Macroeconomic Effects of Public Pension

Reforms

Philippe Karam, Dirk Muir, Joana Pereira,

and Anita Tuladhar

WP/10/97

© 2010 International Monetary Fund WP/10/2

IMF Working Paper

Fiscal Affairs Department

Research Department

Macroeconomic Effects of Public Pension Reforms

Prepared by Philippe Karam, Dirk Muir, Joana Pereira, and Anita Tuladhar

1

Authorized for distribution by Benedict Clements, Manmohan Kumar, and Douglas Laxton

December 2010

Abstract

This Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF.

The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent

those of the IMF or IMF policy. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are

published to elicit comments and to further debate.

The paper explores the macroeconomic effects of three public pension reforms, namely an

increase in retirement age, a reduction in benefits and an increase in contribution rates. Using

a five-region version of the IMF‘s Global Integrated Monetary and Fiscal model (GIMF), we

find that public pension reforms can have a positive effect on growth in both the short run,

propelled by rising consumption, and in the long run, due to lower government debt

crowding in higher investment. We also find that a reform action undertaken cooperatively

by all regions results in larger output effects, reflecting stronger capital accumulation due to

higher world savings. An increase in the retirement age reform yields the strongest impact in

the short run, due to the demand effects of higher labor income and in the long run because

of supply effects.

JEL Classification Numbers:

H55, E6, H3, F41

Keywords:

OLG models, Aging, Pension Reforms, Fiscal Adjustment

Authors‘ E-Mail Addresses:

1

The authors are grateful to Carlo Cottarelli, Sanjeev Gupta, Benedict Clements, and Manmohan Kumar for

their guidance and to participants in the FAD seminar for useful comments. We thank Mauricio Soto for

providing pension spending projections in G-20 countries, Michael Kumhof for helpful discussions, Julia

Guerreiro for her assistance in compiling tax statistics, and Nadia Malikyar, Jeffrey Pichocki, and Mileva

Radisavljevic for help in formatting the paper. Special thanks to the Economic Modeling Unit of the Research

Department for sharing the GIMF‘s programs. Remaining errors are the authors‘ responsibility.

2

Contents Page

Introduction ................................................................................................................................4

I. Pension Spending Trends, Theory and Existing Studies ........................................................5

A. Current and Projected Public Pension Spending.......................................................5

B. Theory and Existing Studies .....................................................................................7

II. The Methodology For Modeling Public Pension Reforms ...................................................8

A. Overview of the Model‘s Key Features ....................................................................9

B. Quantifying Public Pension Reforms ......................................................................10

C. Caveats and Qualifications ......................................................................................12

D. Calibration ...............................................................................................................12

III. Results: Public Pension Reforms .......................................................................................13

A. Baseline ...................................................................................................................13

B. Region-by-Region Benchmark Public Pension Reform Scenarios .........................13

C. Benchmark Global Scenario—Simultaneous Reforms in all Regions ....................33

IV. Sensitivity Analysis ...........................................................................................................41

V. Conclusion ..........................................................................................................................42

Tables

1. Required Pension Age Extensions across the Regions ........................................................11

2. Cooperative Versus Regional Pension Reform—Increase in Retirement Age ....................38

3. Cooperative Versus Regional Pension Reform—Reducing Spending on

Pension Benefits...................................................................................................................39

4. Cooperative Versus Regional Pension Reform—Raising Contribution Rates ....................40

Figures

1. Change in Public Pension Expenditures, 2010–30 ................................................................6

2. Increase in the Retirement Age in the United States (Excluding Fiscal Consolidation) .....17

3. Increase in the Retirement Age in the United States ...........................................................18

4. Increase in the Retirement Age in the Euro Area ................................................................19

5. Increase in the Retirement Age in Emerging Asia ...............................................................20

6. Increase in the Retirement Age in the Remaining Countries Block ....................................21

7. Reducing Pension Benefits in the United States ..................................................................24

8. Reducing Pension Benefits in the Euro Area .......................................................................25

9. Reducing Pension Benefits in Emerging Asia .....................................................................26

10. Reducing Pension Benefits in the Remaining Countries Block.........................................27

11. Raising Contribution Rates in the United States................................................................29

12. Raising Contribution Rates in the Euro Area ....................................................................30

13. Raising Contribution Rates in Emerging Asia ...................................................................31

14. Raising Contribution Rates in the Remaining Countries Block ........................................32

3

15. Cooperative Versus Regional Pension Reform—Increase in Retirement Age ..................35

16. Cooperative Versus Regional Pension Reform—Reducing Pension Benefits ..................36

17. Cooperative Versus Regional Pension Reform—Raising Contribution Rates ..................37

18. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Coordinated Global Reform Scenario—

Labor Supply Response .....................................................................................................55

19. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Coordinated Global Reform

Scenario—Role of the Planning Horizon (Degree of Myopia) .........................................56

20. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Coordinated Global Reform Scenario—

Share of LIQ Households at 50 Percent Worldwide ...........................................................57

21. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Coordinated Global Reduction in Public

Pension Spending—Rapid Implementation .......................................................................58

22. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Coordinated Global Reduction in Public

Pension Spending—U.S. Reduction Levels Applied Globally ...........................................59

23. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Coordinated Global Reform Scenario—

Monetary Policy Accommodation .....................................................................................60

24. Sensitivity Analysis Around the Benchmark Reduction in Public Pension Spending by

the United States Only—Different Inflation Behaviors .....................................................61

Appendices

1. GIMF‘s Main Features and Calibration ...............................................................................44

2. Sensitivity Analysis .............................................................................................................51

Appendix Table

1. Selected Steady-State Values ...............................................................................................50

References ................................................................................................................................62

4

INTRODUCTION

The fiscal impact of the global crisis has reinforced the urgency of pension and health

entitlement reform.

2

Staff projections suggest that age-related outlays (pensions and health

spending) will rise by 4 to 5 percent of GDP in the advanced economies over the next

20 years, underscoring the need to take steps to stabilize these outlays in relation to GDP.

With the economic recovery not yet fully established, this paper emphasizes their short-run

macro impact in order to address concerns that these reforms can undermine short-run

growth.

3

We examine the preferred set of public pension reforms using the IMF's Global Integrated

Monetary and Fiscal (GIMF) model parameterized on data for five regions as representing

the entire world. We consider three policy reform options relating to pay-as-you-go public

pension systems that are commonly discussed in the literature. This analytical framework

allows us to approximately gauge the effects of these reforms on labor and capital markets

and growth in the short and long run.

4

(i) Raising the retirement age: this reduces lifetime

benefits paid to pensioners. Encouraging longer working lives with higher earned income

may lead to a reduction in saving and increase in consumption during working years. In

addition, increased fiscal saving will have long-run positive effects on output through

lowering the cost of capital and crowding in investment. (ii) Reducing pension benefits: this

increases agents‘ incentives to raise savings in order to avoid a sharper reduction in income

and consumption in retirement. It would reduce consumption in the short to medium run, but

would increase investment over the long run. (iii) Increasing contribution rates: this leads to

distortionary supply-side effects for labor, which combined with a negative aggregate

demand on real disposable income, depresses real activity in both the short and long run.

We assess how the policies compare in attaining the twin goals of strong, sustainable, and

balanced growth and fiscal stability (i.e., stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio against rising

pension entitlements). The key results show that increasing the retirement age has the largest

impact on growth compared to reducing benefits, while increasing contribution rates as

approximated by an increase in taxes on labor income has the least favorable effect on

output. Besides boosting domestic demand in the short run, lengthening working lives of

employees reduces the pressure on governments to cut pension benefits significantly or to

2

Pension and health entitlements already represent over a third of total spending in G-7 countries. Over the next

20 years, the net present value of pension spending increases alone is estimated at about 8 percent of GDP in

advanced and emerging countries. See IMF (2010a).

3

See Blanchard and Cottarelli (2010), ―The great false choice, stimulus or austerity,‖ Financial Times,

August 11 on attaining the twin goals of strong, sustainable, and balanced growth and fiscal stability.

