and investment risk assessment and thereby contributed to strengthening of the funding ratio.

53

An important development has been the inclusion of a mandate for environmental, social and governance (ESG)

investment in the portfolio decisions of public social security reserve funds. ESG investment is also linked to a

growing attention to infrastructure investment designed to enhance domestic growth opportunities that are

expected to also support the future financing of social protection systems. The National Pension Service of

Korea carries out ESG evaluation for specific asset classes.

54

The Government Pension Investment Fund of

Japan adopted an ESG index for domestic equities focussing on the measures taken by companies related to

emissions and climate change.

55

The unemployment insurance scheme in France has introduced social impact

considerations in their debt financing strategies through social bonds.

Ensuring appropriate financing forecasts and considerations for resilience

Regular and high-quality financial forecasts are essential for the formulation of long-term financing strategies

for social protection schemes. Actuarial valuations are at the core of these and are indispensable to assess the

sustainability of social security programmes but are also required to assess system adequacy, financing and

funding considerations. Actuarial valuations and financial forecasts are based on a range of assumptions

including life expectancy, labour market participation, scheme coverage, real wage increases or economic

growth, and are inherently complex. Findings of actuarial valuations also have an impact on investment

decisions, benefit calculations and communication. The approach to assessing the financial obligations of social

security systems should also be consistent across systems and with other public spending and not encourage

or promote a particular financing approach.

In this regard, efforts must continue to ensure that decisions regarding the financing of social protection are

based on the best available evidence and assumptions. The ILO has recently developed new actuarial models

for social security pensions and health that are accessible via the ILO/ISSA actuarial services platform launched

this year.

Climate related risks, shocks to livelihoods and extreme events make financial forecasting even more complex

but also require the increasing consideration of the financial means necessary for ensuring both the resilience

of social protection systems and the contribution that social protection makes to societal and economic

52

ISSA 2021e.

53

ISSA 2021f.

54

NPS 2023.

55

Government Pension Investment Fund 2023.

19

resilience. The recent pandemic demonstrated this need as an erosion of revenue sources from both

contributions and investments met an unprecedented increase in the need for benefit expenditures. To

enhance the capacity for anticyclical financing in social protection and prepare for extreme events, risk

management methodologies need further attention.

2. Increasing tax revenues

Taxation is the other key channel for mobilizing the resources that governments need to establish universal

social protection systems, including floors, that provide adequate protection for all in need across the life cycle.

Countries have a wide range of options to raise tax revenues, the most common are consumption/sales and

value added tax (VAT), progressive taxation such as income, wealth and corporate taxes –including taxes on the

financial sector– as well as property, inheritance and environmental taxes (Box 3).

International competition for inward FDI has led many G20 governments to reduce tax rates and to otherwise

increase tax concessions to corporations. Figure 9 shows that, without exception, all 13 G20 countries with

available data have reduced their corporate tax rates over the past 20 years. However, there is no consensus

on the advantages of granting such concessions in the matter of direct taxes, since the diversion of

international investment or the attraction of such flows is determined by many factors, including the quality

and availability of infrastructure, human capital, and institutions. Therefore, G20 countries should examine the

cost and benefits of such tax concessions as they may constitute an unnecessary loss of revenue, which could

be used to ensure universal social protection coverage.

56

Declining corporate tax rates mirrors lower

proceedings from corporate taxes as a share of GDP. In 8 out of 13 G20 countries with available data,

government revenues from corporate taxes have declined, driven by lower tax rates, but also by non-

compliance with tax obligations (Figure 10).

Governments face challenges in ensuring compliance with taxes at all levels from wage and salaried workers,

own-account workers, MSMEs to large corporations. To promote tax compliance for small contributors,

voluntary tax compliance programmes have been adopted across the G20 (e.g. Argentina, Indonesia, Spain).

Countries may introduce these programmes for a variety of reasons including, among others, raising tax

revenue, regularising the payment of social security contributions, and/or facilitating asset repatriation for the

purpose of economic policies, especially when the country is in an economic crisis.