4

Our analysis is undertaken relative to a ‗baseline‘ scenario, constructed such that an elevated long-run public-

debt-to-GDP ratio is reached in steady state based on staff‘s pension spending projections into the distant future.

5

raise payroll and labor income taxes. Reducing such benefits can lead to an increase in

private savings and an unwarranted weakening of a fragile domestic demand in the short run,

while raising taxes can distort incentives to supply labor. We also found that if regions

cooperate in pursuing fiscal reform, the impact will be greater than if only one or some of the

regions in the world undertake reform separately. In all, early and resolute action to reduce

future age-related spending or finance the spending could improve fiscal sustainability over

the medium run, significantly more if such reforms are enacted in a cooperative fashion.

The paper is organized as follows. Section II provides a background on past and projected

age-related pension outlays and discusses the reform options considered to offset them.

Section III provides a brief overview of the GIMF model while focusing on the details

pertinent to this exercise. Section IV presents the effects of the three different reforms taken

by each country at a time, then in all regions simultaneously. The global scenario highlights

the compounding effect of the reforms and their impact on external variables through trade

and (predominantly) financial spillover channels. Section V assesses in further detail the

possible reasons for the size of the macroeconomic impacts based on a sensitivity analysis

around the main results. Section VI concludes.

I. PENSION SPENDING TRENDS, THEORY AND EXISTING STUDIES

Age-related spending has been the main driver of current public spending increases over the

past two decades. These trends are expected to continue in the coming years for both

advanced and emerging economies pointing to needed entitlement reforms. Old-age

dependency ratios, which are already large in the advanced economies, particularly European

countries and Japan, are projected to double between 2009 and 2050, putting enormous

pressures on pension systems.

5

Furthermore, relatively high gross replacement rate of

pensions relative to average wages has also contributed to large pension spending and could

undermine the viability of pension system over the long run. In terms of contribution rates,

taxes on earnings are already high in a number of countries but in others, there is room for

raising payroll contribution rates (see IMF, 2010a). In this section, we examine the current

and projected pension spending and provide a short review and assessment of public pension

reform measures based on theory and existing studies.

A. Current and Projected Public Pension Spending

Within the advanced G-20 countries, pension outlays have risen by 1¼ percentage points of

GDP since 1990. Increases have been especially large for pensions in Japan and Korea in the

5

Based on the European Commission‘s Ageing Report (2009), it is evident that the anticipated demographic

transition will affect future pensions significantly. Despite recent pension reforms which may have strengthened

the counterbalancing impact of other factors, considerable spending pressures remain, however, in light of the

anticipated increase in dependency ratios.

6

past decade. Strong demographic factors were an important catalyst behind the increase in

pension outlays in France, Germany, Italy, and Japan where pension spending has already

surpassed 20 percent of total public spending. Looking forward, these trends are expected to

continue in all economies. Given the strong demographic pressures on these outlays,

reducing this spending would be difficult. A more realistic, if conservative, goal followed in

this paper would aim at stabilizing spending-to-GDP ratios—which would still require

significant structural reforms (IMF, 2010b).

Figure 1 shows pension spending projected to increase by an average of 1 percentage point

of GDP over the next 20 years. Large increases are projected in advanced countries that have

not substantially reformed their traditional pay-as-you-go systems, but in other advanced

economies, the increase would be less marked due to the projected impact of already

legislated reforms (IMF 2010a, Appendices IV and V). Adjustment needs may well be larger,

though, as the projections assume that these reforms will not be reversed, even when they

involve large cuts in replacement rates such as in Italy and Japan. Among emerging

economies, those with relatively high spending in 2010 are projected to experience the

steepest increase in outlays over the next 20 years. In other countries with currently low

coverage such as China and India, the projected increase is much less severe, but could rise

more rapidly if the system expands to cover a larger share of the population. Moreover,

beyond 2030, emerging economies are expected to experience a faster pace of aging

compared to the advanced economies.

Figure 1. Change in Public Pension Expenditures, 2010–30

(In percent of GDP)

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Luxembourg

Greece

Cyprus

Belgium

Finland

Slovenia

Norway

Netherlands

Iceland

New Zealand

Spain

Korea

Canada

Germany

Ireland

Australia

Denmark

Austria

United States

Malta

United Kingdom

Italy

Slovakia

France

Portugal

Czech Republic

Sweden

Japan

In percent of GDP

Advanced Economies

PPP Average: 1.1

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Ukraine

Turkey

Russia

Mexico

Romania

Lithuania

Malaysia

Saudi Arabia

Brazil

Latvia

South Africa

Philippines

India

Pakistan

Argentina

Indonesia

China

Hungary

Bulgaria

Estonia

Poland

In percent of GDP

Emerging Market Economies

PPP Average: 1.1

Sources: Country authorities; EC (2009); OECD (2009); ILO (2010); and IMF staff estimates.

7

B. Theory and Existing Studies

A large body of research exists on fiscal consolidation in the face of demographic shifts and

the impact of public pension system reforms on growth and public debt dynamics. We focus

on three key reforms: (i) raising the retirement age, (ii) reducing benefits, and (iii) increasing

contribution rates.

Raising retirement age raises participation in the labor force beyond a certain age and slows

down the increase in the pension system dependency ratio.

6

This leads to a reduction in

transfer payments to pensioners, an increase in contributions and an increase in tax revenues

through increased income and consumption, therefore leading to higher public savings. In the

long run, output rises as firms demand more capital inputs to work with higher labor. Before

retirement, forward-looking consumers who will be providing more labor services and face a

shorter retirement period reduce their saving and increase consumption in anticipation of

increased future income. Earning income over a longer working period makes up for this

initial drop in savings and has a positive impact on their stock of wealth in the long run.

Reducing benefits has been the policy choice of several countries, with cuts of nearly

20 percent or more set to occur within the next 20 years. Benefits could be reduced by

modifying the base used to calculate benefits, modifying indexation rules, or taxing pensions.

Rules that link benefits to demographic and economic variables to maintain actuarial balance

could also lead to benefit cuts.

7

Based on theory, there are strong incentives for working

households to increase their savings in the face of announced decline in replacement rates of

the pension regime, in order to avoid a sharp reduction in their income and consumption after

retirement. A higher saving rate leads to stronger capital accumulation and an improvement

in the net asset position of the country, but the effect on short- and medium-run consumption

levels can be negative.

Increasing contribution rates needs to be assessed along with potential changes in the tax

rate on labor income, since it is their combination that determines the effective marginal and

average tax rates that are likely to affect decisions about labor participation and hours

worked.

8

These incentive effects of social contributions, however, might be less marked if

6

In this paper, raising the retirement age by a year induces individuals to effectively work one year longer on

average. This would cover those that retire at an age with full retirement benefits and those that choose early

retirement. It assumes that replacement rates stay constant, implying a decrease in total lifetime pension benefits

(see Section IV).

7

For example, in Japan, ‗macro indexing‘ is achieved by reducing pensionable earnings and benefits by the rate

of decrease in the number of contributors and increase in life expectancy at age 65. In Canada, benefits are

required to be reduced, or contributions increased, to address long-term actuarial imbalances.

8

A richer menu of taxation would allow a further distinction between personal income tax levied on labor and

social security contributions paid by workers and employees. Changing payroll tax on workers vis-à-vis

changing personal income tax can have different distortionary effects. We abstract from these details here.

8

their payment is seen as implying increased benefit entitlement. Overall, offsetting the

spending pressures from the pay-as-you-go regime based on an increase in contribution rates

usually reduces the potential output of the economy by distorting labor supply. A demand

effect through households‘ lower disposable income also adds to the negative impact of this

option.