57

Increasing tax compliance and/or raising tax rates are important strategies to expand fiscal space for social

protection. Equity, gender balance, efficiency, and administrative feasibility are other key criteria that must be

factored in when designing and evaluating tax systems. Countries face significant problems in tax policy due

to globalization and other factors, such as illicit financial flows. Global and regional tax cooperation is needed

to deal with these problems effectively.

56

ILO 2019a.

57

Council of Europe 2014.

20

Box 3. The emerging role of environmental taxes for financing social protection

In the context of the green transition, the main purpose of environmental taxes (carbon taxes, excise taxes on

fuels, and revenues from emissions trading systems) is to disincentivise carbon emissions. But they can form

part of a sustainable financing strategy for social protection through revenue recycling.

58

OECD research shows that in 2019, 60% of 40 countries studied earmark at least part of the revenue from

environmental taxation. Of the 19 G20 countries with available data

59

, only the United Kingdom earmarks a

small share of the revenue generated from excise taxes on fuels for tax policy changes (such as tax rebates).

However, South Africa uses revenue from excise taxes to fund an insurance scheme for victims of road injuries,

and Argentina dedicates part of the revenue to the social security administration and the national housing fund.

Only Australia, Canada, France, Mexico and the United Kingdom operated carbon taxes in 2019, but Australia,

Canada and France earmarked at least half of the revenue to tax policy changes, indicating that carbon taxes

are seen as part of broader tax reform efforts. Revenues from emissions trading systems are mostly earmarked

for spending on renewable energy and transport, with no G20 country explicitly earmarking any of the

revenues for taxes or social spending in 2019.

The potential for carbon tax revenue is certainly substantial. OECD estimates show that (abstracting from

behavioural responses), increasing the price of carbon emissions to EUR 30 per tonne of CO

2

emissions (a

conservative estimate of the social cost of carbon emissions) would generate additional revenues of about 5%

of GDP in India, about 1% in Brazil, the United States, Canada, Australia, Argentina, Mexico, Turkey, and of

about 0.5-1% in Japan, Spain, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands

and Italy.

Figure 9. Corporate tax rates, 2000-2022

Source: OECD Tax Statistics.

58

Immervoll and Kerschbaumer 2022.

59

Excluding Indonesia, the Russian Federation and Saudi Arabia, but including visiting countries the Netherlands and Spain.

21

Figure 10. Corporate tax revenues as a percentage of GDP, 2000-2022

Source: OECD Tax Statistics.

3. Eliminating illicit financial flows.

Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) generally involve money laundering, bribery by international companies, tax evasion

and trade mispricing. Stemming IFFs and fighting corruption can be a significant source of fiscal space for socio-

economic development.

Domestic tax base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) due to multinational enterprises exploiting gaps and

mismatches between different countries' tax systems affects all G20 countries. Developing countries' higher

reliance on corporate income tax means they suffer from BEPS disproportionately. Working together in the

OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, over 135 countries and jurisdictions are implementing 15 Actions to

tackle tax avoidance, improve the coherence of international tax rules, ensure a more transparent tax

environment and address the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy.

60

Efforts should be

continued during the Indian presidency to ensure that more government finance is available for closing the

coverage and financing gaps in social protection.

Success in this would alone free up more than ten times the annual total of official development assistance

(ODA) disbursed and received across the globe. Such is the extent of resources that illegally escapes developing

countries every year.

61

There are increased efforts to crack down on money laundering, bribery, tax evasion,

trade mispricing and other financial crimes that are not only illegal but also reduce much-needed revenues for

social protection and work towards the SDGs. For Egypt, it is estimated that combating illicit financial outflows

could on average generate an annual amount equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP; illicit financial outflows from the

country in 2014 were estimated at between 1.9 per cent and 4.7 per cent of GDP.

62

Egypt is one of the few

countries where data are available. To improve measurement of illicit financial and arms flows, UNCTAD is

piloting a project in 8 developing countries, including Nigeria.