Empirical findings on the other hand appear to be inconclusive, reflecting perhaps country-

specific and empirical methodology differences. Botman and Kumar (2007) look at age-

related reforms, but focused exclusively on the European Union (with Germany as an

example). They also analyze the impact of broader structural reforms, such as increasing

labor participation, product market liberalization, and higher R&D to help increase

productivity and find positive output effects in the short run. Nickel and others (2008) show

that timely tax-cut measures can moderate the adverse effect on consumption (and encourage

labor supply) of future announcement of cuts in pension benefits, and lower public debt;

while increasing retirement age, without cutting pension benefits, fails to lower public debt.

9

In contrast, Cournède and Gonand (2006) and Andersen (2008a, b) find that raising

retirement age is optimal based on a likely boost in growth and improved public debt

dynamics. Real GDP growth is stronger when rebalancing the pension regime by increasing

the retirement age (and containing spending) rather than lowering replacement rates and

raising taxes. Barrell and others (2009) have also demonstrated an improvement in public

debt dynamics following an increase in effective working life (for the United Kingdom and

the euro area countries taken together). As workers know that they will work longer, they

save less now and increase their consumption ahead of the prospective income increase. Over

the long run, labor and capital rise leading to an increase in GDP. Importantly, under constant

tax rates and spending, increasing the pension age would result in reduced budget deficits

and public indebtedness in European economies, on average.

II. THE METHODOLOGY FOR MODELING PUBLIC PENSION REFORMS

This section provides a summary of the methodology followed in addressing the aging-

related reforms of public finances, while strictly focusing on the main features of the model‘s

sectors (households, firms, and government) and parameters which have a direct and relevant

impact on our analysis.

10

Caveats and areas for future work remain given that the model, like

most others cannot reflect all complexities that can influence the effect of the considered

reform policies.

9

While the finding that a tax decrease aimed at offsetting the age-related fiscal consolidation effect on

consumption and labor is sensible, it should be assessed in light of the current situation with mounting fears of

unstable debt dynamics.

10

Appendix 1 provides further explanation of the sectors and the optimization involved. For a fuller exposition

of GIMF‘s properties and calibration, see Kumhof and others, KLMM (2010).

9

A. Overview of the Model’s Key Features

We use GIMF, a dynamic stochastic general equilibrium model widely used inside the Fund,

as a framework for analyzing the short- and long-run effects of the planned pension policy

actions. Key in analyzing the positive aspects of achieving fiscal sustainability in the face of

aging as well as the normative aspects of adjusting public policies to changes in

demographics, is GIMF‘s underlying overlapping generations‘ and finite horizons‘ structure.

It produces meaningful medium- and long-run crowding-out effects of government debt and

captures important life cycle income patterns, including age-dependent labor productivity.

Moreover, labor and capital markets are endogenous—the first allowing labor income taxes

to have distortionary effects and the latter providing an important channel through which

government debt crowds out economic activity. As such, a realistic supply side enables us to

consider the impact of public pension reforms on investment decisions.

The multi-country structure of GIMF allows an analysis of global interdependence and

spillover effects. The world in this model consists of five regions, the United States (US), the

euro area (EU), Japan (JA), emerging Asia (AS),

11

and remaining countries (RC). The

regions trade with each other at the levels of intermediate and final goods, with a matrix of

bilateral trade flows based on recent historical averages. International asset trade is limited to

nominally non-contingent bonds denominated in U.S. dollars. Importantly, the link between

regions through international financial markets provides the key channel for spillover effect

of aging-related spending at a global level while adding realism to the macro outlook and the

impact of policy response. The financial spillover effect is likely to dominate the trade

channel because of the compounding effects of cooperative public pension reform on real

interest rates, which in turn affect the cost of borrowing and overall debt dynamics

(Section IV.C.).

To emphasize the potential interaction role of fiscal and monetary policies, GIMF combines

sufficient non-Ricardian features with a number of nominal and real adjustment costs, such

that short-run dynamics of the model would be determined by the interaction of both of these

policies while longer-run dynamics are influenced mainly by fiscal policy. This combination

is missing from other new-open-economy macroeconomic models and fiscal models,

including the IMF‘s Global Fiscal Model (GFM).

There are three groups of agents and sectors in the model: households, firms, and the

government.

11

AS comprises China, Hong Kong S.A.R. of China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore,

and Thailand. For pension projections below a subset of those countries is considered, comprising China, India,

Indonesia, and Korea.

10

In the households sector, three parameters of interest determine the degree of non-Ricardian

behavior of agents:

,

and

.

is the share of liquidity-constrained households (LIQ) in

the economy, without access to financial markets, that are limited to consuming their

after-tax income in every period. The size of this group, assumed to differ significantly

across economic regions, can be crucial to the analysis of the effects of the labor income tax

reform measure for instance, as will be seen later. The remainder of the households, are

overlapping generations (OLG) households, who are fully optimizing agents. Each of these

agents faces a constant probability of death

1

in each period, which implies an average

planning horizon of

1/ 1

. In addition to the probability of death, households also

experience labor productivity (and hence labor income) that declines at a constant rate

over their lifetimes. Life cycle income adds another powerful channel through which fiscal

policies have non-Ricardian effects, as this along with

(probability of survival) produce a

high degree of myopia. Households of both types are subject to labor income, consumption

and lump-sum taxes and the presence of these taxes along with transfers and government

spending (see fiscal policy block in Appendix 1) allows us to relate the pension-related tax

and expenditure reforms to specific model‘s parameters and variables.

In order to represent an increase in retirement age in GIMF, we rely on two parameters in

particular:

(which corresponds to a decline in labor productivity over an average working

life—it defines agents‘ ―income profile‖) and

N

(which is an index of the population size

assumed to correspond to population of the work force age, ages 15 to 64).

Firms are managed in accordance with the preferences of their owners, myopic

OLG

households, and they therefore also have finite-planning horizons.

Government’s intertemporal budget constraint is discussed in Appendix 1. We suffice by

highlighting the role of fiscal policy in stabilizing deficits and the business cycle, through a

typical fiscal rule. The latter stabilizes the government deficit-to-GDP ratio at a long-run

target (structural) level, which rules out default and fiscal dominance (dynamic stability).

It also stabilizes the business cycle by letting the deficit fall with the output gap. Finally,

monetary policy in the model is based on an inflation-forecast-based interest rate reaction

function in which the central bank sets interest rates in order to stabilize inflation at an

announced target level.

B. Quantifying Public Pension Reforms

For all public pension reform measures, we use 2014 as the starting point for our benchmark

scenario. This is near the end of the current version of the IMF‘s World Economic Outlook,

when most economies are forecasted to have returned to stable output gaps around zero, and

inflation close to their target levels. Starting from such a position, pension reforms are likely

to generate short-run increases in output leading to a monetary policy reaction (as will be

11

seen in Figure 15 later). However, we also assess how the results might change if monetary

policy remained accommodative for a year or two, as a pre-announced and conscious

decision to accommodate a stimulative fiscal policy measure. This is dealt with in the

sensitivity analysis Section V. The results below show that delaying a monetary policy action

would boost short-run consumption and real GDP (considerably more relative to the

benchmark), and public finances improve as government deficits decline faster in light of

lower debt service payments. When normal conduct of monetary policy returns, there is the

usual dampening effect on demand in the medium run (Section V and Appendix 2).

We consider differentiated retirement age increases which are sufficient to stabilize pension

spending as a share of GDP at its 2014 level, over the next three to four decades. Differences

in necessary retirement age increases stem from different baseline projections of the pension

gap (size determined exogenously based on country-specific demographics and pension

parameters) across the five regions, implying different consolidation needs such that the

resulting debt trajectory as a share of GDP is stabilized. Based on staff estimates of the

projected pension spending in the five regions, the required ‗pension age extension‘ is shown

in Table 1. The estimates suggest, for instance, that Japan would not require additional

reforms.

Table 1. Required Pension Age Extensions across the Regions

US

JA

AS

EU

RC

(Number of years)

2015–2030

2.5

...

1.0

1.5

3.0

2030–2050

0.0

...

0.5

0.5

1.5

Source: IMF (2010a) and staff estimates.