60

OECD 2023a.

61

ILO 2019a.

62

Ibid.

22

4. Increasing aid and transfers

Official development assistance (ODA) is defined as government aid that promotes and specifically targets the

economic development and welfare of developing countries. Despite calls for enhanced ODA to support

financing for sustainable development,

63

and agreement on a target commitment of 0.7 per cent of gross

national income (GNI), ODA in fact represented only 0.33 per cent of the combined GNI of the member countries

of the Development Assistance Committee in 2021.

64

Among G20 donor countries, only Germany met the 0.7

target (Figure 11). Not only did donor countries fall short of their commitments; the share of their actual

disbursements of ODA allocated to social protection in 2017 represented a mere 0.0047 per cent of their GNI.

65

To avoid that the “great divergence” between richer and poorer economies continues to characterize the labour

market recovery in 2022,

66

in September 2021, during the General Assembly, jointly with the ILO the United

Nations Secretary General launched the Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for a Just

Transition. This initiative aims to increase the level and coordination of the multilateral system’s efforts to help

countries create 400 million decent jobs, including in the green, digital and care economies, to extend social

protection coverage to the 4 billion people currently excluded and facilitate just transitions, efforts which are

vital to poverty reduction and achieving the SDGs as a whole.

67

The Accelerator includes three complementary

and mutually supportive pillars:

• Pillar 1 addresses policy dimensions, in particular by developing integrated national employment,

social protection and just transition strategies.

• Pillar 2 addresses the challenge of resource mobilisation, complementing domestic fiscal efforts with

international financial support, including from international financial institutions and public

development banks.

• Pillar 3 aims to enhance multilateral cooperation to build political momentum and strategic support

for the Accelerator.

A transversal, system-wide Technical Support Facility (TSF) will advise on the work under the three pillars

and seek to align financial and technical assistance for a human-centred recovery and sustainable development.

Another option for complementing pillar 2 on financing is the Global Fund for Social Protection launched by

the Global Coalition for Social Protection Floors, the UN Rapporteur on Extreme poverty and Human Rights and

the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) and endorsed by the tripartite constituents at the

International Labour Conference in 2021.

68

The Global Fund for Social Protection could be integrated in the

Global Accelerator and it could aim to support countries to design, implement and, in specific cases, to finance

national floors of social protection.

63

United Nations 2015.

64

OECD 2023b.

65

ILO 2021c.

66

ILO 2022b.

67

ILO 2022a.

68

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_806099.pdf

23

Figure 11. Official Development Assistance as a percentage of Gross National Income, 2021

Source: OECD 2023b.

24

Bibliography

● Arrieta, Tania. 2022. Austerity in the United Kingdom and its legacy: Lessons from the COVID-19

pandemic. Available at <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/10353046221083051>.

Accessed 22 January 2023.

● BIS. 2022. Inequality hysteresis and the effectiveness of macroeconomic.

● Cattaneo, Umberto, Valentina Beghini, and Emanuela Pozzan. 2022. The Urgency of a Quantum Leap for

Gender Equality in the World of Work.

● Cichon, Michael, International Labour Office, and International Social Security Association, eds. 2004.

Financing social protection. Quantitative methods in social protection series. Geneva: ILO.

● Council of Europe. 2014. Procedures related to the implementation of voluntary tax compliance programmes

and AML/CFT requirements by countries and territories evaluated by MONEYVAL.

● García Huete, Jacinto. 2022. Big Data & Analytics at the General Treasury of Social Security (TGSS). Tallinn.

Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/node/226687>.

● Government Pension Investment Fund. 2023. GPIF Adopted a ESG Index for Japanese Equities. Available at

<https://www.gpif.go.jp/en/investment/esg>.

● Grossman, Gene M., and Ezra Oberfield. 2022. The Elusive Explanation for the Declining Labor Share.

Annual Review of Economics 14 (1): 93–124.

● ILO. 2018. Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture. Third edition. Report. Geneva: ILO.

Available at <http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_626831/lang--en/index.htm>.

Accessed 15 May 2018.

● ILO. 2019a. Fiscal space for social protection. A hanbook for assessing financing options. Available at

<https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---

soc_sec/documents/publication/wcms_727261.pdf>. Accessed 17 January 2023.

● ILO. 2019b. ILO Centenary Declaration for the Future of Work. Available at

<https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---

relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_711674.pdf>. Accessed 17 January 2023.

● ILO. 2019c. Simples National: Monotax Regime for Own Account Workers, Micro and Small Entrepreneurs

Experiences from Brazil.

● ILO. 2020. ILO Sectoral Brief: COVID-19 and the health sector. Available at

<https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---

sector/documents/briefingnote/wcms_741655.pdf>. Accessed 22 January 2023.

● ILO. 2021a. Assessment of the Social Security Responses to COVID-19 Lessons from the Western Balkans and

Eastern Europe during the first stage of the pandemic. Available at

<https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---europe/---ro-geneva/---sro-

budapest/documents/publication/wcms_775160.pdf>. Accessed 22 January 2023.

● ILO. 2021b. Extending social security to workers in the informal economy. Lessons from international

experience. Available at <https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/RessourcePDF.action?id=55728>.

Accessed 20 January 2023.

● ILO. 2021c. World Social Protection Report 2020–22: Social Protection at the Crossroads – in Pursuit of a Better

Future. Geneva.

● ILO. 2022a. Concept note on the Global Accelerator on Jobs and Social Protection for Just Transition.

● ILO. 2022b. ILO Monitor on the world of work. Ninth edition. Available at

<https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---

publ/documents/briefingnote/wcms_845642.pdf>. Accessed 23 January 2023.

25

● ILO. 2022c. Global wage report 2022-23 : the impact of inflation and COVID-19 on wages and purchasing

power. 1st ed. ILO. Available at

<https://labordoc.ilo.org/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma995215392702676&context=L&vid=41ILO_IN

ST:41ILO_V2&lang=en&search_scope=ALL_ILO&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=ALL_ILO&qu

ery=any,contains,global%20wage%20report%202022&offset=0>. Accessed 20 January 2023.

● ILO. 2023. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023. Geneva. Available at

<https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---

inst/documents/publication/wcms_865332.pdf>. Accessed 17 January 2023.

● Immervoll, H, and F Kerschbaumer. 2022. Financing social protection in OECD countries: An issue paper.

● Immervoll, Herwig, Rodrigo Fernandez, Raphaela Hyee, Jongmi Lee, and Daniele Pacifico. 2022. De-facto

gaps in social protection for standard and non-standard workers: An approach for monitoring the accessibility

and levels of income support. Paris: OECD. Available at <https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-

migration-health/de-facto-gaps-in-social-protection-for-standard-and-non-standard-

workers_48e282e7-en>. Accessed 23 January 2023.

● Immervoll, Herwig, Raphaela Hyee, Rodrigo Fernandez, and Jongmi Lee. 2022. How Reliable are Social

Safety Nets? Value and Accessibility in Situations of Acute Economic Need. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Available at <https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=4114808>. Accessed 23 January 2023.

● IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022 Mitigation of Climate Change.

● ISSA. 2017. Single portal for monotax contributors (monotributistas). Practice of the Federal Administration of

Public Resources - Argentina. Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/162516>.

● ISSA. 2018a. Data integration between the PASI and related government agencies: Enabling the electronic

registration of employers and insured persons . Practice of the Public Authority for Social Insurance – Oman.

Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/173444 .>.

● ISSA. 2018b. Smart Inspection System. Practice of the Public Authority for Social Insurance – Oman. Available

at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/173444 .>.

● ISSA. 2019. ISSA Guidelines on Error, Evasion and Fraud in Social Security Systems.

● ISSA. 2020a. Addressing error, evasion and fraud through Analytics. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/webinar-2020-09-08 .>.