In line with the change in the lifetime income horizon, we implement a two-year extension of

working lives on average, globally, by lengthening agents‘ income profile (

), and assuming

an increase in the working-age population (N).

12

The income profile is assumed to increase

immediately following the start of the reform, with the labor force gradually increasing over

the next 15 years. The increase in the income profile is consistent with a decrease of private

saving as a percent of GDP, as found in studies focused on European countries.

13

Both

measures are consistent with a gradual phase in of increases in retirement age as well as

12

In GIMF, by assuming that the working-age population spans the ages 15–64, a two-year extension is roughly

equivalent to a 4 percent increase in this population size. This can be made more moderate, since cohorts

usually congregate near the middle of the age distribution (or in the case of aging Western societies, between

40 to 60 years old).

13

See, in particular, Khoman and Weale (2008) and Barrell and others (2009).

12

evidence which suggests that agents react by delaying retirement (several years ahead of the

change itself) thereby leading to an increase in labor supply over their lifetime horizon.

The two other considered reform options, a reduction in pension benefit payments and an

increase in contribution rates, are simply modeled as non-distortionary lump-sum transfers

to all households and an increase in the labor income tax rate, respectively.

C. Caveats and Qualifications

The fiscal block of the GIMF model does not allow for an explicit breakdown of working-

age and retired population,

14

nor does it feature an elaborate pay-as-you-go pension regime.

In light of this, it is not possible to interpret a rising dependency ratio as due to reduced

fertility or increased longevity. Other issues like labor force perception of the pension system

as a tax-and-transfer system versus an insurance mechanism, and movement to more

actuarially-based public programmes

15

may affect individuals‘ saving and labor supply

behavior differently, influencing in turn the normative assessment of reform—we leave these

interesting extensions for future work. But unlike other large simulation models dealing with

full-blown demographics and pension systems which may complicate the interpretation of

results, GIMF focuses on the dynamics and long-run equilibrium of the main variables in a

transparent way, and these dynamics and equilibria can be changed by modifying a few

essential parameters. The structure is flexible enough to compensate for missing households

who ‗really‘ retire by treating an extension of working lives with regard to agents‘ income

profile coupled with a potential increase in ‗working age‘ population.

Another caveat lies in examining the contribution rate hike scenario which we proxy by an

increase in the labor income tax rate. This can be seen as a lower bound on this issue, since

we have only captured the effect on the labor supply decision and not the direct effects on

labor demand from higher contributions by employers. The decline in pension payments to

retirees is then captured through lower pension transfers and pension deficits.

D. Calibration

Relevant steady state ratios and parameters of particular importance for this exercise are

discussed in Appendix 1, with a brief summary of the important ratios provided in Appendix

Table 1. The model is calibrated to reflect key macro features in the five regional blocs

(including key expenditure ratios of consumption, government, investment, net exports, and

14

Changes in the population structure are not captured in a detailed way in GIMF compared to models with a

richer cohort distribution. A change in participation rate of older workers is calibrated in GIMF through some

relative measures of working-age population, as discussed.

15

This is a purely design question of social security programmes, to emulate a private retirement saving plan.

See Disney (2005).

13

factor incomes) as well as key fiscal variables reflecting the fiscal structure of the regional

blocs (revenues and spending, net debt- and deficit-to-GDP ratios). More detailed calibration

tables are presented in KLMM (2010). Unless otherwise stated, similar behavioral parameter

values apply to all regions and are based on microeconomic evidence. We use an annual

version of the model because the critical pension-related fiscal issues stressed are of a

medium- to long-run nature.

Calibrated government debt-to-GDP ratios are based on 2014 net debt projections for the

five regions from the IMF's World Economic Outlook Update, February 2010 (IMF, 2010c)

but have taken into account the mounting pressure of pension gaps. The real global growth

rate is 2.5 percent, the global population growth is 0.5 percent, and the long-run global real

interest rate is 4.0 percent.

III. RESULTS: PUBLIC PENSION REFORMS

A. Baseline

The baseline scenario is based on the IMF‘s February 2010 World Economic Outlook for

public debt in G-20 countries, up to 2014–15, close to what the May 2010 update shows. It is

also based on Fiscal Affairs Department staff‘s projections of public pension spending and

primary fiscal balances over the next four decades, which translate in a very distant future

into higher steady state debt-to-GDP ratios and a higher world real interest rate than usually

used in GIMF.

B. Region-by-Region Benchmark Public Pension Reform Scenarios

This section discusses the effect of reforms undertaken in each region on its own, beginning

in 2014. While similar behavioral parameter values apply to all regions, country-specific

variation in the demographics is reflected in the size and pace of the adjustment as described

in Table 1 above. Such an individual action is then compared to a cooperative action (albeit

still allowing for country differences) in Section IV.C.

Three reform options relating to pay-as-you-go public pension systems are assessed. They

are broadly equivalent in terms of their fiscal impact, all of them being broadly sufficient to

offset the projected increase in pension spending over the long run, excluding their possible

and distinct effect on growth. With the economic recovery still under way, it is important to

assess the short- and medium-run impact of such reforms on the pace of activity as well as

their budgetary impact. Results show that the type of reform matters: increasing the

retirement age has the largest positive impact on real GDP, while increasing contribution

rates has the least favorable effect on output.

16

16

As will be seen, while pension gaps are reduced steadily with the adoption of any of the planned pension

reforms discussed below, we observe that along the transition path to higher long-run real GDP, the short-run

(continued…)

14

Increasing retirement age

To anticipate the results, increases in the retirement age are the most effective tool: on

average across regions, raising the retirement age by two years on average

17

would raise

GDP by almost 1 percent in the short to medium run and 4¼ percent by 2050 above the

baseline scenario. It reduces the debt-to-GDP ratio by 30 percentage points over the same

period.

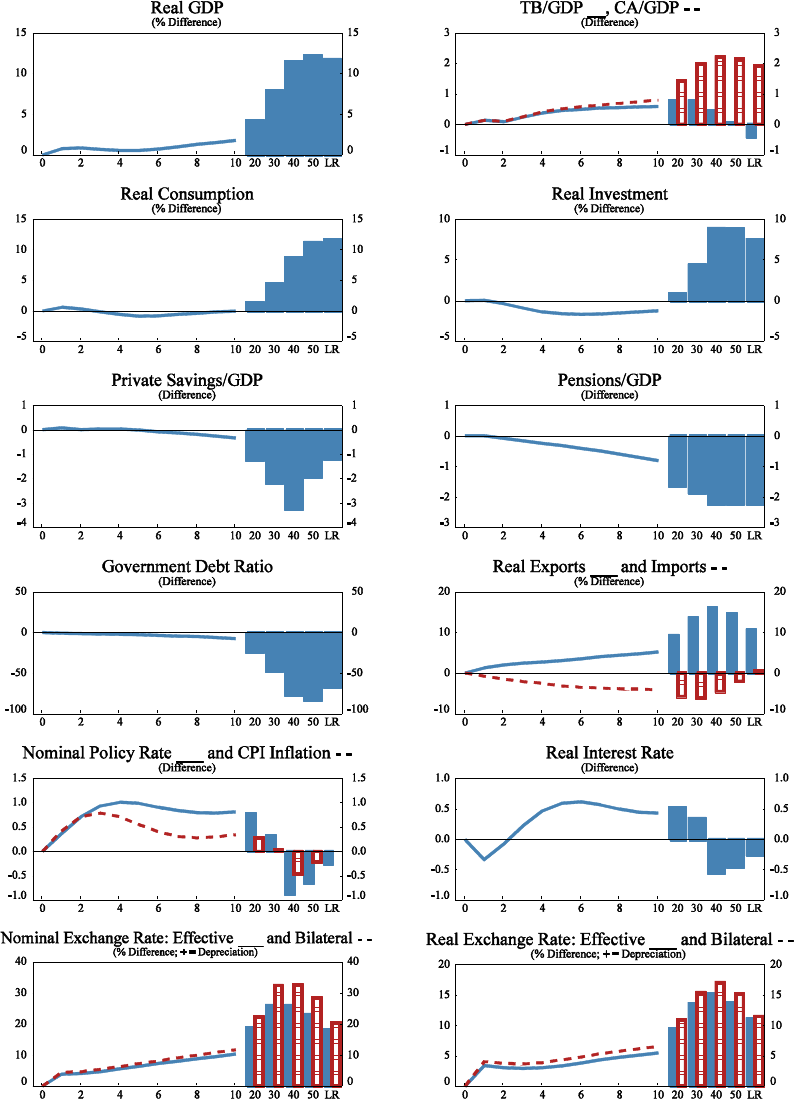

Figure 2 illustrates the effect on the United States of an increase in retirement age in the

United States alone, while first keeping public pension spending (transfers) constant. As

expected, a delay in the retirement age boosts labor supply and labor income. Agents reduce

their saving and their demand for assets during working years, while increasing consumption.

Future earning incomes over a longer working period are higher and are brought forward

through higher consumption by optimizing agents. The private saving rate as a ratio of GDP

declines immediately by 0.2 percentage points, while consumption rises above baseline by

close to 2 percentage points in the short run, preceding the increase in real GDP.

18

In the

short run, the increase in real GDP is 0.75 percent above baseline in period 2, and public

finances improve slightly (the debt-to-GDP ratio is only 4 percentage points below baseline

after 20 periods), a direct result of increased tax revenue collected on income and

consumption. Considering Figure 2 alone, despite providing a partial analysis of the overall

reform scenario (no implied transfer reductions are modeled thus far), it gives a clear

interpretation of the boost in consumption as stemming from an increase in lifetime income

horizon (the effect of which is brought forward) and working age population. A cut in

benefits as embedded in Figure 3, will dampen this effect.

Figure 3 depicts the complete analysis of this reform as the concurrent fiscal consolidation

implied by the cuts in public pension spending, as the number of years over which pensions

are paid are reduced, is added to Figure 2. The budget deficit improves as a result by close to

3 percentage points of GDP after 30 years and settles around 2.2 percentage points once

reached in the long run, given the target we impose in the distant future. Equivalently, the

debt-to-GDP ratio declines by roughly 43 percentage points in the long run—more than

tenfold the improvement shown in Figure 2. At the same time, a lower government debt

which is perceived as a decline in

OLG

agents‘ net wealth along with the decline in transfer

dynamics of the macroeconomic adjustment differ substantially. Size, speed, and timing of the fiscal

consolidation plan, alongside the incentive effect of reforms on consumption and savings all play a role.

17

The two-year average reflects variation across regions in the increase in the retirement age needed to stabilize

the debt-to-GDP ratio against rising pension entitlements.

18

Such a strong response in labor supply is assumed to be absorbed quickly with minimal effect on the

unemployment rate and the associated unemployment benefits to be paid by the government.

15

payments (with a more pronounced effect on

LIQ

agents) both work to depress consumption

markedly, which now only rises modestly above baseline, compared to Figure 2.

In the short run, there is a tightening of interest rates (by 80 basis points in year 4) in

response to inflationary pressure emanating from a short-run increase in domestic demand.

As the demand pressures continue from the stimulative increase in labor supply, the

monetary authority maintains a tight stance for a long period. This interest rate effect

dampens domestic demand in the short run. But in the medium to long run, investment is

boosted as real interest rates fall in response to the fiscal consolidation, leading to visible

improvement in output. In addition, output rises with the increase in labor supply (and a fall

in marginal cost from the falling real wage) which in turn attracts more capital. This rises

marginally less than labor supply

19

and output continues on an upward trend, reaching over

3.5 percent above baseline in the long run.

Discussing next the external variables, if we only focus on the effect of the increase in the

retirement age without the fiscal adjustment (Figure 2), the United States experiences an

appreciation of the real exchange rate, and, therefore, a deterioration in the trade balance and

the current account. Here, the saving-investment perspective predominates, as real wages

decline (as more labor is supplied), the higher return on capital attracts capital inflows and

leads to a current account deficit which needs to be closed through a depreciation in the

exchange rate. However, the effect on external variables is dominated by the fiscal

consolidation that is occurring simultaneously (Figure 3). Now, lower real interest rates from

increased world saving crowds in investment in external assets, leading to an accumulation of

net foreign assets. In the very long run, with declining interest payments to foreigners,

current balances are above baseline which means that the real effective exchange rate begins

appreciating again. However, relative to the baseline, the real effective exchange rate has

depreciated, albeit much less in 50 years into the future, relative to only 30.

Figures 4 to 6 show the same ‗package‘ of reforms (akin to Figure 3) being undertaken by

each of the three other regions facing notable challenges to their pension systems—the euro

area, emerging Asia, and remaining countries (recall, in the case of Japan, no pension age

extension was needed). Although the quantitative results are different, the story behind each

scenario is intrinsically the same as that of the United States, with some qualification.

For the euro area (Figure 4), results are qualitatively similar to the United States, but there is

a smaller required pension-age increase to attain given budgetary saving (this is primarily

due to the fact that in the euro area a pensioner receives on average larger benefits), more

rigid prices and a more aggressive monetary rule, leading to a weaker consumption profile

19

Private capital rises less than employment due to an expected marginal upward pressure on interest rates from

increased demand which may lead to a partial crowding-out.

16

relative to the United States, in the short run.

20

Over the long run, consumption improves by

more as pension transfers are cut more aggressively in the later periods, bringing with them a

larger drop in interest rates, and therefore lower debt level (close to 47 percentage points

below baseline). Driven by higher domestic demand, real GDP rises 5.8 percent above

baseline.

An exception is emerging Asia, because it pursues a fixed nominal exchange rate vis-à-vis

the United States, instead of inflation targeting. In this case (Figure 5), there is a depreciation

of the real exchange rate, as occurs in the cases of other regions such as the United States

(Figure 3) or the euro area (Figure 4). But emerging Asia‘s nominal exchange rate peg

constrains them to importing their short-run interest rate profile from the United States (as

uncovered interest rate parity holds in GIMF). In order that the real effective exchange rate in

emerging Asia depreciates in the long run, there will be downward pressure on domestic

prices, resulting in sustained disinflation, relative to the baseline scenario. Here, GIMF may

overstate the actual inflation and interest rate dynamics in emerging Asia, as there is no role

for capital or credit controls, which may play some role in the actual conduct of exchange

rate policy.

This story related to the conduct of monetary policy in emerging Asia will also hold in the

other two public pension reform options discussed below. A policy aiming at greater

exchange rate flexibility in emerging Asia over the medium run, whether through a nominal

appreciation or through higher inflation is not assessed here.

20

A stylized Taylor-type interest rate reaction function is adopted, where the central bank adjusts the policy rate

on the basis of the deviation of inflation from its target to stabilize inflation at a pre-specified target level. The

rule matters in the response to offset inflationary pressures arising from a boost in domestic activity. A

persistent underlying inflation process with monetary policy being tightened as a result would put downward

pressure on growth. Reduced price rigidities can mitigate this effect by effectively speeding the response of

inflation and shortening the period of tighter policy. Delaying the response of monetary policy will also boost

short-run consumption and real GDP (for further clarification, please see Section V and Appendix 2).

Moreover, while the size and time profile of the fiscal adjustment play a role, initial conditions and market

responses to the adjustment plans are crucial.