● ISSA. 2020b. Auto-debit without a bank account to collect contributions - Increasing collections from informal

sector members. Practice of BPJS Kesehatan - Indonesia. Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/212216>.

● ISSA. 2021a. Addressing error, evasion and fraud in social security: Good practices from the Americas.

Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/analysis/Addressing-error-evasion-and-fraud-in-social-security-Good-

practices-from-the-Americas>.

● ISSA. 2021b. Behavioural insights and social security. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/analysis/behavioural-insights-and-social-security>.

● ISSA. 2021c. Enrich students’ knowledge on social protection: A cooperative programme with academic and

educational institutions in Oman. A practice of the Public Authority for Social Insurance. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/gp/211724>.

● ISSA. 2021d. Framework on behavioural insights. Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/events/webinar-2021-

11-12>.

● ISSA. 2021e. Old-age programme with asset liability management approach. A practice of the National Social

Security Administering Body for Employment. Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/212383>.

● ISSA. 2021f. PASI investment portfolio: Risk and return analysis. A practice of the Public Authority for Social

Insurance. Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/211717>.

● ISSA. 2021g. Pension communication tools targeting the younger generation: On-site pension lessons at

school, Pension Manga and Pension Quiz Video. A practice of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of

Japan. Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/212385>.

26

● ISSA. 2021h. The ISSA’s Behavioural Insights Framework: A recommended approach. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/node/217895>.

● ISSA. 2022a. A common approach to communication to highlight the engagement of the French social security

system during the crisis and to ensure a better image in the long term. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/gp/218123>.

● ISSA. 2022b. Auto-entrepreneur: an ultra-streamlined, 100 per cent digital system for registering, managing

and declaring one’s activities in a few clicks. A practice of the Central Agency of Social Security Bodies – France.

Available at <https://ww1.issa.int/gp/217405 .>.

● ISSA. 2022c. Importass: The new portal of Spain’s General Treasury of Social Security. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/gp/218711 .>.

● ISSA. 2022d. ISSA Guidelines on Administrative Solutions for Coverage Extension.

● ISSA. 2023. The ISSA Behavioural Insights Framework and applications to improve compliance. Available at

<https://ww1.issa.int/events/webinar-2023-01-18>.

● Karabarbounis, Loukas, and Brent Neiman. 2014. The Global Decline of the Labor Share. The Quarterly

Journal of Economics 129 (1): 61–103.

● NPS. 2023. Responsible investment. Available at

<https://fund.nps.or.kr/jsppage/fund/mcs_e/mcs_e_06_03.jsp>.

● OECD. 2022. Social Expenditure Database (SOCX) - OECD. Available at

<https://www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm>. Accessed 23 January 2023.

● OECD. 2023a. Base erosion and profit shifting - OECD BEPS. Available at

<https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/>. Accessed 23 January 2023.

● OECD. 2023b. Official development assistance (ODA) - OECD. Available at

<https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-

standards/official-development-assistance.htm>. Accessed 17 January 2023.

● OECD. Forthcoming. Income security during joblessness in the United States: Design of effective

unemployment support.

● Okun, Arthur M., ed. 1975. Exploring ‘The Big Tradeoff’. The Brookings Bulletin 12 (3). Brookings Institution

Press: 10–15.

● Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

● Razavi, Shahrashoub, and Umberto Cattaneo. Forthcoming. Inequality and social protection.

● Stiglitz, Joseph E. 2010. The price of inequality. How today’s divided society endagers our future. Choice

Reviews Online 47 (11): 47-6385-47–6385.

● The Behavioural Insights Team. 2019. Reducing social security arrears in Indonesia.

● UN. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Right.

● United Nations. 2015. Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for

Development.

● Walsh, David, Ruth Dundas, Gerry McCartney, Marcia Gibson, and Rosie Seaman. 2022. Bearing the

burden of austerity: how do changing mortality rates in the UK compare between men and women?

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health: jech-2022-219645.

● World Inequality Lab. 2022. World Inequality Report.