17

Figure 2. Increase in the Retirement Age in the United States

(Excluding Fiscal Consolidation)

18

Figure 3. Increase in the Retirement Age in the United States

19

Figure 4. Increase in the Retirement Age in the Euro Area

20

Figure 5. Increase in the Retirement Age in Emerging Asia

21

Figure 6. Increase in the Retirement Age in the Remaining Countries Block

22

Reducing benefits

21

This reform generates rewards over time following the transitory short-run initial costs of

fiscal tightening on aggregate demand. Consider if the decline in benefit payments (and the

consequent decline in government debt) occurs only in the United States. Figure 7 shows the

simulated effects of reduced government debt-to-GDP ratio brought about by decreases in

pension benefit payments (that behave in GIMF as non-distortionary lump-sum transfers) to

reverse past promises of enlarged public pension spending. Although consumption drops by

about 1 percent below baseline in the short run, this is largely outweighed by the persistent

benefits of lower real interest rates and higher real GDP—over time, real GDP rises and

settles at a higher level in the long run, almost 0.5 percent above the baseline scenario.

World real interest rates decline, moderately, beginning in period 10, before they hit a trough

close to -0.4 percentage points below the baseline after 40 years.

22

Such an effect is

transmitted to the global economy with all countries experiencing a boom in investment,

varying between 0.5 and 2 percent in the euro area and emerging Asia, respectively, and a

permanent expansion in real GDP, varying between 0.3 to 0.5 percent. In sum, the U.S.

policy scenario generates a positive and large effect in other regions as long-run real interest

rates are equalized internationally to a lower level and capital investment is boosted.

So, following a reduction in pension benefit payments, U.S. domestic demand (consumption

and investment) decreases for a rather prolonged period of time, while real GDP experiences

an uptick for a brief period,

23

buoyed by improved external balances, but decreases

moderately thereafter before increasing and settling at higher levels in the long run.

Consumption declines in light of the non-Ricardian nature of the model whereby a fiscal

consolidation reduces the net wealth of

OLG

agents (as the value of taxes for which they are

now expected to be responsible has increased, if taxes were to be used as an instrument). For

a given marginal propensity to consume, these reductions in (human) wealth lead to a

reduction in consumption, accompanied by a decline in real interest rates. During the initial

phase, real interest rates are predominantly driven by the monetary policy response to excess

21

The average reduction in benefit payments is high exceeding 20 percent as driven by large projected pension

spending in the remaining countries block. This differs across regions depending on the savings needed to

stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio against rising pension entitlements.

22

Potentially reduced sovereign risk premia associated with favorable market responses to improved public

finances, as a result of pension reform, are not taken into account.

23

The short-lived increase in GDP occurs since demand for foreign goods (imports) falls rapidly in response to

the quick movement in the real exchange rate (a property of the standard risk-adjusted uncovered interest rate

parity condition determining exchange rate), but domestic demand falls more slowly, as it is driven by the

slower decline from the fiscal consolidation. In other words, imports fall more quickly than consumption and

investment, and this, by simple accounting, leads to higher real GDP.

23

supply in the economy and deviation of inflation from target. Externally, reduced import

demand (part of the consumption demand decline is absorbed by trading partners) leads to

improvement in trade balances and a real depreciation.

Over the longer run, real GDP increases relative to the baseline. Higher fiscal saving leads to

an increase in both in U.S. and world savings, given the size of the U.S. economy. Real

interest rates decline by close to 40 basis points in order to re-equilibrate world saving and

investment. The non-Ricardian

OLG

structure of the model and the endogenous capital

formation provide the channels through which government debt crowds in investment in U.S.

physical capital, so that real output increases. Moreover, agents‘ decreased investment in

government debt instruments frees up resources to other forms of investment, including

foreign assets. This implies that current balances improve subsequently necessitating a real

appreciation in the exchange rate, which only comes gradually.

In other regions (euro area, emerging Asia, and the remaining countries block) which

undertake similar reforms, the effects are similar (Figures 8 to 10). However, the spillover

effects are different as they are driven by their responsiveness to movements in the world real

interest rate. For instance, the spillover effects of reforms initiated by a large economic

region (i.e., the United States or the euro area) on other regions‘ real GDP is four times the

spillover effect if a smaller region (i.e., emerging Asia constitutes is calibrated in GIMF to be

13 percent of world nominal GDP, versus 27 percent for the United States) undertakes

reforms, since a smaller region will have less of a long-run impact on world interest rates,

and by extension on investment and output on those regions which do not undergo reform.

24

Figure 7. Reducing Pension Benefits in the United States

25

Figure 8. Reducing Pension Benefits in the Euro Area

26

Figure 9. Reducing Pension Benefits in Emerging Asia

27

Figure 10. Reducing Pension Benefits in the Remaining Countries Block

28

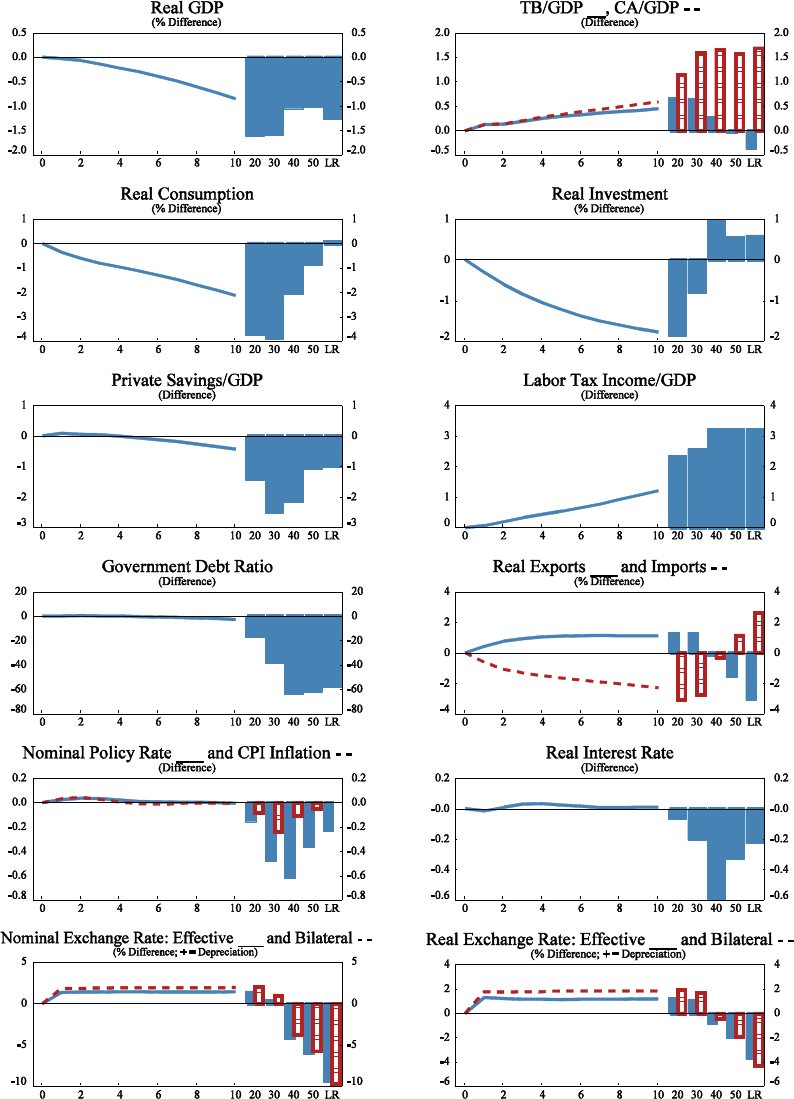

Raising contribution rates

24

We proxy the increase in contribution rates in GIMF, by considering an increase in the labor

income tax rate, in this case, the United States only (Figure 11). Consequently, there is a

decline in the supply of labor with negative effects on actual and potential output. Besides

this supply-side effect, this policy measure affects the demand side of the economy indirectly

through a decline in households‘ real disposable income—this income and wealth effect is an

important channel given the myopic nature of both

LIQ

and

OLG

agents (in light of the

planning horizon parameter and

finite remaining working life of 20 years on average).

Given that the

LIQ

households consume at most their after-tax current income, the size of

this group, which is assumed to be significantly different across economic regions, is critical

for the analysis of this labor income tax measure. Moreover, a decline in potential output is

likely to exert upward pressure on inflation. In all, the effect on U.S. real GDP is notably

worse than in the benefit-reduction scenario in the short run, and even in the long run. This

should not be surprising, since GIMF, like most models in the literature, find that the

multiplier effect of a change in the labor income tax rate is higher than an equivalent shift in

a lump-sum transfer, such as a pension benefit cut (Coenen and others, 2010).

Therefore, the results of this form of public pension reform are similar to those found under a

cut in pension benefits, but the distortionary nature of this reform means the short-run losses

are more significant—real GDP declines by about 0.7 percent below baseline by period 10.

The negative effect of distortionary taxes on potential output also means significant losses in

the long run. Also, the consequent decrease in the real world interest rate does not play as

effective a role in raising real GDP in the long run as in scenario 2 above—real GDP remains

close to 0.4 percent below baseline versus an increase of 0.4 percent when cuts in pension

benefits are the fiscal measure of choice.

Once again, these results also hold in the other three regions, the euro area, emerging Asia,

and the remaining countries block (Figures 12–14).

24

On average, the necessary increase in contribution rates is 2¾ percentage points or over 10 percent. Again,

this differs across regions depending on the requirement to stabilize the debt ratio against rising pension

entitlements.

29

Figure 11. Raising Contribution Rates in the United States

30

Figure 12. Raising Contribution Rates in the Euro Area

31

Figure 13. Raising Contribution Rates in Emerging Asia

32

Figure 14. Raising Contribution Rates in the Remaining Countries Block

33

C. Benchmark Global Scenario—Simultaneous Reforms in all Regions

A cooperative strategy to pursuing fiscal reform has a larger impact on output and fiscal

sustainability than if regions undertake reform alone. The cooperative benefit is greater than

the sum of individual country/region benefits. The magnification effect of global reforms on

key variables is driven by the significantly stronger decline in the world real interest rate

corresponding to larger compounding effect on word savings under the cooperative strategy.

Thus far, we have only considered reforms in each region of the world in isolation. While it

is in each country‘s interest to pursue reforms regardless of what other countries or regions

do, there can be a clear advantage from promoting global policy cooperation. In the cases of

individual action, the effects of the policy measure will often leak abroad, which, while

benefitting other regions, reduces the potential impact domestically. Countries can simply

delay reforms and free ride on adjustments undertaken elsewhere.

25

Faced with a common

and an unavoidable demographic shift and a future of possibly muted growth and high

unemployment, cooperative action for public pension reform among all regions can be key.

Cooperation can buttress the twin goals of growth and fiscal stability by stabilizing the

debt-to-GDP ratio against rising pension entitlements. It is expected that the world real

interest rate will over time change by more than when an individual region engages in reform

alone, which leads to a larger effect on capital accumulation and potential and actual output

levels in the long run.

Figure 15 clearly shows those benefits by looking at the effects on the United States when it

undertakes an increase in retirement age pension reform alone (the right column), versus a

cooperative global effort (the left column), both beginning in 2014. Under the cooperative

case, real GDP is 50 percent higher in the long run. A cooperative action results in an interest

rate decline that is about five times that under an individual action. As a result, a permanent

expansion in real GDP worldwide (average over the five regions) in the order of 7.2 percent

above baseline follows (Table 2)—this table also shows that this is about 40 percent larger

than the sum of benefits from individual country reforms.

The magnified effects of simultaneous public pension reforms by all regions, relative to

reform by each region alone, are further illustrated in Table 2 (the increase in retirement age

case). It highlights the effect of reform on real GDP, consumption, the real interest rate, and

the government debt-to-GDP ratio in the five regions, which are clearly larger in every case

under a cooperative policy action (the first set of rows) versus the individual action (the

second through fifth set of rows). While all regions benefit relatively more from a

25

Botman and Kumar (2007) analyze the macroeconomic effects of a coordinated policy response to global

demographic pressures in a four-country version of GFM (Germany, the rest of the euro area, the United States,

and the rest of the world) and show clear benefits from a cooperative fiscal adjustment. Freedman and others

(2009a,b) also show the benefits of a coordinated approach to fiscal activism in a GIMF setting.

34

cooperative action, the euro area, a large and relatively less open region benefits relatively

less than a smaller and more open emerging Asia (40 percent and 110 percent improvement,

respectively).

Figures 16 and 17 make a similar point for the other two policy options. In the case of an

increase in labor income taxes to finance the pension gap, real GDP no longer falls relative

to the baseline scenario in the long run. However, real GDP in the United States in this case

increases by only 0.5 percent, while rising above baseline by more than three times that

amount in the long run (1.6 percent) if the fiscal measure was a decrease in pension benefits.

Tables 3 and 4 summarize the results of these corresponding reforms if carried out

individually (along with their spillover effects into other regions) or globally.

To sum up, promoting a global cooperative increase in retirement age appears to yield the

largest impact on activity—the relative improvement in real GDP worldwide is four and over

10 times larger than under reform options 2 and 3.

In terms of external balances, the global cooperative scenario yields a weaker external

balance in each country, and corresponding less accumulation of net foreign assets. The

current account improves by less under a cooperative action than when a policy is taken by

each country or region on its own. Under a global scenario where only one country does not

reform, improvements in the current account balances of the reforming countries would be

reflected in a deteriorating balance of the non-reformer—private saving declines or

consumption rises due to an appreciating real exchange rate and an investment rises due to

lower interest rates.

As for improving public finances, stabilizing the GDP share of age-related (pension)

expenditures leads to a sizable decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Early and resolute action to

reduce future age-related spending could significantly improve fiscal sustainability in several

countries over the medium run and more so if such reforms are again enacted in a

cooperative fashion; for instance, debt-to-GDP ratios decline by 40 to 50 percentage points

(depending on the undertaken reform) below baseline on average across the regions, an

improvement of approximately 30 percent relative to a non-cooperative strategy

(Tables 2–4). This is due to the magnified effect of fiscal consolidation efforts on world

savings and world real interest rates with larger attendant crowd-in effect on investment.

35

Figure 15. Cooperative Versus Regional Public Pension Reform—Increase in

Retirement Age

36

Figure 16. Cooperative Versus Regional Public Pension Reform—Reducing

Pension Benefits

37

Figure 17. Cooperative Versus Regional Public Pension Reform—Raising

Contribution Rates

38

Table 2. Cooperative Versus Regional Public Pension Reform—Increase in

Retirement Age

US

EU

JA

AS

RC

Global Scenario

Real GDP

5.4

7.9

2.1

7.2

13.5

Consumption

6.4

10.5

2.1

8.2

14.3

Real Interest Rate

-0.72

-0.72

-0.72

-0.72

-0.72

Government Debt to GDP

-53.6

-64.8

-0.0

-21.2

-77.1

United States Scenario

Real GDP

3.6

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.5

Consumption

4.0

0.2

0.2

0.4

0.6

Real Interest Rate

-0.13

-0.13

-0.13

-0.13

-0.13

Government Debt to GDP

-43.0

0.0

-0.0

0.0

-0.0

Euro Area Scenario

Real GDP

0.4

5.7

0.4

0.6

0.8

Consumption

0.2

6.5

0.2

0.6

1.4

Real Interest Rate

-0.14

-0.14

-0.14

-0.14

-0.14

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

-47.4

-0.0

0.0

0.0

Emerging Asia Scenario

Real GDP

0.1

0.1

0.1

3.4

0.2

Consumption

0.3

0.3

0.4

2.6

0.4

Real Interest Rate

-0.01

-0.01

-0.01

-0.01

-0.01

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

0.0

0.0

-13.5

-0.0

Other Countries Scenario

Real GDP

1.0

1.3

0.9

2.2

11.7

Consumption

1.6

3.1

1.3

4.1

11.6

Real Interest Rate

-0.25

-0.25

-0.25

-0.25

-0.25

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

0.0

-0.0

0.0

-67.0

39

Table 3. Cooperative Versus Regional Public Pension Reform—Reducing

Spending on Pension Benefits

US

EU

JA

AS

RC

Global Scenario

Real GDP

1.6

1.7

1.7

2.0

1.9

Consumption

1.3

1.7

-0.3

0.8

2.4

Real Interest Rate

-0.82

-0.82

-0.82

-0.82

-0.82

Government Debt to GDP

-53.2

-58.1

-0.0

-21.3

-68.8

United States Scenario

Real GDP

0.5

0.3

0.4

0.4

0.4

Consumption

1.3

-0.2

-0.0

0.1

-0.0

Real Interest Rate

-0.18

-0.18

-0.18

-0.18

-0.18

Government Debt to GDP

-41.0

0.0

-0.0

0.0

0.0

Euro Area Scenario

Real GDP

0.2

0.4

0.3

0.4

0.3

Consumption

-0.1

1.5

-0.0

0.0

-0.0

Real Interest Rate

-0.15

-0.15

-0.15

-0.15

-0.15

Government Debt to GDP

-0.0

-42.5

0.0

0.0

0.0

Emerging Asia Scenario

Real GDP

0.0

0.1

0.1

0.1

0.1

Consumption

-0.0

-0.0

-0.0

0.5

-0.0

Real Interest Rate

-0.03

-0.03

-0.03

-0.03

-0.03

Government Debt to GDP

-0.0

0.0

-0.0

-14.3

0.0

Other Countries Scenario

Real GDP

0.5

0.6

0.6

0.6

0.7

Consumption

-0.2

-0.0

-0.2

-0.1

2.1

Real Interest Rate

-0.29

-0.29

-0.29

-0.29

-0.29

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

-59.8

40

Table 4. Cooperative Versus Regional Public Pension Reform—Raising

Contribution Rates

US

EU

JA

AS

RC

Global Scenario

Real GDP

0.5

0.0

1.2

1.0

0.0

Consumption

0.1

-0.5

-0.6

-0.3

-0.1

Real Interest Rate

-0.62

-0.62

-0.62

-0.62

-0.62

Government Debt to GDP

-45.9

-50.2

-0.0

-19.2

-62.3

United States Scenario

Real GDP

-0.4

0.2

0.3

0.3

0.2

Consumption

0.4

-0.2

-0.1

-0.0

-0.2

Real Interest Rate

-0.14

-0.14

-0.14

-0.14

-0.14

Government Debt to GDP

-37.8

-0.0

-0.0

0.0

-0.0

Euro Area Scenario

Real GDP

0.1

-1.2

0.2

0.2

0.1

Consumption

-0.2

-0.3

-0.1

-0.1

-0.4

Real Interest Rate

-0.11

-0.11

-0.11

-0.11

-0.11

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

-40.4

-0.0

0.0

0.0

Emerging Asia Scenario

Real GDP

0.0

0.0

0.1

-0.1

0.1

Consumption

-0.1

-0.1

-0.0

0.3

0.0

Real Interest Rate

-0.03

-0.03

-0.03

-0.03

-0.03

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

-0.0

-0.0

-14.5

0.0

Other Countries Scenario

Real GDP

0.3

0.3

0.4

0.2

-1.2

Consumption

-0.4

-0.5

-0.4

-0.8

0.1

Real Interest Rate

-0.22

-0.22

-0.22

-0.22

-0.22

Government Debt to GDP

0.0

0.0

-0.0

0.0

-57.0

41

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

The benchmark reform scenarios depend on many assumptions, ranging from agents‘ degree

of impatience and myopia, to the timing of fiscal consolidation. As such, we test the

sensitivity of those benchmark results to changes in selected key parameter values and

investigate the potential shifts in the impact of the public pension reform on the economy.

We focus on the results of the benchmark cooperative global reform scenarios

26

and apply the

tests to the benefit cut scenario except for two tests, the sensitivity of hours worked to a raise

in retirement age and the role of monetary policy accommodation in the short run. To keep

the paper concise, we report the qualitative results of the main tests and refer the reader to

Appendix 2 for a quantitative assessment accompanied by Figures 18 to 24. The sensitivity

tests are the following:

A smaller increase in labor supplied in response to an increase in retirement age

reduces real activity. The benchmark case assumes no change in hours worked and

effort.

A shorter planning horizon with more myopic agents leads to a larger drop in

consumption initially but higher real GDP in the medium run driven by a boost in

investment resulting from an increased labor supply. Under a much longer planning

horizon, agents become far more Ricardian in their behavior. The demand effect is far

weaker with consumption behavior barely changing in response to reform in both the

short and long run. The supply and the capital intensity of production respond a lot

less which in turn reduces the effect of fiscal reform on real interest rates—the latter

does not respond in the long run to the global reform which lowers debt permanently.

Increasing the share of liquidity-constrained agents in the population to 50 percent in

all regions leads to a reduction in consumption in the United States and the euro area

(regions where this share has doubled), contrary to the benchmark results. Over the

medium run, interest rates fall relative to benchmark, boosting investment and the

long run level of real GDP. Emerging Asia and the block of remaining countries

(regions for which this share does not change) benefit from lower world interest rates,

which actually leads to a small improvement in consumption starting in the first year.

As for the timing of fiscal consolidation, having the public pension spending adjust

immediately to its lower long-run level depresses consumption in the short run for

most regions. The difference is larger in the remaining countries block due to a larger

share of

LIQ

households. The increase in government savings crowds out the need

for private savings much quicker, but investment picks up faster, which means that

26

For the most part, individual country reform scenarios (as discussed in Section IV. B.) rely on the parameters

discussed below in a similar fashion.

42

the recovery in real GDP happens much earlier than in the benchmark reform

scenario.

Monetary policy accommodation for one or two years boosts consumption and real

GDP at the expense of added inflation volatility. Short-run demand pressure results in

movements in inflation away from its target and a further decline in real interest rates,

prolonging the initial positive impact of the public pension reforms. Over the short

run, real GDP and consumption rise considerably more relative to the benchmark

scenario, and public finances improve as government deficits decline faster in light of

lower debt service payments. When normal conduct of monetary policy returns, there

is the usual dampening effect in the medium run. In the long run, the economy

follows the same path as in the benchmark scenario.

The formulation of inflation behavior can have an effect on real variables. In the case

where the United States alone carries out public pension reform, there is a short-run

decline in consumption, because of inflationary pressures that lead to an increase in

interest rates by the monetary authority. However, by either cutting the degree of

inflation persistence, or altering how inflation persistence is determined, consumption

will be positive. Such a change to the calibration of the model would be at the

expense of other properties such as the volatility of exchange rates, and the possibility

for effective monetary accommodation.

27

IV. CONCLUSION

We considered reforms to the pension system that can help ensure the long-run viability of

public finances, while mindful of their short-run effect on economic activity in the midst of a

global financial crisis. This is carried out within a dynamic general equilibrium model

(GIMF) that captures the important economic interrelationships at a national and

international level. We emphasized measures to contain and fund the rising costs of age-

related spending in the medium to long run. We find that reforms which lead to short-run

adverse effects on real GDP (i.e., benefit reductions) are largely outweighed by the benefits

of declining real interest rates and the positive effect on future potential productive capacity.

The reform which has the most positive effects in the long run is lengthening the working

lives of employees, effectively raising the size of the active labor force relative to the retiree

population. It helps boost domestic demand in the short run but also eases off the pressure on

governments to cut pension benefits alone—which can lead to additional private savings and

cause fragile domestic demand to fall in the short run—or to raise payroll and labor income

taxes—which can distort incentives to supply labor. We also found that the impact on real

27

The latter property is a linchpin of many results in other work on fiscal stimulus and consolidation with

GIMF, such as Freedman and others (2009a).

43

GDP of a cooperative approach to age-related fiscal reforms is greater compared to a case

where one but not all regions undertake reform.

In terms of public finances, our results generally show that stabilizing the GDP share of age-

related expenditures leads to a sizable decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio. Early efforts and

resolute action to reduce future age-related spending or finance the spending through

additional tax increases and other measures (preferably through an increase in retirement age)